Abstract

The sole aim of this article is to examine the relative contribution of suction/injection parameter on Taylor–Dean flow in a composite annular gap partially filled with porous material. In the present setup, the Newtonian fluid flow is induced by the circumferential motion of both cylinders and pressure gradient imposed in the Azimuthal direction. The mathematical model governing the flow is rendered dimensionless using appropriate dimensionless quantities transformed using the Laplace transform technique. Using suitable Ansatz, the equation is reduced to the Bessel differential equations and solved. The solution of converted to the time domain using a well-known numerical scheme known as the Riemann-sum approximation. The variation of the Newtonian fluid for different flow parameters is presented graphically. The solution method is validated by obtaining the steady-state solution and also using the implicit finite different approach (IFD); comparison of the methods is depicted in tabular form (see Tables 1, 2). It is deduced generally that the Newtonian fluid is higher when injection at the outer cylinder except when Da is small also higher interfacial velocity can be achieved by taking positive value of \(\beta\).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Several years back, the practical and theoretical steady of steady and time-dependent state of circumferential flow of Newtonian fluid in an annular duct has been of major interest to different researchers. This can be attributed to its relevance in various fields of endeavors such as biofluid mechanics, Bio-medical, mechanical, and Hemodynamics engineering. The first and pioneering work in Laminar flow in annulus due to azimuthal pressure gradient was presented by Dean [1]. This laudable and inspiring work has drawn many other researchers toward studying circumferential flow in different geometries. These include the work of Gupta and Gupta [2]. Tsangaris [3], Goldstein [4], Bhatnagar [5], Uchida [6], Rechardson [7], and Dryden and Murnaghan [8]. Gupta et al. [9] theoretically examined the analytical solution responsible for pulsatile viscous flow induced by a harmonically oscillating pressure gradient in a straight elliptic annular gap with application to the motion of the cerebrospinal fluid in the human spinal cavity.

Tsangaris et al. [10] presented laminar fully developed flow in an annular gap subject to an imposed oscillating Azimuthal pressure gradient. In a similar work, Tsangaris and Vlachakis [11] carried out an analytical solution of the Navier–Stokes equations for the fully developed laminar flow in a cylindrical annular duct. Tending the frequency of the oscillating pressure gradient to zero, the work of Goldstein is obtained as a limiting case.

Relating to the present investigation, several theoretical and experimental work using different numerical technique and analytical study has been carried out to have a better understanding of this phenomenon.

Jha and Yahaya [12] examined laminar and fully developed time-dependent flow formation in the region between two horizontally stationary impermeable concentric cylinders with an applied circumferential pressure gradient in the annulus. It is revealed that as time passes, the velocity increases till it attains a steady-state. Jha and Yahaya [13] later extended the work to the case when the walls of the cylinders are permeable. They reported that in addition to the results obtained from their previous work (see Jha and Yahaya [12]), the velocity profile is inversely proportional to the suction/injection parameter.

In the recent past, in an attempt to have an insight into the influence of unsteady pressure gradient on different flow formations, Yen and Chang [14] embarked on an investigation of the role of time-dependent pressure gradient on magnetohydrodynamic flow in a bounded channel; in their work, three cases of unsteady pressure gradient were considered; these are given as follows: pulse, step, and periodic pressure gradient. In another work, Nandi [15] examined time-dependent flow of a viscous incompressible and electrically conducting fluid within a porous annulus subject to an external radial magnetic field with an exponentially decreasing/increasing time-dependent pressure gradient. A theoretical and analytical solution of Newtonian and Non-Newtonian fluid flows in cylindrical and annular pipes due to an arbitrary time-dependent pressure gradient and arbitrary steady initial flow was investigated by McGinty et al. [16]. Similarly, Mendiburu et al. [17] utilized both Fourier series and integral transforms in theoretical examination of unsteady flow in a channel with constant and variable pressure gradient. As time increases, a constant pressure gradient is gradually achieved.

To have a better insight into the circumferential fluid flow within two cylinders, several semi-analytical works have been carried out using the Riemann-sum approximation (RSA) approach. Using this method, Jha and Gambo [18] presented an investigation of “the impact of suction/injection and an exponentially decaying/growing time-dependent pressure gradient on unsteady Dean flow through an annulus.” It is revealed that the skin frictions on both walls can be minimized by imposing an exponentially decaying pressure gradient on the flow. Using the same approach, Jha and Gambo [19] studied the impact of an exponentially decaying/growing time-dependent pressure gradient on unsteady Dean flow in an annulus. The findings revealed that maximum velocity occurs when the time-dependent pressure gradient is growing exponentially other related research works using this approach include the work of Jha and Yusuf [20]. Other relevant works include the work of Azad and Andallah [21], Sayed-Ahmed et al. [22], Tsimpoukis, Valougeorgis [23], Khali et al. [24], and Waters and Pedley [25].

The uniqueness of this work is to investigate the influence of wall porosity on unsteady Taylor–Dean flow in an annulus partly filled with porous material. It is hoped that this research work will help in understanding the procedure to better minimize wall frictional force for free flow formation. Solution of the velocity field and skin friction at both walls has been obtained using the combination Laplace transform and RSA approach. The IFD method has also been used to solve governing model while the steady-state solution has been derived equally. The effect of the various entering flow parameters on the flow formation is studied with the help of line graphs and numerical tables.

Methods

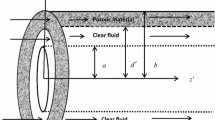

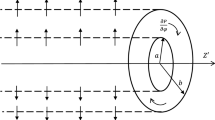

The time dependent, fully developed, and incompressible circumferential flow between two infinite co-axial horizontal porous “cylinders containing fluid and porous layer separated by a permeable thin interface with fluid occupying the interval \(d^{^{\prime}} \le r^{\prime } \le r_{0}\) while the interval \(r_{{{\text{in}}}} \le r^{\prime } \le d^{^{\prime}}\) is occupied by a fluid-saturated porous material of uniform permeability. rin and r0 are the radii of the inner and the outer cylinder, respectively, as shown in Fig. 1. The fluid is set in motion due to sudden application of constant circumferential pressure gradient and the angular, rotating with an angular velocity \(\omega_{{{\text{in}}}}\) and \(\omega_{0}\).” The velocity of the fluid is showed to be a function of the radial coordinate \(r^{\prime }\) and time t only. The flow in the porous region is governed by the Darcy law while the flow in the clear region is governed by the usual Navier–Stokes equations. Continuity of velocity and shear stress has been used at the fluid–porous interface. In cylindrical coordinates, these equations are given as

The initial and the condition at the surfaces for the problem under consideration are

With the dimensional matching condition at the interface given as

Using the following non-dimensional quantities:

Using the following dimensionless parameters defined in Eq. (5) on Eqs. (1) to (4)

Subject to the following dimensionless initial and boundary conditions

With the matching condition at the interface given as

The Laplace domain of Eqs. (6) to (9) can be obtained using the Laplace transform technique \(\overline{U}_{{\text{p}}} \left( {R,\vartheta } \right) = \int_{0}^{\infty } {U_{{\text{p}}} \left( {R,t} \right)e^{ - \vartheta t} {\text{d}}t} \;\;{\text{and}}\;\; \overline{U}_{{\text{f}}} \left( {R,\vartheta } \right) = \int_{0}^{\infty } {U_{{\text{f}}} \left( {R,t} \right)e^{ - \vartheta t} {\text{d}}t}\) (where \(\vartheta > 0\) is the Laplace parameter) subject to initial condition gives:

Subject to the following boundary condition

With the matching condition at the interface given as

Equations (10) and (11) can be transform to Bessel function using the following equations;

Letting \(\gamma = 1\) and then applying Eq. (14) on Eqs. (10) and (11), the solutions in terms of the modified Bessel function obtained are given as:

where \(\eta = \sqrt {\left( {\frac{1}{Da} + \vartheta } \right)} , n = \left( {\frac{S}{2} + 1} \right)\) and In, Kn are the modified Bessel function of a first and second kind, respectively, of order n.

using Eq. (12) and on Eqs. (15) and (16) the constants \(C_{5} ,{ }C_{6} ,{ }C_{7} ,{ }C_{8} { }\) and Ui are obtained as

Skin friction

To evaluate the skin friction on both the inner and the outer cylinder in the Laplace domain, we use \(\left. {R\frac{\partial }{\partial R}\left( {\frac{{\overline{U}_{{\text{p}}} }}{R}} \right)} \right|_{R = 1}\) and \(- \left. {R\frac{\partial }{\partial R}\left( {\frac{{\overline{U}_{{\text{f}}} }}{R}} \right)} \right|_{R = \lambda },\) respectively. On simplification, we have

Before analyzing the solution above, Eqs. 15–18 need to be inverted to the time domain. However, a deep literature study in the cause of this research revealed that there is no simple analytical way to obtain the Laplace inverse of Eqs. 15–18 Hence, we follow the numerical approach used in the work of Khadrawi and Al-Nimr [26], Jha and Apere [27], and several other researchers too numerous to mention. This technique is based on the RSA. According to this method, any function in the Laplace domain can be inverted to the time domain as shown below.

In the equation above, \(i = \sqrt { - 1}\) while Re denotes “the real part of the term with a summation. N denotes the number of terms used in the RSA and \(\varepsilon\) represents the real part of the Bromwich contour used in inverting Laplace transforms. This procedure involves a single summation for the numerical process and its accuracy largely depends on the value of \(\varepsilon\) and N. According to the work of Tzou [28], the value of \(\varepsilon t\) that best satisfies the result is 4.7

Validation of the method

The exact solution of the steady-state velocity is obtained and used to validate the RSA approach used in this work. It is revealed that at large time, the transient state solution coincides with the steady-state velocity. This is obtained by letting \(\frac{\partial ()}{{\partial t}} = 0\) in Eqs. (1) and (4) to obtain the following differential equations

Subject to the following boundary condition

With the matching condition at the interface denoted by d given as

Equation (20) is solved by applying the transformation giving by

Putting \(\gamma = P = 1\) and applying Eq. (24) on Eq. (20), the solution in terms of modified Bessel function is given as:

Equation (21) is solved by letting \(R = e^{\varphi }\) and simplifying, the resulting second-order ODE is given by

Applying the usual method of undetermined coefficient yield

Using Eqs. (22) and (23) on Eqs. (25) and (27), the constants \(D_{5} ,{ }D_{6} ,{ }D_{7} ,{ }D_{8} { }\) and \(U_{{{\text{is}}}}\) are obtained as.

\(D_{5} = - h3 ui + h2, D_{6} = h5 ui - h4, D7 = - h8 ui - h7, D8 = h10 ui + h9\), \(Ui = \frac{h16}{{h17}}\) the constant \(h_{1} , h_{2} , h_{3} , \ldots ,h_{17}\) in the above equations are

The accuracy of the RSA is further established using the IFD approach on Eqs. (6) to (9). The values generated using these two approaches are presented in the tables below for numerical comparison. This numerical scheme in comparison with the values obtained from the RSA approach at a large time as well as the closed-form solution of the steady-state velocity gives an excellent agreement. It is worthy to note that the numerical values obtained using the IFD method at transient state also agree significantly with the ones obtained using the RSA approach for a small value of time (see Tables 1, 2).

Results and discussion

To have a clear insight into the effect of various parameters controlling the unified solution of the model governing the flow formation, a MATLAB code is written to compute and generate the line graphs and to obtain its numerical values for some selected entering parameters. These parameters include the Darcy number (Da), time (t), viscosity ratio \(\left( \gamma \right)\), interfacial radial distance (d), adjustable coefficient of the stress jump condition \(\left( \beta \right)\), the radii ratio \(\left( \lambda \right)\), and the suction/injection parameter. The effect of the above parameters on fluid velocity, interfacial velocity, and skin friction on both surfaces presented in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 is discussed below.

Figures 2, 3 and 4 reveal the variation in velocity profiles t, Da, and \(\beta,\) respectively. Figure 2 shows that fluid velocity is an increasing function of time until steady-state is attained, with injection at either the outer cylinder or the inner cylinder. However, it is observed that velocity is higher near the inner cylinder when fluid injection is at the inner cylinder for small value of Da. Figures 3 and 4 show that at transient state, fluid velocity profiles increase with increase in Da and \(\beta\) for both suction and injection on both cylinders. Velocity is generally higher when fluid injection is at the outer cylinder.

Change in transient state interfacial velocity (ui) with t, d and \(\beta\) is presented in Figs. 5 and 6. It is established in both figures that ui increases with t. To achieve higher interfacial velocity, large values of \(\beta > 0\) are required (see Fig. 5); this fit can also be achieved by decreasing the region partially occupied by the porous material. The reverse occurs when the region filled with clear fluid is decreased (see Fig. 6).

Figures 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 showcase the effect of various parameters on skin friction at the outer and at the inner cylinder. It is generally observed that skin friction increases with an increase in time. Variation in skin friction at the inner cylinder for different values of s and t is shown in Fig. 7. It is important to note that shear stress is relatively lower at the inner cylinder when injection is on the outer cylinder. A similar observation is depicted in Fig. 8 as skin friction is found to be lower at the outer cylinder when injection is on the inner cylinder. The reverse situation is presented if high higher shear is desired.

The relative contribution of the azimuthal pressure gradient is illustrated in Figs. 9 and 10 and both figures show an increase in skin friction with pressure; a significant increase in the shear stress is also observed at the inner cylinder. It is interesting to note that the direction of suction/injection flow has less impact on the skin friction at the outer cylinder for pressure gradient (P > 8).

Figures 11 and 12 reveal the variation of skin friction at the inner cylinder and the outer cylinder, respectively, for different values of S and d. Figure 11 shows that shear stress at the inner cylinder increases with a decrease in the region occupied by clear fluid while an increase in the region occupied by clear fluid leads to a decrease in shear stress at the outer cylinder (see Fig. 12).

Conclusion

This paper presents the contribution of angular rotation of both cylinders on transient azimuthal pressure-driven flow partially filled with porous materials. The impact of various flow parameters on the fluid velocity, interfacial velocity, and shear stress on both cylinders is presented. The accuracy of the numerical schemes used is shown with the aid of Table. Based on the figures and the numerical values generated, the following conclusions are drawn:

-

1.

Velocity is higher near the inner cylinder when fluid injection is at the inner cylinder for small value of Da.

-

2.

Velocity is generally higher when injection is at the outer cylinder.

-

3.

To achieve higher interfacial velocity, large values of \(\beta > 0\) are required.

-

4.

It is interesting to note that the direction of suction/injection flow has less impact on the skin friction at the outer cylinder for pressure gradient (P > 8).

-

5.

Shear stress at the inner cylinder increases with a decrease in the region occupied by clear fluid.

-

6.

It is important to note that shear stress is relatively lower at the inner cylinder when injection is on the outer cylinder.

-

7.

An interesting observation in this research is that wall porosity reduces the time taken to reach steady state.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable to this article.

Abbreviations

- d :

-

Non-dimensional interfacial radial distance

- d′:

-

Dimensional interfacial radial distance

- Da:

-

Darcy number

- I 1 :

-

First-order modified Bessel function of the first kind

- I 2 :

-

Second-order modified Bessel function of the first kind

- k′:

-

Permeability of the porous medium

- K 1 :

-

First-order modified Bessel function of the second kind

- K 2 :

-

Second-order modified Bessel function of the second kind

- a :

-

Radius of inner cylinder

- b :

-

Radius of outer cylinder

- r′:

-

Dimensional radial coordinate

- R :

-

Non-dimensional radial coordinate

- t :

-

Time in non-dimensional form

- t′:

-

Time in dimensional form

- U :

-

Non-dimensional velocity

- u′:

-

Dimensional velocity

- U o :

-

Reference velocity

- u 1 :

-

Dimensional suction/injection

- β :

-

Adjustable coefficient in the stress jump condition

- γ :

-

Ratio of viscosity

- λ :

-

Radii ratio

- ν eff :

-

Effective kinematic viscosity of the porous medium

- ν :

-

Kinematic viscosity of the fluid

- ρ :

-

Density

- p* :

-

Dimensional pressure

- P :

-

Dimensionless pressure

- f:

-

Fluid region

- i:

-

Interface between clear fluid and porous region

- o:

-

Outer surface

- in:

-

Inner surface

- p:

-

Porous region

References

Dean, W.R.: Fluid motion in a curved channel. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 121, 402–420 (1928)

Gupta, R.K., Gupta, K.: Steady flow of an elasticoviscous fluid in porous coaxial circular cylinder. Indian J. Pure Appl. Math. 27(4), 423–434 (1996)

Tsangaris, S.: Oscillatory flow of an incompressible viscous-fluid in a straight annular pipe. J. Mech. Theor. Appl. 3(3), 467 (1984)

Goldstein, S.: Modern Developments in Fluid Dynamics, pp. 315–316. Clarendon Press (1938)

Bhatnagar, R.K.: Flow of an oldroyd fluid in a circular pipe with time-dependent pressure gradient. Appl. Sci. Res. 30(4), 241–267 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00386693

Uchida, S.: The pulsating viscous flow superposed on the steady laminar motion of incompressible fluid in a circular pipe. J. Appl. Math. 7, 403–422 (1956)

Richardson, E.G., Tyler, E.: The transverse velocity gradient near the mouths of pipes in which an alternating or continuous flow of air is established. Proc. Phys. Soc. 42(1), 1–15 (1929)

Dryden, H.L., Murnaghan, F.D., Bateman, H.: Hydrodynamics. Dover Publ. Inc. (1956)

Gupta, S., Poulikakos, D., Kurtcuoglu, V.: Analytical solution for pulsatile viscous flow in a straight elliptic annulus and application to the motion of the cerebrospinal fluid. Phys. Fluids 20(9), 1–12 (2008)

Tsangaris, S., Kondaxakis, D., Vlachakis, N.W.: Exact solution of the Navier–Stokes equations for the pulsating dean flow in a channel with porous walls. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 44(20), 1498–1509 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijengsci.2006.08.010

Tsangaris, S., Vlachakis, N.W.: Exact solution for the pulsating finite gap dean flow. Appl. Math. Model. 31(9), 1899–1906 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2006.06.011

Jha, B.K., Yahaya, J.D.: Transient Dean flow in an annulus: a semi-analytical approach. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 13(1), 169–176 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/16583655.2018.1549529

Jha, B.K., Yahaya, J.D.: Transient Dean flow in a channel with suction/injection: a semi-analytical approach. J. Process Mech. Eng. 233(5), 1–9 (2019)

Yen, J.T., Chang, C.C.: Magnetohydrodynamic channel flow under time-dependent pressure gradient. Phys. Fluids. 4(11), 1355–1360 (1961). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1706224

Nandi, S.: Unsteady hydromagnetic flow in a porous annulus with time-dependent pressure gradient. Pure. Appl. Geophys. 79, 33–40 (1970)

McGinty, S., McKee, S., McDermott, R.: Analytic solutions of Newtonian and non-Newtonian pipe flows subject to a general time-dependent pressure gradient. J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 162, 54–77 (2009)

Mendiburu, A.A., Carrocci, L.R., Carvalho, J.A.: Analytical solutions for transient one-dimensional Couette flow considering constant and time-dependent pressure gradients. Engenharia Térmica (Therm. Eng.). 8, 92–98 (2009)

Jha, B.K., Gambo, D.: Combined effects of suction/injection and exponentially decaying/growing time-dependent pressure gradient on unsteady Dean flow: a semi-analytical approach. Int. J. Geomath. 11, 28 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13137-020-00164-w

Jha, B.K., Gambo, D.: Role of exponentially decaying/growing time-dependent pressure gradient on unsteady Dean flow: a Riemann-sum approximation approach. Arab. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 28(1), 1–10 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/25765299.2020.1861754

Jha, B.K., Yusuf, T.S.: Transient pressure-driven flow in an annulus partially filled with porous material: Azimuthal pressure gradient. Math. Model. Eng. Probl. 5(3), 260–267 (2018)

Azad, M.A.K., Andallah, L.S.: Explicit exponential finite difference scheme for 1D Navier–Stokes equation with time-dependent pressure gradient. J. Bangladesh Math. Soc. 36, 79–90 (2016)

Sayed-Ahmed, M.E., Attia, H.A., Ewis, K.M.: Time-dependent pressure gradient effect on unsteady MHD Couette flow and heat transfer of a Casson fluid. Engineering 3, 38–49 (2010)

Tsimpoukis, A., Valougeorgis, D.: Rarefied isothermal gas flow in a long circular tube due to oscillating pressure gradient. Microfluidics Nanofluidics 22(1), 5 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10404-017-2024-2

Khali, S., Nebbali, R., Bouhadef, K.: Effect of a porous layer on Newtonian and power-law fluids flow between rotating cylinders using lattice Boltzmann method. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40430-017-0809-6

Waters, S.L., Pedley, T.J.: Oscillatory flow in a tube of time-dependent curvature. Part 1. Perturbation to flow in a stationary curved tube. J. Fluid Mech. 383, 327–352 (1999)

Khadrawi, A.F., Al-Nimr, M.A.: Unsteady natural convection fluid flow in a vertical microchannel under the effect of the Dual-Phase-Lag heat conduction model. Int. J. Thermophys. 28, 1387–1400 (2007)

Jha, B.K., Apere, C.A.: Unsteady MHD two-phase Couette flow of fluid-particle suspension in an annulus. AIP Adv. 1, 042121-1-042121–15 (2011)

Tzou, D.Y.: Macro to Micro Scale Heat Transfer: The Lagging Behavior. Taylor and Francis (1997)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

No funding was received in the course of this research work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BKJ modeled the mathematical equations, solved the models, and supervised the research work while TSY was responsible for the generation and interpretation of the graphs, both authors have read and approved the publication of this article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jha, B.K., Yusuf, T.S. Transient Taylor–Dean flow in a composite annulus with porous walls partially filled with porous material. J Egypt Math Soc 30, 2 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42787-022-00136-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42787-022-00136-z