Abstract

Background

Traits of mature trees, such as bark thickness and texture, have been documented to promote resistance or resilience to heating in fire-prone forests. These traits often assist managers as they plan and promote prescribed fire management to accomplish specific land management objectives. Species are often grouped together as pyrophobes or pyrophytes as a result of these features. Nonetheless, little is known about species-specific traits of other structures, such as bud diameter, length, mass, moisture content, and surface area, that might be related to heat tolerance. Many prescribed fires are utilized in the eastern United States to control regeneration of less desired species, which could apply a more mechanistic understanding of energy doses that result in topkilling mid-story stems. In this study, we investigated potential relationships between terminal bud mortality from lateral branches of midstory stems and species-specific bud features of six eastern US deciduous trees. Characterized at maturity as either pyrophytes or pyrophobes, each was exposed to different heat dosages in a laboratory setting.

Results

Bud diameter, length, mass, moisture content, and surface area differed by species. Bud percent mortality at the first heat flux density (0.255–0.891MJm−2) was highest for two pyrophobes, chestnut oak (Quercus montana Willd.) and scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea Münchh). For the second heat flux density (1.275–1.485MJm−2), bud percent mortality was highest for these species and red maple (Acer rubrum L.). Principal component analysis suggested that bud surface area and length differentiated species. Red maple, chestnut oak, and scarlet oak produced clusters of buds, which may explain their more pronounced bud mortality. Yellow-poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera L.) was also present in that cluster, suggesting that its unique bud architecture of pre-emergent leaves may have elicited responses most similar to those of the clustered buds.

Conclusions

Contrary to expectations, lateral buds of species regarded as pyrophytes at maturity displayed some of the highest values of bud percent mortality when heated at two heat flux densities generated in a laboratory. Their responses may be related to clustering of their lateral buds. Testing of additional species using these methods in a laboratory setting, and perhaps additional methodologies in the field, is warranted.

Resumen

Antecedentes

Las características de árboles maduros, como el espesor de la corteza y su textura, han sido documentadas como promotoras de la resistencia o resiliencia al calor en boques proclives a los incendios. Estas características frecuentemente ayudan a los gestores a planear y promover las quemas prescriptas como herramienta para lograr objetivos específicos de manejo de tierras. Algunas especies son frecuentemente agrupadas como pirófobas o pirófitas como resultado de esas características. Sin embargo, se conoce muy poco sobre las características especie-específicas de pequeños tallos como el diámetro, largo, masa, contenido de humedad y superficie de los brotes, que pueden relacionarse con la tolerancia al calor. Muchas quemas prescriptas son utilizadas en el este de los EEUU para controlar la regeneración de las especies menos deseadas, que podrían ayudar a un mejor entendimiento mecanístico de las dosis de energía que resulten en la muerte apical de pequeños tallos a alturas intermedias. En este estudio, investigamos las relaciones potenciales entre la mortalidad de brotes laterales y las características especie-específicas de brotes de seis especies de árboles deciduos del este de los EEUU. Caracterizadas a su madurez tanto como pirrófitas o como pirófobas, cada una fue expuesta a diferentes dosis de calor en experimentos de laboratorio.

Resultados

El diámetro, largo, masa, contenido de humedad y superficie de los brotes difirieron entre las especies. El porcentaje de mortalidad de los brotes durante al primer flujo de densidad de calor (0.255 MJm-2 – 0.891MJm-2) fue máxima para dos especies de pirófobas, el roble castaño (Quercus montana) y roble escarlata (Quercuor coccinea). Para el segundo flujo de densidad de calor (1.275MJm-2 - 1.485MJm-2), el porcentaje de mortalidad de los brotes fue mayor para esas dos especies y para el arce rojo (Acer rubrum). El análisis de componentes principales sugirió que la superficie del brote y su largo diferenciaron a las especies, y el arce rojo, el roble castaño y el roble escarlata producen brotes en racimos que pueden explicar la mayor mortalidad de estos brotes. El álamo amarillo estuvo también presente en ese grupo, lo que sugiere que la particular arquitectura de sus brotes de hojas pre emergentes puede haber suscitado respuestas muy similares a aquellos de brotes arracimados.

Conclusiones

Contrariamente a lo esperado, los brotes laterales de las especies clasificadas como pirófitas en su madurez, mostraron algunos de los valores más altos de porcentajes de muerte de los brotes cuando fueron sometidas a los flujos de densidad de calor generados en el laboratorio. Estas respuestas pueden estar relacionadas con el arracimado de sus brotes laterales. Se sugiere la prueba de especies adicionales mediante el uso de este método en el laboratorio, y quizás de metodologías adicionales a campo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is well-documented that vegetation exhibits species-specific, fire-adapted traits (Hammond et al. 2015; Keeley et al. 2011; Violle et al. 2007). These include, but are not limited to, bark thickness and texture (Kidd and Varner 2019; Pausas 2015; Eberhardt 2013), leaf physical properties and chemistry (Coates et al. 2020; Belcher 2016; Varner et al. 2015), and mycorrhizal associations (Dove and Hart 2017; Boerner et al. 2008). Traits such as rhizomes or belowground buds allow trees that are topkilled (only aboveground growth is killed, not belowground resources) to resprout after a fire and quickly reoccupy a given space on the landscape (Agee 1993). Species possessing traits that tend to withstand and propagate fire are often labeled pyrophytes, while pyrophobes generally describe species that possess opposing traits (Kane et al. 2008, Blackhall et al. 2017).

Globally, prescribed fire practitioners rely on species-specific traits to achieve specific management objectives of prescribed burns. Specifically, in the southeastern US, a region where prescribed fire is used to manage approximately 4.5 million ha annually (Melvin 2018), these traits are used to target individual burn objectives and understand mechanisms driving fire effects, such as seasonal differences in plant response to fire (Hiers et al. 2000; Ruswick et al. 2021), litter driven variation in energy release (Hiers et al. 2009; Loudermilk et al. 2014), or litter decomposition influence on post-burn fire effects (Arthur et al. 2012; Carpenter et al. 2021).

Location, position, and traits of buds for surviving heat from fire are critically important when considering potential desired fire effects. While tree bark thickness (Varner et al. 2016), litter characteristics (Kane et al., 2008), and seeds (Wiggers et al. 2017) have been researched for numerous pyrophytes, tree buds have received less attention for their ability to survive fire. Clarke et al. (2012) investigated resprouting as a primary functional trait in response to fire-induced injury and suggested that bud position is often ignored when vegetative resprouting potential is described and defined for a given species. Basal and aerial buds (terminal buds on lateral branches) may differ in terms of their heat tolerance and other physical traits that would confer advantages in replacing aboveground tissues, besides the critical advantage of resprouting (Brose and Waldrop 2006). These authors and others (Balfour and Midgley 2006; Bond 2008; Burrows et al. 2008; Higgins et al. 2000) suggested that resprouting stems are generally fire-resilient because their rapid height growth allows them to be taller than expected flame lengths, protecting the stems from potential crown scorch.

Fire was largely excluded from most of the US during the twentieth century (Lafon et al. 2017; Nowacki and Abrams 2008; Van Lear et al. 2005). Subsequently, changes in species dominance and flammability have occurred, increasing vegetative competition in many locations where prescribed fires are now applied for ecosystem restoration purposes (Alexander and Arthur 2014; Kreye et al. 2018; Nowacki and Abrams 2008). Determining if aerial bud characteristics, such as length and mass, may be related to pre-existing fire tolerance designations could be useful for prescribed fire managers when targeting specific burn parameters to maximize vegetative control of less desired understory and mid-story trees, particularly in deciduous forests where burning is concentrated in months following leaf fall (Knapp et al. 2009; Van der Yacht et al. 2017). Additionally, understanding if and how potential morphological traits influence aerial bud resilience to potential crown scorch of desired species may help fire practitioners optimize burn objectives, parameters, and plans.

To investigate the potential heat tolerance of terminal buds on lateral branches of mid-story trees, a laboratory experiment was conducted using a propane gas tube burner. Six common southeastern US tree species (three pyrophytic and three pyrophobic) were selected for investigation. Six heat “doses” (sensu Smith et al. 2016), differing in height above the propane burner (30 and 60 cm) and heat exposure time (15, 45, and 75 s), were used to heat terminal buds from lateral branches to evaluate bud percent mortality from non-flame energy doses. The study hypotheses were:

-

1.

Bud mortality will differ between species and pyrophytes will exhibit lower percent bud mortality than pyrophobes.

-

2.

Bud mortality will increase as heat dosage increases, regardless of species.

Methods

Study site

The Fishburn Forest, located near Blacksburg, Virginia, in the Ridge and Valley physiographic province (37.188396° N, 80.477018° W), is the property of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Fig. 1). The mean annual temperature range is −6°C (Winter) to 27°C (Summer) and mean precipitation is 103.8 cm (U.S. Climate Data, 2021). Soils are dominated by the Berks (Typic Dystrudepts)-Weikert (Lithic Systrudepts) soil series association. These soils are typically very shallow, well-drained silt loams, being mostly derived from shale, siltstone, and sandstone residuum (Vinson et al. 2017). Many stands within this forest are currently 100–120 years old (Copenheaver et al. 2006).

Location of the Fishburn Forest near Blacksburg, Virginia (Montgomery County), USA (Vinson et al. 2017)

Species selection

Six total species were selected for this study based upon their designations as pyrophytes or pyrophobes (USDA FEIS 2020): pyrophytes included chestnut oak (Quercus montana Willd.), scarlet oak (Quercus coccinea Münchh.), and mockernut hickory (Carya tomentosa Lam.); pyrophobes included red maple (Acer rubrum L.), yellow-poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera L.), and American beech (Fagus grandifolia Ehrh.). Bud physical features, such as bud length, mass, and clustering, appeared to differ for these species and these potential differences provided additional justification for the selection of these specific species (Fig. 2).

Stem selection and bud storage

Fifteen mid-story stems of each species (approximately 5–10 m tall) were identified within the Fishburn Forest. All stems were located on south- to southwest-facing slopes in areas that had not been disturbed in at least the last 10–15 years. Lateral branches were randomly harvested from each mid-story stem on November 16, 2020, immediately following leaf abscission. After harvesting, each branch was gently wrapped in damp paper towels, placed into a plastic bag, and taken back to the laboratory for the evening. A mixture of branches were batched by species from these trees and then used to clip terminal buds the next morning.

Bud heating

To conduct the heat dosage experiment, 648 terminal buds were clipped from the lateral branches on November 17, 2020 (108 buds per species). Thirty additional terminal buds per species were not heated and were used as controls for this experiment. Similar electrical conductivity measurements (see the “Electrolyte leakage and bud percent mortality” section) were recorded for these buds and control bud percent mortality (see the “Electrolyte leakage and bud percent mortality” section) was calculated.

Prior to heating, individual bud mass (to the nearest 0.000 g), length, and diameter (to the nearest 0.00 mm) were measured. Bud surface area (mm2) was calculated using the standard equation for the surface area of a cone.

A 30.5 cm × 45.7 cm heating frame was assembled containing 0.3-mm aluminum wire mesh (model 10105Z; Saint-Gobain North America, Malvern, PA, USA) (Fig. 3A). Along this heating frame, three buds of each species were randomly placed within six 15.24 cm2 squares. With the buds in place, this frame was then fixed upon a 55.9 cm × 76.2 cm × 76.2 cm wooden, adjustable rack at one of two heights above a propane gas tube burner (Tejas Smokers, Houston, TX, USA, model PBM125-44; 3.2 cm inner diameter, 3.8 cm outer diameter, 55.9 cm length): 30 cm and 60 cm (Fig. 3B). Three times were used for bud heat exposure: 15, 45, and 75 s, with heat doses generally following Wiggers et al. (2017). The mass of propane gas used per experimental burn (0.32 g s−1) was measured using a large scale. In Joules, J, this equated to 0.2413, 0.7240, and 1.2060 MJ for the 15, 45, and 75 s treatments, respectively. To estimate the heat flux density at the treatment heights, we calculated the amount of heat required to raise a 5 mm tungsten bead to equilibrium temperature: Q = cm∆T where c = the specific heat capacity of tungsten (0.134 Jg−1K−1), m = the bead mass (0.650 g), and ∆T = the change in temperature in K from ambient to steady state at each height. The bead size was chosen to approximate the middle size range of the buds and to be able to approximate the heat dose over the different treatment heights and exposure times. The heat flux density at 30 cm was 19.8 kWm−2 and at 60 cm was 17.0 kWm−2. By this method, the 60-cm doses at 15, 45, and 75 s were 0.255 MJm−2, 0.755 MJm−2, and 1.275 MJm−2; for 30 cm: 0.297 kJm−2, 0.891 kJm−2, and 1.485 MJm−2. Using this experimental design, 18 buds per species were heated at each height and exposure combination.

Electrolyte leakage and bud percent mortality

Immediately after heat exposure, mass was again obtained for each bud to determine the bud water content prior to heating. Each bud was then placed in 25-mL deionized water in 25 mm × 140 mm (40 mL) test tubes (Ilik et al. 2018; Peixoto and Sage 2016). Twenty-four hours after heating, electrical conductivity (EC) of the deionized water was measured using an Apera 700 Series Benchtop pH/Conductivity Meter (Apera Instruments, Inc., Columbus, OH, USA). After these measurements were taken, each bud was then removed from the test tube, placed on a ceramic plate, and heated for 1 min using a 1100W microwave. After microwaving was completed, buds were placed back in their test tubes. Twenty-four hours post-microwave, EC was re-measured. Bud percent mortality (BPM) for each heated bud was then calculated as:

Statistical analyses

Bud mass, length, diameter, surface area, water content, and BPM values were entered into JMP 15 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Data were not normally distributed, therefore ranks were assigned to each value to perform an analysis of variance (ANOVA) for each variable using a Wilcoxon (1 or 2 groups) or Kruskal-Wallis test (more than 2 groups) (Conover 1971).

Exploratory preliminary analyses were conducted to determine if heat flux density was impacted by differences in height above the propane burner and exposure time. Mean BPM did not differ at 30 and 60 cm above the propane burner (p = 0.6761). Mean BPM was significantly greater at 75 s than at 15 or 45 s (p = 0.0013). Therefore, only one height above the propane burner and two exposure times were used for mean BPM comparisons between the heated buds and the untreated, control buds, yielding two heat flux density ranges for comparison: 0.255–0.891 MJm−2 and 1.275–1.485MJm−2. This treatment designation yielded 54 heated buds per heat flux density.

Additional ANOVA were conducted for (1) individual species and (2) tree species functional groups (pyrophyte vs. pyrophobe). The models constructed to test these parameters were:

-

A.

Species-specific model

$$\textrm{Mean}\ \textrm{BPM}=\textrm{species}+\textrm{heat}\ \textrm{flux}\ \textrm{density}+\textrm{species}\times \textrm{heat}\ \textrm{flux}\ \textrm{density}$$ -

B.

Functional group model

$$\textrm{Mean}\ \textrm{BPM}=\textrm{tree}\ \textrm{species}\ \textrm{functional}\ \textrm{group}+\textrm{heat}\ \textrm{flux}\ \textrm{density}+\textrm{tree}\ \textrm{species}\ \textrm{functional}\ \textrm{group}\times \textrm{heat}\ \textrm{flux}\ \textrm{density}$$

If differences were detected between the interaction terms, a Steel-Dwass test was conducted to determine specific differences between the parameters and their levels. Differences were declared statistically significant at α = 0.05.

Principal component analysis

To determine potential correlations between bud physical traits and BPM between species, principal component analysis was conducted (Jolliffe 2005). Bud mass, length, diameter, surface area, and water content were entered in JMP as “independent variables.” Heat exposure time and species were entered as “supplementary variables.” Combinations of the independent variables were evaluated to determine the highest combined component percentage (sum of the percentages explained by each axis), then data from Components 1 and 2 were saved from the analysis that produced the highest combined component percentage. Linear regressions were then utilized to determine the highest r2 value for the estimation of the component data using the independent variables. The formatting loading matrix was additionally evaluated to confirm the relationships between the independent variables and the saved component data.

Results

Bud physical features

Bud mass was greatest for mockernut hickory (p < 0.0001) (Table 1) and was over 3 times greater than buds from the next largest species, yellow-poplar. Bud length was greatest for American beech, followed by mockernut hickory (p < 0.0001) (Table 1). Yellow-poplar and chestnut oak did not differ from one another and were followed by scarlet oak and red maple in descending order, each statistically different in bud length. Mockernut hickory had the greatest bud diameter (p < 0.0001) (Table 1), which was at least 38% greater than all other species. Bud surface area was also greatest for mockernut hickory (p < 0.0001) (Table 1), with no other species accounting for at least 50% of its value. Bud moisture content was greatest for red maple at 36.96% and this differed from all other species except American beech (p < 0.0001) (Table 1).

Species-specific bud percent mortality model

For the species-specific model, the main effect of species, heat flux density, and their interaction was significant (all p < 0.05). Bud percent mortality values produced a cluster of species, including chestnut oak, southern red oak, and red maple, with the greatest mortality. This was followed by American beech, yellow-poplar, and mockernut hickory in descending order, each statistically different in BPM (Fig. 4). The main effect of treatment suggested that an increase in heat flux density from 0.255–0.891MJm−2 to 1.275–1.485MJm−2 increased BPM by approximately 4.7%, regardless of species. The interaction between species and heat flux density suggested that red maple mean BPM increased from 77.25 to 91.88% with increased heat flux density (Fig. 4). This was the only significant difference in mean BPM between heat flux density ranges within a single species. Red maple’s 91.88% mean BPM at 1.275–1.485MJm−2 was the highest mean, but this mean did not differ from chestnut oak or scarlet oak at either heat flux density. Mean BPM for mockernut hickory and yellow-poplar at both heat flux densities was not significantly different than red maple’s unburned, control mean PBM.

Functional group bud percent mortality model

The model of functional group was significant (p < 0.0001); however, the main effect of the a priori heat tolerance groups was not significant (p = 0.1892). Pyrophytic species mean BPM values did not differ significantly from pyrophobic species mean BPM values, but reflected species-specific differences based on traits.

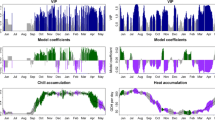

Principal component analysis

The combined component percentage was highest (99.4%) using bud length, diameter, and surface area as independent variables (Fig. 5). From the linear regressions that were evaluated, Component 1 was most related to bud surface area (r2 = 0.99) and Component 2 was most related to bud length (r2 = 0.88). This was additionally confirmed by the formatted loading matrix analysis (Table 2).

Principal component analysis for bud percent mortality by species: A Clusters were established for (1) mockernut hickory (green dots); (2) red maple (purple dots), chestnut oak (blue dots), scarlet oak (orange dots), and yellow-poplar (brown dots); (3) American beech (red dots). B Bud length, surface area, and diameter were utilized as independent variables to generate the highest total component percentage

Discussion

Species responses

Bud tolerance to heat doses varied by species but did not track expected patterns of pyrophytic and phyrophobic groupings defined by other plant traits in previous studies (Fig. 3). For trait-based bud mortality, patterns appear more complex than suggested categories for “pyrophytes” defined by other traits, such as bark or litter (Varner et al. 2016). The species-specific patterns found here not only challenge the original hypothesis that large buds would be more tolerant of heat due to thermal inertia, but may also point to more nuance in the fine scale heat transfer of compound buds, regardless of moisture content or size. Moreover, bud mortality only increased as heat dosage increased for red maple (Fig. 4), suggesting that (a) the doses tested here interacted with other characteristics of the buds or the convective heat transfer to drive mortality or (b) the doses did not represent sufficient range to elicit more distinct responses.

The high mean BPM values for chestnut and scarlet oak (Fig. 4) were unexpected given these species’ characterization as pyrophytes (Loomis 1977; Ward and Stephens 1989). The characterization of heat tolerance for a given species has largely been determined by traits such as bark thickness, which generally becomes more apparent as trees age (Kidd and Varner 2019). Also, litter properties are generally related to flammability and fire propagation (Varner et al. 2015) in designating fire adapted species. In this study, the expectation that certain physical traits of terminal buds from lateral branches would be associated with approximate fire tolerance was not supported. For example, mockernut hickory bud mass was greatest among the species selected for this study (i.e., nearly 13 times greater than red maple) (Table 1). A logical assumption might be that increased bud mass is related to increased bud heat tolerance. This assertion, however, was not reflected in the data (Fig. 4). Additionally, the pointed, narrow surface of American beech buds was hypothesized to be a feature that might increase bud susceptibility to heat damage by increasing surface area to volume ratios. This too, however, was not reflected in the collected data (Fig. 4) as American beech displayed relatively high heat tolerance when compared to the other species.

The principal component analysis suggested that both bud surface area and length provided strong distinctions between American beech and mockernut hickory (Fig. 5). However, a rather large grouping became indistinguishable for the remaining species. Red maple, chestnut oak, and scarlet oak all produce clustered buds; therefore, their association seems logical. Perhaps, the fluid dynamics of heat transfer and flow promoted by clustering are similar, regardless of species, which has not been explored in wildland fire but has a basis in fluid dynamics (Zdravkovich 1987). However, the inclusion of yellow-poplar in this grouping with the principal component analysis counters this logic as that species does not possess clustered buds. Yellow-poplar does possess a bud composed of pre-emergent leaves and perhaps that architecture is more sensitive to heating. The inclusion of additional species in this experiment may have further differentiated this large cluster, particularly in light of the drastic physical differences between American beech and mockernut hickory.

Field applications

Prescribed fires are often conducted in the eastern United States to target specific, undesired vegetative species. In many cases, these fires are conducted at frequencies and intensities that affect understory and mid-story tree stems (Waldrop and Goodrick, 2012). In hardwood ecosystems, seasonal burn patterns are concentrated in leaf-off conditions (Knapp et al. 2009), and topkill through bud mortality may play a significant role in determining successful burn outcomes. A primary motivation of this study was to determine if species-specific differences existed for aerial bud heat tolerance. In particular, a desired outcome was to determine if current assumptions of heat tolerance for other tree tissues and organs could be applied to aerial buds. If aerial bud tolerance could be understood, predicted, and modeled, prescribed fires may be planned for specific conditions that favor topkill or outright mortality of one species over another. Based upon this experiment alone, information regarding species-specific aerial bud heat tolerance is complex and inconsistent with other traits that typically characterize fire tolerance. This study does suggest that aerial bud heat tolerances vary by species and may represent important variation outside of the presumed designations of pyrophytic and pyrophobic.

The results of this study should be interpreted with a few considerations. Post-fire stem vitality and resprouting potential were not fully assessed as part of this study. For example, basal buds are a primary structure angiosperms utilize to regenerate post-fire (Clarke et al. 2012). Their viability and capacity to generate new stems were not measured as part of this endeavor. An additional mechanism that was not assessed in this study is the height to the first branch for each of the mid-story stems sampled. Differences in this height may differ by species and serve as a mechanism to avoid heating of aerial buds (Balfour and Midgley 2006; Bond 2008; Burrows et al. 2008; Higgins et al. 2000); therefore, the mortality of a given aerial bud may not be based solely upon the specific variables that were measured.

This experiment was designed for and conducted in a laboratory with calculated and expected differences in BPM based upon differences in height above a propane burner and differences in heat exposure time, similar to seed trials (Wiggers et al. 2017). The heights and exposure times selected were chosen to mimic potential prescribed burn scenarios in the southeastern United States used to topkill hardwood species in the dormant season (in terms of both heat exposure times and distance to flames). The selection of different heights above the propane burner, heat exposure times, and season of the year may have yielded different results within and between species.

Variation in heat fluxes, rather than the total energy, may be critical to understanding dose responses of buds to heat exposure during a fire, as exposure to energy produced by flaming combustion can produce rapid alternations of convective heating and cooling (Frankman et al. 2012). As such, we must consider whether an individual bud’s response in a field-based scenario may differ from those exposed to the propane burner’s rate of constant gas flow and flux density. Based upon localized fire behavior, fire environment variables (such as weather and fuels), convective cooling, and a given bud’s position (both aboveground and relative to its specific orientation on a given tree stem or branch), a specific bud may respond differently in-the-field when subjected to heat fluxes from prescribed fire for similar times at relatively the same height above flames (O’Brien et al. 2018; Yedinak et al. 2018; Frankman et al. 2012). Alternatively, species with litter that impedes flammability may logically possess buds more tolerant to heat exposure as a survival mechanism.

The choice to measure cell electrolyte leakage to assess BPM was an attempt to more thoroughly assess a percentage of dead tissue as opposed to a binary status of “live” or “dead” post-heating. A more common binary assessment of mortality may have been achieved by applying tetrazolium chloride to the base of heated buds (Lopez Del Egido et al. 2017; Ruf and Brunner 2003) and could be another way to assess overall bud vitality and viability post-heating (Wiggers et al. 2017). Due to the sensitivity of electrical conductivity measurements, no blackened or charred buds were assessed. Therefore, future laboratory experiments could be expanded to include both additional methodologies, species, seasons, and heating conditions to more acutely refine the responses noted in this work.

Our results suggested that aerial buds expressed different levels of heat tolerance. Furthermore, this tolerance is complex and may not easily be defined by commonly used fire tolerance categories (based upon other stem features) nor aerial bud physical traits. It did appear that clustered buds were more sensitive to increasing heat flux density than non-clustered buds, which points toward potential fluid flow around small stem boundary layers and differences in convective energy deposition as a mechanism for these patterns. Additional research in field-based, prescribed fire scenarios using the same species and others in conjunction with additional testing procedures may provide additional insight regarding potential differences between buds of different species, shapes, and sizes. With this information, prescribed fire managers and practitioners may be better equipped to develop enhanced predictive tools to approximate species-specific stem mortality and to better achieve burn-specific objectives.

Conclusion

Vegetative fire tolerance has been a topic of focused research interest. Specific vegetative traits, such as bark thickness and litter flammability, have been measured for specific species, but topkill of stems is a critical mechanism for understanding ecological outcomes of fire that may be dependent on bud mortality. While functional groups have been assigned to trees based upon these traits, tree buds have generally not been directly related to these groups and may play a more critical role in survivorship of stems and branches exposed to surface fires. Based upon bud heating results from six total tree species (three pyrophytes and three pyrophobes) and six heat dosages (which were evaluated statistically as two heat flux densities), species-specific bud mortality was measured. Pyrophytes did not display higher heat tolerance than pyrophobes. Chestnut oak and scarlet oak buds displayed high percent mortality at both exposure times and did not differ from red maple at the highest exposure time. Therefore, some evidence suggests that clustered buds may exhibit less heat tolerance than single buds, but this is inconclusive given yellow-poplar's relatively low percent mortality results at both heat flux densities. This species’ response may be related to its unique bud architecture. Future investigations of these species and others during actual prescribed burns may provide an enhanced perspective on the relative contribution of bud characteristics to stem heat tolerance.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Agee, J.K. 1993. Fire Ecology of Pacific Northwest Forests. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Alexander, H.D., and M.A. Arthur. 2014. Increasing red maple leaf litter alter decomposition rates and nitrogen cycling in historically oak-dominated forests of the eastern US. Ecosystems 17: 1371–1383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-014-9802-4.

Arthur, M.A., H.D. Alexander, D.C. Dey, C.J. Schweitzer, and D.L. Loftis. 2012. Refining the oak-fire hypothesis for management of oak-dominated forests of the eastern United States. Journal of Forestry 110 (5): 257–266.

Balfour, D.A., and J.J. Midgley. 2006. Fire induced stem death in an African acacia is not caused by canopy scorching. Austral Ecology 31: 892–896. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993-2006.01656.x.

Belcher, C.M. 2016. The influence of leaf morphology on litter flammability and its utility for interpreting palaeofire. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 371 (1696): 20150163. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0163.

Blackhall, M., E. Raffaele, J. Paritsis, F. Tiribelli, J.M. Morales, T. Kitzberger, J.H. Gowda, and T.T. Veblen. 2017. Effects of biological legacies and herbivory on fuels and flammability traits: a long-term experimental study of alternative stable states. Journal of Ecology 105: 1309–1322. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12796.

Boerner, R.E.J., T.A. Coates, D.A. Yaussy, and T.A. Waldrop. 2008. Assessing ecosystem restoration alternatives in Eastern deciduous forests: the view from belowground. Restoration Ecology 16: 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-100X.2007.00312.x.

Bond, W.J. 2008. What limits trees in C4 grasslands and savannas? Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 39: 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(00)02033-4.

Brose, P.H., and T.A. Waldrop. 2006. Fire and the origin of Table Mountain pine – pitch pine communities in the southern Appalachian Mountains, USA. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 36: 710–718. https://doi.org/10.1139/x05-281.

Burrows, G.E., S.K. Hornsby, D.A. Waters, S.M. Bellairs, L.D. Prior, and D.M.J.S. Bowman. 2008. Leaf axil anatomy and bud reserves in 21 Myrtaceae species from northern Australia. International Journal of Plant Sciences 169: 1174–1186. https://doi.org/10.1086/591985.

Carpenter, D.O., M.K. Taylor, M.A. Callaham, J.K. Hiers, E.L. Loudermilk, J.J. O’Brien, and N. Wurzburger. 2021. Benefit or liability? The ectomycorrhizal association may undermine tree adaptations to fire after long-term fire exclusion. Ecosystems 24 (5): 1059–1074.

Clarke, P.J., M.J. Lawes, J.J. Midgley, B.B. Lamont, F. Ojeda, G.E. Burrows, N.J. Enright, and K.J.E. Knox. 2012. Resprouting as a key functional trait: how buds, protection and resources drive persistence after fire. New Phytologist 197 (1): 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12001.

Coates, T.A., A. Johnson, W.M. Aust, D.L. Hagan, A.T. Chow, and C. Trettin. 2020. Forest composition, fuel loading, and soil chemistry resulting from 50 years of forest management and natural disturbance in two southeastern Coastal Plain watersheds, USA. Forest Ecology and Management 473: 118337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118337.

Conover, W.J. 1971. Practical nonparametric statistics. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Copenheaver, C.A., J.M. Matthews, J.M. Showalter, and W.E. Auch. 2006. Forest stand development patterns in the southern Appalachians. Northeastern Naturalist 13 (4): 477–494 https://www.jstor.org/stable/4130983.

Dove, N.C., and S.C. Hart. 2017. Fire reduces fungal species richness and in situ mycorrhizal colonization: a meta-analysis. Fire Ecology 13: 37–65. https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.130237746.

Eberhardt, T.L. 2013. Longleaf pine inner bark and outer bark thicknesses: measurement and relevance. Southern Journal of Applied Forestry 37 (3): 177–180. https://doi.org/10.5849/sjaf.12-023.

Frankman, D., B.W. Webb, B.W. Butler, D. Jimenez, J.M. Forthofer, P. Sopko, K.S. Shannon, J.K. Hiers, and R.D. Ottmar. 2012. Measurements of convective and radiative heating in wildland fires. International Journal of Wildland Fire 22 (2): 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF11097.

Hammond, D.H., J.M. Varner, J.S. Kush, and Z. Fan. 2015. Contrasting sapling bark allocation of five southeastern USA hardwood tree species in a fire prone ecosystem. Ecosphere 6 (7): 112. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES15-00065.1.

Hiers, J.K., J.J. O’Brien, R.J. Mitchell, J.M. Grego, and E.L. Loudermilk. 2009. The wildland fuel cell concept: an approach to characterize fine-scale variation in fuels and fire in frequently burned longleaf pine forests. International Journal of Wildland Fire 18 (3): 315–325.

Hiers, J.K., R. Wyatt, and R.J. Mitchell. 2000. The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective? Oecologia 125 (4): 521–530.

Higgins, S.I., W.J. Bond, and W.S.W. Trollope. 2000. Fire, resprouting and variability: a recipe for grass-tree coexistence in savanna. Journal of Ecology 88: 679–686. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2745.2000.00435.x.

Ilik, P., A.M. Pundova, and A.M. Icner. 2018. Estimating heat tolerance of plants by ion leakage: a new method based on gradual heating. New Phytologist 3: 1278. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15097.

Jeffrey M., Kane J. Morgan, Varner J. Kevin, Hiers (2008) The burning characteristics of southeastern oaks: Discriminating fire facilitators from fire impeders. Forest Ecology and Management 256(12) 2039-2045 S0378112708005884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.07.039.

Jolliffe, I. 2005. Principal component analysis. Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science. https://doi.org/10.1002/0470013192.bsa501

Kane, J.M., J.M. Varner, and J.K. Heirs. 2008. The burning characteristics in southeastern oaks: Discriminating fire facilitators from fire impeders. Forest Ecology and Management 258: 2039-2045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.07.039.

Keeley, J.E., J.G. Pausas, P.W. Rundel, W.J. Bond, and R.A. Bradstock. 2011. Fire as an evolutionary pressure shaping plant traits. Trends in Plant Science 16 (8): 406–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2011.04.002.

Kidd, K.R., and J.M. Varner. 2019. Differential relative bark thickness and aboveground growth discriminates fire resistance among hardwood sprouts in the southern Cascades, California. Trees 33: 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-018-1775-z.

Knapp, E.E., B.L. Estes, and C.N. Skinner. 2009. Ecological effects of prescribed fire season: a literature review and synthesis for managers, JFSP Synthesis Reports. Vol. 4 https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=jfspsynthesis.

Kreye, J.K., J.M. Varner, G.W. Hamby, and J.M. Kane. 2018. Mesophytic litter dampens flammability in fire-excluded pyrophitic oak-hickory woodlands. Ecosphere 9 (1): e02078. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2078.

Lafon, C.W., A.T. Naito, H.D. Grissino-Mayer, S.P. Horn, and T.A. Waldrop. 2017. Fire history of the Appalachian region: a review and synthesis, Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-219. Asheville: USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/gtr/gtr_srs219.pdf.

Loomis, R.M. 1977. Wildfire effects on oak-hickory forest in southeast Missouri, Res. Note NC-219, 6. St. Paul: USDA Forest Service North Central Forest Experiment Station.

Lopez Del Egido, L., D. Navarro-Miró, V. Martinez-Heredia, P.E. Toorop, and P.P.M. Iannetta. 2017. A spectrophotometric assay for robust viability testing of seed batches using 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride: using Hordeum vulgare L. as a model. Frontiers in Plant Science 8: 747. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00747.

Loudermilk, E.L., G.L. Achtemeier, J.J. O’Brien, J.K. Hiers, and B.S. Hornsby. 2014. High-resolution observations of combustion in heterogeneous surface fuels. International Journal of Wildland Fire 23 (7): 1016–1026.

Melvin, M. 2018. 2018 National prescribed fire use survey report, Technical Report 03-18, 23. Coalition of Prescribed Fire Councils, Inc. Newton, GA, USA. https://www.stateforesters.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/2018-Prescribed-Fire-Use-Survey-Report-1.pdf.

Nowacki, G.J., and M.D. Abrams. 2008. The demise of fire and “mesophication” of forests in the eastern United States. BioScience 58 (2): 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1641/B580207.

O’Brien, J.J., J.K. Hiers, J.M. Varner, C.M. Hoffman, M.B. Dickinson, S.T. Michaletz, E.L. Loudermilk, and B.W. Butler. 2018. Advances in mechanistic approaches to quantifying biophysical fire effects. Current Forestry Reports 4: 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-018-0082-7.

Pausas, J.G. 2015. Bark thickness and fire regime. Functional Ecology 29: 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12372.

Peixoto, M.D., and R.F. Sage. 2016. Improved experimental protocols to evaluate cold tolerance thresholds in Miscanthus and switchgrass rhizomes. GCB Bioenergy 8 (2): 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.12301.

Ruf, M., and I. Brunner. 2003. Vitality of tree fine roots: reevaluation of the tetrazolium test. Tree Physiology 23 (4): 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/23.4.257.

Ruswick, S.K., J.J. O'Brien, and D.P. Aubrey. 2021. Carbon starvation is absent regardless of season of burn in Liquidambar styraciflua L. Forest Ecology and Management 479: 118588.

Smith, A.M., A.M. Sparks, C.A. Kolden, J.T. Abatzoglou, A.F. Talhelm, D.M. Johnson, L. Boschetti, J.A. Lutz, K.G. Apostol, K.M. Yedinak, and W.T. Tinkham. 2016. Towards a new paradigm in fire severity research using dose–response experiments. International Journal of Wildland Fire 25 (2): 158–166.

USDA FEIS. 2020. https://www.feis-crs.org/feis/. Accessed 19 Jan 2020.

U.S. Climate Data. 2021. https://www.usclimatedata.com/climate/blacksburg/virginia/united-states/usva0068. Accessed February 9, 2021.

Van der Yacht, A.L., S.A. Barrioz, P.D. Keyser, C.A. Harper, D.S. Buckley, D.A. Buehler, and R.D. Applegate. 2017. Vegetation response to canopy disturbance and season of burn during oak woodland and savanna restoration in Tennessee. Forest Ecology and Management 390: 187–202.

Van Lear, D.H., W.D. Carroll, P.R. Kapeluck, and R. Johnson. 2005. History and restoration of the longleaf pine-grassland ecosystem: implications for species at risk. Forest ecology and Management 211: 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2005.02.014.

Varner, J.M., J.M. Kane, J.K. Hiers, J.K. Kreye, and J.W. Veldman. 2016. Suites of fire-adapted traits of oaks in the southeastern USA: multiple strategies for persistence. Fire Ecology 12 (2): 48–64.

Varner, J.M., J.M. Kane, J.K. Kreye, and E. Engber. 2015. The flammability of forest and woodland litter: a synthesis. Current Forestry Reports 1: 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40725-015-0012-x.

Vinson, J.A., S.M. Barrett, W.M. Aust, and M.C. Bolding. 2017. Evaluation of bladed skid trail closure methods in the Ridge and Valley Region. Forest Science 63 (4): 432–440. https://doi.org/10.5849/FS.2016-030R1.

Violle, C., M.L. Navas, D. Vile, E. Kazakou, C. Fortunel, I. Hummel, and E. Garnier. 2007. Let the concept of trait be functional! Oikos 116 (5): 882–892. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15559.x.

Waldrop, T.A., Goodrick, S.L. 2012. (Slightly revised 2018). Introduction to prescribed fires in Southern ecosystems. Science Update SRS-054. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Research Station. p. 80. https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/su/su_srs054.pdf.

Ward, J.S., and G.S. Stephens. 1989. Long-term effects of a 1932 surface fire on stand structure in a Connecticut mixed hardwood forest. In Proceedings, 7th central hardwood conference; 1989 March 5-8; Carbondale, IL. Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-132, ed. George Rink and Carl A. Budelsky, 267–273. St. Paul: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station.

Wiggers, M.S., J.K. Hiers, A. Barnett, R.S. Boyd, and L.K. Kirkman. 2017. Seed heat tolerance and germination of six legume species native to a fire-prone longleaf pine forest. Plant Ecology 218 (2): 151–171.

Yedinak, K.M., E.K. Strand, J.K. Hiers, and J.M. Varner. 2018. Embracing complexity to advance the science of wildland fire behavior. Fire 1 (2): 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire1020020.

Zdravkovich, M.M. 1987. The effects of interference between circular cylinders in cross flow. Journal of Fluids and Structures 1 (2): 239–261.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the following individuals for field and laboratory assistance: Heaven Aziz, Christen Beasley, Nick Boley, Keith Coates, George Hahn, Andrew Johnson, Trevor Pauley, and Tal Roberts. We would additionally like to thank two anonymous peer-reviewers for their comments on earlier versions of this manuscript that greatly improved its content and quality.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (Project Number RC19-C1-1119). Publication funding was provided by the Virginia Tech Open Access Subvention Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ABM: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization; TAC: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization; JKH: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; JRS: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing; JJO: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing; CMH: conceptualization, writing—review and editing. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McClure, A.B., Coates, T.A., Hiers, J.K. et al. Estimating heat tolerance of buds in southeastern US trees in fire-prone forests. fire ecol 18, 32 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-022-00160-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42408-022-00160-5