Abstract

Background

The inventory process is the first method to protect and safeguard animal biodiversity. This study carries out a quantitative and qualitative inventory of terrestrial gastropods at three sites in Skikda province (north-eastern Algeria). The relationship between terrestrial gastropod diversity and soil physicochemical factors was investigated using statistical analyses.

Results

The inventory data reveals the presence of four families and eight species showing varied predominance rates of Cornu aspersum species according to each site in the city of Skikda (Azzaba 53.88%; Ben-Azzouz 56.12%; El-Hadaiek 37.92%). The maximal specific richness was registered in the El-Hadaiek site (seven species), and the highest mean richness was noted in the Ben-Azzouz site (392 individuals). Of the eight gastropod species identified, three species (Cornu aspersum, Cantareus apertus and Rumina decollate) were classified as constant species. The Shannon–Weaver diversity and equitability indices vary by site.

Conclusion

The presence of certain species in one site and their absence in other sites, as well as the variation in ecological indices, could be attributed to the effect of soil-physicochemical factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Human industrial and agricultural activities and increasing population growth rates, as well as economic and technological factors, have negatively impacted biodiversity (Aronson et al., 2014; Douglas et al., 2013; Gaston et al., 2013; Mackenzie & Michael, 2018; Yanes, 2012) by inducing marked changes in the structure of biological behaviours and the dysfunction of surrounding ecosystems (Chen & Blume, 1997; Sha et al., 2015). Interestingly, land snails play a crucial role in the functioning and stability of ecosystems due to their contribution to the provision of food for other animals, decomposition of plant material and maintenance of soil calcium content (Lange, 2003). Additionally, their short lifetime and limited dispersal ability make them excellent bioindicators (Watters et al., 2005). Furthermore, snails and slugs can be important links in the transfer of chemicals from vegetation or plant litter to carnivores (Coughtrey et al., 1979; Nica et al., 2012, 2013). Consequently, such transfer along food chains is an important eco-toxicological aspect (Laskowski & Hopkin, 1996). Several studies on land snail inventories have been carried out in several biotopes of Algeria, notably in the north-western (Damerdji, 2008, 2013) and north-eastern regions (Larbaa & Soltani, 2013; Douafer & Soltani, 2014). Recently, a survey of gastropods was conducted in five areas of north-eastern Algeria (Belhiouani et al., 2019). However, we are not aware of a study on the biodiversity and abundance of terrestrial gastropods in other areas of northeast Algeria. The Skikda region (north-eastern Algeria) is the location of highly developed petrochemical industries, which cause serious risks to human and environmental safety by progressively destroying natural resources, water and air quality (Fadel et al., 2016; Kahoul et al., 2014; Zeghdoudi et al., 2019). Researching the biotic and abiotic factors that influence land diversity and abundance is essential to prevent and protect terrestrial ecosystem. Many researchers have demonstrated that climatic factors, soil physicochemical factors and plant communities affect the distribution and abundance of terrestrial gastropods (Gärderforns et al., 1995; Lewis Najev et al., 2020; Nekola, 2003). In Algeria, several studies have been conducted on the effect of environmental factors on the diversity and abundance of land snails (Belhiouani et al., 2019; Douafer & Soltani, 2014). The present study aims to (1) identify and investigate the abundance and diversity of terrestrial gastropod species (snails and slugs) in three sites located in Skikda province, and (2) investigate the relationship between terrestrial gastropod diversity and soil physicochemical factors using statistical analysis (correlation analysis).

Methods

Study areas

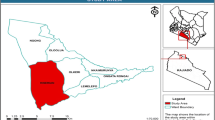

The city of Skikda (36°52′34 N, 6°54′33° E) is located in the north-east of Algeria, 510 km from Algiers (capital of Algeria). It has a Mediterranean climate, characterised by two seasons: a mild, rainy winter and a hot, dry summer. The average annual precipitation varies between 600 and 800 mm/year. The annual temperature varies from 9 in winter to 27 °C in summer. Humidity during the day is about 70% (Souilah et al., 2019). The study was conducted in three cities of Skikda province (Fig. 1): El-Hadaiek covering an area of 271.75 km2, Azzaba extending over an area of 805.34 km2, and Ben-Azzouz, the largest city of the province, with an area covering 228.28 km2. Table 1 lists the characteristics of the three sampling sites.

Sampling methods and taxa identification

Snail sampling was carried out using the quadrat method. Quadrats likely to be suitable breeding habitats for snails and to be sampled were randomly selected by projecting a grid onto a map of the study area. For each site (Fig. 2), a 400 m2 quadrat was established using a tape measure for each sampling site. Snail sampling was carried out by two persons searching each quadrat for 2 h, following the method of Benjamin et al. (2014) with modifications. Live snails and slugs, as well as dead snail shells were collected by hand from different natural habitats (on the ground, under tree trunks, on plants and in crops). All samples obtained were preserved in 70% ethanol at the Laboratory for the Optimization of Agricultural Production in Subhumid Areas (University of Skikda). The snails collected from the three sites were thoroughly identified based on animal morphological features (shape, size, colouration and ornamentation of the shell). Identification was based on the key features reported by Barker (2001) and Bouchet et al. (2005). When a snail was collected, the plant species was noted. Samples of plant species collected in the field were transferred to the laboratory for identification, based on the method previously reported by Quezel and Santa (1962–1963) and Andreas (1998).

Data analysis

The identified snail individuals were counted and subjected to the determination of the constancy index, relative abundance, specific and mean richness, and some diversity indices (Shannon–Weaver and equitability index).

The constancy index (C) is calculated according to Dajoz (1985):

where C is the centesimal frequency, Pa is the total number of samples containing the species considered and P is the total number of samples taken. According to Dajoz (1985), three different categories are distinguished: constant species (C ≥ 50%), accessory species (25% < C < 50%) and accidental species (C ≤ 25%).

The relative abundance (A) index allows to study the distribution of a species in a given region, and to identify the species as common, rare, or very rare species (Dajoz, 1985). It is calculated by the following formula:

where ni is the total number of considered species, and N is the total number of individuals found. According to Dajoz (1985), species can be classified into three different groups: common species (A > 50%), rare species (25% ≤ C ≤ 50%) and very rare species (C < 25%).

The specific richness (S) is the number of species found in the study area (Blondel, 1975; Ramade, 1984).

The mean richness (S′) is defined according to Blondel (1975) and is calculated by the following formula:

where ni is the total number of considered species, and P is the total number of samples taken.

The Shannon–Weaver index (H′) index is calculated by the following equation (Shannon & Weaver, 1963):

where Pi is the relative frequency (ni/N) and R is the total number of species.

The equitability index (E) constitutes a second fundamental dimension of diversity (Ramade, 1984). The equitability is expressed as follows:

Soil sampling and determination of physicochemical parameters

The analysis of soil physicochemical properties was carried out on samples collected manually using a trowel (Koranteng-Addo et al., 2011) to a depth of about 10 cm. Three representative soil samples were collected from each site using the same quadrate method to study molluscs diversity. In brief, the soils were air-dried for 3- 6 days, crushed and sieved through a 2 mm diameter sieve and then stored in a non-metallic container. Soil pH is measured in soil–water suspension (soil/water ratio = 1/2.5) according Gauchers (1968). The electrical conductivity (EC) can be determined on a soil extract (soil/water ratio = 1/5) using a conductivity meter (Delaunois, 1976). Organic matter (OM) was quantified by the method proposed by Anne (1945), based on the determination of the percentage of organic carbon in the soil. This method is based on the oxidation of organic carbon with potassium bicarbonate and titration of the solution with Mohr salt (0.2 N). The determination of total limestone was calculated according to the method of Duchaufour (1970) based on the reaction of calcium carbonate with hydrochloric acid (HCl). The total porosity (P) is calculated from the apparent and true densities. Soil field capacity was determined using the software of Saxton et al. (1986), while soil humidity (H) was calculated from the difference between the weight of wet soil and dry soil using a precision balance.

Statistical analysis

Data are displayed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons of physicochemical factors were tested for statistical significance by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. The relationship between the specific richness of terrestrial gastropods and the physicochemical characteristics of the soils was also examined using the Pearson correlations test. Statistical tests were performed using MINITAB software (version 16, Penn State College, PA, USA) where p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Gastropod species inventory

The inventory of terrestrial gastropods carried out at the three selected sites reveals the presence of eight species belonging to four malacological families (Milacidae, Helicidae, Geomitridae and Achatinidae). Table 2 summarises the species inventoried in accordance with previously reported classification criteria (Bonnet et al., 1990; Chevallier, 1992; Germain, 1969). The results show that each of the gastropod families Milacidae and Helicidae includes two species; Geomitridae includes three species, and Achatinidae includes one species.

Flora inventory

For the flora inventory in the study sites, lists of plant species were made (Table 3). In all study areas, 12 species belonging to 12 families were identified. Furthermore, we observed that there was no difference in plant species between the three sampling sites and that there was no relationship between snail diversity and plant richness.

Terrestrial gastropod structure and distribution in the study sites

As shown in Table 4, the species Cornu aspersum presents minimal and maximal abundance rates in El-Hadaiek (37.92%) and Ben-Azzouz (56.12%), as well as maximal and minimal values in Ben-Azzouz (25%) and El-Hadaiek (2.92%). Slugs present a very low abundance (2.04%) in El-Hadaiek and zero-abundance in Azzaba and Ben-Azzouz. In accordance with the findings reported by Dajoz (1985), the constancy values obtained (C%) show the presence of 100% of the species Cornu aspersum, Cantareus apertus and Rumina decollata in the three selected sites. They are therefore considered as constant species (C ≥ 50%). Similarly, Cernuella virgata was found as a constant species in El-Hadaiek and Ben-Azzouz, and as an accessory species in Azzaba (25% < C < 50%), while the species Cochlicella barbara is constant in El-Hadaiek and accessory in Ben-Azzouz and Azzaba. Furthermore, the species Trochoidea elegans was found as a very accidental species in El-Hadaiek and Azzaba (C ≤ 50%) and accessory species in Ben-Azzouz. Slugs are constant in El-Hadaiek and very accidental in Azzaba and Ben-Azzouz.

Biodiversity indices

The specific richness is represented by seven, six and five gastropod species in El-Hadaiek, Ben-Azzouz and Azzaba respectively (Table 5). However, the maximal values of the mean richness are 392 and 366.5 in Ben-Azzouz and Azzaba respectively (Table 5). As indicated in Table 5, the Shannon–Weaver (H′) diversity index varies between 0.51 in Ben-Azzouz and 0.68 in El-Hadaiek. The equitability index (E) is defined as the fundamental dimension of diversity enabling the comparison of population structure. Thus, the results obtained show that the values of the equitability index vary between 0.28 and 0.35.

Soil physicochemical characteristics

The physicochemical parameters studied (organic matter, field capacity, permeability and porosity) vary significantly between the three sites (Table 6). The one-way ANOVA (site) of the soil physicochemical parameters reveals a highly significant effect of site on field capacity (F2,6 = 42.21, p < 0.001), organic matter (F2,6 = 20.67, p < 0.01) and permeability (F2,6 = 50.82, p < 0.001). The site effect on porosity was found significant (F2,6 = 6.66, p < 0.05). Pairwise comparisons (Tukey’s test) of the variation in soil physicochemical parameters reveal a significant difference (p < 0.05) between the sites (Table 5).

Relationship between specific richness and soil physicochemical characteristics

The correlation between the specific richness and physicochemical soil characteristics in all study sites was analysed (Table 7). A highly significant correlation only between the specific richness and organic matter (R = 0.904, p < 0.001) and field capacity (R = 0.956, p < 0.01) can be noted. In contrast, specific richness shows a highly significant negative correlation (R = −0.888, p < 0.001) with permeability. A significant negative correlation is observed between the specific richness and porosity (R = −0.783, p < 0.05).

Discussion

This study investigated the abundance and diversity of terrestrial gastropod species at three sites located in Skikda province, as well as the impacts of soil physic-chemical factors on snail diversity, was examined. The results revealed an important diversity of the malacological fauna in Skikda province, particularly in the city of El-Hadaiek, and differences in ecological indices (constancy index, relative abundance, specific and mean richness, Shannon–Weaver and equitability indices) between the selected study sites. Furthermore, the soil at the El-Hadaiek site was found to be characterised by high organic matter and field capacity and low porosity and permeability. The results suggest that these parameters are important in determining the richness of terrestrial gastropods in Skikda province, and we do not rule out that other environmental factors may also be important. The biodiversity and distribution of land snails depend on several factors, such as soil characteristics (André, 1982; Douafer & Soltani, 2014; Ondina et al., 1998), climatic factors (Ameur et al., 2019; Hermida et al., 1994), anthropogenic disturbances (Belhiouani et al., 2019) and vegetation (Damerdji, 2013; Damerdji & Amara, 2013; Ondina & Mato, 2001).

Several studies have evidenced the need to protect mollusc biodiversity on a global scale (N’dri et al., 2016; Hallgass & Vannozzi, 2016; Nicolai & Ansart, 2017; Heiba et al., 2018; Desoky, 2018; Dedov et al., 2018; Borreda & Martinez-Orti, 2017). In Algeria, some inventories of terrestrial gastropods have been recently carried out in different biotopes (Bouaziz-Yahiatene & Medjdoub-Bensaad, 2016; Hamdi-Ourfella & Soltani, 2016; Ramdini et al., 2021). In the present study, specific richness was lower in the sites of Ben-Azzouz and Azzaba than in El-Hadaiek. Similarly, specific richness is expressed by seven, six and five species respectively at El-Hadaiek, Ben-Azzouz and Azzaba respectively. Previous studies conducted in the northern-eastern region of Algeria have revealed 13 species of terrestrial pulmonate gastropods in El-Kala, El Hadjar and Sidi Kassi (Larba & Soltani, 2013). In addition, Helicidae has been identified as the most abundant family in all three sites with high percentages in Ben-Azzouz and Azzaba, and this is in line with previous results on biodiversity in eastern Algeria (Douafer & Soltani, 2014). This dominance is explained by Chevallier (1992) who assumes the action of the cool and humid environment and selected dark varieties.

The abundance results show that Cornu aspersum is a common species in all the study sites (El-Hadaiek, Azzaba and Ben-Azzouz). Moreover, the results of species constancy indicate that the species Cornu aspersum, Cantareus apertus and Rumina decollata are constant in the three study sites (100%) with a significant biomass and a potential for species adaptation via different climates and soils, since the other species present variable constants in various sites. In this regard, Damerdji (2008) reported three constant species and four accidental species in Tlemcen (southern Algeria). The author also reported (Damerdji & Amara, 2013) that the specific richness equals four species (two constants, one accessory, and one accidental) in the region of Naâma (southwestern Algeria).

The diversity of the Shannon–Weaver index is lower in El-Hadaiek (0.68 bits) compared to that noticed in El-Kala site (3.05 bits) (Douafer & Soltani, 2014). Also, the equitability index varies between 0.35 and 0.28 (< than 1), suggesting that the distribution of different gastropod species is not in equilibrium with each other (Ramade, 1984). Similar results were obtained in the city of Tlemcen (Northwest Algeria) by Damerdji (2008), while the regions of El Hadjar, Sidi Kaci and El-Kala located in the Northeast Algeria presents an equitability index superior to 0.50 (Larba & Soltani, 2013). This is probably related to the differences in environmental variables between the sites.

The distribution and activity of land snails depend on several factors, such as soil characteristics (André, 1982; Gärderforns et al., 1995; Ondina et al., 1998), climatic factors (Hermida et al., 1994) and vegetation (Lewis Najev et al., 2020; Nekola, 2003; Ondina & Mato, 2001). With regard to mollusc nutrition, the flora inventory shows the proliferation of gastropods on all botanical species of the study sites. Several studies have shown a correlation between vegetation and mollusc distribution (Barker & Mayhill, 1999; Millar & Waite, 2002; Martin & Somer, 2004). However, in this study, no relationship was found between the distribution of land snails and dominant plant species in the three study sites. According to the work of Nunes and Santos (2012) conducted in the forests of Ilha (Brazil), this result could be explained by the homogeneity of the study area.

Physicochemical factors influence snail diversity in three study sites containing organic matter, field capacity, porosity and permeability. Correlation analysis reveals that organic matter and field capacity are positively correlated with snail specific richness. However, a negative correlation is noted between this parameter (specific richness) and two soil physicochemical factors (permeability and porosity). Organic matter (OM) in the soil provides essential nutrients for plant growth and influences the soil's ability to retain moisture (Chapin et al., 2002) and can also positively affect the abundance of terrestrial gastropods. In this study, the OM content in the soils of the three sites is > 5%, and thus the soils become very rich in organic matter (Abiven et al., 2009), as was found in El-Hadaiek (13.75 ± 0.47%) study area.

On the other hand, the field capacity (the maximum volume of water that a soil can retain) is very high at El-Hadaiek (36.07 ± 4.01) compared to the other sites (Azzaba and Ben-Azzouz). This parameter is related to soil texture (amount of clay), which is the most important factor affecting the distribution of gastropods (Outeiro et al., 1993). The soils of the El-Hadaiek and Ben-Azzouz sites are characterised by a clayey-silt texture, while the silt–clay texture characterises the Azzaba site. The clayey-silt soils retain more water than silt–clay soils with a particulate structure. The porosity follows the granulometric nature of the soil; in clay soils (e.g., El Hadaiek), the porosity value is on average ≤ 50.

In the other two sites (Azzaba and Ben-Azzouz) where there is less clay, the porosity is around 50%. The presence of clay clogs porous spaces and slows down the circulation of water in the soil. Water circulation (permeability) is slowed down in soils with low porosity, as in the case of El-Hadaiek site (0.25 ± 0.02 cm/h). This is because when soil permeability decreases, the soil pores are filled with water, resulting in higher humidity. Moisture is necessary for the respiration and reproduction of land snails (Coney et al. 1982) and for the production of mucus which is essential for locomotion (Cameron, 2009). These results are similar to those obtained by Millar and Waite (2002), Martin and Sommer (2004), Tattersfield et al. (2006) and Horsák et al. (2007).

Conclusion

This paper presented the first inventory of gastropod molluscs in Skikda province. It aims to protect terrestrial ecosystems and preserve biodiversity. The study showed that this region has an important malacofauna like other regions of North-East Algeria. A total of eight species of terrestrial gastropods were reported from three different sites located in this region. The results show that the diversity and abundance of gastropods vary from site to site, due to different physicochemical soil characteristics, including field capacity, permeability, organic matter and porosity.

Availability of data and materials

All data are available.

References

Abiven, S., Menasseri, S., & Chenu, C. (2009). The effect of organic inputs over time on soil aggregate stability—A literature analysis. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 41(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.09.015

Ameur, N., Adjroudi, R., Bachir, A. S., & Mebarkia, N. (2019). Diversity and distribution patterns of land snails in the arid region of Batna (North East Algeria). Ecology, Environment and Conservation, 25, 1517–1523.

André, J. (1982). Les peuplements de mollusques terrestres des formations végétales à Quercus pubescens Willd. Du Montpelliérais. Premiers Résultats. Malacologia, 22, 483–488.

Andreas, B. (1998). Guide des plantes du bassin méditerranéen. Ed. Ulmer.

Anne, P. (1945). Sur le dosage rapide du carbone organique des sols. Annales Agronomiques, 2, 161–172.

Aronson, M. F., La Sorte, F. A., Nilon, C. H., Katti, M., Goddard, M. A., Lepczyk, C. A., Warren, P. S., Williams, N. S., Cilliers, S., Clarkson, B., Dobbs, C., Dolan, R., Hedblom, M., Klotz, S., Kooijmans, J. L., Kühn, I., Macgregor-Fors, I., McDonnell, M., Mörtberg, U., … Winter, M. (2014). A global analysis of the impacts of urbanization on bird and plant diversity reveals key anthropogenic drivers. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.3330

Barker, G. M. (2001). The biology of terrestrial molluscs. CABI Publishing.

Barker, G. M., & Mayhill, P. C. (1999). Patterns of diversity and habitat relationships in terrestrial mollusc communities of the pukeamaru ecological district, northeastern New Zealand. Journal of Biogeography, 26(2), 215–238. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.1999.00267.x

Belhiouani, H., El-Okki, M. H., Afri-Mehennaoui, F. Z., & Sahli, L. (2019). Terrestrial gastropod diversity, distribution and abundance in areas with and without anthropogenic disturbances, Northeast Algeria. Biodiversitas, 20(1), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.13057/biodiv/d200128

Benjamin, O. S., Gizelle, A. B., & Ian Kendrich, C. F. (2014). An updated survey and biodiversity assessment of the land snail (Mollusca: Gastropoda) species in Marinduque, Philippines. Philippine Journal of Science, 143(2), 199–210.

Blondel, J. (1975). L’analyse des peuplements d’oiseaux, éléments d’un diagnostic écologique: La méthode des échantillonnages fréquentiels progressifs (EFP). La Terre Et La Vie, 29(4), 533–589.

Bonnet, J. C., Aupinel, P., & Vrillon, J. L. (1990). L’escargot Helix aspersa, biologie, élevage. INRA Editions; INRA Editions.

Borreda, V., & Martinez-Orti, A. (2017). Contribution to the knowledge of the terrestrial slugs (Gastropoda, Pulmonata) of the Maghreb. Iberus, 35, 1–10.

Bouaziz-Yahiatene, H., & Medjdoub-Bensaad, F. (2016). Malacofauna diversity in Kabylia (Algeria). Advances in Environmental Biology, 10, 99–111.

Bouchet, P., Rocroi, J. P., Frýda, J., Hausdorf, B., Ponder, W., Valdés, A., & Warén, A. (2005). Classification and nomenclator of gastropod families. Malacologia: International Journal of Malacology, 47(1–2), 1–368.

Cameron, R. (2009). The survival, weight-loss and behaviour of three species of land snail in conditions of low humidity. Journal of Zoology, 160(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1970.tb02900.x

Chapin, F. S., Matson, P. A., & Mooney, H. A. (2002). Principles of terrestrial ecosystem ecology. Springer.

Chen, J., & Blume, H. P. (1997). Impact of human activities on the terrestrial ecosystem of Antarctica: A review. Polarforschung, 65(2), 83–92.

Chevallier, H. (1992). L'Elevage des éscargots. Production et préparation du petit-gris. 2nd ed. Edit. Point Veterinaries.

Coughtrey, P. J., Jones, C. H., Martin, M. H., & Shales, S. W. (1979). Litter Accumulation in Woodlands Contaminated by Pb, Zn, Cd and Cu. Oecologia, 39(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00345996

Dajoz, R. (1985). Précis d’Écologie. Dunod.

Damerdji, A. (2008). Contribution à l’étude écologique de la malacofaune de la zone Sud de la région de Tlemcen (Algérie). Afrique Science, 4(1), 138–153. https://doi.org/10.4314/afsci.v4i1.61667

Damerdji, A. (2013). Malacological diversity on some Lamiaceae in the region of Tlemcen (Northwest Algeria). Journal of Life Science, 7(8), 856–861. https://doi.org/10.15744/2639-3336.1.106

Damerdji, A., & Amara, A. (2013). Composition et Structure des Gastéropodes dans les stations à Retama raetam (Fabaceae) dans la Région de Naâma (Algérie). Afrique Science, 9(1), 77–88.

Dedov, I. K., Fehér, Z., Szekeres, M., Schneppat, U. E., & U. E. . (2018). Diversity of Terrestrial Gastropods (Molluscsa, Gastropoda) in the Prespa National Park, Albania. Acta Zoologica Bulgarica, 70(4), 469–477.

Delaunois, A. (1976). Travaux pratiques de pédologie (générale). INRA.

Desoky, A. E. A. S. S. (2018). Identification of terrestrial gastropods species in Sohag Governorate, Egypt. Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science, 3(1), 45–48.

Douafer, L., & Soltani, N. (2014). Inventory of land snails in some sites in the Northeast Algeria: Correlation with soil characteristics. Advances in Environmental Biology, 8(1), 236–243.

Douglas, D. D., Brown, D. R., & Pederson, N. (2013). Land snail diversity can reflect degrees of anthropogenic disturbance. Ecosphere, 4(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES12-00361.1

Duchaufour, P. (1970). Précis de pédologie. Ed Masson et Cie.

Fadel, D., Hadjoudja, N., Badouna, B. E., & Djamaï, R. (2016). Bio-qualitative estimation of diffused air pollution of a city in North-eastern Algeria by using epiphytic lichens. International Journal of Research & Methodology in Social Science, 2(3), 34–43.

Gärderforns, U., Waldén, H. W., & Wäreborn, I. (1995). Effects of soil acidification on forest land snails. Ecological Bulletins, 44, 259–270.

Gaston, K., Bennie, J., Davies, T., & Hopkins, J. (2013). The ecological impacts of nighttime light pollution: A mechanistic appraisal. Biological Reviews, 88(4), 912–927. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12036

Gauchers, G. (1968). Traité de Pédologie Agricole. Le sol et ses caractéristiques agronomiques. Ed. Dunod.

Germain L. (1969). Faune de France, 21, Mollusques Terrestres et Fluviatiles. Office Central de Faunistique. Kraus Reprint. Nendeln, Liechtenstein.

Hallgass, A., & Vannozzi, A. (2016). Terrestrial gastropods (Mollusca Gastropoda) from Lepini Mountains (Latium, Italy): A first contribution. Biodiversity Journal, 7(1), 93–102.

Hamdi-Ourfella, A., & Soltani, N. (2016). Biodiversity of gastropods in Algeria. Helix aperta bioindicator. European university editions.

Heiba, F. N., Mortada, M. M., Geassa, S. N., Atlam, A. I., & Abd El-Wahed, S. I. (2018). Terrestrial gastropods: Survey and relationships between land snail assemblage and soil properties. Journal of Plant Protection and Pathology, 9(3), 219–224.

Hermida, J., Outeiro, A., & Rodríguez, T. (1994). Biogeography of terrestrial gastropods of North West Spain. Journal of Biogeography, 21, 207–217.

Horsák, M., Hájek, M., Tichý, L., & Juricková, L. (2007). Plant indicator values as tool for land mollusc autecology assessment. Acta Oecologica, 32, 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2007.03.011

Kahoul, M., Alioua, A., Derbal, N., & Ayad, W. (2014). Behavior of soil micromycetes regarding the mercury pollution in the area of Azzaba (Algeria). Journal of Materials and Environmental Science, 5(5), 1470–1476.

Koranteng-Addo, E. J., Owusu-Ansah, E., Boamponsem, L. K., Bentum, J. K., & Arthur, S. (2011). Levels of zinc, copper, iron and manganese in soils of abandoned mine pits around the Tarkwa gold mining area of Ghana. Advances in Applied Science Research, 2(1), 280–288.

Lange, C. N. (2003). Environmental factors influencing land snail diversity patterns in Arabuko Sokoke Forest, Kenya. African Journal of Ecology, 41, 352–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.2003.00482.x

Larba, R., & Soltani, N. (2013). Diversity of the terrestrial gastropods in the Northeast Algeria: Spatial and temporal distribution. European Journal of Experimental Biology, 3(4), 209–215.

Laskowski, R., & Hopkin, S. P. (1996). Accumulation of Zn, Cu, Pb and Cd in the garden snail (Helix aspersa): Implications for predators. Environmental Pollution, 91(3), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/0269-7491(95)00070-4

Lewis Najev, B. S., Schofield, A., Flores, R. I., Hutchins, B. T., Andrew, Mcdonald J., & Perez, K. E. (2020). Land snail communities of the lower Rio Grande valley are affected by human disturbance and correlate with vegetation community composition. The Southwestern Naturalist. https://doi.org/10.1894/0038-4909-64.3-4.216

Mackenzie, N. H., & Michael, L. M. (2018). Urbanization impacts on land snail community composition. Urban Ecosystems, 21(4), 721–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-018-0746-x

Martin, K., & Sommer, M. (2004). Relationships between land snail assemblage patterns and soil properties in temperate-humid forest ecosystems. Journal of Biogeography, 31, 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.2003.01005.x

Millar, A. J., & Waite, S. (2002). The relationship between snails, soil factors and calcitic earthworm granules in a coppice woodland in Sussex. Journal of Conchology, 37(5), 483–504.

N’dri, S.C.A., Mamadou, K., Memel J. D., Otchoumou A., & Oke C. O. (2016). Speciesrichness and diversity of terrestrial molluscs (Mollusca, Gastropoda) in Yapo classified forest, Côte d’Ivoire. Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences, 9(1), 133–141.

Nekola, J. C. (2003). Large-scale terrestrial gastropod community composition patterns in the Great Lakes region of North America. Divers Distributions, 9, 55–71.

Nica, D. V., Bordean, D. M., Borozan, A. B., Gergen, I., Bura, M., & Banatean-Dunea, I. (2013). Use of land snails (pulmonata) for monitoring copper pollution in terrestrial ecosystems. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 225, 95–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6470-9_4

Nica, D. V., Bura, M. M., Gergen, I., Harmanescu, M., & Bordean, D. M. (2012). Bioaccumulative and conchological assessment of heavy metal transfer in a soil plant-snail food chain. Chemistry Central Journal, 6(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-153X-6-55

Nicolai, A., & Ansart, A. (2017). Conservation at a slow pace: Terrestrial gastropods facing fast-changing climate. Conservation Physiology, 5(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/conphys/cox007

Nunes, G. K. M., & Santos, S. B. (2012). Environmental factors affecting the distribution of land snails in the Atlantic Rain Forest of Ilha Grande, Angra dos Reis, RJ, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Biology, 72(1), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842012000100010

Ondina, P., & Mato, S. (2001). Influence of vegetation type on the constitution of terrestrial gastropod communities in Northwest Spain. Veliger, 44(1), 8–19.

Ondina, P., Mato, S., Hermida, J., & Outeiro, A. (1998). Importance of soil exchangeable cations and aluminium content on land snail distribution. Applied Soil Ecology, 9, 229–232.

Outeiro, A., Agüera, C., & Parejo, C. (1993). Use of ecological profiles in a study of the relationship of terrestrial gastropods and environmental factors. Journal of Conchology, 34, 365–375.

Quezel, P., & Santa, S. (1962–1963). Nouvelle flore de l’Algérie et des régions désertiques méridionales. Tome 1 et 2. Centre nationale de la recherche scientifique.

Ramade, F. (1984). Elément d’écologie: écologie fondamentale. Mac-Graw-Hill.

Ramdini, R., Bouaziz-Yahiatene, H., & Medjdoub-Bensaad, F. (2021). Diversity of terrestrial gastropods in central-northern of Algeria (Algiers and Boumerdes). Folia Conchyliologica, 60, 25–33.

Saxton, K. E., Rawls, W. J., Romberger, J. S., & Papendick, R. I. (1986). Estimating generalized soil-water characteristics from texture. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 50, 1031–1036. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1986.03615995005000040039x

Sha, Z., Yuefei, H., Bofu, Y., & Guangqian, W. (2015). Effects of human activities on the eco-environment in the middle Heihe River Basin based on an extended environmental Kuznets curve model. Ecological Engineering, 76, 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.04.020

Shannon, C. E., & Weaver, W. (1963). The mathematical theory of communication. University of Ilinois Press.

Souilah, N., Bendif, H., Djamel Miara, M., & Frahtia, A. (2019). Medicinal plants in floristic regions of El Harrouch and Azzaba (Skikda-Algeria): Production and therapeutic effects. Journal of Floriculture and Landscaping, 4, 05–011. https://doi.org/10.25081/jfcls.2018.v4.3770

Tattersfield, P., Seddon, M. B., Ngereza, C., & Rowson, B. (2006). Elevational variation in diversity and composition of land- snail in Tanzanian forest. African Journal of Ecology, 44, 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.2006.00612.x

Watters, G. T., Menker, T., & O’dee, S. H. (2005). A comparison of land snail faunas between strip-mined land and relatively undisturbed land in Ohio, USA—An evaluation of recovery potential and changing faunal assemblages. Biological Conservation, 126(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.05.005

Yanes, Y. (2012). Anthropogenic effect recorded in the live-dead compositional fidelity of land snail assemblages from San Salvador Island Bahamas. Biodiversity and Conservation, 21(13), 3445–3466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-012-0373-4

Zeghdoudi, F., Tanjir, L. M., Ouali, N., Haddidi, I., & Rachedi, M. (2019). Concentrations of trace-metal elements in the superficial sediment and the marine magnophyte, Posidonia oceanica (L.) Delile, 1813 from the Gulf of Skikda (Mediterranean coast, East of Algeria). Cahiers De Biologie Marine, 60, 223–233.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Algerian Fund for Scientific Research (Laboratory for the Optimization of Agricultural Production in Subhumid Areas) and the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research of Algeria (PRFU Projet to Pr. N. Zaidi). We thank Pr. N. Soltani (Laboratory of Applied Animal Biology, University of Annaba) for his advice and Dr. A. Hadef (University of Skikda) for the realization of geographical map.

Funding

No funding was provided.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NZ collected the data, analysed and drafted the MS. LD, AH interpreted data and edited the MS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zaidi, N., Douafer, L. & Hamdani, A. Diversity and abundance of terrestrial gastropods in Skikda region (North-East Algeria): correlation with soil physicochemical factors. JoBAZ 82, 41 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41936-021-00239-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41936-021-00239-6