Abstract

Introduction

As the epidemic of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is rapidly developing in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), the importance of local research capacity and the role of contextually relevant research in informing policy and practice is of paramount importance. In this regard, initiatives in research capacity strengthening (RCS) are very important. The aim of this study was to review and summarize NCD research capacity strengthening strategies that have been undertaken in LMICs.

Methods

Using both systematic and other literature search, we identified and reviewed NCD-RCS initiatives that have been implemented in LMICs and reported since 2000. Information was extracted from published papers and websites related to these initiatives using a semi-structured checklist. We extracted information on program design, stakeholders involved, and countries of focus, program duration, targeted researchers, disease focus, skill/capacity areas involved and sources of funding. The extracted information was refined through further review and then underwent a textual narrative synthesis.

Results

We identified a number of different strategies used by research capacity strengthening programs and in the majority of initiatives, a combination of approaches was utilized. Capacity strengthening and training approaches were variously adapted locally and tailored to fit with the identified needs of the targeted researchers and health professionals. Most initiatives focused on individual level capacity and not system level capacity, although some undoubtedly benefited the research and health systems of LMICs. For most initiatives, mid-term and long-term outcomes were not evaluated. Though these initiatives might have enhanced research capacity in the immediate term, the sustainability of the results in the long-term remains unknown.

Conclusion

Most of NCD-RCS initiatives in LMICs focused on building individual capacity and only a few focused explicitly on institutional level capacity strengthening. Though many of the initiatives appear to have had promising short-term outcomes, evidence on their long-term impact and sustainability is lacking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Prioritized Research Agenda for the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases (NCDs) identified key areas of research relating to the prevention and control of NCDs [1]. The United Nations Political Declaration on Prevention and Control of NCDs, which has research and development among the major focus areas, recognized the presence of cost-effective interventions for NCD prevention and the numerous opportunities for global action [2]. The Global Action Plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013–2020 included the promotion and support for national capacity for high-quality research for the prevention and control of NCDs as one of its objectives [3]. This action plan called upon international partners to take coordinated action to attain nine voluntary global NCD targets by 2025. The recent Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) also reaffirm the need for research on NCDs that primarily affect low and middle-income countries (LMICS) [4].

In order to achieve these goals, strengthening research capacity in developing countries is critical. Research capacity strengthening (RCS) is a complex concept that can be understood and interpreted in many ways. According to ESSENCE on Health Research, an initiative of funding agencies to improve the coordination and harmonization of research capacity investments, RCS refers to “any efforts to increase the ability of individuals and institutions to undertake high-quality research and to engage with the wider community of stakeholders [5].” Often, RCS is considered as a continuous process both at individual and institutional level and it has been difficult to ascertain the outcomes and define attribution and contribution. It is presumed that successful RCS interventions need to consider individual, institutional and systems components of capacity strengthening [5,6,7,8,9].

The epidemic of NCDs is rapidly emerging in many LMICs. Current evidence shows that 80% of NCD -related deaths occur in LMICs and, more than three quarters of ‘premature’ NCD deaths occur in LMICs [10]. As the magnitude of the epidemic in these countries is expected to increase in the coming years, increasing evidence is being generated on the nature and the scale of this epidemic, the characteristics of the various risk factors, and the social and economic impacts of NCDs [11,12,13].

However, in many LMICs, the national and local level responses to NCDs are based on evidence generated from elsewhere or adapted from that of communicable diseases. Most of the global policy recommendations are based on studies from high income countries or even when data comes from LMICs, studies are led by researchers in high-income countries [14]. Therefore, the role of locally relevant NCD research to inform policy and practice will be of paramount importance in LMICs [1]. In this regard, strengthening the research capacity of local researchers who are best suited to generate locally relevant evidence is critical. However, there is more rhetoric than reality on capacity strengthening of early and mid-career researchers in LMICs [15, 16].

Prior to recent years, the typical model involved research trainees undertaking the majority of their research training in high income countries and that many of these individuals did not return to their own countries on a full-time basis. Some studies have shown that more than half of those trained in developed countries didn’t return to their country though some would still be conducting research in their own country despite living abroad [17, 18]. Accordingly, overseas scholarships/fellowships that encourage trainees to return home or establish collaboration with home institutions are being considered [19].

A limited number of NCD research capacity strengthening initiatives has been implemented in LMICs. Anecdotal evidence suggests that these initiatives are often externally supported and short-lived [20,21,22]. On the other hand, some argue that LMICs do not need stand-alone RCS programs dedicated to NCDs as any RCS on health can also address NCDs. However, RCS initiatives specific to NCDs would be more beneficial to the prevention and control of NCDs than the generic RCS focusing on public health. This is due to the fact that the nature of the NCDs, their responses and their causes and consequences depends on local contexts and there is a strong need to have local capacity to generate contextually relevant research to reduce the evidence-implementation gap [23]. Most of the cost-effective interventions for NCDs need involvement of non-health sectors, are complex in nature and need to follow a life course approach [24, 25]. This assertion is taking into consideration the need for appropriate level of integration, where possible.

To realize global, regional and country level goals in the prevention and control of NCDs, LMICs need better research-based evidence than is currently available. For instance, while implementing and evaluating WHO ‘Best Buys’ is needed most LMICs have not conducted research on these interventions in their populations [26]. To generate and apply such evidence in policy and practice strong research capacity is critical. Therefore, the aim of this review was to review and summarize existing capacity strengthening strategies used by NCD research capacity strengthening initiatives. Additionally, this review investigated the approaches and implementation strategies aimed to improve NCD research capacity in LMICs.

Methods

Study design

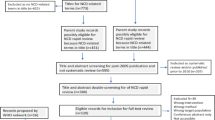

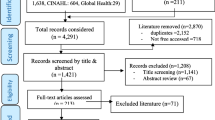

We conducted a systematic review of specific NCD-RCS initiatives that have been implemented in LMICs. This review focused on RCS initiatives that deliberately and systematically addressed NCD research capacity in LMICs. We customized the PRISMA guideline in conducting the review and reporting the findings as the research theme is not a best fit for a typical systematic review.

Study settings

This study has focused on NCD-RCS initiatives in LMICs although the majority of initiatives have been undertaken in collaboration with universities and research institutions from high income countries. The World Bank’s income -based classification (2017) was used for defining LMICs with most being in Africa, Asia, Latin America and Eastern Europe [27] .

Study period

Evidence about NCD-RCS initiatives published between January 1, 2000 and July 31, 2017 were considered in this study. This time horizon was selected because most RCS initiatives commenced after 2000 along following the launching of Global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases [28]. The study included both NCD (generic), disease-specific, and risk-factor specific RCS initiatives.

Search strategy

A systematic literature search with key words (“Non-communicable disease,” “Research Capacity Strengthening/building,” and “Low and Middle-income countries”) combined with a retrospective search from references of papers reporting identified initiatives and a snowballing technique was applied (Table 4 in Appendix 1). We searched Embase, Pubmed and Google scholar for relevant articles. In addition, after identifying an initiative from these and a general search engine, we collected all relevant information relating to that initiative from all possible sources including the initiative’s website, media releases, websites of the funding agencies, and other collaborating institutions for the projects they had funded/implemented. A few NCD researchers from LMIC institutions were also contacted to suggest any remaining initiatives and/or also verify the information about the included initiatives.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Four major inclusion criteria were used to select NCD-RCS initiatives in a progressive manner. These were:

-

1)

Focused primarily on NCDs and/or associated NCD risk factors;

-

2)

Implemented or being implemented in LMICs;

-

3)

Implementation period was between Jan 2000 and July 2017, including ongoing initiatives; and

-

4)

Initiative lasting for a duration of at least 1 year. Initiatives meeting the inclusion criteria and having basic information to describe the model used by the initiative were included.

For bigger NCD-RCS initiatives which had multiple projects, examples of projects that best illustrate the core RCS approach were included.

Extraction of data

A semi-structured check-list (Table 5 in Appendix 3), with the main headings presented in Table 1, was used to extract and collate information obtained from the available sources. The key variables extracted from the information sources include title of the initiative, implementing and collaborating institutions, year of implementation, the disease/risk factor addressed, the targeted researchers/trainees, focus countries, capacity/skills areas addressed, the model/approach/system put in place to implement the initiative and the funding body. While only key information was extracted for most of these variables, more detailed information was extracted for approaches of RCS. TH and AB did the review of initiatives and extraction of information.

Analysis and synthesis of information

A three-stage textual narrative synthesis approach were used [45]. In the first stage, a horizontal description and analysis of each NCD-RCS initiative was conducted. At this stage, we summarized information for each initiative. In the second stage, a vertical analysis and synthesis of information for each parameter and across the initiatives was conducted. We summarized and presented information for each parameter at this stage. In the final stage, a diagonal approach looking across initiatives and parameters as well as how the findings fit with the main principles of RCS was performed. Findings were presented using tables and narrative summaries. An interpretive synthesis approach was used to identify and describe the models.

Results

Description of NCD-RCS initiatives

A total of 14 NCD-RCS initiatives in LMICs that met our inclusion criteria were formally reviewed in this study (see Fig. 1 in Appendix 2). Table 1 presents a detailed description of these initiatives. In brief, most of these initiatives were arranged as a collaboration between developed countries (as sources of funding and as a prime implementing partner) and institutions based in LMICs (as sub-grantee or local partner). US (National Institutes of Health/Fogarty International Centre), Canada (International Research Development Centre) and Australia (National Health and Medical Research Council) based funding bodies and prime partners from those countries were common in these initiatives.

Focus regions and researchers

The NCD-RCS initiatives included in this study covered LMICs in almost in all world regions but with a particular focus on countries in sub-Saharan Africa (7/14), Inter-regional (5/14), South-East Asia and the Pacific region (1/14), Latin America and Caribbean regions (1/14). RCS Collaborations funded by US-based organizations reached most of these regions while those involving Australia-based funding sources were mainly focused on the South-East Asian region. Apart from some of the initiatives that were focused in a single country, most (13/14) were multi-country NCD-RCS initiatives.

The majority (12/14) of the initiatives involved early and mid-career researchers (graduates of Masters Degrees, doctoral students and post-doctoral fellows) as their main target groups for capacity strengthening. A few have also engaged health care professionals – e.g. clinicians, nurses and policy makers - working in the field of NCD prevention and control. However, most of the RCS initiatives lacked an explicit multi-sectoral focus and typically, were more focused on the health sector.

NCDs and risk factors of interest

Most (9/14) NCD-RCS initiatives were generic and thus not limited to any specific non-communicable or chronic diseases or risk factor and considered all forms of NCDs. Some (2/14) have areas of concentration on specific clusters or combinations of diseases such as cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, heart and lung diseases, diabetes or cancers. Nevertheless, a few (3/14) were also limited to specific disease (cancer) or risk factor (tobacco use). Accordingly, the NCD-RCS initiatives were categorized as generic, concentrated, and specific.

Implementation mechanism

All of the NCD-RCS initiatives involved collaboration among a number of institutional and other partners from other countries and regions to deliver the program. While North-South Collaboration was the most common, there are also more recent examples of North-South-South collaboration and South-South collaborations. As described in Table 1, six out of the 14 initiatives have been completed, while the remaining eight are long-term and ongoing.

Strategies of RCS

Based on the review of the included NCD-RCS initiatives, we have identified a number of inter-related strategies for capacity strengthening. Many of the initiatives are a hybrid of more than one of these. We summarized these models in Table 2 below. Examples of the models of NCD-RCS initiatives and their brief descriptions are provided in Table 3.

Capacity areas addressed

While most of these approaches or strategies focused on building individual and team level NCD research capacity, less than half of the initiatives have also claimed institutional-level capacity building. A limited number (4/14) have included efforts to strengthen capacity at the research network level, as well. However, only one initiative had addressed research capacity at all levels.

Strengthening capacity in conducting research was the focus of the reviewed NCD-RCS initiatives. Engagement with potential users of research to promote use of evidence has received less attention. Research capacity in increasing the breadth (involving multiple countries) and depth of understanding of NCD epidemic was underpinning most of the NCD-RCS approaches.

Almost all the NCD-RCS focused on enhancing research or research engagement capacity with little direct action on NCD management skills. The research skill areas addressed are generic. But for some of the initiatives it was on specific NCD research as the funding streams were specific to a disease or a risk factor.

Discussion

Summary of the findings

This study has identified that many new and hybrid models of NCD-RCS are emerging in low and middle-income countries in recent years, especially in sub-Saharan Africa and Asian countries. With the increasing priority being accorded to NCD prevention and control in these settings in terms of policy and resource allocations [46], this is a positive development that has the potential to contribute to a narrowing of the evidence-implementation gap, thereby contributing to the realization of the global NCD targets.

Interpretation of the findings

Multi-faceted strategies of NCD training and capacity strengthening are becoming more common within countries and there is less reliance on long periods of overseas training. The most common strategies included face-to-face sessions, online training and learning by undertaking research. Internet and new technologies are being utilized more overtly in program delivery over time. Recent initiatives are considering the use of internet and new technologies; the collaboration between institutions in LMICs and high-income countries; and involvement of the diaspora in reducing ‘brain drain’ which was a problem in traditional overseas scholarships and fellowships. Some initiatives also provided some financial support for undertaking research.

Although we have provided a brief description of the common approaches used in NCD-RCS, it was not possible to identify which model was or could be more/less effective than the other in terms of improving research performance and quality of research outputs. This was due to the fact that evidence on outcomes of these initiatives was not readily available. Evaluation of outcomes of RCS programs is complex and even if evaluations are conducted they can only demonstrate short-term and immediate outcomes [8, 47]. In this regard, future NCD-RCS initiatives need to integrate evaluation studies that can demonstrate long-term outcomes of such initiatives.

On the other hand, there is little evidence to ascertain the continuity and sustainability of the results of these initiatives. Tracing the outputs of the trainees after completion of the program was not part of most of the initiatives and evidence on continuing engagement of the trainees in research is lacking. One plausible reason for this could be the nature of funding of the initiatives. As shown in this study, most of the NCD-RCS initiatives were funded by external donors. This can affect the sustainability of the initiatives as local systems may not continue implementing the initiatives after the funding is withdrawn [48]. Moreover, country ownership of the initiatives can only be ensured with full participation of the local systems in the design, implementation and evaluation of these initiatives [49].

Implications of the findings

The models/approaches used by NCD-RCS initiatives share many similarities with that of RCS in other health areas like communicable diseases. As the generic research skills required for NCDs and chronic communicable diseases overlap, the NCD-RCS initiatives can learn from evidence on RCS in chronic infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis [50]. Not only the lesson, but also researchers trained in chronic infectious disease research, through a tailored research mentoring program, could be motivated to engage in NCD research in LMICs. This would be of significant importance in research on co-morbidities between communicable and NCDs.

Most of the NCD-RCS initiatives have focused on strengthening individual level capacity. However, very little has been done to improve institutional and system level capacity. Without a meaningful change in institutional research infrastructure and system level research culture, it will be challenging to improve performance of researchers, quality of research outputs and more importantly the utilization of research findings for policy and action [51]. Therefore, a more comprehensive and integrated approach to NCD-RCS is needed in LMICs.

We observed a modest increase in the number of NCD-RCS initiatives in LMICs across years [21]. However, whether NCD research training programmes are closely linked with the national NCD prevention and control agenda in LMICs is not well examined and the establishing locally relevant and harmonized NCD research capacity strengthening agenda is the main priority in the foreseeable future. Given the significant gap between research evidence and public health priorities LMICs, formulating NCD RCS agenda would also help bridge this gap between NCD research and implementation of NCD programs [52].

Limitations of the study

This study used multiple sources of information and applied a deeper analysis of information to identify and describe NCD-RCS models. However, there were some limitations associated with this review. Firstly, this review largely used publicly available evidence as its main source of information. Consequently, our resulting models may not include all the available ones. Secondly, in this review, we used a mix of peer-reviewed literature and grey literature to identify and describe the approaches and we did not undertake any quality assessment of the evidence. Thirdly, the initiatives included in this study vary from single projects to networks and bigger funding schemes. There are several smaller projects within the bigger funding schemes that have various focus areas. These were represented by the overall model/approach at scheme level. Fourthly, with the inclusion criteria of programs at least one year in length, it is likely to have missed many but important initiatives with shorter duration. Furthermore, since a lot of the research capacity building activities are not published in peer-reviewed journals, it is likely to have missed several important ones. Finally, there was a lack of information in the data sources of the selected NCD-RCS initiatives as the study highly relied on secondary information.

Conclusions and recommendations

In this study, we identified and described several different approaches of NCD-RCS as applied by the initiatives included in the review. Diverse and hybridized approaches of NCD-RCS initiatives have been implemented in many LMICs. However, information on program design, implementation and evaluation of these initiatives is inadequate. Consequently, the relative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of these initiatives remain largely unknown. Moreover, given the external funding of these initiatives, the sustainability of the NCD-RCS initiatives at local level remains a critical concern. Proper documentation and evaluation of NCD-RCS initiatives would enhance the outcomes and implementation of NCD-RCS initiatives.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AACR-AORTC:

-

American Association for Cancer Research and African Organisation for Research and Training in Cancer (AACR - AORTIC)

- AIIMS:

-

All India Institute of Medical Science

- ANPPA:

-

Analysis of Non-communicable Diseases Prevention Policies in Africa

- APCDR:

-

African Partnership for Chronic Disease Research

- APHRC:

-

African Population and Health Research Center

- ASCEND:

-

ASian Collaboration for Excellence in Non-Communicable Disease

- CCCC:

-

Centre for the Control of Chronic Conditions

- CDC:

-

Center for Disease Control

- CNCD:

-

Consortium for Non-Communicable Disease

- ENCORE:

-

Excellence in NonCOmmunicable disease Research

- FIC:

-

Fogarty International Center

- GACD:

-

The Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases

- HHS:

-

Health and Human Services

- IDRC:

-

International Development Research Centre

- INDEPTH:

-

International Network for the Demographic Evaluation of Populations and their Health

- IUPHE:

-

International Union for Health Promotion and Education

- KSN-NCD:

-

Knowledge Sharing Network on Non-communicable Diseases

- MRC:

-

Medical Research Council, UK

- NHLBI:

-

National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute

- NIDA:

-

National Institute on Drug Abuse

- NIH:

-

National institute of Health

- PHFI:

-

Public Health Foundation India

- RLTP:

-

Research Leadership Training Program

- RTI:

-

Research Triangle Initiative

- SCTIMST:

-

Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology

- TOBAC:

-

International Tobacco and Health Research and Capacity Building Program

- YP-CDN:

-

Young Professional Chronic Disease Network

References

Mendis S, Alwan A, editors. Prioritized research agenda for prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

United Nations. Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the general assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseasesUN; 2011.

World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. Geneva: WHO; 2013.

United Nations. Sustainable development goals (SDGs): United Nations; 2016. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/sustainabledevelopmentgoals

ESSENCE on Health Research. Seven principles for strengthening research capacity in low- and middle-income countries: simple ideas in a complex world. ESSENCE: Geneva; 2014.

ESSENCE on Health Research. Planning, monitoring and evaluation framework for research capacity strengthening. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2016.

Bates I, Boyd A, Aslanyan G, Cole DC. Tackling the tensions in evaluating capacity strengthening for health research in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(3):334–44.

Boyd A, Cole DC, Cho DB, Aslanyan G, Bates I. Frameworks for evaluating health research capacity strengthening: a qualitative study. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:46.

Cole DC, Boyd A, Aslanyan G, Bates I. Indicators for tracking programmes to strengthen health research capacity in lower- and middle-income countries: a qualitative synthesis. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12:17.

Smeeth L, Ebrahim S. Non-communicable diseases in low and middle-income countries: a priority or a distraction? Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(5):961–6.

Ebrahim S, Pearce N, Smeeth L, Casas JP, Jaffar S, Piot P. Tackling non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: is the evidence from high-income countries all we need? PLoS Med. 2013;10(1):e1001377.

Boutayeb A, Boutayeb S. The burden of non communicable diseases in developing countries. Int J Equity Health. 2005;4(1):2.

Islam SM, Purnat TD, Phuong NT, Mwingira U, Schacht K, Froschl G. Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in developing countries: a symposium report. Glob Health. 2014;10:81.

World Health Organization. ‘Best buys’ and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: updated (2017) appendix 3 of the global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020; 2017.

Checkley W, Ghannem H, Irazola V, Kimaiyo S, Levitt NS, Miranda JJ, et al. Management of NCD in low- and middle-income countries. Glob Heart. 2014;9(4):431–43.

Miranda JJ, Kinra S, Casas JP, Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. Non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: context, determinants and health policy. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(10):1225–34.

Dodani S, LaPorte RE. Brain drain from developing countries: how can brain drain be converted into wisdom gain? J R Soc Med. 2005;98(11):487–91.

Binanay CA, Akwanalo CO, Aruasa W, Barasa FA, Corey GR, Crowe S, et al. Building sustainable capacity for cardiovascular Care at a Public Hospital in Western Kenya. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(22):2550–60.

Wiesel T. Fellowships: turning brain drain into brain circulation. Nature. 2014;510(7504):213–4.

Kilic B, Phillimore P, Islek D, Oztoprak D, Korkmaz E, Abu-Rmeileh N, et al. Research capacity and training needs for non-communicable diseases in the public health arena in Turkey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:373.

Sturke R, Vorkoper S, Duncan K, Levintova M, Parascondola M. Addressing NCDs through research and capacity building in LMICs: lessons learned from tobacco control. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:32407.

Shilton T, Champagne B, Blanchard C, Ibarra L, Kasesmup V. Towards a global framework for capacity building for non-communicable disease advocacy in low- and middle-income countries. Glob Health Promot. 2013;20(4 Suppl):6–19.

World Health Organization. A guide to implementation research in the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2016.

Baird J, Jacob C, Barker M, Fall CH, Hanson M, Harvey NC, et al. Developmental origins of health and disease: a Lifecourse approach to the prevention of non-communicable diseases. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2017;5(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5010014.

Alwan AD, Galea G, Stuckler D. Development at risk: addressing noncommunicable diseases at the United Nations high-level meeting. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(8):546-a.

Allen LN, Pullar J, Wickramasinghe KK, Williams J, Roberts N, Mikkelsen B, et al. Evaluation of research on interventions aligned to WHO ‘best buys’ for NCDs in low-income and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review from 1990 to 2015. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(1):e000535.

World Bank. World bank list of economies Jun 2017: World bank; 2017. Available at https://libraries.acm.org/binaries/content/assets/libraries/archive/world-bank-list-of-economies.pdf, retrived April 2018.

World Health Orgnaization. Global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable disease. Geneva: WHO; 2000.

Fogarty International Center. International tobacco and health research and capacity building program review. Washington, DC: FIC; 2013.

Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases. Research network: GACD; 2017. Available from: http://www.gacd.org/research/research-network

Amuyunzu-Nyamongo M, Owuor JO, Blanchard C. The consortium for NCD prevention and control in sub-Saharan Africa (CNCD-Africa): from concept to practice. Glob Health Promot. 2013;20(4 Suppl):97–103.

Chu KM, Jayaraman S, Kyamanywa P, Ntakiyiruta G. Building research capacity in Africa: equity and global health collaborations. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3):e1001612.

RTI International. NextGen leaders program: building capacity and establishing leadership for noncommunicable disease advocacy in East Africa: RTI; 2016. Available from: https://www.rti.org/impact/nextgen-leaders-program

Bloomfield GS, Xavier D, Belis D, Alam D, Davis P, Dorairaj P, et al. Training and capacity building in LMIC for research in heart and lung diseases: the NHLBI-UnitedHealth Global Health centers of excellence program. Glob Heart. 2016;11(1):17–25.

Fogarty International Center. Chronic, noncommunicable diseases and disorders research training (NCD-lifespan): FIC; 2017. Available at https://www.fic.nih.gov/Programs/Pages/chronic-lifespan.aspx, retrived April 2018

Oldenburg B, Wickramasinghe K, Byrnes A. Building noncommunicable disease research capacity in the south Asian region:the ASCEND program. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2016;28(1_suppl):6S–9S.

APCDR. The African Partnership for Chronic Disease ResearchAPCDR; 2010.

Arnold LD, Barnoya J, Gharzouzi EN, Benson P, Colditz GA. A training programme to build cancer research capacity in low- and middle-income countries: findings from Guatemala. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(4):297–302.

Ramsay M, Sankoh O. African partnerships through the H3Africa consortium bring a genomic dimension to longitudinal population studies on the continent. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(2):305–8.

Juma PA, Mohamed SF, Wisdom J, Kyobutungi C, Oti S. Analysis of non-communicable disease prevention policies in five sub-Saharan African countries: study protocol. Arch Public Health. 2016;74:25.

African Population and Health Research Center. Kenya NCD info knowledge sharing web-portal. Naiorbi: APHRC; 2013.

Mohammed SI, Williams CK, Ndom P, Holland JF. The African Organization for Research and Training in cancer: historical perspective. Curr Oncol (Toronto, Ont). 2012;19(5):272–6.

University of Melbourne. ENCORE program: excellence in NonCOmmunicable disease research between Australia and India. Melbourne: School of Populaiton and Global Health; 2016.

NCD Alliance. East African NCDA initiates continent-wide NCD research group; 2017. Available from: https://ncdalliance.org/news-events/news/east-african-ncda-initiates-continent-wide-ncd-research-group-0

Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:59.

Maher D, Ford N, Unwin N. Priorities for developing countries in the global response to non-communicable diseases. Glob Health. 2012;8:14.

Minja H, Nsanzabana C, Maure C, Hoffmann A, Rumisha S, Ogundahunsi O, et al. Impact of health research capacity strengthening in low- and middle-income countries: the case of WHO/TDR programmes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(10):e1351.

Gadsby EW. Research capacity strengthening: donor approaches to improving and assessing its impact in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2011;26(1):89–106.

Hyder AA, Rattani A, Pratt B. Research capacity strengthening in low- and middle-income countries: ethical explorations. J Law, Med Ethics J Am Soc Law, Med Ethics. 2017;45(1):129–37.

Kaser M, Maure C, Halpaap BM, Vahedi M, Yamaka S, Launois P, et al. Research capacity strengthening in low and middle income countries - an evaluation of the WHO/TDR career development fellowship Programme. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(5):e0004631.

Vasquez EE, Hirsch JS, Giangle M, Parker RG. Rethinking health research capacity strengthening. Glob Public Health. 2013;8(Suppl 1):S104–24.

Goyet S, Touch S, Ir P, SamAn S, Fassier T, Frutos R, et al. Gaps between research and public health priorities in low income countries: evidence from a systematic literature review focused on Cambodia. Implement Sci. 2015;10:32.

Acknowledgements

This study was initiated along with of the ASCEND which was funded by the FIC of the NIH under Award Number: D43TW008332. We extend our thanks to the WHO Collaborating Centre for NCD Implementation Research at the University of Melbourne for supporting this study. We also thank Kate Chalmers and Ameera Katar for their critical review of the draft manuscript. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding

This study was initiated along with Asian Collaboration for Excellence in Non-Communicable Disease (ASCEND) study which was funded by the Fogarty International Centre (FIC) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number: D43TW008332.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TH, AB, NP and BO conceptualized the study, conducted the search and review of the literature and drafted the manuscript. KS, TS, KW, KRT and GP provided substantial input into the draft manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Haregu, T.N., Byrnes, A., Singh, K. et al. A scoping review of non-communicable disease research capacity strengthening initiatives in low and middle-income countries. glob health res policy 4, 31 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-019-0123-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-019-0123-1