Abstract

Host response to the human immune deficiency virus (HIV) involves both the innate and adaptive immune systems. As part of the innate immune system, the killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) found on natural killer cells and some T-lymphocytes are genetically diverse and play key functions in the host response against viral pathogens. In the last decade, there has been substantial growth in sequencing technologies and bioinformatics capacity to understand human host genetics, including KIR. However, there is limited literature on how the KIR diversity informs the perspectives on HIV disease states in understudied African settings. A better understanding of the effects of KIRs on the host’s immune response to HIV in African settings is essential to inform strategies to develop more effective therapies and vaccines to improve health among people living with HIV (PLWH). In this paper, we review KIR diversity, the role of KIR immunogenetic variation in the human host response to HIV, discuss current perspectives on the studies to assess the relationship between KIR diversity and the HIV disease continuum, and suggest future research prospects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human immune deficiency virus (HIV) infection remains a major global public health problem with approximately 38 million people affected and the highest numbers of affected individuals found in Eastern and Southern Africa [1]. This is despite the reductions in morbidity and mortality due to HIV with the introduction and increased availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH). Among PLWH, there are differences in the adaptive and innate immune responses because of their underlying host genetic makeup, viral and environmental factors [2]. The adaptive immune system provides long-term protection to the human host while the innate immune system serves as the first line of defense against pathogens that enter the body. In the innate immune response to HIV infection, natural killer (NK) cells have been demonstrated to modify and direct the human host’s reaction to disease [3].

NK cells constitute a sub-population of lymphocyte-related cells that recognize pathogen-infected cells and perform immune-regulatory functions in response to viral infections through the production of cytokines like interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and macrophage inflammatory proteins (MIP-1α /CCL3 and CCL4/MIP-1β), which recruit various inflammatory cells into sites of inflammation [4, 5]. In addition, NK cells have surface-based receptors that modulate activating and inhibitory NK cell functions during the human host's response to cancers and infections like HIV. Among these receptors are CD16, NKG2D, cytotoxic receptors (NKp46), CD337 (NKp30), CD226 (DNAM-1), and members of the killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) family [6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

KIRs bind specific HLA ligands, which are encoded in the human region of chromosome 6q21.3 to modulate response to disease among the NK cell family. For example, KIR3DL1 interacts with HLA-Bw4 [13] while KIR2DL2, KIR2DS2 and KIR2DL3 receptors bind HLA-C1 epitopes [14]. KIR2DL1, KIR2DS1, and KIR2DL2 receptors recognize HLA-C2 molecules with lysine at position 80 while KIR3DS1 recognizes the open conformation of HLA-F [15]. KIR3DL2 receptors interact with HLA A11 ligands [16]. Additionally, genetic studies have identified associations between the presence of KIR genes with their human leukocyte antigen (HLA) ligands in the context of HIV disease states [17,18,19] although knowledge gaps remain on the relevance of these associations in genetically diverse African populations.

Here, we present an overview of KIR immunogenetics in the context of their role in the human host’s response to HIV infection and propose future KIR-HIV research directions, with a focus on African populations.

KIR overview

KIRs are glycoprotein in nature, highly polymorphic and are encoded by genes located in a ~ 160–200 kilobase (kb) region of the leukocyte receptor complex (LRC) on the human chromosome 19q13.4 region [9, 13, 20, 21], which is one of the most rapidly evolving regions of the human genome [22].

KIR genes are named based on their structural and functional characteristics [23]. The KIR gene name consists of information on both extracellular immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains (designated as “D”), which group the KIRs into categories based on the presence of two or three of these domains, for example, KIR2D or KIR3D; and cytoplasmic domains (named as either “L” for long or “S” for short) [9]. This structural difference based on domains also confers functional divergence in that KIRs with “S” domains are mainly activating to NK cells while those with “L” domains are inhibitory in nature. The final digit of the KIR gene name (like KIR3DL3) indicates the number of genes encoding a protein with this structure [24].

Classically, the KIR complex consists of 13 protein-coding genes (2DL1, 2DL2/L3, 2DL4, 2DL5A, 2DL5B, 2DS1, 2DS2, 2DS3, 2DS4, 2DS5, 3DL1/S1, 3DL2 and 3DL3), and 2 pseudogenes (2DP1, 3DP1). The variability in the presence of these genes on the different haplotypes contributes to the KIR repertoire diversity in NK cells [9]. This has been attributed to intensive non-allelic homologous recombination and gene duplication events [25]. Likewise, selective pressure from pathogens and human reproductive success leading to a balanced selection of KIR haplotypes also affects the evolutionary divergence of KIR genes [25]. KIR haplotypes are commonly organized according to two general structures, “A” and “B,” depending on the arrangement of genes on each haplotype. “Framework genes,” which include KIR2DL4, KIR3DL2, KIR3DL3 and KIR3DP1, are present in both haplotypes (Fig. 1).

Arrangement of KIR genes on the KIR haplotypes A and B as adapted from previous research [9]. Framework genes are common in both haplotypes A and B. KIR2DL4 performs both inhibitory and activating functions

KIR haplotype A is defined by the presence of KIR2DL3, KIR2DL1, KIR3DL1, KIR2DP1, and KIR2DS4 and framework genes (Table 1). It has mainly inhibitory loci and has generally been observed in close to half of the individuals in most populations studied worldwide [26, 27]. Of note, haplotype A has KIR2DS4 as the only activating gene and in some cases, there may be a complete absence of any activating gene due to the existence of a 22 base pair deletion in exon 5 in the transmembrane domain of the common null 2DS4 allele [28]. In contrast, KIR haplotype B is defined by the presence of variable combinations of activating and inhibitory genes and alleles [25, 29]. Recombination hotspots are located at the centrometric (Cen) and telomeric (Tel) ends of each of the haplotypes with the major hotspot at the Cen –Tel Junction [30]. Crossover at these hotspots leads to the formation of hybrid haplotypes like CenA-TelB or CenB-TelA which are conventionally classified under haplotype B [31].

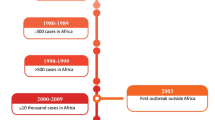

On the African continent, researchers have explored the diversity of the KIR region, but the number of studies remains limited (Fig. 2) compared to the population density (Supplementary table, S1) and genetic diversity of the continent. The diversity of the KIRs has been explored at both the gene content and allelic diversity levels (Table 2). For example, in a gene content study among 492 healthy female individuals from Uganda, East Africa, the frequencies of KIR telomeric B region genes KIR3DS1 and KIR2DS1 were significantly less than those in a UK database [32]. Another study focused on both gene content and allelic diversity discovered that the Ga-Adangbe people from Ghana had a high diversity of KIR alleles encoding HLA-C ligand receptors and low diversity of genes in the KIR telomeric region encoding Bw4 specific –KIR3DL1 genes [33]. In this study, a KIR3DL1/KIR3DL2 fusion gene was uncovered and found unique in African populations in comparison with other non-African populations. Additionally, 10% of the Ga-Adangbe KIR haplotypes identified in this study were missing one of the three framework genes, which was a high prevalence. Likewise, new variants of KIR2DL1 that change HLA-C ligand specificity, and new haplotype variations of KIR3DL2 and KIR2DL4 were identified together with common duplications of the KIR3DL1 and KIR2DL4 [33]. At the allelic level, the 208 allele-level haplotypes from 19 gene content KIR haplotypes were recognized among the Ga-Adangbe population [33]. Approximately 95% of these alleles encoded different combinations of KIR proteins and functional characteristics. Although there was high allele diversity in this population, the frequency of the haplotypes remained below 10% [33]. Our previous work involving African, Middle Eastern, East and Central Asian, European, American and Ocean populations from the Human Genome Diversity Project—Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (HGDP-CEPH) panel also found high gene content diversity among the Africans [27]. The San, Papuan and Mbuti African populations had few or no individuals with any of the top six genotypes identified in other populations in the panel. It is also interesting to note that the three African hunter-gatherer populations (San, Biaka and Mbuti pygmies) in the HGDP-CEPH panel showed high overall KIR B haplotype frequencies except for KIR2DS1, KIR2DS3, and KIR3DS1 [27]. Another KIR gene content study was performed in Cote D’Ivoire where they found significantly higher frequencies of the KIR2DL2 and KIR2DL5 genes when comparing the HIV-exposed seronegative and HIV-positive female sex workers [34].

Another study involving African populations identified significant differences in allele frequencies of KIR variants between the Baka and Fulani from West Africa, Mbuti from central Africa, and Datooga, Iraqw and Hadza from Tanzania in East Africa [44]. In that study, 28 new KIR alleles that were each specific to one of the seven populations from Sub-Saharan Africa were identified. The Baka, which is a pygmy population had the highest number of KIR alleles (16 alleles); an illustration of how divergent they were from their common ancestors when compared to other populations [44].

Based on these studies, it is clear that African populations have unique KIR variation and complexity and it is likely that additional KIR gene content and allele level genetic variation can be discovered if large population studies from all regions of Africa are conducted. We anticipate that KIR diversity on the African continent will continue to prove extensive, as previous studies have demonstrated that Africa has high human genomic diversity relative to other continents [42].

KIR Immunogenetic variation and relevance to immunity in HIV among African populations

KIR associations with HIV disease states

Several studies have supported the existence of a relationship between KIR variation and immunity to HIV, which we discuss here in the context of infection acquisition and progression stages among PLWH. A study among 183 treatment-naive HIV-infected adults of Bantu origin from Zimbabwe found the KIR2DL3 gene associated with markers of chronic immune activation in HIV as measured by plasma concentrations of interferon-γ-induced protein 10 (IP-10) as a proxy for NK cell response to HIV infection (Table 3) [41]. However, the application of the findings from this paper is limited by the small sample size, the use of samples from only southern Africa and the fact the IP-10 concentrations are non-specific for HIV disease [43, 45]. In another study, among 145 HIV-1 infected patients and 134 HIV-negative individuals, KIR3DL1 was associated with protective effects against HIV infection among adults in Burkina Faso [37]. A possible explanation for the protective KIR effects may be through increased NK cell activation and clonal expansion leading to stronger antiviral effects on HIV-infected cells [46]. In contrast, a study conducted in Tanzania found that KIR3DS1 in combination with HLA-Bw4-80Ile was significantly associated with an increased risk of HIV infection [47]. Another study, evaluating HIV-positive women in South Africa found no association between KIR genes and HIV acquisition [39].

Using linear mixed models, the presence of KIR haplotype BB has been associated with lower HIV viral load copies among HIV infected women at cross-sectional analysis [39]. Although, there are no studies that have replicated this finding, it is worth exploring in future research and clinical studies as more next generation sequencing data becomes available.

In terms of HIV disease progression, the KIR3DL1/S1 genes have been associated with slow disease progression among African-Americans and European American PLWH although studies from Africa are lacking [18, 19, 48, 51]. Given the above evidence, it is difficult to draw consistent conclusions on KIR associations and HIV disease states across the different populations. On the other hand, inconsistencies in previous research findings may point to the possibility that novel KIR associations may be uncovered if more systematic KIR studies in HIV populations are performed on the diverse African continent.

Effect of ART on KIR functionality among PLWH

Globally, almost all countries currently implement the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation of treating all individuals with ART who test positive for HIV infection irrespective of CD4 T-cell count or age [52], with the effect of exposing individuals to ART for a long time. ART does not eliminate the virus but acts by reducing HIV viral load and delaying both the progression to AIDS and HIV–related immune activation, which would otherwise lead to immune dysregulation and T-cell dysfunction [53, 54].

There have been few studies globally on the effects of exposure to ART and the functionality of NK cells and their KIRs [55]. A study evaluating the phenotypic and functional characteristics of NK cells found that ART-naïve American patients with HIV viremia had significantly reduced CD56dim/CD16+ subsets of NK cells as compared to the healthy donors [56]. In the same study, those HIV+ individuals with below detectable viremia after ART for two years had a more conservative expression of KIR2DL2, KIR2DL1 and KIR3DL1 genes than high viremia patients [56]. However, this study had a small sample size of 46 participants, was performed in non-African settings and did not explore all KIR genes, limiting its transferability to African settings and populations. By contrast, there are no studies that have evaluated the KIRs among PLWH in Africa that have had prolonged exposure (at least ten years) to ART. There are also no studies that have evaluated the association between specific KIR haplotypes and HIV treatment response outcomes. Clinically, an understanding of the functionality of KIRs in the context of the presence or absence of ART may enhance our knowledge of the HIV disease trajectories and immunological determinants of outcomes of treatment.

Prospects for KIR-HIV research in African settings

The Human Heredity and Health in Africa (H3Africa) consortium initiative was established with funding partnerships from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Wellcome Trust to spearhead innovative community-oriented research into the genetic and environmental basis for human diseases of relevance to Africans as well as to build capacity for genomic research on the continent [57]. In its first and second phases of funding, the H3Africa network of researchers focused on the understanding of the complex genetics of Africans and the advancement of genomic technologies uptake across the African continent in the race towards the application of genomic findings into clinical care. As a result, the leveraging of the collected samples and genomic findings across this consortium from African populations [58,59,60,61] may offer new prospects about the gateways into the understanding of human disease pathways, especially in genetically complex regions in the human genome like the KIR region. In the same way, the continued engagement of the breadth of the established expertise, collaborations and newly trained genomic researchers in tandem with the increased bioinformatics capacity in Africa by the H3Africa consortium and its post-funding re-organizations offers a great opportunity for the advancement of KIR-HIV research in Africa.

Furthermore, future studies on KIR diversity and the KIR-HIV relationship on the African continent may benefit from the use of the emerging genomic technologies and bioinformatics tools like Pushing Immunogenetics to Next-Generation bioinformatics pipeline [62, 63], Oxford Nanopore technologies [64, 65] and Pacific Biosciences [66] to close four key knowledge gaps. Firstly, the nature of KIR diversity in underrepresented geographic regions within Africa. Secondly, research in the identification of epigenetic mechanisms that determine KIR functional diversity among PLWH exposed to varying environmental and pathogen stresses, ageing with HIV, living with comorbidities of non-communicable diseases and HIV/ AIDS-related complications.

Thirdly, the spectrum of KIR associations with clinical outcomes in both infectious and non-communicable diseases among Africans; and fourthly, the creation of geographically representative scaffolds for the determination of KIR genotypes and haplotypes to support short-read and long-read sequencing technologies. The closure of these knowledge gaps may inform translational researchers to design actionable vaccines and therapeutic targets that may help improve the lives of PLWH.

Concluding remarks

KIRs remain genetically diverse at both the gene content and allelic levels across human populations leading to altered NK cell immune activity even in HIV infection. KIR genes like KIR2DL5 and KIR3DL1/S1 are associated with HIV disease acquisition and progression to AIDS phenotypes among population studies from Africa and other continents. However, our current knowledge of KIR diversity in Africa remains limited in comparison to the size, population density, and genetic diversity of the continent. A pertinent understanding of the KIR genotype and haplotype diversity relevant to HIV disease phenotypes in African populations would undoubtedly inform advances in our understanding of the host’s innate immune responses in HIV infection and vaccine design studies. Similarly, a further utilization of the available and novel techniques in bioinformatics and KIR genetics research technologies is required to fill knowledge gaps and guide future research in HIV populations especially in Africa, which has a disproportionate burden of HIV and other infectious diseases.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

UNAIDS. UNAIDS data. 2021.

Mohan T, Bhatnagar S, Gupta DL, Rao DN. Current understanding of HIV-1 and T-cell adaptive immunity: progress to date. Microb Pathog. 2014;73:60–9.

Janeway Jr CTP, Walport M. Immunobiology: The immune system in health and disease. In: Principles of innate and adaptive immunity. New York: Garland Science;: 2001. New York: Garland Science; 2001. Prnity. Report No.

Maghazachi AA. Role of Chemokines in the Biology of Natural Killer Cells. In: Bruserud O, editor. The Chemokine System in Experimental and Clinical Hematology. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg; 2010. p. 37–58.

Diefenbach A, Steinle A. Natural killer (NK) cells: an important role in the immune system’s defense against viral infections. Introduction. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68(21):3453–5.

Li H, Pascal V, Martin MP, Carrington M, Anderson SK. Genetic control of variegated KIR gene expression: polymorphisms of the bi-directional KIR3DL1 promoter are associated with distinct frequencies of gene expression. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(11):e1000254.

Schleinitz N, Hamidou M, Vély F, Paul P, Figarella-Branger D, Kaplanski G, et al. NK cells: new insights on physiology and clinical implication in diseases. La Revue de medecine interne. 2005;27(6):465–72.

Ashouri E, Farjadian S, Reed EF, Ghaderi A, Rajalingam R. KIR gene content diversity in four Iranian populations. Immunogenetics. 2009;61(7):483–92.

Carrington M, Norman P. The KIR gene Cluster. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2003.

Gwozdowicz S, Nestorowicz K, Graczyk-Pol E, Szlendak U, Rogatko-Koros M, Mika-Witkowska R, et al. KIR specificity and avidity of standard and unusual C1, C2, Bw4, Bw6 and A3/11 amino acid motifs at entire HLA: KIR interface between NK and target cells, the functional and evolutionary classification of HLA class I molecules. Int J Immunogenet. 2019;46(4):217–31.

Moretta A, Marcenaro E, Parolini S, Ferlazzo G, Moretta L. NK cells at the interface between innate and adaptive immunity. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(2):226–33.

Bartel Y, Bauer B, Steinle A. Modulation of NK cell function by genetically coupled C-type lectin-like receptor/ligand pairs encoded in the human natural killer gene complex. Front Immunol. 2013;4:362.

Khakoo SI, Rajalingam R, Shum BP, Weidenbach K, Flodin L, Muir DG, et al. Rapid evolution of NK cell receptor systems demonstrated by comparison of chimpanzees and humans. Immunity. 2000;12(6):687–98.

Hirayasu K, Ohashi J, Kashiwase K, Hananantachai H, Naka I, Ogawa A, et al. Significant association of KIR2DL3-HLA-C1 combination with cerebral malaria and implications for co-evolution of KIR and HLA. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(3):e1002565.

Garcia-Beltran WF, Hölzemer A, Martrus G, Chung AW, Pacheco Y, Simoneau CR, et al. Open conformers of HLA-F are high-affinity ligands of the activating NK-cell receptor KIR3DS1. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(9):1067–74.

Boudreau JE, Hsu KC. Natural killer cell education in human health and disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 2018;50:102–11.

Luc-Aimé KS, Louis-Marie Y, Gabriel LE, Yengo CK. Killer-Cell Immunoglobulin-Like Receptors (KIR) in HIV-Exposed Infants in Cameroon. J Immunol Res. 2021;2021:9053280.

Malnati MS, Ugolotti E, Monti MC, De Battista D, Vanni I, Bordo D, et al. Activating killer immunoglobulin receptors and HLA-C: a successful combination providing HIV-1 control. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42470.

Jiang Y, Chen O, Cui C, Zhao B, Han X, Zhang Z, et al. KIR3DS1/L1 and HLA-Bw4-80I are associated with HIV disease progression among HIV typical progressors and long-term nonprogressors. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):405.

Wilson MJ, Torkar M, Haude A, Milne S, Jones T, Sheer D, et al. Plasticity in the organization and sequences of human KIR/ILT gene families. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97(9):4778–83.

Vilches C, Parham P. KIR: diverse, rapidly evolving receptors of innate and adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20(1):217–51.

Augusto DG, Norman PJ, Dandekar R, Hollenbach JA. Fluctuating and Geographically Specific Selection Characterize Rapid Evolution of the Human KIR Region. Front Immunol. 2019;10:989.

Campbell KS, Purdy AK. Structure/function of human killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors: lessons from polymorphisms, evolution, crystal structures and mutations. Immunology. 2011;132(3):315–25.

Middleton D, Gonzelez F. The extensive polymorphism of KIR genes. Immunology. 2010;129(1):8–19.

Parham P, Moffett A. Variable NK cell receptors and their MHC class I ligands in immunity, reproduction and human evolution. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(2):133–44.

Colucci F, Traherne J. Killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors on the cusp of modern immunogenetics. Immunology. 2017;152(4):556–61.

Hollenbach JA, Nocedal I, Ladner MB, Single RM, Trachtenberg EA. Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) gene content variation in the HGDP-CEPH populations. Immunogenetics. 2012;64(10):719–37.

Maxwell LD, Wallace A, Middleton D, Curran MD. A common KIR2DS4 deletion variant in the human that predicts a soluble KIR molecule analogous to the KIR1D molecule observed in the rhesus monkey. Tissue Antigens. 2002;60(3):254–8.

Marsh SG, Parham P, Dupont B, Geraghty DE, Trowsdale J, Middleton D, et al. Killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) nomenclature report, 2002. Tissue Antigens. 2003;62(1):79–86.

Pyo C-W, Guethlein LA, Vu Q, Wang R, Abi-Rached L, Norman PJ, et al. Different patterns of evolution in the centromeric and telomeric regions of group A and B haplotypes of the human killer cell Ig-like receptor locus. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e15115.

Jiang W, Johnson C, Jayaraman J, Simecek N, Noble J, Moffatt MF, et al. Copy number variation leads to considerable diversity for B but not A haplotypes of the human KIR genes encoding NK cell receptors. Genome Res. 2012;22(10):1845–54.

Nakimuli A, Chazara O, Farrell L, Hiby SE, Tukwasibwe S, Knee O, et al. Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) genes and their HLA-C ligands in a Ugandan population. Immunogenetics. 2013;65(11):765–75.

Norman PJ, Hollenbach JA, Nemat-Gorgani N, Guethlein LA, Hilton HG, Pando MJ, et al. Co-evolution of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I ligands with killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) in a genetically diverse population of sub-Saharan Africans. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(10):e1003938.

Jennes W, Verheyden S, Demanet C, Adjé-Touré CA, Vuylsteke B, Nkengasong JN, et al. Cutting edge: resistance to HIV-1 infection among African female sex workers is associated with inhibitory KIR in the absence of their HLA ligands. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2006;177(10):6588–92.

Bani M, Seket J, Kaabi H, Cherif G, Chaabane M, Bellali H, et al. Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) locus profiles in the Tunisian population. Hum Immunol. 2015;76(5):355–61.

Tukwasibwe S, Traherne JA, Chazara O, et al. Diversity of KIR genes and their HLA-C ligands in Ugandan populations with historically varied malaria transmission intensity. Malar J. 2021;20:111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-021-03652-y.

Sorgho PA, Djigma FW, Martinson JJ, Yonli AT, Nagalo BM, Compaore TR, et al. Role of Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) genes in stages of HIV-1 infection among patients from Burkina Faso. Biomol Concepts. 2019;10(1):226–36.

Yindom LM, Forbes R, Aka P, Janha O, Jeffries D, Jallow M, et al. Killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors and malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum in The Gambia. Tissue Antigens. 2012;79(2):104–13.

Naranbhai V, de Assis RD, Werner L, Moodley R, Hong H, Kharsany A, et al. Killer-cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptor (KIR) gene profiles modify HIV disease course, not HIV acquisition in South African women. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;16(1):27.

Gentle NL, Loubser S, Paximadis M, Puren A, Tiemessen CT. Killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I genetic diversity in four South African populations. Hum Immunol. 2017;78(7–8):503–9.

Mhandire K, Zijenah LS, Tshabalala M, Yindom LM, Mlambo T, Mhandire DZ, et al. KIR and HLA-C Genetic Polymorphisms Influence Plasma IP-10 Concentration in Antiretroviral Therapy-Naive HIV-Infected Adult Zimbabweans. OMICS. 2019;23(2):111–8.

Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Friedlaender FR, Ehret C, Ranciaro A, Froment A, et al. The genetic structure and history of Africans and African Americans. Science. 2009;324(5930):1035–44.

Cassatella MA, Gasperini S, Calzetti F, Bertagnin A, Luster AD, McDonald PP. Regulated production of the interferon‐γ‐inducible protein− 10 (IP‐10) chemokine by human neutrophils. Euro J Immunol. 1997;27(1):111–5.

Nemat-Gorgani N, Guethlein LA, Henn BM, Norberg SJ, Chiaroni J, Sikora M, et al. Diversity of KIR, HLA Class I, and Their Interactions in Seven Populations of Sub-Saharan Africans. J Immunol. 2019;202(9):2636–47.

Neville LF, Mathiak G, Bagasra O. The immunobiology of interferon-gamma inducible protein 10 kD (IP-10): a novel, pleiotropic member of the CXC chemokine superfamily. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997;8(3):207–19.

Alter G, Martin MP, Teigen N, Carr WH, Suscovich TJ, Schneidewind A, et al. Differential natural killer cell–mediated inhibition of HIV-1 replication based on distinct KIR/HLA subtypes. J Exp Med. 2007;204(12):3027–36.

Koehler RN, Alter G, Tovanabutra S, Saathoff E, Arroyo MA, Walsh AM, et al. Natural Killer Cell-Mediated Innate Sieve Effect on HIV-1: The Impact of KIR/HLA Polymorphism on HIV-1 Subtype-Specific Acquisition in East Africa. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(8):1250–4.

Gaudieri S, DeSantis D, McKinnon E, Moore C, Nolan D, Witt C, et al. Killer immunoglobulin-like receptors and HLA act both independently and synergistically to modify HIV disease progression. Genes Immun. 2005;6(8):683–90.

Zwolińska K, Błachowicz O, Tomczyk T, Knysz B, Gąsiorowski J, Zalewska M, et al. The effects of killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) genes on susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in the Polish population. Immunogenetics. 2016;68(5):327–37.

Boulet S, Sharafi S, Simic N, Bruneau J, Routy J-P, Tsoukas CM, et al. Increased proportion of KIR3DS1 homozygotes in HIV-exposed uninfected individuals. AIDS. 2008;22(5):595–9.

Martin Maureen P, Qi Y, Gao X, Yamada E, Martin JN, Pereyra F, et al. Innate partnership of HLA-B and KIR3DL1 subtypes against HIV-1. Nat Genet. 2007;39(6):733–40.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for managing advanced HIV disease and rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy, July 2017. 2017.

Sokoya T, Steel H, Nieuwoudt M, Rossouw T. HIV as a Cause of Immune Activation and Immunosenescence. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:1–16.

Zicari S, Sessa L, Cotugno N, Ruggiero A, Morrocchi E, Concato C, et al. Immune Activation, Inflammation, and Non-AIDS Co-Morbidities in HIV-Infected Patients under Long-Term ART. Viruses. 2019;11(3):200.

Mikulak J, Oriolo F, Zaghi E, Di Vito C, Mavilio D. Natural killer cells in HIV-1 infection and therapy. AIDS (London, England). 2017;31(17):2317.

Mavilio D, Benjamin J, Daucher M, Lombardo G, Kottilil S, Planta MA, et al. Natural killer cells in HIV-1 infection: dichotomous effects of viremia on inhibitory and activating receptors and their functional correlates. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100(25):15011–6.

Mulder N, Abimiku A, Adebamowo SN, de Vries J, Matimba A, Olowoyo P, et al. H3Africa: current perspectives. Pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine. 2018;11:59–66.

Choudhury A, Aron S, Botigué LR, Sengupta D, Botha G, Bensellak T, et al. High-depth African genomes inform human migration and health. Nature. 2020;586(7831):741–8.

Sirugo G, Williams SM, Tishkoff SA. The missing diversity in human genetic studies. Cell. 2019;177(1):26–31.

Campbell MC, Tishkoff SA. African genetic diversity: implications for human demographic history, modern human origins, and complex disease mapping. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2008;9:403–33.

Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Ranciaro A, Voight BF, Babbitt CC, Silverman JS, et al. Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe. Nat Genet. 2007;39(1):31.

Marin WM, Dandekar R, Augusto DG, Yusufali T, Heyn B, Hofmann J, et al. High-throughput Interpretation of Killer-cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptor Short-read Sequencing Data with PING. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021;17(8):e1008904-e.

Norman PJ, Hollenbach JA, Nemat-Gorgani N, Marin WM, Norberg SJ, Ashouri E, et al. Defining KIR and HLA Class I Genotypes at Highest Resolution via High-Throughput Sequencing. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99(2):375–91.

Bayley H. Nanopore sequencing: from imagination to reality. Clin Chem. 2015;61(1):25–31.

Wang Y, Yang Q, Wang Z. The evolution of nanopore sequencing. Front Genet. 2015;5:449.

Rhoads A, Au KF. PacBio sequencing and its applications. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13(5):278–89.

Barrientos M, Soria C. Population chart: Index Mundi; 2021 [updated 1st January 2020; Cited 2023 16th February].

Acknowledgements

Special thanks go to Miss Ann Ritah Namuganga for her efforts in reviewing the preliminary drafts of this manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge the financial support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common fund through the H3Africa consortium i.e., Nurturing Genomics and Bioinformatics Capacity in Africa – BReCA, Grant # U2RTW 010672 (Fogarty International Center) and the Collaborative African Genomics Network—CAfGEN, Grant # 5U54AI110398. The manuscript content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JM, MA, OJS, MLJ, DJ, DPK, GM, MM, NH, and JAH participated equally in the writing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final contents of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest concerning the authorship and publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplementary table S1. Table showing the population of Africa as of 1st January 2020. Source: [67] https://www.indexmundi.com/Map/?v=21&r=af&l=en.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mukisa, J., Amujal, M., Sande, O.J. et al. Killer cell immunoglobulin receptor diversity and its relevance in the human host’s response to HIV infection in African populations. transl med commun 8, 8 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41231-023-00141-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41231-023-00141-z