Abstract

Background

Medicinal plants are still used in developing countries, including the Philippines, to treat common diseases in the community. Anemia is a common disease encountered in the community. It is characterized by a lower-than-normal level of red blood cell count. This systematic review identified the medicinal plants used for anemia treatment in the Philippines.

Methods

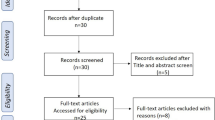

The study was conducted based on the PRISMA flow diagram, starting with a data search on electronic databases. The collected studies were screened based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The necessary information was extracted from the eligible research papers, and the studies’ quality was assessed through a developed quality assessment tool.

Results

A total of 20 ethnobotanical studies on medicinal plants used for anemia treatment were obtained from different provinces within the 12 regions of the Philippines. Most ethnobotanical studies were conducted in Region X (Northern Mindanao), CAR (Cordillera Administrative Region), and Region XIII (CARAGA), Philippines. The most common plant family is Convovulaceae, with nine records (21.95%), followed by Cucurbitaceae, with six records (14.63%), and Moringaceae, with five records (12.2%). The most common plant part used was the leaves. Others involved mixing different plant parts, with fruits and leaves being the most common combination. The most common route of administration utilized was drinking the decoction, followed by eating the plant. Most medicinal plants used to treat anemia in the Philippines had records of toxicologic (four species, 15.38%) or teratogenic (one species, 3.85%) properties. Eight plant species were reported as nontoxic (30.77%). In addition, ten plant species (38.46%) had no data on toxicity or teratogenicity.

Conclusion

There were only 20 ethnobotanical studies that documented the use of plants in treating anemia in the Philippines. This study listed several medicinal plants used in treating anemia in the Philippines. However, pharmacological and toxicological studies are still needed to determine their safety and efficacy in treating anemia in the community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Philippines is one of the mega-diverse countries in the world, having 75% of the world’s biodiversity, both in flora and fauna [1]. With rich flora, the Filipinos explored the use of these plants to treat diseases. This indigenous practice has been part of Filipino indigenous groups’ culture and has been handed down for generations [2]. Traditional medicine has remained popular for centuries, with around 80% of indigenous people still dependent on conventional medicine [3]. With the continuing reliance on more readily accessible plant-based medicine, rural dwellers sought out “parahilots”, town folk osteopathy practitioners [4], to cure diseases [2]. Several ethnobotanical studies surveyed the preparation and use of medicinal plants by geographically isolated tribes in the country [3]. However, most ethnobotanical studies in the Philippines only listed medicinal plants and their use. There were not a lot of ethnopharmacological investigations to validate the results of ethnobotanical surveys [5].

One of the prevailing conditions in the Philippines for which medicinal plants are still used is anemia. Anemia is characterized by a lower-than-normal red blood cell count level that leads to decreased oxygen blood levels, hemoglobin function abnormalities, and reduced hemoglobin and/or hematocrit content [6]. Based on the recommended cutoff set by the World Health Organization, anemia still affects one-third of the world’s population, with significant variations in low- and middle-income countries. It has now been considered a primary public health concern worldwide, particularly affecting certain vulnerable groups in developing countries with a high prevalence of poverty, malnutrition, and parasitism [7]. In 2019, it was estimated that there were 1.8 billion cases of anemia worldwide, which was more prevalent among women in all age groups [8].

The top three causes of anemia are beta-thalassemia, iron deficiency, and vitamin A deficiency. Most cases in the Philippines are caused by iron deficiency anemia (IDA). Identified causes are the lack of iron-rich foods and iron-fortified products [9]. In a local survey conducted in March 2021, the highest prevalence of IDA was recorded in pregnant women, followed by the geriatric (> 60 years) and children less than 5 years of age [10]. The consequences of anemia include high morbidity and mortality rates, particularly in women and children [11, 12], increased incidence of poor birth outcomes such as low birth weight and maternal and perinatal mortality [13, 14], poor physical performance in adults [15], cognitive and behavioral impairment in children [16], and compromised immune status [9].

Treatment for anemia largely depends on the identified cause, severity, patient characteristics, individual preferences, and geographical and cultural acceptance. Understanding and establishing anemia’s complex and diverse etiology is crucial to providing appropriate interventions. These interventions may not be limited to synthetic or commercially available drugs but should also cover medicinal plants used locally to treat anemia. Research on the use of medicinal plants in treating anemia in the Philippines is still limited, with the available data restricted only to small-scale studies among community dwellers in various parts of the country. In a survey conducted by Susaya-Garcia et al. (2018) [17], Momordica charantia L. and Moringa oleifera Lam. have been used by residents of remote villages in a small town in Jaro, Leyte, to treat anemia [17]. Similar studies have likewise found Alternanthera sessilis (L.) DC. [18], Lagerstroemia speciosa (L.) Pers., and Convolvulaceae Ipomoea sp. as anemia treatments among Ayta communities in Dinalupihan, Bataan [19]. In a survey of medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Pagadian City, Ipomea batatas (L.) Lam and Caesalpinia sappan L. are used in treating anemia [20]. Meanwhile, the indigenous Panay Bukidnon group utilizes Hibiscus acetosella Welw. ex Ficalho for anemia [21]. These studies documented the use of several medicinal plants in the country. However, only ten medicinal plants were clinically validated by the Philippine Institute of Traditional and Alternative Health Care (PITAHC) under the Department of Health (DOH) of the Philippines, and none were approved for anemia. Hence, this systematic review aims to identify the medicinal plants used to treat anemia in the Philippines as a reference list for plants that have yet to be clinically validated or recognized. Additionally, this review also included toxicologic and teratogenic data on plant species that can be used as a reference for their safety and the need for further testing.

Methods

Study selection

The PRISMA flow diagram [22] was used to guide this systematic review. From inception to December 5, 2021, a systematic literature review was conducted in three electronic databases: Ovid Medline, Scopus, and EBSCO CINAHL. A manual search was also conducted on Google Scholar. This search strategy was used in Scopus, EBSCO CINAHL, and Google Scholar: (ethnobot* OR ethnomed* OR ethnopharmacolo* OR “medicinal plan*”) AND (Philippin* OR Filipin*). For Ovid Medline, this search strategy was used: (ethnobotany OR ethnomedicine OR ethnopharmacology OR medicinal plants) AND (Philippines OR Filipino). However, this protocol was not registered in PROSPERO or other databases for systematic review and meta-analysis. The articles included in the study were only those written in English or Filipino. Observational studies were of particular interest because they provided primary information about ethnobotanical knowledge. Systematic reviews, literature reviews, letters to the editor, comments, and case reports were excluded.

Data extraction

Four reviewers —MCM, PTB, ECC, and RCG— independently reviewed the titles and abstracts. For each eligible study, full-text articles were obtained. Afterward, full-text articles were independently evaluated. All irrelevant articles were removed, and the reasons for their removal were documented. The following information was gathered from each included study: first author; year of publication; plant species; plant part used; method of preparation; route of administration; traditional use; ethnic group or users; and place of study. The results of this study were presented as tables and graphs generated using Microsoft Excel.

Assessment of the study quality

We used a previously developed quality assessment tool for ethnobotanical studies by Magtalas et al. (2022) [23]. This tool was adapted from a study by Timmer et al. (2003) [24]. It was tailored for ethnobotanical research and assessed the quality of ethnobotanical research as low, acceptable, or high (Table 1). The quality assessment tool was composed of ten questions evaluating the quality of the study objectives, the study design, the completeness of the description of the study area and population, the details of the methods that will allow replication of the study, the calculation of the sample size, the taxonomic classification of plants used in the study, a sufficient explanation of the results, and whether the results support the conclusions. However, it is vital to note that an assessment of the risk of bias in each study was not performed.

Results

The initial data search provided 498 studies, with 434 obtained from Scopus (68.07%), 28 from EBSCO CINAHL (5.62%), and 67 from OVID Medline databases (13.45%). In addition, 64 studies (12.85%) were obtained from the manual search on other platforms, including Google Scholar. After full-text analysis, only 20 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis (Fig. 1). The qualitative synthesis and summary of the full-text analysis of the studies included in this review are shown in Table 2 and Additional file 1: Table S1, respectively.

PRISMA flowchart of the study. Eligible studies were included based on the following inclusion criteria: (i) ethnobotanical studies conducted in the Philippines; (ii) the study included medicinal plants used in the management of anemia; (iii) the study has sufficient data regarding the species of the medicinal plants, parts used, method of preparation, and route of administration

Annual trends in the number of ethnobotanical studies

Ethnobotanical studies on anemia treatment in the Philippines gradually increased in the past years. The oldest data recorded was a study by Connie Cox Bodner and Roy E. Gereau [25], entitled “A contribution to Bontoc ethnobotany”, which pioneered the studies in this field. Between 1988 and 2014, research activities were still limited, with only six related studies documented. However, beginning in 2015, there was an alternate rise and fall in the published literature before it peaked in 2018 with three research studies. In contrast, there was a significant drop in 2019, which quickly recovered a year later, with three publications. Though the trend suggested a continuously growing number of studies performed on ethnobotanical medicine throughout the years, there is still a significant gap between the number of published research and the number of ethnic groups in the Philippines that must be studied (Fig. 2).

Geographical distribution of studies

The ethnobotanical studies on medicinal plants used for anemia treatment were obtained from different provinces within the 12 regions of the Philippines. Region X (Northern Mindanao), home to the Higaonons, Maranaos, Subanens, and Talaandig tribes, had the highest number of studies, with a total of five (25%) papers originating from the region. Region X was followed by the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) with four (20%), Region XIII (Caraga) with two (10%), and with only one (5%) ethnobotanical study, each originating from Region I (Ilocos Region), Region II (Cagayan Valley), Region III (Central Luzon), Region IV-A (CALABARZON), the National Capital Region (NCR), Region VI (Western Visayas), Region VIII (Eastern Visayas), Region IX (Zamboanga Peninsula), and Region XII (SOCCKSARGEN). Meanwhile, no research outputs were obtained from Regions IV-B (MIMAROPA), V (Bicol Region), VII (Central Visayas), XI (Davao Region), and the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) (Fig. 3).

Quality assessment of the studies

The result showed that out of the 20 ethnobotanical studies obtained, 17 (85.0%) of the papers reviewed were of high quality. Meanwhile, the remaining three (15.0%) papers had regular or acceptable quality, implying that all papers gathered have good quality and reproducibility. Unfortunately, nine (45.0%) papers did not have their plant specimen verified by a taxonomist (Fig. 4; Additional file 1: Table S2).

Most common plant families, genera, and species of medicinal plants used to treat anemia in the Philippines

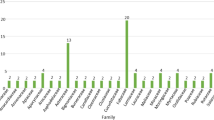

A total of 22 plant families, 22 genera, and 26 species were included in this systematic review. Convovulaceae was the most frequently mentioned plant family, with nine records (21.95%), followed by Cucurbitaceae with six records (14.63%), Moringaceae with five records (12.2%), and Solanaceae and Lamiaceae with two records each (4.88%). (Fig. 5A). The most common plant genera (Fig. 5B) were Ipomoea, with nine records (21.95%), Momordica, with six records (14.63%), Moringa, with five mentions (12.2%), and Solanum and Coleus, with two records (4.88%) each. Similarly, I. batatas (L.) Lam. was the most frequently mentioned plant species, with seven records (17.07%), followed by Momordica charantia L., with six (14.63%), and Moringa oleifera Lam., with five (12.2%) records (Fig. 5C).

Most common plant parts used, route of administration, method of preparation of medicinal plants used to treat anemia in the Philippines

The whole plant, single plant parts, or mixed plant parts can be used in medicinal plant preparations to treat anemia. Thirty-two (75.61%) ethnobotanical records used only a single plant part, and one used the whole plant itself (2.44%). The most common single plant part used was the leaf (19 records, 46.34%), followed by the shoots, roots, and fruits (three records each, 7.32%), then the bark (two records, 4.89%), and lastly, the twig (one record, 2.44%) (Fig. 6A). Meanwhile, nine records involved the use of mixed plant parts, with fruit and leaf as the most common combination (three records, 7.32%), followed by leaf and shoot (two records, 4.89%), leaf and seed (two records, 4.89%), and the less common bark and leaf (one record, 2.44%) and bark, flower, and seed (one record, 2.44%) combinations (Additional file 1: Figure S1A).

The route of administration was grouped into two categories: (1) plants with a single route of administration (32 records, 90.24%) (Fig. 6B), and (2) plants with two or more steps followed for the administration (three records, 7.32%) (Additional file 1: Figure S1B). The single routes of administration utilized were as follows: drinking (21 records, 51.22%), followed by eating (16 records, 39.02%). Meanwhile, for the second category, one record (2.44%) for each route of administration was recorded. These two-step administrations included: (1) eat cooked leaves as a vegetable; drink a decoction of leaves; (2) eat cooked leaves and drink juice; (3) eat cooked leaves or fruits as a vegetable; drink a decoction of leaves; and (4) eat fresh or cooked leaves or seeds as vegetables; drink a decoction of leaves.

The methods of plant preparation were divided into two categories: (1) plants prepared in a single step with 36 records obtained (Fig. 6C); and (2) plants prepared in two separate steps to produce two separate products with five records obtained (Additional file 1: Figure S1C). For the plants prepared in a single step, the most common method employed is decoction (19 records, 46.34%), followed by cooking (ten records, 24.39%), then harvesting (three records, 7.32%), extracting (two records, 4.88%), then washing (one record, 2.44%), and steaming (one record, 2.44%). One record was obtained for each of the multi-step methods of preparation, which include: (1) cooking leaves and fruit to make a decoction of the leaf; (2) cooking leaves and seed to make a decoction of leaves; (3) cooking and decoction; (4) cooking or juice (squeezing to get sap); and (5) decoction, juice, and cooking for the second category.

Toxicity and teratogenic properties of medicinal plants used to treat anemia in the Philippines

The toxicologic and teratogenic data of the plants used for anemia were determined through a literature search to provide information on the safety of these medicinal plants. Sixteen (61.5%) plant species had toxicologic and teratogenic data, whereas ten plant species (38.5%) did not (Additional file 1: Table S3). Various methods were utilized to assess the toxicity and teratogenicity of plant species used to treat anemia. Of the 19 reviewed preclinical studies for the toxicity and teratogenicity of the plants, 15 (78.94%) were conducted in vivo, and four (21.05%) were in vitro. The most common animal model used was Wistar rats (seven records, 36.8%), followed by Swiss mice (three records, 15.8%), then Sprague–Dawley rats (two records, 9.1%), and zebrafish embryos (two records, 9.1%), and lastly, Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) mice (one record, 4.5%). Meanwhile, for cytotoxicity assays, in vitro models (each mentioned once) include the human carcinoma cell lines HEp-2, Caco-2, and T84; mouse melanoma B16F10 cells and human dermal CCD-986sk fibroblasts; L929 fibroblasts; and the HeLa cell line. The most common treatment was the acute toxicity test (eight records, 36.4%), followed by the acute oral toxicity test (two records, 9.1%), the subacute toxicity test (two records, 9.1%), and the MTT assay (two records, 9.1%). Moreover, among the reported species, most of them were nontoxic. Of the rest, five (22.7%) were toxic, one (4.5%) was teratogenic, and one (4.5%) was both toxic (embryotoxic) and teratogenic (Fig. 7).

The data on toxicity and teratogenicity of the three most common species are presented in Table 3. L929 fibroblasts were used as an in vitro model in the study of I. batatas (L.) Lam. In contrast, only in vivo models, such as Sprague–Dawley rats, Wistar albino rats, and zebrafish embryos, were used to study M. charantia L. and M. oleifera Lam. In the MTT assay conducted on L929 fibroblasts by Moura et al. (2020) [26], the extract from the purple variety of I. batatas (L.) Lam. did not have cytotoxic potential, while the extract from the white variety did, at a concentration of 1000 µg/mL after 27-h treatment. M. charantia L., on the other hand, was considered teratogenic after providing water extracts of the whole unripe fruit to mice [27]. Specifically, M. charantia L. affected the development of the reproductive organs, and weight changes were observed in several organs, such as the brain, liver, kidney, lung, spleen, and heart [27]. Meanwhile, M. oleifera Lam. was considered nontoxic after an acute oral toxicity test done in Wistar albino rats upon oral administration of an aqueous methanolic leaf extract at a dose of 2000 mg/kg [28]. However, in a study involving Sprague–Dawley rats, given 1000 mg/kg and 3000 mg/kg doses, M. oleifera Lam. was considered genotoxic, but when ingested < 1000 mg/kg, it was considered safe [29]. Meanwhile, dilutions of M. oleifera Lam. leaf and bark extracts in embryo water resulted in toxic effects on zebrafish embryos [30]. The qualitative synthesis of the studies with data on plants used for anemia in the Philippines is presented in Additional file 1: Table S4.

Discussion

The initial literature search provided 402 results and only 20 studies were included in the qualitative analysis after eligibility screening. And as seen in the annual trend of the number of ethnobotanical studies done on plants used for anemia, there remains a big gap to fill in on this data. Since its inception in 1988, few anemia-related ethnobotanical studies have been conducted in the Philippines. Meanwhile, we have obtained the most ethnobotanical studies locally documenting the tribes in Region X (Northern Mindanao) and the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR). With a rich culture, there are more tribes to explore yet to fill the research gap. These ethnobotanical surveys cover only some of the regions in the Philippines; hence, there is a huge possibility that other plants used for anemia still need to be documented.

Several studies documented the pharmacological effects of bioactive compounds in traditionally used plants in iron deficiency anemia. The anti-anemic activity of the studied ethnomedicinal plants, particularly I. batatas (L.) Lam. was evaluated through hematological indices, namely hemoglobin, hematocrit, red blood cell (RBC), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), in an experimental study performed on albino rats, where it was observed that the n-hexane leaf extract of I. batatas (L.) Lam. triggered regeneration of RBC, hematocrit, hemoglobin, MCV, and MCH [31]. Moreover, in an Indonesian clinical study involving pregnant women, I. batatas (L.) Lam. leaf decoction increased the hemoglobin levels [32, 33].

Another study reported how the iron content in the Moringa leaves acts as the primary nutrient in hematopoiesis in the spinal cord. Likewise, the protein and amino acid content in Moringa leaves acts as hematopoietic growth factors. Its leaves reported a high protein and amino acid content, vital in managing blood cell differentiation and proliferation. Furthermore, the vitamin C content in Moringa leaf extract also increases iron absorption in the body [34]. In a study done in male Wistar rats, it was reported that dietary iron from Moringa leaves was more effective in overcoming iron deficiency in rats than ferric citrate, which suggests its possible effects on the expression of liver hepcidin mRNA expression [35]. Other medicinal plant families, such as Convovulaceae, Cucurbitaceae, and Amaranthaceae, are believed to contain significant amounts of iron, vitamins, and minerals, which help elevate hemoglobin percentage in the blood.

Literature on the toxicologic and teratogenic data for the three most commonly cited plant species was available. However, the safety and efficacy of these documented medicinal plants in humans still need to be investigated due to the scarcity of preclinical and clinical studies. This systematic review determined the three most cited plant species, which include I. batatas (L.) Lam., M. charantia L., and M. oleifera Lam. In an in vitro study documenting the cytotoxicity of two varieties of I. batatas (L.) Lam., the MTT assay showed the cytotoxic potential of the white variant at 1000 μg/ml [26]. Given this result, we suggest further investigating the cytotoxicity of the two variants since the study used lyophilized plants while I. batatas (L.) Lam. is commonly cooked. Hence, heat may induce changes in the biochemical properties of the plant [26].

Meanwhile, one study documented the teratogenicity of M. charantia L. upon the provision of water extracts of the whole unripe fruit to mice, but the doses of the whole unripe fruit were not specified. Hence, its teratogenicity data was insufficient. Moreover, the study recorded the weights of the internal organs and revealed a reduction in the weight of the brain, liver, lungs, kidneys, and spleen while the heart’s weight increased. It was later concluded that the teratogenicity of the unripe fruit depends on the gestation period during which it was ingested and showed that most malformations occurred on days seven, 11, and 13; however, the duration of treatment should ideally be increased to cover the span of organogenesis. It is also imperative not to draw generalized conclusions based on one study. Therefore, we recommend confirming these data further to validate the results.

Lastly, the toxic dose threshold for M. oleifera Lam. should be clarified since one study documented its safety when < 1000 mg/kg per body weight was ingested [29], while another reported that it is nontoxic at a dose of 2000 mg/kg [28]. Hence, its safe dose and toxic dose should be elucidated further. Using a different animal model (i.e., zebrafish embryo), dilutions of M. oleifera Lam. leaf and bark extracts were considered toxic. With these, the toxicity and safety of M. oleifera Lam. should be further explored. If possible, more varied dose formulations and animal models or cell lines should be examined to ensure its toxicity. The continued use of these plants may pose risks to local tribes, as some have been described as teratogenic and toxic at specific doses. Fortunately, most were deemed safe among the identified species with toxicologic and teratogenic data. However, considering the most used plants, there are dose limits to which the plant can be regarded as safe (e.g., M. oleifera Lam.). Hence, precaution should be practiced when using it. Moreover, it is crucial to consider the type of solvents used in plant extraction, as these may be teratogenic and toxic. In the presence of varieties or local variants, genomic studies should also be conducted to ensure the identity of the plant described. When designing toxicologic and teratogenic studies, the method of preparation by which the plant is ingested should be considered. These safety and/or toxicity data (i.e., therapeutic dose), when studied further, should be relayed to the local tribes actively engaged in the use of these plants to lessen the risks of plant toxicity.

With emerging diseases and the demand for low-cost medicines in the current situation, the use of ethnomedicinal plants in the Philippines is inevitable. Even though this systematic review included only articles written in English or Filipino and excluded systematic reviews, literature reviews, letters to the editor, comments, and case reports, we identified the commonly utilized ethnomedicinal plant species, parts of the plants involved, their suggested method of preparation, and the indigenous communities that mainly used these for treating anemia. We also discovered that only a few anemia-related ethnobotanical studies were conducted in the Philippines. Literature is available on the toxicologic and teratogenic data for the three most commonly used plant species. However, their safety and efficacy remain questionable due to preclinical and clinical data scarcity. In addition, the data gathered highlighted the crucial role of various ethnomedicinal plants and how these remain a significant source of medicine among rural dwellers because of the limited means of modern medicine. Notably, most recorded plants grew in the wild and have received little attention in the literature [36]. This means there are still several other unexamined ethnomedicinal plants that can be potentially used for treating anemia. Indeed, there needs to be documentation of the medicinal plants claimed by indigenous communities, which can pave the way for researchers to discover and develop these plant-based medicines [37, 38] in addition to the government’s food fortification efforts in addressing the anemia burden in the country [38]. This review will also help conserve the geographical areas where these plant species naturally thrive and preserve the knowledge and practices related to anemia management. To fill in the gap in the toxicologic and/or teratogenic data, we recommend that the previously documented plants be analyzed first. In turn, this study can guide future research activities to examine active compounds and other potential plant properties that can later be added to the list of medicinal plants officially recognized by the Department of Health—PITAHC and the subsequent incorporation of these into our current health system as complementary medicine.

Conclusion

This systematic review gathered 20 ethnobotanical studies in the Philippines that reported medicinal plants used to treat anemia. There was an observed increase in ethnobotanical studies through the years. However, a significant research gap exists on the medicinal plants used to treat anemia. There are still regions in the Philippines without ethnobotanical studies related to anemia. This systematic review showed the abundance of medicinal plants used in treating anemia in the Philippines. However, pharmacological and toxicological studies are still needed to determine and verify the safety and efficacy of these medicinal plants in treating anemia in the community. Lastly, this study will guide future researchers to look closely at untapped medicinal plants and review their properties, emphasizing safety and toxicity for humans.

Availability of data and materials

All data related to this study are included in the manuscript and the additional file.

Abbreviations

- BARMM:

-

Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao

- CAR:

-

Cordillera Administrative Region

- CALABARZON:

-

Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal, and Quezon

- DOH:

-

Department of Health

- ICR mice:

-

Institute of Cancer Research mice

- IDA:

-

Iron deficiency anemia

- MCH:

-

Mean corpuscular hemoglobin

- MCHC:

-

Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration

- MCV:

-

Mean corpuscular volume

- MIMAROPA:

-

Mindoro Occidental, Mindoro Oriental, Marinduque, Romblon, and Palawan

- NCR:

-

National Capital Region

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- PITAHC:

-

Philippine Institute of Traditional and Alternative Health Care

- RBC:

-

Red blood cell

- SOCCKSARGEN:

-

South Cotabato, Cotabato, Sultan Kudarat, Sarangani, and General Santos City

References

Ani PA, Castillo MB. Revisiting the State of Philippine Biodiversity and the Legislation on Access and Benefit Sharing, FFTC Agric. Policy Platf. 2020. https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/1836.

Belgica TH, Suba M, Alejandro GJ. Quantitative ethnobotanical study of medicinal flora used by local inhabitants in selected Barangay of Malinao, Albay, Philippines. Biodiversitas J Biol Divers. 2021;5:6.

Baleta FN, Donato JG, Bolaños JM. Awareness, utilization and diversity of medicinal plants at Palanan, Isabela, Philippines. J Med Plants Stud. 2016;4:265–9.

Arce WF. The structural bases of compadre characteristics in a Bikol Towns, Philipp Sociol Rev. 1973; 51–71.

Sofowora A, Ogunbodede E, Onayade A. The role and place of medicinal plants in the strategies for disease prevention, African. J Tradit Complement Altern Med AJTCAM. 2013;10:210–29. https://doi.org/10.4314/AJTCAM.V10I5.2.

Keohane EM, Walenga JM, Otto CN. Rodak’s Hematology: Clinical Principles and Applications, 6th ed., Elsevier, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-53045-3.00001-5.

Kassebaum NJ, Jasrasaria R, Naghavi M, Wulf SK, Johns N, Lozano R, Regan M, Weatherall D, Chou DP, Eisele TP, Flaxman SR, Pullan RL, Brooker SJ, Murray CJL. A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. 2014;123:615–24. https://doi.org/10.1182/BLOOD-2013-06-508325.

Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Noori M, Nejadghaderi SA, Karamzad N, Bragazzi NL, Sullman MJM, Abdollahi M, Collins GS, Kaufman JS, Grieger JA. Burden of anemia and its underlying causes in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J Hematol Oncol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13045-021-01202-2.

Angeles-Agdeppa I, Sun Y, Denney L, Tanda KV, Octavio RAD, Carriquiry A, Capanzana MV. Food sources, energy and nutrient intakes of adults: 2013 Philippines National Nutrition Survey. Nutr J. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12937-019-0481-Z.

Philippine Statistics Authority, SDG Watch Philippines: Goal 2: End Hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture. Philipp. Stat. Auth. (2021). Date accessed: 03 July 2022, from https://psa.gov.ph/system/files/Goal2.pdf.

Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, De Onis M, Ezzati M, Grantham-Mcgregor S, Katz J, Martorell R, Uauy R. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet (London, England). 2013;382:427–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X.

Scott SP, Chen-Edinboro LP, Caulfield LE, Murray-Kolb LE. The impact of anemia on child mortality: an updated review. Nutrients. 2014;6:5915–32. https://doi.org/10.3390/NU6125915.

Haider B, Olofin I, Wang M, Spiegelman D, Ezzati M, Fawzi W. Anaemia, prenatal iron use, and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3443–f3443. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f3443.

Rasmussen KM. Is there a causal relationship between iron deficiency or iron-deficiency anemia and weight at birth, length of gestation and perinatal mortality? J Nutr. 2001;131:590S-601S. https://doi.org/10.1093/JN/131.2.590S.

Haas JD, Brownlie T IV. Iron deficiency and reduced work capacity: a critical review of the research to determine a causal relationship. J Nutr. 2001;131:676S-688S. https://doi.org/10.1093/JN/131.2.676S.

Walker SP, Wachs TD, Meeks Gardner J, Lozoff B, Wasserman GA, Pollitt E, Carter JA. Child development: risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. Lancet (London, England). 2007;369:145–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60076-2.

Susaya-Garcia J, Borja N, Sevilla-Nastor JB, Villanueva JD, Peyraube N. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants and perceptions on plant biodiversity conservation in Leyte, Philippines. J Hum Ecol. 2018;7:26–42.

Carag H, Buot I Jr. A checklist of the orders and families of medicinal plants in the Philippines. Sylvatrop. 2017;27:39–83.

Tantengco OAG, Condes MLC, Estadilla HHT, Ragragio EM. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by Ayta communities in Dinalupihan, Bataan, Philippines. Pharmacogn J. 2018;10:859–70. https://doi.org/10.5530/pj.2018.5.145.

Fabie-Agapin J. Medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Pagadian City, Zamboanga del Sur, Philippines. Philipp J Sci. 2019;149:83–9. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3625332.

Cordero C, Ligsay A, Alejandro GJD. Ethnobotanical documentation of medicinal plants used by the Ati tribe in Malay, Aklan, Philippines. J Complement Med Res. 2020;11:170. https://doi.org/10.5455/jcmr.2020.11.01.20.

Page M, Mckenzie J, Bossuyt P, Boutron I, Hoffmann T, Mulrow C, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff J, Akl E, Brennan S, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw J, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu M, Li T, Loder E, Mayo-Wilson E, Mcdonald S, Moher D, The PRISMA. statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;372(2021):n71–n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Magtalas MC, Balbin PT, Cruz EC, Guevarra RC, Cruz ARDP, Silverio CE, Lee KY, Tantengco OAG. A systematic review of ethnomedicinal plants used for pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum care in the Philippines. Phytomedicine Plus. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phyplu.2023.100407.

Timmer A, Sutherland LR, Hilsden RJ. Development and evaluation of a quality score for abstracts. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-3-2.

Bodner CC, Gereau RE. A contribution to Bontoc ethnobotany. Econ Bot. 1988;42:307–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02860159.

Moura IO, Santana CC, Lourenço YRF, Souza MF, Silva ARST, Dolabella SS, de Oliveirae Silva AM, Oliveira TB, Duarte MC, Faraoni AS. Chemical characterization, antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity of the unconventional food plants: sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) leaf, major gomes (Talinum paniculatum (Jacq.) Gaertn.) and Caruru (Amaranthus deflexus L.). Waste Biomass Valorization. 2020;12:2407–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12649-020-01186-z.

Uche-Nwachi EO, McEwen C. Teratogenic effect of the water extract of bitter gourd (Momordica charantia) on the Sprague Dawley rats, African. J Tradit Complement Altern Med AJTCAM. 2009;7:24–33. https://doi.org/10.4314/AJTCAM.V7I1.57228.

Okumu M, Mbaria J, Kanja L, Gakuya D, Kiama S, Okumu F, Okumu P. Acute toxicity of the aqueous-methanolic Moringa oleifera (Lam) leaf extract on female Wistar albino rats. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2016;5:1856–61. https://doi.org/10.18203/2319-2003.ijbcp20163153.

Asare GA, Gyan B, Bugyei K, Adjei S, Mahama R, Addo P, Otu-Nyarko L, Wiredu EK, Nyarko A. Toxicity potentials of the nutraceutical Moringa oleifera at supra-supplementation levels. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139:265–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JEP.2011.11.009.

David CRS, Angeles A, Angoluan RC, Santos JPE, David ES, Dulay RMR. Moringa oleifera (Malunggay) water extracts exhibit embryotoxic and teratogenic activity in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Embryo Model. Der Pharm Lett. 2016. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13657.34403.

Gabriel BO, Idu M. Antioxidant property, haematinic and biosafety effect of Ipomoea batatas Lam. leaf extract in animal model. Beni-Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43088-021-00161-4.

Cotoraci C, Ciceu A, Sasu A, Hermenean A. Natural antioxidants in anemia treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:1883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22041883.

Hutabarat NC, Widyawati MN. The effect of sweet potato leaf decoction and iron tablet against increased hemoglobin levels in pregnant women. Indones J Heal Res. 2018;1:59–65. https://doi.org/10.32805/ijhr.2018.1.2.11.

Mun’Im A. Anti-anemia effect of standardized extract of Moringa oleifera Lam. leaves on aniline induced rats. Pharmacogn J. 2016;8:255–8. https://doi.org/10.5530/pj.2016.3.14.

Saini RK, Manoj P, Shetty NP, Srinivasan K, Giridhar P. Dietary iron supplements and Moringa oleifera leaves influence the liver hepcidin messenger RNA expression and biochemical indices of iron status in rats. Nutr Res. 2014;34:630–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2014.07.003.

Abe R, Ohtani K. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants and traditional therapies on Batan Island, the Philippines. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;145:554–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JEP.2012.11.029.

Balangcod T, Balangcod K. Ethnomedicinal plants in Bayabas, Sablan, Benguet Province, Luzon, Philippines. Electron J Biol. 2015;11:63–73.

Detzel P, Wieser S. Food fortification for addressing iron deficiency in Filipino children: benefits and cost-effectiveness. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66:35–42. https://doi.org/10.1159/000375144.

Alduhisa GU, Demayo CG. Ethnomedicinal plants used by the Subanen tribe in two villages in Ozamis City, Mindanao, Philippines. Pharmacophore. 2019;10:28–42.

Balangcod T, Balangcod AK. Ethnomedical knowledge of plants and healthcare practices among the Kalanguya tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, Philippines. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2011;10:227–38.

Balangcod T, Balangcod K. Plants and culture: plant utilization among the local communities in Kabayan, Benguet Province, Philippines. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2018;17:609–22.

Caunca ES, Balinado LO. The practice of using medicinal plants by local herbalists in Cavite, Philippines. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2021;20:335–43.

Dapar MLG, Alejandro GJD, Meve U, Liede-Schumann S. Quantitative ethnopharmacological documentation and molecular confirmation of medicinal plants used by the Manobo tribe of Agusan del Sur, Philippines. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2020;16:1–60. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13002-020-00363-7.

de Guzman AA, Jamanulla CEVA, Sabturani AM, Madjos G. Ethnobotany and physiological review on folkloric medicinal plants of the Visayans in Ipil and Siay, Zamboanga Sibugay, Philippines. Philipp Int J Herb Med. 2020;8:8–16.

Ducusin MB. Ethnomedicinal knowledge of plants among the indigenous peoples of Santol, La Union, Philippines. Electron J Biol. 2017;13:360–82.

Flores RL, Legario RA, Malagotnot DBM, Peregrin K, Sato RA, Secoya ER. Ethnomedicinal study of plants sold in Quiapo, Manila. Philippines. 2016;206(4):359–65.

Langenberger G, Prigge V, Martin K, Belonias B, Sauerborn J. Ethnobotanical knowledge of Philippine lowland farmers and its application in agroforestry. Agrofor Syst. 2009;76:173–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-008-9189-3.

Naive MAK, Binag SDA, Alejandro GJD. Plants with benefits: Ethnomedicinal plants used by the Talaandig tribe in Portulin, Pangantucan, Bukidnon, Philippines. Indian J Tradit Knowl. 2021;20:754–66. https://doi.org/10.56042/ijtk.v20i3.26584.

Odchimar NMO, Nuñeza OM, Uy MM, Senarath WTPSK. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants used by the Talaandig Tribe in Brgy Lilingayon, Valencia City, Bukidnon, Philippines. Asian J Biol Life Sci. 2017;6:358–64.

Olowa L, Torres MA, Aranico E, Demayo C. Medicinal plants used by the Higaonon tribe of Rogongon, Iligan City, Mindanao, Philippines. Adv Environ Biol. 2012;6:1442–9.

Olowa L, Demayo CG. Ethnobotanical uses of medicinal plants among the Muslim Maranaos in Iligan City, Mindanao, Philippines. Adv Environ Biol. 2015;9:204–15.

Ong HG, Kim Y-D. Quantitative ethnobotanical study of the medicinal plants used by the Ati Negrito indigenous group in Guimaras island, Philippines. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;157:228–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.015.

Paraguison L, Tandang DN, Alejandro GJ. Medicinal Plants used by the Manobo Tribe of Prosperidad, Agusan Del Sur, Philippines: an Ethnobotanical Survey. Asian J Biol Life Sci. 2020;9:326–33. https://doi.org/10.5530/ajbls.2020.9.49.

Rubio M, Arcebal N. Ethnomedicinal plants used by traditional healers in North Cotabato, Mindanao, Philippines. J Biodivers Environ Sci. 2018;13:74–82.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ms. Rachelle C. Guevarra for her prompt assistance with the study search, data extraction, and result formulation.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Mid Sweden University. This study did not receive funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MCM, PTB, ECC, RCG, RFC, and OAGT designed the study. MCM, PTB, ECC, and OAGT performed the literature search. MCM, PTB, ECC, RCG, AKGB, JPG, KYL, and OAGT analyzed the collected data. MCM, PTB, ECC, RCG, AKGB, JPG, and OAGT wrote the first draft of the manuscript. KYL and OAGT reviewed the draft manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This manuscript is a systematic review and does not require ethics clearance from the institutional review board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Most common plant parts used (mixed) (A), routes of administration with two separate steps (B), and other modes of preparation (C). Table S1. Summary of full-text analysis. Table S2. Quality assessment of the studies with data on plants used for anemia in the Philippines. Table S3. Toxicologic and teratogenic data of plants used for anemia in the Philippines. Table S4. Qualitative synthesis of the studies with data on plants used for anemia in the Philippines.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Magtalas, M.C., Balbin, P.T., Cruz, E.C. et al. Ethnomedicinal plants used for the prevention and treatment of anemia in the Philippines: a systematic review. Trop Med Health 51, 27 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-023-00515-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-023-00515-x