Abstract

Background

Peritonitis is a common and clinically important complication in patients receiving peritoneal dialysis (PD). Antibiotic administration is essential for PD-related peritonitis, but routes of administration have not been established enough. Here, we performed a systematic review to assess the efficacy and safety of intraperitoneal (IP) antibiotic administration compared to intravenous (IV) antibiotic administration in patients with PD-related peritonitis.

Methods

Cochrane CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and Ichushi-Web were searched in June 2017. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were followed, and articles were screened by four independent reviewers.

Results

Two randomized controlled trials (113 patients) were identified. IP antibiotic administration was more effective than IV antibiotic administration. The pooled risk difference between IP and IV was 0.13 (95% CI − 0.17 to 0.43). Safety assessment indicated less frequency of side effects in patients receiving IP antibiotic administration. The pooled risk ratios of IV to IP regarding adverse drug reaction-related and administration route-related side effects were 5.13 (0.63 to 41.59) and 3.00 (0.14 to 65.90), respectively.

Conclusion

The systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that IP antibiotic administration is more effective and safer in patients with PD-related peritonitis compared to IV antibiotic administration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a well-established modality of renal replacement therapy for patients with end-stage renal disease. The utilization and popularization of PD are rapidly growing, particularly in developing countries, where the number of patients receiving PD has increased more than 2-fold during the last decade [1]. Although technical improvements and innovations of PD-related clinical practice have significantly decreased PD-associated infectious complications including PD-related peritonitis and exit-site/tunnel infection, they are still one of the major barriers which adversely affects both technical and patient survival in PD patients [2, 3].

The International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) published guidelines and recommendations about PD-related peritonitis in 1983, which were revised in 1993, 1996, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2016 [3,4,5,6,7,8]. The most recent recommendations published in 2016 are organized into the following five sections: (1) peritonitis rate, (2) prevention of peritonitis, (3) initial presentation and management of peritonitis, (4) subsequent management of peritonitis, and (5) future research. In practical cases of PD-related peritonitis, proper initial management consists of diagnosis, subsequent appropriate microbiological culture sampling, and prompt empirical antibiotic therapy, followed by antibiotic de-escalation in certain cases. Treatment intent of antibiotic administration is a rapid resolution of inflammation to protect the peritoneal membrane. As an empirical regimen, a proportional meta-analysis revealed that the combination of a glycopeptide (vancomycin or teicoplanin) and ceftazidime is considered to be superior to other regimens [9].

In terms of antibiotic administration, intraperitoneal (IP) administration is preferred (GRADE 1B) in the most recent ISPD recommendations, without cases presenting systemic sepsis [3]. In general, IP administration is considered to bring about higher peritoneal drug concentration than intravenous (IV) administration [3]. Moreover, IP administration is available without vascular puncture. Several clinical studies comparing IP administration with IV administration for PD-related peritonitis revealed controversial results [10, 11], and the clinical advantage of the recommended IP administration has not been established enough. Here, we performed a systematic review to assess the efficacy and safety of IP administration compared to IV administration in patients with PD-related peritonitis.

Methods

Compliance with reporting guidelines

We conducted a systematic review of the relevant literature in agreement with the recommendations listed in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [12]. Exemption from the review was granted by the Ethics Committee because this study did not involve patient intervention and confidential personal data collection.

Research question and eligibility criteria

The research question of this review was: “Is IP antibiotic administration superior in efficacy and safety to IV administration in patients with PD-related peritonitis?” We included published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing IP administration with IV, of any race and gender, in any language, and from any country. We excluded observational studies, case reports, and case series.

Outcomes of interest

The outcomes were treatment success (cure of peritonitis after antibiotic administration) and complication.

Search strategy and study selection

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE via PubMed, and NPO Japan Medical Abstracts Society (JMAS) databases. The search was performed in June 2017 (Cochrane CENTRAL and PubMed) and in April 2017 (JMAS) using the following suitable search terms: peritoneal dialysis, peritonitis, intraperitoneal injection/administration, intravenous injection/administration. Four reviewers (KM, HT, NW, and TK) independently screened the title and abstract of each study to select candidate studies, and the reviewers performed a full-text review to evaluate the eligibility of each candidate study.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The selected studies were independently assessed by four authors (KM, HT, NW, and TK) using the risk of bias assessment tool, as previously described (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0; available at www.cochrane-handbook.org), and discrepancies were resolved by consultation with HY and YT: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance and detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attention bias), selective reporting (reporting bias), and other potential biases.

Measurement of treatment effect

Data from each trial was analyzed using the risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for binary outcomes and using the mean difference for continuous outcomes.

Analysis and data synthesis

All analyses were conducted using Review Manager (RevMan) Version 5.3 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration).

Assessment of the certainty of evidence

We prepared a summary of findings table including an overall grading of evidence certainty for the outcomes, which was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [13, 14].

The recommendations follow the Grading of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system for the classification of the level of evidence and grade of recommendations in clinical guideline reports [15]. With each recommendation, the strength of the recommendation is indicated as level 1 (we recommend), level 2 (we suggest), or not graded, and the quality of the supporting evidence is shown as A (high quality), B (moderate quality), C (low quality), or D (very low quality).

Results

Search results

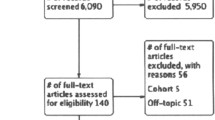

The described electronic search of the databases identified 171 candidate studies via the Cochrane CENTRAL, 1094 via PubMed, and 463 via JMAS databases. After the removal of duplicates and the selection by the reviewers, we identified two articles of RCT met the eligibility criteria (Table 1).

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 2. A total of 113 patients from the two RCTs published in 1987 and 1990 were included [16, 17]. Bailie et al. compared IP with IV as the initial antibiotic administration (vancomycin 1 g/body as a loading dose) for PD-related peritonitis. The patients in both groups were treated with maintenance IP antibiotic administration [16]. Bennett-Jones et al. compared IP (vancomycin 20 mg/L + tobramycin 4 mg/L in dialysate) with IV (vancomycin 0.5–1.0 g/body + tobramycin 1.0 mg/kg body weight) as the initial and maintenance antibiotic administration [17] (Table 1).

Risk of bias

The assessment of risk of bias of the included studies is shown in Table 2. In terms of “success in therapy,” “drug-related complication,” and “route-related complication,” the risk of bias domains of randomization, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors, and other sources in the two studies and of incomplete outcome data in one study were considered “unclear” because we could not find enough information to assess the domains. Blinding of participants was considered “high risk” because blinding was limited in the two studies. Reporting bias was also considered “high risk.” In one RCT, incomplete outcome data was considered “low risk” because all participants were traced during the study.

Effect and complication of interventions

We conducted a meta-analysis with the identified and included two RCTs (113 patients). IP antibiotic administration was more effective than IV administration. The pooled risk difference between IP and IV was 0.13 (95% CI − 0.17 to 0.43). Safety assessment indicated less frequency of side effects in patients receiving IP administration. The pooled risk ratios of IV to IP regarding adverse drug reaction-related and administration route-related side effects were 5.13 (0.63 to 41.59) and 3.00 (0.14 to 65.90), respectively (Fig. 1).

Discussion

PD-related peritonitis is a major complication of PD and is one of the leading causes of technical failure and mortality in patients receiving PD. To prevent serious clinical outcomes, proper management of peritonitis, including prompt diagnosis and empirical antibiotic therapy followed by subsequent management, is important. ISPD recommends empirical antibiotic therapy with a center-specific regimen covering both Gram-positive and Gram-negative microorganisms, immediately after appropriate microbiological sampling [3]. The current recommendations of antibiotics are vancomycin or first-generation cephalosporin for Gram-positive organism coverage, and third-generation cephalosporin or aminoglycoside for Gram-negative organism coverage [3]. In terms of antibiotic administration route, IP is preferred in ISPD recommendations, unless there are clinical presentations of systemic sepsis or a foreseeable delay (e.g., combination of catheter obstruction) in IP administration [3, 18].

While IP is a less common route than IV, oral or topic use of antibiotic administration in general clinical situations of infectious diseases, IP is regarded as a common and established antibiotic administration route in patients with PD-related patients. The usability of PD catheter as peritoneal access and the relative easiness of drug administration in outpatient clinics would contribute to the uniqueness. Oral antibiotic administration is also compatible with outpatient medical service, but it would be difficult to cover possible causative pathogens enough only with oral antibiotics. In addition, antibiotic treatment should aim for rapid resolution of inflammation to preserve the peritoneal membrane function, but oral administration generally requires additional time in drug absorption and intracorporeal drug delivery compared to IP and IV [19, 20]. IP antibiotic administration is an effective and practicable therapeutic approach to PD-related peritonitis. Efficacy and practical dosage of IP antibiotic administrations are recommended with published clinical experiences rather than pharmacokinetic studies, closely described in the current ISPD recommendations [3].

This study aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of IP antibiotic administration compared to IV administration in patients presenting PD-related peritonitis. We selected only two RCTs based on the eligibility criteria, and the efficacy of IV was not statistically significant compared to IP (Fig. 1). Safety was mainly affected by administration route-related complications. In addition, it should be noted that IP antibiotic administration is not covered by insurance at this time in Japan. In conclusion, the systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that IP antibiotic administration is more effective and safer in patients with PD-related peritonitis compared to IV antibiotic administration (GRADE 2C).

Availability of data and materials

Please contact the authors for data requests.

Abbreviations

- IP:

-

Intraperitoneal

- ISPD:

-

International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- PD:

-

Peritoneal dialysis

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

References

Jain AK, Blake P, Cordy P, Garg AX. Global trends in rates of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrols. 2012;23:533–44.

Mehrotra R, Devuyst O, Davies SJ, Johnson DW. The current state of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3238–52.

Li PK, Szeto CC, Piraino B, de Arteaga J, Fan S, Figueiredo AE, et al. ISPD Peritonitis Recommendations: 2016 update on prevention and treatment. Perit Dial Int. 2016;36:481–508.

Keane WF, Everett ED, Golper TA, Gokal R, Halstenson C, Kawaguchi Y, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis treatment recommendations. 1993 update. The Ad Hoc Advisory Committee on Peritonitis Management. International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 1993;13:14–28.

Keane WF, Alexander SR, Bailie GR, Boeschoten E, Gokal R, Golper TA, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis treatment recommendations: 1996 update. Perit Dial Int. 1996;16:557–73.

Keane WF, Bailie GR, Boeschoten E, Gokal R, Golper TA, Holmes CJ, et al. Adult peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis treatment recommendations: 2000 update. Perit Dial Int. 2000;20:396–411.

Piraino B, Bailie GR, Bernardini J, Boeschoten E, Gupta A, Holmes C, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2005 update. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25:107–31.

Piraino B, Bernardini J, Brown E, Figueiredo A, Johnson DW, Lye WC, et al. ISPD position statement on reducing the risks of peritoneal dialysis-related infections. Perit Dial Int. 2011;31:614–30.

Barretti P, Doles JV, Pinotti DG, El Dib R. Efficacy of antibiotic therapy for peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis: a proportional meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:445.

Ballinger AE, Palmer SC, Wiggins KJ, Craig JC, Johnson DW, Cross NB, et al. Treatment for peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD005284.

Goffin E, Herbiet L, Pouthier D, Pochet JM, Lafontaine JJ, Christophe JL, et al. Vancomycin and ciprofloxacin: systemic antibiotic administration for peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis. Perit Dial Int. 2004;24:433–9.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–6.

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–94.

Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, et al. GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490.

Bailie GR, Morton R, Ganguli L, Keaney M, Waldek S. Intravenous or intraperitoneal vancomycin for the treatment of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis associated gram-positive peritonitis? Nephron. 1987;46:316–8.

Bennett-Jones DN, Russell GI, Barrett A. A comparison between oral ciprofloxacin and intra-peritoneal vancomycin and gentamicin in the treatment of CAPD peritonitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;26:73–6.

Muthucumarana K, Howson P, Crawford D, Burrows S, Swaminathan R, Irish A. The relationship between presentation and the time of initial administration of antibiotics with outcomes of peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients: the PROMPT Study. Kidney Int Rep. 2016;1:65–72.

Kays MB, Overholser BR, Mueller BA, Moe SM, Sowinski KM. Effects of sevelamer hydrochloride and calcium acetate on the oral bioavailability of ciprofloxacin. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:1253–9.

How PP, Fischer JH, Arruda JA, Lau AH. Effects of lanthanum carbonate on the absorption and oral bioavailability of ciprofloxacin. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:1235–40.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

KM, HT, NW, and TK mainly undertook this review. The literatures were screened independently by KM, HT, NW, and TK. HY and YT participated in the design of the study and performed the statistical analysis. MR and YI conceived the study. MT and HN participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Morimoto, K., Terawaki, H., Washida, N. et al. The impact of intraperitoneal antibiotic administration in patients with peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Replace Ther 6, 19 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-020-00270-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-020-00270-3