Abstract

Background

Autologous epidural blood patch (AEBP) is effective for post-dural-puncture headache (PDPH). In some cases, repeat procedures are required for complete cure. In rare instances, severe adverse effects can occur. We present a case of neurologically complicated AEBPs, one of which was performed at the interspace of unintentional dural puncture (UDP).

Case presentation

A 40-year-old primigravida sustained UDP at the L2–3 interspace during combined spinal-epidural anesthesia for a scheduled cesarean section. She developed PDPH and underwent a single AEBP at L3–4. The PDPH recurred and she required another AEBP at L2–3, after which she reported radicular pains. A diagnosis of subdural hematoma and adhesive arachnoiditis was made. Her symptoms partially resolved in the following months.

Conclusion

It may be prudent to reconsider the use of repeated AEBP and to avoid the interspace of UDP. A thorough evaluation is warranted to exclude treatable lesions when adverse effects occur.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Unintentional dural puncture (UDP) by epidural needle complicates the care of 1.5% of obstetric patients; post-dural-puncture headache (PDPH) is a common complication [1]. Rapid treatment for PDPH is indicated in the obstetric population because severe symptoms can prevent mother-neonate interactions [2]. Treatment options include autologous epidural blood patch (AEBP), in which blood is injected into the epidural space; this may alleviate symptoms by causing continued tamponade [3], adhering to the dural sac for an extended period of time at extended vertebral levels [4, 5], thereby restoring intracranial pressure and reducing cerebral vasodilation. Multiple courses of AEBP may be necessary [6,7,8,9].

Rare, severe neurological complications of AEBP have been reported [9], in addition to common issues, including post-procedural pain in the low back, buttock, or leg [9]. Inadvertent injection of blood into the subarachnoid space may result in subdural hematoma and adhesive arachnoiditis, which may lead to permanent nerve damage [10]. Subdural blood causes adhesive arachnoiditis by releasing free radicals, which inflame pia and arachnoid mater, causing localized fibrosis [11]. In AEBP, blood may enter the subdural space by direct injection or through another dural hole caused by multiple attempts to locate the epidural space [12]. These conditions can be suspected clinically and identified by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [10]. Early diagnosis is important because these conditions may mimic others that require expedited interventions, including abscess formation [13].

We present a case of subacute subdural hematoma and adhesive arachnoiditis following two courses of AEBP, one of which was performed at the interspace of UDP. This condition was diagnosed clinically and identified using MRI.

Case presentation

A 40-year-old Japanese primigravida with American Society of Anesthesiologists Performance Status 1 was scheduled for an elective cesarean section because of a low-lying placenta at 38 weeks of gestation. Her past, pertinent medical history was unremarkable. Combined spinal-epidural anesthesia (CSEA) was planned for the surgery. The patient was placed in a right lateral recumbent position. Eighty-three percent alcohol with 0.5% chlorhexidine was used for skin preparation. A 16-gauge CSEcure® needle (Smiths Medical Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted at the L2–3 interspace. Loss of resistance to saline was noted at 3.3 cm using a median approach. A 27-gauge pencil point needle was introduced by 5 mm. On advancing the spinal needle, the patient experienced radiating pain in her right leg, which, unfortunately, caused her to move. At this time, we identified UDP with a constant stream of clear cerebrospinal fluid. The epidural needle was immediately removed. CSEA was again performed at the L3–4 interspace using an identical 16-gauge needle, with a loss of resistance to saline at 3.0 cm followed by an uneventful needle-through-needle spinal tap. We injected 8 mg of hyperbaric bupivacaine and 20 μg of fentanyl intrathecally, and placed a 17-gauge Perifix® catheter (B Braun, Tokyo, Japan) epidurally. There were no signs of CSF backflow nor blood backflow through the needle or the catheter. CSEA resulted in an inadequate block at the level of Th12. A decision was made to perform supplemental epidural anesthesia at the Th12-L1 interspace using a 17-gauge Uniever® needle (Unisys, Tokyo) with 6 mL of epidural 0.75% ropivacaine, which yielded adequate anesthesia for the operation, without complications. The remainder of the delivery was uneventful.

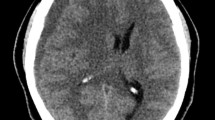

Eighteen hours after delivery, the patient reported postural headache and stiff neck, consistent with PDPH. Her symptoms were refractory to conservative management, such as intravenous hydration and bed rest, as well as oral loxoprofen sodium. An AEBP was performed approximately 44 h after delivery using 20 mL of autologous blood injected at the L3–4 interspace with a median approach using a 17-gauge Tuohy needle. Back pain or neurologic symptoms were not noticed at this time. Symptoms transiently disappeared, but recurred 2 days later. Five days after delivery, a repeat AEBP was performed with 20 mL of autologous blood at the L2–3 interspace, where the UDP had occurred, using a paramedian approach. These procedures were performed by the most experienced anesthesiologists available, using loss-of-resistance to saline technique without difficulty. Blood was obtained using 10% povidone iodine skin preparation for each procedure. During the second AEBP, the patient reported pain in the back, buttocks, and posterior aspect of the lower extremities, as well as bilateral S1 radicular pain. Following the second AEBP, PDPH quickly resolved, but severe and transient symptoms were observed. The patient was unable to extend her legs beyond 135° due to radiating pain. No dysuria was present. MRI demonstrated intrathecally extending subdural hematoma around an aggregated cauda equina from L3 to L4 and another similar lesion at the L5 vertebral level (Figs. 1 and 2). No signs of epidural hematoma or infection were identified. Subdural hematoma and adhesive arachnoiditis were diagnosed and oral analgesic therapy was continued. Eight days later, a repeat MRI examination demonstrated partial improvements. One month after delivery, her residual neurologic symptoms included occasional discomfort in the right posterior thigh. The patient decided to request further evaluation only if symptoms were to worsen and declined further radiologic studies at the time.

An axial gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted image at the level of L5 and a T2-weighted image at the same level. These images show clumpy cauda equina fibers within dura mater. White arrow indicates a cauda equina aggregated posteriorly, with identifiable blood in a white dot. The clumped, asymmetric appearance of cauda equina fibers and contrast enhancement indicates the existence of inflammation

Discussion

We present a case of subacute subdural hematoma and arachnoiditis following two AEBP courses. Following the first uneventful treatment one interspace below, the repeat procedure at the interspace of UDP resulted in neurologic sequelae. We suspect that the blood pervaded through the preexisting dural hole into the subdural space. We reached this diagnosis with early neurologic examination and MRI, excluding possibilities of other treatable complications. Although this case involved an obstetric patient, the complication can happen in any patient who undergoes AEBP.

PDPH with epidural needles is reported to last at least 4–6 days without successful treatment [14]. Treatment options include hydration, caffeine, and oral analgesics, all of which are regarded as ineffective, compared to AEBP. In case of post-epidural PDPH in the obstetric population, complete and permanent relief with a single course of AEBP occurs in approximately 30% of patients [14]. Among patients who have undergone one failed AEBP, a similar success rate is expected for repeated treatment [14, 15].

It is unclear whether one failed AEBP should prompt repeated AEBP. The pierced dura eventually heals with fibrin deposition [16]. Additionally, following blood injection, the epidural space may become inflamed [17], making repeated interventions more difficult and potentially prone to complications; there are three reports of severe outcomes following repeated AEBP in an obstetric context [18,19,20]. Moreover, PDPH can become complicated by a headache of a different origin (e.g., psychological, vascular, or musculoskeletal) [21]; in such cases, AEBP is futile. Risks and benefits of repeated AEBP must be discussed beforehand.

To our knowledge, no study exists regarding the optimal volume of blood used in a repeated AEBP procedure. Moreover, this is unclear for the first AEBP, although a prior study supported injection of 20 mL [22]. In addition, the amount of blood may not significantly impact efficacy [23]. Therefore, we suspect that no rationale exists to inject a volume of blood in excess of 20 mL.

In our case, although the decision to perform repeated AEBP seemed reasonable, blood injection at the interspace of UDP may have been inappropriate. While supporting literature is insufficient [18, 24, 25], performing AEBP at the level of the dural hole may cause subdural blood infusion. No optimal location for AEBP has been established. The preferred method has been an approach at or one interspace below the dural injury, based on an imaging study favoring cephalad blood distribution [4]. Additionally, we found no reports of complicated AEBPs with blood injected below the interspace of UDP in the obstetric population (Table 1). It may be wise to avoid the interspace of UDP unless absolutely necessary.

The scarcity of literature causes difficulty in quantifying severe neurologic outcomes of AEBP. To our knowledge, there are seven case reports of arachnoiditis after a single AEBP in an obstetric setting, with various neurological outcomes [10, 17, 18, 24,25,26,27] (Table 1). Severe outcomes are more likely when a large amount of blood pervades the dura, as indicated by either a larger amount of blood injected [10, 18, 19] or a subdural catheter used as a conduit [26].

In our case, MRI was useful because the clinical diagnosis was challenging. Subdural hematoma and adhesive arachnoiditis, which may be irreversible [19, 26], may mimic treatable complications, including abscess formation [13]. Early diagnosis is important to manage treatable complications promptly and to ensure follow-up. Fortunately, the patient’s condition improved within 1 month after the incident. Further studies are needed to elucidate the nature of these rare complications.

Although uncommon, subacute subdural hematoma and adhesive arachnoiditis can occur after AEBP, with potentially greater likelihood following a repeated procedure and if the procedure is performed on the interspace of UDP. Our case highlights that it is prudent to reconsider and discuss risks and benefits before performing repeated AEBP; it may be important to avoid the interspace of UDP, which may be correlated with severe adverse effects. A thorough neurological evaluation and MRI examination are warranted if a patient experiences persistent low back pain and radiculopathy following AEBP, which suggests subdural hematoma and adhesive arachnoiditis.

Abbreviations

- AEBP:

-

Autologous epidural blood patch

- CSEA:

-

Combined spinal-epidural anesthesia

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PDPH:

-

Post-dural-puncture headache

- UDP:

-

Unintentional dural puncture

References

Choi PT, Galinski SE, Takeuchi L, Lucas S, Tamayo C, Jadad AR. PDPH is a common complication of neuraxial blockade in parturients: a meta-analysis of obstetrical studies. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50:460–9.

Sachs A, Smiley R. Post-dural puncture headache: the worst common complication in obstetric anesthesia. Semin Perinatol. 2014;38:386–94.

Kroin JS, Nagalla SK, Buvanendran A, McCarthy RJ, Tuman KJ, Ivankovich AD. The mechanisms of intracranial pressure modulation by epidural blood and other injectates in a postdural puncture rat model. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:423–9 table of contents.

Beards SC, Jackson A, Griffiths AG, Horsman EL. Magnetic resonance imaging of extradural blood patches: appearances from 30 min to 18 h. Br J Anaesth. 1993;71:182–8.

Griffiths AG, Beards SC, Jackson A, Horsman EL. Visualization of extradural blood patch for post lumbar puncture headache by magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Anaesth. 1993;70:223–5.

Casement BA, Danielson DR. The epidural blood patch: are more than two ever necessary? Anesth Analg. 1984;63:1033–5.

Fry RA, Perera A. Failure of repeated blood patch in the treatment of spinal headache. Anaesthesia. 1989;44:492–3.

Turnbull DK, Shepherd DB. Post-dural puncture headache: pathogenesis, prevention and treatment. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91:718–29.

Gaiser RR. Postdural puncture headache: an evidence-based approach. Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;35:157–67.

Peter Kalina PC, Weingarten T. Intrathecal injection of epidural blood patch: a case report and review of the literature. Emerg Radiol. 2004;11:56–9.

Renck H. Neurological complications of central nerve blocks. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1995;39:859–68.

Tekkok IH, Carter DA, Brinker R. Spinal subdural haematoma as a complication of immediate epidural blood patch. Can J Anaesth. 1996;43:306–9.

Collis RE, Harries SE. A subdural abscess and infected blood patch complicating regional analgesia for labour. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2005;14:246–51.

Sprigge JS, Harper SJ. Accidental dural puncture and post dural puncture headache in obstetric anaesthesia: presentation and management: a 23-year survey in a district general hospital. Anaesthesia. 2007;63:36–43.

Williams EJ, Beaulieu P, Fawcett WJ, Jenkins JG. Efficacy of epidural blood patch in the obstetric population. Int J Obstet Anesth. 1999;8:105–9.

DiGiovanni AJ, Galbert MW, Wahle WM. Epidural injection of autologous blood for postlumbar-puncture headache. II. Additional clinical experiences and laboratory investigation. Anesth Analg. 1972;51:226–32.

Devroe S, Van de Velde M, Demaerel P, Van Calsteren K. Spinal subdural haematoma after an epidural blood patch. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2015;24:288–9.

Riley CA, Spiegel JE. Complications following large-volume epidural blood patches for postdural puncture headache. Lumbar subdural hematoma and arachnoiditis: initial cause or final effect? J Clin Anesth. 2009;21:355–9.

Carlsward C, Darvish B, Tunelli J, Irestedt L. Chronic adhesive arachnoiditis after repeat epidural blood patch. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2015;24:280–3.

Hudman L, Rappai G, Bryden F. Intrathecal haematoma: a rare cause of back pain following epidural blood patch. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2015;24:200.

Abouleish E. Epidural blood patch for the treatment of chronic post-lumbar-puncture cephalgia. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:291–2.

Paech MJ, Doherty DA, Christmas T, Wong CA. The volume of blood for epidural blood patch in obstetrics: a randomized, blinded clinical trial. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:126–33.

Safa-Tisseront V, Thormann F, Malassine P, Henry M, Riou B, Coriat P, Seebacher J. Effectiveness of epidural blood patch in the management of post-dural puncture headache. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:334–9.

Verduzco LA, Atlas SW, Riley ET. Subdural hematoma after an epidural blood patch. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2012;21:189–92.

Roy-Gash F, Engrand N, Lecarpentier E, Bonnet MP. Intrathecal hematoma and arachnoiditis mimicking bacterial meningitis after an epidural blood patch. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2017;32:77–81.

Aldrete JA, Brown TL. Intrathecal hematoma and arachnoiditis after prophylactic blood patch through a catheter. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:233–4.

Oh J, Camann W. Severe, acute meningeal Irriatative reaction after epidural blood patch. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:1139–40.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Editage (https://www.editage.jp/) for English language editing.

Funding

None declared.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed in this study are included in this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KI wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and was responsible for the neuraxial anesthesia in this case. TM and AK performed the perioperative management. KK, ST, KH, TS, and MM proofread the manuscript and offered professional advice. TM and SI supervised and edited the manuscript. YT was the attending anesthesiologist for the case. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Iga, K., Murakoshi, T., Kato, A. et al. Repeat epidural blood patch at the level of unintentional dural puncture and its neurologic complications: a case report. JA Clin Rep 5, 14 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40981-019-0232-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40981-019-0232-3