Abstract

Background

Neuraxial anesthesia is widely used for labor analgesia in the USA, such as epidural, combined spinal–epidural, and dural puncture epidural (DPE). Post-dural puncture headache (PDPH) is a well-known complication of neuraxial anesthesia. However, a rare yet more serious complication is subdural hematomas. Untreated subdural hematomas can result in permanent disability and death, hence the need to better understand their development in the obstetric population receiving DPE.

Case presentation

Case one: A 34-year-old G6P3 female at 39-week gestation received a DPE for labor analgesia and underwent a cesarean section for arrest of descent. On postoperative day two, the patient developed a PDPH but opted for conservative treatment. Ten days post-discharge, the patient presented with a large subacute to chronic subdural hematoma with midline shift. The patient underwent a right fronto-temporal craniectomy, evacuation of subdural hematoma, and placement of a subdural drain. Case two: A 31-year-old G1P0 female at 41-week gestation with a past medical history of a chronic right parietal hemangioma and malaria at 29-week gestation received a DPE for induction of labor. She subsequently underwent a primary cesarean section for failure to progress and persistent category-two fetal heart rate tracing. On postoperative day 11, she experienced a severe non-positional right-sided headache. Imaging revealed a subdural hematoma overlying the right frontal temporal and parietal lobes, which was observed and managed non-operatively. On postoperative day 14, the patient received an epidural blood patch for symptomatic intracranial hypotension.

Conclusion

PDPH, a complication of neuraxial anesthesia, is typically benign and often self-resolves with conservative measures. However, to avoid increased morbidity and mortality, monitoring in patients with PDPH at a higher risk for development of subdural hematomas (especially those with known preexisting intracranial pathologies) is critical for prompt diagnosis. As exemplified by our second case, epidural blood patches continue to be effective and may be considered in patients with symptomatic intracranial hypotension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Neuraxial anesthesia is widely used for labor analgesia in the USA. Techniques such as epidural and combined spinal–epidural have been used in modern obstetric anesthesia practices for years. The dural puncture epidural (DPE) technique has shown to provide better sacral analgesia for patients in labor compared to epidural anesthesia, and with fewer maternal and fetal side effects compared to combined spinal–epidural technique (Chau et al. 2017).

A complication of dural puncture during placement of a neuraxial anesthetic is post-dural puncture headaches (PDPH). It is hypothesized that slow leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) into the epidural space through the dural puncture leads to intracranial hypotension and downward traction on pain-sensitive structures (Morewood 1993). PDPH occurs approximately in 1% of patients receiving an epidural anesthetic, likely due to an accidental dural puncture with the Tuohy needle, and 0.7% in spinal anesthetics (Costa et al. 2019). A meta-analysis showed that there is a 1.5% risk of accidental dural puncture with an epidural insertion, and that more than half of these patients develop a subsequent PDPH (Choi et al. 2003). An epidural blood patch (EBP) remains the most effective treatment for PDPH (Kwak 2017).

However, a rare yet more serious complication of dural puncture during placement of a neuraxial anesthetic is intracranial subdural hematomas (SDH). It is thought that loss of CSF and caudal displacement of the brain causes traction and rupture of the delicate bridging veins, leading to SDH formation (Peralta and Devroe 2017). Moore et al. showed a subdural hematoma rate of 1.5 per 100,000 deliveries, and a rate of 147 per 100,000 deliveries for women with PDPH (Moore et al. 2020). Untreated SDH can result in permanent disability and death, hence the need to better understand the development of SDH in the obstetric population receiving neuraxial analgesia.

We present two cases of subdural hematomas following dural puncture epidural anesthetics seen at Stony Brook University Hospital.

Case presentation

Informed consent was obtained from both patients.

Case presentation 1

A 34-year-old G6P3 female at 39-week gestation with a past medical history of syphilis, treated in this and a prior pregnancy, presented with vaginal bleeding and was admitted for induction of labor. The obstetric anesthesiology team performed a dural puncture epidural for labor analgesia. Due to difficult patient anatomy, epidural placement required two attempts: one from the anesthesiology resident and one from the attending physician. Both attempts were performed at the L3-L4, with a 17-gauge Tuohy needle using loss of resistance (LOR) to air technique. A 25-gauge Pencan needle was then advanced through the Tuohy needle, and the return of clear CSF was confirmed via the Pencan needle. After the spinal needle was removed, a 20-gauge multi-orifice epidural catheter was placed. No CSF was noted to flow freely from the Tuohy needle at any point during the procedure, and aspiration of the epidural catheter was negative for CSF. The patient underwent a primary cesarean section with epidural anesthesia for arrest of descent, complicated by postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine atony requiring pharmacologic intervention with methylergonovine.

On postoperative day (POD) one, the patient began to complain of a non-positional headache. The obstetric anesthesiology team examined the patient and determined that the symptoms were not consistent with a classical post-dural puncture headache and thus recommended conservative management. On POD two, the patient developed a positional headache consistent with a PDPH and conservative management was recommended. On POD three, she continued to have a positional headache, but declined an EBP and opted for further conservative management. The patient was discharged home POD three with instructions to call the labor and delivery unit should her headache symptoms worsen.

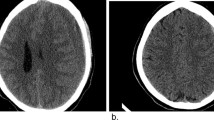

Ten days post-discharge, the patient presented to the emergency department (ED) with a severe, acutely worsening, headache that had been intermittently present since her hospital discharge. A non-contrast CT of the head demonstrated a large right subacute to chronic subdural hematoma with a one centimeter right to left midline shift (Fig. 1). The patient was taken by neurosurgery urgently to the operating room and underwent an uneventful right fronto-temporal craniectomy, evacuation of subdural hematoma, and placement of a subdural drain under general anesthesia. The following day, her subdural drain was removed, and her headache symptoms had resolved. She was discharged home on POD three following her subdural hematoma evacuation.

Five days after discharge home, the patient re-presented to the ED reporting a severe headache. Non-contrast CT head showed no acute changes compared to prior imaging and neurosurgery recommended the patient be discharged upon resolution of symptoms with steroids and outpatient follow-up. On her first outpatient follow-up seven days later, the patient reported no headaches.

Case presentation 2

A 31-year-old G1P0 female at 41-week gestation with a past medical history of a chronic right parietal hemangioma, migraine headaches, and sickle cell trait presented for routine induction of labor. Her pregnancy was complicated by malaria at 29-week gestation treated with artemether–lumefantrine tablets in Nigeria. Of note, she was previously on topiramate for migraine headaches, which was discontinued one year prior by her neurologist. For labor analgesia, she received a DPE using standard equipment at our institution: a 17-gauge Tuohy epidural needle, a 25-gauge Pencan spinal needle, and a 20-gauge epidural catheter, without any complications during placement. She subsequently underwent an uncomplicated primary cesarean section for failure to progress and persistent category-two fetal heart rate tracing. She was evaluated by the anesthesia team on POD one. She denied headaches and was discharged home the following day.

On POD 11, she began to experience a severe right-sided headache that radiated to the right side of her face and was associated with mild photophobia and phonophobia without a positional component or changes in vision. The patient had a similar headache approximately one year prior that resolved after an intravenous infusion of valproate, metoclopramide, and dexamethasone. However, before she was scheduled to receive the same intravenous infusion for her current headache by her neurologist, the patient presented to the ED with acutely worsening headache one day after headache onset. Upon arrival she was hypertensive with systolic blood pressure (SBP) 150–190s mmHg and started on a nicardipine infusion to maintain SBP < 140 mmHg. Imaging revealed a subdural hematoma overlying the right frontal temporal and parietal lobes as well as the right cerebellar tentorium and posterior falx with a maximal thickness of 8–9 mm (Fig. 2). In addition, MRI showed a chronic thrombosis of the right transverse and sigmoid sinuses, which were stable from a previous scan one year prior. In the ED, she reported mild improvement in headache following intravenous fentanyl.

She was admitted to the neurocritical care unit for blood pressure management and frequent neurological checks. The anesthesiology team evaluated her for potential PDPH following DPE; however, patient denied a positional component to her headache. Additionally, she was evaluated by maternal fetal medicine and subsequently treated for postpartum preeclampsia with a magnesium infusion for seizure prophylaxis. On POD 14, the nicardipine infusion was weaned off and she was transitioned to nifedipine and started on aspirin 81 mg. During her hospital stay, she underwent a cerebral angiogram and a repeat CT head which revealed a stable hemangioma and subdural hematoma, respectively. Neurosurgery recommended no acute surgical intervention for the subdural hematoma and an epidural blood patch for symptomatic intracranial hypotension, which she underwent on POD 14. During the procedure, she reported initial worsening of headache after 15 cc of sterile blood was injected into the epidural space, and thus, no further blood was given. Approximately five hours following EBP, the patient was sitting upright and reported mild improvement in symptoms. In the weeks following discharge, she continued to experience non-positional headaches, which mildly improved once she restarted topiramate as per her neurologist’s recommendation. Due to lack of resolution of symptoms, the patient had another CT head, which showed no acute changes compared to the previous imaging.

Discussion

The hypothesized mechanism of development of a subdural hematoma after dural puncture is similar to the proposed mechanism of the development of a PDPH, namely loss of CSF through the dural puncture leading to intracranial hypotension and a caudal shift of the brain (Peralta and Devroe 2017; Macon et al. 1990). This causes stretching of pain-sensitive intracranial structures, leading to a headache and/or tearing of thin bridging veins leading to extravasation of blood and formation of a subdural hematoma (Macon et al. 1990).

Studies have shown that risk factors associated with the formation of SDH following dural puncture are pregnancy, dehydration, multiple lumbar puncture (LP) attempts, large dural hole, use of anticoagulants, cerebral vascular abnormalities, and brain atrophy (Zeidan et al. 2006; Halalmeh et al. 2022). Pregnant patients may be more susceptible to post-dural puncture SDH due to their more frequent use of neuraxial analgesia compared with other patients. Of note, all patients undergoing regional anesthesia are assessed for contraindications including active infection at injection site, coagulopathies, preexisting neurologic deficits, and inability to cooperate (Folino and Mahboobi 2022). Both patients had no contraindications for regional anesthesia. A complete blood count was also obtained and deemed normal prior to placement of these epidural catheters.

Furthermore, in case one, the patient had two dural puncture attempts due to difficult anatomy. Increased dural puncture attempts may increase the size of the dural puncture leading to more rapid CSF leakage into the epidural space. In case two, the patient had a chronic right parietal hemangioma, which may also increase her risk of SDH. Symptoms of PDPH include a localized or global headache with a positional component: worse in the upright position, improved supine. Associated symptoms may include nausea, dizziness, neck pain, visual changes, and tinnitus (Plewa and McAllister 2022). However, when the headache becomes non-postural or is associated with focal neurological deficits such as ptosis, paresis, and/or plegia, then clinical suspicion of SDH must be high (Peralta and Devroe 2017). Dehaene et al. report a case of PDPH quickly evolving into SDH (Dehaene et al. 2021).

EBP is the definitive treatment for patients with PDPH who do not respond to conservative treatment such as rest, oral analgesics, hydration, and caffeine for the first 24–48 h. A study of 504 patients showed that EBP is an effective treatment for severe PDPH, providing symptomatic relief in 93% of patients after one EBP and 97% of patients after a second EBP (Safa-Tisseront et al. 2001). In univariate and multivariate analyses, EBP volume was a strong predictor of EBP efficacy, with EBP volume of 20 cc found to be most efficacious (Shin 2022). One retrospective study also showed EBP efficacy was significantly correlated with < 1.5 years from the headache onset to application, age < 40 years, and CSF opening pressure < 7 cm H2O (Kanno et al. 2020). Contraindications to EBP are patients with coagulation disorders, infection at puncture site, febrile illness, bacteremia, or septicemia (Shin 2022). Relative contraindications include leukemia, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, and platelet count less than 100,000/mm2 (Shin 2022).

In patients with preexisting intracranial pathologies, the decision to perform an EBP is not so straightforward. Rebound intracranial hypertension caused by post-EBP elevation of CSF pressure has been reported in the literature (Kranz et al. 2014). Our patient in case two had a chronic hemangioma and received an EBP with 15 cc of sterile blood. Studies have shown that as little as 15 cc of epidural blood injection can cause an increase in subarachnoid pressures, which may explain her initial worsening of headache (Shin 2022; Shiwlochan et al. 2020). Shiwlochan et al. suggested that injection of a lower volume of blood and at a slower rate can prevent rebound intracranial hypertension, especially in patients with preexisting intracranial pathologies (Shiwlochan et al. 2020). Case two highlights the role of an EBP in patients with intracranial pathologies associated with intracranial hypotension.

Furthermore, there are no clear guidelines as to when to administer an EBP but some studies have suggested increased failure rates in the treatment of PDPH with increased delay in EBP administration (Scavone 2015). In case two, our patient was discharged home after evaluation on POD one, at which point in time she did not experience any headaches. She started developing a severe right-sided headache on POD 11. The decision to administer an EBP to the patient on POD 14 was based on a risk–benefit analysis: The benefits of an EBP in preventing further traction of the intracranial structures outweighed the risks of an EBP. While it is indeed unusual to place an EBP for PDPH two weeks after initial epidural placement, there is some research to suggest EBP may be used to prevent further traction of intracranial structures. Tanweer et al. present cases in which EBP has been used as a therapeutic option for persistent severe intracranial hypotension following clipping of an aneurysm to prevent potentially fatal brain sag (Tanweer et al. 2015).

Conservative management of a PDPH could potentially lead to subdural hematoma formation. Vos et al. proposed that treating a PDPH with an EBP, especially one with increased severity or duration, would decrease the risk of SDH formation (Vos et al. 1991). However, some case reports have shown that one cannot rely on EBP to prevent development of SDH (Davies et al. 2001; Ramírez et al. 2015). Patients with classical PDPH presentations and treated with EBP were still found to have SDH on subsequent neuroimaging, suggesting that EBP does not prevent development of SDH as previously postulated. Davies et al. suggested the use of prophylactic EBP as they suspect the development of a SDH occurs at or near the time of the original puncture (Davies et al. 2001). However, in vitro studies have shown that lidocaine and CSF affect coagulation, causing hypocoagulation and hypercoagulation, respectively, arguing against the usage of prophylactic EBP (Shin 2022). In addition, prophylactic epidural blood patches have not been shown to decrease the incidence of PDPH or the need for therapeutic epidural patch when a prophylactic epidural blood patch was administered to parturients after inadvertent dural puncture (Scavone et al. 2004).

The management of SDH is either conservative or surgical. Early surgical evacuation of acute subdural hematoma in patients with hematoma thickness greater than ten mm or a midline shift greater than five mm on CT scan is associated with better outcomes (Zeidan et al. 2006; Halalmeh et al. 2022). Patients with an acute SDH that is less than ten mm in thickness and has a midline shift of less than five mm can be treated conservatively, with close monitoring of patient’s intracranial pressure and clinical status (Bullock et al. 2006). While management guidelines exist for treatment of acute subdural hematoma, no such guidelines exist for chronic hematoma. However, surgical intervention such as burr hole evacuation or subdural/subgaleal drainage placement for 24–48 h remains the mainstay of treatment in symptomatic patients (i.e., progressive neurologic deficits, decreased level of consciousness) and in those whose neuroimaging demonstrates intracranial compression (Lee 2019; Solou et al. 2022). In case one, the patient had a large right subacute to chronic subdural hematoma with 1cm midline shift. The midline shift greater than five mm warranted urgent neurosurgical intervention. In case 2, the patient had a subdural hematoma with a maximal thickness of 8–9 mm and no midline shift, deeming non-operative management to be appropriate.

Conclusion

PDPH, a complication of neuraxial anesthesia, is typically benign and often self-resolves with conservative measures. However, to avoid increased morbidity and mortality, close monitoring in patients with PDPH at a higher risk for development of subdural hematomas (especially those with known preexisting intracranial pathologies) is critical for prompt diagnosis. As exemplified by our second case, epidural blood patches continue to be effective and may be considered in patients with symptomatic intracranial hypotension.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data have been included. Further information can be requested from the author.

Abbreviations

- DPE:

-

Dural puncture epidural

- PDPH:

-

Post-dural puncture headache

- CSF:

-

Cerebral spinal fluid

- EBP:

-

Epidural blood patch

- SDH:

-

Subdural hematoma

- LOR:

-

Loss of resistance

- POD:

-

Postoperative day

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- CT:

-

Computerized tomography

- LP:

-

Lumbar puncture

References

Bullock MR, Chesnut R, Ghajar J, Gordon D, Hartl R, Newell DW et al (2006) Surgical management of acute subdural hematomas. Neurosurgery 58(3 Suppl):S16-24 (discussion Si-iv)

Chau A, Bibbo C, Huang CC, Elterman KG, Cappiello EC, Robinson JN et al (2017) Dural puncture epidural technique improves labor analgesia quality with fewer side effects compared with epidural and combined spinal epidural techniques: a randomized clinical trial. Anesth Analg 124(2):560–569

Choi PT, Galinski SE, Takeuchi L, Lucas S, Tamayo C, Jadad AR (2003) PDPH is a common complication of neuraxial blockade in parturients: a meta-analysis of obstetrical studies. Can J Anaesth 50(5):460–469

Costa AC, Satalich JR, Al-Bizri E, Shodhan S, Romeiser JL, Adsumelli R et al (2019) A ten-year retrospective study of post-dural puncture headache in 32,655 obstetric patients. Can J Anaesth 66(12):1464–1471

Davies JM, Murphy A, Smith M, O’Sullivan G (2001) Subdural haematoma after dural puncture headache treated by epidural blood patch. BJA Br J Anaesth 86(5):720–723

Dehaene S, Biesemans J, Van Boxem K, Vidts W, Sterken J, Van Zundert J (2021) Post-dural puncture headache evolving to a subdural hematoma: a case report. Pain Pract 21(1):83–87

Folino TB, Mahboobi SK (2022) Regional anesthetic blocks. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. [Cited 7 Feb 2023]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563238/

Halalmeh DR, Sandio A, Adrian M, Moisi MD (2022) Intracranial subdural hematoma versus postdural puncture headache following epidural anesthesia: a case report. Cureus 14(2):e21824

Kanno H, Yoshizumi T, Nakazato N, Shinonaga M (2020) Predictors of the response to an epidural blood patch in patients with spinal leakage of cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Neurol 16(1):1–8

Kranz PG, Amrhein TJ, Gray L (2014) Rebound intracranial hypertension: a complication of epidural blood patching for intracranial hypotension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 35(6):1237–1240

Kwak KH (2017) Postdural puncture headache. Korean J Anesthesiol 70(2):136–143

Lee KS (2019) How to treat chronic subdural hematoma? Past and now. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 62(2):144–152

Macon ME, Armstrong L, Brown EM (1990) Subdural hematoma following spinal anesthesia. Anesthesiology 72(2):380

Moore AR, Wieczorek PM, Carvalho JCA (2020) Association between post-dural puncture headache after neuraxial anesthesia in childbirth and intracranial subdural hematoma. JAMA Neurol 77(1):65–72

Morewood GH (1993) A rational approach to the cause, prevention and treatment of postdural puncture headache. CMAJ 149(8):1087–1093

Peralta F, Devroe S (2017) Any news on the postdural puncture headache front? Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 31(1):35–47

Plewa MC, McAllister RK (2022) Postdural puncture headache. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. [Cited 21 Apr 2022]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430925/

Ramírez S, Gredilla E, Martínez B, Gilsanz F (2015) Bilateral subdural hematoma secondary to accidental dural puncture. Braz J Anesthesiol (english Edition) 65(4):306–309

Safa-Tisseront V, Thormann F, Malassiné P, Henry M, Riou B, Coriat P et al (2001) Effectiveness of epidural blood patch in the management of post-dural puncture headache. Anesthesiology 95(2):334–339

Scavone BM (2015) Timing of epidural blood patch: clearing up the confusion. Anaesthesia 70(2):119–121

Scavone BM, Wong CA, Sullivan JT, Yaghmour E, Sherwani SS, McCarthy RJ (2004) Efficacy of a prophylactic epidural blood patch in preventing post dural puncture headache in parturients after inadvertent dural puncture. Anesthesiology 101(6):1422–1427

Shin HY (2022) Recent update on epidural blood patch. Anesth Pain Med 17(1):12–23

Shiwlochan D, Ohanyan S, Rajput K (2020) It is just a blood patch: considerations for patients with preexisting intracranial hypertension. Case Rep Anesthesiol 2020:e8365296

Solou M, Ydreos I, Gavra M, Papadopoulos EK, Banos S, Boviatsis EJ et al (2022) Controversies in the surgical treatment of chronic subdural hematoma: a systematic scoping review. Diagnostics (basel) 12(9):2060

Tanweer O, Kalhorn SP, Snell JT, Wilson TA, Lieber BA, Agarwal N et al (2015) Epidural blood patch performed for severe intracranial hypotension following lumbar cerebrospinal fluid drainage for intracranial aneurysm surgery. Retrospective series and literature review. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg 17(4):318–323

Vos PE, de Boer WA, Wurzer JAL, van Gijn J (1991) Subdural hematoma after lumbar puncture: two case reports and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 93(2):127–132

Zeidan A, Farhat O, Maaliki H, Baraka A (2006) Does postdural puncture headache left untreated lead to subdural hematoma? Case report and review of the literature. Int J Obstet Anesth 15(1):50–58

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patients depicted here.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WC contributed to literature review and drafting of manuscript. SA was involved in data collecting and drafting of manuscript. LB contributed to data collecting and drafting of manuscript. JS was involved in revising manuscript. SB contributed to revising manuscript. AC was involved in revising manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from both patients.

Consent for publication

Written consent was obtained from both patients. Consent was obtained for oral and written medical information, for the purpose of research publications.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chou, W., Alam, S., Bracero, L. et al. Subdural hematoma following dural puncture epidural anesthesia for labor analgesia: two case reports. Bull Natl Res Cent 47, 40 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-023-01014-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-023-01014-z