Abstract

This study investigated the Performance-Based Assessment (PBA) impact on academic resilience (AR), motivation, teacher support (TS), and personal best goals (PBGs) in different learning environments, specifically online classes and traditional physical classrooms. The research involved 84 participants divided into experimental (online classes, N = 41), and control (physical classes, N = 43) groups. Questionnaires were administered before and after the treatment to assess the participants’ AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs. The data were analyzed using Chi-square tests, revealing significant differences in AR, motivation, and PBGs between the two groups after the treatment. Online classes were found to enhance AR, motivation, PBGs, and acknowledgment of TS compared to the physical environment. These results suggest that PBA can have a positive impact on students’ psychosocial variables and shed light on the potential benefits of online learning environments. The implications of the study are discussed, and suggestions for further research are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A performance-based exam refers to an assessment in which candidates' proficiency in executing specific tasks, typically associated with job or educational prerequisites, is evaluated (Davies et al., 1999). In the evaluation of second languages, activities are made to allow applicants to perform in ways that allow them to show the kinds of language abilities that could be needed in a real-world setting. An overseas-trained doctor might take part in a job-specific role play with a “patient” interviewer, or a test applicant whose language is being assessed for admission to an English-speaking institution or college would be asked to compose a brief academic essay. These types of evaluations are increasingly employed in educational environments to assess language learning gains throughout a teaching period and in specific workplace language evaluations.

PBA is an evaluation approach that incorporates a problem-solving process as part of its testing methodology (Messick, 1994; Torrance, 1995). PBA necessitates students to carry out a task, such as crafting a product or responding to a question, under the premise that specific, quantifiable attributes can be derived from the task's outcome to gauge the degree of students' progress in acquiring the targeted skill or knowledge (Gresse Von Wangenheim et al., 2021; Salma & Prastikawati, 2021; Xing et al., 2021). During the performance phase (Zimmerman & Moylan, 2009), it becomes crucial for learners to proficiently evaluate their ongoing performance to decide whether to persist with their current approach or make adjustments (Panadero et al., 2018). Due to the intimate relationship between performance monitoring and strategy selection, PBA can be advantageous in promoting students' assessment of their competencies within an authentic context (Ali & Hanna, 2022; Çakıroglu et al., 2021; Kargar Behbahani & Khademi, 2022; Van der Graaf et al., 2021). PBA has the potential to inspire students' enthusiasm for learning, encourage the expression of their creative abilities, and offer opportunities for them to connect desired outcomes with the management of their learning behavior (Wang & Kim, 2023).

Online teaching environments refer to digital platforms and virtual spaces where educators deliver educational content and facilitate learning interactions through the Internet (Johnson et al., 2023). These environments can encompass various formats, including web-based courses, video conferencing, learning management systems, and other online tools (Johnson et al., 2023). They enable remote access to educational resources, fostering flexible, self-paced, and often asynchronous learning experiences. Online teaching environments may incorporate multimedia elements, discussion forums, quizzes, and collaborative tools to engage learners and provide a rich educational experience. They have gained prominence, especially in distance education and during situations like the COVID-19 pandemic, offering access to a wide range of educational opportunities beyond traditional physical classrooms (Wang, 2023).

In an academic setting, AR is the ability to successfully foresee and respond to difficult conditions (Romano et al., 2021). A learner's cognitive performance and development remain unimpaired despite encountering stressful events and situations in their academic journey, demonstrating a phenomenon of positive psychological development, and a component of psychological capital is associated with adaptation (Zheng et al., 2020). AR is the ability to effectively address challenges in education by reducing the influence of risk factors and bolstering protective factors. As a result of being exposed to various developmental and contextual obstacles in an academic setting, kids can display resourcefulness by leveraging both internal and external resources (Pooley & Cohen, 2010).

According to research, students' motivation directly affects how they learn, how engaged they are, how persistent they are in achieving their goals, and how they approach learning (Chiu, 2021a, 2021b, 2022). Based on the extent to which the objective is independently approved, student motivation for learning can be roughly divided into two types: intrinsic and extrinsic. According to Deci and Ryan (2000), environments that support the three fundamental psychological requirements of autonomy (perceived self-will), competence (perceived efficacy), and relatedness (feeling reciprocity of care with others and community) will promote intrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation that is both intrinsic and autonomous is referred to as “autonomous motivation” and has been shown to have a variety of positive effects on engagement and academic achievement (Taylor et al., 2014), psychological well-being (Bailey & Phillips, 2016), and creativity (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Contrarily, less autonomous extrinsic motivational strategies, commonly referred to as “controlled motivation”, are associated with lower levels of accomplishment, well-being, and academic task persistence (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

According to Federici and Skaalvik (2014), TS comprises the continuing aid and direction teachers give to their pupils in classroom settings. Supportive teachers pay attention to their students when they are in class and help them with their learning challenges (Patra et al., 2022; Pitzer & Skinner, 2017). Teachers who are encouraging can significantly increase their students’ involvement in the classroom (Strati et al., 2017). They noted that children who feel valued and supported by their teachers in the learning process will actively participate in classroom settings. Similar to this, Jia et al. (2020) asserted that students’ participation in class is greatly influenced by the level of assistance they receive from their professors. They claim that students who experience a lot of support in their academic settings are more inclined to put in extra time and effort during class activities.

In the context of education, the concept of PBGs or personal bests was adopted from the world of sports (Ali et al., 2022; Bandura, 1997; Martin, 2006). The core concept behind PBG is rooted in self-evaluation, self-awareness, self-actualization, self-determination, and individuals' perseverance to meet a personalized standard (Ramshe et al., 2019). According to theory, PBG has a strong connection to intrinsic motivation (Bandura, 1997; Deci & Ryan, 2008), self-efficacy abilities (Martin, 2006), academic engagement (Martin & Elliot, 2016), self-esteem (Martin, 2011), and academic well-being (Xu et al., 2022). Jahedizadeh et al. (2021) claim that PBG specifies the short- and long-term goals of pupils. The well-being of the learners is justified when the goals of the students are defined precisely and connected to educational views.

In the ever-evolving landscape of education, the choice between traditional physical classes and virtual learning environments has gained significant prominence. Amid this shift, the application of PBA has emerged as a key consideration. However, a critical gap exists in understanding the practicality of PBA in these distinct settings—actual classes and virtual classes. This research aims to address this gap by investigating AR, motivation, TS, and PBG effects on the efficacy of PBA within these contexts.

While PBA holds promise for evaluating practical skills and fostering authentic learning experiences (Norris et al., 2023), its suitability in both actual and virtual classes remains a complex matter. AR, encompassing the capacity to navigate challenges and sustain cognitive growth amid academic stressors (Romano et al., 2021), plays a pivotal role in shaping students’ responses to PBA. Likewise, students’ motivation, whether intrinsic or extrinsic, influences their engagement, persistence, and approach to learning, potentially varying in effectiveness across the different learning environments (Chiu, 2021a, 2021b, 2022). Moreover, TS, defined by the assistance and guidance provided by educators (Affuso et al., 2023), can significantly impact students’ involvement and participation. The concept of PBG further influences students’ self-evaluation, self-awareness, and self-determined pursuits (Bandura, 1997), which may interact with the assessment modes in unique ways.

Despite the undeniable promise of PBA, this gap in our understanding persists as an enigma within the field of education. It raises profound questions about how this assessment method, designed to mirror real-world skills and problem-solving capabilities, resonates within the dynamic and rapidly evolving landscapes of both traditional classrooms and virtual learning environments. This absence of clarity creates a significant knowledge void that hinders educational stakeholders, including educators, policymakers, and administrators, from making informed decisions regarding the integration of PBA into various learning environments. Furthermore, this gap limits our ability to capitalize on the unique opportunities that both traditional and virtual classrooms offer in nurturing student growth, fostering motivation, providing TS, and helping students set and achieve their PBGs. This study is thus motivated by a compelling need to fill this gap in the literature, unraveling the intricate dynamics of PBA within these diverse educational settings to inform effective pedagogical practices and advance educational policies tailored to meet the needs of twenty-first-century learners.

This study seeks to uncover the intricate interplay between these factors and the mode of instruction—actual classes versus virtual classes—within the framework of PBA. By delving into this multifaceted inquiry, this research aims to offer insights into designing effective strategies that harness the benefits of PBA, promoting enhanced learning outcomes and academic experiences in both traditional and virtual learning settings. Therefore, the following research questions are addressed:

-

1.

What are the distinct effects of distinct environments of PBA on AR?

-

2.

How do actual versus virtual classes affect learners’ motivation?

-

3.

To what extent does TS influence students’ PBA experiences, and how does this support manifest differently in actual and virtual classes?

-

4.

How does PBG influence students’ attitudes toward PBA, and how do these effects vary in actual and virtual class contexts?

This study can hold substantial significance in the realm of education as it addresses a pivotal yet unexplored aspect of modern learning paradigms. The ongoing shift toward virtual learning, coupled with the increasing adoption of PBA, calls for a nuanced understanding of how these elements intersect and influence learning. By investigating the effects on AR, motivation, TS, and PBG, the practicality and outcomes of PBA in both actual and virtual classes, this research offers insight that can guide educators, administrators, and policymakers in optimizing instructional strategies and support systems.

This study presents a novel and highly significant contribution to the field of education. While previous research has examined PBA or individual psychosocial variables like AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs, the distinctive aspect of this study lies in its comprehensive exploration of their interplay within both traditional and virtual learning environments. This novel approach not only fills a critical gap in the literature but also addresses the pressing need to adapt educational practices to the changing landscape of modern learning, which includes the increasing prevalence of virtual classrooms. The study's significance is further underscored by its potential to uncover valuable insights into the dynamics between these variables and the mode of instruction, ultimately guiding educators, administrators, and policymakers in crafting effective strategies that leverage the benefits of PBA to enhance learning outcomes and academic experiences across diverse learning contexts. This research thus could carry substantial implications for the future of education and has the potential to shape the way we approach teaching and assessment in an evolving educational landscape.

Literature review

Theoretical background

Performance-based assessment

PBA and learning, according to Berman (2008), are based on John Dewey's theory of learning, which claims that 'learning by doing' is a method of connecting facts and concepts in the brain. PBA is rooted in social constructivist theory which posits that assessment is seamlessly woven into all teaching and learning processes (Heydarnejad et al., 2022). According to social constructivists, assessment should be created using real-world tasks that include student feedback and self-evaluation (Yan et al., 2022). Therefore, PBA is based on Vygotsky's sociocultural theory, which claims that social contact is essential to the learning process (Heydarnejad et al., 2022). As a result, learning by doing or doing while learning can effectively increase knowledge and skills (Yavuz & Guzel, 2020).

PBA is the evaluation of real, tangible tasks performed by learners, where they apply their knowledge and skills. Students might demonstrate a task, write a report, or give a presentation, for instance. PBA and learning give students the chance to apply their knowledge and abilities in a classroom setting, use higher-order thinking skills, and connect their learning to practical applications (Hollandsworth & Trujillo-Jenks, 2020). PBA assesses both the learning process and its outcome (Maier et al., 2020). In the words of AlKhateeb (2018), the performance task entails presenting project findings, resolving math concerns, performing demonstrations, researching problems, and developing models. PBA strengthens students' efforts to study and develops their capacity for critical thought (Butakor & Ceasar, 2021). PBA gives students the ability to solve problems (Espinosa, 2015) and identifies the strengths and flaws of the way that teaching is delivered (Taale, 2012).

Assessment in undeniably one of the most crucial facets of the learning process. According to Murchan and Shiel (2017), this task asks teachers to gauge, compile, examine, and translate students' abilities to any viewpoints. When students are given tasks that are not necessary or connected to the curriculum, it is unjust. So that they can all be made jointly through PBA (Mauludi, 2022).

According to Zakaria and Amidi (2020), PBA is a type of evaluation that enables students to share their opinions either individually or collectively based on readings they have independently comprehended earlier and that are organized around predetermined topics. It is also backed by the fact that when testing pupils' driving abilities, performance-based testing should be used rather than multiple choice.

Numerous PBA studies have been put into practice, such as the grammar PBA that does not employ multiple choice questions to encourage honesty among the pupils. It involves the following actions: (1) writing a brief diary entry; (2) sending a message; and (3) writing a self-introduction paragraph (4) reading narratives; (5) sharing unexpected moments; (6) brief interviews (Lestari & Azizah, 2021), all of which were conducted in secondary schools in Hongkong. These studies explored the difficulties in conducting PBA (Yan et al., 2022, cited in Mauludi, 2022), research, such as the investigation of mathematical proficiency and self-efficacy through PBA (Ghofour et al., 2021), and efforts to enhance the quality of education by assessing teachers' competence (Efrilia, 2020), highlights the diverse applications of PBA.

Academic resilience

Resilience is the ability to maintain normal growth and produce positive changes despite extreme adversity (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2003). According to Campbell Sills et al. (2006), resilience is a multidimensional construct that is significantly influenced by a variety of factors. Apart from special talents such as active problem-solving, these factors encompass aspects of temperament and personality as well (Campbell Sills et al., 2006). It diminishes learners' concerns about potential school dropout and underperformance as it empowers them with the confidence to embrace challenges and take risks (Azizi et al., 2022; Rojas, 2015). Additionally, it helps students deal with the stress and despair that come with taking language classes (Khadem et al., 2017). It is a dynamic and supportive concept facilitating adaptive responses to surmount obstacles and achieve positive growth. Additionally, Karabiyik (2020) offered proof that seeking help as well as reflecting on one's experiences are crucial for the development of resilience.

AR is the capacity to anticipate challenges and successfully adapt to them in a learning environment (Romano et al., 2021). Stressful events and situations in a student's academic path do not hinder cognitive function and development, which is a phenomenon of positive psychological development and a part of psychological capital connected with adaptation (Zheng et al., 2020). Cassidy (2015) defined AR as the capacity to handle problems effectively when presented with educational challenges by reducing the influence of risk factors and strengthening protective factors. Children can demonstrate resourcefulness by utilizing both internal and external resources as a result of being exposed to a variety of developmental and contextual challenges in an academic setting (Pooley & Cohen, 2010).

According to research by Bernard (2012), AR has a significant role in predicting academic achievement. AR and academic accomplishment among university students are positively connected, according to a study by Li et al. (2018). According to a 2012 study by Kuss and Griffiths, internet addiction is linked to adverse outcomes like subpar academic performance, social isolation, and psychological suffering.

Motivation

A factor that encourages students to increase their skills is motivation (Astuti, 2013). It plays a crucial part in successfully learning a language (Hussain et al., 2020). More specifically, academic motivation (AM) is essential to a student's psychological health and has an impact on their behavior. This idea relates to students' interests in academic subjects, which shape how they behave, how they view learning, and how they respond to challenges (Abdollahi et al., 2022; Koyuncuolu, 2021). Student AM was divided into two categories by Brophy (1983): state motivation and trait motivation. The inclination of a learner toward a specialized subject is captured by state motivation (Guilloteaux & Dörnyei, 2008). According to Csizér and Dörnyei (2005), trait motivation pertains to a learner's general disposition toward the entire learning process. Trad et al. (2014) claim that unlike state motivation, which is dynamic and subject to change, trait motivation is static. Static motivation can be affected by a variety of elements, including the learning environment, the course material, the teachers' personality, and their interactions with the students (Dörnyei, 2020; Hiver & Al-Hoorie, 2020; Kolganov et al., 2022).

The main theory used to explain AM is self-determination theory (SDT), which Deci and Ryan introduced in 1985. Intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation are the three parts of motivation that SDT postulated. Extrinsic motivation refers to the actions taken to obtain a reward or stay away from a penalty. Deci and Ryan (2020) defined three types of extrinsic motivation in this regard: introjected regulation, identified regulation, and integrated regulation. Inherent inspiration and a natural desire to engage in an activity were the sources of intrinsic motivation. Contrarily, amotivation describes the state of not being motivated to learn a skill or participate in the learning process (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Vadivel et al., 2021). Students' AM is influenced by both their intrinsic and extrinsic incentives (Al-Hoorie et al., 2022; Froiland & Oros, 2014). When students are extremely driven, they don't give up and continue to pursue the learning methods with vigor (Martin, 2013). Even in the face of challenges that students may experience while studying, AM protects students (Howard et al., 2021).

Teacher support

Federici and Skaalvik (2014) define TS as the ongoing guidance and assistance teachers provide to their students in learning environments. When students are in class, supportive teachers give attention to them and support them in overcoming their learning obstacles (Patra et al., 2022; Pitzer & Skinner, 2017). Encouragement from teachers has been shown to greatly enhance students' participation in class (Strati et al., 2017). Children will enthusiastically participate in class activities if they believe that their teachers value and support them in their learning. Similar to this, Jia et al. (2020) claimed that the amount of support students receive from their professors has a significant impact on their involvement in class. Accordingly, learners receiving substantial support within their academic environment are more inclined to allocate additional time and effort to engage in classroom activities.

The amount of assistance, direction, and feedback that a particular teacher provides to his or her students inside the classroom is often the focus of the construct of TS (Filak & Sheldon, 2008). There are four main ways that teachers can help their students in the classroom, according to Tennant et al. (2015): “Emotional support”, “appraisal support”, “instrumental support”, and “informational support”. Emotional support has to do with how much instructors care about their students’ personalities. The quantity of both formal and informal feedback that teachers offer to their learners is linked to the second category of TS known as appraisal support (Murray et al., 2016).

The third sort of TS refers to the practical aid that teachers give to their students in the face of obstacles to learning (Federici & Skaalvik, 2014). Finally, informational support refers to the knowledge and suggestions teachers give to aid their students in resolving issues (Guess & McCane-Bowling, 2016). When combined, teachers' emotional, evaluative, instrumental, and informational support for their students may significantly help them be more motivated to learn (Anderman et al., 2011), feel like they belong (Osterman, 2010), and be more engaged (Conner et al., 2014). To put it another way, encouraging teachers can significantly impact how motivated, connected, and engaged students are in their classrooms (Kiefer et al., 2015).

Personal best goals

Achieving goals is also recognized to have an impact on academic success (Elliot, 2005). PBGs, proposed by Martin (2006), are mostly based on goal-setting theory (Locke & Latham, 2002) and are one of the well-known goal theories. According to Burns et al. (2018), PBGs are objectives that a person sets out to surpass their best prior performance. PBGs are produced by two types of goals, referred to as task-specific and situation-specific (Martin, 2006). PBGs therefore include what must be accomplished explicitly (i.e., task-specific) and why it must be accomplished (i.e., situation-specific). Task-specific goals are further broken down into specificity and challenge. Specificity refers to PBGs being so clear and precise that there is no doubt as to what is anticipated to be gained. The difficulty level associated with PBGs is typically equal to or greater than the individual's previous best performance, as the difficulty level varies among different goals. Specificity and difficulty interact in a way that makes achieving specified and challenging goals more effective (Liem et al., 2012). A person's prior performance is tied to situation-specific goals, which include self-improvement and competitive self-reference (Martin, 2006). Goals with a competitive self-reference focus on competing with oneself rather than with other students in the class. Self-improvement also refers to improving upon prior work. As they are linked to academic progress, engagement, and buoyancy (Burns et al., 2018; Collie et al., 2016; Martin & Elliot, 2016), PBGs play a noteworthy role in academic contexts. Therefore, PBGs give students in educational environments the chance to realize their potential and succeed by overcoming obstacles and developing themselves (Martin, 2006).

Experimental background

Academic resilience

Bernard (2012) found that AR significantly influences the prediction of academic success. According to a study by Li et al. (2018), AR and academic success are positively correlated among university students. Kuss and Griffiths (2012) established a correlation between internet addiction and adverse outcomes such as subpar academic performance, social isolation, and psychological distress.

Kim and Kim (2017) investigated the underlying causes of learners' resilience and how they relate to their drive for learning and language competency. The study found a strong correlation between learners' motivating behavior and persistence, which is a component of resilience. Paul et al. (2014) found a link between various variables of academic motivation and resilience among 200 college students as part of their study on resilience, academic motivation, and social support. Additionally, Gizir and Aydin (cited in Yadgir Basir & Kolahi, 2022) found that among the external protective factors are elevated expectations at home, nurturing relationships within the school environment, and high expectations from peers. Meanwhile, internal factors that have been identified as influencing AR include positive self-perceptions regarding one's academic abilities, lofty educational aspirations, empathetic understanding, an internal locus of control, and a hopeful outlook for the future.

Motivation

Numerous studies have been done on motivation and AM. For instance, Peng (2021) discovered that EFL teachers' communicative styles helped promote AM and involvement in their students. Koné (2021) demonstrated in a different study that the success of the PBA project was significantly influenced by the motivational and emotional states of the learners. In a related investigation, Arias et al. (2022) looked at the connection between emotional intelligence and AM and how they affect students' well-being. Their results confirmed that these two variables had a significant association. From a different angle, Cao (2022) talked about how learners' willingness to speak in a second language is mediated by AM and L2 enjoyment.

Teacher support

Numerous studies have been conducted to examine the impact of TS on students' classroom behaviors because of the critical role it plays in educational settings (Anderman et al., 2011; Conner et al., 2014). To assess TS's effects on students' academic efforts, Dietrich et al. (2015) conducted a study on the topic. Two reliable questionnaires were distributed to 1155 German students to gather their opinions on TS's effect on students' academic efforts. According to data research, student effort in the classroom was thought to be greatly influenced by TS.

Additionally, Feng et al. (2019) examined the impact of TS on Chinese students' educational efforts in a study that is comparable to this one. To do this, 666 Chinese students were given two trustworthy measurements of TS and student academic effort. The findings of structural equation modeling suggested that student academic attempts can be considerably impacted by TS. Similarly, Sadoughi and Hejazi (2021) investigated the role of TS in predicting academic engagement among Iranian students. To do this, 435 EFL students were chosen using multi-stage cluster sampling and asked to complete two trustworthy questionnaires. The examination of the data revealed that Iranian students' academic participation in EFL classrooms can be significantly influenced by TS.

Personal best goals

Despite a growing body of research on learning engagement, little has been written about how it relates to flourishing, and even less has been said about the importance of personal best goals for university students. To close these gaps, Awang and Mahudin (2023) looked at the connection between learning engagement and flourishing by looking at the mediation function of personal best goals. An online survey was used to gather information from a sample of 206 university students from different Malaysian higher education institutions. The findings revealed that flourishing is strongly correlated with both personal best goals and learning engagement, while personal best goals are positively correlated with flourishing. Personal best goals and flourishing are both important determinants of learning engagement. Additionally, personal best goals served as a mediator in the association between thriving and learning engagement, showing that flourishing significantly influences learning engagement indirectly through personal best goals. These findings emphasize how important it is to set personal best goals as one of the ways that thriving may influence learning engagement. They also provided insight on how to effectively support students' learning in higher education and the possible consequences of thriving and personal best goals.

A variety of elements have a significant impact on effective education and evaluation. Some cognitive, social, and emotional aspects that either directly or indirectly affect students' academic achievement were described in the ever-expanding assessment literature. The potential interactions between the Core of Self-Assessment (CSA), Student Evaluation Apprehension (SEA), PBG, and Self-Efficacy (SE) were left unexplored despite the optimistic literature on assessment. To do this, Ismail and Heydarnejad (2023) set out to develop a model that would reveal the relationship between CSA, SEA, PBG, and SE in higher education. Therefore, 467 Iranian EFL university students at the MA level were given the Core of Self-Assessment Questionnaire (CSAQ), the Student Evaluation Apprehension Scale (SEAS), the Personal Best Goal Scale (PBGS), and the Self-Efficacy Scale (SES). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) findings suggested that CSA and SEA may have an impact on PBG and SE. As a result, EFL university students' goal-setting and sense of efficacy beliefs can improve thanks to learners' investment in CSA and positive SEA.

In brief, the empirical background provides valuable insights into the factors under investigation in this study. It highlights the significance of AR as a predictor of academic success, with findings from Bernard (2012) and Li et al. (2018) showcasing the positive correlation between AR and university students' achievements. Additionally, Kuss and Griffiths (2012) shed light on the potential adverse consequences of internet addiction on academic performance. The relationship between motivation and academic motivation is well-documented, with studies by Peng (2021), Kone (2021), Arias et al. (2022) and Cao (2022) demonstrating how various factors, including TS, emotional intelligence, and learners' willingness to speak in an L2, influence motivation, and subsequently, academic engagement. Furthermore, the significance of TS in shaping students' classroom behaviors, academic efforts, and engagement is underscored through research by Anderman et al. (2011), Conner et al. (2014), Dietrich et al. (2015), Feng et al. (2019), and Sadoughi and Hejazi (2021). Finally, the relationship between PBGs, flourishing, and learning engagement, as explored by Awang and Mahudin (2023), emphasizes the importance of setting up PBGs as a means of thriving and enhancing learning engagement. Additionally, Ismail and Heydarnejad (2023) delved into the unexplored dynamics between CSA, SEA, PBGs, and SE, offering valuable insights into how these factors interact in higher education settings.

Amid the evolving educational landscape, the choice between traditional physical classes and virtual learning environments has highlighted the application of PBA as a critical consideration. However, a notable gap exists in understanding the viability of PBA within these diverse contexts. This study aims to address this gap to see where PBA is more practical and what effect it has on AR, motivation, TS, and PBG.

Methods

Design

The study utilizes a quasi-experimental design with a pretest–posttest comparison group. It investigates the impact of two distinct modes of instruction, online classes and actual classes, on students' AR, motivation, TS, and PBG. The study measures these variables twice, once before the treatment and once after- to assess the changes resulting from the mode of instruction. By utilizing two separate groups and incorporating pretest and posttest measurements, the design allows for a comparison of how the different modes of instruction influence the targeted variables. This approach helps to illuminate potential effects while considering initial differences between the groups. The design aligns with our research questions as it enables an investigation into the effects of two distinct modes of instruction, online and traditional classroom settings, on students' AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs. Secondly, employing pretest and posttest measurements permits a comprehensive assessment of changes in these variables due to the mode of instruction. This design choice is essential as it facilitates the comparison of how each mode of instruction impacts the targeted variables while accounting for any initial differences between the groups. Additionally, the quasi-experimental approach is suitable for this study, considering practical constraints and the inability to implement random assignments in real educational settings. Overall, this design was selected to effectively address the research questions and provide meaningful insights into the impact of different instructional modes on student outcomes.

Participants

The study comprises two intact classes each representing a distinct instructional mode. The experimental group, consisting of 41 participants, engages in online classes, while the control group, comprising 43 students, participates in traditional physical classroom settings. The inclusion criteria for both groups involved students currently enrolled in the respective class formats, ensuring that participants had first-hand experience with either online or physical classroom instruction. The assignment to these groups was based on the students' existing enrollment, with those already participating in online classes forming the experimental group and those attending physical classrooms constituting the control group. These participants have been selected based on their existing enrollment in the respective class formats. This setup enables a direct comparison between the effects of online and physical classroom experiences on the targeted variables of AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs. The participants' unique characteristics within their assigned groups contribute to an in-depth exploration of how the mode of instruction influences these crucial dimensions of learning.

Instruments

The study employs a set of well-established instruments to measure various dimensions of the participants' experiences. AR is gauged using the AR Scale-30 (ARS-30), a validated tool developed by Cassidy (2016), designed to assess students' ability to effectively navigate challenges within an academic environment. To evaluate participants' motivation, the Science Motivation Questionnaire II (SMQ-II) is utilized, providing insights into their motivation. TS is assessed using the TS Scale (TTS) developed by Metheny et al. (2008), which measures the extent of supportive interactions between teachers and students in the learning process. Furthermore, participants' PBGs are explored through the PBG scale devised by Martin (2006), delving into their goal-setting behaviors and self-determined pursuits. The incorporation of these instruments ensures a comprehensive examination of AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs, facilitating a thorough analysis of the objectives within the context of distinct instructional modes. As the designers of these scales point to the reliability of validity of their scales, these instrument choices ensure the reliability and validity of measurements, allowing for a comprehensive examination of AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs within the context of distinct instructional modes.

Data collection procedures

The data collection procedures involved administering a set of questionnaires to participants in both conditions to gather insights into their AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs. In the experimental group, before the treatment, 8 learners expressed motivation, 10 reported receiving TS, 7 demonstrated AR, and 9 indicated having PBGs on the pretest. Following the treatment, the posttest results showed significant changes, with 29 learners displaying AR, 24 acknowledging TS, 34 demonstrating motivation, and 35 expressing PBGs. Similarly, in the control group, the pretest results indicated that 10 learners were resilient, 8 received TS, 11 were motivated, and 8 had PBGs. After the treatment, the posttest revealed a shift, with 16 learners exhibiting AR, 17 acknowledging TS, 20 demonstrating motivation, and 26 expressing PBGs.

In both classroom settings, PBA was integrated into the learning process to measure students' skills and competencies within authentic contexts. In online classes, PBA was facilitated through digital platforms and virtual simulations. This allowed students to engage in tasks that mirrored real-world scenarios, such as role plays, presentations, and problem-solving exercises. In actual classroom settings, PBA was conducted through in-person activities, including group discussions, hands-on projects, and interactive presentations. Both approaches aimed to evaluate students' practical abilities and critical thinking skills while aligning with the respective learning environments. This study's design enables a comprehensive exploration of how these diverse instructional modes influenced students' AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs, shedding light on the intricate interplay between pedagogical approaches and students' experiences.

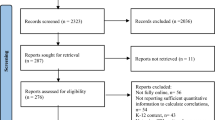

Data analysis procedures

The collected data underwent a rigorous process of analysis to uncover meaningful insights into the effects of PBA in distinct environments. To study the categorical variables' association, a chi-square test for group independence was employed to examine the relationships among variables such as AR, TS, motivation, and PBGs both before and after the treatment within the experimental and control groups. This statistical approach allowed for the determination of significant differences in the distribution of characteristics across different conditions. Before conducting the chi-square tests, crosstabulations and descriptive analyses were performed to provide a comprehensive overview of the distribution of characteristics within each group and condition. This approach facilitates a thorough exploration of the data, enabling the identification of patterns and trends that contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the research outcomes.

Results

The effects of distinct environments of PBA on AR

A chi-square was employed to examine the impact of PBA on AR before and after the treatment due to its suitability for assessing associations between categorical variables. By comparing the distribution of AR levels within the groups before and after the treatment, this statistical test allowed for a thorough investigation of any significant changes or relationships. It enabled us to determine whether the treatment, involving PBA, had a measurable effect on the distribution of AR among the participants. Chi-square analysis, served as a valuable tool to discern any statistically significant differences and shed light on the potential influence of PBA on students' AR within each group.

Table 1 shows that on the pretest, 7 experimental and 10 control subjects were resilient, while the rest were non-resilient learners.

Table 2 shows that at 1 degree of freedom, group differences were not significant on the pretest (df = 1, p > 0.05).

Table 3 shows that on the posttest there were 29 resilient learners in the experimental and 16 ones in the control condition.

Table 4 shows that at 1 degree of freedom, the difference between the groups was significant on the posttest (df = 1, p < 0.05). The effect size was moderate (Phi Cramer's V = 0.336). Hence, online classes made learners more resilient.

The effects of actual and online PBA classes on learners' motivation

A chi-square was employed to examine the impact of PBA on motivation before and after the treatment due to its suitability for assessing associations between categorical variables. By comparing the distribution of AR levels within the groups before and after the treatment, this statistical test allowed for a thorough investigation of any significant changes or relationships. It enabled us to determine whether the treatment involving PBA had a measurable effect on the distribution of motivation among the participants. Chi-square analysis, served as a valuable tool to discern any statistically significant differences and shed light on the potential influence of PBA on students' motivation within each group.

Table 5 shows that on the pretest, only 8 experimental learners and 11 control ones were motivated.

Table 6 reveals that at 1 degree of freedom, the two groups' difference in terms of motivation at baseline was insignificant (df = 1, p > 0.05).

Based on the Table 7, on the posttest 34 experimental learners and 20 control participants were motivated and the rest were unmotivated learners.

Table 8 demonstrates that on the posttest, at 1 degree of freedom, both groups difference was significant (df = 1, p < 0.05). Additionally, the effect size was moderate (Phi Cramer's V = 0.38). Hence, online classes made learners more motivated than actual physical classes.

The effect of PBA on TS experiences in online and actual classes

A chi-square was employed to examine the impact of PBA on TS experienced by learners before and after the treatment due to its suitability for assessing associations between categorical variables. By comparing the distribution of TS levels within the groups before and after the treatment, this statistical test allowed for a thorough investigation of any significant changes or relationships. It enabled us to determine whether the treatment involving PBA had a measurable effect on the distribution of TS among the participants. Chi-square analysis, served as a valuable tool to discern any statistically significant differences and shed light on the potential influence of PBA on students' perceived TS within each group.

Based on Table 9, only 10 experimental subjects and 8 control ones declared that they had experienced TS on the pretest.

Table 10 reveals that at 1 degree of freedom, the two groups' difference in terms of TS declaration at baseline was insignificant (df = 1, p > 0.05).

Table 11 indicates that on the posttest, 24 experimental participants and 17 control learners expressed that they received TS.

Table 12 demonstrates that on the posttest, at 1 degree of freedom, both groups difference was significant (df = 1, p < 0.05). Additionally, the effect size was small (Phi Cramer's V = 0.19). Hence, online classes made learners more motivated than actual physical classes.

The effect of PBA on learners' PBGs in physical and virtual environments

A chi-square was employed to examine the impact of PBA on learners' PBGs before and after the treatment due to its suitability for assessing associations between categorical variables. By comparing the distribution of PBG levels within the groups before and after the treatment, this statistical test allowed for a thorough investigation of any significant changes or relationships. It enabled us to determine whether the treatment involving PBA had a measurable effect on the distribution of PBGs among the participants. Chi-square analysis, served as a valuable tool to discern any statistically significant differences and shed light on the potential influence of PBA on students' perceived PBGs within each group.

According to Table 13, merely 9 experimental and 8 control participants expressed that they had their PBGs set on the pretest.

Table 14 reveals that at 1 degree of freedom, the two groups' difference in terms of PBG declaration at baseline was insignificant (df = 1, p > 0.05).

On the posttest, 35 experimental subjects and 26 control participants expressed that they had their PBGs set in response to the PBA offered (Table 15).

Table 16 demonstrates that on the posttest, at 1 degree of freedom, both groups difference was significant (df = 1, p < 0.05). Additionally, the effect size was almost moderate (Phi Cramer's V = 0.279). Hence, online classes made learners more motivated than actual physical classes.

To sum up, the study employed chi-square analysis to investigate the effects of PBA on AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs before and after the treatment in both online and physical classes. In the case of AR, the pretest showed no significant difference between groups, but the posttest revealed that online classes significantly increased learners' resilience. Similarly, for motivation, no significant difference was observed at baseline, but the posttest indicated that online classes significantly enhanced motivation. In terms of TS, there was no significant difference between groups on the pretest, but on the posttest, online classes had a small yet statistically significant effect, making learners feel more supported. Lastly, regarding PBGs, there was no significant difference between groups on the pretest, but the posttest demonstrated a moderate effect, with online classes leading to more learners setting PBGs. Therefore, online classes were found to positively influence all of these variables compared to physical classes after the implementation of PBA.

Discussion

This study delved into the effects of PBA in distinct learning environments on AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs. Chi-square tests were employed to assess these categorical variables before and after the treatment, allowing for an in-depth exploration of significant changes. The findings indicate that online classes significantly increased learners' resilience (p < 0.05, Cramer's V = 0.336) and motivation (p < 0.05, Cramer's V = 0.38) compared to traditional physical classes. Additionally, online classes also positively impacted learners' experiences of TS (p < 0.05, Cramer's V = 0.19), and setting PBGs (p < 0.05, Cramer's V = 0.279). These results underscore the effectiveness of PBA in enhancing these critical factors within the online learning environment, highlighting the potential advantages of this approach in modern education.

The obtained results can be attributed to several key factors. Firstly, the online learning environment inherently offers certain advantages that may foster higher levels of AR and motivation among learners. Online classes often provide students with greater autonomy and flexibility in managing their learning, allowing them to adapt to challenges and develop resilience more effectively (Cramarenco et al., 2023). The ability to learn at one's own pace and engage with course materials in a self-directed manner can empower students to overcome obstacles and build their resilience.

Moreover, online classes can facilitate a more personalized learning experience, which can significantly impact motivation (Zhao, 2023). Tailored resources, immediate feedback, and interactive online tools can make learning more engaging and relevant for students. This personalization enhances their intrinsic motivation, as they perceive the learning process as more meaningful and enjoyable. Additionally, the absence of geographical constraints in online learning can result in a diverse cohort of students, promoting a sense of community and collaboration that can further boost motivation (Sofi-Karim et al., 2023).

Furthermore, the increase in TS and PBGs observed in the online class setting can be attributed to the adaptability and interactivity of online platforms. Teachers can more easily provide individualized support and feedback in online environments, addressing students' unique needs and fostering a sense of connection. Additionally, online platforms often facilitate goal-setting and tracking, encouraging students to set PBGs and monitor their progress more effectively (Adedoyin & Soykan, 2023). The combination of these factors contributes to the positive outcomes observed in the online class group.

Overall, the results suggest that the online learning environment, when combined with PBA, can create a conducive atmosphere for the development of AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs. Nonetheless, it is crucial to recognize that these findings may also reflect the specific instructional strategies and support systems implemented in the online class studied.

The results of this study offer valuable insights into the potential of online teaching environments combined with PBA to enhance academic resilience, motivation, TS experiences, and PBGs among students. The significant improvements observed in these key dimensions in the online class group underscore the efficacy of PBA within virtual learning spaces. It reflects the adaptability and interactivity of online platforms in fostering a conducive atmosphere for student development. These findings can inform educators, institutions, and policymakers about the benefits of incorporating PBA into online teaching environments, potentially leading to more effective and engaging educational practices in the future.

The study's findings resonate with SDT, emphasizing how autonomy, competence, and relatedness play vital roles in boosting students' motivation and AR. In online classes, students enjoy greater autonomy, enhancing motivation and resilience. Setting PBGs in response to PBA builds competence and fulfills psychological needs as per SDT. Increased TS in online classes fosters relatedness, further boosting motivation and AR.

Furthermore, the study's results align with goal-setting theory, as PBA encourages students to set and pursue PBGs. This theory posits that challenging goals boost motivation and performance. Online class participants, exposed to PBA, exhibited a significant increase in PBGs, highlighting PBA's role in driving goal-setting. These goals likely fueled motivation and AR as students worked toward achieving these self-determined objectives, emphasizing the importance of goal-setting and PBA in enhancing academic outcomes.

Our study's results align with several aspects of the studies regarding AR while also providing unique insights. Bernard (2012) and Li et al. (2018) both found that AR significantly influences academic success, which is consistent with our findings. We observed a significant increase in AR among students in the online environment after exposure to PBA. This suggests that PBA when implemented in an online learning environment, can contribute positively to AR, which may subsequently impact academic success.

Furthermore, the studies by Kim and Kim (2017), Paul et al. (2014), and Gizir and Aydin (cited in Yadgir Basir & Kolahi, 2022) all emphasized the role of motivation and support as factors contributing to AR. Our study also found a substantial increase in motivation and perceived TS among students in the online environment after the PBA intervention. This suggests that PBA, in online learning has the potential to enhance these key factors associated with AR. The positive impact on motivation and support may have contributed to the observed increase in AR among these students.

However, our results differ from the study by Kuss and Griffiths (2012), which associated internet addiction with negative consequences like poor academic achievement. In our study, students in the online class group showed improvement in AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs after the PBA intervention. These findings suggest that when online learning is structured effectively, it can provide a supportive environment that enhances these important factors, ultimately leading to increased AR.

Our study's findings on motivation align with several of the cited studies, highlighting the importance of motivation and its connection to various aspects of academic performance and well-being. Peng (2021) found that EFL teachers' communicative styles positively impacted AM among students. Similarly, in our study, students in the online class showed a significant increase in motivation after the PBA intervention. This suggests that PBA when integrated into online learning, can enhance students' motivation, consistent with Peng's findings.

Kone's (2021) study emphasized the role of motivation and emotional states in the success of PBA projects. Our results resonate with this, as we observed a substantial increase in motivation among students in the online class following the PBA intervention. This suggests that when PBA is applied in an online learning context, it has the potential to positively influence learners' motivational and emotional states, which can contribute to project success.

Arias et al. (2022) explored the connection between emotional intelligence, AM, and students' well-being. Our findings align with the results, as we also observed an increase in motivation among students in the online class group after the PBA intervention. While we didn't measure emotional intelligence, the increase in motivation may indirectly contribute to students' overall well-being, supporting the idea that motivation and emotional factors are interrelated.

Additionally, Cao (2022) discussed the relationship between learners' willingness to speak in an L2, AM, and language enjoyment. While our study did not focus on language learning, our results indicate an increase in motivation among students in the online environment after the PBA intervention suggesting that PBA, even in a different educational context, can positively influence learners' willingness to engage actively.

Our findings on TS and its impact on academic efforts resonate with the existing body of research on this topic. Anderman et al. (2011) and Conner et al. (2014) have emphasized the critical role of TS in educational settings. Similarly, our study reveals that TS had a significant impact on academic efforts, particularly among the online group after the implementation of PBA. Similarly, Dietrich et al. (2015) conducted a study that assessed the effects of TS on students' academic efforts, aligning with our objectives. We observed that TS had a notable influence on students' academic efforts, with a significant increase noted in the online class group following the PBA intervention.

Sadoughi and Hejazi (2021) explored the role of TS in predicting academic engagement among Iranian students, and their results align with our study's findings. While our study did not specifically measure academic engagement, the increase in academic effort observed among the online group after the PBA intervention suggests a positive relationship between TS and students' engagement in the learning process.

Our findings on the relationship between distinct environments and setting PBGs align the Awang and Mahudin (2023). They found that flourishing is correlated with PBGs and learning engagement, which is consistent our ours. These results highlight the importance of setting PBGs as a means through which thriving can impact learning. In contrast, our study differs from Ismail and Heydarnejad (2023) in several ways. They focused on the relationship between CSA, SEA, PBG, and SE in higher education. While our study also investigated the impact of PBA on PBGs, it did not specifically examine the relationship between CSA, SEA, and SE.

The findings align with SDT (Deci & Ryan, 1985) by showcasing how PBA in online classes can enhance students' motivation and AR. The autonomy offered by online learning can boost motivation, while achieving PBGs demonstrates competence, fulfilling basic psychological needs per SDT. Additionally, the results support goal-setting theory, as setting and achieving PBGs positively influence students' motivation. Together, these theories illuminate how PBA, autonomy, competence, and goal-setting are interlinked factors contributing to students' enhanced motivation, AR, and overall engagement in diverse educational settings.

While this study primarily focused on the effects of PBA and instructional mode, it is crucial to acknowledge that other variables or external factors might have influenced the outcomes observed in the online class group. Factors such as students' prior experiences with online learning, their access to technology and resources, and the specific instructional strategies employed by educators could all potentially contribute to the observed changes. For instance, students with prior positive experiences in online learning environments might have been more motivated and resilient in adapting to PBA in this context. Additionally, the quality of instruction, the level of teacher support, and the alignment of course materials with students' needs could influence motivation and engagement in online classes. Therefore, while PBA and instructional mode are significant factors, future research may consider exploring these potential confounding variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the observed changes in the online class group.

The implications of this study are multifaceted and hold significance for both educators and policymakers. Firstly, the findings underscore the potential of PBA in online learning environments to foster students' AR, motivation, perceived TS, and PBGs. Educators can leverage these insights to design and implement effective online teaching strategies that prioritize autonomy, competence, and goal attainment. Policymakers should consider the integration of PBA methodologies into educational policies to enhance the quality of online education. Moreover, these results emphasize the importance of recognizing the distinct advantages of online classes in promoting student resilience and motivation, offering an evidence-based foundation for future decisions regarding the allocation of educational resources and the development of educational practices. Overall, this study highlights the potential benefits of PBA in online learning and class for further exploration of these strategies to optimize student learning experiences.

Providing educators with appropriate training and support can significantly enhance their ability to implement PBA strategies effectively. Key points include pedagogical competence, technology proficiency, adaptation to online teaching, monitoring and feedback, individualization, support networks, cultural competence, assessment literacy, and research-informed practices. By investigating comprehensive educator training and ongoing professional development, educational institutions can ensure that teachers and well-prepared to harness the potential benefits of PBA in various learning environments, whether online or traditional. Ultimately, this supports improves student outcomes and enhances the overall quality of education.

To harness the benefits of PBA in online teaching, educators can focus on designing interactive and engaging learning activities that align with real-world skills and tasks. They should provide clear rubrics and guidelines for assessment, allowing students to understand expectations and self-assess their progress. Additionally, personalized feedback and support are crucial in an online environment to help students improve continuously. Policy changes that can enhance online education include investments in teacher training for effective online pedagogy, ensuring access to quality technology and resources for all students, and promoting research and development in online learning tools and platforms to create more engaging and effective virtual classrooms. These measures collectively contribute to a more robust and accessible online education landscape.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we delved into PBA effects within different learning environments, comparing online classes to physical classrooms. Our investigation uncovered valuable insights into PBA impact on various critical dimensions of students' educational experiences, including AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs. The results revealed significant differences in how these factors evolved in response to PBA, shedding light on the unique advantages of online learning. Notably, online classes were found to significantly enhance students' AR and motivation compared to traditional classes. This suggests that the flexibility and autonomy offered by online learning platforms can foster greater resilience and motivation among students. Additionally, our findings indicated that PBA positively influenced TS and PBGs among students in both learning environments, with learners experiencing virtual classes outperforming physical environment learners, highlighting the broad applicability and benefits of PBA strategies.

Our study found that online classes significantly enhance students' AR and motivation compared to traditional physical classrooms when PBA is implemented. Additionally, PBA positively influenced students' experiences of TS and PBGs in both learning environments, with online learners generally performing better. These results highlight the advantages of PBA in promoting AR, motivation, perceived TA, and setting PBGs, with implications for optimizing student learning experiences in diverse educational settings.

Nonetheless, it is crucial to recognize the limitations of the research. Firstly, the research focused on a specific context, comparing online classes to physical ones, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other educational settings. Additionally, the study relied primarily on self-reported data from questionnaires, which can introduce response bias and might not comprehensively encapsulate the intricacy of learners' experiences. Despite being subject to personal biases, self-reported data in this study has some strengths. It directly reveals how participants perceive AR, motivation, TS, and PBGs. It is cost-effective for large-scale research, allowing a comprehensive examination across different instructional modes. Self-reporting captures individual experiences and nuances, offering a holistic view of student responses to PBA in actual and online classes. Future research could employ a more diverse range of data collection methods, such as interviews or classroom observations, to provide a richer understanding of the mechanisms at play. Furthermore, while this study examined the immediate effects of PBA, longitudinal research could explore how these effects evolve over time. Lastly, the study did not delve into the specific design and implementation of PBA strategies, leaving room for further investigation into the most effective ways to incorporate PBA into both environments.

In light of these limitations, future research endeavors should consider conducting comparative studies across various educational contexts and age groups to gain a more comprehensive understanding of PBA's effects. Exploring the long-term impact of PBA on students' academic trajectories and career outcomes could provide valuable insights into the sustained benefits of these strategies. Moreover, investigating the nuances of PBA design and implementation, along with examining the role of educator training in optimizing PBA effectiveness, would contribute to the growing body of knowledge in this field. By addressing these limitations and pursuing these avenues for further research, we can continue to refine our understanding of PBA's potential in shaping the future of education.

Availability of data and materials

The authors state that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

- PBA:

-

Performance-based assessment

- AR:

-

Resilience

- TS:

-

Teacher support

- PBGs:

-

Personal best goals

- ARS-30:

-

AR Scale-30

- TTS:

-

TS Scale

References

Abdollahi, A., Vadivel, B., Huy, D. T. N., Opulencia, M. J. C., Van Tuan, P., Abbood, A. A. A., & Bykanova, O. (2022). Psychometric assessment of the Persian translation of the Interpersonal Mindfulness Scale with undergraduate students. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 866816.

Adedoyin, O. B., & Soykan, E. (2023). Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(2), 863–875.

Affuso, G., Zannone, A., Esposito, C., Pannone, M., Miranda, M. C., De Angelis, G., & Bacchini, D. (2023). The effects of teacher support, parental monitoring, motivation and self-efficacy on academic performance over time. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 38(1), 1–23.

Al-Hoorie, A. H., Oga-Baldwin, W. Q., Hiver, P., & Vitta, J. P. (2022). Self-determination mini-theories in second language learning: A systematic review of three decades of research. Language Teaching Research, 9, 13621688221102686.

Ali, A. D., & Hanna, W. K. (2022). Predicting students’ achievement in a hybrid environment through self-regulated learning, log data, and course engagement: A data mining approach. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 60(4), 960–985.

Ali, Z., Palpanadan, S. T., Asad, M. M., Churi, P., & Namaziandost, E. (2022). Reading approaches practiced in EFL classrooms: A narrative review and research agenda. Asian-Pacifc Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-022-00155-4

AlKhateeb, M. A. (2018). The effect of using performance-based assessment strategies to tenth-grade students’ achievement and self-efficacy in Jordan. Journal of Educational Sciences, 13(4), 489–500. https://doi.org/10.18844/cjes.v13i4.2815

Anderman, L., Andrzejewski, C. E., & Allen, J. (2011). How do teachers support students’ motivation and learning in their classrooms? Teachers College Record, 113(5), 969–1003.

Arias, J., Soto-Carballo, J. G., & Pino-Juste, M. R. (2022). Emotional intelligence and academic motivation in primary school students. Psicologia: Refexão e Crítica, 35, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-022-00216-0

Astuti, S. P. (2013). Teachers’ and students’ perception of motivational teaching strategies in an Indonesian high school context. TEFLIN Journal, 24(1), 14–31.

Awang, N. A., & Mahudin, N. D. M. (2023). Flourishing and learning engagement: The importance of personal best goals. International Journal of Education and Training, 9(1), 1–9.

Azizi, Z., Namaziandost, E., & Rezai, A. (2022). Potential of podcasting and blogging in cultivating Iranian advanced EFL learners’ reading comprehension. Heliyon, 8(5), e09473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09473

Bailey, T. H., & Phillips, L. J. (2016). The influence of motivation and adaptation on students’ subjective well-being, meaning in life and academic performance. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(2), 201–216.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman and Company.

Berman, S. (2008). Performance-based learning: Aligning experiential tasks and assessment to increase learning. Corwin Press.

Bernard, N. S. (2012). Academic resilience in the face of challenge: The role of personal psychological resources. Psi Chi Journal of Undergraduate Research, 17(1), 14–19.

Brophy, J. E. (1983). Research on the self-fulfilling prophecy and teacher expectations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(5), 631–661.

Burns, E. C., Martin, A. J., & Collie, R. J. (2018). Adaptability, personal best (PB) goals setting, and gains in students’ academic outcomes: A longitudinal examination from a social cognitive perspective. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 53, 57–72.

Butakor, P. K., & Ceasar, J. (2021). Analysing Ghanaian teachers’ perceived effects of authentic assessment on student performance in Tema Metropolis. International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 13(3), 1946–1966.

Çakıroglu, U., Çevik, I., Koseli, E., & Aydın, M. (2021). Understanding students’ abstractions in block-based programming environments: A performance based evaluation. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 41, 100888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100888

Campbell Sills, L., Cohan, S. L., & Stein, M. (2006). Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behavior Research and Therapy, 44(4), 585–599.

Cao, G. (2022). Toward the favorable consequences of academic motivation and L2 enjoyment for students’ willingness to communicate in the second language (L2WTC). Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 997566. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.997566

Cassidy, S. (2015). Resilience building in students: The role of academic self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1781. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01781

Cassidy, S. (2016). The Academic resilience scale (ARS-30): A new multidimensional construct measure. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1787.

Chiu, T. K. F. (2021a). Digital support for student engagement in blended learning based on self-determination theory. Computers in Human Behavior, 124, 106909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106909

Chiu, T. K. F. (2021). Student engagement in K-12 online learning amid COVID-19: A qualitative approach from a self-determination theory perspective. Interactive Learning Environments. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2021.1926289

Chiu, T. K. F. (2022). Applying the Self-determination Theory (SDT) to explain student engagement in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54, 14–30.

Collie, R. J., Martin, A. J., Papworth, B., & Ginns, P. (2016). Students’ interpersonal relationships, personal best (PB) goals, and academic engagement. Learning and Individual Differences, 45, 65–76.

Conner, A., Singletary, L. M., Smith, R. C., Wagner, P. A., & Francisco, R. T. (2014). Teacher support for collective argumentation: A framework for examining how teachers support students’ engagement in mathematical activities. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 86(3), 401–429.

Cramarenco, R. E., Burcă-Voicu, M. I., & Dabija, D. C. (2023). Student perceptions of online education and digital technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Electronics, 12(2), 319.

Csizér, K., & Dörnyei, Z. (2005). Language learners’ motivational profiles and their motivated learning behavior. Language Learning, 55(4), 613–659.

Davies, A., Brown, A., Elder, C., Hill, K., Lumley, T., & McNamara, T. (1999). Dictionary of language testing. Cambridge University Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Canadian Psychology, 49(1), 14–23.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Dietrich, J., Dicke, A. L., Kracke, B., & Noack, P. (2015). Teacher support and its influence on students’ intrinsic value and effort: Dimensional comparison effects across subjects. Learning and Instruction, 39, 45–54.

Dörnyei, Z. (2020). Innovations and challenges in language learning motivation. Routledge.

Efrilia, E. (2020). Relationship of teacher competency test and teacher performance assessment in increasing education quality. JournalNX, 6(6), 757–766.

Elliot, A. J. (2005). A conceptual history of the achievement goal construct. Handbook of Competence and Motivation, 16(2005), 52–72.

Espinosa, L. F. (2015). Effective use of performance-based assessments to identify English knowledge and skills of EFL students in Ecuador. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 5(12), 2441–2447.

Federici, R. A., & Skaalvik, E. M. (2014). Students’ perceptions of emotional and instrumental teacher support: Relations with motivational and emotional responses. International Education Studies, 7(1), 21–36.

Feng, X., Xie, K., Gong, S., Gao, L., & Cao, Y. (2019). Effects of parental autonomy support and teacher support on middle school students’ homework effort: Homework autonomous motivation as mediator. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 612. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00612

Filak, V. F., & Sheldon, K. M. (2008). Teacher support, student motivation, student need satisfaction, and college teacher course evaluations: Testing a sequential path model. Educational Psychology, 28(6), 711–724.

Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2003). A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist, 18(1), 12–23.

Froiland, J. M., & Oros, E. (2014). Intrinsic motivation, perceived competence and classroom engagement as longitudinal predictors of adolescent reading achievement. Educational Psychology, 34(2), 119–132.

Ghofur, A., Masrukan, M., & Rochmad, R. (2021). Mathematical literacy ability in experiential learning with performance assessment based on self-efficacy. Unnes Journal of Mathematics Education Research, 10(A).

Gresse Von Wangenheim, C., Alves, N. D. C., Rauber, M. F., Hauck, J. C. R., & Yeter, I. H. (2021). A proposal for performance-based assessment of the learning of machine learning concepts and practices in K–12. Informatics in Education, 21(3), 479–500.

Guess, P. E., & McCane-Bowling, S. J. (2016). Teacher support and life satisfaction: An investigation with urban, middle school students. Education and Urban Society, 48(1), 30–47.

Guilloteaux, M. J., & Dörnyei, Z. (2008). Motivating language learners: A classroom-oriented investigation of the effects of motivational strategies on student motivation. TESOL Quarterly, 42, 55–77.

Heydarnejad, T., Tagavipour, F., Patra, I., & Farid Khafaga, A. (2022). The impacts of performance-based assessment on reading comprehension achievement, academic motivation, foreign language anxiety, and students’ self-efficacy. Language Testing in Asia, 12(1), 1–21.

Hiver, P., & Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2020). Reexamining the role of vision in second language motivation: A preregistered conceptual replication of you. Language Learning, 70(1), 48–102.

Hollandsworth, J., & Trujillo-Jenks, L. (2020). Performance-based learning: How it works. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-and-learning/performance-based-learning-how-it-works/

Howard, J. L., Bureau, J., Guay, F., Chong, J. X., & Ryan, R. M. (2021). Student motivation and associated outcomes: A meta-analysis from self-determination theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620966789

Hussain, M. S., Salam, A., & Farid, A. (2020). Students’ motivation in English language learning (ELL): An exploratory study of motivational factors for EFL and ESL adult learners. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 9(4), 15–28.

Jahedizadeh, S., Ghonsooly, B., & Ghanizadeh, A. (2021). A model of language students’ sustained fow, personal best, buoyancy, evaluation apprehension, and academic achievement. Porta Linguarum, 35, 257–275. https://doi.org/10.30827/portalin.v0i35.15755

Johnson, C. C., Walton, J. B., Strickler, L., & Elliott, J. B. (2023). Online teaching in K-12 education in the United States: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 93(3), 353–411.

Jia, M., Zhang, H., & Li, L. (2020). The power of teacher supportive communication: Effects on students’ positive emotions and engagement in learning. Northwest Journal of Communication, 48(1), 9–36.

Karabıyık, C. (2020). Interaction between academic resilience and academic achievement of teacher trainees. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching, 7(4), 1585–1601.

Kargar Behbahani, H., & Khademi, A. (2022). The concurrent contribution of input flooding, visual input enhancement, and consciousness-raising tasks to noticing and intake of present perfect tense. MEXTESOL Journal, 46(4), n4.

Kiefer, S. M., Alley, K. M., & Ellerbrock, C. R. (2015). Teacher and peer support for young adolescents’ motivation, engagement, and school belonging. Rmle Online, 38(8), 1–18.

Kim, T. Y., & Kim, Y. K. (2017). The impact of resilience on L2 learners’ motivated behavior and proficiency in L2 learning. Educational Studies, 43(1).

Khadem, H., Motevalli Haghi, S. A., Ranjbari, T., & Mohammadi, A. (2017). The moderating role of resilience in the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and anxiety and depression symptoms among firefighters. Journal of Practice in Clinical Psychology, 5(2), 133–140.

Kolganov, S. V., Vadivel, B., Treve, M., Kalandarova, D., & Fedorova, N. V. (2022). COVID-19 and two sides of the coin of religiosity. HTS Teologiese Studies/theological Studies, 78(4), 7.

Koné, K. (2021). Exploring the impact of performance-based assessment on Malian EFL learners’ motivation. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 12(3), 51–64.

Koyuncuoğlu, Ö. (2021). An investigation of academic motivation and career decidedness among university students. International Journal of Research in Education and Science (IJRES), 7(1), 125–143.