Abstract

In this study, a multivariate ARMA–GARCH model with fractional generalized hyperbolic innovations exhibiting fat-tail, volatility clustering, and long-range dependence properties is introduced. To define the fractional generalized hyperbolic process, the non-fractional variant is derived by subordinating time-changed Brownian motion to the generalized inverse Gaussian process, and thereafter, the fractional generalized hyperbolic process is obtained using the Volterra kernel. Based on the ARMA–GARCH model with standard normal innovations, the parameters are estimated for the high-frequency returns of six U.S. stocks. Subsequently, the residuals extracted from the estimated ARMA–GARCH parameters are fitted to the fractional and non-fractional generalized hyperbolic processes. The results show that the fractional generalized hyperbolic process performs better in describing the behavior of the residual process of high-frequency returns than the non-fractional processes considered in this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is important to model the dynamic behavior of high-frequency time series returns because they have unique characteristics that are not present in other types of time series data. These distinctive properties are referred to as the three stylized facts in finance: long-range dependence, fat-tail property, and volatility clustering effect. The volatility clustering effect is first noted by Mandelbrot (1963b), where it is submitted that “large changes tend to be followed by large changes, of either sign, and small changes tend to be followed by small changes”. Fama (1970) states that “large price changes are followed by large price changes, but of unpredictable sign”. Mandelbrot (1963b) also observes that asset returns are highly leptokurtic and slightly asymmetric. The autoregressive conditional heteroskedastic (ARCH) model formulated by Engle (1982) and the generalized ARCH (GARCH) model conceptualized by Bollerslev (1986) are the first models introduced to capture the volatility clustering effect and estimate conditional volatility.Footnote 1 The standard forms of the ARCH and GARCH models with normal (Gaussian) innovations successfully capture volatility clustering but sometimes fail to adequately account for conditional leptokurtosis. Hence, a need for more flexible conditional distributions to be explored has arisen. In this sense, much research has tried to account for the fat-tail property found in most financial return data: for example, the Student’s t-distribution (Bollerslev 1987), non-central t-distribution (Harvey and Siddique 1999), generalized hyperbolic skew Student’s t-distribution (Aas and Haff 2006), Johnson’s SU-distribution (Johnson 1949; Yan 2005; Rigby and Stasinopoulos 2005; Choi and Nam 2008; Naguez and Prigent 2017; Naguez 2018), generalized error distribution (GED) (Nelson 1991; Baillie and Bollerslev 2002), and Laplace distribution (Granger and Ding 1995). However, these distributions generally have numerous issues in the applications, even though they may be capable in some cases, and the issues include that a GED distribution does not have a sufficient fat tail to account for extreme events and the density of a non-central t-distribution has the sum of an infinite series.

In addition, during the past decades, there has been growing interest in other types of fat-tail distributions in finance, including a generalized hyperbolic distribution (Barndorff-Nielsen 1977), a normal inverse Gaussian distribution (Barndorff-Nielsen 1995), a variance gamma distribution (Madan and Seneta 1990), a stable distribution (Mandelbrot 1963a; Liu and Brorsen 1995; Panorska et al. 1995; Mittnik et al. 1998; Mittnik and Paolella 2003), and a tempered stable distribution (Rosiński 2007; Kim et al. 2009). In particular, the generalized hyperbolic distribution is a very general form that involves other types of distributions as special cases, such as a Student’s t-distribution, hyperbolic distribution, normal inverse Gaussian distribution, variance gamma distribution, and Laplace distribution (Anderson 2001; Jensen and Lunde 2001; Venter and De Jongh 2002; Forsberg and Bollerslev 2002; Stentoft 2008). Although the aforementioned fat-tail distributions have been studied for empirical innovations in ARMA–GARCH models to capture the fat-tail property on financial return data, Sun et al. (2008) and Beck et al. (2013) evoke that these distributions are unable to fully describe the stylized facts, especially in high-frequency time series analysis.

However, since Mandelbrot and Van Ness (1968) have introduced fractional Brownian motionFootnote 2 to explain short- and long-range dependence, several empirical studies on asset prices (Lo 1991; Cutland et al. 1995; Willinger et al. 1999; Robinson 2003; Casas and Gao 2008; Chronopoulou and Viens 2012; Cont 2005; Mariani et al. 2009; Cheridito 2003; Comte and Renault 1998; Rosenbaum 2008) have investigated the long-range dependence properties of asset returns. In the sense that the fractional Brownian motion can capture the long-range dependence properties, the ARCH and GARCH models with innovations utilizing the fractional Brownian motion can capture not only the long-range dependence but also the volatility clustering effect on high-frequency return data. However, the fat-tail properties remain unconsidered. Hence, in an attempt to better describe high-frequency returns, Sun et al. (2008) offer a univariate model with three stylized facts by taking the ARMA–GARCH model with fractional stable distributed residuals, and they suggest that the model performs effectively in high-frequency returns. In addition, Kim (2012) introduced the fractional multivariate normal tempered stable process as a subclass of the fractional stable processFootnote 3 using time-changed fractional Brownian motion with the fractional tempered stable subordinator. The fractional tempered stable process was redefined by Kim (2015) with the stochastic integral for the Volterra kernel presented in Houdre and Kawai (2006), and it was applied to the innovations on the multivariate ARMA–GARCH modelFootnote 4. In addition, Kozubowski et al. (2006) applied fractional Laplace motion by subordinating fractional Brownian motion to a gamma process to model a financial time series. The fractional normal inverse Gaussian process was proposed in Kumar et al. (2011) and Kumar and Vellaisamy (2012).

Much research has addressed wide issues, especially the simulation and parameter estimations in processes with long-range dependence, as well as the detection of long-range dependence. This study is motivated by the availability of high-frequency time series return data and the need for a new market model accommodating three stylized facts. The main contribution of this study is the development of a general fractional model that incorporates three stylized facts into the volatility process. This is the first study to explore the fractional generalized hyperbolic process and apply it to a multivariate ARMA–GARCH model. The generalized hyperbolic process is derived using time-changed Brownian motion with the generalized inverse Gaussian subordinator. Thereafter, the univariate fractional generalized hyperbolic process is defined by the stochastic integral for the Volterra kernel. The basic properties and covariance structure of the multivariate fractional generalized hyperbolic process are discussed, and a numerical method for generating the sample paths of the processes is presented. Using high-frequency stock return data, parameter estimations on the ARMA–GARCH model with fractional generalized hyperbolic innovations are provided, and goodness-of-fit tests are performed for the estimated parameters to validate the model.

The purpose of this study is threefold. First, a new ARMA–GARCH model that accounts for three stylized facts is presented to provide the broad framework of an alternative model that can be used in financial economic applications. Second, we examine whether considering three stylized facts, especially with a fractional generalized hyperbolic innovation, produces superior forecast estimates and thereby motivates their use in effectively managing financial risk as well as optimizing portfolios in high-frequency time series return data. Finally, this study calls for attention to an assumption underlying the mean-variance model (Markowitz 1952) applied to high-frequency returns, that is, the assumption that asset returns are normally distributed. By being the first to derive a fractional generalized hyperbolic process using time-changed Brownian motion, we contribute to the empirical literature on modeling for financial risk and portfolio management. In the portfolio optimization based on Markowitz’s mean–variance model, the Gaussian assumption can be replaced by the ARMA–GARCH model with fractional generalized hyperbolic innovations, and the portfolio value-at-risk (VaR) and average value-at-risk (AVaR) based on the model can supersede the variance risk measure.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: in the next section, Models and Methodology, the notion of long-range dependence is discussed, time-changed Brownian motion is reviewed, the generalized hyperbolic process is derived from the time-changed Brownian motion, and the fractional generalized hyperbolic process as well as the covariance structure for two elements of the processes are discussed. Section Simulation presents the simulation of fractional generalized hyperbolic processes and an illustration of the sample paths for representative parameter values. The multivariate ARMA–GARCH model with long-range dependence is defined in Section ARMA–GARCH Model with fGH Innovations, with empirical illustration. The main findings and implications are summarized in Section Conclusion.

Models and methodology

This section reviews the background knowledge regarding long-range dependence and the generalized hyperbolic process. Subsequently, a fractional generalized hyperbolic process is derived.

Long-range dependence

Long-range dependence in a stochastic process is typically defined based on its autocorrelation functions. While a short memory stationary process usually refers to a stochastic process whose autocorrelation functions decay fast and whose spectral density is bounded everywhere, a long memory processFootnote 5 is associated with the slow decay of autocorrelation functions as well as a certain type of scaling linked to self-similar processes. Although the notion of long-range dependence varies from author to author, the commonly used notion is recalled in terms of the autocorrelation function of a process. For lag k, a stationary process with autocorrelation function \(\rho (k)\) is referred to as a process with long-range dependence if

does not converge. According to this notion, absolute autocorrelations are not integrable. Thus, a weakly stationary process is said to have long-range dependence if \(\rho (\cdot )\) hyperbolically decays, that is, \(\rho (k) \sim L(k) k^{2d-1}\) as \(k \rightarrow \infty\), \(0< d < \frac{1}{2}\), where L(k) is a slowly varying function as \(x \rightarrow \infty\), if for every positive constant c,

exists and is equal to 1. Hence, the memory length in a stochastic process is measured by the rate at which its correlations decay with a lag. To illustrate, suppose an autocorrelation function \(\rho (\cdot )\) of an ARMA process at lag k. The function converges rapidly to zero as \(k \rightarrow \infty\) in the sense that there exists \(r > 1\) such that

In this case, the correlations for the ARMA processes decay exponentially fast with k. Conversely, consider the autocorrelation function \(\rho (k)\) of the FARIMA(p, d, q) process with \(0< |d| < \frac{1}{2}\). This autocorrelation function has the following property:

indicating that \(\rho (k)\) converges to zero as \(k \rightarrow \infty\) at a much slower rate than that of an ARMA process. Therefore, ARMA processes are regarded as having short memory, whereas FARIMA processes are regarded as exhibiting long memory. Likewise, the long-range dependence property depends on the behavior of the autocorrelation function at large lags. However, it may be difficult to empirically estimate the long-range dependence property (Beran 1994). Thus, self-similar processes are often used to formulate models with the long-range dependence property. A stochastic process \(\{X(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\) is said to be self-similar if there exists \(H > 0\) such that for any scaling factor \(c > 0\), the processes \(\{X(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\) and \(\{c^H X(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\) have the same law:

where H is referred to as the self-similarity exponent of the process X. For a continuous stochastic process \(x_t\), we assume that \(x_0 = 0\), \({\rm{E}}[x_t] = 0\), and the increments \(X(t) = x_t - x_{t-1}\) are stationary with \(\rm{Var}(X(t)) = \sigma ^2\). Thereafter, we have:

By the self-similarity property, the correlation is

Based on L’Hopital’s rule,

Thus, \(\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty } \sum _{k=-n}^{k-n} \rho (k)\) exist if and only if \(H < \frac{1}{2}\), and \(H > \frac{1}{2}\) implies that the series does not converge; thus, X(t) is a long-memory process.

Time-changed Brownian motion

By substituting the usual deterministic time t as subordinator \(T = \{T(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\) in a stochastic process \(Y = \{Y(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\), we obtain a new process \(X = \{X(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\), and Y is said to be subordinated by process T. Namely,

Hence, we change the time to the stochastic process Y to run on a “new clock” whose stochastic time is dominated by the subordinator T. Intuitively, it can be considered as the business time (or trading time) that can be viewed as stochastic. If we employ an arithmetic Brownian motion subordinated by a subordinator, we obtain the time-changed Brownian motion. More specifically, considering that a subordinator \(T = \{T(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\) is independent of the standard Brownian motion \(\{B(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\), we have a new process \(X = \{X(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\), which is called the time-changed Brownian motion, by substituting physical time t as the subordinator T as follows:

Let \(\mathcal{F}_T(t)\) be the filtration of T. We can derive the characteristic function \(\phi _{X(t)}\) via subordination theorem (Cont and Tankov 2004; Barndorff-Nielsen and Levendorskii 2001; Sato 1999). That is to say,

where \(\phi _{T(t)}\) is the characteristic function of the subordinator T(t). A Lévy process can be constructed by subordinating Brownian motion with a particular subordinator (Clark 1973). Therefore, subordination is used as a constructive tool to define a particular class of Lévy processes. In the next section, a generalized hyperbolic process is presented by applying time-changed Brownian motion.

Generalized hyperbolic process

The density function of the generalized inverse Gaussian distribution described by the three parameters \((\lambda , \delta , \gamma )\) is given by

where \(Y_\lambda\) is the modified Bessel function of the second kind with index \(\lambda\) as follows:

The parameter domain of the generalized inverse Gaussian distribution is

Proposition 1

The characteristic function of a generalized inverse Gaussian random variable G is given by

Proof

See Appendix. \(\square\)

Using the same approach as in the proof of Proposition 1, the rth moment can be derived as follows, given a generalized inverse Gaussian random variable G with parameters \((\lambda , \delta , \gamma )\),

where \(q(\lambda , \delta , \gamma )\) represents the norming constant of the corresponding generalized inverse Gaussian density. In this study, we set the expected value of the generalized inverse Gaussian random variable G to one, that is, \({\rm{E}}[G] = 1\). Using the moment formula in Equation (2), the expected value is defined by

and set

Then, we have a generalized inverse Gaussian random variable G under parametrization \((\lambda , \alpha )\). It follows identity

Hence, the variance of G is given by

Owing to the infinite divisibility of a generalized inverse Gaussian distribution (Barndorff-Nielson and Halgreen 1977), the characteristic function of a generalized inverse Gaussian process \(\{G(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\) with parameters \((\lambda , \alpha )\) is

where \(\nu (\lambda , \alpha ) = \Big ( \frac{\alpha ^2\ Y_{\lambda +1}(\alpha ) }{\alpha ^2\ Y_{\lambda +1} (\alpha ) - 2iu Y_\lambda (\alpha ) } \Big )^{\frac{1}{2}}\).

In the remainder of this paper, we assume that N is a positive integer that represents the dimension, and \(\beta = (\beta _1, \beta _2, \cdots , \beta _N)^\top\), \(\theta = (\theta _1, \theta _2, \cdots , \theta _N)^\top\), while \(\Sigma = [\sigma _{m, n}]_{m,n \in \{1,2, \cdots , N\}}\) is a correlation matrix such that \(\sigma _{n, n} = 1\) for \(n \in \{1,2, \cdots , N\}\). Thereafter, we consider an N-dimensional Brownian motion \(B = \{B(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\), such that \(B(t) = (B_1(t), B_2(t),\ \cdots , B_N(t) )^\top\), and suppose that \({\rm{cov}}(B_m(t), B_n(t)) = \sigma _{m, n} t\) for all \(m, n \in \{1, 2,\ \cdots , N \}\) and that B and the generalized inverse Gaussian process \(\{G(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\) with parameters \((\lambda , \alpha )\) are independent. In addition, consider the N-dimensional process \(X = \{X(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\), with \(X(t) = (X_1(t), X_2(t),\ \cdots , X_N(t) )^\top\). For \(n \in \{ 1, 2,\ \cdots , N \}\), we define \(\{X(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\) by the time-changed Brownian motion as

Thereafter, process X is referred to as the N-dimensional generalized hyperbolic process with parameters \((\lambda , \alpha , \beta , \theta , \Sigma )\). We define the characteristic function of a generalized hyperbolic process \(X_n(t)\) in the following proposition.

Proposition 2

The characteristic function of a generalized hyperbolic process \(X_n(t)\) is given by

where \(\nu _1(\lambda , \alpha , \beta _n, \theta _n) = \bigg ( \frac{\alpha ^2\ Y_{\lambda +1}(\alpha ) }{\alpha ^2\ Y_{\lambda +1} (\alpha ) - 2iu \big ( \beta _n + \frac{iu\theta _n^2}{2} \big ) Y_\lambda (\alpha ) } \bigg )^{\frac{1}{2}}\).

Proof

See Appendix. \(\square\)

Furthermore, the covariance between \(X_m(t)\) and \(X_n(t)\) is

The variance of \(X_n(t)\) is equal to

Fractional generalized hyperbolic process

The Volterra kernel \(K_H: [0, \infty ) \times [0, \infty ) \rightarrow [0, \infty ]\) is employed to define generalized hyperbolic process with long-range dependence.

with

In addition, the following facts on the Volterra kernel are provided by Houdre and Kawai (2006) and Nualart (2003):

-

1.

For \(t, s > 0\),

$$\begin{aligned} \int _{0}^{t \wedge s} K_{H} (t,\ u) K_{H} (s,\ u) du = \frac{1}{2} \big ( t^{2H} + s^{2H} - |t - s|^{2H} \big ), \end{aligned}$$(6)and

$$\begin{aligned} \int _{0}^{t} K_{H} (t, s)^2 ds = t^{2H} \end{aligned}$$(7) -

2.

If \(H \in (\frac{1}{2}, 1)\), then

$$\begin{aligned} K_H (t, s) = c_H \Big (H - \frac{1}{2} \Big ) s^{\frac{1}{2} - H} \int _{s}^{t} (u - s)^{H - \frac{3}{2}} u^{H - \frac{1}{2}} du\ \mathbbm{1}_{[0,t]}(s), \end{aligned}$$and \(K_{\frac{1}{2}}(t, s) = \mathbbm{1}_{[0,t]}(s)\).

-

3.

Let \(t > 0\) and \(p \ge 2\). \(K_{H} (t, \cdot ) \in L^p ([0,t])\) if and only if \(H \in \big ( \frac{1}{2} - \frac{1}{p} ,\ \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{p} \big )\). When \(K_{H} (t,\ \cdot ) \in L^p ([0, t])\), then

$$\begin{aligned} \int _{0}^{t} K_{H} (t, s)^p ds = C_{H, p}\ t^{p(H - \frac{1}{2}) + 1}, \end{aligned}$$where

$$\begin{aligned} C_{H, p} = c_{H}^p \int _{0}^{1} v^{p ( \frac{1}{2} - H )} \big [ (1 - v)^{H - \frac{1}{2}} - \big ( H - \frac{1}{2} \big ) \int _{v}^{1} w^{H - \frac{3}{2}} (w - v)^{H - \frac{1}{2}} dw \big ]^p dv. \end{aligned}$$

Let \(K_H (t, s)\) be the Volterra kernel and let \(X \sim GH_N (\lambda , \alpha , \beta , \theta , \Sigma )\). The N-dimensional fractional generalized hyperbolic process generated by X is defined by the process of vector \(Z = \{Z(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\) with \(Z(t) = (Z_1(t), Z_2(t),\ \cdots , Z_N(t) )^\top\), such that

for \(n \in \{ 1, 2,\ \cdots , N \}\), where

is a partition of the interval [0, t] and

We denote \(Z_n(t) = \int _{0}^{t} K_H(t, s) dX_n(s)\) and \(Z \sim fGH_N(H, \lambda , \alpha , \beta , \theta , \Sigma )\). Then, we have

where \(\nu _2(\lambda , \alpha , \beta _n, \theta _n) = \bigg ( \frac{\alpha ^2\ Y_{\lambda +1}(\alpha ) }{\alpha ^2\ Y_{\lambda +1} (\alpha ) - 2iu K_H(t,s) \big ( \beta _n + \frac{iu\theta _n^2}{2} \big ) Y_\lambda (\alpha ) } \bigg )^{\frac{1}{2}}\). Therefore, the characteristic function of \(Z_n(t)\) is given by

Proposition 3

For \(n \in \{1, 2,\ \cdots , N \}\), the covariance between \(Z_n(s)\) and \(Z_n(t)\) is equal to

Proof

See Appendix. \(\square\)

Proposition 4

For \(m, n \in \{ 1, 2,\ \cdots , N \}\), the covariance between \(Z_m(t)\) and \(Z_n(t)\) is equal to

Proof

See Appendix. \(\square\)

For a given stochastic process \(Y = \{Y(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\), the summation

diverges. From Proposition 3 and Equation (1),

where \(\eta = \beta _n^2 \Big ( \frac{Y_\lambda (\alpha )\ Y_{\lambda +2}(\alpha ) }{Y_{\lambda +1}^2 (\alpha )} - 1 \Big ) + \theta _n^2\). This becomes \(\eta H(2H-1)j^{2H-2}\) as \(j \rightarrow \infty\). Hence, \(\sum _{j=1}^{\infty } {\rm{E}}\big [ Z_n(1) \big ( Z_n(j+1) - Z_n(j) \big ) \big ]\) diverges, that is, the process \(\{Z(t)\}_{t \ge 0}\) has long-range dependence when \(\frac{1}{2}< H < 1\).

Simulation

In this section, the sample paths of fractional generalized hyperbolic processes are simulated by subordinating a discretized generalized inverse Gaussian process with fractional Brownian motion at equally spaced intervals. First, the generalized inverse Gaussian process G(t) is simulated as followsFootnote 6:

-

1.

Choose M fixed times in [0, t]: \(t_0 = 0, t_1 = t / M,\ \cdots , t_{M-1} = (M - 1)t / M,\) and \(t_M = t\).

-

2.

Generate M generalized inverse Gaussian variates \((G(t_1), G(t_2),\ \cdots , G(t_M))\).

Let \(L_\Sigma\) be the lower triangular matrix obtained by the Cholesky decomposition for \(\Sigma\) with \(\Sigma = L_\Sigma L_\Sigma ^T\), where \(\Sigma\) is the correlation matrix in Equation (3). Thus, we obtain a mutually independent vector of Brownian motion \({\bar{B}}(t) = ({\bar{B}}_1(t), {\bar{B}}_2(t),\ \cdots , {\bar{B}}_N(t) )^\top\).

The sample paths of \(X \sim GH_N(\lambda , \alpha , \beta , \theta , \Sigma )\) are generated as follows: for a given partition in 1) above,

where \(\epsilon _{j, n} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 1)\). Therefore, we have

where \(\epsilon _j = (\epsilon _{j,1}, \epsilon _{j,2},\ \cdots , \epsilon _{j,N} )^T\), \(\epsilon _{j, n} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 1)\), and \(\epsilon _{j, m}\) is independent of \(\epsilon _{j, n}\) for all \(m, n \in \{1, 2,\ \cdots , N \}\) and \(j \in \{1, 2,\ \cdots , M \}\).

Finally, the sample paths of \(Z \sim fGH_N(H, \lambda , \alpha , \beta , \theta , \Sigma )\) are generated as follows:

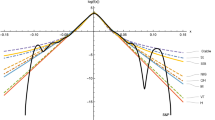

Figure 1 presents sample paths of the generalized inverse Gaussian subordinator G(t) with parameters \(\lambda = -1.2\), \(\delta = 0.1\), and \(\gamma = 0.01\) for \(t_M = 1\) and \(\Delta t = 1/250\) as well as \(\lambda = -0.5\), \(\delta = 0.2\), and \(\gamma = 0.03\) for \(t_M = 5\) and \(\Delta t = 1/250\). Figure 2 shows sample paths of the univariate fractional generalized hyperbolic process Z(t) with parameters \(\lambda = -1.2\), \(\delta = 0.1\), \(\gamma = 0.01\), \(\beta = -0.05\), \(\theta = 0.1\), and \(H = 0.65\) for \(t_M = 1\) and \(\Delta t = 1/250\) as well as \(\lambda = -0.5\), \(\delta = 0.2\), \(\gamma = 0.03\), \(\beta = -0.01\), \(\theta = 0.08\), and \(H = 0.70\) for \(t_M = 5\) and \(\Delta t = 1/250\). Figure 3 illustrates pairs of sample paths of the two dimensional fractional generalized hyperbolic process \(Z = (Z_1(t), Z_2(t))\) for \(t \ge 0\) with the different parameters and series lengths.

ARMA–GARCH model with fGH innovations

Let \(Z \sim fGH_N (H, \lambda , \alpha , \beta , \theta , \Sigma )\) be generated by \(X \sim GH_N (\lambda , \alpha , \beta , \theta , \Sigma )\). An N-dimensional discrete time process \(y = \{y(t_k)\}_{k \in \{0,1,2, \cdots \}}\) with \(y(t_k) = (y_1(t_k), y_2(t_k), \cdots , y_N(t_k))\) is referred to as the N-dimensional ARMA–GARCH model with fGH innovations when it is given by the ARMA(1,1)-GARCH(1,1) model as follows: \(y_n(t_0) = 0\) and \(\varepsilon _n(t_0) = 0\), and

where \(\varepsilon _n(t_{k+1}) = Z_n(t_{k+1})- Z_n(t_{k})\) and \(n \in \{1, 2, \cdots , N\}\). This model describes the volatility clustering effect of the GARCH(1, 1) model, as well as the fat-tail and the asymmetric dependence between elements by the generalized hyperbolic process X, and the long-range dependence by the fractional generalized hyperbolic process Z. Because \(Z_n(t_k)\) can be approximated as

its increment \(Z_n(t_{k+1}) - Z_n(t_k)\) is expressed as follows:

Let N be the number of assets in the portfolio and M be the number of time steps. The parameters of the models are estimated using the following steps:

-

1.

Estimate ARMA(1,1)-GARCH(1,1) parameters \(\mu _n\), \(a_n\), \(b_n\), \(\omega _n\), \(\xi _n\), and \(\zeta _n\) with standard normal innovations by maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) with assumption \(\sigma _n^2(t_0) = \frac{\kappa _n}{(1 - \xi _n - \zeta _n)}\) for \(n = 1, 2, \cdots , N\).

-

2.

Using the estimated parameters, extract residuals \(\varepsilon _n (t_k)\) for \(n = 1, 2, \cdots , N\) and \(k = 1, 2, \cdots , M\).

-

3.

Estimate the Hurst index \(H_n\) of \(\{\varepsilon _n(t_k)\}_{k = 1, 2, \cdots , M}\) using rescaled range (R/S) analysis (Hurst 1951; Lo 1991; Qian and Rasheed 2004). Then, parameter H is obtained as the mean of \(H_n\) for \(n = 1, 2, \cdots , N\).

-

4.

Let \(Z_n(t_k) = \sum _{j=1}^{k} \varepsilon _n(t_j)\), and extract \(\{X_n(t_k)\}_{k = 1, 2, \cdots , M}\) for \(n = 1, 2, \cdots , N\) as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} X_n(t_1)&= \frac{Z_n(t_1)}{K_H (t_1, t_0)} \quad \text {and} \nonumber \\ X_n(t_k)&= X_n(t_{k-1}) + \frac{Z_n(t_k) - Z_n(t_{k-1})}{K_H (t_k, t_{k-1})} \nonumber \\&\quad - \sum _{j=0}^{k-2} \frac{K_H(t_k, t_j) - K_H(t_{k-1}, t_j)}{K_H(t_k, t_{k-1})}\ \big ( X_n(t_{j+1}) - X_n(t_j) \big ) \nonumber \\&\qquad \text {for}\ k = 2, 3, \cdots , M. \end{aligned}$$(8) -

5.

Estimate the parameters \(\Theta _n = (\lambda _n, \alpha _n, \beta _n, \theta _n)\) of the generalized hyperbolic process using \(\{X_n(t_k)\}_{k = 1, 2, \cdots , M}\) extracted in the step 4) for \(n = 1, 2, \cdots , N\) as follows: the likelihood function for the observations \(\{X_n(t_k)\}_{k = 1, 2, \cdots , M}\) is given by

$$\begin{aligned} & f(X_{n} (t_{1} ), \ldots ,X_{n} (t_{M} );\Theta _{n} ) = f(X_{n} (t_{M} )|X_{n} (t_{1} ), \ldots ,X_{n} (t_{{M - 1}} );\Theta _{n} ) \\ & \quad \cdot f(X_{n} (t_{{M - 1}} )|X_{n} (t_{1} ), \ldots ,X_{n} (t_{{M - 2}} );\Theta _{n} ) \cdots f(X_{n} (t_{1} );\Theta _{n} ). \\ \end{aligned}$$The maximum likelihood estimator of the parameters \(\Theta _n\) for the generalized hyperbolic innovations is defined by maximizing the log-likelihood function given above.

$$\begin{aligned} {\hat{\Theta }}_n = \arg \max _{\Theta _n} \sum _{k=1}^{M} \log \big (f(X_n(t_k)) | X_n(t_1), \cdots , X_n(t_{k-1}); \Theta _n\big ). \end{aligned}$$ -

6.

Setting \(\lambda = \sum _{n=1}^{N} \frac{\lambda _n}{N}\) and \(\alpha = \sum _{n=1}^{N} \frac{\alpha _n}{N}\), estimate the parameters \(\beta _n\) and \(\theta _n\) again using \(\{X_n(t_k)\}_{k = 1, 2, \cdots , M}\) by means of MLE for \(n = 1, 2, \cdots , N\) as in step 5).

-

7.

From the data \(\{ (X_m(t_k),\ X_n(t_k) \}_{k = 1, 2, \cdots , M}\) extracted in the Step 4), calculate the covariance between \(X_m(t_1)\) and \(X_n(t_1)\) for \(m, n \in \{ 1, 2, \cdots , N \}\). We estimate \(\Sigma = [\sigma _{m, n}]_{m, n \in \{1, 2, \cdots , N\}}\) using Equation (4) and \({\rm{cov}}(X_m(t_1),\ X_n(t_1))\).

To estimate the parameters and covariance matrix discussed above, 2, 730 observed 1-minute stock prices of IBM Co., Johnson & Johnson, Oracle Co., Apple Inc., Amazon.com, Inc., and CVS Health Co. for 7 trading days from February 5 to February 13, 2020, are obtainedFootnote 7. The estimated ARMA(1,1)-GARCH(1,1) parameters \(\mu _n\), \(a_n\), \(b_n\), \(\omega _n\), \(\xi _n\), and \(\zeta _n\) with standard normal innovations are presented in Table 1. The residuals, which are obtained from the estimated parameters, are used to compute the Hurst index \(H_n\) for \(n = 1,2, \cdots , N\), and they are reported in Table 2, with the estimated \(H = 0.5387\) as the mean of \(H_n\). The estimated fractional generalized hyperbolic parameters H, \(\lambda\), \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), and \(\theta\) are listed in Table 3 along with the estimated non-fractional generalized hyperbolic parameters. Note that the ARMA–GARCH model with fractional generalized hyperbolic innovations becomes the ARMA–GARCH model with non-fractional generalized hyperbolic innovations when parameter \(H = 1/2\). The estimated matrix \(\Sigma\) is given in Table 4.

Three criteria are used to compare the goodness-of-fit of the innovation processes under consideration: the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test statistics, log-likelihood (LL), and Akaike information criterion (AIC). The KS test is performed based on the statistic:

where \({\hat{F}}(x)\) and F(x) are the empirical sample and estimated theoretical distributions, respectively. The KS statistics are calculated for the fractional generalized hyperbolic distribution with estimated parameters \((\lambda ,\ \alpha ,\ \beta _n,\ \theta _n)\) and the empirical sample distribution of \(\{X_n(t_k) - X_n(t_{k-1})\}\) for \(k = 1,2, \cdots , M\), where \(X_n(t_k)\) is the extracted process using Equation (8). The p-values of the KS statisticFootnote 8 represent the amount of evidence available to invalidate the null hypothesis that the data are drawn from the concerned theoretical distribution. Hence, the smaller the p-values, the more the evidence against the null hypothesis. The LL is an overall measure of the goodness-of-fit, implying that higher values are more likely to be the distribution candidates for modeling the data. The AIC is a measure of the goodness-of-fit that estimates the relative support for a model, which is

where w is the number of parameters in the calibrated model and L is the maximized value of the likelihood function of the estimated model.

Table 5 presents the goodness-of-fit tests of the innovation processes of each model. The ARMA–GARCH model with fractional generalized hyperbolic innovations is not rejected by KS statistics at the 10% significance level for all the six stock returns, which means the empirical sample distribution is not statistically different from the estimated theoretical distribution. However, the ARMA–GARCH models with non-fractional and normal innovations are rejected at the 10% significance level for all considered stocks. Indeed, the fractional generalized hyperbolic models have the highest LL as well as the smallest AIC for all the innovation processes analyzed. Furthermore, to assess the power of the goodness-of-fit tests for a small sample size, 390 observed 1-minute stock prices of the six companies are taken, and these are the prices on February 5, and the same estimation/test procedures are followed. The inferences from Table 5 are consistent as shown in Table 6. Consequently, these results suggest that the ARMA–GARCH model with fractional generalized hyperbolic innovations can be used as an approximation to the empirical sample distribution. Figure 4 exhibits the distributions of the residuals from the models for each stock. Therefore, it is noteworthy that the ARMA–GARCH model with fractional generalized hyperbolic innovations better describes the behavior of the high-frequency stock returns considered in this study than the ARMA–GARCH models with non-fractional generalized hyperbolic and normal innovations. In this regard, portfolio VaR and AVaR based on the ARMA–GARCH models with fractional generalized hyperbolic innovations can be applied to the portfolio optimization. As alternative risk measures, the VaR and AVaR can overcome the limitations of the use of portfolio variance as a measure of risk. In portfolio optimization that portfolio managers and investors use for portfolio rebalancing, a crucial measure is the marginal risk contribution to the portfolio (Gourieroux et al. 2000), which is the risk measure with respect to a given portfolio holding. Hence, by employing the VaR and AVaR calculated by the ARMA–GARCH model with fractional generalized hyperbolic innovations, we can find the optimal portfolio. Moreover, we obtain encouraging results from the goodness-of-fit test that it can be applied to an option pricing model equipped with volatility clustering, leverage effect and conditional skewness, leptokurtosis, and long-range dependence.

Conclusion

In this study, the non-fractional generalized hyperbolic process is derived by subordinating the time-changed Brownian motion to the generalized inverse Gaussian process, and the fractional generalized hyperbolic process is obtained using the Volterra kernel. Thereafter, we introduce the multivariate ARMA–GARCH model with fractional generalized hyperbolic innovations that exhibit three-stylized facts: fat tail, volatility clustering, and long-range dependence properties. This model is compared with ARMA–GARCH models with non-fractional generalized hyperbolic and normal innovations. The fractional generalized hyperbolic process performs better in describing the behavior of the residual process of high-frequency returns than the non-fractional generalized hyperbolic process or Gaussian process. Although the results reveal some important insights into high-frequency return data, the models considered here disregard the structural changes in their dependence structure. This limitation can be addressed in future studies by utilizing regime-switching methods (Hamilton 1989, 1990; Hackbarth et al. 2006) or clustering algorithms (Kou et al. 2014; Li et al. 2021; Wen et al. 2014).

Availability of data and materials

All data in the paper come from publicly available sources and can be provided upon request.

Notes

One can find a large number of specifications of ARCH and GARCH models in the literature which have been considered for financial market data. Readers are referred to the surveys on those models by Bera and Higgins (1993), Bollerslev et al. (1992), Bollerslev et al. (1994), Gourieroux (1997), and Li et al. (2002).

Refer to Samorodnitsky and Taqqu (1994) for stable process.

The fractional tempered stable process is also discussed on the option pricing by Kim et al. (2019).

Long memory and long-range dependence are synonymous notions.

R version 4.1.1 is used for numerical analyses throughout this article.

Given that the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) has normal trading hours from 9:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., one day is set to 390 minutes, meaning \(\Delta t = 1/390\).

Abbreviations

- ARMA:

-

Autoregressive moving average

- ARCH:

-

Autoregressive conditional heteroskedastic

- GARCH:

-

Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedastic

- GED:

-

Generalized error distribution

- GH:

-

Generalized hyperbolic

- GIG:

-

Generalized inverse Gaussian

- B(t):

-

Brownian motion at time t

- VaR:

-

Value-at-risk

- AVaR:

-

Average value-at-risk

- FARIMA:

-

Fractionally differenced autoregressive integrated moving average

- \(\rho (\cdot )\) :

-

Autocorrelation function

- H :

-

Self-similarity exponent of a process or Hurst index

- \(\mathcal{F}\) :

-

Filtration

- \(\phi\) :

-

Characteristic function

- \(Y_\lambda\) :

-

Modified Bessel function of the second kind with index \(\lambda\)

- \(\sigma _{m, n}\) :

-

Correlation matrix whose (m, n) entry is the correlation

- fGH:

-

Fractional generalized hyperbolic

- \(K_H\) :

-

Volterra kernel with Hurst index H

- \(\approx\) :

-

Approximately equal to

- \(\mathcal{N}\) :

-

Normal distribution

- MLE:

-

Maximum likelihood estimation

- R/S:

-

Rescaled range

- KS:

-

Kolmogorov–Smirnov

- LL:

-

Log-likelihood

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

- \(\overset{d}{=}\) :

-

Equal in distribution

- \(\wedge\) :

-

Minimum

- \(\vee\) :

-

Maximum

References

Aas K, Haff IH (2006) The generalized hyperbolic skew student’s t-distribution. J Financ Econ 4(2):275–309

Anderson J (2001) On the normal inverse gaussian stochastic volatility model. J Bus Econ Stat 19:44–54

Baillie RT, Bollerslev T (2002) The message in daily exchange rates: a conditional variance tale. J Bus Econ Stat 20(1):60–68

Barndorff-Nielsen OE (1977) Exponentially decreasing distributions for the logarithm of particle size. Proc Roy Soc 353:401–419

Barndorff-Nielsen OE (1995) Normal inverse Gaussian processes and the modelling of stock returns. Research report 300. Department of Theoretical Statistics, Institute of Mathematics, University of Aarhus

Barndorff-Nielsen OE, Levendorskii SZ (2001) Feller processes of normal inverse Gaussian type. Quant Finance 1(3):318–331

Barndorff-Nielson OE, Halgreen CZ (1977) Infinite divisibility of the hyperbolic and generalized inverse gaussian distributions. Probab Theory Relat Fields 38(4):309–311

Beck A, Kim YS, Rachev ST, Feindt M, Fabozzi F (2013) Empirical analysis of Arma–Garch models in market risk estimation on high-frequency U.S. data. Stud Nonlinear Dyn Econ 17:167–177

Bera AK, Higgins ML (1993) ARCH models: properties, estimation and testing. J Econ Surv 7:305–366

Beran J (1994) Statistics for long-memory processes, vol 61. Monographs on statistics and applied probability. Champman and Hall, New York

Biagini F, Hu Y, Øksendal B, Zhang T (2008) Stochastic calculus for fractional Brownian motion and applications. Springer, New York

Bollerslev T (1986) Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. J Econ 31:307–327

Bollerslev T (1987) A conditional heteroskedastic time series model for security prices and rates of return data. Rev Econ Stat 69:542–547

Bollerslev T, Chou R, Kroner KF (1992) ARCH modeling in finance: a review of the theory and empirical evidence. J Econ 52:5–59

Bollerslev T, Engle RF, Nelson D (1994) ARCH models. Handb Econ 4:2959–3038

Casas I, Gao J (2008) Econometric estimation in long-range dependent volatility models: theory and practice. J Econ 147(1):72–83

Cheridito P (2003) Arbitrage in fractional Brownian motion models. Finance Stochast 7(4):533–553

Choi P, Nam K (2008) Asymmetric and leptokurtic distribution for heteroscedastic asset returns: the SU-normal distribution. J Empir Financ 15(1):41–63

Chronopoulou A, Viens FG (2012) Stochastic volatility and option pricing with long-memory in discrete and continuous time. Quant Finance 12(4):635–649

Clark P (1973) A subordinated stochastic process model with finite variation for speculative prices. Econometrica 41(1):135–155

Comte F, Renault E (1998) Long memory in continuous-time stochastic volatility models. Math Financ 8(4):291–323

Cont R (2005) Long range dependence in financial markets. Fractals in engineering. Springer, London, pp 159–179

Cont R, Tankov P (2004) Financial modelling with jump processes. Chapman and Hall/CRC, London

Coutin L (2007) An introduction to Stochastic calculus with respect to fractional Brownian motion. Springer, New York

Cutland NG, Kopp PE, Willinger PE (1995) Stock price returns and the Josef effect: a fractional version of the black-scholes model. In: Bolthausen E, Dozzi M, Russo F (eds) Seminar on Stochastic analysis. Random fields and applications. Progress in probability, vol 36. Birkhäuser, Basel, pp 327–351

Doukhan P, Oppenheim G, Taqqu M (2002) Theory and applications of long-range dependence. Springer, New York

Eberlein E, Hammerstein EA (2004) Generalized hyperbolic and inverse Gaussian distributions: limiting cases and approximation of processes. Seminar on stochastic analysis, random fields and applications IV. Birkhäuser, Basel

Engle R (1982) Autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity with estimates of the variance of united kingdom inflation. Econometrica 50:987–1007

Fama EF (1970) Efficient capital markets: a review of theory and empirical work. J Finance 25:383–417

Forsberg L, Bollerslev T (2002) Bridging the gap between the distribution of realized (ECU) volatility and ARCH modeling (of the EURO): the GARCH-NIG model. J Appl Economet 17:535–548

Gourieroux C (1997) ARCH models and financial applications. Springer, New York

Gourieroux C, Laurent J, Scaillet O (2000) Sensitivity analysis of values at risk. J Empir Financ 7:225–245

Granger C, Ding Z (1995) Some properties of absolute return, an alternative measure of risk. Annales d’Economie et de Statistique 40:67–91

Hackbarth D, Miao J, Morellec E (2006) Capital structure, credit risk, and macroeconomic conditions. J Financ Econ 82:519–550

Hamilton JD (1989) A new approach to the economic analysis of nonstationary time series and the business cycle. Econometrica 57(2):357–384

Hamilton JD (1990) Analysis of time series subject to changes in regime. J Econ 45:39–70

Harvey CR, Siddique A (1999) Autoregressive conditional skewenss. J Financ Quant Anal 34(4):465–487

Houdre C, Kawai R (2006) On fractional tempered stable motion. Stochastic Process Appl 116(2):1161–1184

Hurst HE (1951) Long term storage capacity of reservoirs. Trans Am Soc Civ Eng 116:770–799

Jensen M, Lunde A (2001) The NIG-S & ARCH model: a fat-tailed stochastic, and autoregressive conditional heteroscedastic volatility model. Econ J 4:319–342

Johnson NL (1949) Systems of frequency curves generated by methods of translation. Biometrika 36(1/2):149–176

Kaarakka T, Salminen P (2011) On fractional Ornstein–Uhlenbeck processes. Commun Stochastic Anal 5(1):121–133

Kim YS (2012) The fractional multivariate normal tempered stable process. Appl Math Lett 25:2396–2401

Kim YS (2015) Multivariate tempered stable model with long-range dependence and time-varying volatility. Front Appl Math Stat 1:1–12

Kim YS, Rachev ST, Bianchi ML, Fabozzi FJ (2009) A new tempered stable distribution and its application to finance. In: Risk Assessment. Physica-Verlag HD, pp 677–707

Kim YS, Jiang D, Stoyanov S (2019) Long and short memory in the risk-neutral pricing process. J Deriv 26(4):71–88

Kou G, Peng Y, Wang G (2014) Evaluation of clustering algorithms for financial risk analysis using MCDM methods. Inform Sci 275:1–12

Kozubowski TJ, Meerschaert MM, Podgorski K (2006) Fractional Laplace motion. Adv Appl Probab 38(2):451–464

Kumar A, Vellaisamy P (2012) Fractional normal inverse Gaussian process. Methodol Comput Appl Probab 14(2):263–283

Kumar A, Meerschaert MM, Vellaisamy P (2011) Fractional normal inverse Gaussian diffusion. Statist Probab Lett 81:146–152

Li T, Kou G, Peng Y, Philip SY (2021) An integrated cluster detection, optimization, and interpretation approach for financial data. IEEE Trans Cybern

Li WK, Ling S, McAleer M (2002) Recent theoretical results for time series models with GARCH errors. J Econ Surv 16(3):245–269

Liu S, Brorsen BW (1995) Maximum likelihood estimation of a Garch stable model. J Appl Econ 10:273–285

Lo AW (1991) Long-term memory in stock market prices. Econometrica 59:1279–1313

Madan DB, Seneta E (1990) The variance gamma (v.g.) model for share market returns. J Bus 63(4):511–524

Mandelbrot BB (1963) New methods in statistical economics. J Polit Econ 71:421–440

Mandelbrot BB (1963) The variation of certain speculative prices. J Bus 36:394–419

Mandelbrot BB, Van Ness JW (1968) Fractional Brownian motions, fractional noises, and applications. SIAM Rev 10:422–437

Mariani MC, Florescu I, Varela MB, Ncheuguim E (2009) Long correlations and lévy modes applied to the study of memory effects in high frequency (tick) data. Physica A 388(8):1659–1664

Markowitz H (1952) Portfolio selection. J Finance 7(1):77–91

Marsaglia G, Marsaglia J (2004) Evaluating the Anderson–Darling distribution. J Stat Softw 9(2):1–5

Marsaglia G, Tsang W, Wang G (2003) Evaluating Kormogorov’s distribution. J Stat Softw 8(18):1–4

McNeil AJ, Frey R, Embrechts P (2005) Quantitative risk management, concepts, techniques and tools. Princeton series in Finance. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Mercado LCCB (2011) Portfolio optimization under generalized hyperbolic distribution of returns and exponential utility. PhD Thesis, Northwestern University

Mittnik S, Paolella MS (2003) Prediction of financial downside-risk with heavy-tailed conditional distributions. Handbook of heavy tailed distributions in finance, North-Holland, pp 385–404

Mittnik S, Paolella MS, Rachev ST (1998) Unconditional and conditional distributional models for the Nikkei index. Asia-Pacific Finan Markets 5:99–1281

Naguez N (2018) Dynamic portfolio insurance strategies: risk management under Johnson distributions. Ann Oper Res 262(2):605–629

Naguez N, Prigent JL (2017) Optimal portfolio positioning within generalized Johnson distributions. Quat Finance 17(7):1037–1055

Nelson DB (1991) Conditional heteroskedasticity in asset returns: a new approach. Econometrica 59(2):347–370

Nualart D (2003) Stochastic integration with respect to fractional Brownian motion and applications. Contemp Math 336:3–39

Panorska A, Mittnik S, Rachev ST (1995) Stable arch models for financial time series. Appl Math Lett 8:33–37

Prause K (1999) The generalized hyperbolic model: estimation, financial derivatives, and risk measures. PhD Thesis, University of Freiburg

Qian B, Rasheed K (2004) Hurst exponent and financial market predictability. In: Proceedings of the second IASTED international conference on financial engineering and applications

Rigby RA, Stasinopoulos DM (2005) Generalized additive models for location, scale, and shape. J Roy Stat Soc Ser C (Appl Stat) 54(3):507–554

Robinson P (2003) Time series with long memory. Advanced texts in econometrics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Rosenbaum M (2008) Estimation of the volatility persistence in a discretely observed diffusion model. Stochastic Process Appl 118(8):1434–1462

Rosiński J (2007) Tempering stable processes. Stochastic Process Appl 117(6):677–707

Samorodnitsky G, Taqqu MS (1994) Stable non-Gaussian random processes. Chapman & Hall, CRC, Boca Raton

Sato K (1999) Lévy processes and infinitely divisible distributions. Cambridge University Process, Cambridge

Stentoft L (2008) American option pricing using GARCH models and the noraml inverse Gaussian distribution. J Financ Econ 6:540–582

Sun W, Rachev ST, Fabozzi F (2008) Long-range dependence, fractal processes, and intra-daily data. In: Seese D, Weinhardt C, Schlottmann F (eds) Handbook on information technology in finance. International handbooks information system. Springer, Berlin

Venter J, De Jongh P (2002) Risk estimation using the normal inverse Gaussian distribution. J Risk 4:1–24

Wen F, Xu L, Ouyang G, Kou G (2014) Retail investor attention and stock price crash risk: evidence from China. Int Rev Financ Anal 65:101376

Willinger W, Taqqu MS, Teverovsky V (1999) Stock market prices and long-range dependence. Finance Stochastic 3(1):1–13

Yan J (2005) Asymmetry, fat-tail, and autoregressive conditional density in financial return data with systems of frequency curves. Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science, University of Iowa, Iowa

Acknowledgements

I thank the Managing Editor-in-Chief Dr. Gang Kou and the eight anonymous referees for their insightful comments that greatly improved this article.

Funding

No outside funding was received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author carried out all of the research, including the compilation and analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. The author has read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares that there are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Proof of Proposition 1

Let \(q(\lambda , \delta , \gamma ) = \big ( \frac{\gamma }{\delta } \big )^\lambda \frac{1}{2Y_\lambda (\delta \gamma )}\) denote the norming constant of the generalized inverse Gaussian density, then the characteristic function of G is

\(\square\)

One can also find the characteristic function of the generalized inverse Gaussian distribution in McNeil et al. (2005) with different parameterization.

Proof of Proposition 2

Since for all \(t \ge 0\) we have \(\log \phi _{G(t)} (u) = t \log \phi _{G(1)} (u)\), the characteristic function of \(X_n(t)\) is

where \(\nu _1(\lambda , \alpha , \beta _n, \theta _n) = \bigg ( \frac{\alpha ^2\ Y_{\lambda +1}(\alpha ) }{\alpha ^2\ Y_{\lambda +1} (\alpha ) - 2iu \big ( \beta _n + \frac{iu\theta _n^2}{2} \big ) Y_\lambda (\alpha ) } \bigg )^{\frac{1}{2}}\). \(\square\)

Proof of Proposition 3

Then, we have

By the property of the generalized hyperbolic process \(X_n\), we have

Hence, we obtain

\(\square\) Refer to Prause (1999), Mercado (2011), and Eberlein and Hammerstein (2004) in more details on the properties of the generalized hyperbolic process.

Proof of Proposition 4

Let P be a partition such that

We have

By the property of the generalized hyperbolic process, we have

Hence, we obtain

\(\square\)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S.I. ARMA–GARCH model with fractional generalized hyperbolic innovations. Financ Innov 8, 48 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-022-00349-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-022-00349-2