Abstract

Background

Intestinal knot formation is a condition wherein two segments of the intestine are knotted together; however, reports of small-intestinal ileo-ileal knot formation are rare.

Case presentation

The patient was a 62-year-old Asian male with a history of endoscopic colorectal adenoma resection and a spontaneous pneumothorax. The patient had no history of a laparotomy. He consulted his local doctor with the chief complaint of abdominal pain and was admitted to our hospital with suspicion of an acute abdomen. The abdomen had muscular guarding with tenderness and rebound tenderness. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed torsion of the mesentery of the small intestine with poor contrast filling. The patient was referred to our department with strangulated bowel obstruction and underwent an emergency laparotomy. Intraoperative findings revealed that two segments of the ileum were wrapped around each other to form a knot, and the strangulated small bowel was necrotic. After the release of the knot, partial resection of the small intestine was performed from 220 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz to 80 cm proximal to the cecum. The patient had a good postoperative course and was discharged on the 11th postoperative day.

Conclusion

Ileo-ileal knots should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis when treating strangulated bowel obstruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Intestinal knots can cause intestinal obstruction when two intestinal segments wrap around each other to form a knot, resulting in severe ischemia and obstruction. Most case reports have discussed knots that formed between the ileum and sigmoid colon. However, reports of ileo-ileal knots (IIK) are rare [1, 2]. Moreover, the etiology and risks for the development of IIKs remain unclear. In this report, we describe a case of a patient with an IIK that had a favorable outcome following early surgery. Moreover, a literature review on IIKs is described.

Case presentation

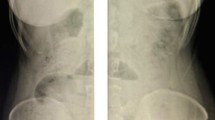

The patient was a 62-year-old male with a history of endoscopic resection of colorectal adenoma and spontaneous pneumothorax. The patient had no history of a laparotomy. He consulted his local doctor with the chief complaint of abdominal pain and was admitted to our hospital with an acute abdomen. The abdomen had muscular guarding with tenderness and rebound tenderness. His vital signs were normal, including a pulse rate of 73 bpm, blood pressure of 125/73 mmHg, temperature of 37.2 °C, and oxygen saturation of 100% on room air. Blood tests revealed a normal white blood cell count and C-reactive protein level. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed torsion of the mesentery of the small intestine with poor contrast enhancement (Fig. 1a, b). The coronal section showed an 8-shaped small intestine with reduced contrast enhancement and surrounding ascites (Fig. 1b).

a The mesentery of the small intestine is shown twisted (red arrow), with reduced contrast enhancement of the intestinal wall. b The small intestine is shown twisted and constricted (red arrow), resulting in decreased contrast enhancement of the intestinal wall in a figure-8 pattern centered at the site (oval)

The patient was referred to our department with a diagnosis of strangulated bowel obstruction, and an emergency laparotomy was performed within 6 h of symptom onset. Intraoperative findings showed that the ileal loops were wrapped around each other to form a knot, and the strangulated intestine was necrotic (Fig. 2a, b). When the knot was released, two segments of the ileum were visibly necrotic (Fig. 3). Partial resection of the small intestine was performed from 220 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz to 80 cm proximal to the cecum.

Macroscopic specimen findings showed that the resected intestinal tract was approximately 150 cm long, and most of the mucosal surface was black. The histopathological examination revealed congestion and ischemic necrosis.

The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on the 11th postoperative day.

Discussion

Intestinal knots are obstructions formed by two mobile intestinal loops that wrap around each other, either mutually or by one strangulating the other, and are associated with severe impairment of the perfusion of the intestinal tract. This condition was first mentioned by Riverius in the sixteenth century and reported in more detail by Rokitansky in 1836.

Taylor [3] classified true knots as those in which one of the two intestinal loops passes through the crossing aperture and then wraps around the other, and intertwined (pseudo) knots as those in which the other does not pass through the crossing aperture. True knots generally form between the small intestine and sigmoid colon; however, knots forming between small intestinal loops are rare [3,4,5]. In the present case, a true knot was formed between two small intestinal loops.

Although the etiology of IIKs is unknown, anatomic factors such as decreased mesenteric fat, elongated mesenteries, and narrow bases [6] and dietary factors such as fasting habits, high fiber, and a single bulky meal have been implicated in the development of ileo-sigmoid knots [5]. It is speculated that the anatomical risk factors increase the mobility of the intestinal tract, and the dietary factors cause a large amount of content to flow into the small intestine in a short period of time, resulting in increased intestinal peristalsis and leading to knot formation [7, 8].

In the present case, although the patient had a normal body mass index (BMI) of 19 kg/m2, intraoperative findings revealed an oversized mesentery and low mesenteric fat content, and patient history revealed a habit of consuming large amounts of food in a short period of time. Thus, both anatomic and dietary risk factors were present in this case.

A search of PubMed and Google Scholar databases revealed 13 cases of IIKs with true knot formation that have been reported from 2010 to 2022 [4, 6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], including this case (Table 1). Most reported cases were from India (six cases) [8, 9, 11,12,13,14], followed by Japan (three cases, including this case) [4, 7]. The remaining four were from Greece [6], Ethiopia [10, 16], and Malaysia [15].

Of the 13 previously reported cases, 3 were described as having adhesions related to intestinal knots [7, 11, 15]. Others stated that increased mobility of the intestinal tract promoted knot formation [4, 8, 14]. Since the majority of cases of knot formation occurred within 30 cm proximal of the ileocecal area, it was hypothesized that "moderate adhesions and exaggerated intestinal peristalsis" promote knot formation [7]. However, in the present case, the knot was formed 80 cm proximal to the cecum, and there were no adhesions. It is important to note that some IIKs may develop without any associated adhesions. We believe that the most important factor for IIK formation is increased intestinal motility and that adhesions may or may not be relevant.

Preoperative diagnosis of IIKs is very difficult, and in all reported cases, the diagnosis was made intraoperatively. In our patient, the preoperative diagnosis was strangulated bowel obstruction, and the diagnosis of IIK was also only made intraoperatively. Preoperatively, we had no knowledge of IIK and were unable to make the diagnosis. However, retrospectively, the CT scan showed that the small intestine formed a double-closed loop. In countries with limited medical resources, CT scans are not frequently conducted, resulting in few confirmed cases; however, as noted by Kanamori et al., the presence of a double-closed loop may be a specific finding of IIKs [7].

Although most cases were operated within 6 to 48 h after symptom onset, 11 of 13 cases required intestinal resections. The need for intestinal resection in IIK does not seem to correlate with the onset time. As noted in two cases [12, 14], only obstruction release was required even though two days had passed since the onset of symptoms. Therefore, it is speculated that the need for intestinal resection depends not on the time of symptom onset but on the degree of strangulation associated with knot formation. Therefore, if strangulation due to the knot formation is severe, even a short time after onset, intestinal resection becomes inevitable. Given that it is currently impossible to evaluate the level of strangulation using available medical technology, early treatment is crucial.

There is no clear consensus on the appropriate surgical method for IIKs regarding the release of the knot before resection. Some studies recommend en bloc resection without relieving the obstruction because of the risk of necrotic material entering the systemic circulation and intestinal perforation [9, 10, 12, 17]. Conversely, another set of studies suggested releasing the obstruction first to avoid excessive intestinal resection [14, 18]. In two reports, surgery was carried out without intestinal resection, and benefits were noted by releasing the knot first [12, 14]. In this case, the small bowel knot was released to minimize the length of resected. The patient's general health should be considered, and surgery should be performed accordingly to minimize resection of the intestinal tract, with or without knot release.

Conclusions

Here, we report a case of strangulated bowel obstruction caused by an IIK. This should be considered when treating strangulated bowel obstruction.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- IKK:

-

Ileo-ileal knot

References

Dunkerley GE. Intestinal obstruction due to knotting of two loops of small intestine. Br J Surg. 1953;41:66–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.18004116517.

Shepherd JJ. Ninety-two cases of ileosigmoid knotting in Uganda. Br J Surg. 1967;54:561–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800540615.

Taylor MW. Intestinal obstruction from a knot on the lower part of the ileum. Br Med J. 1871;2:119–21. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.552.119.

Taniguchi K, Iida R, Watanabe T, Nitta M, Tomioka M, Uchiyama K, et al. Ileo-ileal knot: a rare case of acute strangulated intestinal obstruction. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2017;79:109–13. https://doi.org/10.18999/nagjms.79.1.109.

Cowley DJ, Iweze F, Spencer J. Knotting of the small intestine. Proc R Soc Med. 1971;64:1306–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/003591577106401266.

Andromanakos N, Filippou D, Pinis S, Kostakis A. An unusual synchronous ileosigmoid and ileoileal knotting: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:200. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-8-200.

Kanamori K, Koyanagi K, Hara H, Nakamura K, Nabeshima K, Yamamoto M, et al. Small bowel obstruction caused by a true ileo-ileal knot: a rare case successfully treated by prior ligation of mesenteric vessels. Surg Case Rep. 2021;7:195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-021-01276-7.

Beg MY, Bains L, Lal P, Maranna H, Kumar NP. Small bowel knots. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2020;102:571–6. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsann.2020.0122.

Uday S, Venkata PKC, Bhargav P, Kumar S. Ileo-ileal knot causing small bowel gangrene: an unusual presentation. Int J Case. 2012;3:28–30. https://doi.org/10.5348/ijcri-2012-05-121-CR-6.

Abebe E, Asmare B, Addise A. Ileo-ileal knotting as an uncommon cause of acute intestinal obstruction. J Surg Case Rep. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjv102.

Gopivallabh MM, Jaganmaya K, Hanumanthaiah KS, Babannavar P, Crithic V. Ileoileal knot as a content of obstructed hernia: what are the odds? Iran J Med Sci. 2016;41:238–40.

Kalaichelvan DL, Perumal DSU, Ross DK, Subramanian DB. Ileo-ileal knot causing intestinal obstruction: a case report. J Dent Med Sci. 2016;15:26–9. https://doi.org/10.9790/0853-150732629.

Krishna P, Kishore A, Prasad N, Humnakar A. Rare case of acute strangulated intestinal obstruction—ileo-ileal knotting. Int J Surg Sci. 2019;3:24–5. https://doi.org/10.33545/surgery.2019.v3.i1a.08.

Rajesh A, Rengan V, Anandaraja S, Pandyaraj A. Ileo-ileal knot: a rare cause of acute intestinal obstruction. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:1661–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.14793.

Sohail M, Alyson T, Sim SK, Nik Azim NA. Intestinal knotting: a case report and brief literature review. Med J Malaysia. 2020;75:606–8.

Mohammed Y, Tesfaye K. Ileoileal knotting: a rare cause of intestinal obstruction: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15:397. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-02910-6.

Alver O, Oren D, Tireli M, Kayabaşi B, Akdemir D. Ileosigmoid knotting in Turkey. Review of 68 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:1139–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02052263.

Machado NO. Ileosigmoid knot: a case report and literature review of 280 cases. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29:402–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/0256-4947.55173.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in patient management and manuscript conception. SU and SS drafted and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was waived by the Institutional Review Board for Clinical Research, Hirosaki General Medical Center.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Umetsu, S., Shibata, S., Akasaka, H. et al. Strangulated bowel obstruction caused by an ileo-ileal knot: a rare case report. surg case rep 9, 140 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-023-01724-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-023-01724-6