Abstract

Background

Intestinal knot formation, in which two segments of the intestine become knotted together, can result in intestinal obstruction. An ileo-ileal knot refers to knot formation between two ileal segments and is a very rare benign disease. We report a case of strangulated bowel obstruction caused by true ileo-ileal knot formation.

Case presentation

An 89-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with the diagnosis of intestinal obstruction. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed the small bowel forming a closed loop, with poor contrast effect. Based on the findings, the patient was diagnosed as having strangulated bowel obstruction, and emergency surgery was performed. At laparotomy, two segments of the ileum were found to be tied together forming a knot, and both segments were necrotic. Although it was necessary to release the strangulated small bowel, we did not immediately release the knot, but first proceeded with ligation of the mesenteric vessels to the strangulated small bowel to prevent dissemination of toxic substances from the necrotic bowel into the systemic circulation. The surgery was completed with resection of the necrotic ileum and anastomosis of the small intestine. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged home.

Conclusion

We encountered a case of strangulated bowel obstruction caused by true ileo-ileal knot formation. Resection of the necrotic small intestine without releasing the knot could be performed safely, and might be considered as an option of surgical procedure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Intestinal knot formation is the condition, where two intestinal segments become tied together to form a knot, resulting in intestinal obstruction with impaired blood flow. Almost all intestinal knot formation are found between the sigmoid colon and ileum, whereas knot formation between two segments of the ileum, the so-called “ileo-ileal knot,” is rare [1]. There have been only a few reports of ileo-ileal knots, and their etiology and risks remain unclear. Herein, we report a case of strangulated bowel obstruction caused by true ileo-ileal knot formation. We then summarize the reports on ileo-ileal knots and discuss the causes, treatment details, and treatment results.

Case presentation

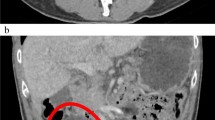

The patient was an 89-year-old woman who visited a neighborhood hospital 4 h after developing abdominal pain and vomiting of sudden onset. She was referred to our hospital 2 h later with the diagnosis of intestinal obstruction. She had a history of undergoing cesarean sections. On arrival at our hospital, her vital signs were stable; examination revealed that she was 145 cm tall and weighed 36.9 kg (calculated body mass index [BMI], 17.5). She had severe tenderness in the lower abdomen, but no signs of peritoneal irritation. Blood tests showed an elevated white blood cell count, although the serum C-reactive protein (CRP) was normal. Blood gas analysis showed mild acidosis, with a pH of 7.383, and a base excess (BE) of − 3.7. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed a small bowel forming a closed loop, with poor contrast effect, and dilatation of the oral side of the small bowel (Fig. 1a, b). Ascites was also identified (Fig. 1c). The patient was diagnosed as having strangulated bowel obstruction, and emergency surgery was performed.

At laparotomy, bloody ascites was observed. Two segments of the ileum were tied together forming a knot, and both segments were necrotic due to impaired blood flow (Fig. 2). There was a band formation between a nearby segment of the small bowel and the abdominal wall, probably attributable in part to the previous cesarean sections, but there was no evidence of intestinal obstruction. Although it was necessary to release the strangulated small bowel, we did not immediately release the knot, but first proceeded with ligation of the mesenteric vessels draining the strangulated small bowel, to prevent dissemination of toxic substances from the necrotic bowel to the systemic circulation. Ligation of the mesenteric vessels was followed by resection of a 100-cm segment of the knotted necrotic ileum, 10 cm from the ileal end. Hand-sewn anastomosis was performed with the Albert-Lembert suture. The volume of blood loss was 282 ml, and the operation time was 1 h 41 min.

The resected specimen showed the two intestinal segments wrapped together forming a knot, as indicated by the intraoperative diagnosis, and the strangulation was released by untying the knot (Fig. 3). There were no abnormalities on the mucosal surface other than signs of necrosis. Histopathological examination of the resected ileum showed that the resected small bowel was remarkably devoid of crypt epithelium, and there was severe congestion and hemorrhage extending from the intrinsic mucosal layer to the submucosa, which was considered to represent an ischemic change.

The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on the 13th postoperative day.

Discussion

Taylor et al. classified bowel knots into two types: true knots, in which one intestinal segment passes through a loop formed by another intestinal segment, and pseudo knots, in which the intestinal segments are wrapped around each other without actual formation of a knot [2]. The condition in the present case was classified as a true ileo-ileal knot, which is a rare cause of small bowel obstruction. The pathogenesis of strangulated bowel obstruction caused by pseudo knot formation is quite different from that associated with true knot formation, because adhesions are involved in the former. In this study, we focused on true knot formation, which is the narrow definition of intestinal knot formation (Fig. 4).

Intestinal obstruction caused by ileo-ileal knot formation is rare, and only 12 cases have been reported since 1990, including in the Japanese literature [1, 3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10] (Table 1). Considering the pathogenesis, the disease might be expected to be more common in older women with less visceral fat, but in the reported cases, it was also found to be quite common in younger people and in men. In almost all cases, the patients presented with abdominal pain and visited the hospital a relatively short time from the onset of the symptom. Surgery was also performed relatively early after the symptom onset, but most of the patients required small bowel resection due to intestinal necrosis. This may reflect the severe blood flow restriction caused by the knot formation. In the present case, we were able to perform surgery as early as 7 h after the symptom onset, but the small bowel was already necrotic.

Although the intestinal tract entering another intestinal loop should be free of adhesions, about a half of the previously reported cases had a previous history of laparotomy. Kondo et al. suggested that adhesions may play a role in knot formation [4]. In our case, the oral side of the intestinal segment forming the knot was fixed by adhesions, and the anal side was fixed at the ileal end. Given the high incidence of knot formation near the ileal end, partial fixation of the bowel due to adhesions may be involved in the pathogenesis of knot formation. There are reports that intestinal knot formation is more common in countries with the custom of fasting and after gastrectomy, in which it may be triggered by the large amount of food flowing into the small intestine within a short period of time [8, 11]. We hypothesized that anchorage by moderate adhesions and exaggerated intestinal peristalsis could lead to accidental knot formation.

Preoperative diagnosis of knot formation is extremely difficult, and in most previously reported cases, the condition was only diagnosed as strangulated bowel obstruction prior to the operation. CT is often not performed in patients of advanced age or cases in developing countries. In our case, preoperative CT revealed the small bowel in a closed-loop formation, and the diagnosis of strangulated bowel obstruction was made; a retrospective review, however, confirmed two, not one, closed-loop formations. As Matsuoka et al. have pointed out previously [9], the “double closed-loop” formation could be considered as a unique finding in this disease.

True ileo-ileal knot formation cannot be prevented; therefore, immediate operation is required. In terms of the most appropriate surgical procedure, there is no consensus as yet as to whether the ileo-ileal knot should be released or not before resecting the bowel. Some suggest that the knot should be released first to determine the extent of salvageable small bowel, so as to avoid excessive bowel resection [8]. In fact, in 2 reported cases, the surgery was completed simply by only releasing the knot formation. Others, however, suggest that the knot should not be released so as to prevent contamination of the operative field and entry of necrotic material into the systemic circulation [7]. In our case, the necrosis and its extent were clear, and it was possible to resect the mesentery without releasing the knot. Since ileo-ileal knot is a type of strangulated bowel obstruction that requires attention to reperfusion dysfunction, we believe that it is better to perform mesenteric ligation prior to releasing strangulation.

There were no deaths among the cases included in this review. It is considered that appropriate surgery at the right time is associated with a good prognosis.

Because of small number of reported cases, we have very limited knowledge of true ileo-ileal knot. Furthermore, almost cases were reported from Japanese institute. True pathogenesis and appropriate surgical procedure for this disease should be assessed in the near future. Considering the background of lack of understanding of the disease, our case report may be helpful to understand the therapeutic strategy of true ileo-ileal knot.

Conclusion

We encountered a case of strangulated small bowel obstruction caused by true ileo-ileal knot formation. Even though we were able to operate on the patient relatively early after the symptom onset, the involved bowel segment was found to be necrotic due to the severe blood flow restriction. Resection of the necrotic small intestine without releasing the knot might be considered as an option of surgical procedure.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CRP:

-

C reactive protein

- BE:

-

Base excess

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

References

Taniguchi K, Iida R, Watanabe T, Nitta M, Tomioka M, Uchiyama K, et al. Ileo-ileal knot: a rare case of acute strangulated intestinal obstruction. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2017;79:109–13.

Taylor MW. Intestinal obstruction from a knot on the lower part of the ileum. Br Med J. 1871;2(552):119–21.

Kusaka T, et al. A successfully trated case of ileus due to knotting of the small intestine (in Japanese). J Clin Surg. 1990;46:1929–32.

Kondo S, et al. Intestinal knotting: a clinical study of 7 cases (in Japanese). J Clin Surg. 1993;48:117–20.

Uday S, Venkata PKC, Bhargav P, Kumar S. Ileo-ileal knot causing small bowel gangrene: an unusual presentation. Int J Case Rep Imag. 2012;3:28–30.

Andromanakos N, Filippou D, Pinis S, Kostakis A. An unusual synchronous ileosigmoid and ileoileal knotting: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:200.

Abebe E, Asmare B, Addise A. Ileo-ileal knotting as an uncommon cause of acute intestinal obstruction. J Surg Case Rep. 2015;8:1–2.

Uemura J, Okano K, Wakabayashi A, Noge S, Asano E, Usuki H, et al. A surgical case of intestinal knot syndrome (true knot) (in Japanese). J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2016;36:1069–72.

Matsuoka S, Fujita K, Kikunaga H, Miura H, Kumai K. A case of bowel strangulation caused by an ileo-ileal knot (in Japanese). J Abdom Emerg Med. 2017;37:819–22.

Rajesh A, Rengan V, Anandaraja S, Pandyaraj A. Ileo-ileal knot: a rare cause of acute intestinal obstruction. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:1661–3.

Matsuzawa F, Hamaguchi J, Abe H, Suzuki T, Einama T, Kyuno K. Ileo-ileal knot causing strangulation ileus (in Japanese). J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2015;76:519–24.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in patient management and manuscript conception. KK and KK drafted the manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was waived by Institutional Review Board for Clinical Research, Tokai University.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kanamori, K., Koyanagi, K., Hara, H. et al. Small bowel obstruction caused by a true ileo-ileal knot: a rare case successfully treated by prior ligation of mesenteric vessels. surg case rep 7, 195 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-021-01276-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-021-01276-7