Abstract

Background

Delayed onset of colorectal liver metastasis (CRLM) > 5 years after primary colorectal surgery is rare. Herein, we report a case of delayed-onset CRLM that occurred 10 years after primary surgery, for which laparoscopic hepatectomy was performed.

Case presentation

A 68-year-old man was admitted to the hospital. His medical history revealed double colon cancer detected 10 years ago, for which laparoscopic colectomy was performed. The pathological tumor–node–metastasis stages were stages I and II. Thereafter, oral floor cancer occurred 7 years after the primary surgery and was curatively resected. The annual follow-up with positron emission tomography–computed tomography (CT) identified a tumor at segment 7/8 (S7/8) of the liver with an abnormal accumulation of fluorodeoxyglucose. Dynamic CT showed a 23-mm tumor, with ring enhancement in the early phase. Magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium–ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid demonstrated that the tumor had high intensity in T2 weighted sequences and low intensity in the hepatobiliary phase. With a preoperative diagnosis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or delayed liver metastasis, laparoscopic S7/8 partial resection was performed. The operative time was 324 min, and the intraoperative bleeding volume was 35 mL. The patient was discharged on day 15 without any postoperative complications. Upon histopathological examination, the final diagnosis was CRLM. The patient has survived for 1 year without any recurrence.

Conclusions

It is important to pay attention to the occurrence of delayed-metachronous CRLM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most common cancer in Japan, accounting for 16% of all new cancer diagnoses [1]. Prognosis after curative surgery for CRC has a 5-year survival rate of approximately 80% [2]. However, colorectal liver metastasis (CRLM) frequently occurs after primary resection, and the gold-standard treatment for CRLM is hepatectomy under certain conditions [3,4,5]. Perioperative systematic chemotherapy for resectable CRLM is not yet an established treatment [6]. The prognostic factors for the recurrence-free survival in patients with CRLM are preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) level, tumor diameter, tumor number, poorly differentiated primary CRC, primary lymph node metastasis, extrahepatic metastasis, and synchronous metastatic pattern [7, 8].

Most cases of CRLM are synchronously detected; however, metachronous CRLM has been reported to have an incidence of 9.4–12.9% [9, 10]. Delayed CRLM occurring 5 years after primary tumor resection has rarely been reported until now. We encountered a case of metachronous CRLM that occurred 10 years after primary tumor resection. Here, we report a case with a literature review.

Case presentation

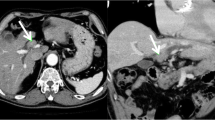

A 68-year-old man with a history of transverse colon cancer (tub2, ly1, v0, pT1N0M0 stage I) and sigmoid colon cancer (pap, ly0, v0, pT3N0M0 stage IIA) was admitted to our hospital. Curative laparoscopic surgery was performed for synchronous double colon cancer 10 years ago. Conventional surveillance was performed 5 years after the primary colon cancer. The CEA level in the fifth year was 12.6 ng/mL. His CEA level remained slightly elevated due to heavy smoking. Oral floor cancer was detected seven years after surgery. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed no space-occupying lesions in the liver. The squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) antigen was examined; however, CEA levels were not measured. Marginal mandibulectomy was performed at the Department of Otolaryngology of our hospital. The final diagnosis was SCC (pT1N0M0 stage I). After another 3 years, a liver tumor was detected during annual surveillance for oral floor cancer. Positron emission tomography–CT showed that the tumor was located on segment 7/8 (S7/8) of the liver, with an abnormal accumulation of fluorodeoxyglucose (Fig. 1). Dynamic CT showed that the tumor was 23 mm in size, with ring enhancement in the early phase (Fig. 2A). In the delayed phase, the tumor had a low-density area (Fig. 2B). Gadolinium–ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated a hyperintense lesion without central filling in T2-weighted image sequences and a hypointense lesion in the hepatobiliary phase (Fig. 3A, B). In addition to a solitary liver tumor, no extrahepatic metastases were detected. Laboratory data showed a highly elevated CEA level (29.9 ng/mL). The levels of other tumor markers, including CA19-9, α-fetoprotein, and protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist II, were within normal limits. Tumor biopsy provided a diagnosis of moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma. The preoperative differential diagnoses included delayed-onset CRLM, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and liver metastasis from oral floor cancer.

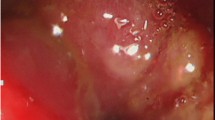

A laparoscopic S7/8 partial resection was performed. The operative time was 324 min, and the intraoperative bleeding volume was 35 mL. The histopathological diagnosis was moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma (Fig. 4). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the tumor was positive for caudal-type homeobox protein 2 (Fig. 5A) and negative for cytokeratin (CK) 7 (Fig. 5B) and CK20 (Fig. 5C). Therefore, a pathological diagnosis of CRLM was made. The patient has survived for 1 year without any recurrence.

Discussion

Most CRC recurrences occur synchronously or within 5 years of primary surgery. The distant metastatic organs were the liver, lungs, and peritoneum. The incidence of delayed distant recurrence 5 years after primary surgery for CRC was < 1% (0.63% in a Japanese study [2]). To date, five cases of delayed metachronous CRLM occurring > 5 years after primary surgery have been reported (Table 1) [11,12,13,14,15]. All patients were men, and the primary tumor was well to moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma (tub1–2) on histopathological examination. CRLM mostly occurs in the right lobe of the liver as a solitary tumor. In particular, the tumor doubling time in our case is estimated to be approximately 81 days, which was calculated based on the tumor growth. The tumor doubling time was calculated using the following formula: (day 2 value − day 1 value)/10*(logD2 − logD1), *D: diameter. Compared to 6 months prior to hepatectomy, tumor diameter had approximately doubled in size from 14 to 23 mm at the time of resection. Slow growth patterns could contribute to the good prognosis of this disease. The prognosis after hepatectomy was satisfactory, and five patients, including ours, survived without any recurrence. Notably, all cases had a relatively early tumor–node–metastasis stages (stage I or II). One report demonstrated that not only a primary tumor stage of less than stage II but also microlymphovascular invasion could be important factors for delayed local and distant metastases from CRC [15].

Whether patients with CRLM should receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC), particularly in cases of resectable CRLM, remains controversial. Some studies have reported that upfront surgery is recommended for resectable CRLM, because the prognosis of upfront surgery is equivalent to that of NAC [16, 17]. Others demonstrated that NAC could provide prognostic benefits in selected patients with bulky tumors, multiple CRLMs, and elevated CEA levels [18, 19]. Conversely, adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) after resection of CRLM is generally recommended, because ACT improves 3-year recurrence-free survival [20, 21]. In particular, ACT could provide survival benefits in selected patients with synchronous CRLM and early onset metachronous CRLM [22]. Further studies are required to establish the benefits of systemic chemotherapy in CRLM patients.

Oligometastatic surgery is effective for various types of cancer. Among them, pancreatic metastasis from renal cell carcinoma is indicated for surgical resection because of the good long-term prognosis after metastasectomy [23, 24]. Metachronous pulmonary metastasis from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and delayed-onset liver metastasis from gastrointestinal submucosal tumors are also good candidates for oligometastatic surgery [25, 26]. In the setting of pulmonary oligometastasis from colorectal cancer, surgical resection would provide a good prognosis comparable to that of liver metastasis. A long disease-free interval (≥ 36 months from primary CRC), solitary nodule, and normal pre-thoracotomy CEA level (< 5 ng/mL) are known to be independent prognostic factors [27]. Theoretically, the malignant potential of distant metastatic tumors can be dramatically lower than that of primary tumors owing to the intercellular interaction of tumor cells (seed) and the microenvironment (soil) of the metastasized organ [28, 29], a phenomenon that is supported by the well-known “seed and soil hypothesis.” Therefore, oligometastatic surgery would be beneficial, even if the primary tumor has high malignant potential.

Conclusions

We report a case of delayed-metachronous CRLM. It is important to pay attention to the occurrence of delayed-metachronous CRLM.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- ACT:

-

Adjuvant chemotherapy

- CA19-9:

-

Carbohydrate antigen 19-9

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- CK:

-

Cytokeratin

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- CRLM:

-

Colorectal liver metastasis

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- NAC:

-

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- SCC:

-

Squamous cell carcinoma

- S7/8:

-

Segment 7/8

References

Cancer Registry and Statistics. (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, National Cancer Registry). https://ganjoho.jp/reg_stat/statistics/dl/index.html#incidence. National Cancer Center, Japan: Cancer Information Service. Accessed 4 Jan 2021.

Watanabe T, Muro K, Ajioka Y, Hashiguchi Y, Ito Y, Saito Y, et al. Japanese society for cancer of the colon and rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2016 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23:1–34.

Misiakos EP, Karidis NP, Kouraklis G. Current treatment for colorectal liver metastases. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4067–75.

Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN, Ellis LM, Ellis V, Pollock R, Broglio KR, et al. Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2004;239:818–25.

Leung U, Gönen M, Allen PJ, Kingham TP, DeMatteo RP, Jarnagin WR, et al. Colorectal cancer liver metastases and concurrent extrahepatic disease treated with resection. Ann Surg. 2017;265:158–65.

Beppu T, Sakamoto Y, Hayashi H, Baba H. Perioperative chemotherapy and hepatic resection for resectable colorectal liver metastases. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2015;4:72–5.

Beppu T, Sakamoto Y, Hasegawa K, Honda G, Tanaka K, Kotera Y, et al. A nomogram predicting disease-free survival in patients with colorectal liver metastases treated with hepatic resection: multicenter data collection as a Project Study for Hepatic Surgery of the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. J Hepatobil Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:72–84.

Rees M, Tekkis PP, Welsh FK, O’Rourke T, John TG. Evaluation of long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer, a multifactorial model of 929 patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:125–35.

Scheele J, Stangl R, Altendorf-Hofmann A. Hepatic metastases from colorectal carcinoma: impact of surgical resection on the natural history. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1241–6.

Wade TP, Virgo KS, Li MJ, Callander PW, Longo WE, Johnson FE. Outcomes after detection of metastatic carcinoma of the colon and rectum in a national hospital system. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;182:353–61.

Yukawa N, Rino Y, Sugano N, Yamada R, Sato T, Inagaki D, et al. An elder patient case of laparoscopic partial hepatectomy for metachronous liver metastasis of rectal cancer at five years after laparoscopic anterior resection. J Jpn Coll Surg. 2012;37:990–6.

Takabayashi K, Sumiyama Y, Watanabe M, Asai K, Saida Y, Takahashi K. A case of submucosal invasive colon cancer that developed metastatic hepatic cancer eight years after the surgery. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2007;68:2288–92.

Washida M, Nishihira T, Kaneko T, Ishii T, Iwai A, Inoue A. A resected case of liver metastasis from colon cancer causing ileus by direct invasion occurred 9 years and 4 months after a colectomy. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2002;63:426–9.

Ogura T, Sakamoto H, Kikuchi I, Yatsuoka T, Amikura K, Oba H, et al. A case of liver metastasis resected by laparoscopic hepatectomy seven years after primary sigmoid cancer surgery. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2015;76:577–82.

Kanomata H, Ushimado K, Tachikawa N, Shimizu Y, Shatari T, Furuuchi T. A resected case of liver metastasis 11 years after excision of rectosigmoid colon cancer. J Clin Surg. 2015;70:1151–5.

Hirokawa F, Asakuma M, Komeda K, Shimizu T, Inoue Y, Kagota S, et al. Is neoadjuvant chemotherapy appropriate for patients with resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer? Surg Today. 2019;49:82–9.

Pandanaboyana S, White A, Pathak S, Hidalgo EL, Toogood G, Lodge JP, et al. Impact of margin status and neoadjuvant chemotherapy on survival, recurrence after liver resection for colorectal liver metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:173–9.

Liu W, Zhou JG, Sun Y, Zhang L, Xing BC. The role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for resectable colorectal liver metastases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2016;7:37277–87.

Zhu D, Zhong Y, Wei Y, Ye L, Lin Q, Ren L, et al. Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastases. PLoS ONE. 2014;9: e86543.

Hasegawa K, Saiura A, Takayama T, Miyagawa S, Yamamoto J, Ijichi M, et al. Adjuvant oral uracil-tegafur with leucovorin for colorectal cancer liver metastases: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2016;11: e0162400.

Mitry E, Fields AL, Bleiberg H, Labianca R, Portier G, Tu D, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy after potentially curative resection of metastases from colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of two randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4906–11.

Kobayashi S, Beppu T, Honda G, Yamamoto M, Takahashi K, Endo I, et al. Survival benefit of and indications for adjuvant chemotherapy for resected colorectal liver metastases—a Japanese nationwide survey. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:1244–60.

Zerbi A, Ortolano E, Balzano G, Borri A, Beneduce AA, Di Carlo V. Pancreatic metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: which patients benefit from surgical resection? Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1161–8.

Fikatas P, Klein F, Andreou A, Schmuck RB, Pratschke J, Bahra M. Long-term survival after surgical treatment of renal cell carcinoma metastasis within the pancreas. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:4273–8.

Downs-Canner S, Zenati M, Boone BA, Varley PR, Steve J, Hogg ME, et al. The indolent nature of pulmonary metastases from ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112:80–5.

Matsuoka L, Stapfer M, Mateo R, Jabbour N, Naing W, Selby R, et al. Left extended hepatectomy for a metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor after a disease-free interval of 17 years: report of a case. Surg Today. 2007;37:70–3.

Salah S, Watanabe K, Welter S, Park JS, Park JW, Zabaleta J, et al. Colorectal cancer pulmonary oligometastases: pooled analysis and construction of a clinical lung metastasectomy prognostic model. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2649–55.

Grassi P, Doucet L, Giglione P, Grünwald V, Melichar B, Galli L, et al. Clinical impact of pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: a multicenter retrospective analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11: e0151662.

Chambers AF, Groom AC, MacDonald IC. Dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:563–72.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding body was involved in the design of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; and writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HS and TA conceived the idea, developed the theory, and performed the computations. AO, YS, HO, MK, SY, TK, HO, TN, and MN encouraged the investigation of specific aspects and supervised the findings of this study. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of our institution approved all procedures used in this study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shidahara, H., Abe, T., Oshita, A. et al. Metachronous colorectal liver metastasis that occurred 10 years after laparoscopic colectomy: a case report. surg case rep 8, 144 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-022-01503-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-022-01503-9