Abstract

Background

In situ cholangiocarcinoma is difficult to detect by imaging studies. Thus, cholangiocarcinoma is rarely resected with a preoperative definitive diagnosis, especially nonpapillary flat type in situ carcinoma, which is extremely rare.

Case presentation

A 70-year old man was diagnosed with gallbladder cancer and received open cholecystectomy with lymphadenectomy at a local hospital. Histologically, the tumor was localized in the mucosal layer, and no lymph node metastases were found. Three months later, hilar bile duct stricture due to delayed bile duct ischemia was found. Then, biliary drainage was performed with endoscopic biliary stenting. Three months later, the patient experienced cholangitis with septic shock, and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) into the left intrahepatic bile duct was performed. Unexpectedly, the aspiration bile cytology of the PTBD catheter showed malignant cells, and the patient was referred to our clinic for possible surgical treatment. According to additional studies, the hilar bile duct stricture was 3 cm in length. None of the imaging studies detected malignant cells in the bile duct around the hilar stricture. The left portal vein was obstructed due to inadvertent puncture of the PTBD. No findings indicated cholangiocarcinoma. We performed left hepatectomy with caudate lobectomy and extrahepatic bile duct resection. The postoperative course was uneventful. In the final pathology, flat type in situ carcinoma was found at the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts, which was distant from the biliary stricture.

Conclusions

When a tumor is undetectable but cytology is positive, in situ cholangiocarcinoma may exist; thus, surgery should be carefully considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In situ cholangiocarcinoma, i.e., epithelial carcinoma without submucosal invasion, is asymptomatic and very difficult to detect by multidetector-row computed tomography (MDCT) or direct cholangiography. Thus, this type of carcinoma is rarely resected with a preoperative definitive diagnosis, especially, nonpapillary flat type in situ carcinoma, which is extremely rare.

Here, we present a case of flat type in situ perihilar cholangiocarcinoma that was incidentally accompanied by hilar bile duct stricture after open cholecystectomy. Preoperative diagnostic imaging studies did not identify the lesion, and only aspiration bile cytology showed a positive result.

Case presentation

A 70-year old man was diagnosed with gallbladder cancer (Fig. 1a) and received open cholecystectomy with lymphadenectomy of the hepatoduodenal ligament at a local hospital. The final pathology showed that the tumor was a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with an invasion depth of the mucosal layer. No lymph node metastases were found, and all of the surgical margins were negative (Fig. 1b). The patient was discharged from the hospital, but 3 months later, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed hilar bile duct stricture with intrahepatic biliary dilatation (Fig. 2a), probably due to delayed bile duct ischemia caused by lymphadenectomy. Then, biliary drainage was performed with endoscopic biliary stenting (Fig. 2b). Three months later, the patient experienced cholangitis with septic shock, and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) into the left intrahepatic bile duct was performed (Fig. 2c). Unexpectedly, the aspiration bile cytology from the PTBD catheter showed malignant cells (Fig. 2d). Percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy (PTCS) was performed via the sinus tract of PTBD, but the examination failed to detect any malignant lesions in the biliary tree. The patient was referred to our clinic for possible surgical treatment.

Images of the bile stricture. a MRCP showing a hilar bile duct stricture (yellow arrowheads). b Endoscopic biliary stent placed in the right posterior inferior bile duct (B6). c Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage into the left lateral anterior bile duct (B3). d Aspiration bile cytology from the PTBD showing malignant cells. MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; CBD, common bile duct; PTBD, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage

After admission, the patient’s cholangiograms were re-evaluated (Fig. 3a, b). The right posterior inferior bile duct (B6) was the infraportal type and joined the common hepatic duct. The hilar bile duct stricture was 3 cm in length. Intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS) did not detect any malignant cells in the bile duct around the hilar stricture, and no cancer cells were found in the endoscopic biopsy specimen. MDCT demonstrated a left portal vein obstruction, probably due to the inadvertent puncture of PTBD performed at the local hospital. Overall, no findings that indicated cholangiocarcinoma were observed. However, we determined that surgery was needed to treat this complicated biliary stricture. Left hepatectomy with caudate lobectomy and extrahepatic bile duct resection was performed. Severe adhesion around the hepatoduodenal ligament resulted in a difficult surgery. Intraoperative frozen section examination revealed no malignancy of the resected common bile duct stump and biliary stricture. The stumps of the resected B6 and the right hepatic duct were reconstructed by Roux-en-Y cholangiojejunostomy (Fig. 3c). The operative time was 591 min, and blood loss was 1745 ml.

Cholangiogram, preoperative schema, and operative picture. a Cholangiogram showing a hilar bile duct stricture (orange arrow). b Preoperative scheme. The planned surgery was left hepatectomy with caudate lobectomy. c Left hepatectomy with en bloc resection of the caudate lobe and extrahepatic bile duct was performed as scheduled. The right hepatic duct (RHD) and the right posterior inferior bile duct (B6a) were reconstructed separately

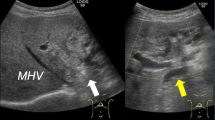

The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 12. In the final pathology, no malignant cells were observed in the hilar stricture, but flat type in situ carcinoma was found at the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts, which was distant from the stricture (Fig. 4). Histologically, the carcinoma was a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma and 1 cm in diameter. No lymph node metastases were found, and all of the surgical margins were negative. There were no BilIN lesions in the background bile duct. The patient is still alive and in good health 54 months after the hepatectomy.

Discussion

When arterial blood flow to the bile duct is restricted, a bile duct stricture will develop [1, 2]. Several authors have reported delayed bile duct strictures due to ischemia after excision of the tissue surrounding the biliary tree [3,4,5]. Ishizuka et al. [3] reported two cases of delayed ischemic biliary stricture after radical lymphadenectomy in the hepatoduodenal ligament with skeletonization of the extrahepatic bile ducts for malignant diseases: in both cases, histologic examination of the subsequently resected biliary strictures revealed evidence of ischemia. Skeletonization of the extrahepatic bile duct may induce ischemia then delayed stricture formation. Lymphadenectomy of the hepatoduodenal ligament is routinely performed in advanced gallbladder carcinoma. However, when preserving the extrahepatic bile duct, this surgical procedure may induce bile duct stricture, and the present case is a case of delayed ischemic stricture. For prevention of this complication, assessment of arterial perfusion in the bile duct wall using indocyanine green near-infrared imaging may be a promising way [5].

Flat type precursor lesions are called biliary intraepithelial neoplasias and are classified into three grades [6]. Especially with severe atypia, the lesions are identical to in situ carcinoma. This kind of epithelial carcinoma is often detected as a lesion accompanied by invasive carcinoma [7], while in situ carcinoma alone is rarely detected. According to our previous study [8], only 3 cases of in situ carcinoma were found in 545 consecutive resections of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Thus, the incidence of in situ perihilar cholangiocarcinoma was 0.55%.

In this case, aspiration bile cytology alone showed a positive result. We performed aspiration cytology from the PTBD catheter five times, which was positive three times. Tsuchiya et al. [9] reported that the positivity of aspiration bile cytology increased when repeatedly performed but reached a plateau after five examinations. Aspiration cytology is easy to perform and repeatable [10]; thus, it should be used, especially in cases of negative biopsy results. However, aspiration cytology never indicates location of the lesion, which is a major limitation of this examination.

Conclusions

We experienced a rare case of flat type in situ perihilar cholangiocarcinoma that was incidentally accompanied by a benign bile duct stricture. When the tumor is undetectable but aspiration cytology is positive, in situ cholangiocarcinoma may exist; thus, surgery should be carefully considered.

Availability of data and materials

The authors declare that all data in this article are available within this published article.

Abbreviations

- CBD:

-

Common bile duct

- ENBD:

-

Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage

- IDUS:

-

Intraductal ultrasonography

- MDCT:

-

Multidetector-row computed tomography

- PTBD:

-

Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage

- PTCS:

-

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy

References

Makuuchi M, Sukigara M, Mori T, Kobayashi J, Yamazaki S, Hasegawa H, et al. Bile duct necrosis: complication of transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization. Radiology. 1985;156(2):331–4.

Colonna JO 2nd, Shaked A, Gomes AS, Colquhoun SD, Jurim O, McDiarmid SV, et al. Biliary strictures complicating liver transplantation. Incidence, pathogenesis, management, and outcome. Ann Surg. 1992;216(3):344–50 discussion 50-2.

Ishizuka D, Shirai Y, Hatakeyama K. Ischemic biliary stricture due to lymph node disection in the hepatoduodenal ligament. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45(24):2048–50.

Jung DH, Hwang S, Ha TY, Song GW, Kim KH, Ahn CS, et al. Long-term outcome of ischemic type biliary stricture after interventional treatment in liver living donors: a report of two cases. Korean J of Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2015;19(2):71–4.

Sakata K, Kijima D, Furuhashi T, Morita K, Abe T. A case report: feasibility of a near infrared ray vision system (photo dynamic eye(R)) for the postoperative ischemic complication of gallbladder carcinoma. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;53:312–5.

Zen Y, Aishima S, Ajioka Y, Haratake J, Kage M, Kondo F, et al. Proposal of histological criteria for intraepithelial atypical/proliferative biliary epithelial lesions of the bile duct in hepatolithiasis with respect to cholangiocarcinoma: preliminary report based on interobserver agreement. Pathol Int. 2005;55(4):180–8.

Ainechi S, Lee H. Updates on precancerous lesions of the biliary tract: biliary precancerous lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(11):1285–9.

Shinohara K, Ebata T, Shimoyama Y, Nakaguro M, Mizuno T, Matsuo K, et al. Proposal for a new classification for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma based on tumour depth. Br J Surg. 2019;106(4):427–35.

Tsuchiya T, Yokoyama Y, Ebata T, Igami T, Sugawara G, Kato K, et al. Randomized controlled trial on timing and number of sampling for bile aspiration cytology. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21(6):433–8.

Davidson B, Varsamidakis N, Dooley J, Deery A, Dick R, Kurzawinski T, et al. Value of exfoliative cytology for investigating bile duct strictures. Gut. 1992;33(10):1408–11.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank American Journal Experts (www.aje.com) for the English language editing.

Funding

The authors declare that they received no financial support pertaining to this case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MN, NW, MN, and KS performed the surgery and perioperative management on the patient, and MN drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Maeda, T., Ebata, T., Yokoyama, Y. et al. A case of small in situ perihilar cholangiocarcinoma incidentally accompanied by benign bile duct stricture after open cholecystectomy. surg case rep 5, 177 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-019-0745-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-019-0745-z