Abstract

Background

A brachial artery aneurysm (BAA) is a rare condition accounting for 5% of all peripheral arterial aneurysms. More cases of true BAAs after arteriovenous fistula (AVF) closure have been reported in the past two decades.

Case presentation

A 60-year-old man who underwent AVF closure after renal transplantation had a true BAA on his left elbow that had grown within the past 6 months. We successfully performed an open repair with end-to-end anastomosis. No complications occurred for 1 year.

Conclusions

High flow due to AVF and some collateral factors such as the use of steroids and immunosuppressants after renal transplantation, arteriosclerosis, and chronic mechanical stimulation might contribute to BAA formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A brachial artery aneurysm (BAA) is a rare condition accounting for 5% of all peripheral arterial aneurysms [1]. Most BAAs are pseudoaneurysms caused by trauma or iatrogenic complications [2, 3]; true BAAs are quite rare. The main etiologies of true BAAs are blunt trauma, atherosclerosis, infection, and vasculitis, and more than 50% of all patients with true BAAs have a history of blunt trauma [2]. A recently reported rare cause of true BAAs is arteriovenous fistula (AVF) closure after hemodialysis or renal transplantation [4, 5]. High flow due to AVF and essential drugs after transplantation, steroids, and immunosuppressants can also cause BAAs [4, 5]. The standard treatment for BAAs remains controversial because of their rarity and thus lack of detailed information.

This report describes a case of a true BAA after AVF closure following renal transplantation. The BAA was treated by excision and end-to-end brachial artery reconstruction. We also reviewed cases of idiopathic true BAAs and evaluated the etiology and optimal treatment for true BAAs.

Case presentation

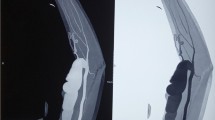

A 60-year-old Japanese man presented with a left brachial mass that had developed during the past 6 months. The mass was 3.5 cm in size, pulsatile, and unaccompanied by pain, tenderness, or skin symptoms. The patient had started hemodialysis 27 years previously from a radiocephalic AVF on the left arm. He underwent cadaveric renal transplantation 15 years previously and had been administered immunosuppressive and steroid therapy (tacrolimus at 4 mg/day and prednisolone at 5 mg/day) to prevent renal rejection. The AVF was closed 4 years after renal transplantation. A BAA was diagnosed by enhanced computed tomography (CT), which showed a 35-mm-diameter fusiform BAA (Fig. 1c, d). Although an intraluminal thrombus was observed at the BAA, the distal blood flow was preserved.

The patient underwent aneurysm resection and open surgical revascularization because the aneurysm had gradually increased in size and limited the joint mobility. Under general anesthesia, the patient underwent excision of the BAA and end-to-end brachial artery reconstruction with 6–0 polypropylene sutures (Fig. 2a, b). The operative period was 1 h 21 min, and blood loss was minimal. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged 8 days postoperatively. The aneurysm was characterized by thickened vessel walls, and thrombosis was found in the lumen (Fig. 2c). Pathological examination showed a thickened tunica externa and thinned tunica intima and media. Internal elastic lamina was thinning and partially vanished but a three-layer structure was well-maintained (Fig. 2d, e); therefore, the BAA was diagnosed as a true aneurysm. It did not reveal typical arteriosclerotic. The patient was in good condition without recurrent symptoms 1 year postoperatively.

Discussion

We have herein reported a true BAA following AVF closure after renal transplantation. The patient was treated by excision of the BAA and end-to-end brachial artery reconstruction.

Most true BAAs are caused by blunt trauma, atherosclerosis, infection, and vasculitis [2]. Regarding our patient, atherosclerosis might affect the formation of aneurysm, but it is not certain (pathological examination did not reveal typical arteriosclerotic, but CT findings showed the severe arteriosclerotic change in the abdominal aorta) and other histories of trauma or iatrogenic puncture ware absence. This idiopathic case without typical medical history is quite rare.

We searched PubMed for cases of true BAA using the keyword “true brachial artery aneurysm.” This search produced detailed reports of idiopathic true BAAs in 48 adults (Table 1). The patients’ mean age was 53.7 years (n = 46). Approximately 85% of the patients were men (39/46). The mean maximum diameter of the BAAs was 4.8 cm (n = 46). Interestingly, 41 patients (85%) had a medical history of AVF creation. Eugster et al. [6] said AVF side brachial artery generally expand after AVF creation and increases the blood flow of the brachial artery. The high flow increased shear forces which induced transverse tears in the elastic fibers of internal elastic membrane [7, 8]. And more, at the molecular level, active metabolism due to high flow and stress causes endothelial cells to produce superoxide ions and nitric oxide; these in turn form peroxynitrates that stimulate metalloproteinase, which breaks down the extracellular matrix and injures the internal elastic lamina [4, 5, 9, 10]. In fact, 3-D CT showed expanded left brachial artery which indicates high flow and pathological examination revealed internal elastic lamina was thinning and partially vanished.

In addition to this, some collateral factors might contribute to the aneurysm formation. One was steroids and immunosuppressants’ use after renal transplantation. According to our review, 22 patients (46%) underwent AVF closure after renal transplantation. Generally, steroids are suggested to promote the formation and enlargement of arterial aneurysms [11]. They not only impair glucose tolerance and exacerbate arteriosclerosis, thus indirectly promoting aneurysm formation, but also directly cause tissue fragility that mainly affects small- to medium-sized arteries [12]. Immunosuppressants are also suggested to provide a synergistic effect on the damage caused by steroids [12]. In our case, the patient underwent renal transplantation and began treatment with a steroid (prednisolone at 5 mg/day) and immunosuppressant (tacrolimus at 4 mg/day) 15 years before the emergence of the BAA. Another factor was arteriosclerotic. The pathological examination did not reveal typical arteriosclerotic change, but CT findings showed the severe arteriosclerotic change in the abdominal aorta, so it was very likely that the brachial artery got some arteriosclerotic effect and damaged. And more, Marconi et al. [13] and Nishimura et al. [14] reported true BAA located near the elbow like our case. Chronic mechanical stimulation, an elbow joint movement might also promote damages to the brachial artery.

Although BAAs are rare, it is often difficult to determine whether a BAA itself is symptomatic because 33% of BAAs are associated with complications such as pain, edema, neuropathy, distal limb ischemia, and aneurysm rupture [2]. In the present review, only 7 patients (15%) were asymptomatic or showed only a swelling mass. Importantly, 12 of 13 relatively small aneurysms (< 35 mm) were symptomatic, and the size of the aneurysm did not seem to be correlated with the patient’s symptoms. Pain was the most frequent symptom (56%, 27/48), and thrombi/emboli and paresthesia were found in 29% (14/48) and 8% (4/48) of patients, respectively. Although our review did not include cases of rupture, rupture of a BAA can be an indication for upper limb amputation [15]. Fundamentally, therefore, BAAs should be treated independent of size, and careful follow-up is required when an observation is selected.

With respect to treatment, 47 patients (97%) in our review underwent surgical treatment (Table 1). Surgical treatment is often selected because the stenting of joints, including the elbow, is not favorable. Interposition with a native vessel graft was widely applied (75%, 36/48), and the great saphenous vein was used in most cases. In case of not available of saphenous vein, femoral vein or polytetrafluoroethylene was used. However, the use of conduit has some risk such as graft occlusion or size mismatch between the host artery and graft [4]. End-to-end anastomosis can be a more physiological and safe brachial artery reconstruction technique. Further studies are required to reveal the detailed pathology and optimal management of BAAs following AVF closure after renal transplantation.

Conclusion

High flow due to AVF and some collateral factors such as the use of steroids and immunosuppressants after renal transplantation, arteriosclerosis, and chronic mechanical stimulation might contribute to true BAA formation. Careful follow-up is desirable for such a case.

Availability of data and materials

None (because our manuscript is a case report).

Abbreviations

- AVF:

-

Arteriovenous fistula

- BAA:

-

Brachial artery aneurysm

References

Schunn CD, Sullivan TM. Brachial arteriomegaly and true aneurysmal degeneration: case report and literature review. Vasc Med. 2002;7:25–7.

Gray RJ, Stone WM, Fowl RJ, et al. Management of true aneurysms distal to the axillary artery. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28:606–10.

Yetkin U, Gurbuz A. Post traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the brachial artery and its surgical treatment. Tex Heart Inst J. 2003;30:293–7.

Ferrara D, Di Filippo M, Spalla F, et al. Giant true brachial artery aneurysm after hemodialysis fistula closure in a renal transplant patient. Case Rep Nephrol Dial. 2016;6:128–32.

Dinoto E, Bracale UM, Vitale G, et al. Late, giant brachial artery aneurysm following hemodialysis fistula ligation in a renal transplant patient: case report and literature review. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;60:768–70.

Eugster T, Wigger P, Bolter S, et al. Brachial artery dilatation after arteriovenous fistulae in patients after renal transplantation: a 10-year follow-up with ultrasound. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:564–7.

Nyugen DQA, Ruddle AC, Thompson JF. Late axillo-brachial arterial aneurysm following ligated Brescia-Cimino haemodialysis fistula. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2001;22:381–2.

Murphy J, Bakran A. Late, acute presentation of a large brachial artery aneurysm following ligation of a Brescia-Cimino arteriovenous fistula. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:123.

Basile C, Antonelli M, Libutti P, et al. Is there a link between the late occurrence of a brachial artery aneurysm and the ligation of an arteriovenous fistula? Semen Dial. 2011;24:341–2.

Chung AW, Yang HH, Kim JM, et al. Upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in the arterial vasculature contributes to stiffening and vasomotor dysfunction in patients with chronic kidney disease. Circulation. 2009;120:792–801.

Sato O, Atsuhiko T, Tetsuro M, et al. Aortic aneurysm in patients with autoimmune disorders treated with corticosteroids. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1995;10:366–9.

Tajima Y, Goto H, Ohara M, et al. Oral steroid use and abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion – positive association. Circ J. 2017;81:1774–82.

Marconi M, Adami D. Giant true brachial artery aneurysm after hemodialysis fistula closure. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49:531.

Nishimura K, Hamasaki T, Fukino S. A case of true brachial artery aneurysm with severe left upper limb ischemia. Int J Angiol. 2016;25:180–2.

Panagiotopoulos E, Athanaselis E, Matzaroglou C, et al. Compound and acutely ruptured false aneurysm of the brachial artery. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:6627.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ST and KI contributed to the study conception. ST and KM contributed to the data collection. ST and KI contributed to the writing. SK, SY, KN, SY, MK, TF, and YM contributed to the critical review and revision. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors approved the final article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

References for the literature review.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Toyota, S., Inoue, K., Kurose, S. et al. True brachial artery aneurysm after arteriovenous fistula closure following renal transplantation: a case report and literature review. surg case rep 5, 188 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-019-0724-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-019-0724-4