Abstract

Background

Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) of the bile duct is extremely rare and is a high-grade type of neuroendocrine tumor with an aggressive clinical course. Here, we report a case of LCNEC of the extrahepatic bile duct.

Case presentation

An 80-year-old man presented with severe jaundice. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and enhanced computed tomography revealed complete obstruction of the common bile duct (CBD) by a dense tumor measuring 1.5 cm in diameter. Although there were no malignant cells in the biliary brush cytology, we suspected a cholangiocarcinoma and performed extrahepatic bile duct resection. Histologically, the LCNEC occupied most of the places deeper than the stratum submucosum and an adenocarcinoma component, approximately 15%, was present in the mucosa. There were no transitional areas between the two components. Immunohistochemically, the LCNEC cells were reactive for CD56 and synaptophysin and had a high MIB-1 index (72%). The patient died of multiple liver, lung, and peritoneal metastases 3 months after surgery.

Conclusions

LCNEC of the CBD is particularly rare and has a very poor prognosis. Only five cases have been reported in the literature; therefore, there is no established effective therapy, including surgery, for LCNEC of the CBD at present. An accumulation of additional cases and further studies of multimodal treatment are required in the future to improve the prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Primary neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) of the common bile duct is rare, and only 27 cases have been reported in the literature so far. One type of NEC, large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC), is particularly rare, and only five cases have been previously reported. Here, we report a case of LCNEC of the extrahepatic bile duct and a review of the literature.

Case presentation

An 80-year-old man presented to our hospital with anorexia and jaundice that had been present for several weeks. The patient had neither abdominal tenderness nor a palpable mass in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. He underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection for multiple early gastric cancers 1 year ago, and all of the lesions were resected radically. He had severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease because of long-term smoking. The patient’s main occupation was in agriculture, and he had never worked in the printing or staining industries. The patient had no family history of cancer.

On the day of admission, his complete blood count and serum biochemical parameters were as follows: white blood cells, 10.5 × 103/μL (normal range 3.3–9.0 × 103/μL); red blood cells, 28.5 × 106/μL (4.3–5.7 × 106/μL); hemoglobin, 9.2 g/dL (13.5–17.5 g/dL); total protein, 5.0 g/dL (6.7–8.3 g/dL); albumin, 1.5 g/dL (4.0–5.0 g/dL); total bilirubin, 26.0 mg/dL (0.3–1.1 mg/dL); direct bilirubin, 17.0 mg/dL (0.1–0.5 mg/dL); aspartate aminotransaminase, 91 IU/L (normal 10–40 IU/L); alanine aminophosphatase, 90 IU/L (5–45 IU/L); aspartate transferase, 1560 IU/L (100–325 IU/L); and gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase, 278 IU/L (7–80 IU/L). His carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) was 40,635 U/mL (0–37 U/mL), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was 10.4 ng/mL (0–5.0 ng/mL). Alpha fetoprotein levels were within normal limits.

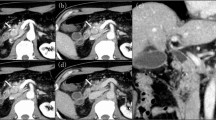

An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed an enhanced mass that was approximately 2.5 cm in size located in the mid common bile duct (CBD) and an enlarged regional node in the hepatoduodenal ligament (Fig. 1a). 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) revealed high accumulation of FDG with a maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 20.7 by the CBD tumor (Fig. 1b).

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrated severe intrahepatic bile duct dilatation and a filling defect in the mid-CBD. The tumor was involved with the cystic duct. After the ERCP, endoscopic placement of a nasobiliary biliary drainage catheter was performed (Fig. 2). The bile and brush cytology performed at the same time revealed a few degenerative atypical cells (class 3).

The patient underwent surgery with the presumed diagnosis of bile duct cancer. The operative method was extrahepatic bile duct resection with lymph node dissection and reconstruction with a Roux en Y hepaticojejunostomy because of his advanced age and severe pulmonary emphysema. The 18 regional lymph nodes were resected. The right hepatic artery was fixed to the tumor, and we performed a complicated resection. There was evidence of local cancer invasion, but no signs of distant metastasis or organ invasion were noted. The resection margins of the proximal and distal bile duct frozen biopsy were tumor free. Peritoneal lavage cytology during the operation was negative.

Macroscopically, the surgical specimen showed a light gray invasive nodular tumor measuring 2.4 × 1.9 cm located in the mid-CBD (Fig. 3a). The sectioned surface of the resected specimen showed tumor invasion beyond the bile duct serosa (Fig. 3b). There were no gallstones in either the gallbladder or bile ducts.

Formalin-fixed surgical specimen. a The surgical specimen showed a tumor measuring 2.4 × 1.9 cm located in the mid-CBD (arrow). b The sectioned surface (at #1 and #2 of Fig. 1) of the resected specimen showed tumor invasion beyond the bile duct serosa

On histopathological examination of the resected specimen stained with hematoxylin and eosin, the tumor was structured with two components (Fig. 4a). There was no transitional area between the two components. High cellularity components made up approximately 90% of the tumor and exhibited invasion throughout the entire CBD wall with serosal penetration (Fig. 4b). The other component was tubular adenocarcinoma, and it occupied a small area of the tumor in the superficial mucosal portion (Fig. 4c). In the LCNEC area, the tumor was solid and cellular with necrosis inside. There was no differentiation into duct structures. The tumor cells were joined together, and the cells, nucleus, and cytoplasm were relatively large (Fig. 4d). A high-power image of d shows that the tumor cells were large idioblasts and the nucleolus was clear. Each nucleus variant was strong, and the heteromorphic nuclei division image was obvious (Fig. 4e).

Pathologic examination of the resected specimen stained with hematoxylin and eosin. a Loupe image of the tumor revealed invasion throughout the entire CBD wall with serosal penetration. b Magnification of the part in the square in a. The tumor was structured with two components (black and white arrows). There was no transitional area between the two components. c Intermediate-magnification image of the part marked with a black arrow showed moderate differentiated adenocarcinoma. d The intermediate-magnification image of the part marked with a white arrow shows LCNEC, which made up approximately 90% of the tumor. The tumor was solid and cellular with necrosis inside. The tumor cells were joined together, and the cytoplasm was relatively large. e A high magnification of d shows that each nucleus variant was large and the heteromorphic nuclei division image was obvious

Immunohistochemical findings in the LCNEC component indicated that the tumor cells were immunopositive for neuroendocrine markers, including synaptophysin and CD56, but were negative for chromogranin A and neurospecific enolase (NSE) (Fig. 5a–c). Immunostaining for Ki-67 showed a strong positive of 72% (Fig. 5d). Immunohistochemical findings in the adenocarcinoma component indicated that the tumor cells were not immunopositive for neuroendocrine markers (Fig. 6a–c). There were no transitional areas between the components. Staining for Ki-67 showed mild positive at 27% (Fig. 6d). Metastases from the LCNEC were noted in two of the 18 lymph nodes. The metastatic lymph nodes were in contact with the tumor.

Immunohistochemical findings in the component of LCNEC. a Immunostaining for synaptophysin was partially positive. b Immunostaining for chromogranin A was negative. c Immunostaining for CD56 was strongly positive in most of the LCNEC cells. d Immunostaining for Ki-67 was strongly positive in 72% of the LCNEC cells

Immunohistochemical findings in the component of adenocarcinoma. There were no immunopositive cells in the adenocarcinoma component. a Immunostaining for synaptophysin was negative. b Immunostaining for chromogranin A was negative. c Immunostaining for CD56 was negative. d Immunostaining for Ki-67 showed diffused positivity in 27% of the adenocarcinoma cells

No postoperative complications occurred, and the patient was discharged. His CEA and CA19-9 levels normalized after the operation.

The patient had peritoneal metastases develop during the early postoperative period, and a postoperative CT only 2.5 months later showed a lung metastasis and multiple liver metastases occupying half of the liver. The patient died 3 months after surgery.

Discussion

In the World Health Organization classification, neuroendocrine neoplasms are classified into five general categories, including neuroendocrine tumor (NET), NEC, mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma (MANEC), goblet cell carcinoid, and tubular carcinoid. In addition, NECs are classified as either LCNEC or small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SCNEC) [1]. When each component is more than 30% of the tumor, it is defined as MANEC.

The bile ducts are one of the rarest primary organs for NET, accounting for only 0.2 to 2.0% of all such tumors [2]. NEC arising in the extrahepatic bile duct includes pure NEC, MANEC, and NEC with adenocarcinoma, but only 27 cases have been described previously in the literature [3–29] (Table 1). Of these, 19 cases were pure NEC and eight cases were composite glandular–endocrine cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Most of these cases (82%) were SCNEC, and LCNEC was extremely rare, only five cases. Sato et al. first reported LCNEC with adenocarcinoma in the CBD in 2006 [16], and thus, our case becomes the sixth report of LCNEC arising in the extrahepatic bile duct.

Sasatomi (2013), Ninomiya (2013), and Park (2014) reported cases of pure LCNEC in the CBD [26–28]. From what can be analyzed from the literature, the mean tumor diameter was 3.5 cm (range 0.3–6.5 cm), median survival time was 12.0 months (range 0.7–45 m), and the 1-year survival rate was 32.6%. In 84% of cases, radical resection was performed.

The pathological fact that normal bile duct mucosa does not have neuroendocrine cells was cited as one of the reasons why a primary NEC of the CBD is extremely rare. Harada et al. examined 274 cases of biliary cancer and reported that MANET was found in 4% of hepatic hilar cholangiocarcinomas with hepatolithiasis, 10% of gallbladder cancers, and 4% of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas [30]. The authors of this report expressed the opinion that normal adenocarcinoma developed during a process of growth and dedifferentiation to endocrine cells. Albores et al. reported that neuroendocrine cells could be detected at sites of intestinal metaplasia induced by chronic inflammation due to cholelithiasis and congenital anomalies, which might be the initial step in the development of neuroendocrine tumors of the CBD [31]. The process suggested this report was one reason why pure NET and NEC developed. Although pure NET cases without dysplastic intestinal-type epithelium exist, they seem to follow a different developmental process.

LCNEC of the CBD is a poorly differentiated and rare tumor that exhibits high-grade NET with aggressive behavior and has a strong tendency to develop early lymph node and distant metastases. The survival duration of previously reported cases of LCNEC of the CBD ranged from only 21 days to 12 months after surgery (Table 1). In our case, the recurrence was noted 2.5 months after surgery, and the patient died 3 weeks after the recurrence. The prognosis of LCNEC is extremely poor in comparison with adenocarcinoma of the same clinical stage, even if we can resect the tumor radically.

In this case, we chose to perform extrahepatic bile duct resection, which is not commonly used. In cases of extrahepatic bile duct cancer with obstruction of the cystic duct, we usually perform subtotal stomach-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy because of metastasis of lymph nodes around the head of the pancreas and direct invasion to the pancreatic parenchyma. Because the patient was 80 years old and had progressive dementia and severe pulmonary emphysema, once the resection margin of the distal CBD frozen biopsy was tumor free, with the consent of his family, we decided to defer pancreatoduodenectomy. We do not believe that this reduction surgery caused early postoperative liver metastasis.

Adjuvant chemotherapy in three cases of LCNEC of the CBD was reported previously [16, 24, 27], and these patients survived 3 to 12 months. Yamaguchi et al. reported that adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine could not suppress the recurrence, but hepatic artery infusion with CPT-11 (40 mg/kg body weight) and CDDP (20 mg/kg body weight) every 2 weeks remarkably decreased tumor markers and the size of both lymph nodes and liver tumors [23].

At present, it is controversial whether a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy is more effective than resection alone [17, 22]. In this case, we could not provide adjuvant chemotherapy because of the general poor condition of the patient. Because peritoneal, lung, and liver metastases developed during the early postoperative period, it was hard to attempt any adjuvant chemotherapy in LCNEC. If a diagnosis of LCNEC of the CBD was possible preoperatively, we could consider neoadjuvant multimodal treatments before resection to improve the prognosis [11, 21, 32]. However, it was difficult to diagnose NEC of the CBD preoperatively, because there is no difference between adenocarcinoma and NEC in symptoms, blood tests, and imaging studies. In most cases, the definitive diagnosis was established by histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of the surgical specimen. Only three cases were diagnosed preoperatively by percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy with biopsy [11], ERCP with brushing [14], and endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy [12]. In our case, we were not able to detect malignant cells by brush cytology of the bile duct. The submucosal location of NEC causes a large number of false-negative results on brush biopsy, making it difficult to achieve a correct preoperative diagnosis.

In our case, CA19-9 was elevated to a high level (40,635 U/mL), but it was thought that the abnormal value was caused by chronic cholestasis and cholangitis. The patient’s postoperative values of CA19-9 reduced to a normal level immediately and did not correlate with the cancer recurrence.

Cho et al. suggested that NEC of the CBD should be considered in differential diagnosis of causes of obstructive jaundice and hemobilia [25]. We examined the intraductal ultrasonography of the CBD in our case and detected a large quantity of clots in the lower bile duct. It was thought that this appearance was due to LCNEC, which was often associated with necrosis. The Ki-67 index in the LCNEC component was higher than in the adenocarcinoma component (72 vs. 27%), and probably reflecting this difference, the SUVmax of the LCNEC was high (20.7) on the FDG-PET. When the SUVmax reaches an abnormally high level, it seems reasonable to suspect a different type of carcinoma.

Conclusions

In summary, we report a case of LCNEC of the CBD. This disease is extremely rare and has an aggressive malignant potential, including invasiveness and metastasis. There are no effective treatments, including resection. Accumulation of more cases and further studies of multimodal treatment are required to improve the prognosis of patients with this disease.

Abbreviations

- CA19-9:

-

Carbohydrate antigen 19-9

- CBD:

-

Common bile duct

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ERCP:

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- FDG-PET:

-

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

- LCNEC:

-

Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma

- NET:

-

Neuroendocrine tumor

- SCNEC:

-

Small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma

- SUVmax:

-

Maximum standardized uptake value

References

Klimstra DS, Modlin IR, Coppola D, Lloyd RV, Suster S. The pathologic classification of neuroendocrine tumors: a review of nomenclature, grading, and staging systems. Pancreas. 2010;39:707–12.

Komminoth P, Arnold R, Capella C, Klimstra DS, Kloppel G, Rindi G, et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC Press; 2010. p. 274–6.

Sabanathan S, Hashimi H, Nicholson G, Edwards AS. Primary oat cell carcinoma of the common bile duct. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1988;33:285–6.

van der Wal AC, Van Leeuwen DJ, Walford N. Small cell neuroendocrine (oat cell) tumour of the common bile duct. Histopathology. 1990;16:398–400.

Nishihara K, Tsuneyoshi M, Niiyama H, Ichimiya H. Composite glandular-endocrine cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct: immunohistochemical study. Pathology. 1993;25:90–4.

Yamamoto J, Abe Y, Nishihara K, Katsumoto F, Takeda S, Abe R, et al. Composite glandular-neuroendocrine carcinoma of the hilar bile duct: report of a case. Surg Today. 1998;28:758–62.

Kim SH, Park YN, Yoon DS, Lee SJ, Yu JS, Noh TW. Composite neuroendocrine and adenocarcinoma of the common bile duct associated with Clonorchis sinensis: a case report. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:942–4.

Miyashita T, Konishi K, Noto M, Taniguchi K, Kaji M, Kimura H, et al. A case of small cell carcinoma of the common bile duct. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2001;98:1195–8.

Edakuni G, Sasatomi E, Satoh T, Tokunaga O, Miyazaki K. Composite glandular-endocrine cell carcinoma of the common bile duct. Pathol Int. 2001;51:487–90.

Kuraoka K, Taniyama K, Fujitaka T, Nakatsuka H, Nakayama H, Yasui W. Small cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct: case report and immunohistochemical analysis. Pathol Int. 2003;53:887–91.

Hazama K, Suzuki Y, Takahashi M, Takahashi Y, Yoshioka T, Takano S, et al. Primary small cell carcinoma of the common bile duct, in which surgical treatment was performed after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:870–2.

Arakura N, Hasebe O, Yokosawa S, Imai Y, Furuta S, Hosaka N. A case of small cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct which could be diagnosed before operation. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2003;100:190–4.

Park HW, Seo SH, Jang BK, Hwang JY, Park KS, Cho KB, et al. A case of primary small cell carcinoma in the common bile duct. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2004;43:260–3.

Thomas NE, Burroughs FH, Ali SZ. Small-cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct and concurrent clonorchiasis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;32:92–3.

Kaiho T, Tanaka T, Tsuchiya S, Yanagisawa S, Takeuchi O, Miura M, et al. A case of small cell carcinoma of the common bile duct. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:363–7.

Sato K, Waseda R, Tatsuzawa Y, Fujinaga H, Wakabayashi T, Ueda Y, et al. Composite large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the common bile duct. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:105–7.

Viana Miguel MM, García-Plata Polo E, Vidal Doce O, Aldea Martínez J, de la Plaza Galindo M, Santamaría García JL. Oat cell carcinoma of the common bile duct. Cir Esp. 2006;80:43–5.

Jeon WJ, Chae HB, Park SM, Youn SJ, Choi JW, Kim SH. A case of primary small cell carcinoma arising from the common bile duct. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;48:438–42.

Nakai N, Takenaka H, Hamada S, Kishimoto S. Identical p53 gene mutation in malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour of the scalp and small cell carcinoma of the common bile duct: the necessity for therapeutic caution? Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:482–5.

Arakura N, Muraki T, Komatsu K, Ozaki Y, Hamano H, Tanaka E, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct diagnosed with EUS-FNA and effectively treated with chemoradiation. Intern Med. 2008;47:621–5.

Hosonuma K, Sato K, Honma M, Kashiwabara K, Takahashi H, Takagi H, et al. Small-cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct: a case report and review of the literature. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:129–32.

Okamura Y, Maeda A, Matsunaga K, Kanemoto H, Boku N, Furukawa H, et al. Small-cell carcinoma in the common bile duct treated with multidisciplinary management. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:575–8.

Yamaguchi Y, Shimizu H, Yoneda E. A case of recurrent endocrine cell carcinoma of the common bile duct successfully treated by hepatic artery infusion with CPT-11 and CDDP. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2009;36:823–5.

Demoreuil C, Thirot-Bidault A, Dagher C, Bou-Farah R, Benbrahem C, Lazure T, et al. Poorly differentiated large cell endocrine carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:194–8.

Sung Bum Cho, Sun Young Park, Young-Eun Joo. Small cell carcinoma of extrahepatic bile duct presenting with hemobilia. 한소화기학회지 2009;54:186-90. doi:10.4166/kjg.2009.54.3.186

Sasatomi E, Nalesnik M, Marsh J. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct: case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(28):4616–23.

Ninomiya R, Ozawa F, Mitsui T, Komagome M, Sato S, Akamatsu N, et al. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2013;40(12):1765–7.

Park S, Moon S, Ryu Y, Hong J, Kim Y, Chae G, et al. Primary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma in the common bile duct: first Asian case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(47):18048–52.

Kihara Y, Yokomizo H, Urata T, Nagamine M, Hirata T. A case report of primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the perihilar bile duct. BMC Surg. 2015; 15(125) doi:10.1186/s12893-015-0116-z

Harada K, Sato Y, Ikeda H, Maylee H, Igarasi S, Okumura A, et al. Clinicopathologic study of mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinomas of hepatobiliary organs. Virchows Arch. 2012;460:281–9.

Albores-Saavedra J, Nadji M, Henson DE, Ziegels-Weissman J, Mones JM. Intestinal metaplasia of the gallbladder: a morphologic and immunocytochemical study. Hum Pathol. 1986;17:614–20.

Shimono C, Suwa K, Sato M, Shirai S, Yamada K, Nakamura Y, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the gallbladder: long survival achieved by multimodal treatment. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14:351–5.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Yoshiaki Imamura (Hospital Pathological Department, University of Fukui Hospital) for micrographs and the immunohistochemistry.

Funding

None.

Authors’ contributions

MM drafted the manuscript. MM, DF, and KKo performed the surgery and revised the manuscript. KKa, SK, and YH participated in the surgery. KKa and TG comprehensively supervised this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

When obtaining an informed consent for surgical procedure, a general consent was also obtained from the patient, for publication and presentation, as usual.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Murakami, M., Katayama, K., Kato, S. et al. Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the common bile duct: a case report and a review of literature. surg case rep 2, 141 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-016-0269-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40792-016-0269-8