Abstract

Background

Although neuroendocrine tumors are most commonly found in the digestive system, neuroendocrine tumors originating from the bile duct are rare, and neuroendocrine carcinomas derived from the perihilar bile duct are extremely rare. This report presents the clinical course and clinicopathological features of neuroendocrine carcinomas arising from the extrahepatic bile duct.

Case presentation

A 70-year-old Japanese woman was preoperatively diagnosed with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, and a radical resection with an extended left hepatic lobectomy and a choledochojejunostomy was performed. From the histopathological findings, we diagnosed the tumor as a neuroendocrine carcinoma of the bile duct (small cell type) with lymph node metastasis. The patient was treated with the same adjuvant chemotherapy as that used for small cell carcinoma of the lung. At 10 months after surgery, there was no recurrence of the disease.

Conclusion

Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the extrahepatic biliary tracts is a very rare and highly malignant disease with a poor prognosis. A multidisciplinary approach could improve the prognosis for this neoplasm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification system (2010) defines neoplasms with neuroendocrine differentiation as neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). These are stratified as NET Grade 1 (G1), NET Grade 2 (G2), and neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) [1]. Although NETs are most commonly found in the digestive system, NETs originating from the extrahepatic bile duct are rare, and NECs arising from the perihilar bile duct are extremely rare [2]. In this report, we present the clinical course and clinicopathological features of a case of NEC originating from the extrahepatic bile duct, as well as the results of a literature review on this subject.

Case presentation

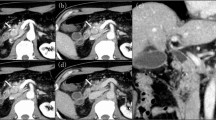

A 70-year-old Japanese woman presented to our hospital for investigation of a chief complaint of jaundice. The patient had no family history of cancer. A physical examination revealed no remarkable findings. Laboratory data showed abnormally elevated levels of total bilirubin (3.6 mg/dL; normal, 0.2-1.0 mg/dL), AST, ALT, and γ-GTP. The serum level of CEA was normal; however, the CA19-9 was above the normal range (47 U/ml; normal, 0–37 U/ml). An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 3 cm enhancing mass located in the hilar bile duct extending to the left hepatic duct (Fig. 1a) and an enlarged regional lymph node along the common bile duct (Fig. 1b). In recent years, for the preoperative biliary drainage in patients with malignant biliary tract obstruction, we prefer endoscopic retrograde drainage rather than percutaneous transhepatic drainage in regard to adverse events, such as vascular injury and cancer dissemination. Therefore, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed, and cholangiography revealed the obstruction of the hilar to upper portion of bile duct (Fig. 2). And endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD) tube was placed. A bile duct brush cytologic specimen obtained at the time of ERCP showed small clusters of relatively small atypical cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and scant cytoplasm. A salt-and-pepper chromatin pattern and cell molding, which are typical in neuroendocrine tumors, were not apparent. The cytologic diagnosis at this point was adenocarcinoma, possibly poorly differentiated. The patient was diagnosed with hilar cholangiocarcinoma with regional lymph node involvement. Abdominal and chest CT scans showed no other neoplastic lesions. A radical resection was performed, including an extended left hepatic lobectomy, excision of the caudate lobe and the extrahepatic bile duct, dissection of the regional lymph nodes, and a choledochojejunostomy.

In the resected specimen, the mucosa of the perihilar bile duct was diffusely rough, and the duct wall was thickened in a 3 cm portion of the proximal common hepatic duct. Microscopically, the thickened bile duct wall was infiltrated by irregular islands and nests of cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and a high nuclear-to- cytoplasmic ratio (Fig. 3a). The tumor cells were relatively small, approximately 2 to 3 times larger than the background lymphocytes (Fig. 3b). Rosette-like structures were not seen. Numerous mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies were present. Immunohistochemical stains showed the tumor cells to be positive for synaptophysin (Fig. 3c) and CD56 (Fig. 3d), and focally positive for chromogranin A. The Ki-67/MIB-1 Labeling Index was 70 % (Fig. 3e). Based on these findings, a pathological diagnosis of small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma was established. Two out of 8 regional lymph nodes were positive for metastatic carcinoma.

Pathological findings. Hematoxylin-eosin stained histologic sections of the resected perihilar bile duct. The tumor cells were arranged in the cellular nests and cords infiltrating the bile duct wall. The mucosa epithelium was mostly eroded (upper right) (a: ×100). The tumor cells were round or oval with scant cytoplasm. Numerous mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies are noted (b: ×400). In the immunohistochemical studies, the tumor cells were diffusely positive for synaptophysin (c: ×400), and CD56 (d: ×400). Approximately 70 % of the tumor cells were positive for Ki-67 (e: ×400)

There were no postoperative complications, and the patient received 4 courses of adjuvant chemotherapy with a regimen of irinotecan (50 mg/m2) and carboplatin (5 AUC/body). Ten months after surgery, there was no recurrence of the disease.

Discussion

NECs were previously classified as small cell carcinomas (SCCs), large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, or poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas [3]. NEC is a poorly differentiated, high-grade, malignant neoplasm composed of small cells or intermediate to large cells. In the digestive system, NECs have been reported in the esophagus, the ampulla of Vater [4], the pancreas [5], and the gallbladder [6]. However, NECs in the bile duct are extremely rare.

We conducted a PubMed systematic literature search (1985–2014) using keywords such as “neuroendocrine carcinoma,” “small cell,” and “biliary tract,” and found only 23 reported cases of NEC of the extrahepatic biliary tracts, excluding the intrahepatic bile duct, the gallbladder, and the ampulla of Vater (Table 1, [7–29]). SCC was the most common histologic subtype of NEC of the extrahepatic bile ducts (19 of 23 cases; Table 1). There were only 3 cases of large cell carcinomas of the common bile duct (cases 21 to 23, Table 1). NEC can occur anywhere in the extrahepatic bile duct, but the middle portion of the common bile duct appears to be the most common site of involvement. The prognosis for NEC of the bile duct appears to be poor. Of the 23 cases with follow-up data, 57 % (12/23) of the patients died 3 to 20 months after surgery, and only 2 patients were reported to have survived more than 2 years. NEC of the biliary system has a high incidence of distant metastasis [15, 16, 19, 20, 22, 24–29]. Consequently, it has a poor prognosis, and surgical resection alone is not an effective treatment. A report by Levenson revealed that there is no survival benefit from using surgery to treat either small cell lung cancer or extrapulmonary SCC [30]. This may be because the most important prognostic factor is the extent of disease at diagnosis, and most patients with extrapulmonary SCC already have occult metastasis [30]. Of the 12 patients died within 20 months after surgery, 9 cases were identified their recurrence pattern and all of them were distant metastases [15, 16, 19, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 29]. Meanwhile, the long survival 2 cases had locoregional lymph node metastases without distant metastasis [13, 27]. Since NEC of the biliary system had a high incidence of distant metastasis, locolegional lymph node metastasis could not be a prognostic factor. In the report of 37 cases of neuroendocrine tumor of ampulla of Vater, the authors did not find any prognostic value of the locoregional lymph node metastases and lymphadenectomy [31].

If there is a biopsy-proven preoperative diagnosis of NEC, then preoperative chemotherapy can improve the prognosis in comparison to surgery alone or surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy. Hazama et al. revealed that neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery resulted in an excellent response for SCC of the common bile duct [15]. Okamura et al. reported that multidisciplinary management, consisting of preoperative chemotherapy, a curative resection, adjuvant chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, may scontribute to a prolonged survival for SCC of the common bile duct [26]. In most cases of NEC of the biliary system diagnosed from pathological findings of resected specimens, surgical resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy is the generally accepted optimal treatment.

Although there is no established standard treatment for extrapulmonary SCC, chemotherapy should be attempted, if possible, because SCC is often chemosensitive [32]. The recommended chemotherapy regimen for extrapulmonary SCC is the same as that for small cell lung cancer. For patients with a diagnosis of the small cell type of NEC who are able to undergo surgical resection, adjuvant chemotherapy consisting of cisplatin and etoposide is also recommended for prevention of systemic recurrence [33, 34].

Conclusion

In summary, neuroendocrine carcinoma of the extrahepatic biliary tracts is a very rare and highly malignantdisease with a poor prognosis. Although treatment strategies have not yet been established, a multidisciplinary approach at diagnosis of NEC of the biliary system, as well as further studies on therapeutic management could improve the prognosis of this highly malignant neoplasm.

Consent

A written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report, along with all corresponding figures. A copy of the consent is available for review by the editors of this journal.

Abbreviations

- CA19-9:

-

carbohydrate antigen 19–9

- CEA:

-

carcinoembryonic antigen

- ERCP:

-

endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- NEC:

-

neuroendocrine carcinoma

- NET:

-

neuroendocrine tumour

- SCC:

-

small cell carcinoma

References

Komminoth P, Arnold R, Capella C, Klimstra DS, Kloppel G, Rindi G, et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010. p. p274–6.

Chamberlain RS, Blumgart LH. Carcinoid tumors of the extrahepatic bile duct. A rare cause of malignant biliary obstruction. Cancer. 1999;86:1959–65.

Rindi G, Arnold R, Bosman FT, Capella C, Klimstra DS, Kloppel G, et al. Nomenclature and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2010. p. 13–4.

Suzuki S, Tanaka S, Hayashi T, Harada N, Suzuki M, Hanyu F, et al. Small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:450–3.

Nakamura Y, Tajiri T, Uchida E, Arima Y, Aimoto T, Katsuno A, et al. Changes to levels of serum neuron-specific enolase in a patient with small-cell carcinoma of the pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:93–8.

Eriguchi N, Aoyagi S, Noritomi T, Imamura M, Sato S, Fujiki K, et al. Adeno-endocrine cell carcinoma of the gallbladder. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:97–101.

Sabanathan S, Hashimi H, Nicholson G, Edwards AS. Primary oat cell carcinoma of the common bile duct. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1988;33:285–6.

Van der Wal AC, Van Leeuwen DJ, Walford N. Small cell neuroendocrine (oat cell) tumour of the common bile duct. Histopathology. 1990;16:398–400.

Nishihara K, Tsuneyoshi M, Niiyama H, Ichimiya H. Composite glandular-endocrine cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct: immunohistochemical study. Pathology. 1993;25:90–4.

Yamamoto J, Abe Y, Nishihara K, Katsumoto F, Takeda S, Abe R, et al. Composite glandular-neuroendocrine carcinoma of the hilar bile duct: report of a case. Surg Today. 1998;28:758–62.

Kim SH, Park YN, Yoon DS, Lee SJ, Yu JS, Noh TW. Composite neuroendocrine and adenocarcinoma of the common bile duct associated with Clonorchis sinensis: a case report. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:942–4.

Miyashita T, Konishi K, Noto M, Taniguchi K, Kaji M, Kimura H, et al. A case of small cell carcinoma of the common bile duct. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2001;98:1195–8.

Edakuni G, Sasatomi E, Satoh T, Tokunaga O, Miyazaki K. Composite glandular-endocrine cell carcinoma of the common bile duct. Pathol Int. 2001;51:487–90.

Kuraoka K, Taniyama K, Fujitaka T, Nakatsuka H, Nakayama H, Yasui W. Small cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct: case report and immunohistochemical analysis. Pathol Int. 2003;53:887–91.

Hazama K, Suzuki Y, Takahashi M, Takahashi Y, Yoshioka T, Takano S, et al. Primary small cell carcinoma of the common bile duct, in which surgical treatment was performed after neoadjuvant chemotherapy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:870–2.

Arakura N, Hasebe O, Yokosawa S, Imai Y, Furuta S, Hosaka N. A case of small cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct which could be diagnosed before operation. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2003;100:190–4.

Park HW, Seo SH, Jang BK, Hwang JY, Park KS, Cho KB, et al. A case of primary small cell carcinoma in the common bile duct. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2004;43:260–3.

Thomas NE, Burroughs FH, Ali SZ. Small-cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct and concurrent clonorchiasis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2005;32:92–3.

Kaiho T, Tanaka T, Tsuchiya S, Yanagisawa S, Takeuchi O, Miura M, et al. A case of small cell carcinoma of the common bile duct. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:363–7.

Sato K, Waseda R, Tatsuzawa Y, Fujinaga H, Wakabayashi T, Ueda Y, et al. Composite large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the common bile duct. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:105–7.

Viana Miguel MM, García-Plata Polo E, Vidal Doce O, Aldea Martínez J, de la Plaza GM, Santamaría García JL. Oat cell carcinoma of the common bile duct. Cir Esp. 2006;80:43–5.

Jeon WJ, Chae HB, Park SM, Youn SJ, Choi JW, Kim SH. A case of primary small cell carcinoma arising from the common bile duct. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;48:438–42.

Nakai N, Takenaka H, Hamada S, Kishimoto S. Identical p53 gene mutation in malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour of the scalp and small cell carcinoma of the common bile duct: the necessity for therapeutic caution? Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:482–5.

Arakura N, Muraki T, Komatsu K, Ozaki Y, Hamano H, Tanaka E, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct diagnosed with EUS-FNA and effectively treated with chemoradiation. Intern Med. 2008;47:621–5.

Hosonuma K, Sato K, Honma M, Kashiwabara K, Takahashi H, Takagi H, et al. Small-cell carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct: a case report and review of the literature. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:129–32.

Okamura Y, Maeda A, Matsunaga K, Kanemoto H, Boku N, Furukawa H, et al. Small-cell carcinoma in the common bile duct treated with multidisciplinary management. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:575–8.

Yamaguchi Y, Shimizu H, Yoneda E. A case of recurrent endocrine cell carcinoma of the common bile duct successfully treated by hepatic artery infusion with CPT-11 and CDDP. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2009;36:823–5.

Demoreuil C, Thirot-Bidault A, Dagher C, Bou-Farah R, Benbrahem C, Lazure T, et al. Poorly differentiated large cell endocrine carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:194–8.

Sasatomi E, Nalesnik MA, Marsh JW. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct: Case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(28):4616–23.

Levenson RM, Ihde DC, Matthews MJ, Cohen MH, Gazdar AF, Bunn PA, et al. Small cell carcinoma presenting as an extrapulmonary neoplasm: sites of origin and response to chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981;67:607–12.

Dumitrascu T, Dima S, Herlea V, Tomulescu V, Ionescu M, Popescu I. Neuroendocrine tumours of the ampulla of Vater: clinico-pathological features, surgical approach and assessment of prognosis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397(6):933–43.

Kim JH, Lee SH, Park J, Kim HY, Lee SI, Nam EM, et al. Extrapulmonary small-cell carcinoma: a single-institution experience. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:250–4.

Hogan BA, Thornton FJ, Brannigan M, Browne TJ, Pender S, O’Kelly P, et al. Hepatic metastases from an unknown primary neoplasm (UPN): survival, prognostic indicators and value of extensive investigations. Clin Radiol. 2002;57:1073–7.

Quoix E, Breton JL, Daniel C, Jacoulet P, Debieuvre D, Paillot N, et al. Etoposide phosphate with carboplatin in the treatment of elderly patients with small-cell lung cancer: a phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:957–62.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge all the medical and surgical staff that took care of the patient. All authors report no source of funding for conducting this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YK performed the surgery, wrote the case report, made literature review and drafted the manuscript. HY is the senior surgeon who performed all operations assisted by the authors, and revised the manuscript. TU is the gastroenterologist and performed preoperative examination. MN is the pathologist, performed conventional and immunohistochemical staining of NEC of extrahepatic biliary tract, and revised the manuscript. TH is the chief of our division of general surgery, and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kihara, Y., Yokomizo, H., Urata, T. et al. A case report of primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the perihilar bile duct. BMC Surg 15, 125 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-015-0116-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-015-0116-z