Abstract

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), an international committee of experts, has recently published its updated report on diagnosis and management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Compared to the previous version, this documents has been an extensively revised: the definition has been simplified, highlighting the importance of respiratory symptoms, and disease development is further discussed, including new insights on lung development. Spirometry is still required for the diagnosis, and it is described as fundamental tool for evaluating prognosis, disease progression, and non-pharmacologic treatment. However, differently from the previous version, spirometry is no longer included in the ABCD tool (ie, a practical tool proposed to assess COPD symptom burden and guide pharmacologic treatment), which is now centered exclusively on respiratory symptoms and history of exacerbation. Subsequently, pharmacologic treatment has been shifted towards a more personalized approach, reflecting the ongoing process toward a comprehensive, patient-tailored management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) is an international committee of experts who periodically update the knowledge on the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), based on an extensive scientific discussion and published evidence in the literature [1].

Since 2001 the document has been published every year reporting recommendations to be shared and implemented in different countries. Every 5-year the document is extensively revised so representing a formal new update by GOLD committee on the disease.

Review

This year 2017, the GOLD initiative published the 5-year update on the diagnosis and management of COPD. This document encloses new insights on the disease, specifically on diagnosis, classification and therapeutic approaches, which represent substantial changes from previous publications (Table 1).

Disease definition

The definition of COPD now reads as “a common, preventable and treatable disease that is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases”. Compared to the previous definition, it introduces the concept of persistent symptoms, while discarding the putative pathogenic mechanism (i.e., enhanced inflammatory response); exacerbation, progression, and comorbidities are similarly not included in the revised definition of the disease. Overall, the new definition is essentially a description of lung and airways abnormalities following exposure to noxious stimuli and leading to symptoms.

The addition of a clear reference to persistent respiratory symptoms is the first novelty of this report, and focuses on the patient and on the clinical presentation. In this regard, the correct interpretation of chronic symptoms has always been a much debated topic: for example, chronic dyspnea, cough, and sputum production have been reported in smokers who do not have documented airflow obstruction [2]. These symptomatic smokers exhibit higher rates of respiratory exacerbations, lower exercise capacity, worse quality of life, and often receive bronchodilators, even without a confirmed diagnosis of COPD [3, 4]. Moreover, these subjects may have slightly altered lung function (e.g., lower lung function, greater airway thickening or emphysema), compared to smokers without symptoms [4, 5]. Thus, the GOLD 2017 recognizes that chronic respiratory symptoms may be present in the absence of abnormal spirometry, may be associated with structural lung alteration, and may precede the development of airflow limitation [6]. However, available data are insufficient to perform a radical change in the definition of COPD, to include these subjects and align them to individuals with documented airflow obstruction. Moreover, albeit recognizing the limits of spirometry, this test is central in the detection of airflow limitation, and thus remains the cornerstone of the diagnosis of COPD, as in the previous documents [6].

Disease development

The section on factors that influence disease development and progression has been largely updated, discussing the origin of COPD, relating it to interactions with host factors and environmental exposures. Cigarette smoking remains the most well studied risk factor for the so-called self-inflicted disease in the 2017 document.

However, not all smokers will develop COPD, while airflow limitation may develop in non-smokers [6], thus the putative pathogenic mechanisms have been investigated further. For example, poor lung growth is listed among the important risk factors for COPD, as any element that affects lung growth during gestation and childhood. It seems that prenatal and early-life insults (e.g., maternal smoking during pregnancy, and lung infection in early childhood) may influence the correct development of the organs, including the lungs, and their capacity for repair [7, 8]. Therefore, lung function has different trajectories of development and different trajectories of decline during the entire lifespan [9].

Exposure to particles such as occupational exposures, indoor air pollution from biomass cooking and heating in poorly ventilated dwellings, low socioeconomic status, and lung disorders (eg, airway hyper-responsiveness, chronic bronchitis, infections) are other cited environmental risk factors for the development and the progression of COPD [6].

The final pathogenic mechanism still recognizes an altered chronic inflammatory response in the lung, which induces parenchymal tissue destruction, altered lung repair, and abnormal defense mechanisms, ultimately resulting in emphysema and small airway fibrosis [10, 11]. Moreover, systemic inflammation may be present, and could play a role in the development of multiple comorbid conditions. The mechanisms for this amplified inflammatory response are not completely understood, as disease development and progression derives from complex and lifelong interactions between genetic background, genes expression, environmental exposures, and risk factors.

Diagnosis and assessment

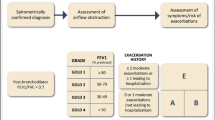

The chapter on diagnosis of COPD presents a major change, i.e., the revision of the ABCD assessment tool. In the new document, the tool has been modified to utilize respiratory symptoms and exacerbations to assign categories (ABCD), but separating the spirometric measure from these evaluations. This change is another example of the ongoing process toward a patient-tailored management. At first, COPD was classified into four grades (mild, moderate, severe and very severe) according to post-bronchodilator FEV1: lung function drove allocation of pharmacologic therapy to prevent and control symptoms and exacerbations [12]. Later, in 2011, the assessment by categories was introduced: this tool evaluated symptoms, history of exacerbations, and the severity of airflow limitation. Patients were thus split into four categories (ie, ABCD), according to their symptoms, lung impairment and future risk of exacerbations. The pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic therapies matched this assessment [13]. However, the staging system in COPD remained a matter of debate, and subsequent analysis did not prove either scheme to be able of predicting mortality at the individual level. Moreover, the GOLD 2011 re-classification shifted the overall COPD severity distribution to more severe categories, but without clearly documented benefits on outcomes [14].

Furthermore, the ABCD classification based on airflow severity and patient-reported outcome caused some confusion: for example, group C (high risk without significant symptoms) was rather uncommon, and had similar exacerbation frequency than group B (high symptoms but low risk); on the other hand, group D (which included subjects with severe airflow limitation alone, or with history of frequent exacerbations alone, or with both risk factors) had significant heterogeneity in exacerbation rate [15, 16].

Therefore, in the current update, the ABCD categories are derived exclusively from symptoms and history of exacerbations. The separation of airflow obstruction from clinical parameters was made to clarify what was being evaluated and ranked by severity. Moreover, this scheme was proposed to facilitate treatment recommendations based on individual parameters. Various recommendations, especially pharmacologic treatments, are based on ABCD categories, and thus derived exclusively from patient’s symptom experiences and exacerbation history. The revised assessment acknowledges, on the one hand, the additional and important prognostic information derived both from dyspnea and exacerbation and, on the other, the limitations of FEV1 in guiding the choice of therapy [17,18,19]. Indeed, significant heterogeneity in symptoms and quality of life has been reported in patients with similar degree of airflow obstruction, and daily or weekly variation in dyspnea was not related to FEV1 [20]. As the primary goal of medications in COPD is to reduce symptoms, frequency and severity of exacerbations, and improve health status, it seems clear why a clinical assessment tool has been suggested.

Therefore, few therapeutic decisions are now based on spirometry, such as considering an alternative diagnosis when symptoms are disproportionate to the degree of airflow obstruction, or evaluating additional non-pharmacological and interventional procedures [1].

Notwithstanding, FEV1 is an important prognostic marker, and it has been significantly linked to negative outcomes such as higher mortality [21, 22], and increased risk of lung cancer [23]. Similarly, the rate of FEV1 decline during follow-up may be an important and clinically relevant indicator of the rate and type of disease progression [24, 25].

Furthermore, the ABCD assessment tool has various limitations: this tool has been proposed to structure and standardize the assessment of symptom burden and to create treatment plans in COPD patients [6], but has limited value in predicting mortality: for example, the 2011-ABCD GOLD predicted global mortality with an area under the curve of ROC of 0.68 in one report [26], and 0.52 in another one [27]. Moreover, symptom assessment is based either on the mMRC or the CAT questionnaire, but these two tests are not equivalent, may even be discordant in the same patient and, thus, are not interchangeable [28]. Further, data have been provided to support the philosophy beyond the new 2017 ABCD assessment tool, but obviously there is no evidence yet on its real efficacy in guiding therapeutic decision. Consequently, data on this new approach to COPD are eagerly awaited.

Disease management

The chapter on management presents some important updates in the present document: for example, the evaluation of the inhaler technique is now recommended. This recommendation acknowledges the evidence suggesting that the inhalation technique of the COPD patient may not be always appropriate, nor the compliance with treatment be optimal [29]. According to recent data on inhaler technique errors, it seems that only 6% of the patients have an optimal skill and adherence with inhalers [30]. Thus, it is necessary that clinicians recognize the different devices and techniques, and suggest the most appropriate for each individual patient [31].

Additionally, the patient with COPD is asked to play an active role in the whole management of the disease, through self-management, participation in rehabilitation programs, and discussion over end of life and prolonged care (i.e., hospice). For example, published evidence suggests that physical activity is decreased in COPD patients, leading to a downward spiral of inactivity, linked to reduced health status, and increased rates of hospitalization and mortality [32]. On the contrary, COPD subjects who perform some level of regular physical activity have a significantly lower risk of mortality [33]. Thus, self-management interventions move beyond the sole education of the patient, and usually include smoking cessation, self-recognition of exacerbations, coping with breathlessness, and advice on physical activity, diet and medications. As a consequence, dyspnea, quality of life and clinical outcomes (e.g., admissions) may improve, although data are not fully consistent, due to substantial heterogeneity among interventions and study populations [34,35,36].

Based on the previously discussed revisions on COPD patients’ classification, the 2017 document presents important updates in the therapeutic indications and the pharmacological treatment algorithms.

Overall, it is most recommended that drugs should be personalized, according to the individual’s characteristics: symptoms and future risk of exacerbations, but not FEV1, are clinical key elements that guide the pharmacological management in stable COPD.

Moreover, and for the first time, the new algorithms of treatment include strategies for escalation and de-escalation of therapies based on symptoms and exacerbations. In particular, increasing symptoms and/or exacerbation number may warrant additional medications, i.e., combined bronchodilators (LABA and LAMA) or ICS to reduce future risks. Published evidence evaluating the effects of ICS withdrawal (de-escalation) is not consistent, although the outcome differences between patients continuing medication and patients who do not are not significant [37]. A trial on over 2000 patients with severe COPD receiving triple therapy demonstrated that ICS withdrawal was non-inferior to continued use of glucocorticoid, with respect to exacerbations, dyspnea and health status, although a significant reduction in FEV1 (−38 ml) was observed [38]. A post-hoc analysis of the same study population suggested that patients with higher exacerbation rate had higher eosinophil counts: authors concluded that eosinophil counts ≥ 4% (or 300 cell/μL) may identify a subgroup of severe COPD at higher exacerbation risk following withdrawal [39]. Therefore, blood eosinophil level might identify those patients with distinct characteristics (e.g., older, associated asthma, higher readmission rates) and different response to ICS [11, 40, 41].

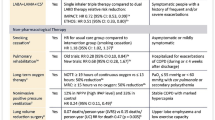

Overall, the role and indication of ICS in COPD patients is revised in the new document. Group B patients should be started on single bronchodilator, either LAMA or LABA, while the LAMA/LABA combination may be started soon in the more symptomatic patients. Accordingly, a recent exploratory analysis, showed that the LAMA/LABA combination was superior to placebo and monotherapy in symptomatic patients with low exacerbation risk [42]. ICS in not recommended alone nor as an addition to either LAMA or LABA in group B.

Group C patients should be prescribed a LAMA as the initial therapy (ICS/LABA combination or LAMA were the first choice in 2011 document). If exacerbations persist, combination therapy is then indicated, preferably LABA/LAMA as inhaled corticosteroids may increase the risk of pneumonia [43, 44].

Similarly, patients in group D should be started on LAMA or LAMA/LABA according to the revised document. The main source for these new indication was the FLAME trial [45]: this was a large, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, non-inferiority trial, where 3362 symptomatic COPD patients with a history of exacerbations were randomized to LAMA/LABA (indacaterol–glycopyrronium) or ICS/LABA (salmeterol–fluticasone). The primary outcome was the annual rate of exacerbations, which was significantly lower in the group of patients treated with LAMA/LABA than with ICS/LABA. Further, the LAMA/LABA group had a longer time to first exacerbation, and a lower annual rate of moderate/severe exacerbations. The overall incidence of adverse events was similar, although the incidence of pneumonia was significantly higher in the ICS/LABA group. Thus, ICS performs as an anti-inflammatory agent in the COPD population, and in the 2017 GOLD document it is indicated in combination with LABA in those patients with moderate to very severe COPD and repeated exacerbations, or showing poor response to bronchodilators [1].

Notwithstanding, as published evidence is conflicting, the scientific debate on the definitive role of ICS in patients with stable COPD is still open. Recently, a large, real-life, prospective, randomized trial, the SALFORD study, has been conducted in 75 general practitioners in UK to evaluate usual clinical practice in the management of this disease: 2802 COPD patients with a history of exacerbations, and taking regular maintenance inhaler therapy, were randomized to either ICS/LABA (fluticasone furoate–vilanterol) or continuation of usual care as determined by the general practitioner. The primary outcome was the mean annual rate of moderate or severe exacerbations, and exacerbation rate was 8.4% lower with ICS/LABA, with no difference in the time to first exacerbation, nor in the rate of severe exacerbations and serious adverse events, including pneumonia [46]. Likewise, an earlier observational study evaluating the real-life practice in Italy, has documented a benefit on survival when adding ICS to LABA in patients experiencing exacerbations: more specifically, 18,615 patients discharged for an acute exacerbation of COPD were identified from hospital records, and classified as new users of LABA alone or new users of ICS and LABA. Crude mortality rate was higher in the LABA alone group, and also the adjusted hazard ratio favored combination therapy [47]. Additionally, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of LABA (vilanterol) versus ICS/LABA (fluticasone furoate-vilanterol) in 1620 COPD patients with a history of exacerbation and current COPD symptoms, reported a statistically significant adjusted mean treatment difference in FEV1 from baseline, in favor of the ICS/LABA combination therapy [48].

Moving to non-pharmacologic treatments, for the first time the GOLD document introduces intervention bronchoscopy with valves or coils as an option in selected patients with emphysema and hyperinflation. Diverse factors need to be considered when choosing bronchoscopic lung reduction versus surgical resection (lung volume reduction surgery), including the extent and pattern of emphysema identified on HRCT, the presence of interlobar collateral ventilation, patient and provider preferences and local expertise. For example, in patients with fissure integrity or lack of interlobar collateral ventilation based on physiologic assessment, endobronchial valve or lung coil treatment may be evaluated [49]. Similarly, patients with homogenous emphysema may be considered for bronchoscopic lung reduction [50]. On the contrary, endobronchial valve therapy is not useful in patients with lack of fissure integrity or if interlobar collateral ventilation is present. Overall, it seems that these procedures can improve clinical health outcomes, although with a non-negligible rate of adverse events [51].

Comorbidities

Finally, the 2017 GOLD document devotes new insights to comorbidities in its last chapter. COPD is known to be associated with other concomitant conditions, including cardiovascular and muscular-skeletal diseases, osteoporosis, mood disorders, and cancer, evoking multimorbidity as the most likely clinical figure in these patients [52]. Accordingly, the importance of the active search, diagnosis, and treatment of any comorbidity associated to COPD is now recommended [1]. Interestingly, the last section of this chapter focuses on the issue of multiple drug therapies, indicating that treatments should be kept simple, avoiding the unbearable polypharmacy that these patients are often exposed to. Pharmacological treatments should be revised taking into account evidence of likely benefits and harms for the individual patient, as well as outcomes important to the person.

Conclusions

The GOLD 2017 document reports several new insights into the diagnosis and the management of the patients with COPD. This seems a step toward achieving a comprehensive, personalized and patient-centered approach, which will probably be the key for treating the complex patient with COPD.

Abbreviations

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- FEV1 :

-

Forced expiratory volume in the 1st second

- GOLD:

-

Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease

- HRTC:

-

High resolution computed tomography

- ICS:

-

Inhaled corticosteroids

- LABA:

-

Long-acting beta agonists

- LAMA:

-

Long-acting muscarinic antagonists

References

Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report: GOLD Executive Summary. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(3).

Martinez CH, Kim V, Chen Y, Kazerooni EA, Murray S, Criner GJ, et al. The clinical impact of non-obstructive chronic bronchitis in current and former smokers. Respir Med. 2014;108(3):491–9.

Tan WC, Bourbeau J, Hernandez P, Chapman KR, Cowie R, FitzGerald JM, et al. Exacerbation-like respiratory symptoms in individuals without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from a population-based study. Thorax. 2014;69(8):709–17.

Woodruff PG, Barr RG, Bleecker E, Christenson SA, Couper D, Curtis JL, et al. Clinical significance of symptoms in smokers with preserved pulmonary function. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(19):1811–21.

Regan EA, Lynch DA, Curran-Everett D, Curtis JL, Austin JHM, Grenier PA, et al. Clinical and radiologic disease in smokers with normal spirometry. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1539–49.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org. (Accessed Apr 2017).

Thomsen M, Nordestgaard BG, Vestbo J, Lange P. Characteristics and outcomes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in never smokers in Denmark: a prospective population study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(7):543–50.

Martinez FD. Early-life origins of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):871–8.

Carraro S, Scheltema N, Bont L, Baraldi E. Early-life origins of chronic respiratory diseases: understanding and promoting healthy ageing. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1682–96.

Lange P, Celli B, Agustí A, Boje Jensen G, Divo M, Faner R, et al. Lung-function trajectories leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):111–22.

Barnes PJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(1):16–27.

Hogg JC. Pathophysiology of airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2004;364(9435):709–21.

Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(6):532–55.

Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(4):347–65.

Soriano JB, Lamprecht B, Ramírez AS, Martinez-Camblor P, Kaiser B, Alfageme I, et al. Mortality prediction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease comparing the GOLD 2007 and 2011 staging systems: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(6):443–50.

Jones PW, Nadeau G, Small M, Adamek L. Characteristics of a COPD population categorised using the GOLD framework by health status and exacerbations. Respir Med. 2014;108(1):129–35.

Han MK, Muellerova H, Curran-Everett D, Dransfield M, Washko G, Regan EA, et al. Implications of the GOLD 2011 disease severity classification in the COPDGene cohort. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(1):43–50.

Lange P, Marott JL, Vestbo J, Olsen KR, Ingebrigtsen TS, Dahl M, et al. Prediction of the clinical course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, using the new GOLD classification: a study of the general population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(10):975–81.

Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Locantore N, Müllerova H, Tal-Singer R, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1128–38.

Nishimura K, Izumi T, Tsukino M, Oga T. Dyspnea is a better predictor of 5-year survival than airway obstruction in patients with COPD. Chest. 2002;121(5):1434–40.

Kessler R, Partridge MR, Miravitlles M, Cazzola M, Vogelmeier C, Leynaud D, et al. Symptom variability in patients with severe COPD: a pan-European cross-sectional study. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(2):264–72.

Almagro P, Martinez-Camblor P, Soriano JB, Marin JM, Alfageme I, Casanova C, et al. Finding the Best Thresholds of FEV1 and Dyspnea to Predict 5-Year Survival in COPD Patients: The COCOMICS Study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e89866.

Celli BR, Cote CG, Lareau SC, Meek PM. Predictors of Survival in COPD: more than just the FEV1. Respir Med. 2008;102 Suppl 1:S27–35.

Fry JS, Hamling JS, Lee PN. Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence relating FEV1 decline to lung cancer risk. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:498.

Kim J, Yoon HI, Oh Y-M, Lim SY, Lee J-H, Kim T-H, et al. Lung function decline rates according to GOLD group in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1819–27.

de Torres JP, Casanova C, Marín JM, Pinto-Plata V, Divo M, Zulueta JJ, et al. Prognostic evaluation of COPD patients: GOLD 2011 versus BODE and the COPD comorbidity index COTE. Thorax. 2014;69(9):799–804.

Ansari K, Keaney N, Kay A, Price M, Munby J, Billett A, et al. Body mass index, airflow obstruction and dyspnea and body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea scores, age and pack years-predictive properties of new multidimensional prognostic indices of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary care. Ann Thorac Med. 2016;11(4):261–8.

Mittal R, Chhabra SK. GOLD classification of COPD: discordance in criteria for symptoms and exacerbation risk assessment. COPD. 2017;14(1):1–6.

Van der Palen J, Thomas M, Chrystyn H, Sharma RK, van der Valk PD, Goosens M, et al. A randomised open-label cross-over study of inhaler errors, preference and time to achieve correct inhaler use in patients with COPD or asthma: comparison of ELLIPTA with other inhaler devices. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2016;26:16079.

Sulaiman I, Cushen B, Greene G, Seheult J, Seow D, Rawat F, et al. Objective Assessment of Adherence to Inhalers by COPD Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016. doi:10.1164/rccm.201604-0733OC.

Laube BL, Janssens HM, de Jongh FHC, Devadason SG, Dhand R, Diot P, et al. What the pulmonary specialist should know about the new inhalation therapies. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(6):1308–31.

Watz H, Pitta F, Rochester CL, Garcia-Aymerich J, ZuWallack R, Troosters T, et al. An official european respiratory society statement on physical activity in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(6):1521–37.

Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Benet M, Schnohr P, Antó JM. Regular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort study. Thorax. 2006;61(9):772–8.

Bird S, Noronha M, Sinnott H. An integrated care facilitation model improves quality of life and reduces use of hospital resources by patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic heart failure. Aust J Prim Health. 2010;16(4):326–33.

Jonkman NH, Schuurmans MJ, Groenwold RHH, Hoes AW, Trappenburg JCA. Identifying components of self-management interventions that improve health-related quality of life in chronically ill patients: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(7):1087–98.

Hillebregt CF, Vlonk AJ, Bruijnzeels MA, van Schayck OC, Chavannes NH. Barriers and facilitators influencing self-management among COPD patients: a mixed methods exploration in primary and affiliated specialist care. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:123–33.

Nadeem NJ, Taylor SJC, Eldridge SM. Withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids in individuals with COPD--a systematic review and comment on trial methodology. Respir Res. 2011;12:107.

Magnussen H, Disse B, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Kirsten A, Watz H, Tetzlaff K, et al. Withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(14):1285–94.

Watz H, Tetzlaff K, Wouters EFM, Kirsten A, Magnussen H, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Blood eosinophil count and exacerbations in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids: a post-hoc analysis of the WISDOM trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(5):390–8.

Couillard S, Larivée P, Courteau J, Vanasse A. Eosinophils in COPD exacerbations are associated with increased readmissions. Chest. 2017;151(2):366–73.

DiSantostefano RL, Hinds D, Le HV, Barnes NC. Relationship between blood eosinophils and clinical characteristics in a cross-sectional study of a US population-based COPD cohort. Respir Med. 2016;112:88–96.

Singh D, Maleki-Yazdi MR, Tombs L, Iqbal A, Fahy WA, Naya I. Prevention of clinically important deteriorations in COPD with umeclidinium/vilanterol. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:1413–24.

Yang IA, Clarke MS, Sim EH, Fong KM. Inhaled corticosteroids for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2012;(7):CD002991.

Crim C, Dransfield MT, Bourbeau J, Jones PW, Hanania NA, Mahler DA, et al. Pneumonia risk with inhaled fluticasone furoate and vilanterol compared with vilanterol alone in patients with COPD. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(1):27–34.

Wedzicha JA, Banerji D, Chapman KR, Vestbo J, Roche N, Ayers RT, et al. Indacaterol-Glycopyrronium versus Salmeterol-Fluticasone for COPD. N Engl J Med. 2016;347:2222–34.

Vestbo J, Leather D, Diar Bakerly N, New J, Gibson JM, McCorkindale S, et al. Effectiveness of fluticasone furoate-vilanterol for COPD in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(13):1253–60.

Di Martino M, Agabiti N, Cascini S, Kirchmayer U, Bauleo L, Fusco D, et al. The effect on total mortality of adding inhaled corticosteroids to long-acting bronchodilators for COPD: a real practice analysis in italy. COPD. 2016;13(3):293–302.

Siler TM, Nagai A, Scott-Wilson CA, Midwinter DA, Crim C. A randomised, phase III trial of once-daily fluticasone furoate/vilanterol 100/25 μg versus once-daily vilanterol 25 μg to evaluate the contribution on lung function of fluticasone furoate in the combination in patients with COPD. Respir Med. 2017;123:8–17.

Zoumot Z, Davey C, Jordan S, McNulty WH, Carr DH, Hind MD, et al. Endobronchial valves for patients with heterogeneous emphysema and without interlobar collateral ventilation: open label treatment following the BeLieVeR-HIFi study. Thorax. 2017;72(3):277–9.

Valipour A, Slebos D-J, Herth F, Darwiche K, Wagner M, Ficker JH, et al. Endobronchial valve therapy in patients with homogeneous emphysema. Results from the IMPACT study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(9):1073–82.

Van Agteren JE, Hnin K, Grosser D, Carson KV, Smith BJ. Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction procedures for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;23(2):CD012158.

Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management. NICE Guidance and guidelines. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng56. (Accessed May 2017).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This review article was not funded by any third party.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

SR provided the content of the body text and literature search. EC and LB equally contributed to revision. EC was responsible for the final editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Authors consent the publication of the present manuscript in its present forma and agree with this.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Roversi, S., Corbetta, L. & Clini, E. GOLD 2017 recommendations for COPD patients: toward a more personalized approach. COPD Res Pract 3, 5 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40749-017-0024-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40749-017-0024-y