Abstract

Background

The ultimate goal of preventing intestinal parasites among pregnant women is to reduce maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality. Numerous primary studies were conducted in East Africa presented intestinal parasite infection and associated factors among pregnant women. However, the pooled finding is not known. Therefore, this review aimed to identify the pooled prevalence of intestinal parasite infection and its determinants among pregnant women in East Africa.

Methods

Articles published from 2009 to 2021 were searched in PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, and HINARI databases. The search for unpublished studies such as thesis and dissertations was checked in Addis Ababa University and Africa Digital Library. PRISMA checklist was used to report the review. Articles published in the English Language were considered. The data were extracted by two authors using data extraction checklists on Microsoft excel. Heterogeneity among the included studies was checked using I2 statistics on forest plots. Sensitivity and sub-group analyses were conducted to assess the presence of primary studies, and study characteristics responsible for the observed heterogeneity.

Results

Of the 43 identified articles, about 23 articles were removed due to duplications. Then, by assessing the abstracts and full texts, four articles were removed because they failed to meet the eligibility criteria. Finally, 16 articles were included in the systematic and meta-analysis.The pooled prevalence of intestinal parasites among pregnant women in East Africa was 38.54 (28.77, 48.32). In this study, variables like residing in rural areas (OR: 3.75; CI: 1.15,12.16), availability of latrine(OR: 2.94; 95% CI: 2.22, 3.91), eating raw fruits/vegetables (OR: 2.44; 95% CI: 1.16, 5.11). and sources of water as unprotected sources (OR: 2.20; 95% CI: 1.11,4.35) show statistically significant association with the increased burden of intestinal parasites among pregnant women.

Conclusion

The burden of intestinal parasite infection among pregnant women in East Africa was high. Therefore, efforts should be made in deworming pregnant women at the community and institutional level by stakeholders to reduce the burden of intestinal parasite infections and related complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Intestinal parasitic infections are mainly Soil-transmitted helminths which is a group of parasitic diseases caused by nematode worms that are transmitted to humans by fecal contaminated soil. The soil-transmitted helminths of major concern to humans are Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura, Necator americanus, and Ancylostoma duodenale [1]. Globally, about 24% of the world’s population is infected with soil-transmitted helminth infections, and sub-Saharan Africa areas are highly affected by the infection [2].

Studies showed that there is a high prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in pregnant women, especially in some low- and middle-income countries[3]. Lack of proper sanitation and hygiene, the habit of eating raw vegetables, walking barefoot, and water sources are the major identified factors associated with soil-transmitted helminthic infections [4]. Pregnancy drains the body physically, physiologically, and immunologically, and together with intestinal parasitic infection, it may lead to fatal outcomes. Intestinal parasitic infections in pregnancy have been associated with serious adverse outcomes such as anemia, low birth weight, and mother and fetus morbidity and mortality [5,6,7,8].

World Health Organization urged endemic countries to start seriously tackling worms, specifically schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths. It recommends periodic medicinal deworming without a previous individual diagnosis to all at-risk people, such as adolescents and pregnant and lactating women living in endemic areas, to achieve the 2030 global target of eliminating soil-transmitted helminths [2]. However, recent studies conducted in different parts of East Africa showed that the prevalence and impacts of these parasites are high among pregnant women [9,10,11].

Despite these deleterious effects on pregnant women, fetuses, and newborns in East Africa, the pooled prevalence, and associated risk factors of intestinal parasitic infections among pregnant women are not well explained. Numerous primary studies were conducted to assess the burden of intestinal parasites among pregnant women across East African countries. However, the pooled prevalence and factors associated with intestinal parasite is not identified. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess the pooled prevalence of intestinal parasite infection and associated factors among pregnant women in East Africa.

Methods

Search strategies

Both published and unpublished articles were extensively searched for databases that include PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, HINARI, and Google Scholar.The search for unpublished studies such as thesis and dissertations was checked in Addis Ababa University and Africa Digital Library. The literature search was for the articles published from 2009 to 2021. Searches were conducted using terms such as “ Prevalence”, “Magnitude”, “Intestinal parasite”, “Intestinal helminths”, “Soil-transmitted helminths”, “Parasitic infection”, Pregnant women”, “associated factors”, “determinants” and all lists of East African countries “ by using Boolean operators like “ AND”and “OR”. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist and flow diagram were used for reporting the procedure.

Selection and eligibility criteria

This systematic review and meta-analysis included studies that were conducted on intestinal parasite infection and associated factors among pregnant women in East Africa. The contents of each article were independently reviewed by two investigators (GM & DB) and finally articles that fulfilled the following criteria were included in the study. The study populations were all pregnant women living in East Africa. The review included all observational study designs reporting intestinal parasite infection among pregnant women in East Africa. Articles reported in the English language were included. We excluded articles that were not fully accessible, after at least two email contact attempts with the primary authors.

Outcome measurement

This review considered two main outcomes. Intestinal parasite infection among pregnant women was the primary outcome of this study. It is measured as the total number of intestinal parasite infection cases over a total number of all women multiplied by 100. The second outcome of this study was to identify factors associated with intestinal parasites among pregnant women. For the second outcome, we determined the association between intestinal parasites and associated factors in the form of the log odds ratio. Residence (urban versus rural), availability of latrine (absence versus presence), the habit of eating raw fruit/vegetables (eating versus not eating), educational status (no education/primary education versus secondary and above), barefooted (Yes versus no), source of drinking water (protected versus unprotected), a habit of eating soil (absence versus presence) and hand washing after toilet (absence versus presence) were factors including as the determinants of intestinal parasite infection.

Data extraction and quality assessment

In this review, the quality of the included studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies [12]. Reference management software (Endnote version X7.2) was used to combine search results from databases and to remove duplications. Studies were screened using abstracts and titles. Then, the eligibility of the studies was evaluated using predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The data were extracted by two authors (GM and DB) using data extraction checklists on Microsoft excel. For the outcome, intestinal parasite infections and associated factors, data were extracted in a format of two by two tables and then the log odd ratio was calculated based on the findings of the primary studies. The checklist for data extraction contains the author's name, year of publication, country, study design, sample size, response rate, and the number of participants with the outcome. Disagreement between two independent reviewers was resolved by involving the third reviewer (GK).

Statistical analysis

After data extraction from original articles, data were exported to STATA version 14 for analysis. Heterogeneity among the included studies was checked using the Cochran Q test (chi-squared statistic) and I2 statistic on forest plots Sensitivity and sub-group analyses were conducted out to assess the presence of primary studies and study characteristics responsible for the observed heterogeneity.Heterogeneity was observed for the first outcome; therefore, a random-effects model was used to determine the pooled prevalence of intestinal parasite infection. A funnel plot, Egger’s tests were computed to test the presence of publication bias.

Results

Study selection

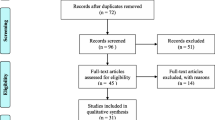

A total of forty-three articles were identified through database and library catalog search. Of the identified articles, about 23 articles were removed due to duplications. Then, by assessing the abstracts and full texts, four articles were removed because they failed to meet the eligibility criteria. Finally, 16 articles that scored seven and above on the JBI quality appraisal were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram were used to present the systematic review process (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 4881 study partcipantswere involved in this systematic review. All included studies were cross-sectional. The sample size ranges from a minimum of 153 which was conducted in Kenya [13] to a maximum of 980 which was conducted in Rwanda [14]. Of the included studies, twelve of them were conducted in Ethiopia, two conducted in Kenya, one conducted in Uganda, and one conducted in Rwanda (Table 1).

Pooled prevalence of intestinal parasite among pregnant women

In this review, the highest prevalence of intestinal parasites was observed among pregnant women in Kenya (76.15 (71.92, 80.38), while the lowest 10.98 (7.69, 14.28) in Uganda. In this study, high heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 98.8 and P-value < 0.001), and therefore random effect model was used to assess the pooled prevalence of intestinal parasites among pregnant women in East Africa. Accordingly, the pooled prevalence of intestinal parasites among pregnant women in East Africa was 38.54 (28.77, 48.32) (Fig. 2).

Sub-group analysis and publication bias

In this meta-analysis, subgroup analysis was conducted using the country. The subgroup analysis showed that the prevalence of intestinal parasites among pregnant women was 40.15(30.95, 49.36) in Ethiopia [4, 6, 9, 11, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22], 44.96(-16.21, 106.14) in Kenya [13, 23], 34.29(31.31, 37.26) in Rwanda [14], and 10.98(7.69, 14.28) in Uganda [24] (Fig. 3). To assess the presence of publication bias, the funnel plot, and Egger test at 5% significant level were computed. The statistical test of the egger’s test indicated that there is no publication bias (P = 0.449). However, the visual interpretation of the funnel plot figure looks asymmetrical (Fig. 4).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to identify the single study influence on the overall meta-analysis using a random effect model. The result showed that there was no strong evidence for the effect of single study influences on the overall meta-analysis (Fig. 5).

Factors related with intestinal parasite among pregnant women

Association between residence and intestinal parasite

To assess the association between the intestinal parasite infection and residence, six articles [4, 9, 15,16,17, 19] were included. According to the finding, the rural residence was positively associated with the presence of the intestinal parasite. The pooled effect of the meta-analysis showed the positive association between rural residence and intestinal parasites among pregnant women.

The pooled finding indicated that the odds of developing intestinal parasite infection were 3.75 times higher among women who reside in the rural than their counterparts (OR: 3.75; CI: 1.15, 12.16). The random model effect model was used as heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 96.7, P = < 0.001) (Fig. 6).

Association between the availability of latrine and Intestinal parasite

Four articles [9, 15,16,17] were included to assess the association between availability latrine and intestine parasite. Three articles showed the association between latrine and intestinal parasites [9, 15, 16] and one article did not show the association [17]. The study result indicated that the absence of latrine was associated with intestinal parasite among pregnant women. The pooled effect of the meta-analysis showed that the absence of latrine is positively associated with intestinal parasite infection. Pregnant women who have no latrine were 2.94 times more likely to have intestinal parasite compared to women who have latrine (OR: 2.94; 95% CI: 2.22, 3.91). A Fixed model was used since heterogeneity was not exhibited (I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.413) (Fig. 7).

Association between a habit of eating raw fruit/vegetables and intestinal parasite

Six articles were included in the analysis to estimate the pooled effect of a habit of eating raw fruit/vegetables on the intestinal parasite among pregnant women [9, 11, 15,16,17, 19]. The overall pooled estimate of a habit of eating raw fruit/vegetables revealed that there is an association between eating raw fruit/ vegetables and intestinal parasites (OR: 2.44; 95% CI: 1.16, 5.11). The pooled result revealed that intestinal parasite infection was 2.44 times higher among women who have a habit of eating raw fruits/vegetables compared to their counterparts. The random-effect model was used since heterogeneity was exhibited (I2 = 92.3%, P = < 0.001) (Fig. 8).

Association between educational status and intestinal parasite among pregnant women

Six articles were involved in the analysis to estimate the pooled effect of educational status and intestinal parasites among pregnant women [4, 9, 11, 16, 17, 24]. The overall pooled estimate of educational status revealed that there is no association between educational status and intestinal parasite (OR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.50, 2.22). The random-effect model was used since heterogeneity was exhibited (I2 = 90.7%, P = < 0.001) (Fig. 9).

Association between barefooted and intestinal parasite among pregnant women

Five articles were included to assess the pooled effect of barefooted and intestinal parasites among pregnant women [4, 9, 15, 20, 22]. From these, only one article showed a positive association between barefooted and intestinal parasite infection among pregnant women [4]. The pooled estimate effect revealed that there is no association between barefooted and intestinal parasites among pregnant women (OR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.14, 1.94). The random-effect model was used since heterogeneity was exhibited (I2 = 96.7%, P = < 0.001) (Fig. 10).

Association between a habit of eating soil and intestinal parasite among pregnant women

Four articles were included to assess the association between the habit of eating soil and intestinal parasite among pregnant women [16, 17, 19, 20] in which only one article showed a significant association between the habit of eating soil and intestinal parasite [19]. However, the pooled estimate effect revealed that there is no association between eating soil and intestinal parasite among pregnant women (OR: 1.59; 95% CI: 0.98, 2.59). The random-effect model was used for this finding (I2 = 60.1%, P = < 0.057) (Fig. 11).

Association between the source of water and intestinal parasite among pregnant women

Regarding the source of water, five articles, four from Ethiopia [4, 16, 17, 22] and one from Uganda [24] were included in the analysis. From these, two articles showed a significant association between the source of drinking water and intestinal parasite infection [4, 24] The pooled effect model showed a significant association between the source of water and intestinal parasite among pregnant women (OR: 2.20;95% CI: 1.11,4.35). The pooled result indicated that intestinal parasite infection was 2.20 times higher among women who drink unprotected water compared to their counterparts (Fig. 12). In this finding, random-effect model was used (I2 = 75.3%, P-value = 0.003).

Association between Hand washing after toilet and intestinal parasite among pregnant women

To assess the association between handwashing after toilet and intestinal parasite infection, three articles were included [16, 17, 22] in which all of them didn’t show the association between handwashing after facility and intestinal parasite infection among pregnant women. The pooled effect model showed no significant association between handwashing after toilet and intestinal parasite infection among pregnant women OR: 1.29(95% CI: 0.77, 2.18) (Fig. 13). The fixed-effect model was used since no heterogeneity was exhibited (I2 = 17.5, P = 0.297).

Discussion

The ultimate goal of preventing intestinal parasites among pregnant women is to reduce maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality. Consequently, effective preventive intervention and implementation approaches can be implemented if the burden and determinant factors are well identified. Thus, this systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the pooled prevalence and determinant factors of intestinal parasites among pregnant women in East Africa.

The pooled prevalence of intestinal parasites among pregnant women in this systematic review and meta-analysis was 38.54 (28.77, 48.32). This is similar to findings of the studies conducted in India (42.67%) [25], Ghana (30.5%) [26], Ibadan Nigeria (43.4%) [27], Colombia (41%) [28], Southeast Nigeria (32.4%) [29], Tribhuvan University teaching hospital, Nepal (35%) [8], Ram Janaki Hospital, Janakpurdham, Nepal (42%) [30], and Cameroon (47.1%) [31]. The pooled prevalence in this study is lower than studies conducted in the Caribbean (66.2%) [32], Venezuela (73.9%) [33], Thai Burmese border, Southeast Asia (70%) [34], Guinea (81%) [35], Sub-Saharan Africa (66%) [36] and Indonesia (67.7%) [37]. The low prevalence in this review might be due to improvement in awareness creation for the community by health extension workers (in the case of East Africa) and working closely with the community on the risk of intestinal parasites and its prevention methods.

However, the pooled prevalence in this study is higher than studies conducted in Kasoa polyclinic, Ghana (14.3%) [38], Abeokuta, Nigeria (21.8%) [39], Benin (2.2%) [40], Enugu State, Nigeria (16.3%) [41], Osun State, Nigeria (12%) [42], and Edo State, Nigeria (18.2%) [43]. The discrepancy might be a result of the difference in access to health facilities and the socio-demographic characteristics of the study populations.

In this study, variables like residing in rural areas, availability of latrine, eating raw fruits/vegetables, and sources of water as unprotected sources show statistically significant associations with the burden of intestinal parasites among pregnant women. However, having the habit of eating soil, educational status, hand washing after toilet, and being barefooted had no statistical association with the burden of intestinal parasites among pregnant women.

The pooled effect of this systematic review and meta-analysis showed a positive association between rural residence and intestinal parasites among pregnant women. Pregnant women who come from rural areas were 3.75 times more likely to have intestinal parasites compared to women from Urban. This is consistent with studies conducted in a tertiary multispecialty teaching hospital in Mumbai, India [25] and a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted on the global prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and associated risk factors in pregnant women [7]. This may be because, pregnant women who reside in rural areas are uneducated, less knowledgeable about the risk and preventive mechanisms of intestinal parasites, practice poor personal hygiene, use contaminated water, and mostly walk barefoot. All this can predispose them to intestinal parasites.

The pooled effect of the meta-analysis showed that the absence of latrine is positively associated with intestinal parasites. Pregnant women who have no latrine were 2.94 times more likely to have intestinal parasites compared to women who have a latrine. This is in line with studies conducted in a tertiary multispecialty teaching hospital in Mumbai, India [25], Kasoa Polyclinic, Ghana, in which pregnant women who shared a toilet facility had 2.78-fold greater odds of intestinal parasite infections compared to those who owned a toilet facility [38], and Abeokuta, Nigeria [39]. This may be because, in the absence of latrine, there is open defecation, which can contaminate food and water that pregnant women consume, and finally, predispose them to intestinal parasites.

In this review, the pooled estimate effect revealed that there is an association between eating raw fruits/vegetables and intestinal parasite infection among pregnant women. This finding is supported by a study conducted in India in which eating raw fruits/vegetables is a risk factor for intestinal parasites during pregnancy [25]. This is because eating raw fruits and vegetables is closely associated with helminthic diseases due to the high probability of the presence of infective parasitic ova in fruits/vegetables, which can predispose pregnant women to infection with intestinal parasites.

The pooled effect model of this systemic review and meta-analysis showed a significant association between the source of water and intestinal parasites among pregnant women. Pregnant women who use unprotected water sources were 2.2 times more likely to have intestinal parasites compared to women who use protected water sources. This is in line with the studies conducted in India [25], Ghana [26], and Southeast Nigeria [29]. This can be justified that unprotected water sources are prone to contamination with different wastes and pathogenic organisms like cysts of protozoon species and eggs of worms which are commonly transmitted to pregnant women by drinking contaminated water. However, in this review, the pooled estimate effect indicated that there is no statistical association between eating soil, educational status, being barefooted, and hand washing after the toilet.

Strength and limitation of the study

Various databases and digital libraries were extensively searched for both published and unpublished articles. However, this review is not without limitations; as primary studies included in this review were cross-sectional in design; it is difficult to conclude the temporal relationship between the intestinal parasite infection and its determinants. Besides, this review included only articles published in the English language; articles published in another language might be excluded.

Conclusion

The current systematic review and meta-analysis findings indicated that more than one-third of pregnant women in East Africa had intestinal parasite infection. This indicates that the burden of intestinal parasite infection among this group was high. Residing in rural, the absence of latrine, having the habit of eating raw fruits/vegetables, and using unprotected sources of drink water were the identified factors associated with Intestinal parasite infection among pregnant women. Therefore, efforts should be made in deworming pregnant women at the community and institutional level by stakeholders to reduce the burden of intestinal parasite infections and related complications.

Availability of data and materials

The data used for this study are presented within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- IPI:

-

Intestinal Parasite Infection

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Organization WH. Soil-transmitted helminthiases: eliminating as public health problem soil-transmitted helminthiases in children: progress report 2001–2010 and strategic plan 2011–2020: World Health Organization; 2012.

Organization WH. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: key facts: World Health Organization;. 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/soil-transmitted-helminth-infections.

Taghipour A, Ghodsian S, Jabbari M, Olfatifar M, Abdoli A, Ghaffarifar F. Global prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and associated risk factors in pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2021;115(5):457–70.

Tesfaye DJ. Prevalence of intestinal helminthiases and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic of Nigist Eleni Mohammed memorial hospital, Hossana, Southern Ethiopia. Open Access Libr J. 2015;2(07):1.

Tsoka-Gwegweni JM, Ntombela N. A double load to carry: parasites and pregnancy. South Afr J Infect Dis. 2014;29(2):52–5.

Bolka A, Gebremedhin S. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection and its association with anemia among pregnant women in Wondo Genet district, Southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):1–8.

Taghipour A, Ghodsian S, Jabbari M, Olfatifar M, Abdoli A, Ghaffarifar F. Global prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and associated risk factors in pregnant women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2020.

Sapkota L, Maharjan M. Anaemia Association with Intestinal Parasitic Infection in Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinic at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital. J Adv Coll Eng Manage. 2017;3:41–7.

Feleke BE, Jember TH. Prevalence of helminthic infections and determinant factors among pregnant women in Mecha district, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):1–6.

Yesuf DA, Abdissa LT, Gerbi EA, Tola EK. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at public health facilities in Lalo Kile district, Oromia Western Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):1–6.

Wachamo D, Bonja F, Tadege B, Hussen S. Magnitude of parasitic infections and associated factors among pregnant women at health facilities in Hawassa, Southern Ethiopia. F1000Res. 2021;10(122):122.

JBI. Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross Sectional Studies: Jounna Briggs Institute; 2017.

Wekesa A, Mulambalah C, Muleke C, Odhiambo R. Intestinal helminth infections in pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at Kitale district hospital, Kenya. Journal of parasitology research. 2014;2014.

Ivan E, Crowther NJ, Mutimura E, Osuwat LO, Janssen S, Grobusch MP. Helminthic infections rates and malaria in HIV-infected pregnant women on anti-retroviral therapy in Rwanda. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(8):e2380.

Misikir SW, Wobie M, Tariku MK, Bante SA. Prevalence of hookworm infection and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at governmental health centers in DEMBECHA district, north West Ethiopia, 2017. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–8.

Mengist HM, Zewdie O, Belew A. Intestinal helminthic infection and anemia among pregnant women attending ante-natal care (ANC) in East Wollega, Oromia. Ethiopia BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):1–9.

Derso A, Nibret E, Munshea A. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care center at Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):1–7.

Getachew M, Tafess K, Zeynudin A, Yewhalaw D. Prevalence Soil Transmitted Helminthiasis and malaria co-infection among pregnant women and risk factors in Gilgel Gibe dam Area Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6(1):1–7.

Hailu T, Abera B, Mulu W, Kassa S, Genanew A, Amor A. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Intestinal Parasitic Infections among Pregnant Women in West Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia. Journal of Parasitology Research. 2020;2020.

Gebrehiwet MG, Medhaniye AA, Alema HB. Prevalence and associated factors of soil transmitted helminthes among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Maytsebri primary hospital North Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):1–6.

Tefera G. Determinants of anemia in pregnant women with emphasis on intestinal helminthic infection at Sher-Ethiopia Hospital, Ziway Southern Ethiopia. Immunol Infect Dis. 2014;2(4):33–9.

Shiferaw MB, Zegeye AM, Mengistu AD. Helminth infections and practice of prevention and control measures among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Anbesame health center Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):1–5.

Van Eijk AM, Lindblade KA, Odhiambo F, Peterson E, Rosen DH, Karanja D, et al. Geohelminth infections among pregnant women in rural western Kenya; a cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3(1):e370.

Apili F, Ochaya S, Osingada CP, Mbalinda SN, Mukunya D, Ndeezi G, et al. Hookworm Infection among Pregnant Women at First Antenatal Visit in Lira, Uganda: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2020;2020.

Supriya Paranjpe NR, Koticha Avani, Nataraj Gita, Mehta Preeti. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in pregnant women. Indian Journal of Microbiology Research. 2020;7(4): .

Ahenkorah B, Nsiah K, Baffoe P, Ofosu W, Gyasi C, Owiredu E-W. Parasitic infections among pregnant women at first antenatal care visit in northern Ghana: A study of prevalence and associated factors. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(7):e0236514.

Alli JAOI, Kolade AF, Nwanze JC, Dada VK, Ogundele M. Prevalence of intestinal nematode infection among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at the University College Hospital, Ibadan Nigeria. Adv Appl Sci Res. 2011;2(4):1–13.

Aranzales AFE, Radon K, Froeschl G, Rondón ÁMP, Delius M. Prevalence and risk factors for intestinal parasitic infections in pregnant women residing in three districts of Bogotá Colombia. BMC public health. 2018;18(1):1–15.

Dimejesi IB, Umeora OU, Egwuatu VE. Prevalence and pattern of soil-transmitted helminthiasis among pregnant women in a tertiary health facility, Southeast Nigeria. Afr J Med Health Sci. 2014;13(1):56.

Yadav K, Prakash S, Yadav BK. Characterization of Intestinal Parasitosis in Pregant Women at Ram Janaki Hospital Janakpurdham Tribhuvan University. J Microbiol. 2020;7:91–103.

Ndamukong K, Asoba G, Achidi E. Intestinal helminth infections among pregnant cameroonian women. East Afr Med J. 2011;88(11):377–83.

Guo F, Forde MS, Werre SR, Krecek RC, Zhu G. Seroprevalence of five parasitic pathogens in pregnant women in ten Caribbean countries. Parasitol Res. 2017;116(1):347–58.

Rodríguez-Morales AJ, Barbella RA, Case C, Arria M, Ravelo M, Perez H, et al. Intestinal parasitic infections among pregnant women in Venezuela. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;2006.

Boel M, Carrara VI, Rijken M, Proux S, Nacher M, Pimanpanarak M, et al. Complex interactions between soil-transmitted helminths and malaria in pregnant women on the Thai-Burmese border. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(11):e887.

Phuanukoonnon S, Michael A, Kirarock WS, Pomat WS, van den Biggelaar AH. Intestinal parasitic infections and anaemia among pregnant women in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. P N G Med J. 2013;56(3/4):119–25.

Adegnika AA, Agnandji ST, Chai SK, Ramharter M, Breitling L, Kendjo E, et al. Increased prevalence of intestinal helminth infection during pregnancy in a Sub-Saharan African community. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;119(23):712–6.

Nurdiati DS, Sumarni S, Hakimi M, Winkvist A. Impact of intestinal helminth infection on anemia and iron status during pregnancy: a community based study in Indonesia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001;32(1):14–22.

Abaka-Yawson A, Sosu SQ, Kwadzokpui PK, Afari S, Adusei S, Arko-Mensah J. Prevalence and Determinants of Intestinal Parasitic Infections among Pregnant Women Receiving Antenatal Care in Kasoa Polyclinic, Ghana. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2020;2020.

Salawu MM, Salawu AH, Ogunfunmilayo TA, Nwadike VU, Adebayo AS. Predictors of soil-transmitted helminthic infection among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at the Federal Medical Center, Abeokuta, Nigeria. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;37(1):27–32.

Akinbo FO, Okonye E, Ande ABA. Intestinal nematodes infection among pregnant women in Benin City. Nig J Exp Clin Biosci. 2015;3(2):65.

Obiezue NR, Okoye IC, Ivoke N, Okorie JN. Gastrointestinal helminth infection in pregnancy: disease incidence and hematological alterations. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(5):497.

Ojurongbe O, Okorie PN, Opatokun RL, Ojurongbe TA, Mabayoje VO, Olowe OA, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of Plasmodium falciparum and soil transmitted helminth infections among pregnant women in Osun state Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2018;18(3):542–51.

Akinbo FO, Olowookere TA, Okaka CE, Oriakhi MO. Co-infection of malaria and intestinal parasites among pregnant women in Edo State, Nigeria. J Med Tropics. 2017;19(1):43.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all authors of the primary studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Funding

No funding is received to undertake this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GM conceptualized the topic of the study and participated in searching for articles. DB and BW searched and extracted articles. GM, GK, TA and MA analyzed the data. DC, AO, ET, GT and RT participated in data extraction, analysis, and write-up of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mosisa, G., Diriba, D., Tsegaye, R. et al. Burden of intestinal parasitic infections and associated factors among pregnant women in East Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. matern health, neonatol and perinatol 9, 5 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-023-00150-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40748-023-00150-8