Abstract

Background

Numerous studies have been carried out on assessing the prevalence of intestinal parasites infections (IPIs) amongpreschool and school-age children in Ethiopia, but there is lack of study systematically gathered and analyzedinformation for policymakers. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to provide a summary on prevalence, geographical distribution and trends of IPIs among preschool and school-age childrenin Ethiopia.

Methods

The search were carried out in Medline via PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct, Web of Science, and Google Scholar from 1996to July2019 for studies describing prevalence of IPIs among preschooland school-age children. We conducted meta-regression to understand the trends and the source of heterogeneity and pooled the prevalence using ‘metaprop’ command using STATA software version 14.

Results

Eighty-three(83) studies examining 56,786 fecal specimens were included. The prevalence of IPIs was 48%(95%CI: 42 to 53%) and showedsignificantly decreasing trends 17% (95% CI: 2.5 to 32%) for each consecutive 6 years) and was similar in males and females. The pooled prevalence in years 1997–2002, 2003–2008, 2009–2014 and > 2014 was 71% (95% CI: 57 to 86%), 42% (95% CI: 27 to 56%), 48% (95% CI: 40 to 56%) and 42% (95% CI: 34 to 49%), respectively. Poly-parasitism was observed in 16% (95% CI: 13 to 19%,) of the cases.

Conclusion

Intestinal parasite infections are highly prevalent among preschool and school-age children and well distributed across the regional states of Ethiopia. Southern and Amhara regional states carry the highest burden. We observed significant decreasing trends in prevalence of IPIs among preschool and school-ageEthiopian children over the last two decades. Therefore, this study is important to locate the geographical distribution and identified high risk areas that should be prioritized further interventions, which complement global efforts towards elimination of IPIs infections by 2020.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Parasitic infections caused by intestinal helminths and protozoan are among the most prevalent infections in developing countries carrying high burden of morbidity and mortality in these areas [1]. Specifically, economically disadvantaged children living in tropical and sub-tropical regionswith a limited or no access to safe drinking water, inadequate sanitation, and substandard housing are the most affected ones [2]. Epidemiological evidence suggests that an estimated over one billion people in the world, majorly children were infected with intestinal parasites caused by helminths and protozoa [3]. Majority of the infections were due to Ascaris lumbricoides, hookworm, and Trichuris trichiura [4, 5]. More than 267 million preschool-age children and 568 million school-age children live in areas where these parasites are intensively transmitted [6]. Cryptosporidium species, Entamoeba histolytica and Giardia duodenalis were the most common protozoan infections in children under 5 years in sub-Saharan Africa [7].

The regional distribution and prevalence differences of IPIs among children are mainly due to differences in degree of fecal contamination of water and food, climatic, environmental and socio-culture [8,9,10]. The prevalence among under-five, preschool and school children were reported as 17.7% in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia [11], 52.8% in an urban slum of Karachi, Pakistan [12], 19.6% in Zambia [13] and 30% in Khartoum, Sudan [13]. In Ethiopia, prevalence varies across the regions in the country. For instance, the prevalence was 85.1% in Wondo Genet (Southern region) [14], 48.1% in Aynalem village (Tigray region) [15], 17.4% in Debre Birhan (Amhara region) [16], 26.6% in Hawassa (Southern region) [17], 24.3% in Wonji Shoa Sugar Estate (Oromia region) [18], 18.7% in Woreta (Amhara region) [19], 25.6% in Dembiya (Amhara region) [20] and 41.1% in Jimma town (Oromia region) [21].

School-agechildren are the most affected ones due to their habits of playing or handling of infested soils, eating with soiled hands, unhygienic toilet practices, drinking and eating of contaminated water and food [22]. Intestinal parasite infections lead to malnutrition, mal-absorption, anemia, intestinal obstruction, mental and physical growth retardation, diarrhea, impaired work capacity, and reduced growth rate constituting important health and social problems [10, 18, 23, 24].

Numerous epidemiological studies have been performed on assessing the prevalence of IPIs among children in Ethiopia, but there is lack of systematically gathered and analyzed information for policymakers. Therefore, the aim of this systematic and meta-analysis was to provide a summary on prevalence, geographical distribution and trends of IPIs among preschool and school-age children in Ethiopia.

Methods

Search strategy and data extraction

The search were carried out in Medline via PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct, Web of Science and Google Scholar using searching terms intestinal parasite infection” OR “helminths” OR “protozoa” AND “Ethiopia”. Searching was carried out on articles published from 1997 to March,2019 and limited human studieswith language restriction to English. A manual search for additional relevant studies using references from retrieved articles and related systematic reviews was also performed to identify original articles we might have missed. Conference abstracts and unpublished studies were excluded. We did our analyses according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [25].

Participants, inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two authors independently (LCH&DE) assessed the inclusion criteria and disagreement was solved by discussion with the third author (ZM). We included the studies if they met the following criteria: the study design was an observational study (prospective cohort, case-control, retrospective cohort, or cross-sectional) or controlled clinical trial which documented the baseline prevalence or incidence of IPIs. We included all studies reported the rateor proportion of IPIs in preschool and/or school-age children or both. We excluded studies reporting case reports, case series, studies that compared the sensitivity and specificity of different methods used for diagnosis of intestinal parasites and studies not reported either prevalence or incidence of IPIs as outcome of interest. The terms preschool and school-age children were defined according to the original studies. Accordingly, preschool-age children were defined aschildren of age below 5 years while,school-agechildren were children of age 5 and above. Poly-parasitism was defined as concurrent infection with different species of intestinal parasites either helminths or protozoa.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The two authors (LCH and DE) defined protocol for data extraction and assessed them independently for eligibility and disagreements were resolved by discussion with the third author (ZM). We extracted information on name of the first author and year of publication, study design, population studied (preschool age children, school age children or both), gender, region & sites of study, Method (s) for identification of the parasites, total sample size and the number of the positives (percentage). The Grading of Recommendation Assessment, development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used to assess the overall quality of evidence [26]. Accordingly, studies were given one point each if theyhad probability sampling, larger sample sizes of more than 200, and repeated detection and up to four points could be assignedto each study. Publications with a total score of 3–4 points were considered as high quality, whereas 2 points represented moderate quality and scores of 0–1 represented low quality.

Statistical analysis

We used forest plots to estimate pooled effect size and effect of each study with their confidence interval (CI) to provide a visual summary of the data. A random-effects model was used in this meta-analysis because of anticipated heterogeneity. All reported P values were 2-sided and were statistical significant if P < 0.05. Statistical heterogeneity among studies was expressed as the P value (Cochran’s Q statistic), where a P < 0.05 and I2 ≤ of 25–50% were considered as low heterogeneity and I2 > 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity. We also used Begg’s Funnel plot and Egger’s regression test for evaluating the possibility of publication bias. A potential source of heterogeneity was investigated by subgroup andmeta-regression analysis. The factors included were geographical regions and cities of Ethiopia, age of children (preschool vs. school-age children), and years of publication (1997–2002, 2003–2008, 2009–2014 and > 2014). We conducted meta-analysis using ‘metaprop’ commandusing STATA software, version 14, STATA Corp,College Station, TX.

Results

Literature searches and selection

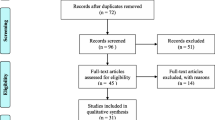

We identified systematically 1198 publications, of which 83 were eligible for inclusion in the final analyses. The details of our search strategy were depicted in Fig. 1. Our initial search of electronic databases such as Medline via PubMed, Scopus, Science direct, Web of Sciences and Google scholar yielded 1195 articles and 3 articles manually from which 186 records remained after removing 1012 duplications. Up on screening the articles, 99 articles were further excluded; 90 were irrelevant because they were not specifically about preschool or school-age children, 6 studies were about sensitivity and specify of diagnosis of IPIs, 3 articles were review articles. Up on further access to the full texts of 87 articles, 4 were excluded for the following reasons; 2 were meta-analyses and 2 articles lacked outcome of interest. Finally, 83 published between 1997 and 2019 fulfilling the inclusion criteria were included in the analyses.

The sample size of the included studies ranged from 100 [27] to 15,455 [28] with a total number of 56,786 participants [14, 16, 17, 21, 24, 27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103]. Most of the studies were reported from Amhara regional 33(40%) followed by Oromia region 21(25%). The rests were reported from South region 18(22%), Tigray region 9(11%), Benishangul-Gumuz region 1(1%) and Addis Ababa city 1(1%). With regard to the study design, majority of the studies were cross sectional in design (79 studies), 2 were controlled clinical trials, 2 were prospective follow up cohort studies and 1 was case-control. Sixty six studies were about IPIs in school-age children, 13 were in preschool-age children (under-five) and 4 were studies involved both preschool and school-age children. According to our quality assessment criteria, 34 publications were of high quality with a score of 3, 12 had a score of 2 indicating moderate quality and the remaining 37 were of low quality with a score of zero or one [Table 1]. Prevalence estimate and heterogeneity analysis.

A total of 27,354 of the 56,786 children examined during the period under review were infected with one or more species of intestinal parasites yielding an overall prevalence of (n = 27,354) 48%(95%CI: 42 to 53%) with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 99.50%, regression coefficient: -0.23, 95% CI: − 0.38 to − 0.09, p = 0.002, Fig. 2). A range of parasites were detected in the studies including Ascaris lumbricoides, Hookworm, Trichuris trichuria, Strongyloides stercoralis, Enterobius vermicularis, Schistosoma mansoni, Hymenolepsis nana, Taenia species, Giardia lamblia/intestinalis/duodenalis, Entamoeba histolytica/dispar and Cryptosporidium species. Subgroup analysis showed that the prevalence of IPIs was 56% (95%CI: 39 to 73%) in Southern region, 51%(95%CI: 43 to 58%) in Amhara region, 40% (95%CI: 31 to 50%) in Oromia region, and 41%(95%CI: 28 to 54%) in Tigray region as shown in Figs. 3 and 4. The age related prevalence was 52% (95%CI: 46 to 58%,) in school-age children and 30% (95%CI: 18 to 34%) preschool-age children (p = 0.002) as shown in Fig. 5.

The pooled prevalence of IPIs in year 1997–2002, 2003–2008, 2009–2014 and > 2014 was 71% (95% CI: 57 to 86%), 42% (95% CI: 27 to 56%), 48% (95% CI: 40 to 56%) and 42% (95% CI: 34 to 49%), respectively [Fig. 6]. We did meta-regression analyses to search for the sources of heterogeneity. We detected no significance difference in geographical distribution (regression coefficient: 0.025, 95% CI: − 0.11 to 0. 06, p = 0.56) as shown Fig. 7a.The results of the analyses showed that age (regression coefficient: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.15 to 0.60, p = 0.002, Fig. 7b) and year of publication (regression coefficient: -0.17, 95% CI: − 0.32 to − 0.025, p = 0.023, Fig. 7c) might be sources of heterogeneity,

Prevalence of IPIs by area of residence, gender and poly-parasitism status

Thirteen studies (N = 12,356) reported the proportion of IPIs based on residence area. The pooled prevalence of overall IPI was not significantly differ between rural and urban areas; rural 22 95% CI: 10 to 30%, Additional file 1) and urban 23% (95% CI: 14 to 32%, Additional file 2). Forty two studies (N = 36,218) had separate data on the prevalence of IPIs for males and females. The pooled prevalence formales was 24% (95%: CI 20 to 28%, Additional file 3) while, it was 22% (95% CI: 18 to 25%, Additional file 4) for females. Poly-parasitism was observed in 16% (95% CI: 13 to 19%, Additional file 5) of children and 36% (95% CI: 30 to 41%, Additional file 6) of children were infected with a single species of parasite.

Discussion

The pooled prevalence of IPIs in preschool and school-age Ethiopian children was 48%(95%CI: 42 to 53%). The prevalence is higher in Southern (56%) and Amhara regions (51%).We observed a significant decrease in the prevalence of IPIs among children in Ethiopia over the last two decades (22 years). The burden of infection was higher among school-age children compared to preschool-age children (52% vs.30%, p = 0.002), however, it was similar in males and females as well as in urban and rural inhabitants. Poly-parasitism was observed in 16% of preschool and school-age children while, single infection was documented in 36% of the children participated in the study.

The overall pooled prevalence estimate (48%) observed in the present systematic review and meta-analysis is similar to the study from Nigeria (54.8%) [106], Rwanda (50.5%) [107], Afghanistan(47.6%) [108],Syria (42.5%) [109] and in Palestine (40.5%) [110]. However, the finding of this systematic review and meta-analysis is higher than that of Cameron(24.1%) [111], Rwanda (25.4%) [112], Iran (38%) [113], Turkey(31.7–37.2%) [114] and Egypt (26.5%) [115]. The difference might be attributed to socio-economic status, poor hygiene and sanitary facilities, weather, climate and environmental factors. For example, a study in Ethiopia showed that Ascaris lumbricoidesinfections were more common in children living in households with lower incomes (prevalence ratio = 6.68, 95% CI = 1.01–44.34) and that Giardia lamblia infections were more common in children living in households that used an unprotected water source (prevalence ratio = 1.95, 95% CI = 0.96–3.99) [32]. In addition, most Ethiopian communities have the habit of consuming uncooked meat, which mightincrease the risk of exposure to human helminths. Many of Ethiopian population where the studies conducted involved in irrigation activities for the cultivation of vegetables during the dry season. This irrigation canals create media for the reproduction of vector snails, which might be the cause of the appearance of endemicity of Trematodes infections in the area. It might also be attributed to the specificity and sensitivity of the diagnostic methods employed by the individual studies.

The meta-regression of prevalence of IPIs over time showedsignificant decreasing trends in each 6-years block by 17% (95% CI: 2.5 to 32%) and this declined prevalence was probably due to socioeconomic development, improvement in sanitation and large-scale deworming programs. Many studies from around the world have reported a significant decreasing trend in the prevalence of overall IPIs in recent years,such as the global burden of disease study [5], study from Burkina Faso [116], Nepal [117], Brazil [118] and other from 43 Sub-Saharan [119]. Despite many initiatives and efforts to introduce mass deworming program and improvement in water quality and sanitation, IPIs are still prevalentand the decrease in trend is less than that of other countries (Ethiopia 42% in 2016–2019 vs. Nepal 20. 4% in 211–2015 and Brazil 23.8% in 2010–2011). This might be possibly due to insufficient financial supports in implementation of the strategies that have been known to reduce the infection such as access to safe water supply, personal hygiene and sanitation, deworming and public health awareness.. In addition, lack of political commitment, social and environmental factors might also contribute for the higher prevalence of IPIs in the country. Inadequate community involvement and ownership of control activities are also another possible reason.

The prevalence of IPIs in school-age children was (52%), which was significantly higher than in preschool-age children (30%). This is similar to the study by Jayarani 2014 [120] and Workneh 2014 [121], but opposite to the study by Daryani 2017 [113]. School children carry the heaviest burden of the intestinal parasite associated morbidity due to their habits of playing or handling of contaminated soils, eating with soiled hands, unhygienic toilet practices, drinking and eating of contaminated water and food [22] compared to preschool-age children who usually cared by families. The current control efforts in Ethiopia usually target school-age children, but a significant proportion of preschool-agechildren (30% in this study) were also infected and can be source for the re-infection of treated school-age children. Therefore, it worthy revising the national control program based on regional and national prevalence which included preschool children and other population at risk.

In the present study, the prevalence of IPIs in females (22%) was similar to males (24%), which is similar to the study by Gelaw 2013 [45], but in contrast to study by Daryani 2017 [113] in Iran. In Iran, report indicated that more females have (30.9%) have IPIs than males (16.5%). The difference might be due to cultural and behavioral difference between the two countries.

The distribution of IPIs in this study was relatively similar in both urban and rural areas. This might be due to absence of proper human waste disposal systems, the shortage of safe water supply, the social and poor environmental or personal hygiene in many unplanned urban areas in Ethiopia in addition to similarity of eating habit and life style of both urban and rural areas of the country. So far, reports from Africa and South Asia countries are conflicting. Some were reported higher infection rates of IPIs in rural areas compared to urban areas [122,123,124,125,126] and others reported higher rate of infections in urban children [127]. In fact, comparable data on IPIs in urban and rural settings are very limited. For instance, only 13 studies out of 83 studies included in this meta-analysis were reported prevalence of IPIs in both urban and rural areas and therefore, indicating more work to be done in the future to resolve this issue.

We estimated the geographical distribution and identified high risk areas that should be prioritized control interventions, which complement global efforts towards elimination of IPIs infections by 2020. In addition, this work also highlighted the need for survey in areas where data are not available such as Somalia region, Afar region, Harari, Dire Dawa city and Gambella region or scarce (Addis Ababa city and Benishangul-Gumuz region). The essence of current systematic review and meta- analysis of IPIs data analysis among preschool and school-age children in Ethiopian were to support the efforts undertaken to control and eliminate neglected tropical diseasesby nurturing or supplementing useful national epidemiological data. We hope that the findings of current study provide valuable information to the policymakers, National Health Bureau and other concerned bodies about national and regional distribution and their prevalence in Ethiopia preschool and school-children.

There are a few limitations of the present meta-analysis, which may affect the results. First of all, the review protocol is not registered which could be source of bias.. It is prudent to interpret the results of this study as 37(44.6%) of the included studies were low quality based on our quality assessment criteria. In all of studies included in this review, single stool sample examination were used despite multiple stool samples recommendation for standard diagnosis and therefore, possible underestimation of the prevalence. There is also substantial heterogeneity observed between the studies that affect the interpretation of the results. However, we did meta-regression analyses on various sources including geographical distribution, age category and year of publication. These might comefrom age category (P = 0.002) and year of publication (P = 0.023) but not from geographic distribution (p = 0.56).

Conclusion

Intestinal parasite infections are highly prevalent and well distributed across the regional states of Ethiopia. Southern and Amhara regional states carry the highest burden. Although school-age children have higher prevalence of IPIs compared to preschool-age children, the prevalence is still unacceptably higher among preschool-age children. We observed a gradual, but significant decrease in prevalence of IPIsamong preschool and school-agein Ethiopian in the last two decades with no significant difference between males and females. The prevalence in the most recent 6 years was around 42% compared to 71% in the late 1990s.Place of residence has no effect on the burden of IPIs among preschool and school-age in Ethiopian. Sixteen percent (16%) of preschool and school-age children had concurrent poly-parasitism infections.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- IPIs:

-

Intestinal parasite infections

- MDA:

-

Mass drug administration

- NGOs:

-

Non-governmental organizations

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- STHs:

-

Soil-transmitted helminths

References

Houweling TA, Karim-Kos HE, Kulik MC, Stolk WA, Haagsma JA, Lenk EJ, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in neglected tropical diseases: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(5):e0004546.

Harhay MO, Horton J, Olliaro PL. Epidemiology and control of human gastrointestinal parasites in children. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2010;8(2):219–34.

De Silva NR, Brooker S, Hotez PZ, Montresor A, Engels D, Savioli L. Soiltransmitted helminth infections: updating the global picture. TrendsParasitol. 2003;19(Suppl 12):547–51.

Haftu D, Deyessa N, Agedew E. Prevalence and determinant factors of intestinal parasites among school children in Arba Minch town, southern Ethiopia. Am J Health Res. 2014;2(5):247–54.

Pullan RL, Smith JL, Jasrasaria R, Brooker SJ. Global numbers of infection and disease burden of soil transmitted helminth infections in 2010. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(1):37.

WHO. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: fact sheets. . 2019.

Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459–544.

Kiani H, Haghighi A, Salehi R, Azargashb E. Distribution and risk factors associated with intestinal parasite infections among children with gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2016;9(Suppl1):S80.

Forson AO, Arthur I, Olu-Taiwo M, Glover KK, Pappoe-Ashong PJ, Ayeh-Kumi PF. Intestinal parasitic infections and risk factors: a cross-sectional survey of some school children in a suburb in Accra, Ghana. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):485.

Faria CP, Zanini GM, Dias GS, da Silva S, de Freitas MB, Almendra R, et al. Geospatial distribution of intestinal parasitic infections in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) and its association with social determinants. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(3):e0005445.

AL-Megrin W. Risk factors among preschool children in Riyadh. Saudi Arabia Res J Parasitol. 2015;10(1):31–41.

Mehraj V, Hatcher J, Akhtar S, Rafique G, Beg MA. Prevalence and factors associated with intestinal parasitic infection among children in an urban slum of Karachi. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3680.

Mwale K, Siziya S. Intestinal infestations in under-five children in Zambia. Int J MCH AIDS. 2015;4(2):40.

Nyantekyi LA, Legesse M, Belay M, Tadesse K, Manaye K, Macias C, et al. Intestinal parasitic infections among under-five children and maternal awareness about the infections in Shesha Kekele, Wondo Genet, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Health Dev. 2010;24(3):185–90.

Asfaw ST, Giotom L. Malnutrition and enteric parasitoses among under-five children in Aynalem Village, Tigray. Ethiopian J Health Dev. 2000;14(1):67–75.

Zemene T, Shiferaw MB. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections in children under the age of 5 years attending the Debre Birhan referral hospital, north Shoa, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):58.

Mulatu G, Zeynudin A, Zemene E, Debalke S, Beyene G. Intestinal parasitic infections among children under five years of age presenting with diarrhoeal diseases to two public health facilities in Hawassa, South Ethiopia. Infect Dis Pov. 2015;4(1):49.

Degarege A, Erko B. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among children under five years of age with emphasis on Schistosoma mansoni in Wonji Shoa sugar estate, Ethiopia. PloS One. 2014;9(10):e109793.

Mekonnen HS, Ekubagewargies DT. Prevalence and factors associated with intestinal parasites among under-five children attending Woreta health center, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):256.

Gizaw Z, Adane T, Azanaw J, Addisu A, Haile D. Childhood intestinal parasitic infection and sanitation predictors in rural Dembiya, Northwest Ethiopia. Environ Health Prev Med. 2018;23(1):26.

Beyene G, Tasew H. Prevalence of intestinal parasite, Shigella and Salmonella species among diarrheal children in Jimma health center, Jimma Southwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2014;13(1):10.

Nwosu A. The community ecology of soil-transmitted helminth infections of humans in a hyperendemic area of southern Nigeria. Ann Tropical Med Parasitol. 1981;75(2):197–203.

Dudlová A, Juriš P, Jurišová S, Jarčuška P, Krčméry V. Epidemiology and geographical distribution of gastrointestinal parasitic infection in humans in Slovakia. Helminthologia. 2016;53(4):309–17.

Nguyen NL, Gelaye B, Aboset N, Kumie A, Williams MA, Berhane Y. Intestinal parasitic infection and nutritional status among school children in Angolela, Ethiopia. J Prev Med Hygiene. 2012;53(3):157.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Atkins D, Eccles M, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Henry D, Hill S, et al. Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations I: critical appraisal of existing approaches the GRADE working group. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):38.

Fekadu D, Petros B, Kebede A. Hookworm species distribution among school children in Asendabo town, Jimma Zone, South West Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Health Sci. 2008;18(2):53–56.

Nute AW, Endeshaw T, Stewart AE, Sata E, Bayissasse B, Zerihun M, et al. Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminths and Schistosoma mansoni among a population-based sample of school-age children in Amhara region, Ethiopia. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11(1):431.

Alamir M, Awoke W, Feleke A. Intestinal parasites infection and associated factors among school children in Dagi primary school, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. Health. 2013;5(10):1697.

Assefa T, Woldemichael T, Dejene A. Intestinal parasitism among students in three localities in south Wello, Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Health Dev. 1998;12(3):231.

Desalegn A, Mossie A, Gedefaw L. Nutritional iron deficiency anemia: magnitude and its predictors among school age children, Southwest Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114059.

Fentie T, Erqou S, Gedefaw M, Desta A. Epidemiology of human fascioliasis and intestinal parasitosis among schoolchildren in Lake Tana Basin, Northwest Ethiopia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2013;107(8):480–6.

Haileamlak A. Intestinal parasites in asymptotic children in Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Health Sci. 2005;15:2.

Alemu A, Atnafu A, Addis Z, Shiferaw Y, Teklu T, Mathewos B, et al. Soil transmitted helminths and Schistosoma mansoni infections among school children in Zarima town, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):189.

Amare B, Ali J, Moges B, Yismaw G, Belyhun Y, Gebretsadik S, et al. Nutritional status, intestinal parasite infection and allergy among school children in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13(1):7.

Ayalew A, Debebe T, Worku A. Prevalence and risk factors of intestinal parasites among Delgi school children, North Gondar, Ethiopia. J Parasitol Vector Biol. 2011;3(5):75–81.

Legesse M, Erko B. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among schoolchildren in a rural area close to the southeast of Lake Langano, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 18. 2004;116:120.

Merid Y, Hegazy M, Mekete G, Teklemariam S. Intestinal helminthic infection among children at lade Awassa area, South Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2001;15(1):31–8.

Tadesse G. The prevalence of intestinal helminthic infections and associated risk factors among school children in Babile town, eastern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2005;19(2):140–7.

Degarege A, Erko B. Association between intestinal helminth infections and underweight among school children in Tikur Wuha elementary school, northwestern Ethiopia. J Infect Public Health. 2013;6(2):125–33.

Jejaw A, Zemene E, Alemu Y, Mengistie Z. High prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni and other intestinal parasites among elementary school children in Southwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):600.

King JD, Endeshaw T, Escher E, Alemtaye G, Melaku S, Gelaye W, et al. Intestinal parasite prevalence in an area of Ethiopia after implementing the SAFE strategy, enhanced outreach services, and health extension program. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(6):e2223.

Tulu B, Taye S, Amsalu E. Prevalence and its associated risk factors of intestinal parasitic infections among Yadot primary school children of south eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):848.

Erosie L, Merid Y, Ashiko A, Ayine M, Balihu A, Muzeyin S, et al. Prevalence of hookworm infection and haemoglobin status among rural elementary school children in southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2002;16(1):113–5.

Gelaw A, Anagaw B, Nigussie B, Silesh B, Yirga A, Alem M, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and risk factors among schoolchildren at the University of Gondar Community School, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):304.

Jemaneh L. Soil-transmitted helminth infections and Schistosomiasis mansoni in school children from Chilga District, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Health Sci. 2001;11:2.

Mahmud MA, Spigt M, Bezabih AM, Pavon IL, Dinant G-J, Velasco RB. Efficacy of handwashing with soap and nail clipping on intestinal parasitic infections in school-aged children: a factorial cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2015;12(6):e1001837.

Mahmud MA, Spigt M, Mulugeta Bezabih A, Lopez Pavon I, Dinant G-J, Blanco VR. Risk factors for intestinal parasitosis, anaemia, and malnutrition among school children in Ethiopia. Pathogens Global Health. 2013;107(2):58–65.

Reji P, Belay G, Erko B, Legesse M, Belay M. Intestinal parasitic infections and malnutrition amongst first-cycle primary schoolchildren in Adama, Ethiopia. Afr J Primary Health Care Family Med. 2011;3:1.

Roma B, Worku S. Magnitude of Schistosoma mansoni and intestinal helminthic infections among school children in Wondo-genet Zuria, southern Ethiopa. Ethiop J Health Dev. 1997;11:125–30.

Wegayehu T, Adamu H, Petros B. Prevalence of Giardia duodenalis and Cryptosporidium species infections among children and cattle in north Shewa zone, Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):419.

Adamu H, Endeshaw T, Teka T, Kifle A, Petros B. The prevalence of intestinal parasites in paediatric diarrhoeal and non-diarrhoeal patients in Addis Ababa hospitals, with special emphasis on opportunistic parasitic infections and with insight into the demographic and socio-economic factors. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2006;20(1):39–46.

Belyhun Y, Medhin G, Amberbir A, Erko B, Hanlon C, Alem A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for soil-transmitted helminth infection in mothers and their infants in Butajira, Ethiopia: a population based study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):21.

Dejenie T, Asmelash T, Teferi M. Intestinal helminthes infections and re-infections with special emphasis on schistosomiasis mansoni in Waja, North Ethiopia. Momona Ethiopian J Sci. 2009;1(2):39–46.

Kidane E, Menkir S. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and their associations with anthropometric measurements of school children in selected primary schools. Wukro Town, Eastern Tigray, Ethiopia: Haramaya University; 2012.

Legesse L, Erko B, Hailu A. Current status of intestinal Schistosomiasis and soiltransmitted helminthiasis among primary school children in Adwa Town, Northern Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Health Dev. 2010;24(3):4–16.

Mathewos B, Alemu A, Woldeyohannes D, Alemu A, Addis Z, Tiruneh M, et al. Current status of soil transmitted helminths and Schistosoma mansoni infection among children in two primary schools in North Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):88.

Alemayehu B, Tomass Z, Wadilo F, Leja D, Liang S, Erko B. Epidemiology of intestinal helminthiasis among school children with emphasis on Schistosoma mansoni infection in Wolaita zone, southern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):587.

Assefa A, Dejenie T, Tomass Z. Infection prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni and associated risk factors among schoolchildren in suburbs of Mekelle city, Tigray, northern Ethiopia. Momona Ethiopian J Sci. 2013;5(1):174–88.

Dejenie T, Petros B. Irrigation practices and intestinal helminth infections in southern and central zones of Tigray. Ethiopian J Health Dev. 2009;23(1):587. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12889-017-4499-x

Gashaw F, Aemero M, Legesse M, Petros B, Teklehaimanot T, Medhin G, et al. Prevalence of intestinal helminth infection among school children in Maksegnit and Enfranz towns, northwestern Ethiopia, with emphasis on Schistosoma mansoni infection. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8(1):567.

Mengist HM, Taye B, Tsegaye A. Intestinal parasitosis in relation to CD4+ T cells levels and anemia among HAART initiated and HAART naive pediatric HIV patients in a model ART center in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PloS One. 2015;10(2):e0117715.

Tekeste Z, Belyhun Y, Gebrehiwot A, Moges B, Workineh M, Ayalew G, et al. Epidemiology of intestinal schistosomiasis and soil transmitted helminthiasis among primary school children in Gorgora, Northwest Ethiopia. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2013;3(1):61–4.

Terefe A, Shimelis T, Mengistu M, Hailu A, Erko B. Schistosomiasis mansoni and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in Bushulo village, southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2011;25(1):46–50.

Wale M, Wale M, Fekensa T. The prevalence of intestinal helminthic infections and associated risk factors among school children in Lumame town, northwest, Ethiopia. J Parasitol Vector Biol. 2014;6(10):156–65.

Aiemjoy K, Gebresillasie S, Stoller NE, Shiferaw A, Tadesse Z, Chanyalew M, et al. Epidemiology of soil-transmitted helminth and intestinal protozoan infections in preschool-aged children in the Amhara region of Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hygiene. 2017;96(4):866–72.

Alemu M, Hailu A, Bugssa G. Prevalence of intestinal schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis among primary schoolchildren in Umolante district, South Ethiopia. Clin Med Res. 2014;3(6):174–80.

Begna T, Solomon T, Yohannes ZENEBEEA. Intestinal parasitic infections and nutritional status among primary school children in Delo-mena district, south eastern Ethiopia. Iran J Parasitol. 2016;11(4):549.

Dejenie T, Asmelash T. Schistosomiasis mansoni among school children of different water source users in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Momona Ethiopian J Sci. 2010;2(1):866–72.

Teklemariam A, Dejenie T, Tomass Z. Infection prevalence of intestinal helminths and associated risk factors among schoolchildren in selected kebeles of Enderta district, Tigray, northern Ethiopia. J Parasitol Vector Biol. 2014;6(11):166–73.

Firdu T, Abunna F, Girma M. Intestinal protozoal parasites in diarrheal children and associated risk factors at Yirgalem hospital, Ethiopia: a case-control study. Int Scholarly Res Notices. 2014;2014:549–58.

Tefera E, Belay T, Mekonnen SK, Zeynudin A, Belachew T. Prevalence and intensity of soil transmitted helminths among school children of Mendera elementary school, Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;27:49–60.

Unasho A. An investigation of intestinal parasitic infections among the asymptomatic children in, southern Ethiopia. Int J Child Health Nutr. 2013;2(3):212–22.

Yimam Y, Degarege A, Erko B. Effect of anthelminthic treatment on helminth infection and related anaemia among school-age children in northwestern Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):613.

Abdi M, Nibret E, Munshea A. Prevalence of intestinal helminthic infections and malnutrition among schoolchildren of the Zegie peninsula, northwestern Ethiopia. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10(1):84–92.

Abera A, Nibret E. Prevalence of gastrointestinal helminthic infections and associated risk factors among schoolchildren in Tilili town, Northwest Ethiopia. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2014;7(7):525–30.

Wegayehu T, Karim MR, Li J, Adamu H, Erko B, Zhang L, et al. Multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis isolates from children in Oromia special zone, Central Ethiopia. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16(1):89.

Abossie A, Seid M. Assessment of the prevalence of intestinal parasitosis and associated risk factors among primary school children in Chencha town, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):166.

Hailegebriel T. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and associated risk factors among students at Dona Berber primary school, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):362.

Alemu G, Aschalew Z, Zerihun E. Burden of intestinal helminths and associated factors three years after initiation of mass drug administration in Arbaminch Zuria district, southern Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):435.

Alemu A, Tegegne Y, Damte D, Melku M. Schistosoma mansoni and soil-transmitted helminths among preschool-aged children in Chuahit, Dembia district, Northwest Ethiopia: prevalence, intensity of infection and associated risk factors. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):422.

Alemu G, Abossie A, Yohannes Z. Current status of intestinal parasitic infections and associated factors among primary school children in Birbir town, southern Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):270.

Bajiro M, Dana D, Ayana M, Emana D, Mekonnen Z, Zawdie B, et al. Prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni infection and the therapeutic efficacy of praziquantel among school children in Manna District, Jimma zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(1):560.

Amor A, Rodriguez E, Saugar JM, Arroyo A, López-Quintana B, Abera B, et al. High prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis in school-aged children in a rural highland of North-Western Ethiopia: the role of intensive diagnostic work-up. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(1):617.

Gebretsadik D, Metaferia Y, Seid A, Fenta GM, Gedefie A. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection among children under 5 years of age at Dessie referral hospital: cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):771.

Bekana T, Hu W, Liang S, Erko B. Transmission of Schistosoma mansoni in Yachi areas, southwestern Ethiopia: new foci. Infect Dis Pov. 2019;8(1):1.

Diro E, Lynen L, Gebregziabiher B, Assefa A, Lakew W, Belew Z, et al. Clinical aspects of paediatric visceral leishmaniasis in N orth-west E thiopia. Tropical Med Int Health. 2015;20(1):8–16.

Birhanu M, Gedefaw L, Asres Y. Anemia among school-age children: magnitude, severity and associated factors in Pawe town, Benishangul-Gumuz region, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2018;28(3):259–66.

Leta GT, French M, Dorny P, Vercruysse J, Levecke B. Comparison of individual and pooled diagnostic examination strategies during the national mapping of soil-transmitted helminths and Schistosoma mansoni in Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(9):e0006723.

Mekonnen Z, Meka S, Ayana M, Bogers J, Vercruysse J, Levecke B. Comparison of individual and pooled stool samples for the assessment of soil-transmitted helminth infection intensity and drug efficacy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(5):e2189.

Tefera E, Mohammed J, Mitiku H. Intestinal helminthic infections among elementary students of Babile town, eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20(1):259–66.

Hailu T, Alemu M, Abera B, Mulu W, Yizengaw E, Genanew A, et al. Multivariate analysis of factors associated with Schistosoma mansoni and hookworm infection among primary school children in rural Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2018;4:4.

Alemayehu B, Tomass Z. Schistosoma mansoni infection prevalence and associated risk factors among schoolchildren in Demba Girara, Damot Woide District of Wolaita zone, southern Ethiopia. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2015;8(6):457–63.

Ali I, Mekete G, Wodajo N. Intestinal parasitism and related risk factors among students of Asendabo elementary and junior secondary school south western Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 1999;13(2):157–62.

Jemaneh L. Intestinal helminth infections in schoolchildren in Gonder town and surrounding areas, Northwest Ethiopia. SINET: Ethiopian J Sci. 1999;22(2):209–20.

Debalke S, Worku A, Jahur N, Mekonnen Z. Soil transmitted helminths and associated factors among schoolchildren in government and private primary school in Jimma town, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2013;23(3):237–44.

Dejene T. Impact of irrigation on the prevalence of intestinal parasite infections with emphasis on schistosomiasis in Hintallo-Wejerat, North Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Health Sci. 2008;18(2):457–63.

Abera B, Alem G, Yimer M, Herrador Z. Epidemiology of soil-transmitted helminths, Schistosoma mansoni, and haematocrit values among schoolchildren in Ethiopia. J Infect Dev Countries. 2013;7(03):253–60.

Kabeta A, Assefa S, Hailu D, Berhanu G. Intestinal parasitic infections and nutritional status of pre-school children in Hawassa Zuria District, South Ethiopia. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2017;11(31):1243–51.

Shumbej T, Belay T, Mekonnen Z, Tefera T, Zemene E. Soil-transmitted helminths and associated factors among pre-school children in Butajira town, south-Central Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0136342.

Tadege B, Shimelis T. Infections with Schistosoma mansoni and geohelminths among school children dwelling along the shore of the Lake Hawassa, southern Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181547.

Asemahagn MA. Parasitic infection and associated factors among the primary school children in Motta town, western Amhara, Ethiopia. Am J Public Health Res. 2014;2(6):248–54.

Teshale T, Belay S, Tadesse D, Awala A, Teklay G. Prevalence of intestinal helminths and associated factors among school children of Medebay Zana wereda; North Western Tigray, Ethiopia 2017. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):444.

Gh Y, Degarege A, Erko B. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among children under five years of age with emphasis on Schistosoma mansoni in Wonji Shoa Sugar Estate, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109793.

Samuel F. Status of soil-transmitted helminths infection in Ethiopia. Am J Health Res. 2015;3(3):170–6.

Karshima SN. Prevalence and distribution of soil-transmitted helminth infections in Nigerian children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Pov. 2018;7(1):69.

Emile N, Bosco NJ, Karine B. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and associated risk factors among Kigali Institute of Education students in Kigali, Rwanda. Trop Biomed. 2013;30(4):718–26.

Gabrielli A, Ramsan M, Naumann C, Tsogzolmaa D, Bojang B, Khoshal M, et al. Soil-transmitted helminths and haemoglobin status among afghan children in world food Programme assisted schools. J Helminthol. 2005;79(4):381–4.

Al-Kafri A, Harba A. Intestinal parasites in basic education pupils in urban and rural Idlb. J Lab Diag. 2009;5:2.

Mezeid N, Shaldoum F, Al-Hindi AI, Mohamed FS, Darwish ZE. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among the population of the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among the population of the Gaza Strip, Palestine. 2014;60(4). https://idpjournal.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s40249-018-0451-2

Tchuenté L-AT, Ngassam RIK, Sumo L, Ngassam P, Noumedem CD, DDoL N, et al. Mapping of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in the regions of centre, east and west Cameroon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(3):e1553.

Staudacher O, Heimer J, Steiner F, Kayonga Y, Havugimana JM, Ignatius R, et al. Soil-transmitted helminths in southern highland R wanda: associated factors and effectiveness of school-based preventive chemotherapy. Tropical Med Int Health. 2014;19(7):812–24.

Daryani A, Hosseini-Teshnizi S, Hosseini S-A, Ahmadpour E, Sarvi S, Amouei A, et al. Intestinal parasitic infections in Iranian preschool and school children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Trop. 2017;169:69–83.

Okyay P, Ertug S, Gultekin B, Onen O, Beser E. Intestinal parasites prevalence and related factors in school children, a western city sample-Turkey. BMC Public Health. 2004;4(1):64.

Monib M, Hassan A, Attia R, Khalifa M. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among children attending Assiut University Chil-dren’s hospital, Assiut, Egypt. J Adv Parasitol. 2016;3(4):125–31.

Ouermi D, Karou D, Ouattara I, Gnoula C, Pietra V, Moret R, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasites at saint-Camille medical center in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso), 1991 to 2010. Medecine et Sante Tropicales. 2012;22(1):40–4.

Kunwar R, Acharya L, Karki S. Decreasing prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among school-aged children in Nepal: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2016;110(6):324–32.

de Oliveira Serra A, Aparecida M, CdS C, Coêlho B, Castelo Z, de Castro Rodrigues NL, et al. Comparison between two decades of prevalence of intestinal parasitic diseases and risk factors in a Brazilian urban centre. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2015;2015:546705.

Karagiannis-Voules D-A, Biedermann P, Ekpo UF, Garba A, Langer E, Mathieu E, et al. Spatial and temporal distribution of soil-transmitted helminth infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and geostatistical meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):74–84.

Jayarani K, Sandhya-rani T, Jayaranjani K. Intestinal parasitic infections in preschool and school going children from rural area in Puducherry. Curr Res Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;2(4):406–9.

Workneh T, Esmael A, Ayichiluhm M. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and associated factors among Debre Elias primary schools children, east Gojjam zone, Amhara region, North West Ethiopia. J Bacteriol Parasitol. 2014;15(1):1–5.

Kattula D, Sarkar R, Ajjampur SSR, Minz S, Levecke B, Muliyil J, et al. Prevalence & risk factors for soil transmitted helminth infection among school children in South India. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139(1):76.

Oninla S, Owa J, Onayade A, Taiwo O. Intestinal helminthiases among rural and urban schoolchildren in South–Western Nigeria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2007;101(8):705–13.

Mareeswaran N, Savitha A, Gopalakrishnan S. Prevalence of intestinal parasites among urban and rural population in Kancheepuram district of Tamil Nadu. Int J Commun Med Public Health. 2018;5(6):2585–9.

Lwanga F, Kirunda BE, Orach CG. Intestinal helminth infections and nutritional status of children attending primary schools in Wakiso District, Central Uganda. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(8):2910–21.

Agbolade OM, Agu NC, Adesanya OO, Odejayi AO, Adigun AA, Adesanlu EB, et al. Intestinal helminthiases and schistosomiasis among school children in an urban center and some rural communities in Southwest Nigeria. Kor J Parasitol. 2007;45(3):233.

Phiri K, Whitty C, Graham S, Ssembatya-Lule G. Urban/rural differences in prevalence and risk factors for intestinal helminth infection in southern Malawi. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2000;94(4):381–7.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Kefiyalew Getahun for his contribution in constructing geographical map of Ethiopia.

Funding

We did not receive any funding support for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LCH and ZM conceived the study. LCH and YA extracted the data, and independently decided for inclusion or exclusion, and in events of disagreement, ZM helped to resolve. LCH and DE performed all the statistical analyses. LCH and YA prepared manuscript with the help from DE. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

None applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Forest plot showing prevalence of intestinal parasite infections among rural preschool and school-age children in Ethiopia.

Additional file 2.

Forest plot showing prevalence of intestinal parasite infections among Urban Ethiopia children.

Additional file 3.

Forest plot showing prevalence of intestinal parasite infections among male Ethiopian children.

Additional file 4.

Forest plot showing prevalence of intestinal parasite infections among female Ethiopian children.

Additional file 5.

Forest plot showing prevalence poly-parasitism infections among Ethiopian children.

Additional file 6.

Forest plot showing prevalence intestinal parasite infections with single species of parasite among Ethiopian children.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chelkeba, L., Mekonnen, Z., Alemu, Y. et al. Epidemiology of intestinal parasitic infections in preschool and school-aged Ethiopian children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 20, 117 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8222-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8222-y