Abstract

This study focuses on classifying multiple sessions of loving kindness meditation (LKM) and non-meditation electroencephalography (EEG) data. This novel study focuses on using multiple sessions of EEG data from a single individual to train a machine learning pipeline, and then using a new session data from the same individual for the classification. Here, two meditation techniques, LKM-Self and LKM-Others were compared with non-meditation EEG data for 12 participants. Among many tested, three BCI pipelines we built produced promising results, successfully detecting features in meditation/ non-meditation EEG data. While testing different feature extraction algorithms, a common neural network structure was used as the classification algorithm to compare the performance of the feature extraction algorithms. For two of those pipelines, Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) and Short Time Fourier Transform (STFT) were successfully used as feature extraction algorithms where both these algorithms are significantly new for meditation EEG. As a novel concept, the third BCI pipeline used a feature extraction algorithm that fused the features of CSP and STFT, achieving the highest classification accuracies among all tested pipelines. Analyses were conducted using EEG data of 3, 4 or 5 sessions, totaling 3960 tests on the entire dataset. At the end of the study, when considering all the tests, the overall classification accuracy using SCP alone was 67.1%, and it was 67.8% for STFT alone. The algorithm combining the features of CSP and STFT achieved an overall classification accuracy of 72.9% which is more than 5% higher than the other two pipelines. At the same time, the highest mean classification accuracy for the 12 participants was achieved using the pipeline with the combination of CSP STFT algorithm, reaching 75.5% for LKM-Self/ non-meditation for the case of 5 sessions of data. Additionally, the highest individual classification accuracy of 88.9% was obtained by the participant no. 14. Furthermore, the results showed that the classification accuracies for all three pipelines increased with the number of training sessions increased from 2 to 3 and then to 4. The study was successful in classifying a new session of EEG meditation/ non-meditation data after training machine learning algorithms using a different set of session data, and this achievement will be beneficial in the development of algorithms that support meditation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

1.1 Background of the study

In recent years, meditation has gained significant popularity among people due to several reasons including, increase in scientific research on meditation [1, 2], publicity on evidence of many mental health/ physical health/ social benefits gained when doing meditation [3,4,5], improvements in technological devices/ apps that supports meditation [6,7,8], certain schools, universities, workplaces, hospitals, prisons, sports teams introducing meditation for their stakeholders [9, 10], not to mention increased stress levels in many people in the modern world [11]. Some scientific methods used in the study of meditation include neuroimaging techniques such as EEG (Electroencephalography) [12], fMRI (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) [13], PET (Positron Emission Tomography) [14], fNIRS (Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy) [15], Physiological Measurements such as Heart Rate Variability [16], Cortisol Levels [17] and Psychological Assessments such as Questionnaires, and Interviews [18, 19]. Among those various techniques, in this study we used EEG to understand certain meditation/non-meditation characteristics.

Our research interest lies in the contribution to the development of algorithms and software [20, 21] aimed at understating the characteristics of a new meditation session. Understanding these characteristics will allow us to know how progressive a meditation session is [22]. In other words, this type of research could lead to future possibilities of developing algorithms or software that can guide a person [23] towards good progress in meditation. A progress of something must be measured as a value between two instances or locations. In this case, any such progress in meditation for a person must be compared and measured either against a non-meditation session as the baseline or against a previous meditation session as the baseline. This comparison needs be tested independently on individuals first and if it is successful, further studies can then identify common baselines that can be used to compare the progress of any individual. Therefore, as an initial step in understanding these characteristics in a new meditation session, we should be able to distinguish between a meditation session and a non-meditation session [24,25,26] for the same person.

This study involves using multiple-session [27, 28] meditation/ non-meditation EEG data for 12 participants, training machine learning algorithms [29,30,31] using multiple session data for each participant and then, testing the trained algorithms using a new meditation/ non-meditation pair. Here, intra-subject [32] analysis is performed where each algorithm is trained and tested on each participant independently. The use of multiple session meditation/ non-meditation EEG data to classify a new meditation/ non-meditation pair for the same person using machine learning techniques is a novel research concept that was successfully implemented and described in this paper.

1.2 Related work

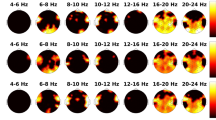

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a method used to study brain functions by recording the electrical activity that occurs when neurons in the brain communicate with each other [33]. When the brain focuses on a specific mind task or is at rest, a large number of neurons work together synchronously sending signals [34]. EEG electrodes [35, 36] are placed on the scalp to detect the voltage patterns resulting from these electrical activities. EEG data collected over a certain duration consists of a series of vibration signals, known as brain waves. One way to study these brain waves is by analyzing their frequencies [37]. The changing brainwave patterns can be broken down into subcategories, each representing a specific frequency. The strength of each frequency varies with the brain wave patterns over time. Research and studies on brainwaves have identified several frequency ranges based on certain common characteristics related to specific mind tasks and brain functions. Although there are some minor differences, the commonly used frequency bands include Delta (0.5–4 Hz), Theta (4–8 Hz), Alpha (8–13 Hz), Beta (13–30 Hz) and Gamma (> 30 Hz) [38,39,40]. There have been significant research showing that the Theta [41,42,43,44] and Alpha [45,46,47] frequency bands are strongly associated with meditation/ non-meditation mind tasks and in our study, we emphasized the importance to these frequency bands.

The brain computer interface (BCI) pipeline [48] consists of the steps of data collection, preprocessing, feature extraction and selection, classification, and application [49, 50]. In preprocessing, cleaning and artifact removal on the collected data are mainly targeted [51, 52]. Sometimes these raw data are directly taken for cleaning, but in some cases, the data are broken down using signal decomposition methods [53, 54] to perform the cleaning efficiently. There are two main types of noise, one type is the noise added from the external environment, such as electromagnetic effects from the surroundings. This noise can be minimized by using a high pass filter to remove unwanted lower frequencies bellow 0.5 Hz and by using a low pass filter to remove unwanted frequencies above 45 Hz [55]. At the same time, there are instances where a 50 Hz band pass filter can be used to eliminate the external electromagnetic noise at that frequency [56]. The second type of noise in EEG data comes from various bodily activities such as eye movement, eye blinking, head or jaw movements, breathing etc [51]. A small portion of this noise will be removed when performing frequency filters, and any remaining artifacts will be removed manually [52]. This can be achieved firstly by plotting channel spectra [57] to identify bad channels or epochs followed by adjusting them. Secondly this is done by running independent component analysis (ICA) [58, 59], to look for components related to errors and to remove them.

After preprocessing, which reduces the noise in the EEG data, the next step in a BCI pipeline is feature extraction [49, 60]. The idea here is to extract important patterns hidden in the EEG data. This is a complex task because, even after cleaning, EEG is known to have a high noise-to-signal ratio. Therefore, to get meaningful information from EEG, advanced signal processing methods such as Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) [61,62,63], Short Time Fourier Transform (STFT) [64, 65], wavelet transform [66], and Event Related Potentials (ERPs) [67] are used. Additionally, Geometrical Features [68], which focus on the spatial and morphological properties of the EEG signals, and Graphical Features [69], which represent connectivity patterns in brain networks, are also employed to extract meaningful insights from EEG data. CSP, as a signal processing method in EEG, focuses on the differences between two mind tasks by creating filters that highlight these differences making it easier to separate the two tasks. CSP is a very powerful EEG feature extraction algorithm mainly used for motor imagery [50, 70], but we adopted CSP with meditation EEG in this study, as well as in our previous study [27]. The full procedure of spatial filters maximizing the variance of the two mind tasks, supported by covariance matrices and their eigen vectors, along with the remaining steps in the CSP process that ranks the spatially filtered features of the two mind tasks, is clearly described in our previous manuscript [27].

STFT [64], on the other hand checks how different frequencies change over time, and this is done by using the mathematical technique known as Fourier Transformation [71, 72] on EEG data. In signal processing, Fourier Transformation decomposes the signal into all the frequencies it is made up of, while indicating the strength of each frequency. In STFT, EEG data is broken down into short overlapping time segments, and for each time segment, the strength of each frequency related to the EEG data are identified using Fourier Transformation. This method is very useful for analyzing EEG data because it allows us to obtain a feature set that shows how brain waves, such as alpha, beta, theta behave over time. In general, a feature extraction algorithm tries to identify a feature set that is unique to the mathematical or statistical approach that algorithm follows. Hence, one feature extraction algorithm may capture certain patterns that another algorithm might fail to capture, and vise versa. Therefore, there can be instances where a fusion of two feature extraction algorithms produces better results than using each algorithm alone. Similar to CSP, although STFT is also a well-established feature extraction algorithm for EEG in general, both of these algorithms are significantly new when it comes to extracting features from meditation EEG.

The next step in a BCI pipeline after feature extraction is classification [73,74,75]. Classification algorithms can be statistical methods, machine learning methods, rule-base methods or a combination of the above [49]. Because of its high accuracy and efficiency with large data, machine learning, subset of artificial intelligence, is gaining high popularity in the research and industrial communities. Random forests, support vector machines, neural networks, decision trees and logistic regression are some of the top-level machine learning algorithms used for classification [29, 30, 76]. Among these, when it comes to classifying complex datasets like EEG, images and voice that require high level abstraction and feature learning capabilities, neural networks [77,78,79,80,81] are on the top of the list. In our study, a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) [75, 76, 82] was used as the neural network for classification, providing a common ground to compare various feature extraction algorithms. An MPL functions similarly to neuron interactions in the brain and consists of an input layer, a couple of hidden layers, and an output layer where each layer has a number of nodes called neurons. MLPs are usually trained using a supervised learning approach [29]. In training, the input data are first passed through the network towards the output, a process known as forward propagation. Here, the network’s output is compared with the actual output, and an error is calculated. This error is then propagated backward, known as backpropagation. The optimization algorithm in the MLP iteratively updates the weights to improve performance. MLPs consist of an activation function that determines whether a neuron should fire or not, and they have a high capacity to approximate complex functions.

Up to now, most of the classification studies on EEG meditation involved using 2 sessions [2, 24, 83]. These two sessions can be from a single person, either during meditation or while not meditating [25, 26]. Another method involves collecting meditation EEG data from novices [84] and experts [85] to compare the two groups. The third method involves using a group of people who are not familiar with meditation and training them for a certain period of time, while simultaneously collecting EEG data at the beginning and end of the training [12]. All these studies are based on the “state” and “trait” characteristics [86] related with meditation, which refers to the changes happening in a person when practicing meditation. These changes have been identified with various methods such as EEG, heartbeat rate, fMRI, fNIRS etc [15, 16, 87]. However, in our study, we focus solely on brainwave patterns using EEG [12, 83, 88] data.

1.3 Meditation in the study

“State” refers to temporary changes that occur in a person while meditating compared to not meditating. “Trait” refers to permanent changes that occur in a person who has been meditating for a long time [89]. Studies have shown that even a person new to meditation can experience significant “state” improvements after a short period of meditation training, such as a couple of months [90, 91]. A characteristic of state changes is that they can manifest quickly for novice meditators. For expert meditators, while state changes still occur, they might be less pronounced over short periods because experts are already at a higher baseline level of meditative experience. Therefore, for very short periods, state changes might appear minimal and less significant in experts compared to novices [12].

For this study an online EEG data collected in a duration of 2 months from 12 expert meditators was used. Since the participants are labeled as experts [92,93,94,95], based on past study records, we assume that there should be a significant “state” characteristic available when comparing meditation and non-meditation instances for these participants. At the same time, since they are expert meditators [92,93,94,95], as past studies indicate, the assumption is made that any improvements in the state characteristic that can happen during this short period of data collection are minimum. Therefore, we expect that there is a small “state” characteristic difference among the sessions of meditation data used for each of these participants. At the same time, we expect a significant state characteristic difference between meditation and non-meditation data. In other words, an assumption is made that for each person, meditation sessions are almost similar in characteristics among themselves, and the non-meditation sessions are also similar in characteristics among themselves, while the two mind tasks will have some significant differences between them. Our aim was to use these differences in “state” characteristic between the two mind tasks as the feature set in our study to train and classify multiple sessions of meditation/ non-meditation EEG data. With these assumptions in mind, the importance of this study is summarized as follows.

1.4 Importance of this study

Using multiple session meditation data to train a machine learning algorithm and classify an unknown session data for a given person is a novel concept that hasn’t been studied so far to the best of our knowledge. At the same time, two feature extraction algorithms CSP and STFT which have not been significantly used with meditation EEG was tested in this study. Most importantly, this study stands out because of using a combined feature set of CSP and STFT in one BCI pipeline for meditation EEG data. Furthermore, with this study we were able to understand how meditation EEG data classification behaves with different number of training session. Thus, this whole study will have a significant impact on future research on developing algorithms to support and guide people to successfully improve their meditation skills.

2 Methods

2.1 Dataset description and overview

An EEG dataset available online was used in this study where the data was collected while practicing loving kindness meditation (LKM) [96, 97]. The dataset DIO is https://doi.org/10.18112/openneuro.ds003816.v1.0.1. A comprehensive description on the dataset has been given in our previous manuscript [27] and a summary of the dataset related to this study is given as follows. The dataset consists of EEG data of 48 participants who have previous experience in meditation. Out of these participants, 15 participants were used to collect data for multiple sessions, that is 8–10 sessions on different days in a period of two months, and the rest of the participants were used to collect data only for a single session. When considering a single data collection session, the EEG data was collected for six mind tasks which produced six EEG data files. The six mind tasks were pre-resting, LKM-Self, LKM-Others, post-resting, visualize self and visualize others. Out of the EEG data collected for these six mind tasks for a single session, only three mind tasks were used in this study, and they are pre-resting (will be referred as non-meditation), LKM-Self, LKM-Others. In pre-resting, the EEG data was collected at the beginning of the session as the first mind task before starting the meditation tasks. LKM-Self and LKM-Others are the two meditation mind tasks where the EEG data was collected when a person has loving, kindness thoughts either towards oneself or for others.

For the current study only a subset of the entire dataset was used according to our research interest. Our research interest was to classify meditation/ non-meditation EEG data for multiple sessions. As the non-meditation task, we used the pre-rest dataset. To compare with this non-meditation task, we used two meditation mind tasks independently and they are LKM-Self and LKM-Others. In other words, we did two studies, one to classify non-meditation/ LKM-Self and the other to classify non-meditation/LKM-Others. Since we were studying the classification of multiple session data, we used the data of the 15 participants where data was collected on 8–10 sessions.

In this study we assumed each of the 15 participants to be independent from one another. Therefore, the classification training and testing was done independently for each participant. This is mainly because we do not have the level of meditation expertise of each participant. Although all the participants are labeled as experts in meditation, in the absence of a measurement to indicate their level of expertise, all participants were considered independently from one another in this study. In this study, machine learning techniques were used to classify each mind task pair (meditation/ non-meditation). When we checked the dataset, we noticed that some session EEG data for some mind tasks had significantly smaller file sizes than others. To give an equal opportunity in an algorithm among the selected session data, and to increase the training and testing strength, we decided to use the largest five EEG files for each mind task for each participant and eliminate smaller data files. Using the largest five files that will contain the highest amount of data for a selected session combination will be useful for training and testing the machine learning algorithms, especially when session data for training and testing are interchanged in different tests. Therefore, as the first step, for each participant we selected the five largest EEG files for each of the three mind tasks non-meditation, LKM-Self and LKM-Others. Here, we only considered the individual file size of each mind task without considering the session number and the total file size for a given session.

2.2 Data preprocessing and cleaning

The next task was to do a cleaning and pre-processing for the selected EEG data. The initial cleaning and the preprocessing on the EEG data was done using EEGLAB [52] in MATLAB and a similar procedure was conducted on each individual EEG file as explained below. After reading an EEG file as the first step, the channel locations [35] were added to the EEGLAB. Then a baseline correction was done on each EEG file by removing the epoch baseline [52]. To detect any bad channels visually, channel spectra [57] was plotted and after identifying the bad channels, they were removed using the “interpolate electrodes” method in EEGLAB [98]. Here, each removed channel was replaced with a new channel by EEGLAB based on the characteristics of the remaining good channels and this is done to make sure the remaining tasks can be done on the total channel size.

After that, the EEG data was filtered using “Basic FIR filter” in EEGLAB while using 2 Hz and 45 Hz as filter boarders. This filtering (low pass/ high pass filters) removed the noise coming from very low frequency and moreover, the 50 Hz noise coming from external electronic devices and electricity from the country that the data was collected [99, 100]. Then, independent component analysis (ICA) [101] was done on the EEG data where ICA was implemented with principal component analysis (PCA) [58, 59] with the value 32 by using the function in EEGLAB. We can observe that PCA has been successfully used with other algorithms for cleaning EEG data, and one such example is MSPCA [53, 54, 102]. Since there are 127 channels in the original dataset, PCA is used for dimensionality reduction to facilitate the smooth process of ICA. By using this function in EEGLAB, the ICA components were plotted and after careful study, bad components were removed to clean the EEG dataset [52]. For each mind task, the cleaned dataset was saved as a new EEG file in “.eeg” format with two supporting files “.vhdr” and “.vmrk”. In the cleaning process we identified that out of 15 participants, there were only 12 participants with good data, the other three participants were observed to have a lot of errors in their EEG dataset and in some cases, the file sizes were comparatively very small. Therefore, from the initial cleaning and preprocessing with EEGLAB, we selected 12 participants out of the 15 total participants. Past studies [103, 104] show that good generalization depends on using a large number of participants, however we conducted our study with the available participant data. In the selected dataset, each participant had three mind tasks with five EEG files per task. Therefore, at the end of this cleaning process, we obtained 180 (12 × 3 × 5) EEG files to be used in the next stage of our study. For the next stage of our study, we used the python environment to develop BCI pipelines [48] and after reading some of these saved files into a one of the developed pipelines, we conducted further processing and analysis.

2.3 BCI pipeline modelling

At this stage we had EEG data for two meditation tasks and one non-meditation mind task. Our aim was to study how effectively a classification can be achieved for meditation/ non-meditation data when using multiple session EEG data. With the available data, we were able to do two studies, one with LKM-Self/ non-meditation EEG data and the other with LKM-Others/ non-meditation EEG data. After the initial cleaning process was done using the EEGLAB, the subsequent stages of data processing were started with the 180 EEG files. In each experiment, the study was conducted individually for each participant using a selected pipeline, and this process was repeated for all the participants for all pipelines. For a single participant 15 EEG files were used, that is comprised of 5 EEG files for the five sessions per each of the three mind tasks and were taken into the BCI pipeline. After reading the file set for a single participant, various feature extraction and classification algorithms were used to see how well they perform [49, 50]. Then the same procedure was conducted on the 12-participant data and the classification accuracies were observed. Based on the performance, certain feature extraction algorithms combined with classification algorithms produced good results. With this knowledge gathered, we finetuned the BCI pipelines that used these algorithms, which displayed good classification accuracies for multiple session EEG data. The following sections elaborates on these steps in modeling the pipelines.

With the initial findings about the most supportive feature extraction and classification algorithms for our task, further studies were conducted after preparing three BCI pipelines. To proceed further, three BCI pipelines were used and for feature extraction we used one out of Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) [61,62,63], Short Time Fourier Transform (STFT) [64, 65] and a fusion of CSP and STFT in each pipeline. Then, each one of these feature extraction algorithms was followed by a neural network [77,78,79] for the classification and the use of neural network gave a common ground to compare performance of the three feature extraction algorithms tested for multiple session meditation EEG data. All three pipelines have a common section at the beginning where the reading of 15 EEG files followed by some basic cleaning conducted on the EEG data. Read_raw_brainvision available in mne package in python was used to read the EEG files [105, 106]. Each file had data of 127 EEG channels and 1 ECG channel in the original dataset. Since the study was done using EEG data, ECG channel was removed, and the remaining EEG channels were used in the montage ‘standard_1005’. As the first step after reading and cleaning the EEG data, each EEG file was broken down into epochs [52] of 2s size with a 1s overlap [107]. The 1s overlap was used to make sure that the data that can get lost when splitting the EEG data is preserved because the splitting end of one epoch will be placed in the middle of the adjacent epoch. The following sections elaborates how each of these pipelines was implemented in a step-by-step approach.

Since the same procedure was conducted for the analysis between the pairs of LKM-Self, versus non-meditation and LKM-Others versus non-meditation, only the explanation relevant to one pair is given. As mentioned above, the first study was to see the classification of multiple session EEG data of LKM-Self and non-meditation. When working with each participant, the largest 5 data files for both LKM-Self sessions and non- meditation sessions were selected for our study. These ten EEG data sessions are independent from each other except they correspond to the two mind tasks performed by the same person. Herein, our aim was to keep two files, one from each mind task for the testing and remaining multiple session files from both mind tasks for the training. When testing, we studied how machine learning methods can be used in classifying a new session with EEG data from the two mind tasks, using the training knowledge obtained from some different sessions. With the available 5 sessions of EEG data, we did the study for 3, 4 and 5 session instances. As the first step, 5 sessions of EEG data available for of LKM-Self and non-meditation were paired based on data size similarity, which means, the largest LKM-Self and non-meditation were paired, then the next two were paired etc. to make sure there will be similar amount of data for both training and testing from both mind tasks. Then these pairs were used in the training and testing. For example, if a random selection is made among these pairs, there will be a chance of having a pair with one as the largest session in one mind task and the other as the smallest session in the other mind task. Therefore, random pairing in this case could negatively impact training and testing with the machine learning algorithms due to biased data sizes and this was eliminated by pairing the mind task EEG data based on size.

2.4 Varied number of sessions

The procedure for using 3 session data was done as follows. As mentioned above, LKM-Self and non-meditation EEG data were paired based on their size. Here, we selected 3 pairs of EEG data, using 2 pairs for the training and the remaining pair for the testing. For each set of 3 pairs, we conducted 3 tests, where one pair becomes the testing data while the other two becomes the training data. Since we had 5 pairs from which we used 3 pairs, we used all possible selection combinations for selecting 3 pairs out of 5 pairs in our experiment. This gave a total of 10 different combinations and per selected combination, we did 3 tests. Therefore, altogether 30 tests were conducted on the 5 pairs of LKM-Self and non-meditation EEG data to test a pipeline developed for selected machine learning training/ testing algorithms for a single participant. This test was repeated for all 12 participants using the developed BCI pipeline.

Next, training and testing was done using 4 pairs of EEG data. In this case 3 pairs were used for the training and the remaining pair was used for the testing. Similar to above procedure, when using 4 pairs, 4 tests were conducted where each time one pair out of the 4 pairs was used as the testing set. Since we had 5 pairs available, we selected 4 pairs and used all possible combinations for selecting these 4 pairs. There are 5 possible ways to select 4 pairs out of 5 and since one such 4 pairs were tested 4 time, a total of 20 tests were conducted on the 5 pairs of LKM-Self and non-meditation EEG data for a selected BCI pipeline. This was repeated for all 12 participant EEG data.

The third test was conducted using all 5 pairs of LKM-Self and non-meditation EEG data. Here, 4 pairs of session data were used for the training and the remaining pair was used for the testing. This was repeated while each time a new pair was used for the testing. In this case a total of 5 tests were conducted for 5 pairs of LKM-Self and non-meditation EEG data for the selected BCI pipeline and the procedure was repeated for the EEG data of all 12 participants. Based on the session size, a total of 55 (30 + 20 + 5) tests were conducted for each participant. This was done on all 12 participants across the 3 pipelines for two meditation mind tasks, resulting in a total of 3960 tests conducted in our entire study (55 tests per participant * 12 participants * 3 pipelines * 2 meditation tasks).

These studies allowed us to understand how multiple session EEG data can be used to train a machine learning algorithm and test the trained algorithm by performing classification on a new session EEG dataset. At the same time, the study allowed us to understand how these machine learning pipelines behave when the number of training sessions increases in a multiple session classification study. This concludes the description on the common section of the three BCI pipelines where the training and testing was done using 3 pairs, 4 pairs and 5 pairs of LKM-Self and non-meditation EEG data. The following section will explain the part where the three BCI pipelines have their unique characteristics.

2.5 Feature extraction and classification

Each of the three BCI pipelines used in our study has their unique characteristics based on how feature extraction algorithms were used in them. In our study, advanced signal processing algorithms were used for the feature extraction and machine learning algorithms were used for the classification. In all three pipelines, neural networks were used for the classification. To be more precise, a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) with two hidden layers with a size of 20 for each layer, a logistic activation function, max_iter = 1000 and random_state = 42 was used in each of the three pipelines for the classification [75, 76, 82]. For the feature extraction in the first pipeline Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) was used and for the second pipeline Short Time Fourier Transform (STFT) was used. Most importantly, for the third pipeline a fusion of CSP and STFT was used as the algorithm for the feature extraction from EEG data.

A pipeline starts by reading a portion of EEG files (the ones saved after cleaned and preprocessed by EEGLAB) for the three mind tasks and splitting them into epochs of 2s. Using this dataset, analysis was done for the pair LKM-Self and non-meditation and for the pair LKM-Others and non-meditation independently. When considering LKM-Self and non-meditation in the pipeline with CSP used for feature extraction, the procedure starts by taking the epochs of 5 sessions for the two mind tasks. Here, depending on how many sessions were used for the analysis, dataset is divided into train and test data, where one pair of session data is used for the testing and the remaining pairs were used for the training. Since it is needed to keep records of both training and testing data, each epoch of data had a label to indicate which mind task each epoch represents. Each data epoch is a 2D (dimension) array where one side represents the number of channels, and the other side represents the individual data elements for a single channel. In this case, there are 127 channels and 2000 data points which contains 1000 Hz data for 2s time interval. In the pipeline, this 2D array dataset for a single epoch is grouped into a 3D array where the number of epochs becomes the magnitude of the third dimension and we had a 1D label set with the size same as the number of epochs, where one label is used to represent each epoch. This 3D dataset with the shape (# of epochs, 127 of channels, 2000 of datapoints) and 1D labels set with the shape (# of epochs) are then processed and reshaped accordingly to satisfy the algorithms used in the pipeline.

As the next step with the CSP pipeline, a covariance matrix [108, 109] was calculated using the training dataset and the corresponding labels where Ledoit-Wolf shrinkage estimator [110] was used for the matrix regularization. Here, as the next step, a CSP object with 4 spatial filters (nfilter = 4) was initialized. Then, the function ‘fit’ was used on the CSP model while using the calculated covariance matrix and the corresponding labels. This step calculates 4 spatial filters that minimize the variance for one mind task while maximizing for the other mind task for the training dataset and after the calculation, this was extracted using the “filters_” function. The result is a 2D array (4, 127) where we have 4 spatial filters per channel and these spatial filters contain the spatial patterns [111] (features hidden in the training dataset) which are most discriminative between the two mind tasks. This result was kept aside to be used shortly.

Then the 3D training and testing datasets with the shape (# of epochs, 127, 2000) were taken and reshaped as 2D arrays (# of epochs x 127, 2000) and principal component analysis (PCA) [58, 59] was applied with (n_components = 127). The datasets were reshaped to 2D because that shape change allowed us to use PCA on the data and PCA was applied on the training/ testing data to reduce the dimensionality [112, 113] from 2000 to 127. The results obtained from PCA were reshaped to obtain 3D arrays of the shape (# of epochs, 127, 127). These two training/ testing arrays were multiplied with the reshaped spatial patterns array described in the above paragraph to get a feature set for training and testing with the shape (# of epochs, 127, 4). These training/ testing feature sets were then reshaped as (# of epochs x 127, 4) along with the corresponding label set to satisfy the shape of the neural network. The MLP we used had 4 input nodes and it had two hidden layers with each one having 20 nodes. While checking various combinations, we noticed that the above pattern gave optimal results, thus it was used. As described above, this experiment was conducted while using 3, 4 and 5 multiple session EEG data. At the same time, this was conducted in classifying LKM-Self, non-meditation pair and also with the pair LKM-Others, non-meditation using the first BCI pipeline (CSP pipeline) we developed.

The second pipeline was developed while using STFT for feature extraction and MLP for the classification. As explained above, the pipeline starts by reading a portion of the cleaned EEG data of the three mind tasks and breaking them into epochs of 2s. At this point the training/ testing data had the shape (# of epochs, 127, 2000) and labels set had the shape (# of epochs). Then the 3D training/ testing data were converted to 3D STFT data. In this case each epoch is broken into multiple timeslots and an average value per frequency value (whole numbers) was calculated for the frequency points from 0 to 45 and the shape of the results were as (# of epochs, 127, 46). These training/ testing features were reshaped into 2D (# of epochs x 127, 46). Then, these feature sets were used in the training and testing of the neural network while changing the range of the frequency used to get the optimal solution. By doing this study, we noticed that the ten frequencies in the range [4:13] gave the best result and it was used in our study. The frequency band 4–8 Hz is referred as Theta [41,42,43,44] and the frequency band 8–13 Hz is referred as Alpha [45,46,47] in brain wave frequency studies. Therefore, the selected frequency range in this study contains information of Theta and Alpha waves of the brainwaves. With this knowledge, we used the training/ testing dataset (# of epochs x 127, 10) along with the corresponding labels in the neural network. Therefore, the MLP in the second pipeline had 10 input nodes and it had two hidden layers with each one having 20 nodes. The STFT pipeline was implemented for 3, 4 and 5 multiple session EEG data and the classification accuracies were calculated for LKM-Self, non-meditation pair and also for the pair LKM-Others and non-meditation.

The third pipeline was modeled with the fusion of CSP and STFT for the features. This algorithm follows the steps of the above two algorithms when using CSP alone and STFT alone to get two feature sets for the training/ testing data. In this pipeline, after following the steps explained with the above two pipelines, we came to the point of having a training/ testing feature set for CSP with the shape of (# of epochs x 127, 4) and a training/ testing feature set for STFT with the shape of (# of epochs x 127, 10). As the next step under this pipeline, we joined these two feature sets to get a combined feature set of CSP and STFT with the shape of (# of epochs x 127, 14). Then, this feature set obtained for the training/ testing data along with the matching label set were used with the neural network with 14 input nodes and did the classification. The MLP in the third pipeline had two hidden layers with each one having 20 nodes. Using the third pipeline (fusion of CSP and STFT) along with the multi-layer perceptron, analysis was conducted to study the classification accuracies for LKM-Self, non-meditation pair and for the pair LKM-Others and non-meditation using the cleaned EEG data. This study was conducted using multiple session EEG data and this was done for multiple sessions of 3, 4 and 5. A summary of the procedure is shown in Fig. 1.

3 Results

The main target of this study was to see how well feature extraction and classification algorithms can be used with multiple session meditation/ non-meditation EEG data. Here, after training a machine learning algorithm using multiple session EEG data, we studied the performance of the trained algorithm in classifying a new meditation/ non-meditation session for the same subject. Data collected for 12 participants was used in this study. The results obtained can be divided into two main parts since one study was conducted using LKM-Self and non-meditation EEG data and the second study was conducted using LKM-Others and non-meditation EEG data. At the same time, the results can be divided based on the three feature extraction methods (CSP, STFT or the fusion of CSP and STFT) used in this study. Furthermore, the results can be divided based on the number of sessions used in this study. We used either 3, 4 or 5 sessions and out of which 2, 3 or 4 sessions were used for the training while using the remaining session pair for the testing. Therefore, with this change in the number of training sessions, we were able to study how classification accuracies changed. In our study, we used Leave-One-Session-Out Cross-Validation, and the average and standard deviation were used to calculate the accuracy and uncertainty for each participant.

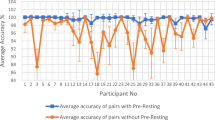

Table 1 shows the average classification accuracies obtained for LKM-Self and non-meditation when using 3 sessions of EEG data for the study where 2 sessions were used for the training and 1 session for the testing. The results were obtained by analyzing the EEG data of the 12 participants using CSP, STFT and a fusion of CSP and STFT as the feature extraction algorithms, and Figs. 2 and 3 demonstrate the performance comparison. Figure 2 graphically shows the results given in Table 1; Fig. 3 gives the normalized classification accuracies that allow us not only to compare performance of the three algorithms for each person, but also to compare this individual change among all participants, which is a visual improvement of Fig. 2. Figure 3 is prepared by setting the lowest classification accuracy among the three algorithms for each person to 0 and the other two accuracies are proportionally plotted by considering the largest change (among all pairwise comparisons for all 12 participants) set to 100, and all the other changes scaled proportionally between 0 and 100. In Fig. 3, participant 12 shows the highest accuracy difference among the three algorithms, while participant 11 shows the lowest accuracy difference among the three algorithms (the top value in the graph is the smallest for participant 11 compared to the top values for all other participants). In the meantime, Table 1 shows that for all participants, the mean classification accuracy for CSP is at 66.7% and for STFT it is 67.3%. For the selected 12 participants, we observed the fusion of CSP and STFT gave a better mean classification accuracy of 72.1%. When considering the performance of CSP alone and STFT alone, we observed almost similar mean accuracies. Out of these 12 participants, 10 participants demonstrated the highest accuracy levels when using CSP and STFT together which is 83.3% of probability of total participants. In terms of CSP alone and STFT alone, the highest accuracy level was demonstrated by only one person in each instance which is a probability of 8.3% of total participants of the study and this is visible in Fig. 3.

Table 2 shows the average classification accuracies obtained for LKM-Others and non-meditation when using 3 sessions of EEG data for the study where 2 sessions were used for the training and 1 session for the testing. The results were obtained using the EEG data of the 12 participants while using CSP, STFT and fusion of CSP and STFT, and Figs. 4 and 5 demonstrate the performance comparison. Figure 4 graphically shows the results given in Table 2; Fig. 5 gives the normalized classification accuracies that allow us to compare performance of the three algorithms for each person and compare this change among all participants. Table 2 shows that for all participants, the mean classification accuracy for CSP is at 65.1% and for STFT it is 65.7%. Furthermore, we observed that the fusion of CSP and STFT demonstrates a better mean classification accuracy of 70.7% for all the participants and this is better than the mean accuracies obtained when using the algorithms alone (difference of 5.0%). When considering the performance of CSP alone and STFT alone, we observed very similar mean accuracies. Out of these 12 participants, 10 participants gave the highest accuracy levels when using CSP and STFT together which is 83.3% of probability in terms of the total number of participants. Regarding CSP alone and STFT alone the highest accuracy level was demonstrated by only one person for each algorithm which is a probability of 8.3% for the study (see Fig. 5).

Table 3 shows the average classification accuracies obtained for LKM-Self and non-meditation when using 4 sessions of EEG data for the study where 3 sessions were used for the training and 1 session for the testing. Here, one of the three algorithms CSP, STFT or fusion of CSP and STFT was used on data available for 12 participants. Figure 6 graphically shows the results given in Table 3; Fig. 7 gives the normalized classification accuracies that allow us to compare performance of the three algorithms for each person and compare this change among all participants and this is a visual improvement of Fig. 6. In Fig. 7 we can observe participant 12 shows the highest accuracy difference among the three algorithms which is given by the fusion of CSP and STFT. Table 3 shows that for the 12 participants, the mean classification accuracy for CSP was 68.4% and for STFT it was 69.1%. For the selected 12 participants, we observed the fusion of CSP and STFT gives the best mean classification accuracy among the three algorithms which is 74.2% for the 12 participants, 5.1% greater than the other two. In the meantime, we observed CSP and STFT alone produced similar mean accuracies. By looking at Fig. 7 we can see that out of the 12 participants, 9 participants showed the highest accuracy level when using CSP and STFT together which is a probability of 75.0% of total participants. At the same time, in this study STFT alone gave the highest accuracy on 2 participants which is 16.7% and CSP alone gave the highest accuracy for 1 person which is 8.3%.

Table 4 shows the average classification accuracies obtained for the 12 participants when using the mind tasks LKM-Others and non-meditation. Here, 4 sessions of EEG data were used for the study where 3 sessions were used for the training and 1 session for the testing. One of the three algorithms CSP, STFT or fusion of CSP and STFT was used in the implementation and Figs. 8 and 9 displays the comparisons of the performances. Figure 8 graphically shows the results given in Table 4; Fig. 9 gives the normalized classification accuracies that allow us to compare performance of the three algorithms for each person and compare this change among all participants. Table 4 shows that for the 12 participants, the highest mean classification accuracy was obtained for the algorithm with the fusion of CSP and STFT, which is 72.0%. When using CSP alone and STFT alone, they were giving slightly lower mean accuracies (~ 5% difference) when compared to the use of fusion of CSP and STFT and those accuracies were 66.2% and 66.8% respectively. Out of these 12 participants, 10 participants demonstrate the highest accuracy level when using CSP and STFT together which is 83.3% of the total study. For both CSP alone and STFT alone, the highest accuracy was demonstrated only by 1 person which is a probability of 8.3% for this study and all this is shown in Fig. 9.

Table 5 shows the average classification accuracies obtained for LKM-Self and non-meditation when using 5 sessions of EEG data for the study where 4 sessions were used for the training and 1 session for the testing. In Table 5, the average classifications accuracies and their errors for the 12 participants are shown for the three algorithms CSP, STFT or fusion of CSP and STFT, and Fig. 10 gives a graphical representation of the results. Figure 11 shows the normalized classification accuracies that demonstrates a good comparison on the performance of the three algorithms for each person and among all participants. Table 5 shows that for the 12 participants, the mean classification accuracy for CSP was 69.5% and for STFT it was 70.4%. For the selected 12 participants, we observed that the fusion of CSP and STFT gave the best mean classification accuracy among the three algorithms which is 75.5%. Here, the performance difference between CSP alone and STFT alone is less than 1.0%. However, when considering CSP and STFT fusion, the accuracy this produced is greater than 5.1% when compared with CSP alone and STFT alone. When studying the Fig. 11, it is observed that out of 12 participants, 10 participants gave the best accuracy level when using CSP and STFT together which is 83.3% of the total participants. CSP alone and STFT alone gave the highest accuracy once per each algorithm and this probability is 8.3%. for the study.

Table 6 shows the average classification accuracies obtained for the 12 participants when using the mind tasks LKM-Others and non-meditation. Here, 5 sessions of EEG data were used for the study where 4 sessions were used for the training and 1 session for the testing. Figures 12 and 13 gives a clear picture of how the classification algorithms work when using the three algorithms CSP, STFT or fusion of CSP and STFT. Table 6 shows that for the selected 12 participants the mean accuracy for the three algorithms CSP, STFT or fusion of CSP and STFT are 66.5%, 67.3 and 73.0% respectively. Here, we can see a 5.7% difference between the highest two results and a 0.8% difference between the lowest two results. At the same time, it is observed that out of the 12 participants, 10 participants obtained the highest classification accuracy when using CSP and STFT together for feature extraction. This probability is 83.3% of the total participants and only one person per instance got the highest accuracy when using CSP alone and STFT alone, which is a probability of 8.3% and this is shown in Fig. 13.

4 Discussion

This study successfully showed that for a given person, multiple session meditation/ non-meditation EEG data can be used for training machine learning algorithms and those trained algorithms can be used to successfully classify a new session of meditation/ non-meditation EEG data for the same person. Although further improvements are needed to increase the classification accuracies, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time an attempt has been made successfully to use multiple session data to train an algorithm and to classify an unknown session of meditation/ non-meditation EEG data. The study was done for two meditation techniques (LKM Self and LKM Others) and one non-meditation mind task. Therefore, two studies were conducted, one for LKM Self & non-meditation EEG data and the second one for LKM Others & non-meditation EEG data. Hence, our findings are supported by two independent studies where EEG data of two meditation tasks were used.

Although the participants used in the data collection were labeled as experts in meditation, the data does not provide the level of meditation expertise as a measurement for these participants. This lack of information pushed us to do only intra-subject analysis and prevents us from doing any inter-subject analysis. For example, if there was a measurement for the expert level of the meditators and some of them fall into the same level, we could have done inter-subject classification by taking multiple session meditation data from those participants and comparing that with multiple session non-meditation data among those same level participants. That would have allowed us to first study on intra-subject multiple session classification and then extend it to inter-subject multiple session classification. On the other hand, if there was a measurement for the expert level of the meditators in the dataset, and moreover, if the participants fall into two or more levels, we could have used that to study the “trait” characteristics of the participants using the level difference values among those participants. Unfortunately, with the limited information available without any values to represent the expert levels, only intra-subject analysis was done where each participant was considered independent from one another.

The majority of the classification studies done in the past with meditation/ non-meditation EEG data were done on two session data, rather than on multiple sessions. However, in our previous study, we introduced the novel research idea or using multiple session EEG data to a certain level. In our previous study, we used EEG data from 5 sessions for the same person, creating separate pools of epochs for meditation and non-meditation EEG data. Then, from that pool we selected a certain percentage randomly for the training and the remaining for the testing. In that case, both training and testing datasets were expected to have epochs of all 5 sessions of meditation and non-meditation EEG data since the data was randomly selected. In this current study, we went a step further where multiple session meditation/ non-meditation EEG data from one person were used for training the algorithms and a different session EEG data from the same person was used in the classification. In the previous study, we showed the occurrence of similar characteristics not only in multiple session meditation EEG data but also in multiple session non-meditation EEG data. However, since in our previous study, we were using data from a pool of data for training and testing, it was not supporting the classification of a new session of meditation/ non-meditation EEG data. In this new study we were able to show that this is achievable, where a new session of meditation/ non-meditation EEG data can be classified by an algorithm trained using a different set of meditation/ non-meditation EEG multiple session data for the same person.

4.1 Analysis based on the type of algorithm used

In this study, three pipelines were used to train and classify multiple session meditation/ non-meditation EEG data. This was achieved using several feature extraction and classification algorithms in the initial stage to see how well the classifications perform. Through initial analysis, we identified that for the classification, a multi-layer perceptron was generating good results, and hence, it was used to proceed further. Since our aim was to identify good feature extraction algorithms, to keep the same ground for comparison, neural network was used as the classification algorithm with different feature extraction algorithms. When checking for various feature extraction algorithms, we identified that CSP and STFT were generating good results. We then introduced a new feature extraction algorithm that fuses CSP and STFT and this new algorithm generated better results than using CSP alone and STFT alone. Hence, results obtained at the end of our study turned out be notable because they proved that multiple session EEG data meditation/ non-meditation tasks from a selected person can successfully classify a new unknown session for that individual. Additionally, the fusion of CSP and STFT produced better results compared to using CSP or STFT alone.

The studies were done on LKM Self/ non-meditation and LKM Others/ non-meditation EEG data independently for three cases of 3, 4 or 5 sessions and out of which 2, 3 or 4 sessions were used for the training while using the remaining session pair for the testing. Tables 1, 3 and 5 show the results for LKM Self/ non-meditation for the use of 2, 3, and 4 training sessions and Tables 2, 4 and 6 show the results for LKM Others/ non-meditation for the use of 2, 3, and 4 training sessions. When checking these tables, it is visible that classification accuracies of certain participants were noticeably higher than some other participants. One obvious reason for this could be due to unexpected noise of some EEG files which persisted even after the multistep comprehensive cleaning. The other possible reason is, for some participants, there might be a big difference in the wave patterns between meditation/ non-meditation EEG data, whereas others may not have much of a difference and this depends on the expert level of the mediators. Past studies have shown that at the start of learning meditation, there will not be much of a difference between meditation and non-meditation brain patterns for novice meditators. But when you consider an expert meditator, you tend to see considerable differences in mind patterns between meditation and non-meditation [92,93,94,95]. However, since we do not have a measurement level that indicates the expert levels of the participants, to compare the results, it cannot be confirmed that the noticeable classification differences among the participants is related to the expert level. Therefore, to compare the performance of the three algorithms, we calculated the mean accuracy for all the 12 participants and this value was used in the comparison of the three algorithms.

When considering LKM Self/ non-meditation classification, the highest mean accuracy was obtained using the algorithm with the fusion of CSP and STFT, for the three instances when using 2, 3 and 4 sessions for training and the results obtained are depicted in Tables 1, 3 and 5 respectively. As shown in Tables 1, 3 and 5, the best results obtained were 72.1%, 74.2% and 75.5% respectively, when using CSP + STFT for feature extraction. When considering the mean classification accuracies calculated for all 12 participants across each of the three training session sizes, for all instances, CSP alone showed the lowest classification accuracies and STFT alone demonstrated slightly higher accuracies compared to CSP alone (with differences of 0.6%, 0.7%, 0.9% for the three session sizes, respectively). On the other hand, CSP + STFT combination significantly outperformed STFT alone in classification accuracies when using 2, 3 and 4 sessions for training, with differences of 4.8%, 5.1% and 5.1%, respectively. While the mean accuracy difference between CSP alone and STFT alone is less than 1%, the mean accuracy of CSP + STFT combination is on the average 5.0% higher than CSP alone and STFT alone for LKM Self/ non-meditation classification and this a significant finding.

When considering LKM Others / non-meditation classification, the highest mean accuracy was obtained when using the algorithm with the fusion of CSP and STFT for the three instances of using 2, 3 and 4 sessions for training. These results are given in Tables 2, 4 and 6 respectively, with mean accuracies of 70.7%, 72.0% and 73.0% for each case. When considering the mean classification accuracies calculated for all 12 participants across each of the three training session sizes, CSP alone gave the lowest classification accuracies and STFT alone showed slightly higher accuracies compared to CSP alone (with differences of 0.6%, 0.6%, 0.8% for the three session sizes, respectively). However, CSP + STFT combination gave the highest mean accuracy across all three session sizes, significantly higher than STFT alone (with differences of 5.0%, 5.2%, 5.7% for the three session sizes, respectively). While the mean accuracy difference between CSP alone and STFT alone is less than 1%, the mean accuracy of the CSP + STFT combination is on average 5.3% higher than CSP alone and STFT alone for LKM Others/ non-meditation classification and this also a significant finding.

The overall average of the classification accuracy when using CSP alone for all instances is calculated as 67.1%. Similarly, overall average of the classification accuracy when using STFT alone for all instances is calculated as 67.8% and when using CSP + STFT combined the result was 72.9%. Therefore, when considering all instances, using CSP alone and STFT alone generated classification accuracies with a difference less than 1%. The results show that the best classification accuracy can be obtained when using the fusion of CSP and STFT for the feature extraction and then using that information in the classification. This classification accuracy is more than 5% greater than using CSP alone and STFT alone and this is a notable increase in the classification accuracy.

4.2 Analysis based on the number of training sessions used

While working on the main research topic that focused on studying how well machine learning algorithms can be used in classifying multiple session meditation/ non-meditation EEG data, by rearranging the results shown in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, a different pattern was observed. This pattern displayed that higher the number of training sessions (training data size), the higher the calculated classification accuracy when using a certain algorithm set for the feature extraction and classification. The classification accuracies shown in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, were generated using the same file size for training while using different algorithms and the results are separated into LKM Self/ non-meditation and LKM Others/ non-meditation. To add an alteration, in this new comparison, all the results were grouped according to the algorithm used, separately for LKM Self/ non-meditation and for LKM Others/ non-meditation. It allowed us to compare the classification accuracies for different numbers of training sessions within a given algorithm and a mind task pair. The results indicated that the increase in the number of training sessions used in the machine learning algorithm increases the average classification accuracy and the following section explains this for each algorithm and meditation type.

Table 7 shows the average classification accuracies obtained for LKM-Self and non-meditation when using the algorithm CSP in the pipeline for the three cases of 3 sessions, 4 sessions and 5 sessions of data and the Fig. 14 shows the results graphically. When using 3, 4, and 5 sessions, 2, 3, and 4 sessions were used respectively for the training and the remaining one session was used in the testing. The mean classification accuracies for these three cases are 66.7%, 68.4% and 69.5% respectively and this suggests that there is an increase in the mean classification accuracy with the increase in the number of training sessions. Figure 15 gives the normalized classification accuracies of the Table 7, and this figure allows us not only to compare classification accuracies for the three session sizes for each person, but also to compare this change among all participants and this is a visual improvement of Fig. 14. Figure 15 is prepared by putting the lowest classification accuracy among the three for each participant to 0 and the other two are proportionally plotted by giving the largest change among all participants to have a value 100, and all the other values changing proportionally in between 0 and 100. When considering the individual participants, using 4 sessions has increased the classification accuracy of all 12 participants when compared with 3 sessions and in other words 100% of total participants. At the same time, using 5 sessions has increased the classification accuracy for 8 participants out of 12 when compared with 4 sessions, and this is a 66.7% increase.

Table 8 shows the average classification accuracies obtained for LKM-Self and non-meditation when using the algorithm STFT in the pipeline for the three cases of 3 sessions, 4 sessions and 5 sessions of data and Fig. 16 shows the results graphically. The mean classification accuracies for the three cases are 67.3%, 69.1% and 70.4% respectively and this indicates an increase in the mean classification accuracy with the increase in the training data size. Figure 17 gives the normalized classification accuracies of the Table 8, and this figure allows us to compare classification accuracies for the three session sizes for each person, as well as the change among all participants and this is a visual improvement of Fig. 16. When considering the individual participants, using 4 sessions has increased the classification accuracy of all 12 participants when compared with 3 sessions and this is a 100% increase. Similarly, using 5 sessions has increased the classification accuracy of all 12 participants when compared with 4 sessions, and this is also a 100% increase.

Table 9 shows the average classification accuracies obtained for LKM-Self and non-meditation when using the algorithm with CSP and STFT fusion in the pipeline for the three cases of 3 sessions, 4 sessions and 5 sessions of data and the Fig. 18 shows the results graphically. The mean classification accuracies for the three cases are 72.1%, 74.2% and 75.5% respectively and this shows an increase in the mean classification accuracy with the increase in the number of training sessions. Figure 19 demonstrates the normalized classification accuracies of the Table 9 and by observing Fig. 19 we can see that using 4 sessions has increased the classification accuracy for 11 participants out of 12 when compared with 3 sessions and this is a 91.7% increase. Similarly, using 5 sessions has increased the classification accuracy for 11 participants out of 12 when compared with 4 sessions, and this is a 91.7% increase.

Table 10 shows the average classification accuracies obtained for LKM-Others and non-meditation when using the algorithm CSP in the pipeline for the three cases of 3 sessions, 4 sessions and 5 sessions of data and the Fig. 20 shows the results graphically. The mean classification accuracies for the three cases are 65.1%, 66.2% and 66.5% respectively and this indicates an increase in the mean classification accuracy with the increase in the number of training sessions. Normalized classification accuracies of the Table 10 given in Fig. 21, demonstrates that using 4 sessions has increased the classification accuracy for 8 participants out of 12 when compared with 3 sessions and this is a 66.7% increase. Similarly, using 5 sessions has increased the classification accuracy for 8 participants out of 12 when compared with 4 sessions, and this is also a 66.7% increase.

Table 11 shows the average classification accuracies obtained for LKM-Others and non-meditation when using the algorithm STFT in the pipeline for the three cases of 3 sessions, 4 sessions and 5 sessions of data and the Fig. 22 shows the results graphically. The mean classification accuracies for the three cases are 65.7%, 66.8% and 67.3% respectively and this indicates an increase in the mean classification accuracy when increasing the number of training sessions. Furthermore, normalized classification accuracies of the Table 11 given in Fig. 23, demonstrates that using 4 sessions has increased the classification accuracy for 10 participants out of 12 when compared with 3 sessions and this is 83.3% of the total participants. Similarly, using 5 sessions has increased the classification accuracy for 10 participants out of 12 when compared with 4 sessions, and this is also an 83.3% increase.

Table 12 shows the average classification accuracies obtained for LKM-Others and non-meditation when using the algorithm CSP and STFT fusion in the pipeline for the three cases of 3 sessions, 4 sessions and 5 sessions of data and Fig. 24 shows the results graphically. The mean classification accuracies for the three cases are 70.7%, 72.0% and 73.0% respectively and this indicates an increase in the mean classification accuracy with the increase of the number of training sessions. Moreover, normalized classification accuracies of the Table 12 given in Fig. 25, demonstrates that using 4 sessions has increased the classification accuracy for 11 participants out of 12 when compared with 3 sessions and this is an increase of 91.7%. At the same time, using 5 sessions has increased the classification accuracy for 10 participants out of 12 when compared with 4 sessions, and this is an increase of 83.3%.

When summarizing the above results, the lowest mean accuracy was obtained when using 3 sessions in the study. At the same time, the highest mean accuracy was obtained when using 5 sessions whereas using 4 sessions stood at a middle mean accuracy level. This shows that when the number of training sessions increases, the classification accuracy increases. Furthermore, the following section shows how this pattern behaves for individual participant classification accuracies. Out of 72 instances for the 12 participants, in 64 instances, using 4 sessions was giving a higher classification accuracy than using 3 sessions and the percentage of this is 88.9% when training the machine learning algorithms. Similarly, out of 72 instances for the 12 participants, in 59 instances, using 5 sessions was giving a higher classification accuracy than using 4 sessions and the percentage of this is 81.9%. These 2% results further prove that use of more sessions for training a machine learning algorithm increases the classification accuracy of that algorithm.

4.3 Limitations of the study and future work

The study was conducted using an online EEG dataset and some limitations were based on the characteristics of the dataset. Our interest was only with the multiple session EEG data which has been collected for 15 participants for 8–10 sessions. Due to errors in some files and due to having comparatively smaller file sizes, our analysis was conducted only for 12 participants using the largest 5 files for each mind task and our analysis was limited to these boundaries. At the same time, although the participants were labeled as experts in meditation, since there was no indication of this expert level as a value, we only did intra-subject analysis, and we could not do any inter-subject analysis. Also, as described previously, lack of quantified meditation expert level of the participants forced us to study only the “state” characteristic of the meditation EEG data and we were not able to study the “trait” characteristic of the meditation EEG data.

Since this is the first time a study was conducted to classify multiple session meditation/ non- meditation EEG data, further studies can be conducted for improving the classification accuracies so the studies can support the identification of new meditation/ non-meditation states with much ease. At the same time, for future work, if multiple session EEG data can be collected from participants in the same expert level, such data can be used to study if machine learning can be used for classifying multiple session EEG data as an inter-subject analysis. Similarly, if the data was collected for participants with multiple expert levels, then this can be used to study the “trait” characteristic of the meditation EEG data.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we were able to demonstrate successful classification of multiple session meditation/ non-meditation EEG data. LKM-Self, non-meditation pair and LKM-Others, non-meditation pair were independently tested here. While keeping a neural network in all instances as the classification algorithm, the features of meditation EEG were successfully extracted using CSP, STFT and fusion of CSP and STFT. Use of CSP and STFT for meditation EEG is a significantly new approach, and fusion of CSP and STFT notably improved the results. Most importantly, by conducting 3960 tests, we were able to show that for a given person, after training a BCI pipeline with multiple session meditation/ non-meditation EEG data, we could successfully classify a new session for the same person. This creates an opportunity for initiating research developing algorithms to support a person to progress in meditation expertise, especially when such progress usually comes with many sessions of meditation practice. Future studies need to be done to improve the classification accuracies, to achieve multiple session inter-subject classification and, to identify characteristics to monitor how meditation EEG changes (progresses) over time.

Data availability

The dataset DOI is https://doi.org/10.18112/openneuro.ds003816.v1.0.1 and is available at https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds003816/versions/1.0.1.

References

Kora P, Meenakshi K, Swaraja K, Rajani A, Raju MS (2021) EEG based interpretation of human brain activity during yoga and meditation using machine learning: a systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract 43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101329

Thomas JW, Cohen M (2014) A methodological review of meditation research. Front Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00074. 5:

Chiesa A, Calati R, Serretti A (2011) Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clin Psychol Rev 31:449–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.11.003

Ferrarelli F, Smith R, Dentico D, Riedner BA, Zennig C, Benca RM, Lutz A, Davidson RJ, Tononi G (2013) Experienced mindfulness meditators exhibit higher parietal-occipital EEG Gamma Activity during NREM Sleep. PLoS ONE 8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073417

Hankey A, Shetkar R (2016) Self-transcending meditation is good for mental health: why this should be the case. Int Rev Psychiatry 28:236–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2016.1191449

Bostock S, Crosswell AD, Prather AA, Steptoe A (2019) Mindfulness on-the-go: effects of a mindfulness meditation app on work stress and well-being. J Occup Health Psychol 24:127–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000118

Huberty J, Green J, Glissmann C, Larkey L, Puzia M, Lee C (2019) Efficacy of the mindfulness meditation mobile app calm to reduce stress among college students: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 21. https://doi.org/10.2196/14273

Qu C, Sas C, Daudén Roquet C, Doherty G (2020) Functionality of top-rated mobile apps for Depression: systematic search and evaluation. JMIR Ment Health 7:e15321. https://doi.org/10.2196/15321

Davis DM, Hayes JA (2011) What are the benefits of mindfulness? A practice review of psychotherapy-related research. Psychotherapy 48:198–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022062

Lutz A, Slagter HA, Dunne JD, Davidson RJ (2008) Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends Cogn Sci 12:163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005

Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H (2004) Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: a meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 57:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7

Cahn BR, Polich J (2006) Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies. Psychol Bull 132:180–211. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.180

Ramli N, Kuok SS, Tan LK, Tan YQ, Tan LF, Goh KJ, Kadir KAA, Seow PC, Goh SY (2019) Effect of mindfulness meditation on brain-computer interface: fMRI perspective. Neurol Asia 24:343–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2013.10.010

Magan D, Yadav RK, Bal CS, Mathur R, Pandey RM (2019) Brain plasticity and neurophysiological correlates of meditation in long-term meditators: a fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography study based on an innovative methodology. J Altern Complement Med 25:1172–1182. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2019.0167

Izzetoglu M, Shewokis PA, Tsai K, Dantoin P, Sparango K, Min K (2020) Short-term effects of meditation on sustained attention as measured by fNIRS. Brain Sci 10:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10090608

Nasrolahzadeh M, Mohammadpoory Z, Haddadnia J (2019) Analysis of heart rate signals during meditation using visibility graph complexity. Cogn Neurodyn 13:45–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11571-018-9501-5

Kamei T, Toriumi Y, Kimura H, Kumano H, Ohno S, Kimura K (2000) Decrease in serum cortisol during yoga exercise is correlated with alpha wave activation. Percept Mot Skills 90:1027–1032. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.2000.90.3.1027

Lau MA, Bishop SR, Segal ZV (2010) The Toronto Mindfulness Scale: Development and Validation. J Clin Psychol 66:430–441. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp

Davis KM, Lau MA, Cairns DR (2009) Development and preliminary validation of a trait version of the toronto mindfulness scale. J Cogn Psychother 23:185–195. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.23.3.185

Roquet CD, Sas C (2018) Evaluating mindfulness meditation apps. Conf Hum Factors Comput Syst - Proc 2018–April. https://doi.org/10.1145/3170427.3188616

Flett JAM, Hayne H, Riordan BC, Thompson LM, Conner TS (2019) Mobile Mindfulness Meditation: a Randomised Controlled Trial of the Effect of Two Popular Apps on Mental Health. Mindfulness (N Y) 10:863–876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1050-9

Crivelli D, Fronda G, Venturella I, Balconi M (2019) Supporting Mindfulness practices with Brain-Sensing devices. Cogn Electrophysiological Evidences Mindfulness (N Y) 10:301–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0975-3

Brandmeyer T, Delorme A (2013) Meditation and neurofeedback. Front Psychol 4:3–5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00688

Brandmeyer T, Delorme A, Wahbeh H (2019) The neuroscience of meditation: classification, phenomenology, correlates, and mechanisms. Prog Brain Res 244:1–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2018.10.020

Fingelkurts AA, Fingelkurts AA, Kallio-Tamminen T (2015) EEG-guided meditation: a personalized approach. J Physiol Paris 109:180–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphysparis.2015.03.001

Sharma H, Raj R, Juneja M (2019) EEG signal based classification before and after combined yoga and Sudarshan Kriya. Neurosci Lett 707:134300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134300

Liyanagedera ND, Hussain AA, Singh A, Lal S, Kempton H, Guesgen HW (2023) Common spatial pattern for classification of loving kindness meditation EEG for single and multiple sessions. Brain Inf 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40708-023-00204-9

Collura TF, Guan J, Tarrant J, Bailey J, Starr F (2010) EEG biofeedback case studies using live Z-score training and a normative database. J Neurother 14:22–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10874200903543963

Hosseini MP, Hosseini A, Ahi K (2021) A review on machine learning for EEG Signal Processing in Bioengineering. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng 14:204–218. https://doi.org/10.1109/RBME.2020.2969915

Sharma H, Raj R, Juneja M (2022) An empirical comparison of machine learning algorithms for the classification of brain signals to assess the impact of combined yoga and Sudarshan Kriya. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 25:721–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/10255842.2021.1975682

Qiu L, Zhong Y, He Z, Pan J (2022) Improved classification performance of EEG-fNIRS multimodal brain-computer interface based on multi-domain features and multi-level progressive learning. Front Hum Neurosci 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.973959