Abstract

Background

Central Himalayan forested catchments provide fresh water supply and innumerable ecosystem services to millions of people. Hence, the understanding of linkages between forests and water is very crucial for availability and quality of water at catchment scale. Therefore, the present study aims to understand the hydrological response of two forested catchments (namely, Arnigad and Bansigad) in the Central Himalayan Region.

Methods

Three-years’ data (March, 2008 to February, 2011) were collected from meteorological and hydrological stations in Arnigad and Bansigad catchments. The present paper describes the mean hydrological response of these forested catchments investigated through detailed field investigation.

Results

The annual hyetograph analysis revealed that the rainfall at both the catchments was highly seasonal, and wet-period (June–September) plays a key role in catchment functioning. Exceedance of rainfall threshold of ~ 200 mm (~ 10% of annual rainfall) significantly increased streamflow generation in both catchments. In Arnigad, the stream was perennial with a mean baseflow of ~ 83 mm per month (~ 6% of annual baseflow) whereas, Bansigad had greater seasonality due to lack of streamflow during the pre-wet-period (March–May). Separation of hydrographs in Arnigad and Bansigad catchments i.e. stormflow (6% and 31%, respectively) and baseflow (50% and 32%, respectively) helped to understand the probability of flooding during wet-period and drought during dry-period. The forest ecosystem in Arnigad displayed healthier hydrological functioning in terms of reduced stormflow (82%), and enhanced baseflow (52%), soil moisture (13%), steady infiltration rate (22%) and lag time (~ 15 min) relative to Bansigad. These enhanced values indicated soil capability to store water in the forested catchment (Arnigad) and helped to understand the volume of water (discharge) that was available during dry-period. The lower denudation rate at Arnigad by 41% resulted in decreased suspended sediment (18%) and bed load (75%) compared to Bansigad. Further, the enhanced dissolved solids in the Arnigad stream resulted from the higher organic matter generated in the forest floor.

Conclusion

This study shows that rainfall during the wet-period was the main driver of hydrological functioning, whereas, forests provided substantial services by regulating water balance, soil moisture and sediment budget through different mechanisms of forest components at catchment-scale in the Central Himalayan Region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Catchments, as environmental systems, are characteristically complex and heterogeneous (Kirchner 2016), consisting of wide range of processes (natural/anthropogenic) which may function simultaneously, affecting spatial and temporal variability of the system (Zabaleta and Antiguedad 2013). This is particularly evident for mountain headwater catchments where interactions between geology, geomorphology, vegetation and harsh topography coupled with climatic forcing and multiple water inputs beyond rainfall (spring water, meltwater from snowpack, glaciers and permafrost), makes the hydrological response highly complex (Bolch et al. 2019; Scott et al. 2019). Understanding those processes is crucial in order to manage runoff (qualitatively and quantitatively), particularly when climate or landuse are changing (Naef et al. 2002; Negley and Eshleman 2006; Stewart and Fahey 2010). The change of landuse especially forest loss or forest degradation interrupts the hydrologic cycle, disturbing the food chain and habitat (Thompson et al. 2011; Jones 2013), which in turn leads to serious damage in functioning of the ecosystem (Bond et al. 2008; Blumenfeld et al. 2009; Wei and Zhang 2010; Brandon 2014; Pereira et al. 2014; Poirier and Nguyen 2017).

Substantial advancements have been made in forest hydrological research all over the globe; nevertheless, studies in the Himalayas are in their infancy (Qazi et al. 2020). Many headwater catchments in the Central Himalayan Region (CHR) in India are covered with dense forests (Tiyagi et al. 2014), which provide numerous ecosystem services to millions of people living in this region (Tiwari et al. 2017). However, these services have not gained much attention in national economic decision-making (Pandey 2012). Studies (Qazi et al. 2012; Tiyagi et al. 2014; Chauhan et al. 2017; Qazi et al. 2017; Qazi and Rai 2018) suggest that forests play a significant role in hydrological functioning of catchments in the CHR. Unfortunately, these forests are under severe stress due to dam construction, deforestation, overgrazing, tunneling, and other anthropogenic activities as well as climate change (Chaturvedi et al. 2011; Gopalakrishnan et al. 2011; Tiwari et al. 2017), disrupting hydrological services at local or catchment scale in the CHR. Further, long term field-based data, which is the key for forest and water managers to understand and predict the spatial and temporal variability of hydrology, is also scarce in this region.

The present study aims to contribute to a better understanding of the hydrological functioning of forested catchments in the CHR, India, by comparing dry and wet-period variations of hydrological processes over a 3-year period for two forested catchments: dense oak forest and a degraded oak forest. In the present study, long term field-based data has been used in order to understand (i) how forests offer services to regulate hydrological processes, specifically streamflow, soil moisture and sediments; (ii) how spatial and temporal variability affects hydrological functioning at catchment-scale in the CHR. The hydrological response of forested watersheds was studied for three consecutive years (March, 2008 to February, 2011) and the paper displays the average hydrological scenario for these catchments. Such understanding is necessary to improve our ability to manage multiple water resources at catchment-scale, and to meet the needs of local people without adversely affecting the environment.

Description of study area

Morphometric characteristics of catchments

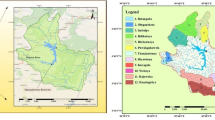

Two small neighboring headwater catchments, i.e. the dense-forested catchment, Arnigad (285.7 ha; 30°27′ N, 78°5.5′ E) and the degraded-forested catchment, Bansigad (190.5 ha; 30°27′ N, 78°2.5′ E) in Mussoorie area, CHR (Fig. 1) were selected for the present study. Both catchments are located near (∼1.5 km areal distance) each other, have similar mean slopes (21.86°, Arnigad and 23.61°, Bansigad) and aspects (south-facing). The morphometric characteristics of both the catchments are also almost same (Table 1). Both the catchments are drained by second-order streams at the gauging site. The Arnigad subsidizes to the Rispana River (Ganga River Basin) whereas the Bansigad subsidizes to the Tones River (Yamuna River Basin, a tributary of Ganga River). Both catchments are protected under private ownership and management and no forest cover change was noticed during the study period.

Characteristics of vegetation

Arnigad and Bansigad catchments are dominated by Oak forest (Quercus leucotrichofora), having 237 and 124 ha of forest canopy cover (FCC), respectively (Fig. 1). The image for FCC (Linear Imaging Self Scanning Sensor, LISS-III satellite imagery, resolution 23.5 m) was taken from the Bhuvan website in 2008. Landuse/Land cover maps were developed from LISS-III imagery with the help of software (ERDAS Imagine 9.2). Tree density (TD) was measured by laying out the quadrates. Six representative sites (three in each watershed) were selected and five quadrates (10 m × 10 m) were laid down at each site. TD was higher in Arnigad catchment (487 ± 210 trees·ha− 1) as compared to Bansigad catchment (380 ± 194 trees·ha− 1). Diameter at breast height (DBH) was measured at each quadrate (at 1.73 m height) by using a tape measure. Average DBH was also larger at Arnigad (30.57 ± 8 cm) as compared to Bansigad (16 ± 7 cm). At Bansigad, out of 15 quadrates selected at three sites, the species composition was found to be 64% Oak, 17% Cupressus, and 19% others (which includes Bhimal, Parang, Kail, Khadki, Terbara, Jungli Nashpati), whereas at Arnigad, the species composition was 98% Oak and 2% others. The percentage differences of FCC, TD and DBH were calculated as ((A–B)·B− 1 × 100), where ‘A’ and ‘B’ represents Arnigad and Bansigad, respectively. It was found that FCC (91%), TD (28%) and DBH (98%) were higher at Arnigad as compared to Bansigad.

Climatology of the region

The climate of the study area was considered to be Cfa (Warm Oceanic climate/Humid subtropical climate) according to the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Mean annual rainfall was 2243 mm (1869–2010), most of which (80%) occurred during summer months (June to September) while 20% occurred during the winter months (Sharma et al. 2012). Maximum annual temperature was 28 °C and was observed in May, while minimum annual temperature was 6 °C and was observed in January (Sharma et al. 2012).

Methodology

Rainfall measurements

In order to measure rainfall, two types of rain gauges were used: a tipping bucket rain gauge (Rainwise, USA; 325 cm2 orifice, 0.25 mm per tip) and manual rain gauge (RK Engineering, India; 2000 cm2 orifice). The data from the tipping bucket rain gauges were cross-checked with the manual rain gauges (1-day temporal resolution) installed at the same measurement site. Both types of rain gauges were installed at two elevations (at ~ 1700 m and ~ 1900 m a.s.l.) in each catchment. There was no significant difference between the rainfall sums measured at the two stations in both the catchments. Apparently, the elevation difference between the two stations was inadequate, while, the slope, aspect and other morphometric characteristics which are vital factors affecting rainfall in CHR (Katiyar and Striffler 1984), were almost similar in both the catchments (Table 1).

Discharge measurements

A rectangular weir with a sharp-crested 120° V-notch was constructed for better gauging of low flows at both the catchments (Fig. 2). The width of the weir was 4.8 and 6.6 m at Arnigad and Bansigad, respectively. Water levels were measured using Automatic Water Level Recorder (AWLR) at 15-min intervals and converted into discharge. AWLR (Virtual make) is an Optical Shaft Encoder based instrument with float and pulley (Range: 0 to 5 m, Resolution: 1 mm and Accuracy: +/− 5 mm). Hydrograph separation was done with the help of physically based filter technique given by Furey and Gupta (2001). Furthermore, baseflow recessions were examined by using the method described by De Zeeuw (1973). The dry period (1st Oct. 2009 to 28th Feb. 2010) was selected for recession period because of clear visibility of the end of direct flow or starting point of baseflow.

Soil moisture measurements

In the present study, WATERMARK Sensors were used for the measurement of soil moisture. WATERMARK Sensor (IRROMETER, California) is a granular matrix sensor (Range: 0–200 Centibar). Three sites were selected at both the catchments for measuring the soil potential (Fig. 1) and sensors were installed at 25, 50 and 80 cm depths, at each site. The soil matric potentials from all the sensors were monitored fortnightly throughout the study period. During sensor installation, undisturbed soil samples were collected from all three depths at each site and soil moisture retention curves were developed with the help of pressure plate apparatus for 0.1, 0.33, 0.5, 0.7, 1, 3, 5, 7, 10 and 15 bar pressure. The soil moisture retention curves were used to convert the observed soil matric potential values into equivalent values of volumetric soil moisture content (SM). SM values held at 0.33 bar were considered as field capacity (FC) of catchments (Thompson 1999).

Annual water budget

The hydrologic cycle for both catchments was calculated mathematically by the water budget equation (Edwards et al. 2015):

where Qt is total streamflow, P is rainfall, ET is evapotranspiration, ΔS is the change in soil moisture storage (i.e., water present in soil), and ΔG is the change in groundwater storage. The corresponding changes in soil moisture (ΔS) and groundwater (ΔG) storage between water years were derived by associated difference in volumes of soil moisture and baseflow at the start and finish of each water year. Combining the Qt, P, ΔS and ΔG, gave apparent annual evapotranspiration losses (ET) for the catchments. Average values of three respective water years were used in this study.

Sediment measurements

The water samples were collected in 1-l bottles at the gauging sites on the mainstream (Fig. 2). The collected water samples were analyzed by following a grab sample method (International Atomic Energy Agency 2005). Whatman-72 filter papers were used for the separation of suspended sediments from the water samples. During the wet-period (June–September), the sampling was done three times a day: 8:00 AM, 2:00 PM and 8:00 PM whereas during the dry-period (October–May), sampling frequency was daily (8:00 AM). The suspended sediment concentration (mg·L–l) was converted into suspended sediment load, suspended sediment load (SSL) (t·km− 2) by using conversion factor, discharge and area of the catchments.

Total dissolved solids were measured using TDS meter. During wet-period, the frequency of TDS measurement was on daily basis, however, during rest of the year the frequency was once every fortnight as there was no significant change in TDS. The concentration of TDS (ppm) was converted into total dissolved load, Total dissolved load (TDL) (t·km− 2) using a conversion factor based on the discharge and area of the catchments.

Bed load (BL) was estimated following Hedrick et al. (2013). The pond like structure (6 m × 4.8 m for Arnigad and 12 m × 6.62 m for Bansigad) at gauging sites were constructed so that sediments could accumulate within them. It was assumed that most of the BL material got deposited in these structures. The volumes of BL were derived by measuring various depths/heights of deposited material at these structures. A bulk density of 1.4 t·m− 3 (BBMB, Bhakra Beas Management Board 1997) was used for the conversion of these volumes into mass. The measurement of accumulated BL followed by mechanical cleaning was carried out every month; however, during wet-period, the frequency of measurements followed by cleaning was 5–6 times in a month to avoid flushing of bed material during peak events. Total sediment budget is the sum of SSL, TDL and BL.

In the Himalayan region, high relief and high intensity monsoonal rainfall provides favorable conditions for mass wasting (Korup and Weidinger 2011). Long-term mass wastage or denudation rates were estimated following Gregory and Walling 1973:

Denudation (D) rates are expressed in mm·yr− 1, which is equivalent to m3·km− 2·yr− 1, total load is in tonnes·yr− 1, area is in km2 and the average density of rock or soil was considered to be 2.67 g·cm− 3 (Lupker et al. 2012; Chauhan et al. 2017).

Infiltration measurements

Eight infiltration tests were conducted (4 in each catchment) with the help of double-ring infiltrometers in March 2010 when the soil profile had dried out. The inner ring was 30 cm in diameter and 15 cm high, while the outer ring was 60 cm in diameter and 15 cm high, respectively.

Soil properties

To evaluate the soil properties, soil samples were collected from predetermined depths of 0–15, 15–30, 30–60, 60–90 and 90–120 cm by using an Auger. All soil samples were collected at six representative sites (three in each catchment) (Fig. 1). The three sites spanned a gradient from ridgeline to catchment outlet (1650–2230 m a.s.l. for Arnigad and 1620–2170 m a.s.l. for Bansigad). The soil samples were analyzed for organic matter (Walkley and Black 1934), texture and porosity (Black 1965).

Statistical analysis

T-tests were performed in order to calculate statistical differences. The percentage differences of all parameters between Arnigad and Bansigad were calculated as ((A–B)·B− 1 × 100), where ‘A’ and ‘B’ represents Arnigad and Bansigad, respectively.

Lag time analysis

In order to understand the response of catchments after rainfall, around 40 hydrographs (during wet-period) were analyzed to determine lag time between rainfall and discharge. The lag time was analyzed by calculating the delay between the maximum rainfall amount and the peak discharge. Out of 40 hydrographs, 3 hydrographs along with corresponding hyetographs were analyzed in detail in order to calculate the volume of water/discharge (m3·s− 1) released from catchments after rainfall events.

Results

Temporal variations of rainfall

Wet-period (June to September), was the core season when hydrological processes in catchments were the most active; and were inactive during dry-period (October to May). The wet-period played a substantial role in the catchments’ functioning by providing ~ 78% (for each catchment) of the annual rainfall of 2922 mm (Fig. 3). Patterns and amount of monthly rainfall observed (during 3-years) over both the catchments were quite similar and did not differ significantly (p < 0.05) from each other. Minimum and maximum values of mean monthly rainfall ranged from 11 to 909 mm in both catchments. Winter rainfall in the form of snow was negligible at either location. May and June were transition months/stage between dry and wet periods. During this transition period, rainfall exceeds thresholds (~ 10% of annual rainfall) and hyetograph starts rising. July, August and September were the peak months whereas October, the falling limb of the hyetograph (Fig. 4a).

Streamflow behavior

Temporal variations of Qt for both the catchments clearly reflect the seasonal patterns and are in coherence with dry and wet-periods (Fig. 3). Generally, during last week of June, Qt of Arnigad and Bansigad reached values of 48 and 14 mm (~ 3% and 1% of annual flow) and after that Qt started rising instantly (Fig. 4a). Bansigad had greater seasonality due to lack of flow during the pre-wet-period (March–May), whereas discharge was maintained year-round in Arnigad stream. Seasonal (wet-period) and annual Qt in Arnigad were lower by ~ 34% and 13%, respectively relative to Bansigad.

Mean stormflow production in the Arnigad was modest with the sum of 167 mm·yr− 1 (10% of annual Qt), 90% of which occurred during the main wet-period. Conversely, stormflow was much higher for the degraded catchment amounting to 914 mm·yr− 1 (49% of annual Qt), with 78% contribution from the wet-period. In addition, stormflows during post-wet-period (October–November) were important at Bansigad, contributing 18% of the annual totals whereas it was just 2% at Arnigad. Annually, stormflow at Arnigad was lower by ~ 82% as compared to Bansigad.

Mean annual baseflow at Arnigad and Bansigad was 1446 and 949 mm·yr− 1 (90% and 51% of annual flow) whereas seasonal (wet-period) contribution was 784 mm (54%) and 712 mm (75%), respectively. Baseflow was ~ 52% (annually) higher at Arnigad and became an important contributor for making the stream perennial unlike the ephemeral Bansigad. The contribution of stormflow and baseflow significantly varied from January to December and its temporal variation is presented in Fig. 4b. Recession rates of the baseflow for the Bansigad catchment during the dry-period were much faster, with a reservoir response factor of ~ 0.028 per day, whereas it was ~ 0.0083 per day for the densely forested Arnigad (Fig. 5). The exponential recession curve of the outflow from groundwater reservoirs in either catchment (Fig. 5) did not deviate from linear reservoir theory, indicating negligible leakage losses and hence letting direct comparison between the two catchments. The annual water budgets (Fig. 6) for the studied catchments displayed that though there was no significant difference in annual P, however, there was significant difference in annual Qt, ΔS, ΔG storage and ET, respectively, between the catchments. On an average, 43% (Arnigad) and 36% (Bansigad) of P was lost as ET, which means only 55% and 64% of P respectively was available as Qt at Arnigad and Bansigad catchments (Fig. 6).

Soil moisture behavior

Temporal behavior of SM at different depths is presented in Fig. 7a. Mean annual volumetric SM at Arnigad and Bansigad was higher (41% and 39%) during wet-period, however it was lower (28% and 24%) during dry-period. This showed that Arnigad was having 4% (wet-period) and 16% (dry-period) higher SM as compared to Bansigad, respectively. At annual scale (at Arnigad) mean SM was lower by 4% at upper surface and higher by 13% and 31% at deeper layers as compared to Bansigad (Fig. 7b). At Arnigad, SM at 80-cm depth held more SM than at 50 cm.

Infiltration rate

Variations of initial and steady infiltration rates in Bansigad were smaller (50–64 cm·hr.− 1 and 13–32 cm·hr.− 1 respectively) as compared to Arnigad (20–134 cm·hr.− 1 and 8–30 cm·hr.− 1 respectively). Initial infiltration rate was lower by 29%, while steady infiltration rate was higher by 21% at Arnigad relative to Bansigad (Table 2).

Characteristics of soil

Soil texture analysis gave higher amount of silt and clay (13% and 23%) fractions at Arnigad as compared to Bansigad. Organic matter (OM) and porosity were also higher (by 35% and 8% respectively) at Arnigad as compared to Bansigad. The results revealed that soil texture was better in the forested catchment (Arnigad) as compared to degraded forest (Bansigad) catchment. Figure 8 shows the variation of soil properties with depth.

Sediment budget

Temporal variations of different types of constituents in Qt including SSL, TDL and BL are presented in Fig. 9a, b and c. A very large temporal variation (monthly) in SSL was observed ranging 0.28–738 and 0–1265 t·km− 2 at Arnigad and Bansigad, respectively. Arnigad experienced the lowest SSL from March to May, whereas the stream remained dry during these months at Bansigad. The wet-period contributed 95% (of the annual load) of SSL, which substantially affected annual sediment behavior at both the catchments. The average annual budget of SSL was 1112 t·km− 2 (Arnigad) and 2143 t·km− 2 (Bansigad) respectively, almost making suspended sediment budget of Bansigad double that of Arnigad (Fig. 9d).

Mean monthly TDL of Arnigad ranged between 21 and 153 t·km− 2, while that of Bansigad ranged between 0.2 and 177 t·km− 2. The TDL was consistently found to be higher than SSL during drier months. Mean annual yield of TDL at Arnigad and Bansigad was 698 and 488 t·km− 2, respectively (Fig. 9d).

The volume of BL (monthly) flowing in the Arnigad stream was in the range of 0.03–17.28 m3, whereas it was 74.64 m3 at Bansigad where March-mid June, no bedload material was observed. Mean monthly BL accumulation ranged from 0.09 to 4.92 t·km− 2 and from 0.5 to 37.5 t·km− 2 at Arnigad and Bansigad, respectively. The average bed material deposited annually was 19 t·km− 2 (Arnigad) and 114 t·km− 2 (Bansigad), respectively, which indicated that BL accumulation was higher (6 fold) at Bansigad relative to Arnigad (Fig. 9d).

Mass wastage has been considered the dominant erosional process on hillslopes and the denudation rate was calculated for both the catchments. The average denudation rates were 0.68 mm·yr− 1 (Arnigad) and 1.02 mm·yr− 1 (Bansigad), respectively, indicating that Bansigad losses its mass at about 1.5 times higher rates than Arnigad.

Discussion

Forest cover impacts on streamflow regulation

Studies concerning the impact of forest cover changes on the magnitude of Qt in Himalayan region are rare (Sharma et al. 2007; Ashraf 2013; Tiyagi et al. 2014); however, studies related to components of Qt (baseflow and stormflow) are even more rare in the region. During the study period, the annual cycle of rainfall represented both dry and wet-period (Fig. 3), thus allowing study of baseflow and stormflow conditions of the catchments. In the same line, Qt of the catchments also showed distinctive behavior during dry and wet-periods (Fig. 3), due to highly seasonal rainfall in the CHR (Banerjee et al. 2020). Dry-period represented the greater part of annual hyetograph, however, wet-period represented the main driver for the Qt generation. The 2nd order polynomial relationship between rainfall and Qt (Fig. 10a) allowed the identification of rainfall threshold (~ 200 mm), and when this threshold exceeded, Qt generation increased significantly in both the catchments (Fig. 10a). The same threshold value (~ 200 mm), which accounted for ~ 10% of annual rainfall was also observed in Fig. 4b. This rainfall threshold mostly occurred during mid-June, and before June, the low magnitude rainfall (below 200 mm per month) potentially catered to several hydrological processes e.g., initial infiltration, SM, ground water stress and ET (Tarboton 2003) in both catchments. The rainfall threshold values of both the catchments can be helpful to predict Qt generation (Kirkby et al. 2005; Gioia et al. 2008; Kampf et al. 2018), which is vital for not only sustaining streams, but also regulating numerous ecological processes (Poff et al. 1997; Doll et al. 2015). Separation of hydrographs (Arnigad and Bansigad) into stormflow (6% and 31%) and baseflow (50% and 32%) (Fig. 4a and b), vastly improves our understanding of Qt regulation at catchment-scale and surely will be helpful for water resource management (Nepal et al. 2014) in the CHR.

Arnigad catchment showed lower annual Qt and higher ET compared to the Bansigad catchment (Fig. 6). Despite having higher ET, Arnigad’s annual baseflow component was higher by ~ 52% relative to Bansigad. This was because of forest floor components (i.e. litter layer, or the accumulation of leaves, twigs, and other vegetative debris), which increased OM, porosity, clay and silt content in soil, and resulted in better soil formation in Arnigad catchment (Fig. 8), further leading to higher SM retention (O'Geen 2013) relative to Bansigad. Furthermore, these forest floor components might also act as effective shade barrier on the soil surface and reduce the rate of air exchange between the soil and the atmosphere, resulting in SM retention (Edwards et al. 2015). Besides, higher TD and DBH at Arnigad, indicated deep rooting which facilitate rapid drainage to deeper layers via macropores (Noguchi et al. 1997; Bargués Tobella et al. 2014). Their dominance (in Arnigad) in controlling SM retention was critical to retaining moisture within the soil. Rainfall moving in macropores resupply to groundwater, known as groundwater recharge. Groundwater released water with a slow recession rate (Fig. 5) subsequently during the dry-period to Qt through contributions known as baseflow, which makes the stream perennial (at Arnigad) with a mean baseflow of ~ 83 mm (~ 6% of annual baseflow). Whereas, mean baseflow of only ~ 30 mm (~ 3% of annual baseflow) was available till February month which was not sufficient to make Bansigad stream sustainable during few months (March to May) of dry-period (Fig. 4a). The study indicated that both streams were dependent on rainfall for Qt generation, but the rainfall at Arnigad sustained baseflow during dry-period through different mechanism of forest components. Furthermore, the baseflow and stormflow at Bansigad showed larger variations as compared to Arnigad (Fig. 4b), the large variation was due to the faster recession rates at Bansigad catchment during the dry-period, with reaction/response factors of 0.028 day− 1 compared to Arnigad catchment (0.0083 day− 1). The faster recession rate at Bansigad, diminished Qt completely during dry-period, however, for dense forest (Arnigad) the baseflow was higher by ~ 52% annually, helping to maintain Qt year round. Hence, the higher proportion of the stormflow at Bansigad, indicated higher probability of water resource problems such as flooding in the wet-period and drought in the dry-period. Baseflow recessions are important for the management of both ground water and surface water resources during dry-period (Miller et al. 1953).

The 40 selected hydrographs revealed the response of catchments after rainfall, showing that the lag time generally increased for small and early wet-period events and decreased for larger events. Lag time of both the catchments ranged between 0:15 to 0:45 h. If the time gap between two consecutive rainfalls were larger, lag time of hydrographs also became larger and during wet-period when the catchments were fully saturated with SM, a few rainfall events immediately become runoff/stream discharge. Among 40 hydrographs, it was observed that only three rainfall events started and finished at same time period (29.07.08 to 31.07.08) at both the catchments. Furthermore, these events occurred in July, peak of the monsoon, and it is obvious that the soil was fully saturated. Therefore, this time period gave an opportunity to compare both volume of water (discharge) and lag time between catchments. Hence, these 3-hydrographs along with corresponding hyetographs for the same time period from 29.07.08 to 31.07.08 and at same interval (15-min interval) were analyzed in detail (Fig. 11). There was no significant difference (p = 0.05) in rainfall events between Arnigad (36–109 mm) and Bansigad (47–118 mm), however, there was significant difference in discharge between Arnigad (0.60–0.81 m3·s− 1) and Bansigad (0.81–1.32 m3·s− 1), respectively. Further, lag time of these three events were: 0:45, 0:45 and 0:30 h (Arnigad) and 0:30, 0:30 and 0:15 h (Bansigad), respectively (Fig. 11). The shape of the hydrographs varied with each individual rainfall event. The analysis revealed that during wet-period, Arnigad releases lower volume of water, which took on average additional 15 min (compared to Bansigad) to reach the gauging site. This behaviour of hydrographs (in Arnigad) may possibly be to the combined effect of (i) slow recession rate of baseflow for Arnigad (Fig. 5), (ii) higher potential of forest soil to store water in Arnigad (Fig. 7) and (iii) higher infiltration rate (Table 2). Therefore, the volume of water that was stored in Arnigad during rainfall events and the longer lag time helped in releasing water during recession, and maintaining the baseflow during dry-period, which are important ecosystem functions of the catchment. Thus, the study indicates that the forest cover in Arnigad showed significant and positive relationship with both baseflow and stormflow. These relationships can be applied to other catchments to effectively manage current and future land use and water resource problems in CHR.

The Non-linear relationships between Qt and SM (Fig. 10b) allowed the identification of threshold value (~ 35%) of SM. When the SM threshold was exceeded, baseflow got activated, increased significantly and became a major contributor to stormflow. A clear threshold (~ 35%) between SM and Qt, revealed the importance of initial moisture conditions, which determined the extent of saturation and controlled the Qt production for the entire catchment (Penna et al. 2010). The threshold value (0.35) was very close to mean field capacity (FC), which was 0.35 and 0.33 for Arnigad and Bansigad, respectively. This further confirms that the activation of Qt occurred only after soil attained threshold SM value of 35%. Other studies observed SM threshold at 45% (Penna et al. 2011; Song and Wang 2019), 26% (Farrick and Branfireun 2014) and 23% (James and Roulet 2007) highlighting the importance of initial moisture conditions. The difference in threshold values might be due to difference in topography, climate, land use characteristics, soil characteristics and sampling designs. Results of the present study showed that two factors: SM and P were responsible for Qt activation and generation. Figure 4a and b, indicates that June was the transition period, when hydrological functioning (Qt activation and generation) of the catchments began to activate and October was again a transition period when hydrological functioning began to deactivate. Non-linear behavior is common in hydrological systems (Zuecco et al. 2018) and these thresholds can be used as a classification tool to better conceptualize runoff response behavior under a range of weather conditions (Ali et al. 2013, 2015).

OM showed direct positive linear relationship with tree density (Fig. 12a). Higher tree density means higher OM in soil, which helps in binding soil particles together into stable aggregates, increasing porosity (Zuazo and Pleguezuelo 2008; Tobella et al. 2014), and finally leading to higher infiltration (Fig. 12b). Both SM and vegetation are closely linked; SM positively influences vegetation growth (Wang et al. 2007), whereas vegetation displays complex relationship with SM. More vegetation either conserve more water, causing retention of SM or consumption of water itself, causing the depletion of SM (Pielke et al. 1998; Wang et al. 2006). Hence, more vegetation may correspond either to increase (Bounoua et al. 2000; Buermann et al. 2001) or to decrease of SM (Pielke et al. 1998; Wang et al. 2006). The present study supports the strong interlinkages of forests/vegetation with SM; interestingly SM also showed positive and direct impact on infiltration rate (Fig. 12c). Further work is required in future to understand these relationships at different spatial and temporal scale in CHR. However, the results from the present study will be of help to farmers, land managers and policy developers in conserving and sustainably developing forest, soil and water resources in this region.

Soil moisture variation at different soil profiles

Temporal variations of SM at different depths under different forest covers are shown in Fig. 7a. It was observed that SM at all the profiles was responsive to rainfall events, though a few events might have been missed as the parameters were measured at fortnightly intervals. The annual cycle of both rainfall and SM follows the same path with unimodal variation (Fig. 7a), and SM reached its maximum during wet-period, when ~ 78% of annual rainfall occurred. Furthermore, SM at all soil layers were below FC during dry-period, whereas, it was above FC during wet-period at both catchments (Fig. 7a). Such behavior indicated that SM was mainly regulated by P (Varikoden and Ravadekar 2018). It is observed from Fig. 7a and b, that during the wet-period, the surface layers at both the catchments were wetter than the deeper layers. This was because low intensity P’s were likely to be retained at the soil surface layer (Li et al. 2016). The variability in SM of the surface layer was even more distinct in Bansigad catchment, showing low interception losses due to degraded forest, resulting in a large proportion of rainfall reaching the ground surface (Venkatraman and Ashwath 2016; Liu et al. 2018) and therefore, the Bansigad catchment showed higher (4%, annually) moisture regimes in surface layer than that for Arnigad (Fig. 7b). For Arnigad catchment, SM was maximum at a deeper layer (80 cm) than at 50-cm depth. This was possibly due to lower rate of water movement to the next soil layer or may be influenced by lateral flow (within the soil layer) from the upslope due to change in the saturated hydraulic conductivity properties (Venkatesh et al. 2011). Many studies (Gutiérrez-Jurado et al. 2007; Toro-Guerrero et al. 2018) from hillslopes or areas having steep slopes supported active response of lateral flow to deeper soil layers, thus efficiently bypassing the shallower soils, which are more exposed to ET. Therefore, SM in the hillslopes varies both in the vertical and lateral directions (Venkatesh et al. 2011). Annually, SM at Arnigad at 50 and 80 cm was enhanced by 13% and 31% in comparison to Bansigad (Fig. 7b). These enhanced values indicated potential for soil water storage in the forested catchment (Arnigad), and slow release of water during the subsequent dry-period, which consequently helps in regulation of sustained stream flows in the Himalayan region. This is further supported by Fig. 12, which shows that Arnigad had higher OM (21%–89%) and higher porosity (3%–11%) than Bansigad helping Arnigad to retain SM and uphold sponge characteristics (Qazi et al. 2017). The lowest values of volumetric SM (mean monthly) were recorded as 25% (Arnigad) and 21% (Bansigad), indicating low (19%) storage deficit at Bansigad relative to Arnigad. Therefore, water retention/flow regulation in dense forested catchment (Arnigad) was better in comparison to the degraded forested catchment (Bansigad). Thus, the present study suggests that forests play an important role in SM functioning at local sites (Bruijnzeel 2004) and provides hydrological services in different ways at catchment scale. However, further research work is required to understand the dynamics and transport of soil water content from shallow to deeper soil layers for potential ground water recharge.

Forest cover impacts on sediment transportation/erosion behavior

Sediment transport is a function of several interacting factors including vegetation, climate, topography, parent material, and soil. Rainfall during the monsoon was the main driver and contributed significantly in annual sediment transportation (95%) in both the studied catchments (Fig. 9a), while forests regulated sediment transport activity in these catchments through various forest components (forest cover, understory, tree roots, and woody debris). Forest cover supported in reduction (18%) of suspended sediment production at Arnigad catchment through strong root system that holds soil particles tightly and doesn’t allow natural forces (wind and water) to take away the upper-most layer of the soil. Moreover, the understory (shrubs, herbs, leaf litter etc.) at Arnigad also helped in decreasing surface erosion by reduction of kinetic energy of raindrops (Fukuyama et al. 2010; Nanko et al. 2015). On the other hand, it was found that the degraded forest along with high intensity rainfall triggered loosened material and debris (Fuller et al. 2003), leading to landslides (Struck et al. 2015), and further to higher sediment production in Bansigad stream (Tyagi et al. 2013), continuously disturbing the natural system (Mukherjee 2013) of the Bansigad catchment. The lower (75%) deposited BL material in Arnigad catchment (Fig. 9c) was because of the standing trees, felled logs and understory of dense forest, which slowed down the movement of big boulders, gravel and debris (Qazi and Rai 2018). Moreover, the strong tree root system and organic humus layer supports slope stability, decreases landslides and debris flow frequency (Imaizumi et al. 2008; Nepal et al. 2014; Goetz et al. 2015); hence BL material couldn’t reach Arnigad stream unlike Bansigad stream. Hartanto et al. (2003) and Imaizumi et al. (2019) also reports that a large amount of sediments are captured by woody debris on hillslopes. The present study proves that forest plays important roles in regulating sediment transportation and forest plantation and conservation can be considered as an important means of improving the mountain environment.

Interestingly, the concentration of dissolved material in streams of Arnigad was also enhanced by 114% (annually) as compared to Bansigad (Fig. 9b). As both the catchments were located near to each other, the rock types and their erodibility are assumed to be the same. Apparently, the landuse or forest was the only element to account for higher dissolved solids at Arnigad catchment. Large quantity of OM are generated in the forest floor at Arnigad catchment, which decompose, percolate through rain water (Krishna and Mohan 2017), and reach streams in dissolved form (Markewitz et al. 2004; Andrade et al. 2011; Costa et al. 2017). Hence, the dissolved OM concentrations affect TDS in the stream. Dry-period has significant impact on the wide range of TDS at Bansigad, because TDS becomes more concentrated with decreasing discharges (Tipper et al. 2006; Calmels et al. 2011). TDS in both the catchments was within the permissible limit according to WHO (1996) and BIS (2012).

In the Himalayan region, high relief coupled with intensive rainfall during monsoon provide favorable conditions for mass wasting (Korup and Weidinger 2011), which causes serious long-term problems affecting functioning of hydropower plants, dam and river management, environmental flows, biological diversity, reservoir siltation, landslides, etc. (Zokaib and Naser 2011; Hedrick et al. 2013; Sudhishri et al. 2014; Iwuoha et al. 2016). Reduction of annual sediment budget (Fig. 9d) and denudation rate by 41% in Arnigad compared to Bansigad further confirms the crucial role of trees and forests in preventing mass wastage, helping to sustain ecological functioning and biological diversity and reduces hazards e.g. landslides, in the long run.

Conclusion

During the study period that comprised both dry-period and wet-period, thus allowing to study baseflow and stormflow conditions of the two studied catchments. The annual hyetograph analysis revealed that the rainfall at both the catchments was highly seasonal, and wet-period plays a key role in hydrological functioning of catchments. The identification of rainfall threshold values of both the catchments (200 mm per month) can be helpful to predict Qt generation, which is vital for sustenance of streams and regulation of numerous ecological processes. The Arnigad catchment maintains its baseflow of ~ 83 mm per month (~ 6% of annual baseflow) during dry-period making the stream perennial; however, baseflow was not available at Bansigad during a few months of dry-period making the stream intermittent. The analysis revealed that both streams were dependent on rainfall for Qt generation, but the timescale over which rainfall at Arnigad can sustain baseflow was greatly enhanced relative to Bansigad.

The present study also highlighted the strong control exerted by SM on Qt. A sharp threshold (~ 35%) existed between SM and Qt, above which baseflow was activated, increased significantly and became a major contributor to stormflow. Therefore, the study estimated the threshold, responsible for Qt activation and generation, which may serve as a foundation for future studies that predict Qt response to climate and anthropogenic change in the CHR. Further, the continuous faster recession rates of baseflow, low potential of forest soil to store water (SM) and lower infiltration rates were responsible factors for the diminishing Qt during a dry-period in Bansigad catchment. The various forest components in Arnigad catchment helped in reduction (41%, relative to Bansigad) of soil denudation rate. Thus, the present study suggests that rainfall during wet-period was the main driver for controlling hydrological processes, whereas, forests provided substantial services by regulating water balance, SM and sediment budget in Arnigad catchment. Moreover, the forest also helped in maintaining soil properties and infiltration rates by adding OM to soil. Based on the findings, the paper concludes that our understanding of hydrological functioning at catchment scale advances our ability to improve water resource management in CHR and meet the needs of local people without adversely affecting the environment.

Availability of data and materials

The data set generated for the study area is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CHR:

-

Central Himalayan Region

- FC:

-

Field capacity

- FCC:

-

Forest canopy cover

- TD:

-

Tree density

- LISS:

-

The linear imaging self scanning sensor

- DBH:

-

Diameter at breast height

- AWLR:

-

Automatic water level recorder

- P:

-

Rainfall

- Q t :

-

Streamflow

- ET:

-

Evapotranspiration

- ΔS :

-

Change in soil moisture storage

- ΔG :

-

Change in groundwater storage

- SSL:

-

Suspended sediment load

- TDS:

-

Total dissolved solids

- TDL:

-

Total dissolved load

- BL:

-

Bed load

- D:

-

Denudation rates

- SM:

-

Soil moisture

- OM:

-

Organic matter

References

Ali G, Oswald CJ, Spence C, Cammeraat ELH, McGuire KJ, Meixner T, Reaney SM (2013) Towards a unified threshold-based hydrological theory: necessary components and recurring challenges. Hydrol Process 27(2):313–318

Ali G, Tetzlaf D, McDonnell JJ, Soulsby C, Carey S, Laudon H, McGuire K, Buttle J, Seibert J, Shanley J (2015) Comparison of threshold hydrologic response across northern catchments. Hydrol Process 29(16):3575–3591

Andrade TMB, Camargo PB, Silva DML, Piccolo MC, Vieria SA, Alves LF, Joly CA, Martinelli LA (2011) Dynamics of dissolved forms of carbon and inorganic nitrogen in small watersheds of the coastal Atlantic forest in Southeast Brazil. Water Air Soil Pollut 214:393–408

Ashraf A (2013) Changing hydrology of the Himalayan watershed, Chapter 9. In: Bradley P (ed) Current perspectives in contaminant hydrology and water resources sustainability. InTech, Rijeka

Banerjee A, Dimri AP, Kumar K (2020) Rainfall over the Himalayan foot-hill region: present and future. J Earth Syst Sci 129:11

Bargués Tobella A, Reese H, Almaw A, Bayala J, Malmer A, Laudon H, Ilstedt U (2014) The effect of trees on preferential flow and soil infiltrability in an agroforestry parkland in semiarid Burkina Faso. Water Resour Res 50(4):3342–3354

BBMB, Bhakra Beas Management Board (1997) Sedimentation survey report. BBMB, Bhakra Dam Circle, Nangal

BIS (2012) Drinking Water-Specification. Bureau of Indian standards, New Delhi IS 10500

Black CA (1965) Methods of soil analysis. American Society of Agronomy. Inc, Madison

Blumenfeld S, Lu C, Christophersen T, Coates D (2009) Water, wetlands and forests: a review of ecological, economic and policy linkages. CBD Technical Series No. 47. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity and Secretariat of the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, Montreal and Gland

Bolch T, Shea JM, Liu S, Azam FM, Gao Y, Gruber S, Immerzeel W, Kulkarni A, Li H, Tahir AA, Zhang G, Zhang Y (2019) Status and change of the cryosphere in the extended Hindu Kush Himalaya region. In: Wester P, Mishra A, Mukherji A, Shrestha AB (eds) The Hindu Kush Himalaya assessment: mountains, climate change, sustainability and people. Springer, Cham, pp 209–255

Bond BJ, Meinzer FC, Brooks JR (2008) How trees influence the hydrological cycle in forest ecosystems. In: Wood PJ, Hannah DM, Sadler JP (eds) Hydroecology and ecohydrology: past, present and future. Wiley, Hoboken

Bounoua L, Collatz G, Los S, Sellers P, Dazlich D, Tucker C, Randall D (2000) Sensitivity of climate to changes in NDVI. J Clim 13(13):2277–2292

Brandon K (2014) Ecosystem services from tropical forests: review of current science, CGD Working Paper 380. Center for Global Development, Washington, DC

Bruijnzeel LA (2004) Hydrological functions of tropical forests: not seeing the soil for the trees? Agric Ecosyst Environ 104(1):185–228

Buermann W, Dong J, Zeng X, Myneni RB, Dickinson RE (2001) Evaluation of the utility of satellite-based vegetation leaf area index data for climate simulations. J Clim 14:3536–3550

Calmels D, Galy A, Hovius N, Bickle M, West J, Chiang MC, Chapma H (2011) Contribution of deep groundwater to the weathering budget in a rapidly eroding mountain belt, Taiwan. Earth Planet Sci Lett 303(1–2):48–58

Chaturvedi RK, Gopalakrishnan R, Jayaraman M, Bala G, Joshi NV, Sukumar R, Ravindranath NH (2011) Impact of climate change on Indian forests: a dynamic vegetation modeling approach. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang 16(2):119–142

Chauhan P, Singh N, Chauniyal DD, Ahluwalia RS, Singhal M (2017) Differential behaviour of a Lesser Himalayan watershed in extreme P regimes. J Earth Syst Sci 126:22

Costa END, Souza JC, Pereira MA, Souza MFL, Souza WFL, Silva DML (2017) Influence of hydrological pathways on dissolved organic carbon fluxes in tropical streams. Ecol Evol 7:228-239.

De Zeeuw JW (1973) Hydrograph analysis for areas with mainly groundwater runoff. In: Kessler J, de Ridder NA (eds) Theories of field drainage and watershed runoff. International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement, Wageningen, pp 321–357

Doll P, Jiménez-Cisneros B, Oki T, Arnell NW, Benito G, Cogley JG, Jiang T, Kundzewicz ZW, Mwakalila S, Nishijima A (2015) Integrating risks of climate change into water management. Hydrol Sci J 60(1):4–13

Edwards PJ, Williard KWJ, Schoonover JE (2015) Fundamentals of watershed hydrology. J Contemp Water Res Edu 154:3–20

Farrick KK, Branfireun BA (2014) Soil water storage, rainfall and runoff relationships in a tropical dry forest catchment. Water Resour Res 50:9236–9250

Fukuyama T, Onda Y, Gomi T, Yamamoto K, Kondo N, Miyata S, Kosugi K, Mizugaki S, Tsubonuma N (2010) Quantifying the impact of forest management practice on the runoff of the surface-derived suspended sediment using fallout radionuclides. Hydrol Process 24:596–607

Fuller CW, Willet S, Hovius N, Slinegrland RL (2003) Erosion rates for Taiwan Mountain Basins: new determinations from suspended sediment records and a stochastic model of their temporal variation. J Geol 111(1):71–87

Furey PR, Gupta VK (2001) A physically-based filter for separating base flow from streamflow time series. Water Resour Res 37:2709–2722

Gioia A, Iacobellis V, Manfreda S, Fiorentino M (2008) Runoff thresholds in derived flood frequency distributions. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 12(6):1295–1307

Goetz JN, Guthrie RH, Brenning A (2015) Forest harvesting is associated with increased landslide activity during an extreme rainstorm on Vancouver Island, Canada. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 15:1311–1330

Gopalakrishnan R, Mathangi J, Bala G, Ravindranath NH (2011) Climate change and Indian forests. Curr Sci 101(3):348–355

Gregory KJ, Walling DE (1973) Drainage basin form and process: a geomorphological approach. Edward Arnold Ltd, London, p 456

Gutiérrez-Jurado HA, Vivoni ER, Istanbulluoglu E, Bras RL (2007) Ecohydrological response to a geomorphically significant flood event in a semiarid catchment with contrasting ecosystems. Geophys Res Lett 34:L24S25

Hartanto H, Prabhu R, Widayat ASE, Asdak C (2003) Factors affecting runoff and soil erosion: plot-level soil loss monitoring for assessing sustainability of forest management. Forest Ecol Manag 180(1):361–374

Hedrick LB, Anderson JT, Welsh SA, Lin LS (2013) Sedimentation in mountain streams: a review of methods of measurement. Nat Res Forum 4:92–104

Horton RE (1932) Drainage basin characteristics. Eos T Am Geophy Un 13:350–361

Horton RE (1945) Erosional development of streams and their drainage basins: hydrophysical approach to quantitative morphology. GSA Bull 56:275–370

Imaizumi F, Sidle RC, Kamei R (2008) Effects of forest harvesting on the occurrence of landslides and debris flows in steep terrain of central Japan. Earth Surf Process Landf 33:827–840

Imaizumi F, Nishii R, Ueno K, Kurobe K (2019) Forest harvesting impacts on microclimate conditions and sediment transport activities in a humid periglacial environment. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 23:155–170

International Atomic Energy Agency (2005) Fluvial sediment transport: analytical techniques for measuring sediment load. IAEA-TECDOC-1461, ISBN 92–0–107605-3, ISSN 1011–4289, Printed by the IAEA, Vienna, Austria

Iwuoha PO, Adiela PU, Nwannah CC, Okeke OC (2016) Sediment source and transport in river channels: implications for river structures. Int J Eng Sci 5(5):19–26

James AL, Roulet NT (2007) Investigating hydrologic connectivity and its association with threshold change in runoff response in a temperate forested watershed. Hydrol Process 21:3391–3408

Jones I (2013) The impact of extreme events on freshwater ecosystems. Ecological Issues. British Ecological Society

Kampf SK, Faulconer J, Shaw JR, Lefsky M, Wagenbrenner JW, Cooper DJ (2018) Rainfall thresholds for flow generation in desert ephemeral streams. Water Resour Res 54:9935–9950

Katiyar V, Striffler WD (1984) Rainfall variation in a small Himalayan watershed. Ind J Soil Water Conserv 12:57–64

Kirchner JW (2016) Aggregation in environmental systems - Part 1: Seasonal tracer cycles quantify young water fractions, but not mean transit times, in spatially heterogeneous catchments. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 20:279–297

Kirkby MJ, Bracken LJ, Shannon J (2005) The influence of rainfall distribution and morphological factors on runoff delivery from dryland catchments in SE Spain. Catena 62(2–3):136–156

Korup O, Weidinger JT (2011) Rock type, precipitation, and the steepness of Himalayan threshold hillslopes. Geol Soc Spec Publ 353(1):235–249

Krishna MP, Mohan M (2017) Litter decomposition in forest ecosystems: a review. Energ Ecol Environ 2(4):236–249

Li B, Wang L, Kaseke KF, Li L, Seely MK (2016) The impact of rainfall on soil moisture dynamics in a foggy desert. PLoS One 11(10):e0164982

Liu J, Zhang Z, Zhang M (2018) Impacts of forest structure on precipitation interception and run-off generation in a semiarid region in northern China. Hydrol Process 32:2362–2376

Lupker M, Blard HP, Lave J, Lanord CF, Leanni L, Puchol N, Charreau J, Bourles D (2012) 10Be-derived Himalayan denudation rates and sediment budgets in the Ganga basin. Earth Planet Sci Lett 333–334:146–156

Markewitz D, Davidson E, Moutinho P (2004) Nutrient loss and redistribution after clearing on a highly weathered soil in Amazonia. Ecol Appl 14:77–99

Miller VC. A Quantitative Geomorphic Study of Drainage Basin Characteristics in the Clinch Mountain Area. Virginia and Tennessee, Project Number 389-402. Technical Report-3, Columbia University, Department of Geology, New York, 1953.

Mukherjee D (2013) Critical analysis of challenges of Darjeeling Himalaya: water, natural recourses, hazards and the implication of climate change. Int J Agr Innovat Res 2:2319–1473

Naef F, Scherrer S, Weiler M (2002) A process based assessment of the potential to reduce flood runoff by land use change. J Hydrol 267:74–79

Nanko K, Giambelluca TW, Sutherland RA, Mudd RG, Nullet MA, Ziegler AD (2015) Erosion potential under Miconia calvescens stands on the island of Hawai′i. Land Degrad Dev 26:218–226

Negley TL, Eshleman KN (2006) Comparison of stormflow responses of surface-mined and forested watersheds in the Appalachian Mountains, USA. Hydrol Process 20:3467–3483

Nepal S, Flugel WA, Shrestha AB (2014) Upstream downstream linkages of hydrological processes in the Himalayan region. Ecol Process 3:19

Noguchi S, Tsuboyama Y, Sidle RC, Hosoda I (1997) Spatially distributed morphological characteristics of macropores in forest soils of hitachi ohta experimental watershed, Japan. J For Res 2(4):207–215

O'Geen AT (2013) Soil water dynamics. Nat Educ Knowl 4(5):9

Penna D, Borga M, Sangati M, Gobbi A (2010) Dynamics of soil moisture, subsurface flow and runoff in a small alpine basin. Red Book Series 336, IAHS Publications, UKCEH Wallingford, Oxfordshire, ISBN 978-1-907161-08-7, 96-102

Penna D, Tromp-van Meerveld HJ, Gobbi A, Borga M, Dalla Fontana G (2011) The influence of soil moisture on threshold runoff generation processes in an alpine headwater catchment. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 15:689–702

Pereira DDR, Almeida AQD, Martinez MA, Rosa DRQ (2014) Impacts of deforestation on water balance components of a watershed on the Brazilian East Coast. Rev Bras Ciênc Solo 38(4):1350–1358

Pielke RA, Avissar R, Raupach M, Dolman AJ, Zeng X, Denning AS (1998) Interactions between the atmosphere and terrestrial ecosystems: influence on weather and climate. Glob Chang Biol 4:461–475

Poff NL, Allan JD, Bain MB, Karr JR, Prestegaard KL, Richter BD, Sparks RE, Stromberg JC (1997) The natural flow regime. Bioscience 47:769–784

Poirier JLP, Nguyen TT (2017) The inclusion of forest hydrological services in the sustainable development strategy of South Korea. Sustainability 9:1470

Qazi N, Rai SP (2018) Spatio-temporal dynamics of sediment transport in lesser Himalayan catchments, India. Hydrol Sci J 63(1):50–62

Qazi N, Kumar SR, Rai SP, Singh MP, Rawat SPS, Tiyagi JV, Tiwari RK (2012) Infiltration modelling for forested micro-watersheds in Mussoorie region of lower Himalayas. Water resources management in changing environment (WARMICE-2012)

Qazi N, Bruijnzeel LA, Rai SP, Ghimire CP (2017) Impact of forest degradation on streamflow regime and runoff response to rainfall in the Garhwal Himalaya, Northwest India. Hydrol Sci J 62(7):1114–1130

Qazi N, Jain SK, Thayyan RJ, Patil PR, Singh MK (2020) Hydrology of the Himalayas. In: Dimri AP, Bookhagen B, Stoffel M, Yasunari T (eds) Himalayan weather and climate and their impact on the environment. Springer Nature, Switzerland, p 575

Schumm SA (1956) Evolution of drainage systems and slopes in badlands at Perth Amboy, New Jersey. Geol Soc Am Bull 67:597–646.

Scott CA, Zhang F, Mukherji A, Immerzeel W, Mustafa D, Bharati L (2019) Water in the Hindu Kush Himalaya. In: Wester P, Mishra A, Mukherji A, Shrestha A (eds) The Hindu Kush Himalaya assessment. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 257–299

Sharma RK, Sankhayan PL, Hofstad O, Singh R (2007) Land use changes in the Western Himalayan region - a study at watershed level in the state of Himachal Pradesh, India. Int J Ecol Environ Sci 33(2):197–206

Sharma A, Singh OP, Saklani MM (2012) Climate of Dehradun. Indian Meteorological Department, Government of India, Ministry of Earth Sciences, Mausam Bhavan, New Delhi, p 69

Song S, Wang W (2019) Impacts of antecedent soil moisture on the rainfall-runoff transformation process based on high-resolution observations in soil tank experiments. Water 11:296

Stewart MK, Fahey BD (2010) Runoff generating processes in adjacent tussock grassland and pine plantation catchments as indicated by mean transit time estimation using tritium. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 14:1021–1032

Strahler AN (1957) Quantitative analysis of watershed geomorphology. Eos T Am Geophy Un 38:913–920

Strahler AN (1964) Quantitative geomorphology of drainage basins and channel networks. In: Chow VT (ed) Handbook of applied hydrology. McGraw Hill Book Company, New York Section 4–11

Struck M, Andermann C, Hovius N, Korup O, Turowski JM, Bista R, Pandit HP, Dahal RK (2015) Monsoonal hillslope processes determine grain size-specific suspended sediment fluxes in a trans-Himalayan river. Geophys Res Lett:2302–2308

Sudhishri S, Kumar A, Singh JK, Dass A, Nain AS (2014) Erosion Tolerance Index under different land use units for sustainable resource conservation in a Himalayan watershed using remote sensing and geographic information system (GIS). Afr J Agric Res 9(41):3098–3110

Tarboton DG (2003) Rainfall-runoff processes. Utah Water Research Laboratory, Utah State University http://www.engineering.usu.edu/dtarb. Accessed 15 Sept 2020

Thompson DD, Lewis C, Gray PA, Chu C, Dunlop WL (2011) A summary of the effects of climate change on Ontario’s aquatic ecosystems. Climate change research report. CCRR-11. Ontario, Canada

Thompson SA (1999) Hydrology for water management. CRC press, Taylor and Francis Group, p. 380

Tipper ET, Bickle M, Galy A, West AJ, Pomies C, Chapman HJ (2006) The short term climatic sensitivity of carbonate and silicate weathering fluxes: insight from seasonal variations in river chemistry. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 70:2737–2754

Tiwari VP, Verma RK, von Gadow K (2017) Climate change effects in the Western Himalayan ecosystems of India: evidence and strategies. Forest Ecosyst 4:13

Tiyagi JV, Rai SP, Qazi N, Singh MP (2014) Assessment of discharge and sediment transport from different forest cover types in lower Himalaya using Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT). Int J Water Res Environ Eng 6(1):49–66

Tobella AB, Reese H, Almaw A, Bayala J, Malmer A, Laudon H, Ilstedt U (2014) The effect of trees on preferential flow and soil infiltrability in an agroforestry parkland in semiarid Burkina Faso. Water Resour Res 50:3342–3354

Toro-Guerrero FJD, Vivoni ER, Kretzschmar T, Runquist SHB, González RV (2018) Variations in soil water content, infiltration and potential recharge at three sites in a Mediterranean mountainous region of Baja California, Mexico. Water 10:1844

Tyagi JV, Qazi N, Rai SP, Singh MP (2013) Analysis of soil moisture variation by forest cover structure in lower western Himalayas, India. J For Res 24(2):317–324

Varikoden H, Ravadekar JV (2018) Relation between the rainfall and soil moisture during different phases of Indian monsoon. Pure Appl Geophys 175:1187–1196

Venkatesh B, Lakshman N, Purandara BK, Reddy VB (2011) Analysis of observed soil moisture patterns under different land covers in Western Ghats, India. J Hydrol 397:281–294

Venkatraman K, Ashwath N (2016) Canopy rainfall intercepted by nineteen tree species grown on a phytocapped landfill. Int J Waste Resour 6:1

Walkley A, Black IA (1934) An examination of Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci 37:29–37

Wang W, Anderson BT, Entekhabi D, Huang D, Kaufmann RK, Potter C, Myneni RB (2006) Feedbacks of vegetation on summertime climate variability over the North American grasslands. Part II: A coupled stochastic model. Earth Interact 10(16)

Wang X, Xie H, Guan H, Zhou X (2007) Different responses of MODIS-derived NDVI to root-zone soil moisture in semi-arid and humid regions. J Hydrol 340:12–24

Wei X, Zhang M (2010) Quantifying streamflow change caused by forest disturbance at a large spatial scale: a single watershed study. Water Resour Res 46(12):W12525

WHO (1996) Total dissolved solids in drinking-water; background document for development of WHO guidelines for drinking-water quality, 2nd edn, vol 2. World Health Organization, Geneva

Zabaleta A, Antiguedad I (2013) Streamflow response of a small forested catchment on different timescales. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 17:211–223

Zokaib S, Naser GH (2011) Impacts of land uses on runoff and soil erosion: a case study in Hilkot watershed Pakistan. Int J Sediment Res 26(3):343–352

Zuazo VHD, Pleguezuelo CRR (2008) Soil-erosion and runoff prevention by plant covers. A review. Agron Sustain Dev 28:65–86

Zuecco G, Carturan L, De Blasi F, Seppi R, Zanoner T, Penna D, Borga M, Carton A, Della Fontana G (2018) Understanding hydrological processes in glacierized catchments: evidence and implications of highly variable isotopic and electrical conductivity data. Hydrol Process 33:816–832

Acknowledgements

Cordial thanks to Dr. Sharad Kumar Jain, Dr. Shive Prakash Rai and Dr. R.K. Tiwari for valuable support and Miss Smriti Srivastava for her support in GIS work. Author would also like to thank to DST for WOS-A project (No. SR/WOS-A/EA-1016/2015 (G)). Author thanks two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. Author would also like to thank Dr. Pottakkal George Jose for language editing.

Funding

Funding received from ICFRE and UCOST are greatly acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributed from data collection (from field) till manuscript development. Author have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The subject has no ethical risk.

Consent for publication

The subject matter has no ethical risk.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qazi, N. Hydrological functioning of forested catchments, Central Himalayan Region, India. For. Ecosyst. 7, 63 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-020-00275-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-020-00275-8