Abstract

While knowledge of the energy inputs from the Sun (as it is the primary energy source) is important for understanding the solar-terrestrial system, of equal importance is the manner in which the terrestrial part of the system organizes itself in a quasi-equilibrium state to accommodate and re-emit this energy. The ROSMIC project (2014–2018 inclusive) was the component of SCOSTEP’s Variability of the Sun and Its Terrestrial Impact (VarSITI) program which supported research into the terrestrial component of this system. The four themes supported under ROSMIC are solar influence on climate, coupling by dynamics, trends in the mesosphere lower thermosphere, and trends and solar influence in the thermosphere. Over the course of the VarSITI program, scientific advances were made in all four themes. This included improvements in understanding (1) the transport of photochemically produced species from the thermosphere into the lower atmosphere; (2) the manner in which waves produced in the lower atmosphere propagate upward and influence the winds, dynamical variability, and transport of constituents in the mesosphere, ionosphere, and thermosphere; (3) the character of the long-term trends in the mesosphere and lower thermosphere; and (4) the trends and structural changes taking place in the thermosphere. This paper reviews the progress made in these four areas over the past 5 years and summarizes the anticipated research directions in these areas in the future. It also provides a physical context of the elements which maintain the structure of the terrestrial component of this system. The effects that changes to the atmosphere (such as those currently occurring as a result of anthropogenic influences) as well as plausible variations in solar activity may have on the solar terrestrial system need to be understood to support and guide future human activities on Earth.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The primary goal of solar terrestrial physics is to understand the physical foundations of the structures and variability associated with the coupled Sun-Earth system. The challenges are significant, since the important physics of the various components of this system (Sun, Solar wind, magnetosphere, ionosphere, and atmosphere) differ and dominate in different spatial regions. Furthermore, the important time scales of the atmospheric responses to the forcings become longer closer to the surface of the Earth. Significant progress has been made in understanding the physics within each region. However, to facilitate progress, the boundary conditions linking the components have tended to be simplified. As a result, interactions between the different regions have not been realistic, and a full Sun to Earth system description has not been developed.

Recently, progress on establishing a full physically self-consistent understanding of the solar-terrestrial system has been made. This is due to the development of new observational techniques, advances in the sophistication and computing power of models, and the generation of tools allowing processes from the Sun to the Earth to be visualized and analyzed. This evolution is reflected in the nature of recent Scientific Committee on Solar-Terrestrial Physics (SCOSTEP) programs where investigation of the coupling between regions has been encouraged (see Shiokawa and Georgieva (2021)).

The recently completed VarSITI program (Variability of the Sun and Its Terrestrial Impact, 2014–2019) supported four projects: SEE (Solar Evolution and Extrema), MiniMax24/ISEST (International Study of Earth-affecting Solar Transients), SPeCIMEN (Specification and Prediction of the Coupled Inner-Magnetospheric Environment), and ROSMIC (Role Of the Sun and the Middle atmosphere/thermosphere/ ionosphere In Climate). Interactions between the various projects were encouraged. In PRESTO (PREdictability of variable Solar-Terrestrial cOupling), the 2020–2024 SCOSTEP science program, the system aspects of solar-terrestrial relations is further emphasized by defining projects in terms of their temporal and spatial relationships through the full system.

The ROSMIC project was devoted to understanding the impact of the Sun on the Earth’s middle atmosphere/lower thermosphere/ionosphere (MALTI) and its tropospheric climate. It sought to estimate the importance of this natural forcing over time scales from minutes to centuries, in a world where anthropogenic forcing is driving large-scale changes across all atmospheric regions. It was a continuation of the science initiated during the CAWSES (Climate And Weather of the Sun-Earth System) programs under which many of the intricacies and subtleties of the solar-terrestrial system started to be recognized. The essential insight was that the terrestrial component of the system plays an active role in determining the character of the system and its response to variations in solar input. On average, the terrestrial component of the system is in equilibrium with respect to solar inputs, i.e., the incoming and outgoing energy fluxes are equal. However, the physical properties of the terrestrial system and the non-local and non-linear processes that are involved determine the form that this equilibrium takes and its response to variations in solar input.

Two scientific issues stimulated work to develop insight into the terrestrial response. The first was that while significant sensitivity to solar variability in the stratosphere and troposphere is observed, the mechanisms causing these dependencies are difficult to determine (Gray et al. 2010). The second was the recognition that, in addition to radiation and energetic particles, much of the communication between layers of the atmosphere is due to waves (most of which are excited in the troposphere) and that these waves propagate to significant heights and cause ionospheric and thermospheric variability (Oberheide et al. 2015).

Over the course of the ROSMIC project, research into these issues has continued, and although they have not been settled, our understanding has advanced. The inconsistency between different observations and methods to determine the solar spectral irradiance variations is being resolved (Woods et al. 2015, 2018, Yeo et al. 2017). Together with total solar irradiance, solar spectral irradiance is now being included along with energetic particle forcing as input to model runs for the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) of the World Climate Research Program (Matthes et al. 2017). Investigations to identify the subtle processes leading to the solar influence of the lower atmosphere are progressing, and new challenges have been identified (Gordon 2020; Dhomse et al. 2016; Thiéblemont et al. 2015; Chiodo et al. 2019). New complexities in the upward coupling from the troposphere and stratosphere to the mesosphere, thermosphere, and ionosphere associated with waves are now being addressed. These include recognition of the importance of secondary gravity wave generation to wave penetration into the thermosphere (Becker and Vadas 2018) and pole-to-pole coupling of dynamical signatures (Karlsson and Becker 2016; Smith et al. 2020) and that the presence of wave signatures in the thermosphere and ionosphere need not be due to direct propagation (Miyoshi and Yamazaki 2020). Sudden stratospheric warmings and their global influences are being extensively studied (Butler et al. 2015; Pedatella et al. 2018a). They are the largest perturbations to the middle atmosphere on record and provide insights into the mechanisms of the coupling between atmospheric layers.

The need for coordinated ground observations and campaigns and associated modeling started to be addressed during ROSMIC. Examples include the Interhemispheric Coupling Study by Observations and Modeling (ICSOM) project, the Antarctic Gravity Wave Instrument Network (ANGWIN) (Moffat-Griffin et al. 2019), and The Deep Propagating Gravity Wave Experiment (DeepWave) (Fritts et al. 2016). Modeling advanced significantly with whole atmosphere models increasing in sophistication and including the ionosphere (Liu et al. 2018; Miyoshi et al. 2018; Solomon et al. 2019), and data assimilation efforts start to include mesospheric observations (Eckermann et al. 2018).

The scientific questions which guided ROSMIC activities were as follows:

-

What is the impact of solar forcing on the entire atmosphere? What is the relative importance of variability in solar irradiance versus energetic particles?

-

How are the solar signals transferred between the thermosphere and the troposphere?

-

How does coupling within the terrestrial atmosphere function (e.g., what are the roles of gravity waves and turbulence?).

-

What is the impact of anthropogenic activities on the MALTI?

-

Why does the MALTI show varying forms of long-term variations?

-

What are the characteristics of reconstructions and predictions of TSI and SSI?

-

What are the implications of trends in the ionosphere/thermosphere for technical systems such as satellites?

During VarSITI, ROSMIC supported the activity in the community through existing activities (i.e., Workshop on Coupling in the Atmosphere-Ionosphere System, ANtartic Gravity Wave Instruments Network (ANGWIN), High Energy Particle Precipitation in the Atmosphere/SOLAR Influences for SPARC (Stratospheric Processes and their Role in Climate) (HEPPA-SOLARIS) Workshop, 13th International Workshop on Layered Phenomena in the Mesopause Region (LPMR), and 9th IAGA - ICMA/IAMAS - ROSMIC/VarSITI/SCOSTEP workshop on Long-Term Changes and Trends in the Atmosphere) as well as through the organization of sessions at international meeting such at COSPAR, IUGG, and the VarSITI symposia.

This paper is organized as follows. The topic is introduced in an overview section which summarizes the physical context underlying the atmosphere/ionosphere components of the Sun/Earth system. This is followed by two sections which address the progress in the two most significant pathways for modulation and propagation of atmospheric/ionospheric responses to solar variability to solar variability namely coupling from above and coupling from below. The fourth section consists of a summary of progress in observing and understanding long-term trends in the mesosphere and thermosphere (this includes progress associated with themes 3 and 4). The paper concludes with a summary and thoughts on future progress in this area.

2 Overview: general physical principles of the energetics and organization of the atmosphere/ionosphere

Identifying the mechanisms which underlie the mean global atmospheric and ionospheric structures and their variability is especially important at this time. First, we do not fully understand the processes which couple the various regions of the atmosphere and ionosphere. Second, uncertainties remain in establishing the extent to which these structures and their variability might change in response to changes to solar inputs and/or to anthropogenically driven changes to atmospheric composition (especially those involved in radiative effects in the atmosphere). Either of these directly changes the thermal structure and circulation of the atmosphere and initiates a cascade of secondary effects associated with atmospheric waves and their filtering and the transport of radiatively active constituents. As noted in more detail below, many of these effects are non-linear and non-local and point to the complex and active character of the terrestrial part of the solar-terrestrial system.

The zeroth-order energy balance between solar radiation incident on the Earth and outgoing radiation from the Earth is well known and covered in most atmospheric texts. More complex considerations of the nature of this balance for the lower atmosphere can be found in review papers (Trenberth et al. 2009; von Schuckmann et al. 2016) where the effects of wind and current systems and eddies are also quantified. Thermodynamic considerations, involving the analysis of the total energy of the atmosphere (the sum of the internal and potential) relative to the energy of an isothermal reference atmosphere, provide some constraints on the partitioning of the energy. Recent analysis along these lines (Bannon 2013) shows that the percentage of the total energy of the atmosphere (2.5 Giga Joules) available for atmospheric motion (termed available potential energy) is a small percentage (< 1%) of the total energy although these motions are responsible for much of the meridional transport of energy toward the poles. This implies that much of the absorbed solar energy is devoted to maintaining the internal and potential energy of the atmosphere with a small amount being available for motion. In his analysis, Bannon (2013) suggests that the rate of conversion of available energy to kinetic energy is ∼ 5-7 W m −2. While this is small relative to the solar constant, 1361 W/m2, it plays an essential role in the terrestrial response to solar radiation, as it is associated with the poleward transport of energy and the global distribution of radiatively active constituents. An analysis along these lines, which identifies the vertical variation of the partitioning of the incident energy, appears not to have been undertaken to this point, although Kwak and Richmond (2017) have described the relative contributions of momentum forcing and heating in the lower high-latitude ionosphere, albeit without complete consideration of upward coupling.

Figure 1 summarizes the relationships between the components involved in establishing the large-scale structures of the middle atmosphere. The large-scale structural elements are in green, and the processes influencing their form are in blue. The complexity of these relationships is illustrated by considering the effects a shift in the thermal structure might have. Through thermal wind balance, the zonal wind structure would alter. These shifts in the thermal structure and zonal wind structure would modify the wave propagation conditions and location where the waves dissipate. This modification in dissipation location would induce secondary circulations and feedback into the thermal and wind structures. Changes to the winds would also affect the transport of constituents and possibly their distribution. Any effects that this transport might have on the distribution of radiatively active species would alter the heating, further feeding back into the thermal structure. The full impact of the initial change in thermal structure requires consideration of all these potential adjustments simultaneously. Changes to any other element would result in a similar cycle.

Links in the middle atmosphere. A schematic showing the relationship between various components affecting the large-scale structure of the middle atmosphere. The main elements appear in the green boxes, and the processes linking them appear in the blue boxes. The arrows indicate the direction of the influence. Although thermal wind balance links the zonal mean temperature and wind structure, wave and constituent fields affect the heating and momentum deposition leading to these structures and themselves depend non-linearly on these large-scale structures

Figures 2 and 3 are overview figures which provide a context for the processes and phenomena discussed later in this paper. Figure 2 is a schematic of the drivers of the coupling processes noted above. The solstice zonal mean temperature and wind structures are background fields in the figure with the temperatures being the color background (blue being cooler and yellow warmer)and the winds, the contouring (solid green, eastward; dashed blue, westward). The three regions of most significant solar radiative heating are indicated through the white boxes, the wave processes by orange boxes and black arrows, and the energetic particle precipitation by green boxes and arrows. The induced residual circulation is indicated by the white arrows. This figure provides an indication of the spatial relationships between the various processes.

The main drivers for coupling from above and below. The induced residual circulation is presented by white arrows. Black arrows represent the wave forcing and tides, as labeled. The color background represents the zonal mean temperature structure with blue indicating the coldest regions and yellow the warmest regions. The contour lines represent the zonal mean zonal wind structure (yellow is positive, i.e., eastward wind; dashed blue is negative, i.e. westward wind; black is the zero wind line). The radiative processes are in white, the elements of wave driving in orange, and downward particle precipitation in green

Overview of the MALTI phenomena. The schematic summarizes the phenomena/processes of importance to the coupling processes in the MALTI as well as ground based (left side of figure) and satellite observation techniques (right side of figure) and their altitude extent. Ovals identify significant sources of internal atmospheric variability, and squares, phenomena of importance. Vertical arrows represent the height range, and horizontal arrows, the latitude range over which the phenomena/processes have influence

Figure 3 presents the phenomena important to coupling processes in the MALTI. It includes phenomena relevant to the observation of these processes as well as drivers of variability which provide the means to empirically investigate coupling processes. These are all mentioned later in the paper. Also included is a summary of various ground-based and satellite observation types with the height ranges over which observations are provided. The background to the figure again is the solstice zonal mean temperature. Drivers of atmospheric variability are identified by ovals and include sudden stratospheric warmings (SSW), the quasi-biennial oscillation (QBO), and El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). The height range of their influence is indicated by the vertical white arrows. These phenomena cause variations in the large-scale wind and/or temperature fields and their variability which allow the strength and nature of the coupling processes to be investigated. Polar mesospheric clouds (PMC) appear in the summer upper mesosphere and are the result of up-welling over the summer pole associated with the induced residual circulation. The photochemistry involves the cycling of constituents from the well-mixed lower atmosphere into the thermosphere where they are dissociated and then diffuse downward to the mesosphere where they recombine to form the original molecular species. The cycling between molecular and atomic oxygen is particularly important for the formation of the airglow which provides an important means of probing the dynamics of the mesopause region. Ozone is a constituent whose distribution depends on photochemistry and transport. The downward transport of NO x which affects ozone chemistry is one of the significant mechanisms of downward coupling. The aurora is directly associated with downward fluxes of electrons along field lines and hence a signature of downward influence. The ionospheric dynamo and plasma bubbles are ionospheric phenomena whose form is influenced by upward propagating waves.

The main terrestrial-associated solar-terrestrial coupling components, namely energetic particle precipitation, solar irradiance absorption, and coupling associated with waves and constituent transport, are summarized briefly below. This serves as an introduction to the more detailed review of recent progress which follows. Of importance during the ROSMIC project was facilitating work which helped clarify the role and importance of these various processes in the atmosphere/ionosphere response to solar variability. Also of importance was work being undertaken to model and assimilate space weather effects on the ionosphere and thermosphere. This topic is not reviewed in this paper, but the interested reader can find a review of the current capabilities in Scherliess et al. (2019).

2.1 Energetic particles

Energetic charged particles, mainly electrons and protons from the Sun and the Earth’s magnetosphere, deposit energy into the atmosphere, particularly in the polar regions (see Fig. 2), where the particles are guided by the Earth’s magnetic field. Solar protons, ejected from the Sun, typically have energies between about 1 MeV to a few hundred MeV and have direct access to the high polar latitude middle atmosphere during solar proton events (SPEs) as shown in Fig. 4 (Seppälä et al. 2014). This range of energies means that they can directly impact the altitudes from the stratosphere to mesosphere. Energetic electrons, with auroral electrons with energies less than 10 keV, and medium energy electrons with energies from tens of keV up to a few MeV, originate in the magnetosphere and as a result of magnetospheric processes, enter the atmosphere near the auroral ovals (as shown in Fig. 4). Note that we will not explicitly cover galactic cosmic rays (GCR), which mainly impact the troposphere; here, the reader is directed to the recent comprehensive review article by Mironova et al. (2015).

Sources of EPP. The so-called medium energy electrons (MEE, >10 keV to several MeV) originate in the Earth’s outer radiation belt, and their fluxes into the atmosphere are understood to be controlled by magnetospheric wave-particle interactions. Auroral electrons (<10 keV) originate primarily from the plasma sheet which is located in the tail/night side of the magnetosphere, while solar protons (not included in the top image) are injected as a result of solar storms. The map in the bottom panel illustrates that the different types of particles can influence slightly different geographic areas when they enter the atmosphere (note that locations are only indicative and are influenced by the particle energies). While the Northern Hemisphere is shown here, precipitation also occurs in the Southern Hemisphere. For detailed information, see Matthes et al. (2017)

The process of all these particles interacting with the atmosphere is known as energetic particle precipitation, or EPP. As a result of EPP, whether of protons or electrons, ionization is enhanced, leading to production of odd-hydrogen (HO x= H + OH + HO2) and odd-nitrogen (NO x= NO + NO2) in the middle atmosphere. As these are both known catalysts in ozone loss reactions, solar influence via variations in EPP levels has implications to both atmospheric chemical and radiative balance hence potentially affecting surface climate via downward coupling of introduced wind anomalies (Seppälä et al. 2013). HOx is chemically short lived and thus so are its atmospheric impacts. In contrast, NOx produced by EPP (known as “EPP- NOx”) in the middle atmosphere is mainly destroyed by photolysis and so has a long chemical lifetime during polar winter. It is therefore subject to transport by the downward circulation over the winter pole. One of the challenges with estimating EPP effects is that, while good observations on proton fluxes and energy spectra during the large but sporadic SPEs exist, the limitations in electron observations have long hindered good characterization of both flux and energy spectrum of precipitating electrons. Unlike solar radiation, there is not a clear relation to the 11-year solar cycle, and the role of magnetospheric processes (such as those addressed in the VarSITI SPeCIMEN project) in electron precipitation provides another challenge in their quantification.

2.2 Solar irradiance variability

Solar radiation is the dominant energy input to the Earth system with about 70% absorbed by the atmosphere, land, and ocean, and the remainder scattered and reflected back to space (L’Ecuyer et al. 2015). This energy partially determines the temperature and structure of the atmosphere and warms the Earth surface. Globally, a delicate balance is maintained between incoming solar radiation, the Earth’s albedo (fraction of radiation reflected back to space), and outgoing long-wave infrared radiation that can be altered by greenhouse gases, clouds, and aerosols. Changes in solar irradiance have both direct and indirect effects on the Earth climate system, and the roles of solar irradiance are evident in many climate records (e.g., Solanki et al. (2013); Ermolli et al. (2013); Lean et al. (2005)). There are two dominant direct solar heating effects in the lower atmosphere: the “bottom-up” mechanism is the solar irradiance warming the Earth’s surface and upward coupling, and the “top-down” mechanism whereby solar ultraviolet radiation absorbed in the stratosphere couples downward. The winds and circulations in the atmosphere and oceans invoke complicated feedbacks that introduce non-linear and non-local responses (e.g., Meehl et al. (2008)). The solar radiation is also critically important in the Earth’s upper atmosphere. The solar vacuum ultraviolet (VUV: shorter than 200 nm) photons originate in the Sun’s chromosphere, transition region, and corona and deposit their energy in the Earth’s ionosphere, mesosphere, and thermosphere, being regions strongly influenced by space weather events like solar flares.

A well-known example of the non-linear response of the atmosphere to solar forcing (and an example of how the atmosphere modulates solar forcing) is what has been termed the natural “thermostat” effect (Mlynczak et al. 2003). During periods of enhanced geomagnetic effects (coronal mass ejections and particle precipitation) and variations in solar irradiance, the production of NO and the associated near-infra-red cooling is enhanced. As these events are also associated with enhanced heating of the atmosphere, the enhanced cooling serves to reduce the temperature response of the lower thermosphere to these inputs. The extent to which this process influences the cooling was described using 12 years of SABER observations by Mlynczak et al. (2014). Recent refinements to our understanding of this cooling process appeared in studies by Knipp et al. (2017) and Nischal et al. (2019).

The solar irradiance varies on all time scales with the key variations being the 11-year solar activity cycle (22-year magnetic cycle), the 27-day solar rotation variability, and short-term (seconds to hours) variability during solar flares. The solar variability is highly dependent on wavelength, which is related to the source regions in the solar atmosphere. The total solar irradiance (TSI: integrated over all wavelengths) and the solar spectral irradiance (SSI) in the near ultraviolet (NUV, 300–400 nm), visible (VIS, 400–800 nm), and near infrared (NIR, 800–3000 nm) comprises the bulk of the solar radiative energy and vary the least amount at about 0.1% over the 11-year solar cycle and typically have less variability for shorter time scales (e.g., Woods et al. (2018); Lean et al. (2005)). These NUV-VIS-NIR wavelengths are most important for climate studies for assessing the influence of the Sun on Earth and for comparison with other natural processes (such as volcanic eruptions and the El Niño Southern Oscillation) and human activity (such as greenhouse gas production from fossil fuel combustion). The SSI is much more variable in the ultraviolet (UV) ranges: middle ultraviolet (MUV; 200–300 nm), far ultraviolet (FUV; 120–200 nm), extreme ultraviolet (EUV; 10–120 nm), and soft X-rays (SXR, 0.1–10 nm) but involves only 1.5% of the solar radiative energy. The solar cycle variability in the UV is less than 15% for MUV wavelengths, about a factor of two for many EUV and FUV wavelengths, and even to factors of more than a 1000 for most SXR wavelengths (e.g., Woods et al. (2018); Woods and Rottman (2002)). These UV ranges are most important for atmospheric research and for space weather studies and applications involving satellite operations, communications, and navigation.

2.3 Transport and upward coupling through waves

The details of the chemistry and dynamics underlying the zonal mean structure of the stratosphere and mesosphere and its variability have been recently reviewed by Baldwin et al. (2018). Much of the structure of the middle atmosphere is due to a combination of radiative forcing and transport of momentum and constituents by mean flows (i.e., the residual circulation) and mixing which are driven in part by a broad spectrum of atmospheric waves. In the middle atmosphere, the combined effect of the residual circulation and mixing is now starting to be termed the Brewer-Dobson circulation (Baldwin et al. 2018). The current consensus is that the Brewer-Dobson circulation will be enhanced as a result of climate change. However, because of the complexities of the linkages between the different components identified in Fig. 1, exact drivers of this change remain difficult to determine (Butchart 2014).

The situation in the upper mesosphere and lower thermosphere remains less studied and understood. Recent advances in our knowledge of sudden stratospheric warmings reveal that the various regions of the atmosphere are closely coupled. The associated wave dissipation in the polar stratosphere not only influences the state of the middle atmosphere but drives global changes to the state of the thermosphere and ionosphere (Pedatella et al. 2018a). Nevertheless, details of the mechanisms which maintain the average conditions above the stratopause remain poorly understood. Wave dissipation in the mesosphere is considered important for the cycling of air through the stratosphere and mesosphere and associated age of air calculations (see for example Kovács et al. (2017)). The cycling of constituents and associated photochemistry across the mesopause region is still being examined in terms of global temporal means (Garcia et al. 2014; Gardner et al. 2019; Swenson et al. 2018) as opposed to zonal means or regional averages. There is indirect evidence of a wave dissipation-driven, lower thermosphere winter pole to summer pole circulation (opposite in direction to the better known residual circulation in the middle atmosphere) (Qian et al. 2017; Qian and Yue 2017) which provides some indication of zonal mean structures at these heights. Apart from this, there is little information on the seasonal variation and latitudinal structures of constituents and dynamics at these heights. This remains an important topic for future research.

The source of the wave activity is predominantly in the troposphere. As the waves propagate upwards, they interact with the mean wind and temperature fields, which influence their propagation and dissipation, and in turn, the stress associated with wave dissipation modifies the global fields. These wave processes are therefore non-linear and non-local. The nature of the wave field as a function of height was explored in detail in general circulation models of sufficient resolution and height (Shepherd et al. 2000; Koshyk and Hamilton 2001; Hamilton et al. 2008). They noted that the rotational components dominated the kinetic energy spectrum lower in the atmosphere with the divergent component becoming stronger with height and in the mesosphere becoming as strong as the rotational component. The divergent component is associated with atmospheric tides and gravity waves. Their increased relative importance above the stratopause is reflected in the extensive literature devoted to exploring gravity wave effects throughout the middle and upper atmosphere (and references therein Liu et al. (2014b); Yiğit and Medvedev (2015); Liu et al. (2017); Becker and Vadas (2018); Miyoshi and Yiğit (2019)). Of particular interest in these investigations is the analysis of SSWs as they provide the means to investigate structural differences in wave forcing and propagation for conditions which deviate significantly from normal (Manney et al. 2009; Goncharenko et al. 2013; Ern et al. 2016; Siddiqui et al. 2017; Pedatella et al. 2018b). The character of the waves penetrating and affecting the ionosphere and thermosphere is a topic that is of significant current interest and continues to evolve. The waves of interest and some of their characteristics are summarized by Liu (2016), and the density variations associated with various atmosphere and ionospheric phenomena are summarized in Liu et al. (2017).

3 Coupling from above

This section will focus on the aspects of coupling from above via solar forcing on the atmosphere and climate system. We will address EPP and solar irradiance separately. As there have been significant advances on the modeling capability that impact both, we will first address the latest progress in modeling during the VarSITI period and briefly discuss some remaining challenges. In this context, the earlier works of Gray et al. (2010) and Seppälä et al. (2014) outline the progress on the topic of solar influence on climate, as a result of previous SCOSTEP science programs. Many of the data sets important to this area are from satellite missions that are no longer active. The lack of planned future missions, important for validating models and new ideas on the nature of this coupling, is of considerable concern to the community.

The key questions initially identified by the Working Group on Solar Influence on Climate were as follows:

-

1.

Drivers of solar variability: How well do we know their magnitude and variability?

-

2.

Mechanisms and coupling processes: How is the solar signal transferred down to the troposphere and surface?

-

3.

Solar influence on climate: What are the uncertainties in establishing the long-term effect?

3.1 Progress and challenges in modeling

Various advances have been made in both improving modeling capability and identifying current limitations and future requirements. Reviews that contain details and insights to atmospheric modeling have recently been published by, e.g., Baldwin et al. (2018); Maher et al. (2019).

One issue of importance to modeling is the influence of solar UV irradiance on climate variability. Chiodo and Polvani (2016) addressed the limitations arising from the assessments of this influence when interactive (coupled) stratospheric ozone chemistry is not included. Model integrations with coupled chemistry are computationally expensive. For example, the WACCM (Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model) model has a throughput of 7.5 simulated years/day on the US–based Yellowstone supercomputer (Smith et al. 2014) with interactive stratospheric chemistry. This is increased to 14.8 simulated years/day with specified (non-interactive) chemistry with the same number of CPUs (central processing unit), nearly a doubling of performance. Thus, for better computational efficiency, interactive chemistry is often omitted. Chiodo and Polvani (2016) showed that inclusion of interactive stratospheric ozone chemistry reduces the surface warming signal from solar irradiance significantly, by a third, when contrasted to predictions from non-interactive (specified) chemistry. They conclude that models that do not take into account the responses in stratospheric chemistry are likely overestimating the surface level response to solar variability.

Another issue of importance is the credibility of model representations of the downward coupling of EPP-induced chemical responses. The multi-model, multi-satellite intercomparison work of Funke et al. (2017) examined how well various medium-top (model top lid at about ∼ 80 km) and high-top (model top lid above 120 km) models performed in this capacity. They examined the ability of these models to reproduce polar downward transport of high-altitude carbon monoxide and odd nitrogen (NO x= NO + NO2) as well as observed middle atmosphere temperatures during a dynamically perturbed Northern Hemispheric (NH) winter. The models performed reasonably well until the polar vortex was disrupted by a SSW event. These events frequently occur in the Northern Hemisphere causing major disturbances to the dynamical state of the atmosphere. They lead to the mixing of air masses and, sometimes, in the recovery phase, a reformation of the stratopause at typically mesospheric altitudes. These latter events are known as elevated stratopause (ES) events and can result in effective transport from the mesosphere and lower thermosphere (MLT) into the stratosphere (see also discussion in Section 4).

The descent of air masses as the newly formed stratopause moves downwards to 50 km is challenging for models to reproduce, with most simulating a too rapid return of the stratopause to its typical height. Funke et al. (2017) determined that model improvements are needed to address the lack of dynamical representation of ES events. To date, the closest representation of the downward descent following an ES event has required either relaxing (“nudging”) the model toward assimilated meteorological fields up to about the altitude of 90 km (Siskind et al. 2015), or the more self-consistent approach of using data assimilation in a chemistry climate model such as WACCM-DART (Pedatella et al. 2018b). This approach is only possible for times when meteorological observations (and thus assimilated products) are available and the models can be constrained to observed dynamics. The model improvements called on by Funke et al. (2017) have not been fully implemented and remain necessary to improve the dynamical capabilities of atmospheric and climate models.

Meraner et al. (2016) found that the parameterization of non-orographic gravity waves played an important role in improved representation of the MLT to stratosphere descent following ES events in the Hamburg Model of the Neutral and Ionized Atmosphere (HAMMONIA). Their results suggest that improvements to gravity wave parameterizations may need to be made to simulate realistic downward transport brought on by ES events. As the ES events can bring MLT air, rich in EPP- NOx, into the stratosphere, Randall et al. (2015) further highlighted the need to have a realistic representation of energetic particle precipitation (EPP) to bring down sufficient amount of NOx into the stratosphere.

The missing EPP contributions and the associated underestimation of EPP- NOx in the polar mesosphere have lead to two significant developments in climate modeling during VarSITI. Firstly, we now have the first long-term energetic electron precipitation (EEP) dataset for use in climate modeling. This is now incorporated into the recommended solar irradiance and energetic particle forcing for CMIP6 simulations (Matthes et al. 2017) and will be addressed further later in the Section 3.2. The second major improvement is the development of the first fully coupled climate model with comprehensive lower ionosphere (D-region) ion chemistry (307 reactions of 20 positive ions and 21 negative ions) (Verronen et al. 2016). This version of the WACCM model, the whole atmosphere component of the Community Earth System Model (CESM), called WACCM-D enables detailed studies of the global lower ionosphere and its response to external (e.g., solar) and internal (e.g., dynamical) forcing. WACCM-D includes fully interactive chemistry, radiation, and dynamics. For the purposes of EPP studies, the inclusion of detailed ion chemistry leads to improved representation of production of NOx and HOx gases, by removing the need for parameterizations, and the re-partitioning of nitrogen compounds (Andersson et al. 2016; Funke et al. 2017; Orsolini et al. 2018).

There has been an increased interest in the role of the stratosphere in tropospheric variability and the potential for improved predictions. While it still remains to be determined if stratospheric influence is relevant for daily weather forecasts (Baldwin et al. 2018), growing evidence is supporting inclusions of stratospheric information to produce skillful seasonal forecast from a few months to up to a year ahead (Thiéblemont et al. 2015; Dunstone et al. 2016). There are further indications that the ability to simulate stratospheric variability, whether in ozone, SSW occurrence or large-scale modes such as the quasi-biennial oscillation (QBO) leads to improvements elsewhere in the atmosphere/climate system (Baldwin et al. 2018). For the top-down coupling, this would suggest that mesospheric and thermospheric chemical and dynamical processes contributing to stratospheric variability also need to be investigated—one of the questions to be addressed in PRESTO (Shiokawa and Georgieva 2021) is the predictability in sub-seasonal to decadal variability for the atmosphere and climate.

3.2 Energetic particle precipitation

The widespread shift from SPE focused, event type studies (e.g., Funke et al. (2011)), toward more general consideration of EPP impacts on the atmosphere that we saw during the CAWSES-II program (Seppälä et al. 2014) has continued during VarSITI. The current consensus is that EPP, in the form of EEP, modulated by magnetospheric activity, is an important driver for the chemical variability of the polar middle atmosphere. This needs to be captured in chemistry-climate models in order to correctly represent natural polar ozone variability. Figure 4 illustrates some of the key differences in the sources and impact areas of SPEs and different types of EEP.

In particular, Stone et al. (2018) highlighted the need to account for SPEs when evaluating the recovery of stratospheric ozone due to chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). SPEs could have both direct (in situ) and indirect (via transported EPP- NOx) influences on stratospheric ozone. Denton et al. (2017; 2018) analyzed ozonesonde data from the NH polar region and found that, once seasonal background variability was taken into account, lower stratospheric ozone (altitudes below 35 km) was reduced in excess of 30 days from the start of the SPEs, with an average depletion of 5–10%. However, these results were recently disputed by Jia et al. (2020).

As SPEs are only a fraction of the total EPP, it is likely that further improvements on simulated ozone variability on decadal scales would arise from inclusion of EEP. This has been partially addressed by the development of the first EEP proxy model for inclusion of ionization from the so called “medium energy electrons” (with energies up to 1 MeV) in climate models (van de Kamp et al. 2016; Matthes et al. 2017; van de Kamp et al. 2018). As mentioned earlier, this is now the official input to CMIP6 model simulations going into IPCC AR6. Overall, the first EEP proxy is an underestimation of the total electron precipitation, and recent improvements to EEP observations (Peck et al. 2015; Nesse Tyssøy et al. 2016; Clilverd et al. 2017; Oyama et al. 2017; Nesse Tyssøy et al. 2019) will likely further aid our understanding of variability in this type of solar forcing into the atmosphere and lead to inclusion of more accurate levels of EEP in model studies (Smith-Johnsen et al. 2018).

To test the van de Kamp et al. (2016) EEP model, Andersson et al. (2018) ran simulations with the WACCM model to investigate the impact of inclusion of electron precipitation on middle atmosphere chemistry. They found that, on average, mesospheric ozone was reduced by up to 20% by inclusion of the new EEP forcing, while in the stratosphere, there was an additional 7% ozone loss when contrasted to simulations without EEP. They further noted that on solar cycle scales, the inclusion of EEP in WACCM doubled the stratospheric ozone response. These results can be contrasted to the multi-satellite observations presented by Andersson et al. (2014), who found that on solar cycle timescales, EEP can drive mesospheric ozone variations of up to 34%.

In their multi-satellite observational study, Damiani et al. (2016) showed evidence that EPP in general has influenced Antarctic upper stratospheric ozone since 1979, at a level of 10–15% O3 depletion on a monthly basis. This is slightly more than found by Fytterer et al. (2015), who estimated Antarctic ozone depletion of 5–10% using observations from a different set of satellite instruments. Using two independent chemistry-climate models (CCMs), Arsenovic et al. (2019) and Pettit et al. (2019) showed that only by including EEP were models able to reproduce stratospheric ozone anomalies found in satellite observations. A number of further studies (e.g., Zawedde et al. (2016); Smith-Johnsen et al. (2017); Smith-Johnsen et al. (2018); Newnham et al. (2018)) have demonstrated EEP impacts on both HOx and NOx gases.

Together, these suggest that there is need to improve the EEP forcing (the current EEP proxies are known to underestimate precipitating levels, see Nesse Tyssøy et al. (2019)) to ensure better representation of ozone variability in the middle atmosphere. A wider source of EEP are also likely to influence ozone variability in the mesosphere. Seppälä et al. (2015), Turunen et al. (2016), and Seppälä et al. (2018) investigated the potential impacts on mesospheric ozone levels from auroral substorms (which are known to occur frequently), pulsating aurora, and the more energetic relativistic electron microbursts, respectively. They found all to influence ozone levels by up to tens of percent, but thus far, this has not been verified from observations, nor is it clear to what extent these types of electron precipitation are included in the existing EEP proxy (Matthes et al. 2017).

To capture the descent of MLT NOx into the stratosphere, Funke et al. (2014b) analyzed 10 years of satellite observations from the Michelson Interferometer for Passive Atmospheric Sounding (MIPAS) instrument on-board the Envisat satellite. The instrument simultaneously measured several different middle atmosphere constituents, enabling the extraction of purely EPP produced reactive nitrogen, NOy, from the record. By the end of the polar winter/start of spring, the descent of NOy into the stratosphere was observed to reach altitudes of 30 km and below in the NH and 25 km and below in the SH during the time period studies. The results highlighted the asymmetries between the two poles arising from the very different dynamical conditions controlling the atmosphere in the north and the south: In the SH, Funke et al. (2014b) show a steady annual descent of EPP- NOy from the mesosphere to the stratosphere inside the stable SH polar vortex, with the overall amount of NOy depending on the solar cycle and level of geomagnetic activity. In the NH, not only did the overall levels of NOy depend on the solar and geomagnetic activity, but also the large dynamical variability present in the polar atmosphere. SSW/ES events had a significant impact on the descent rates as well as the amount and timing of the NOy reaching the stratosphere. Funke et al. (2014a) use these EPP- NOy observations to derive the total amount of NOy molecules in the polar atmosphere reaching altitudes below 70 km. They found a nearly linear correlation between the amount of NOy and the geomagnetic A p index for the winter period extending to early spring, confirming earlier works by Randall et al. (2007); Seppälä et al. (2007), with the NH again showing large responses to dynamical perturbations.

Based on these findings from the MIPAS data set, Funke et al. (2016) presented a semi-empirical, a p-driven, proxy model for EPP- NOy descending though mesosphere and upper-stratosphere. The model provides a seasonal dependent flux of EPP- NOy descending through given vertical levels. One of the main uses of this semi-empirical model is as an upper boundary condition (UBC) for chemistry-climate models to emulate the descent of NOy rich air from the MLT region. For CMIP6, the recommended way of taking into account production of EPP- NOx above the upper boundary of medium-top models is by employing the Funke et al. (2016) UBC (Matthes et al. 2017). Figure 5 outlines the different approaches of inclusion of sources of EPP in model simulations.

CMIP6 recommendation for including EPP in model simulations. The different approaches for auroral energy electrons (<10 keV), medium energy electrons (MEE), and solar proton events (SPE). For details, see Matthes et al. (2017)

Following from the work of Funke et al. (2014b), Gordon (2020) recently showed evidence that not only can EPP- NOx reach altitudes of 25 km and below by the end of the Antarctic polar winter, but once in the stratosphere, it remains in the stratospheric NOx column throughout the spring until breakup of the SH polar vortex. They found that the role of EPP in the springtime Antarctic stratospheric NOx column is modulated by the QBO. They proposed that as CFCs are reduced, EPP- NOx will likely take a larger role in Antarctic springtime ozone loss processes.

As we see from above, there is a growing body of evidence that EPP plays an important role in atmospheric chemical balance, extending to decadal scales. Including this source of variability in medium-top and high-top models is now possible for the first time due to development of the CMIP6 EPP forcing input and the EPP- NOx UBC (Matthes et al. 2017), but further improvements are still needed. Questions remain unanswered at the end of the VarSITI program: What is the exact size of the EEP- NOx source and how important is overall EPP-induced chemistry to climate variability?

While the latest meteorological re-analysis investigations (e.g., Maliniemi et al. (2018); Salminen et al. (2019)) continue to suggest that there are important implications to atmospheric dynamical variability on decadal scales, the results from simulations with a range of CCMs are somewhat inconclusive (Arsenovic et al. 2016; Meraner and Schmidt 2018; Sinnhuber et al. 2018), particularly when it comes to relevance of EPP forcing to surface level climate variability. However, importantly, results from the latest model studies by Arsenovic et al. (2016), and the multi-model study by Sinnhuber et al. (2018) are in agreement with earlier model investigations (Baumgaertner et al. 2011), and also with earlier meteorological reanalysis studies (Seppälä et al. 2013). They found that inclusion of EPP resulted in changes in polar winter stratospheric temperatures (Arsenovic et al. 2016) or radiative heating patterns (Sinnhuber et al. 2018). The Sinnhuber et al. (2018) study further found that state-of the-art models accounting for EPP are able to reproduce observed chemical effects. The introduced radiative forcing changes in the polar stratosphere are of a similar order to those caused by UV variability in the tropics, however, with alternating sign in mid winter (polar night) and spring.

Recently, Maliniemi et al. (2020) addressed the benefit of accounting for the full description of the CMIP6 solar forcing (both irradiance and EPP) in future projections. By looking at the amount of NOx descending into the stratosphere, they were able to conclude that climate change will likely increase the EEP-related atmospheric effects toward the end of the century.

3.3 Solar irradiance

This section will outline the recent progress in the understanding of variability in solar irradiance, in both long-term (solar cycle scales) and short-term, models of solar variability, and, finally, the atmospheric and climate impacts.

3.3.1 Long-term variability—solar cycle

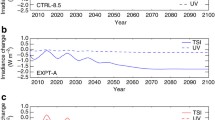

The nearly periodic 11-year solar cycle is manifested by the regular presence of numerous large sunspots during solar maximum and few, if any, sunspots during solar minimum. These sunspots are the result of magnetic activity rising up through the Sun’s photosphere. Three decades of space-based research document dramatic increases in solar photon, particle, and plasma energy output accompanying the increase in sunspot numbers. Figure 6 shows that in the recent solar cycles 23 and 24, the TSI increased during the maximum by about 0.14% relative to solar minimum and that the SSI H I Lyman- α emission at 121.6 nm increased by about a factor of 1.7 at maximum relative to minimum. It is also important to note the difference in cycle maximums. In particular, the ratio of the solar variability, defined as maximum minus minimum, at cycle 24 maximum to the variability in cycle 23 is 0.84 for TSI and 0.65 for Lyman- α. Moreover, cycle 24 maximum has proven to be the weakest during the past 90 years.

Solar variability over solar cycles 23 and 24. Examples of solar variability over solar cycles (SC) 23 and 24 for a the total solar irradiance (TSI) and b the bright ultraviolet H I 121.6 nm Lyman- α emission. The SORCE TSI observations shown here are being extended with TSIS-1 observations. Important solar UV irradiance records over solar cycle (SC) 23 and 24 have been established with TIMED SEE observations, and the TIMED SEE and SDO EVE observations will be extended into the next solar minimum and cycle 25. These extensions are particularly important for overlapping with the new GOLD and ICON missions to observe the ionosphere-thermosphere during cycle 25

As described earlier, the SSI variability is very wavelength dependent. The solar cycle variability for the SSI as a function of wavelength is shown in Fig. 7. These observations are from NASA’s Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE (Rottman et al. 2005)), launched in 2003 and also the Thermosphere Ionosphere Mesosphere Energetics and Dynamics (TIMED (Woods et al. 2005)) spacecraft, launched in 2001. The exact amount of SSI variability from the SORCE mission is under debate primarily in the visible where the amount of variability is smaller than the measurement uncertainty and in the near infrared (NIR) where many wavelengths have out-of-phase (negative) variability over the solar cycle (e.g., Ermolli et al. (2013)). The NASA Total and Solar Spectral Irradiance Sensor (TSIS-1) observations that started in 2018 are anticipated to address the SSI variability more accurately for the visible and NIR ranges.

SORCE solar spectral irradiance variability. The SORCE solar spectral irradiance variability results from Woods et al. (2015), shown in black, are compared to the SATIRE-S (blue) and NRLSSI (red) model estimates for solar variability between February 2002 (max) to December 2008 (min). The top panel shows the relative variability in percent, and the bottom panel shows the absolute variability in irradiance units. The dashed lines are out-of-phase (negative) solar cycle variability results. The irradiance variability (max-min) in broadbands is provided, and those numbers are in units of mW/m2. The total variability is for the 115 to 1600 nm range. This figure is adapted from Woods et al. (2015)

The TSI at the 2008–2009 minimum also appears to be lower by 0.2 W/m2 (− 140 ppm) than the previous minimum in 1996 (Fröhlich 2009); however, the 100 ppm uncertainty of this TSI change makes this finding less certain (e.g., Kopp and Lean (2011)). Observations taken during the next solar minimum in 2019–2020 will be very intriguing in terms of determining whether the secular trend of lower solar activity is continuing or not. There are already some indications that the solar activity could continue to decline as indicated from studying the overlapping solar activity bands of the 22-year solar magnetic cycle (McIntosh et al. 2015). Furthermore, this next cycle minimum in 2019–2020 will be characterized even better than the 2008–2009 minimum (e.g., Chamberlin et al. (2009); Woods et al. (2009)) with the continuation of the SORCE, TIMED, and SDO missions and the addition of new ionosphere-thermosphere measurements by NASA’s Global-scale Observations of the Limb and Disk (GOLD (Eastes et al. 2017)) and Ionospheric Connection Explorer (ICON (Immel et al. 2018)).

3.3.2 Short-term variability—flares

Solar flares have long been an interest for sudden ionosphere disturbances and their effect on radio communication (e.g., Dellinger (1937)). Flare observations have been made for decades in the visible, primarily in H- α (e.g., Ellison (1946)), and also in the SXR and EUV ranges from sounding rocket and satellite experiments (e.g., Friedman (1963)). Hudson (2010, 2011), Doschek and Feldman (2010), Lang (2009), and Aschwanden et al. (2009) provide reviews of recent progress in understanding flares from observations that involve the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), Transition Region and Coronal Explorer (TRACE), Reuven Ramaty High Energy Solar Spectroscopic Imager (RHESSI), Hinode (Solar-B), and Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory (STEREO) missions. These satellites include imagers in X-ray and EUV broadbands and imaging spectrographs with high spectral resolution, but over a limited EUV range.

The new and exciting aspects of solar irradiance observations for flare studies are with the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) EUV Variability Experiment (EVE (Woods et al. 2012)). They include spectral coverage over the full EUV range from 0.1 to 106 nm with 0.1 nm resolution and the continuous monitoring of the solar activity at a high cadence of 10 s. There is also a continuous monitoring of the solar EUV images with cadence of 12 s with the SDO Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA (Lemen et al. 2012)). The AIA image time series permit physical interpretation of the EVE (full-disk) irradiance flare variability. The EVE flare observations have revealed that many EUV emissions do not behave like the X-ray variations that are often used for classifying the flare magnitude and as a proxy for EUV emissions in models such as the Flare Irradiance Spectral Model (FISM (Chamberlin et al. 2007; Chamberlin et al. 2008)). Therefore, the EVE flare observations are important to improve the understanding of flare energetics and their impacts on Earth’s space environment.

Flare events can be studied in detail with EVE’s full-disk EUV spectral irradiance as long as only one major flare is happening at a time, which happens frequently. Woods et al. (2011) provide examples of the four major phases seen during flares with the EVE data. These phases include (1) the impulsive phase best seen in transition region emissions such as He II 304 Å, (2) gradual phase seen in hot coronal emissions such as the Fe XX/Fe XXIII 133 Å, (3) coronal dimming seen in cool corona emissions such as Fe IX 171 Å, and (4) EUV late phase (ELP), which has a second, broad peak one to 5 h after the main flare phases and seen best in the Fe XVI 335 Å emission. The X-ray flare classification by the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES) X-Ray Sensor (XRS) is based on the peak SXR variations during the gradual phase, and the derivative of the GOES XRS 1-8 Å emission can be a proxy for the impulsive phase, as related to the Neupert effect (Neupert 1968). Prior to EVE observations, flare observations in the SXR and radio wavelengths were usually decomposed into an impulsive phase with significant non-thermal signatures and a gradual (slow) mostly thermal phase that follows the impulsive phase (Donnelly 1976; Hudson 2010; Hudson 2011). The coronal dimming and EUV late phase effects are observable primarily in the EUV emissions. Each flare can have its own unique behavior; some flares have all four of these phases, and some flares only have the gradual phase (by definition from the X-ray flare identification by GOES/XRS). For more detailed information, Hudson (2010) reviews flare processes and phases, and Hock (2012) identifies different categories of flares based on the new SDO/EVE and SDO/AIA observations of hundreds of flares. Notably, the eruptive flares tend to have impulsive phase, gradual phase, and coronal dimming, and some eruptive flares also have the EUV late phase. The C8.8 flare on 2010 May 5 is a good example when all four components clearly exist as shown in Fig. 8. The various EUV emissions have one or more of these aspects in their time series, and the four emissions that best highlight each component are included in this figure. The EUV spectral variations during this C8.8 flare are shown in Fig. 9.

Example of flare variations. Flare variations for the C8.8 flare on 2010 May 5 as adapted from Woods et al. (2011). The relative irradiance (Rel. Irr.), being the solar irradiance spectrum minus the pre-flare spectrum, represents well the flare variations over its different phases. The transition region He II 30.4 nm emission highlights the impulsive phase. The GOES X-ray (0.1–0.8 nm) defines the gradual phase, and the hot corona Fe XX / Fe XXIII 13.3 nm emission behaves almost identically as the X-ray. The cool corona Fe IX 17.1 nm emission is the EUV emission with the largest amount of coronal dimming that often follows after the impulsive phase. The warm corona Fe XVI 33.5 nm emission has its first peak a few minutes after the X-ray gradual phase peak and then has a second peak many minutes later. The change in slope of the GOES X-ray during the gradual phase is indicative of the late phase contribution (second Fe XVI peak). The four vertical dashed lines, left to right, are for spectra in Figure 9 of the pre-flare, main phase, coronal dimming, and EUV late phase

Flare spectral variations from the EVE MEGS Flare spectral variations from the EVE MEGS A channel (6–37 nm) for the C8.8 flare on 2010 May 5 as adapted from Woods et al. (2011). A The pre-flare spectrum. B–D The variability between the pre-flare irradiance and the main phase, coronal dimming, and EUV late phase, respectively. These results used 5-min averages taken at the times indicated in Fig. 8 as vertical dashed lines

[Prior to the SDO mission, the flare irradiance models have been using the GOES X-ray signal as a proxy for the gradual phase and the derivative of the X-ray signal as a proxy for the impulsive phase emissions. It is clear now with the SDO EVE and AIA measurements that at least two additional flare components—(a) coronal dimming for cool coronal emissions and (b) an EUV late phase for warm coronal emissions—are required for improved modeling of the EUV irradiance. [While coronal dimming and long-duration events like post-flare giant arches have been known for some time, their impact on EUV irradiance is now being clarified with the new SDO observations. The new EVE results are also very important for many space weather applications as deposition of the solar EUV irradiance into the Earth’s atmosphere depends on the spectral variability and on the timing that determines the local (regional) effects on Earth. For example, the ionospheric F layer is expected to have an additional increase one to 5 h after the GOES X-ray peaks for EUV late phase flares. These late-phase flares can be significant because they can enhance the total EUV irradiance flare variation by a factor of 40% or more when the EUV late-phase contribution is included. Furthermore, the occurrence of late-phase flares are clustered before and after each solar cycle minimum and has a minimum frequency of occurrence during cycle maximum (Woods 2014). Another advance is that the coronal dimming observations can serve as proxies for the mass and velocity of Earth-directed coronal mass ejections (CMEs) (Mason et al. 2014; Mason et al. 2016).

3.3.3 Models of solar variability

There are several models of the solar spectral irradiance variability that provide temporal coverage when there are gaps in the observations and also for extending back to times prior to the advent of satellite solar measurements. The physics-based solar irradiance models, such as the Solar Radiation Physical Model (SRPM (Fontenla et al. 2011; Fontenla et al. 2014)), can also provide insight into the causes for the solar variability. A few of the more commonly used models for climate studies (e.g., CMIP6) are the Naval Research Laboratory TSI model (NRLTSI (Lean et al. 2005)), Naval Research Laboratory SSI model (NRLSSI (Lean et al. 2005; Lean et al. 2011), NRLSSI2 (Coddington et al. 2016)), and Spectral and Total Irradiance Reconstruction (SATIRE (Ball et al. 2014; Krivova et al. 2011; Wenzler et al. 2004; Fligge et al. 2000)). These models provide daily estimates for the solar variability and also extend back to the Maunder Minimum period, a time of low solar activity in the 1600s. It should be noted that, as pointed out by Matthes et al. (2017), some of the models show a discrepancy over the last three solar cycles: while SATIRE predicts a significant downward trend of the baseline SSI at solar minimum, this is not as apparent in NRLSSI2 (a combinaton of these models is used for CMIP6 recommended SSI and TSI forcing datasets).

For space weather studies, the models need to be at high cadence of at least once a minute in order to describe flare variations. The Flare Irradiance Spectral Model (FISM (Chamberlin et al. 2007; Chamberlin et al. 2008)) is one of the solar irradiance models used for studying flare effects in the ionosphere and thermosphere (e.g., Qian et al. (2019b)). FISM has also been extended to be used at Mars (FISM-M (Thiemann et al. 2017)), and similar algorithms as used by FISM have been adopted for NOAA’s operational solar irradiance model (Thiemann et al. 2019).

3.3.4 Influence of solar variability on the atmosphere and climate system

Representation of variations in solar irradiance, both in TSI and SSI, as outlined in the above sections, is of high importance for capturing the influence the Sun has on the atmosphere and climate system. Not only does it link directly to radiative heating, but solar radiation (in the UV) also modulates stratospheric ozone budget (for detailed descriptions of the processes, see, e.g., (Gray et al. 2010; Matthes et al. 2017)).

Kodera et al. (2016) provide a recent update on understanding of the physical mechanisms for solar radiative forcing of the Earth’s surface, through coupling of the stratosphere and troposphere, including interactions with the ocean and sea surface temperatures (SST). They write that “The role of the ocean as heat storage can be seen as persistent surface temperature anomalies from winter to spring. In addition, ocean currents advect SST anomalies to higher latitudes, which may introduce further delayed response.” Kodera et al. (2016) highlight how zonal mean zonal wind anomalies extend from the stratosphere into the troposphere during winter, but these disappear in the spring as the polar-night jet dies out. This is found to coincide with temperature anomalies diminishing over continents, while those over ocean basins (east of continents) are still developing. They also point to the role of oceanic frontal zones (regions of strong temperature gradients in SSTs and surface air temperatures forming in regions of confluent cool and warm ocean currents) as one of the key regions where solar cycle related surface level warming takes place.

The solar minimum between cycles 23/24 was anomalous with regard to its length as well as its depth and thus could provide new insights in the longer term (secular) variations that underlie the 11-year activity cycle. Satellite drag data indicate that the thermosphere was lower in density, and therefore cooler, during the protracted solar minimum period of 2008–2009, than at any other time in the past 47 years (Emmert 2009). Satellite measurements indicate that solar EUV irradiance was also lower in 2008 than during the previous solar minimum. However, secular change due to increasing levels of CO2 and other greenhouse gases, which cool the upper atmosphere, also plays a role in thermospheric climate, and changes in geomagnetic activity could also contribute to the lower density. Solomon et al. (2010); Solomon et al. (2011); Solomon et al. (2013) conclude that CO2 and geomagnetic activity play small but significant roles and that the primary cause of the low temperatures and densities is the unusually low levels of solar EUV irradiance.

The upper atmosphere and ionosphere are influenced by forcing from above through solar cycle variations, short term solar flares, or dissipation of magnetospheric energy. Within the ROSMIC period, ESA’s Swarm satellite mission (Olsen et al. (2013)) started orbiting the Earth in 2013. Due to its nature as a geomagnetic mission, its data were mainly explored to investigate ionospheric current systems in the E- and F-region. These were often successfully combined with data from the CHAMP mission (2000–2010) to achieve a multi-year data set.

Many of the results associated with these missions are relevant to coupling from below (see the Section 4.3 below). However, solar and geomagnetic effects were also addressed. These have been reviewed in several papers. Laundal et al. (2018) developed an empirical model of the high-latitude E-region and auroral field-aligned currents and their responses to the direction and strength of the solar wind for different seasons, during geomagnetically quiet and active times Alken et al. (2017) and Yamazaki and Maute (2017) reviewed the current knowledge mid- and low-latitude currents in the F-region and E-region (the latter Sq and EEJ), respectively, derived climatological behaviors from these long-term observations, and compared and assessed recent model results to simulate these currents.

Maycock et al. (2016) revisited our understanding of the solar cycle signal in stratospheric ozone, using updated satellite datasets. They found that on annual scales, the signal in stratospheric ozone is much smaller than previously estimated, but note potential, substantial, monthly scale variations. Ball et al. (2019) used new ozone composite datasets to also estimate the solar signal in the upper stratosphere. They determined a statistically significant “U-shaped” annual mean response (peaking at approximately 3% near the equator) that is likely the imprint of seasonal response variations. Good agreement was found with model simulations using the SOCOL and WACCM models.

Dhomse et al. (2016) called into question how well we understand the response of upper stratospheric ozone to the 11-year solar cycle. They suggest that there may be large uncertainties in observations, the impact from changing GHG emissions, recent changes in the amplitude of the 11-year solar cycle, and potential challenges arising from meteorological reanalysis data sets. While, on annual scales, the solar cycle signal in stratospheric ozone may be smaller than previously estimated, accounting for this solar cycle ozone response in global models is important. This was highlighted by Maycock et al. (2018) where they pointed to the necessity of accounting for the ozone response to adequately capture solar cycle impacts on the atmosphere. How this is done must be carefully considered, particularly for models that do not have interactive chemistry.

The influence of the 11-year solar cycle on North Atlantic via the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) has been a topic of high interest, particularly in the past two decades. This is not least due to the potential increased predictability of large scale climate patterns influencing the large metropolitan areas around the North Atlantic and extending into central Asia. Recently Thiéblemont et al. (2015), Gray et al. (2016), and Roy (2018), found further evidence of the link between the solar cycle and these large scale climate patterns, pointing to the role of downward propagation of the solar signal from the stratosphere to the troposphere. However, Chiodo et al. (2019) proposed that the signal in the North Atlantic climate that several previous studies have attributed to the 11-year solar cycle is, in fact, a chance occurrence, resulting from internal variability in the climate system. If this is the case, it would limit the usefulness of the 11-year solar cycle as a predictor for large scale circulation. The authors note that there are several caveats that may affect their conclusions, but nonetheless, call for much needed caution when interpreting quasi-decadal signals, such as those from the solar cycle, in the existing, relatively short, observational records. In this context, studies providing insights into the detailed physical mechanisms behind the so called “top-down” coupling are important. investigations such as that by Lu et al. (2017b); Lu et al. (2017a) who investigate roles of planetary wave breaking, reflection and resonance in the propagation of the solar signal from the stratosphere to the troposphere, may be able to provide some further understanding of the details of the solar cycle signals in climate.

As discussed earlier, there have been some indications that solar activity could continue to decline in the next decades. Changes in the solar input warrant further investigation to assess the potential impact of a potential future “grand solar minimum.” Following initial work by Meehl et al. (2013), Maycock et al. (2015) and Ineson et al. (2015) investigated the combined effects of lower solar activity (0.12% reduction in TSI, 0.85% reduction in UV), reducing ozone depleting substances and increasing GHG concentrations. They confirmed that there was negligible impact on global mean surface temperatures (around −0.1 K), which could not offset the projected impacts of anthropogenic climate change. However, the predicted regional-scale changes were much larger, particularly for mid- to high latitudes. Both the polar vortex and the tropospheric midlatitude jet were found to respond to the reduced solar activity (indicating links to top-down coupling) resulting in changes in large scale dynamical patterns in both hemispheres. These in turn could potentially drive “larger regional scale surface climate effects” (Ineson et al. 2015), highlighting the need to carefully consider changes in both anthropogenic and natural drivers together when assessing future projections.

3.4 Future challenges

What will the Sun do in the future? Variations in the 11-year solar cycle as well as longer cycles are important for any future projections of the state of the atmosphere and climate. Continued observations of solar activity both for radiation and particles is vital for our understanding. At the same time from the atmosphere side, we are relying on aging missions to detect changes in atmospheric composition in response to forcing from above and below. The growing unease in the scientific community has not diminished during VarSITI: we are heading into the future relying more and more on models that continue to need a “ground truth” from satellite observations to enable increased accuracy.

What will be the role of solar forcing for climate in the future? One of the big challenges we are now facing is understanding how the atmosphere and climate response will adjust due to changes brought on by enhanced GHGs and climate change, recovery of the Antarctic ozone hole (which will influence both the chemical and dynamical state of the SH atmosphere), and even the potential future grand solar minimum—together. Most studies thus far have focused on the solar irradiance changes but with the developing EPP proxies we are now seeing the first evidence that there is benefit in accounting for the full description of the CMIP6 solar forcing in future projections (Maliniemi et al. 2020). On a smaller scale, the question on whether there is improved seasonal prediction skill from inclusion of solar activity is showing some promise.

4 Coupling from below

ROSMIC’s working group “Coupling by Dynamics” focused on the dynamical and thermodynamical processes originating in the lower and middle atmosphere, influencing the upper atmosphere. Modeling, observations, and theoretical studies have all been relevant to the interests of this working group. In addition to the physical processes impacting the atmosphere-ionosphere system from above discussed in the Section 3, upward propagating lower atmospheric processes can shape the structure and evolution of the upper atmosphere. This is generally referred to as “coupling from below.” The key science questions of the Coupling by Dynamics Working Group have beena as follows:

-

1.

Wave coupling: What are the influences of lower atmospheric waves on the state and evolution of the thermosphere-ionosphere?

-

2.

Electrodynamic coupling: How does atmospheric dynamics constrain electrodynamics in the ionosphere?

-

3.

Small-scale dynamics: How can we characterize significance of small-scale structures for the large-scale features in the upper atmosphere?

These science questions have been actively studied by the solar-terrestrial community and fostered collaborations among atmospheric and space scientists. The vast majority of the recent studies have indicated that the primary mechanism of coupling from below is via internal atmospheric waves. As noted in the Overview (see Figs. 1 and 2 for a schematic context), they play a role in the transfer of energy and momentum, the mixing of constituents, and development of large-scale flows where they dissipate and atmospheric and ionospheric variability wherever they are present. Their role in the downward propagation of NOx and the formation of elevated stratopauses has already been mentioned in the section on downward coupling.

Overall, the lower atmosphere is the primary source of internal waves. At higher altitudes in the atmosphere higher-order waves can be found (Satomura and Sato 1999; Yasui et al. 2018; Becker and Vadas 2018), which are produced via either primary waves or other dynamical and thermal processes, such as instabilities and localized heating taking place in situ. These waves span a broad spectrum of periods (or frequencies) and horizontal and vertical scales. The key components of the spectrum of atmospheric waves are gravity waves, tides, Kelvin waves, and Rossby-planetary waves, covering a range from a few tens of kilometers to several thousand kilometers. The influence of the upward propagating waves can be substantially modulated by lower and middle atmospheric transient processes, such as sudden stratospheric warmings (Pancheva et al. 2008; Pancheva et al. 2009; Tomikawa et al. 2012; Nayak and Yiğit 2019; Yiğit and Medvedev 2012; Yiğit et al. 2014; Yiğit and Medvedev 2016; Pedatella et al. 2018a; Yamazaki et al. 2020). These modulations occur primarily due to the underlying changes in the background atmospheric circulation and temperature, which directly effect wave propagation and dissipation.

Comprehensive reviews of how upward propagating internal waves influence the upper atmosphere and ionosphere have been recently provided in the work of Yiğit and Medvedev (2015) and Liu (2016). Figure 10 adopted from Yiğit and Medvedev (2015) gives a good overview of the different neutral atmospheric and ionospheric layers and coupling from below. They discuss various theoretical, numerical modeling, and general circulation modeling approaches to internal waves, as well as observation of internal wave activity in the middle and upper atmosphere. In particular, the importance of SSWs has been highlighted in their review of wave-induced processes. The review by Liu (2016) concentrates on the variability in the ionosphere and thermosphere associated with waves.