Abstract

ᅟ

We show that the spatial heterogeneity in the coseismic displacement of large earthquakes likely reflects the spatial characteristics of the frictional properties and that it can be inferred from the stress drop of moderate-sized earthquakes. We analyzed stress drops of 686 earthquakes with magnitudes of 4.0 to 5.0 off the south-east of Hokkaido, Japan, and investigated the spatial heterogeneity between the difference of shear strength and dynamic stress level on the Pacific Plate. We deconvolved observed P and S waves with those of collocated small earthquakes and derived the source effect of the earthquakes. We then estimated the corner frequencies of the earthquakes and calculated stress drops using a circular fault model. The values of stress drops showed a spatial pattern consistent with slip distributions of historical large earthquakes. Earthquakes that occurred in the area with a large coseismic slip during the 1968 Tokachi-oki (M W 8.2) and the 2003 Tokachi-oki (M W 8.0) earthquakes had large values of stress drop, whereas earthquakes in the afterslip area of the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake showed smaller values. In addition, an area between coseismic ruptures of the 1973 Nemuro-oki (M W 7.8) and the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquakes had a large value of stress drop. Ruptures occurred in this area during the 1952 Tokachi-oki earthquake (M W 8.1), and the area acted as a barrier during the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake. These facts suggest that the frictional properties of the plate interface show little temporal change, and their spatial pattern can be monitored by stress drops of moderate-sized earthquakes. The spatial heterogeneity provides important information for estimating the slip pattern of a future large earthquake and discussing a policy for disaster mitigation, especially for regions in which slip patterns of historical large earthquakes are unclear.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Numerous large earthquakes have been observed off the south-east of Hokkaido, Japan, due to the subduction of the Pacific Plate beneath the Okhotsk Plate at a rate of 80–100 mm/year (e.g., DeMets et al. 1990). Previous studies have suggested that the frictional properties of the plate interface in this region exhibit spatial heterogeneity.

Yagi (2004) analyzed the source rupture process of the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake (in Japanese, X-oki means “off the coast of X”) and found that an area with a large coseismic slip in the shallower part had a longer rise time than the area in the deeper part of the fault plane. They pointed out that the difference should be attributed to the spatial variety of the frictional properties. Miyazaki et al. (2004) analyzed the spatial distribution of the afterslip following the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake using GNSS data. They found that areas with a significant afterslip were located around the coseismic rupture area, especially at the shallower plate interface. Miyazaki et al. (2004) investigated the spatio-temporal evolution of the afterslip in detail. They found that the slip-rate history of the afterslip in the coseismic area during the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake was significantly different from that around the area where significant afterslip was observed. They also concluded that the difference indicated spatial variations in frictional properties. Ghimire and Tanioka (2011) compiled focal mechanisms of earthquakes on the Pacific Plate off the south-east of Hokkaido and found a spatial correlation to source areas of historical earthquakes. They pointed out that the angle between the maximum principal stress direction and the fault normal was between 30° and 45° in coseismic source areas of historical earthquakes, whereas it was larger than 45° in other areas, suggesting that the coseismic areas of historical earthquakes have larger frictional coefficients or higher shear strengths. Azuma et al. (2012) conducted an experiment using air guns and ocean bottom seismometers off the south-east coast of Hokkaido and investigated the reflectivity on the interface of the Pacific Plate. They reported that the reflectivity had lateral heterogeneity, suggesting the lateral variation of the coupling rate and frictional properties on the plate interface.

As many moderate-sized earthquakes have been taking place on the subducting Pacific Plate off the south-east of Hokkaido, Japan, they provide a good opportunity for investigating the spatio-temporal distribution of their stress drops and its implication with respect to the frictional properties of the plate interface. In this study, we analyzed stress drops of these moderate-sized earthquakes and investigated the correlation of their spatial pattern with slip distributions of large historical earthquakes. The significance of stress drop analysis is summarized in the next section.

Stress drop and its mechanical significance

Stress drop is an important source parameter indicating the difference between the initial and residual stress levels, that is, the shear stresses before and after earthquake rupture. Stress drops of small and large earthquakes have been investigated and have almost confirmed the self-similarity of earthquakes (e.g., Kanamori and Anderson 1975; Abercrombie 1995; Prieto et al. 2004; Yamada et al. 2007; Yoshimitsu et al. 2014). This self-similarity is important in that we can treat stress drops of earthquakes as indicators of the difference between the shear strength and the dynamic stress level on the fault plane, independent of the earthquake size. Here, we must note that the self-similarity for a broad range of earthquake sizes is not fully confirmed and remains a matter of debate. Some papers have pointed out that earthquakes might have a weak dissimilarity (e.g., Mayeda et al. 2005). However, moderate-sized earthquakes with a narrow magnitude range, as considered herein, do not show a strong dissimilarity and their stress drops can be treated as an indicator of frictional characteristics.

The spatio-temporal heterogeneity of stress and strength has been investigated by stress drops of earthquakes, especially over the last several years. Allmann and Shearer (2007) analyzed stress drops of small earthquakes near Parkfield, California, and investigated the relationships between their spatial and temporal variations and the source area of the 2004 Parkfield earthquake. They concluded that earthquakes around the source area of the 2004 Parkfield earthquake had larger values of stress drop compared to the values of earthquakes outside the region. On an even finer scale, Yamada et al. (2010) investigated stress drops of small earthquakes that occurred on the fault plane of the 2006 Kīholo Bay earthquake (M W 6.7) and compared the values of stress drop to the slip distribution of the earthquake. They found that small earthquakes around large slip patches of the main shock were likely to have larger values of stress drop. They concluded that the spatial pattern of stress drop reflects coherent variations in the difference between the strength and the residual stress level. Urano et al. (2015) conducted a similar analysis of the 2007 Noto Hanto earthquake and concluded that static stress drops of aftershocks in a large slip area of the mainshock are larger than those in a small slip area. This result also suggests that stress drops of earthquakes reflect in situ frictional properties, which is the same as the conclusion of Yamada et al. (2010). Oth (2013) estimated stress drops of earthquakes in Japan and concluded that the values were strongly correlated with heat flow variations. He also pointed out that the lateral stress drop variations of subcrustal earthquakes with a focal depth larger than 30 km were likely to be consistent with the coupling properties of the plate interface. Uchide et al. (2014) analyzed stress drops of 1563 small earthquakes of M3.0-M4.5 in the area east of the Tohoku region that occurred before the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake and found lateral variations in stress drop along the strike. Yamada et al. (2015) analyzed a cluster of earthquake activity beneath the Tanzawa Mountains, Japan. They found that the activity included earthquakes with a small stress drop and showed the hypocenter migration. They concluded that the activity would be triggered by the increase of pore pressure due to fluid, that is, the decrease of the shear strength. Although stress drop estimates generally include some assumptions, such as circular faults explained in the next section, these previous studies strongly suggest that the values of stress drop reflect actual physical characteristics of the fault planes of earthquakes.

On the other hand, some studies raised questions as to whether the estimated stress drop reflects frictional properties. Shearer et al. (2006) investigated stress drops of aftershocks of the 1992 Landers earthquake and compared their spatial pattern to coseismic displacements on three major segments derived by Wald and Heaton (1994). They pointed out that stress drops of aftershocks on the northern segment (Camp Rock/Emerson faults) were consistent with the slip distribution. However, they also found that the values on the southern segment (Landers/Johnson Valley faults) showed a weaker correlation and were anti-correlated on the central segment (Homestead Valley fault). Hardebeck and Aron (2009) analyzed stress drops of earthquakes on the Hayward fault. They found that stress drops had a good correlation with an applied shear stress but did not directly correlate with the proposed strength of the wall-rock geology. They pointed out that this suggests the stress drop gives information on the fault strength, but the relation between the fault strength and the strength of wall rock would be complex. Our result will provide an example of whether or not stress drops derived from seismograms can be used for investigating frictional properties on earthquake faults.

Methods/Experimental

We analyzed stress drops of 686 earthquakes with 4.0 ≤ M ≤ 5.0 off the south-east of Hokkaido, Japan, that took place from June 2002 to December 2015 (Fig. 1). Note that, in this paper, M expresses the magnitude of an earthquake as determined by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA). The hypocenters of the 686 earthquakes were located from 40.5° N to 43.5° N in latitude and from 141.0° E to 146.5° E in longitude with a depth of ±15 km from the interface of the Pacific Plate deduced by Kita et al. (2010). The distance of 15 km in depth direction is within the range of uncertainty in the hypocenter determination in the study area because of the poor azimuthal coverage of seismic stations. We used waveforms observed at stations maintained by National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Resilience, Japan (NIED), Hokkaido University, and JMA.

a Seismicity in the study region from 2002 to 2015. Hypocenters with M greater than or equal to 3.0, as determined by JMA, are plotted. The color and size of the symbols indicate the depth and magnitude of earthquakes, respectively. We can clearly see that most earthquakes occur on the subduction interface of the Pacific Plate. b Hypocenters of analyzed earthquakes and seismic stations used in this study. The red circles indicate hypocenters, and the blue squares indicate seismic stations, including stations of Hi-net (NIED), JMA, and Hokkaido University. The orange lines indicate the depth of the upper surface of the subducting Pacific Plate (Kita et al. 2010) at intervals of 20 km. Waveforms observed at the station N.TKIH are shown in Figs. 2 and 3 as examples

An observed waveform as a function of time W(t) includes the effects of the source S(t), the path from a hypocenter to a receiver P(t), site amplification effects St(t), and the instrumental features of a seismometer I(t), that is:

where ∗ denotes convolution. In the frequency domain, the convolution can be expressed as a scalar product, and the following equation holds:

where W(f), S(f), P(f), St(f), and I(f) are expressions in the frequency domain of W(t), S(t), P(t), St(t), and I(t), respectively. If we know the expressions of P(f), St(f), and I(f), we can calculate the Green’s function and estimate the source effect from the observed waveform. As it is actually difficult to estimate the Green’s function precisely, we used the method of empirical Green’s function (EGF) (e.g., Hartzell 1978).

The observed waveforms of two earthquakes at a station can be expressed as follows:

If the hypocenters of the two earthquakes are identical, no velocity change takes place during the two earthquakes, and the soil beneath the station acts linearly independent of the amplitude of the incoming waveforms, then the path and site effects are exactly the same, P 1(f) = P 2(f) and St 1(f) = St 2(f). In this case, we can extract the ratio of the source effect by calculating the ratio of the observed waveforms in the frequency domain,

Equation (5) gives the spectral ratio of each pair of an analyzed earthquake and an EGF earthquake. We assume that source spectrum of an earthquake S C(f) can be expressed by the omega-squared model of Boatwright (1978), which is shown as the following equation:

where R, M 0, and f 0 are the coefficient of the radiation pattern, the seismic moment, and the corner frequency of the earthquake, respectively. Here, C indicates the wave type, which is either P or S. This assumption means that we approximated the fault plane as a circular plane. The deconvolved velocity amplitude spectra \( \left|{\dot{u}}_r^C(f)\right| \) can then be expressed as follows:

where subscripts A and E indicate analyzed and EGF earthquakes, respectively. Moreover, \( {R}_r^C \) and M 0r express the relative values of \( {R}_A^C/{R}_E^C \) and M 0A /M 0E , respectively. The value of \( {R}_r^C \) is equal to 1 if the focal mechanisms and hypocenters of the analyzed and EGF earthquakes are exactly the same. The sampling rate of waveforms analyzed in the present study was 100 Hz. We used waveforms of earthquakes in 2004 through 2015 with M3.5 that were closest to the hypocenters of the analyzed earthquakes as EGFs. A list of analyzed and EGF earthquakes is available as an Additional file 1 (see eqlist.txt).

We selected earthquakes with M3.5 as EGFs and analyzed earthquakes in a relatively narrow magnitude range of 4.0 ≤ M ≤ 5.0 based on the following considerations. In order to ensure a good signal-to-noise ratio of EGFs, especially for spectra of lower frequencies, we selected earthquakes with M3.5 as EGFs. The lower limit (M4.0) of the analyzed earthquakes was fixed in order to maintain a difference in magnitude of 0.5 compared to the EGFs and to ensure quality in estimating the corner frequencies. As stress drops are estimated for individual earthquakes, the values for large earthquakes would represent the average characteristics of individual large fault planes and would not reflect local frictional characteristics. In addition, as waveforms of some large earthquakes were clipped, we set the upper limit of the earthquake size to M5.0.

We calculated the spectral ratios of P and S waves for individual pairs of an earthquake and an EGF. The spectral ratios were calculated for three time windows with a length of 10.23 s, or 1024 data points. The start times of the first window were 0.50 s prior to the arrival times for either the P or S waves. The elapsed times of the two successive time windows were 1.28 and 2.56 s, respectively. Taking the logarithm of Eq. (7), the spectral ratio can be approximated as follows:

Before fitting each analyzed spectral ratio with the theoretical ratio expressed by Eqs. (8) and (9), we resampled the frequencies so that the interval was equal to 0.05 on a log10 scale. As a result, we obtained 20 frequency bands (data points) for each order of frequency. This procedure made it possible to treat high- and low-frequency data equally. We also calculated the standard deviation of the spectral ratio for each frequency band and used the value in fitting data, as explained below.

We estimated the values of \( {R}_r^C{M}_{0r} \), \( {f}_{0A}^C \), and \( {f}_{0E}^C \) in Eq. (9) for each station by a grid search that gave the minimum residual for the spectral ratios of three time windows, similar to Imanishi and Ellsworth (2006):

where σ i is the standard deviation for each frequency band calculated in resampling the spectral ratio. All of the earthquakes have four or more stations available for the corner frequency estimation. We used data from 0.7 to 20 Hz to calculate the residual in Eq. (10) and estimated corner frequencies by grid search between 0.3 and 20 Hz. This frequency range and the length of the time window (10.23 s) were selected so that we were able to analyze corner frequencies of earthquakes with 4.0 ≤ M ≤ 5.0, which would be around 1–3 Hz, as expected by the self-similarity of earthquakes. Figures 2 and 3 show examples of velocity waveforms, their spectra, deconvolved spectra with a resampling, and the best-fit curves of spectral ratio that were used for estimating a corner frequency. We also provide examples for another earthquake as supplemental figures (Additional files 2 and 3: Figures S1 and S2). We can see that waveforms have a signal-to-noise ratio larger than a factor of five even for low frequencies between 0.7 and 2 Hz for EGF earthquakes.

a Example of an analyzed waveform of an earthquake with M4.8. The color lines indicate the three time windows used in deconvolution, which were (P0) − 0.50 to 9.73 s, (P1) 0.78 to 11.01 s, and (P2) 2.06 to 12.29 s after the P arrival. The gray line shows a time window from 12.00 to 1.77 s before the arrival time of the P wave, which was used to calculate the spectrum of a noise in (b). Each time window has 1024 data points. b Spectra of waveforms for the four time windows shown in (a). c Example of a waveform of an M3.5 earthquake that was used for an EGF. Note that the vertical scales in (a) and (c) are different. d Spectra of waveforms for the four time windows shown in (c). e Deconvolved spectra with the fitted omega-squared model. The color lines are deconvolved source spectra, that is, (b) divided by (d), for three individual time windows with a resampling of frequency bands. The black broken line shows the fitted omega-squared model with corner frequencies of 3.98 and 12.6 Hz for the analyzed and EGF earthquakes, respectively

a Example of an analyzed waveform of an earthquake with M4.8. The color lines indicate the three time windows used in deconvolution, which were (S0) − 0.50 to 9.73 s, (S1) 0.78 to 11.01 s, and (S2) 2.06 to 12.29 s after the S arrival. The gray line shows a time window from 12.00 to 1.77 s before the arrival time of the P wave, which was used to calculate the spectrum of a noise in (b). Each time window has 1024 data points. b Spectra of waveforms for the four time windows shown in (a). c Example of a waveform of an M3.5 earthquake that was used for an EGF. Note that the vertical scales in (a) and (c) are different. d Spectra of waveforms for the four time windows shown in (c). e Deconvolved spectra with the fitted omega-squared model. The color lines are deconvolved source spectra, that is, (b) divided by (d), for three individual time windows with a resampling of frequency bands. The black broken line shows the fitted omega-squared model with corner frequencies of 3.16 and 12.6 Hz for analyzed and EGF earthquakes, respectively

Finally, we calculated the values of stress drop following Madariaga (1976):

where V S is the shear wave velocity (=4.5 km/s, from Matsubara and Obara 2011), and C indicates the wave type. We used k = 0.32 and k = 0.21 for P and S waves, respectively, assuming that the rupture speed corresponds to 0.9V S (Madariaga 1976). We will discuss the effect of the value k in the section “Discussion.” We assumed that M is equivalent to the moment magnitude M W in calculating stress drops. We also discuss the validity of this assumption in the section “Discussion.” The seismic moment M 0 in newton meters (Nm) can be calculated from M W using the following equation (Hanks and Kanamori 1979): log10 M 0 = 1.5M W + 9.1.

Results

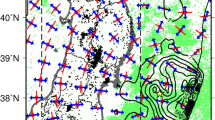

Figure 4 shows the spatial pattern of stress drop estimated from P and S waves. The results of stress drops for individual earthquakes are available as Additional files 4 and 5 (see results_P.txt and results_S.txt). The spatial patterns of stress drop for the results estimated from both P and S waves suggest correlations with slip distributions of large earthquakes and an afterslip following the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake. Earthquakes that occurred in the area with a large coseismic slip during the 1968 Tokachi-oki (M W 8.2), the 1973 Nemuro-oki (M W 7.8), and the 2003 Tokachi-oki (M W 8.0) earthquakes had large values of stress drop. On the other hand, earthquakes in the afterslip area of the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake, where lower strain was released during the sequence, showed smaller values of stress drop. These results suggest that stress drops of earthquakes represent in situ frictional properties, which is consistent with previous studies. However, we must also note that slip distributions derived by the waveform inversion may have large uncertainty (e.g., Mai et al. 2016). We summarize the results for the three areas in the following subsections. The significance of the results, as well as the discrepancy between the absolute values of stress drop estimated from P and S waves are discussed in the section “Discussion.”

a Stress drops for individual earthquakes estimated from P waves. The scale and color of circles indicate the earthquake magnitude and value of stress drop, respectively. The thick lines indicate the depth of the upper surface of the subducting Pacific Plate (Kita et al. 2010). Thin contours A through C show coseismic displacements for the 1968 Tokachi-oki (Nagai et al. 2001), 2003 Tokachi-oki (Yamanaka and Kikuchi 2003), and 1973 Nemuro-oki earthquakes (Yamanaka 2006), respectively, at intervals of 1 m. b Spatially smoothed stress drop derived from (a) at grid points at intervals of 0.1 degrees in latitude and longitude. The value at each grid point was calculated as the average of stress drops of earthquakes within 20 km of the epicentral distance from the grid point. Values were not assigned at grid points with less than four earthquakes within 20 km of the epicentral distance. c Stress drops estimated from S waves. d Map view of spatially smoothed stress drop derived from (c)

Source area of the 1968 Tokachi-oki earthquake

Figure 5a shows a magnified image of the results for the S wave in this region. The thick gray and thin black lines indicate the depths of the Pacific Plate and the coseismic slip of the 1968 Tokachi-oki earthquake, respectively (as in Fig. 4). Refer to the caption of Fig. 5 regarding the intervals of the contours. Earthquakes in an area with a coseismic slip greater than 1 m clearly had higher stress drops than earthquakes that occurred around the source area of the 1968 earthquake.

Magnified images of the three coseismic source areas shown in Fig. 4d for a the 1968 Tokachi-oki (Nagai et al. 2001), b 2003 Tokachi-oki (Yamanaka and Kikuchi 2003), and c 1973 Nemuro-oki earthquakes (Yamanaka 2006). The interval of the coseismic slip is 1 m (as in Fig. 4). The dominant area of the afterslip following the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake is indicated by a broken blue line. Please refer to Miyazaki et al. (2004, 2004) for details

We calculated the average values of stress drop in the region with a coseismic slip larger than 1 m during the 1968 earthquake and those in other regions in Fig. 5a. The values were 64.6 and 20.2 MPa, respectively, and the difference was statistically significant with a 99% confidence interval from Welch’s t test. This is consistent with the results of Yamada et al. (2010) and Urano et al. (2015), suggesting that the spatial pattern of stress drop reflects the frictional characteristics of the plate interface.

Moreover, in this region, the area with a high stress drop and a large slip during the 1968 earthquake corresponds to the kink of the subducting Pacific Plate. This may imply that the geometry of the subducting Pacific Plate plays an important role with regard to the frictional properties of the upper plate interface of the Pacific Plate.

Source area of the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake

Figure 5b shows the spatial pattern of stress drop of moderate-sized earthquakes in this region. Quantitatively investigating the correlation between the spatial distribution of stress drop values and the coseismic displacement of the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake would be difficult because few earthquakes occurred in the area with a large coseismic slip. Figure 4c indicates, however, that earthquakes in this area had larger values of stress drop, suggesting that the difference between the shear strength and the dynamic stress level is large in this area. In addition, Fig. 5b shows the correspondence between the afterslip area following the 2003 earthquake and the stress drop distribution of our results. Miyazaki et al. (2004) investigated the spatio-temporal distribution of afterslip following the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake and found that significant afterslip occurred in the adjacent areas to the south and east of the coseismic rupture area of the 2003 earthquake between the rupture areas of the 1968 Tokachi-oki and 1973 Nemuro-oki earthquakes. The afterslip area is quite consistent with the area with a smaller stress drop in this study. As the afterslip area had a smaller displacement compared to that in the coseismic area, this consistency also suggests that the spatial pattern of the frictional characteristics exhibits little temporal change and can be inferred from the stress drop analysis, supporting the conclusions of Yamada et al. (2010) and Urano et al. (2015).

However, the afterslip area of the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquakes could be also included in the coseismic area of the 1952 Tokachi-oki earthquake (e.g., Hirata et al. 2003). The spatial resolution of the slip distribution of the 1952 earthquake would be lower than that of the 2003 sequence, which implies that the frictional properties in the region might exhibit significant temporal change. Further analysis of stress drops for a longer period may provide a clue for investigating temporal changes in frictional properties.

Source area of the 1973 Nemuro-oki earthquake

It is difficult to quantitatively investigate the correlation between the values of stress drop and the coseismic displacement of large earthquakes in this region. One reason for this difficulty is that we could not estimate values of stress drop in most of the area with a large slip during the 1973 Nemuro-oki earthquake because few moderate-sized earthquakes occurred in the shallower part of the coseismic area of the 1973 earthquake from 2002 to 2015 (Figs. 1 and 4).

Earthquakes that occurred west of the source area of the 1973 Nemuro-oki earthquake had larger values of stress drop. This region corresponds to the seismic gap between the 2003 Tokachi-oki and the 1973 Nemuro-oki earthquakes and is included in the coseismic area of the 1952 Tokachi-oki earthquake with M W 8.1 (Hirata et al. 2003). If the conclusions of Yamada et al. (2010) and Urano et al. (2015) hold, our result implies that the region would have acted as a barrier to the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake and would have higher potential for strain release, suggesting that this region may experience larger displacement during the next large earthquake.

Moreover, as shown in Fig. 4, there is a low stress-drop patch around 42.7° N latitude and 145.0° E longitude. One reason for this would be that the area has a lower shear strength. This is consistent with a higher seismicity in this area, as shown in Fig. 4a, c, because the subduction rate of the Pacific Plate in this area should be the same as that for the surrounding areas.

Discussion

Physical background of the spatial pattern of stress drop

As we pointed out in the section “Stress drop and its mechanical significance,” stress drop is an important source parameter indicating the difference between the shear strength and the dynamic stress level. Although the absolute value of shear strength and the dynamic stress level cannot be constrained based on waveform analyses, it is possible to estimate the difference between the two physical quantities if there is no significant overshoot or undershoot because the initial stress should be equal to the shear strength at the hypocenter, where the rupture initiates. As each earthquake gives one value of stress drop that reflects an averaged physical characteristic over a fault plane, the following must be considered.

First, we must analyze moderate-sized or smaller earthquakes. If the analyzed earthquakes have large fault planes, the obtained values of stress drop would not reflect local physical properties, but rather averaged properties over the large fault planes. We analyzed earthquakes with 4.0 ≤ M ≤ 5.0, and their fault sizes were on the order of 1 km. In this sense, our results for stress drop can be treated as indicators of the physical properties of the Pacific Plate. Second, as mentioned in the section “Stress drop and its mechanical significance,” we must consider the self-similarity of earthquakes independent of their magnitudes. We will discuss this point in the following subsection and will confirm that our results reflect the spatial characteristics of the frictional properties of the Pacific Plate.

Stress drop as a function of depth, magnitude, and time

Figure 6a shows stress drops estimated from S waves as a function of focal depth. The red circles indicate average values of stress drop for each depth bin of every 10 km. No clear depth dependence of stress drop is observed between 10 and 80 km, suggesting that the spatial pattern in Figs. 4 and 5 cannot be explained by the variation in focal depth alone. Oth (2013) found a slight depth dependence of stress drop for all of Japan, and his result was different from ours. One reason for this may be that most inland earthquakes were excluded in our analysis. Further investigation may clarify the depth dependence of stress drop.

a Stress drops estimated from S waves as a function of focal depth. The red circles indicate average values for each depth bin for every 10 km. Vertical bars indicate standard errors for individual earthquakes, as calculated from results at individual stations and components. b Stress drops estimated from S waves as a function of magnitude. The red circles indicate average values for individual magnitude bins. Vertical bars indicate standard errors (same as (a)). c Estimated values of stress drop as a function of time

Values of stress drop as a function of magnitude are shown in Fig. 6b. The red circles indicate average values of stress drop for individual magnitude bins. Although no significant dependence of stress drop on magnitude was observed, there may be a weak correlation. Smaller earthquakes appear to have smaller values of stress drop. One possible reason for this is that the smallest value of stress drop can be controlled by the lowest available frequency, or the length of the time window, as explained in Fig. 3. Regardless of whether this is an artifact, this slight dependency of stress drop on the earthquake size can cause an apparent spatial distribution of stress drop. We confirmed that the earthquakes had no spatial heterogeneity in size and that the observed spatial pattern of stress drop was not an artifact. Figure 6c shows the estimated stress drops as a function of time from June 2002 to December 2015. There is no apparent temporal change with respect to stress drop.

We would like to emphasize that no significant dependence of stress drop on depth or earthquake size was observed in our study. We found no temporal change. This is very important because we can rule out the possibility that the spatial pattern obtained in Fig. 4 is due to depth dependence of the estimated stress drop, temporal heterogeneity of earthquake occurrence, or size dependence of the stress drop. Moreover, this confirms that the spatial pattern of stress drop shown in Figs. 4 and 5 reflects the spatial heterogeneity of the frictional properties of the Pacific Plate.

Values of stress drop estimated from P and S waves

As each earthquake has one value of stress drop, the value of stress drop for an earthquake estimated from P wave should be equal to the value estimated from S wave. Note, however, that the absolute values of stress drop estimated from P waves are much smaller than the values deduced from S waves in this study (Fig. 4). This discrepancy originates from the assumed rupture speed in the model and hence provides an insight into the rupture characteristics of analyzed moderate-sized earthquakes, as described in detail in the following.

The model of Madariaga (1976) assumes that the rupture initiates from the center of a fault plane and propagates with a certain speed that is lower than the P-wave velocity. The values of 0.32 and 0.21 for constant k in Eq. (11) depend on the assumed rupture speed, which we assumed to be 90% of the S-wave velocity V S . These factors become smaller for a lower rupture speed, and the value of k for P wave is much more sensitive to the rupture speed than that for S wave (Madariaga 1976). As the estimated values of stress drop from P waves in our study are smaller those from S waves, lower rupture speeds result in the values of stress drop being closer. In other words, our results suggest that the actual rupture speed of the analyzed earthquakes would be lower than 0.9V S . This is consistent with previous studies that reported the rupture speed of earthquakes to be 70–80% of V S , independent of earthquake magnitude (Wald and Heaton 1994, Yamada et al. 2005), with a few exceptions, such as the 1999 Hector Mine earthquake, which had a low rupture speed (Ji et al. 2002), and some super-shear earthquakes, including the 1999 Izmit earthquake (Sekiguchi and Iwata 2002) and the 2001 Kunlun earthquake (Walker and Shearer 2009).

The estimated values of stress drop from P waves in Fig. 4b show exactly the same lateral pattern as the estimated values from S waves in Fig. 4d. This strongly suggests that our results for stress drop are stably estimated and that their lateral pattern indicates the spatial heterogeneity of the frictional properties of the Pacific Plate.

Validity of the assumption of M = M W

We calculated stress drops under the assumption that the value of M determined by JMA is equal to M W . As this assumption might introduce an artifact in our result, we investigated its validity. Figure 7 shows the relationship between M and values of \( 3.5+\left(2/3\right){\log}_{10}\left({R}_r^C{M}_{0r}\right) \) in Eq. (7) for individual earthquakes, which correspond to moment magnitudes of analyzed earthquakes if their focal mechanisms are identical for individual earthquake pairs and moment magnitudes of EGF earthquakes with M3.5 are 3.5 (M3.5 = M W 3.5). We herein refer to the abovementioned values as apparent magnitudes. As we used earthquakes with M3.5 as EGFs, Fig. 7 suggests that M W values would be slightly smaller than M values. This implies that the absolute values of stress drop obtained in this study might be overestimated. However, we can see a clear linear relationship between the two parameters with a slope of 1. This strongly suggests that the spatial pattern in stress drop derived in this study is reliable.

Relationships of magnitudes determined by JMA and the apparent magnitude derived as the sum of the magnitude of EGF earthquakes (3.5) and values of \( \left(2/3\right){\mathit{\log}}_{10}\left({R}_r^C{M}_{0r}\right) \) in Eq. (7), which corresponds to the difference in magnitude between the analyzed and EGF earthquakes if their focal mechanisms are identical. a and b show the results for P and S waves, respectively

Conclusions

We analyzed stress drops of 686 earthquakes with magnitudes of 4.0 to 5.0 off the south-east of Hokkaido, Japan, and investigated the spatial heterogeneity of the difference between the shear strength and the dynamic stress level on the Pacific Plate. Spatial patterns of stress drop for both results estimated from P and S waves suggest correlations with slip distributions of large historical earthquakes and an afterslip following the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake. This suggests that the frictional properties of the plate interface exhibit little temporal change and their spatial pattern can be monitored by stress drops of moderate-sized earthquakes. The spatial heterogeneity can be used in estimating the slip pattern of a future large earthquake and discussing a policy for disaster mitigation, especially for regions in which slip patterns of historical large earthquakes are unclear, including the western coast of North America.

References

Abercrombie RE (1995) Earthquake source scaling relationships from −1 to 5 M L using seismograms recorded at 2.5-km depth. J Geophys Res 100:24015–24036

Allmann BP, Shearer PM (2007) Spatial and temporal stress drop variations in small earthquakes near Parkfield, California. J Geophys Res 112:B04305. doi:10.1029/2006JB004395

Azuma R, Murai Y, Katsumata K, Nishimura Y, Yamada T, Mochizuki K, Shinohara M (2012) Was the 1952 Tokachi-oki earthquake (M W = 8.1) a typical underthrust earthquake?: plate interface reflectivity measurement by an air gun-ocean bottom seismometer experiment in the Kuril Trench. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 13:Q08015. doi:10.1029/2012GC004135

Boatwright J (1978) Detailed spectral analysis of two small New York State earthquakes. Bull Seismol Soc Am 68:1131–1177

DeMets CR, Gordon R, Argus D, Stein S (1990) Current plate motion. Geophys J Int 101:425–478

Ghimire S, Tanioka Y (2011) Spatial distribution of stress and frictional strength along the interplate boundary in northern Japan and its correlation to the locations of large earthquakes. Techtonophys 511:1–13. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2011.08.004

Hanks TC, Kanamori H (1979) A moment magnitude scale. J Geophys Res 84(B5):2348–2350

Hardebeck JL, Aron A (2009) Earthquake stress drops and inferred fault strength on the Hayward fault, East San Francisco Bay, California. Bull Seismol Soc Am 99:1801–1814. doi:10.1785/0120080242

Hartzell SH (1978) Earthquake aftershocks as Green’s functions. Bull Seismol Soc Am 68(5):1–4

Hirata K, Geist EL, Satake K, Tanioka Y, Yamaki S (2003) Slip distribution of the 1952 Tokachi-Oki earthquake (M 8.1) along the Kuril Trench deduced from tsunami waveform inversion. J Geophys Res 108:2196. doi:10.1029/2002JB001976

Imanishi K, Ellsworth WL (2006) Source scaling relationships of microearthquakes at Parkfield, CA, determined using the SAFOD pilot hole seismic array. In: Abercrombie RE, McGarr A, Kanamori H, Di Toro G (eds) Earthquakes: radiated energy and the physics of earthquake faulting, vol 170, Geophys Monogr Ser. AGU, Washington D.C, pp 81–90

Ji C, Wald DJ, Helmberger DV (2002) Source description of the 1999 Hector Mine, California, earthquake, part II: complexity of slip history. Bull Seismol Soc Am 92(4):1208–1226

Kanamori H, Anderson DL (1975) Theoretical basis of some empirical relations in seismology. Bull Seismol Soc Am 65:1073–1095

Kita S, Okada T, Hasegawa A, Nakajima J, Matsuzawa T (2010) Anomalous deepening of a seismic belt in the upper-plane of the double seismic zone in the Pacific slab beneath the Hokkaido corner: possible evidence for thermal shielding caused by subducted forearc crust materials. Earth Planet Sci Lett 290:415–426

Madariaga R (1976) Dynamics of an expanding circular fault. Bull Seismol Soc Am 66:639–666

Mai PM, Schorlemmer D, Page M, Ampuero JP, Asano K, Causse M, Custodio S, Fan W, Festa G, Galis M, Gallovic F, Imperatori W, Käser M, Malytskyy D, Okuwaki R, Pollitz F, Passone L, Razafindrakoto HNT, Sekiguchi H, Song SG, Somala SN, Thingbaijam KKS, Twardzik C, van Driel M, Vyas JC, Wang R, Yagi Y, Zielke O (2016) The earthquake-source inversion validation (SIV) project. Seismol Res Lett 87:690–708. doi:10.1785/0220150231

Matsubara M, Obara K (2011) The 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku earthquake related to a strong velocity gradient with the Pacific plate. Earth Planets Space 63:663–667

Mayeda K, Gök R, Walter WR, Hofstetter A (2005) Evidence for non-constant energy/moment scaling from coda-derived source spectra. Geophys Res Lett 32:L10306. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL022405

Miyazaki S, Larson KM, Choi K, Hikima K, Koketsu K, Bodin P, Jaase J, Emore G, Yamagiwa A (2004) Modeling the rupture process of the 2003 September 25 Tokachi-Oki (Hokkaido) earthquake using 1-Hz GPS data. Geophys Res Lett 31:L21603. doi:10.1029/2004GL021457

Miyazaki S, Segall P, Fukuda J, Kato T (2004) Space time distribution of afterslip following the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake: implications for variations in fault zone frictional properties. Geophys Res Lett 31:L06623. doi:10.1029/2003GL019410

Nagai R, Kikuchi M, Yamanaka Y (2001) Comparative study on the source processes of recurrent large earthquakes in Sanriku-oki region: the 1968 Tokachi-oki earthquake and the 1994 Sanriku-oki earthquake. Zisin ser.2 54:267–280 (in Japanese with English abstract)

Oth A (2013) On the characteristics of earthquake stress release variations in Japan. Earth Planet Sci Lett 377–378:132–141. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2013.06.037

Prieto GA, Shearer PM, Vemon FL, Klib D (2004) Earthquake source scaling and self-similarity estimation from stacking P and S spectra. J Geophys Res 109:B08310. doi:10.1029/2004JB003084

Sekiguchi H, Iwata T (2002) Rupture process of the 1999 Kocaeli, Turkey, earthquake estimated from strong-motion waveforms. Bull Seismol Soc Am 92(1):300–311

Shearer PM, Prieto GA, Hauksson E (2006) Comprehensive analysis of earthquake source spectra in Southern California. J Geophys Res 111:B06303. doi:10.1029/2005JB003979

Uchide T, Shearer PM, Imanishi K (2014) Stress drop variations among small earthquakes before the 2011 Tohoku-oki, Japan, earthquake and implications for the main shock. J Geophys Res 119:7164–7174. doi:10.1002/2014JB010943

Urano S, Hiramatsu Y, Yamada T, The Group for the Joint Aftershocks Observations of the 2007 Noto Hanto Earthquake (2015) Relationship between coseismic slip and static stress drop of similar aftershocks of the 2007 Noto Hanto earthquake. Earth Planets Space 67:101. doi:10.1186/s40623-015-0277-0

Wald DJ, Heaton TH (1994) Spatial and temporal distribution of slip for the 1992 Landers, California, earthquake. Bull Seismol Soc Am 84:668–691

Walker KT, Shearer PM (2009) Illuminating the near-sonic rupture velocities of the intracontinental Kokoxili M W 7.8 and Denali fault M W 7.9 strike-slip earthquakes with global P wave back projection imaging. J Geophys Res 114:B02304. doi:10.1029/2008JB005738

Wessel P, Smith W (1991) Free software helps map and display data. EOS Trans AGU 72(441):445–446

Yagi Y (2004) Source rupture process of the 2003 Tokachi-oki earthquake determined by joint inversion of teleseismic body wave and strong ground motion data. Earth Planets Space 56:311–316

Yamada T, Mori JJ, Ide S, Abercrombie RE, Kawakata H, Nakatani M, Iio Y, Ogasawara H (2007) Stress drops and radiated seismic energies of microearthquakes in a South African gold mine. J Geophys Res 112:B03305. doi:10.1029/2006JB004553

Yamada T, Mori JJ, Ide S, Kawakata H, Iio Y, Ogasawara H (2005) Radiation efficiency and apparent stress of small earthquakes in a South African gold mine. J Geophys Res 110:B01305. doi:10.1029/2004JB003221

Yamada T, Okubo PG, Wolfe CJ (2010) Kīholo Bay, Hawaiʻi, earthquake sequence of 2006: relationship of the main shock slip with locations and source parameters of aftershocks. J Geophys Res 115:B08304. doi:10.1029/2009JB006657

Yamada T, Yukutake Y, Terakawa T, Arai R (2015) Migration of earthquakes with a small stress drop in the Tanzawa Mountains, Japan. Earth Planets Space 67:175. doi:10.1186/s40623-015-0344-6

Yamanaka Y (2006) Asperity map in Hokkaido and southern Kurile arc. Chikyu Monthly 28:427–431 (in Japanese)

Yamanaka Y, Kikuchi M (2003) Source process of the recurrent Tokachi-oki earthquake on September 26, 2003, inferred from teleseismic body waves. Earth Planets Space 55:e21–e24

Yoshimitsu N, Kawakata H, Takahashi N (2014) Magnitude −7 level earthquakes: a new lower limit of self-similarity in seismic scaling relationships. Geophys Res Lett 41:4495–4502. doi:10.1002/2014GL060306

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express our sincere thanks to the two reviewers (Adrien Oth and an anonymous reviewer), and the editor, Yuji Yagi, for their insightful comments and suggestions, which helped us improve our manuscript. We are grateful to Rachel Abercrombie and Takahiko Uchide for their comments on a draft of this manuscript. We used waveforms from stations of Hi-net (NIED) as well as Hokkaido Univ. and JMA. The authors would like to thank the individuals maintaining these seismic stations. We also used arrival times of P and S waves as determined by JMA. The authors would also like to thank Yoshiko Yamanaka for providing the results of coseismic displacements. Figures were created using Genetic Mapping Tool software (Wessel and Smith 1991). This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan under its Earthquake and Volcano Hazards Observation and Research Program.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan, under its Earthquake and Volcano Hazards Observation and Research Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TY designed the research project, carried out the analysis, and wrote the manuscript. YS conducted preliminary analyses. YT and JK participated in the discussion of the results. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

eqlist. (TXT 65 kb)

Additional file 2: Figure S1.

(a) Example of an analyzed P waveform of an earthquake with M4.0 (UD component at station N.SKSH). The color and gray lines indicate the time windows for calculating spectra (as in Fig. 2). (b) Spectra of waveforms for the four time windows shown in (a). (c) Example of a waveform of an M3.5 earthquake that was used for an EGF. Note that the vertical scales in (a) and (c) are different. (d) Spectra of waveforms for the four time windows shown in (c). (e) Deconvolved spectra with the fitted omega-squared model. The black broken line shows the fitted omega-squared model with corner frequencies of 1.58 and 2.51 Hz for the analyzed and EGF earthquakes, respectively. (EPS 3193 kb)

Additional file 3: Figure S2.

(a) Example of an analyzed S waveform of an earthquake with M4.0 (NS component at station N.SKSH). The color and gray lines indicate the time windows for calculating spectra (as in Fig. 2). (b) Spectra of waveforms for the four time windows shown in (a). (c) Example of a waveform of an M3.5 earthquake that was used for an EGF. Note that the vertical scales in (a) and (c) are different. (d) Spectra of waveforms for the four time windows shown in (c). (e) Deconvolved spectra with the fitted omega-squared model. The black broken line shows the fitted omega-squared model with corner frequencies of 2.00 and 3.98 Hz for the analyzed and EGF earthquakes, respectively. (EPS 3181 kb)

Additional file 4:

results_P. (TXT 54 kb)

Additional file 5:

results_S. (TXT 54 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamada, T., Saito, Y., Tanioka, Y. et al. Spatial pattern in stress drops of moderate-sized earthquakes on the Pacific Plate off the south-east of Hokkaido, Japan: implications for the heterogeneity of frictional properties. Prog Earth Planet Sci 4, 38 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-017-0152-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-017-0152-7