Abstract

Background

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) circuits have been shown to sequester circulating blood compounds such as drugs based on their physicochemical properties. This study aimed to describe the disposition of macro- and micronutrients in simulated ECMO circuits.

Methods

Following baseline sampling, known quantities of macro- and micronutrients were injected post oxygenator into ex vivo ECMO circuits primed with the fresh human whole blood and maintained under standard physiologic conditions. Serial blood samples were then obtained at 1, 30 and 60 min and at 6, 12 and 24 h after the addition of nutrients, to measure the concentrations of study compounds using validated assays.

Results

Twenty-one samples were tested for thirty-one nutrient compounds. There were significant reductions (p < 0.05) in circuit concentrations of some amino acids [alanine (10%), arginine (95%), cysteine (14%), glutamine (25%) and isoleucine (7%)], vitamins [A (42%) and E (6%)] and glucose (42%) over 24 h. Significant increases in circuit concentrations (p < 0.05) were observed over time for many amino acids, zinc and vitamin C. There were no significant reductions in total proteins, triglycerides, total cholesterol, selenium, copper, manganese and vitamin D concentrations within the ECMO circuit over a 24-h period. No clear correlation could be established between physicochemical properties and circuit behaviour of tested nutrients.

Conclusions

Significant alterations in macro- and micronutrient concentrations were observed in this single-dose ex vivo circuit study. Most significantly, there is potential for circuit loss of essential amino acid isoleucine and lipid soluble vitamins (A and E) in the ECMO circuit, and the mechanisms for this need further exploration. While the reductions in glucose concentrations and an increase in other macro- and micronutrient concentrations probably reflect cellular metabolism and breakdown, the decrement in arginine and glutamine concentrations may be attributed to their enzymatic conversion to ornithine and glutamate, respectively. While the results are generally reassuring from a macronutrient perspective, prospective studies in clinical subjects are indicated to further evaluate the influence of ECMO circuit on micronutrient concentrations and clinical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is increasingly being utilized as a viable supportive treatment modality for acute severe refractory cardiorespiratory failure [1]-[3]. It can be used short term where recovery of the lungs or heart is anticipated, or as a bridge to long-term mechanical cardiac support or lung transplantation. Patients supported on ECMO are not only critically unwell but are often at cross roads while they await organ recovery or further definitive therapy [1]. Despite controversies [4] around what constitutes optimal nutritional support in an intensive care unit (ICU), preserving nutritional status and overall physical condition is an important aspect of their management [5].

There is growing evidence that malnutrition in the critically ill influences morbidity and mortality [6]-[8]. Patients may receive ECMO support for weeks or may have had chronic disease which impacts their nutritional status pre-morbidly. Available data indicates that feed intolerance may occur in up to 38% of the ECMO patients [5] and that patients may be receiving as little as 50% of their nutritional requirements due to enteral feed intolerance [9] resulting in large caloric deficit. In this setting, sequestration if any of vital nutrients in ECMO circuits may lead to further nutritional debilitation.

The ECMO circuit is not, however, a passive conduit for the blood and may sequester a variety of circulating compounds such as drugs [10]-[12] and possibly nutrients, effectively reducing the bioavailability of these compounds. Other ex vivo studies in cardiopulmonary bypass circuits have demonstrated that these circuits can sequester trace elements [13]. Hence, it is therefore plausible that there may be clinically relevant interactions between the ECMO circuit and macro-/micronutrients. However, to date, there is no data pertaining to nutrient disposition in the ECMO circuit.

The aim of this 24-h single-dose study was to identify any significant reduction in circulating concentrations of macronutrients (glucose, amino acids and fatty acids) or micronutrients (fat soluble vitamins, water soluble vitamins, selenium, copper, zinc and manganese) in an ex vivo ECMO circuit model primed with the fresh human whole blood.

Methods

Ethics approval was obtained from the local Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/12/QPCH/90).

ECMO circuits

The methods for the development of the ex vivo model of ECMO used in the experiment have been published previously [14]. Briefly, three new ECMO circuits were used (Maquet Cardiopulmonary AG, Hechinger Strabe, Germany). Each circuit had an identical composition: Bioline tubing, a PLS Quadrox D oxygenator and a Rotaflow pump head. A reservoir bladder (R-38; Medtronic Pty Ltd., Minneapolis, MN, USA) was added to contribute compliance to the system and thus, allow blood sampling from a closed circuit. The three circuits were initially primed with 0.9% saline (Baxter Healthcare, Toongabbie, NSW, Australia). Five thousand international units of Porcine mucous heparin (Pfizer Pty Ltd., Perth, Australia) was added to the circuits. The fresh human whole blood (6 days old) was then added to the circuit in exchange for the saline prime. Circuits were volume pressurized to obtain post-oxygenator pressures of 230 to 250 mmHg.

The final volume of the pressurized circuit was 819 ± 82 mL with a mean haemoglobin value of 70 ± 2 g/L. Oxygen tension in the circuit blood was maintained between 150 to 200 mmHg (mean 175 ± 8 mmHg). Circuit temperature was maintained at 37°C. The pH of the circulating blood was maintained in the range of 7.25 to 7.55 by use of carbon dioxide gas or sodium bicarbonate solution added to the circuit. The pH, pO2, pCO2, potassium and lactate were checked at baseline, 6 h and at the conclusion of the experiment (24 h) to ensure consistency between all three circuits. Flow rates in each circuit were maintained at 4 to 5 L/min. Ambient temperature and light conditions were identical for all three circuits during the experiment.

Preparation and injection of nutrient solutions

Standard parenteral nutrition (PN) solution was prepared from a ready-to-mix triple phase bag containing amino acids, glucose, lipids and electrolytes (4QH.01TC, Baxter Healthcare, Toongabbie, NSW, Australia) as per manufacturer's recommendations. One dose each of trace element solution (10 mL Baxter MTEFE) and vitamin powder (Baxter Cernevit reconstituted in 5 mL water) was added to the PN bag through a sterile port. Each PN bag was agitated for 3 min to ensure thorough distribution of contents while being covered by a light impermeable bag provided by the manufacturer. After reconstitution, 10 mL of this solution was extracted in a clean 10-mL syringe and then injected into the ex vivo circuit at the post-oxygenator site. This dose was selected to emulate typical concentrations observed in an ECMO patient receiving total PN (70 mL/h of 3:1 TPN premix solution) over a 24-h period. This was necessary to exclude any concentration-dependent sequestration.

Blood sample collection and nutrient assays

A 3-min period of equilibration was allowed for each circuit at a flow rate of 4 L/min prior to injection of PN solution. Blood samples (10 mL each) were collected from each circuit from the post-oxygenator site at time-points: baseline (after equilibration), 1 min (after addition of PN), 30 and 60 min and 6, 12 and 24 h. Figure 1 details the collection of samples using light protective precautions to prevent photodegradation. Samples were analysed using nutrient assays as outlined in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

We used a mixed model with a random intercept for each circuit to control for the nonindependence of results from the same circuit. The nutrient concentrations in samples drawn at 1-min interval following the injection of PN solution into the circuit were included in the model as a baseline. The key predictor variable was time in hours which we assumed to be linear. All analyses were made using R version 3.0.2. This model accounts for the repeated responses from the same circuit using a random intercept. The concentration of nutrient versus time curves (mean ± SEM) were plotted using GraphPad Prism Version 5.03.

Results

There were no circuit complications. There were no significant differences between oxygen or carbon dioxide tensions, pH, temperature, electrolyte composition and degree of hemolysis between circuits. Circuit parameters are described in Table 2.

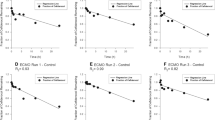

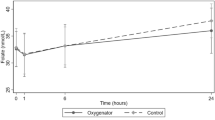

Twenty-one samples were analysed for thirty-one nutrient compounds. Linear changes in hourly nutrient concentrations in the ECMO circuit are presented in Table 3. The 95% CIs for mean hourly changes for a majority of nutrients indicate minimal variability in nutrient concentrations between circuits. Concentration versus time curves for the test compounds are graphed in Figures 2,3,4. There were significant reductions (p < 0.05) in circuit concentrations of some amino acids [alanine (10%), arginine (95%), cysteine (14%), glutamine (25%) and isoleucine (7%)], vitamins [A (42%) and E (6%)] and glucose (42%) over 24 h. Significant increases in circuit concentrations (p < 0.05) were observed over time for most amino acids, zinc and vitamin C. There were no statistically significant reductions in total proteins, triglycerides, total cholesterol, selenium, copper, manganese and vitamin D concentrations within the ECMO circuit over a 24-h period. While the reductions in glucose concentrations and an increase in other macro- and micronutrient concentrations probably reflect cellular metabolism and breakdown, the decrement in arginine and glutamine concentrations may be attributed to their enzymatic conversion to ornithine and glutamate, respectively. There was no significant correlation between physicochemical properties such as molecular weight, polarity and solubility on circuit disposition.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study represents the first investigation of macro- and micronutrient disposition in ex vivo ECMO circuits. Significant alterations in macro- and micronutrient concentrations were observed in this study. Most significantly, there is potential for circuit loss of essential amino acid isoleucine and lipid soluble vitamins (A and E) in the ECMO circuit, and the mechanisms for this need further exploration. While the results are generally reassuring from a macronutrient perspective, prospective studies in clinical subjects are indicated to further evaluate the influence of ECMO circuit on micronutrient concentrations and clinical outcomes.

The findings of this preliminary study that identifies nutrients that risk being lost in ECMO circuits are significant for the following reasons. In the absence of circuit sequestration of most macro- and micronutrients, it can be assumed that the nutrient bioavailability from enteral feeds should be almost entirely related to feed tolerance and absorption and clinicians can focus on improving either of these as feasible. Equally, when feed intolerance is intractable, PN in standard doses may be a viable option. Most importantly, identifying the macro- and micronutrients that are most affected by the addition of an extracorporeal circuit to a critically ill patient may allow better nutritional surveillance and/or supplementation as appropriate. While the tested nutrients play an important role in health and disease, it is unlikely that the adverse clinical outcomes if any of circuit nutrient loss and benefits if any of supplementing at risk nutrients will ever be tested in a randomised trial design and is probably not of sufficient priority. However, minimising the biological burden from mechanical assist device therapy has the potential to improve patient outcomes, and this study is one step in that direction.

Nutrient compounds possess unique physicochemical properties - size, charge and hydrophobicity vary significantly within and between each nutrient group [15]. Glucose is polar, ionic and hydrophilic; the amphipathic fatty acids possess both hydrophilic and lipophilic properties; and amino acids can be measured on a hydrophobicity index due to the varying solubilities of different amino acids in water and in varying pH conditions [15]-[17]. The majority of vitamins are hydrophilic with the exception of vitamins A, D, E and K, which are lipophilic; trace elements such as copper, manganese and zinc are positively charged cations; and selenium is a negatively charged anion [15]. No clear correlation could be established between physicochemical properties such as polarity, solubility or molecular weight and circuit behaviour of nutrients.

In this setting, interpretation of the alterations in individual nutrient concentrations is challenging as several physical, chemical, environmental and other unknown factors may be at play. The decrement in arginine and glutamine concentrations may be attributed to their enzymatic conversion to ornithine and glutamate, respectively [18]-[21]. Similarly, the decrease in glucose concentrations over time may be explained in part by cellular metabolism. The reductions in concentrations of amino acids such as cysteine, isoleucine and alanine and vitamins (A and E) may be explained by instability, degradation, circuit sequestration or oxidative mechanisms [22]. It is possible that lipophilicity of vitamins A and E may affect their circuit disposition; however, this was not a consistent trend as another lipophilic vitamin D was relatively unaffected. We also hypothesise that an increase in concentrations of many other nutrients in a closed circuit probably represents breakdown of cellular and noncellular components of the whole blood and detailed evaluation of mechanisms responsible for alterations in individual nutrient concentrations is beyond the scope of this experiment.

Regardless of the cause, the net result is that some nutrients are significantly lost in the ECMO circuit and the clinical relevance of this remains unclear. While saturation of circuit binding sites over time may partly alleviate circuit loss of nutrients, the circuit loss from other mechanisms such as chemical and physical degradations, oxidation etc. may continue over the duration of ECMO, as up to second/third of patient's cardiac output may be exteriorised every minute for gas exchange and mechanical circulatory support [23]. Even though enteral or parenteral nutritional support and endogenous synthetic/metabolic mechanisms ensure an ongoing supply of macro- and micronutrients into the blood stream during ECMO, its unclear how much of their bioavailability is affected by ongoing losses in the circuit. In addition, the circuit loss of some nutrients can further be compounded by critical illness factors [24]-[26] such as inflammation, multiple organ dysfunction, fluid shifts and capillary leaks that may further affect their bioavailability. Interestingly, this may be the fate of many circulating endogenous compounds such as hormones and many other biologically active substances which are neither monitored nor replaced during ECMO. This calls for further clinical studies to further elucidate the biological impact of the ECMO circuit on circulating nutrients.

This study has limitations. We attempted to replicate the clinical scenario ex vivo, which allowed us to specifically study the interactions between the nutrients and the ECMO circuit under physiologic conditions in the absence of patient and pathological factors. This single-dose study, however, contrasts with the clinical scenario wherein there is ongoing delivery of nutrients into the blood stream and ECMO support may be continued for days to weeks. A continuous infusion of PN solution into the fully primed, noncompliant circuit was not feasible. Although a reservoir bladder which is seldom used in adult patients may have added compliance to the circuit, it could have further confounded our results by sequestering test compounds or creating areas of stasis, both of which are undesirable. The absence of circulating drugs, other blood components and metabolites in our experiment may also influence nutrient interactions with the components of the circuit. We did not test nutrient losses in physiologic controls (fresh human whole spiked with equivalent dose of PN solution, stored at 37°C over 24 h) to measure nutrient losses if any over time, independent of the ECMO circuit which to an extent limited the interpretation of our results.

However, this study delineates the circuit behaviour of thirty-one vital nutrients and serves as a necessary first step in identifying at risk nutrients and identifies areas for further research.

Conclusions

Except for essential amino acid isoleucine and vitamins (A and E), most other macro- and micronutrients tested in this study were stable in the ECMO circuit over 24 h. Exteriorisation of large amounts of patient blood volume for ECMO is life-saving but may lead to circuit loss of vital nutrients. Critical illness may further exacerbate these circuit interactions of nutrients, and future studies should further evaluate altered nutrient disposition during ECMO and their potential impact on clinical outcomes.

Abbreviations

- ECMO:

-

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- EN:

-

enteral nutrition

- MTEFE:

-

micronutrient and trace elements with iron

- PN:

-

parenteral nutrition

- SEM:

-

standard error of the mean

- TPN:

-

total parenteral nutrition

References

Shekar K, Mullany DV, Thomson B, Ziegenfuss M, Platts DG, Fraser JF: Extracorporeal life support devices and strategies for management of acute cardiorespiratory failure in adult patients: a comprehensive review. Crti Care 2014, 18: 219. In Press 10.1186/cc13865

Brodie D, Bacchetta M: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for ARDS in adults. N Engl J Med 2011, 365: 1905–1914. 10.1056/NEJMct1103720

MacLaren G, Combes A, Bartlett RH: Contemporary extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for adult respiratory failure: life support in the new era. Intensive Care Med 2012, 38: 210–220. 10.1007/s00134-011-2439-2

Bajwa S, Gupta S: Controversies, principles and essentials of enteral and parenteral nutrition in critically ill-patients. J Med Nutr Nutraceuticals 2013, 2: 77–83. 10.4103/2278-019X.114731

Ferrie S, Herkes R, Forrest P: Nutrition support during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in adults: a retrospective audit of 86 patients. Intensive Care Med 2013, 39: 1989–1994. 10.1007/s00134-013-3053-2

Giner M, Laviano A, Meguid MM, Gleason JR: In 1995 a correlation between malnutrition and poor outcome in critically ill patients still exists. Nutrition 1996, 12: 23–29. 10.1016/0899-9007(95)00015-1

Doig GS, Heighes PT, Simpson F, Sweetman EA, Davies AR: Early enteral nutrition, provided within 24 h of injury or intensive care unit admission, significantly reduces mortality in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 2018–2027. 10.1007/s00134-009-1664-4

Alberda C, Gramlich L, Jones N, Jeejeebhoy K, Day AG, Dhaliwal R, Heyland DK: The relationship between nutritional intake and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: results of an international multicenter observational study. Intensive Care Med 2009, 35: 1728–1737. 10.1007/s00134-009-1567-4

Lukas G, Davies AR, Hilton AK, Pellegrino VA, Scheinkestel CD, Ridley E: Nutritional support in adult patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care Resusc 2010, 12: 230–234.

Shekar K, Roberts JA, McDonald CI, Fisquet S, Barnett AG, Mullany DV, Ghassabian S, Wallis SC, Fung YL, Smith MT, Fraser JF: Sequestration of drugs in the circuit may lead to therapeutic failure during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care 2012, 16: R194. 10.1186/cc11679

Shekar K, Fraser JF, Smith MT, Roberts JA: Pharmacokinetic changes in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Crit Care 2012, 27(741):e749–718.

Wildschut ED, Ahsman MJ, Allegaert K, Mathot RA, Tibboel D: Determinants of drug absorption in different ECMO circuits. Intensive Care Med 2010, 36: 2109–2116. 10.1007/s00134-010-2041-z

McDonald CI, Fung YL, Fraser JF: Antioxidant trace element reduction in an in vitro cardiopulmonary bypass circuit. ASAIO J 2012, 58: 217–222. 10.1097/MAT.0b013e31824cc856

Shekar K, Fung YL, Diab S, Mullany DV, McDonald CI, Dunster KR, Fisquet S, Platts DG, Stewart D, Wallis SC, Smith MT, Roberts JA, Fraser JF: Development of simulated and ovine models of extracorporeal life support to improve understanding of circuit-host interactions. Crit Care Resusc 2012, 14: 105–111.

Greenwood NN, Earnshaw A: Chemistry of the elements. 2nd edition. Butterworth-Heinemann, Butterworth-Heinemann ,Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 225; 1997.

Anneken DJ BS, Christoph R, Fieg G, Steinberner U, Westfechtel A (2006) “Fatty Acids” in Ullmann's encyclopedia of industrial chemistry. In: Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, doi:10.1002/14356007.a10_245.pub2

Kyte J, Doolittle RF: A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol 1982, 157(1):105–32. doi:10.1016/0022–2836(82)90515–0. PMID 7108955 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0

Pribis JP, Zhu X, Vodovotz Y, Ochoa JB: Systemic arginine depletion after a murine model of surgery or trauma. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2012, 36: 53–59. 10.1177/0148607111414579

Bernard AC, Mistry SK, Morris SM Jr, O’Brien WE, Tsuei BJ, Maley ME, Shirley LA, Kearney PA, Boulanger BR, Ochoa JB: Alterations in arginine metabolic enzymes in trauma. Shock 2001, 15: 215–219. 10.1097/00024382-200115030-00009

Welbourne T, Routh R, Yudkoff M, Nissim I: The glutamine/glutamate couplet and cellular function. News Physiol Sci 2001, 16: 157–160.

Ochoa JB, Bernard AC, O’Brien WE, Griffen MM, Maley ME, Rockich AK, Tsuei BJ, Boulanger BR, Kearney PA, Morris Jr SM Jr: Arginase I expression and activity in human mononuclear cells after injury. Ann Surg 2001, 233: 393–399. 10.1097/00000658-200103000-00014

Riaz MN, Asif M, Ali R: Stability of vitamins during extrusion. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2009, 49: 361–368. 10.1080/10408390802067290

Fraser JF, Shekar K, Diab S, Foley SR, McDonald CI, Passmore M, Simonova G, Roberts JA, Platts DG, Mullany DV, Fung YL: ECMO - the clinician's view. ISBT Sci Ser 2012, 7: 82–88. 10.1111/j.1751-2824.2012.01560.x

Hosein S, Udy AA, Lipman J: Physiological changes in the critically ill patient with sepsis. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2011, 12: 1991–1995. 10.2174/138920111798808248

Surbatovic M, Veljovic M, Jevdjic J, Popovic N, Djordjevic D, Radakovic S: Immunoinflammatory response in critically ill patients: severe sepsis and/or trauma. Mediators Inflamm 2013, 2013: 362793. 10.1155/2013/362793

Marshall JC: The multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. In Surgical treatment: evidence-based and problem-oriented. Edited by: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA. Zuckschwerdt, Munich; 2001.

Acknowledgements

This study was in part funded by a New Investigator Grant from The Prince Charles Hospital (TPCH) Foundation and the Critical Care Research Group. The Australian Red Cross Blood Service and Australian governments that fully funded the blood service for the provision of blood products and services to the Australian community. We thank the blood donors of Australia. We gratefully acknowledge the detailed assistance and expertise with the nutrient assays from Ms. Brooke Berry from Queensland Pathology Statewide Services (QPSS) at the Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital. We thank TPCH pathology staff for their facilitation of sample storage and handling. We acknowledge TPCH Critical Care Services for usage of the simulation area in the ICU for the experiments. JFF acknowledges the Queensland Health Medical Research fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KS, KE, ER and JF designed the study, obtained grant funding and ethics approval. KE, ER, CM and KS conducted the ex vivo experiment and collected blood samples. AB performed statistical analysis. KS, KE and ER analysed the data prepared the draft manuscript. All authors critically evaluated the manuscript and approved the final draft prior to submission.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Estensen, K., Shekar, K., Robins, E. et al. Macro- and micronutrient disposition in an ex vivo model of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ICMx 2, 29 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-014-0029-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-014-0029-7