Abstract

Arsenic (As) contamination is a major global environmental concern with widespread effects on health of living organisms including humans. In this review, the occurrence (sources and forms) of As representing diverse aquatic habitats ranging from groundwater to marine environment has been detailed. We have provided a mechanistic synopsis on direct or indirect effects of As on different organismal groups spanning from bacteria, algae, phytoplankton, zooplankton and higher trophic levels based on a review of large number of available literature. In particular, special emphasis has been laid on finfishes and shellfishes which are routinely consumed by humans. As part of this review, we have also provided an overview of the broadly used methods that have been employed to detect As across ecosystems and organismal groups. We also report that the use of As metabolites as an index for tracking Astot exposure in humans require more global attention. Besides, in this review we have also highlighted the need to integrate ‘omics’ based approaches, integration of third and fourth generation sequencing technologies for effective pan-geographical monitoring of human gut microbiome so as to understand effects and resulting consequences of As bioaccumulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arsenic (As) is a ubiquitous element present naturally in the earth’s crust and one among the 20 most common elements (Nordstrom 2002). It was first isolated and purified in 1250 AD and since then it is used in agriculture, electronics, drugs and metallurgical applications (Nriagu and Azcue 1990). Though the origin and distribution of As is mainly geogenic, anthropogenic activities (including mining, fossil fuels burning and pesticide application) can also lead to As contamination across various environments (Bissen and Frimmel 2003). This has become a major environmental concern at a global scale (Bissen and Frimmel 2003; Ravenscroft et al. 2009; Chung et al. 2014; Upadhyay et al. 2018; McArthur 2019; review by Shaji et al. 2021). The metalloid As is found in two forms namely, organic arsenic and inorganic arsenic (iAs), while As can be further classified into four major oxidation states namely, arsenate [As(V)], arsenite [As(III)], elemental arsenic (As0) and arsine (As0). Additionally, there are few methylated derivatives termed as ‘fish arsenic’ (arsenobetaine—AsB and arsenocholine—AsC) and arseno-sugar compounds (Table 1) which have been reported from various environments (Fig. 1 for chemical structures) (Ng 2005). Other than that, arsenic is naturally found in more than 200 different mineral forms, of which ca. 60% are arsenates, 20% sulfides and sulfosalts and the rest are arsenides, arsenates, oxides, silicates and elemental arsenic (Mandal and Suzuki 2002).

Naturally iAs is easily dissolved and mobilized and hence is more toxic than organic As and reported in varying concentrations from terrestrial and aquatic environments including associated biota (Shrivastava et al. 2015). Higher concentration of As is found in igneous/argillaceous sedimentary rocks (0–143 mg/kg) while marine sediment might contain up to 3000 mg/kg, which can co-precipitate with iron hydroxides and sulphides in sedimentary rocks (Boyle and Jonasson 1973). Besides iron deposits, sedimentary iron ores and manganese nodules can contain arsenic in high concentration (Mandal and Suzuki 2002). Similarly terrestrial soil can have varying concentration of As ranging between 0.1 and 50 mg/kg and can also vary based on geographical settings (Colbourn et al. 1975). Higher concentration of As in soil has been reported from China (mean: 11.2 mg/kg; Wei et al. 1991), India (mean: 14.8 mg/kg; Chakraborti et al. 2001) and Bangladesh (mean: 22.1 mg/kg; Nickson et al. 2000) compared to other countries. The As concentration also vary depending on the nature of soil and higher concentration has been reported from alluvial or organic soil compared to sandy soil (Kabata-Pendias and Pendias 1984; Punshon et al. 2017).

Over the last several decades, rapid industrialization has led to increased As emission in atmosphere (particularly those from geothermal plants and non-ferrous metal smelters) (Zhang et al. 2020a, b). According to Chilvers and Peterson (1987), emission in the atmosphere from natural sources is ca. 1.5 times higher than estimated emission from human activities. Nevertheless, due to continuous emission and accumulation, both organic and inorganic As have been reported in higher concentration from aquatic environments compared to terrestrial environments (IPCS 2001). Though geogenic in source, As contamination in aquatic biological communities occurs through accumulation from lower trophic levels to higher trophic levels (e.g. flora and fauna, particularly higher in members under the Class Pisces) (Jankong et al. 2007; Grotti et al. 2008; Taleshi et al. 2014; Srivastava and Sharma 2013; Williams et al. 2014; Oliveira et al. 2017; Han et al. 2019). Such accumulation of As in aquatic flora and fauna are typically based on geographical settings such as freshwater, estuarine, transitional and marine ecosystems while the degree of accumulation and biomagnification may also vary across species (Chen and Folt 2000; Oliveira et al. 2017), in addition to their trophic status within the food web, which strongly controls exposure and As uptake routes (McGeer et al. 2003; Schäfer et al. 2015) (Table 2).

In aquatic environments, small vertebrates (e.g. Pisces) play important role as an intermediate in energy transformation from lower trophic levels (e.g. phytoplankton, benthic microalgae, macroalgae and zooplankton) to higher trophic levels (e.g. large fishes, mammals and ultimately humans). Williams et al. (2014) reported higher concentration of As in small fishes compared to other aquatic flora and fauna. However, this may not be acceptable universally because varying concentration of different organoarsenical compounds have been reported from a variety of organisms (Schaeffer et al. 2006), thereby reflecting the complexity in overall comparison.

Globally, numerous studies have looked into the available forms of As and their contamination in various environments (Smedley and Kinniburgh 2002; Bissen and Frimmel 2003; Borba et al. 2003; Ng 2005; Ghosh et al. 2015a, b; Farooq et al. 2019; review by Shaji et al. 2021) and also in organisms representing various habitats (Chen and Folt 2000; Jankong et al. 2007; Grotti et al. 2008; Taleshi et al. 2014; Williams et al. 2014). However, As contamination, effects, bioaccumulation and biomagnification are still not well established in terms of trophic levels. Based on this backdrop, the present review has two aims: (1) provide a brief overview of As distribution and contamination in different aquatic environments, and (2) discuss about the fate of arsenic at various trophic levels focusing on the marine environment.

Forms of arsenic in aquatic environment

As(III) and As(V) are major forms of As found in various types of aquatic environments and their fluxes as both inorganic [e.g. As(III) like H3AsO30, H2AsO3−, HAsO32− and AsO33−, and As(V) like H3AsO40, H2AsO−4, HAsO42− and AsO43−] and organic forms have been found to be controlled by prevailing physicochemical parameters like pH, temperature and redox potential (Meng et al. 2000). Overall As fluxes across global aquatic environments have been reported to range from < 0.1 μg/l (unpolluted water bodies) to 5000 μg/l (areas of sulphide mineralization and mining) (Mandal and Suzuki 2002; Smedley and Kinniburgh 2002).

Groundwater

Arsenic contamination and their effects have been frequently noticed in groundwater aquifers across countries such as Canada, United States of America (USA), Mexico, Chile, Argentina, Spain, Italy, Hungary, Poland, Finland, India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Thailand, Burma, China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Taiwan, Japan, Australia and New Zealand (Valette-Silver et al. 1999; Argos et al. 2010; Shaji et al. 2021). There are three main sources of As contamination in groundwater: (1) As affected aquifers where geogenic As-bearing mineral dissolute into aquifer water; (2) geothermal water which contain high amount of As that seeps into aquifers and (3) mining-affected water which seep through and contaminate groundwater (Kossoff and Hudson-Edwards 2012; Morales-Simfor et al. 2020). The As concentration in groundwater vary globally due to various sources of arsenic. Higher As concentration (0–48 mg/l) has been recorded from Western USA because of prevailing geochemical environments (Welch et al. 1988), followed by India (0–23.08 mg/l) due to As rich sediment and pesticide production (Mandal et al. 1996; Ghosh et al. 2015a). Notably the Bengal Delta Plains (BDP) spanning across Eastern India and Bangladesh have arsenic-contaminated aquifers mainly due to geogenic activity (Smedley and Kinniburgh 2002) and also represent one of the worst affected regions globally (Mukherjee et al. 2009; Ghosh et al. 2014; Shrivastava et al. 2015; Ghosh et al. 2018). Moreover, 2% of the world’s human population residing in the BDP region consume As-contaminated groundwater almost on a daily basis and this has become a serious public health issue over the last few decades (Ghosh et al. 2015a, b; McArthur 2019; Chikkanna et al. 2019).

River water

As contamination in river water are generally inadequate and reported concentrations are known to vary between 0.13 and 2.1 μg/l in many regions (Kossoff and Hudson-Edwards 2012). However, the range of As is found to be higher in rivers with inputs from volcanic eruptions, weathering and leachate of bedrocks, and other contaminants arising from anthropogenic activities. For example, European rivers such as Tinto (Portugal) and Rios Odiel (Spain) draining through the Iberian pyrite belt contain higher As loads (441 and 1975 μg/l, respectively) due to weathering and dissolution of As-bearing sphalerite, chalcopyrite, tetrahedrite and arsenopyrite (Kuehnelt 2006; Sarmiento et al. 2009). Similarly, in North America, the Gibbon River which drains through the Norris Geyser Basin of Yellowstone National Park, USA contain up to 160 μg/l of As (McCleskey et al. 2010) and stream/river water and sediment of Alaska showed As concentration ranging from 5 to 4000 mg/kg which is usually dominated by metamorphic rocks with mineralized regions (Wilson and Hawkins 1978). However, studies on elevated As level in many global rivers including from India are limited to a large extent. In recent years, the Central Water Commission under directives from the Government of India, have started to monitor As in Indian rivers. Reports suggest that As ranges from 0.01 to 9.47 µg/l, which falls within the permissible limit set WHO. Studies undertaken in the Ganga River Basin system have shown that elevated As level pose serious threat to public health (review by Chakraborti et al. 2018). Studies have also shown that riverbed–aquifer interface constitutes a hotspot for elevated As concentration and sustained release of the same is facilitated by the river muds rich in labile forms of organic matter as well as reactive iron oxides (Wallis et al. 2020).

Marine water

The concentration of As in open ocean is generally low (ranges from 0.003 to 1.8 μg/l) (Maher 1985; Cullen and Reimer 1989; Santosa et al. 1994) compared to coastal water (1 to 4.3 μg/l) (Santosa et al. 1996) or other coastal ecosystems (0.14 to 147 μg/l) including estuaries, lagoons and backwaters (Peterson and Carpenter 1983; Martin et al. 1993; Abdullah et al. 1995; Smedley and Kinniburgh 2002). The As concentration in the Indian Ocean has been reported to be even lower (0.03 to 0.766; Morrison et al. 1997) compared to Pacific (1 to 1.8; Santosa et al. 1996), Atlantic (1 to 1.58; Santosa et al. 1994) and Antarctic Oceans (0.003 to 1.078; Middelburg et al. 1988). The lower concentration of As in the Indian Ocean region could be due to huge fresh water discharged from major rivers and high tidal influx from sea that provides large mixing zone in the Northern part of the Indian Ocean. Cullen and Reimer (1989) suggested that due to this saltwater–freshwater interface, co-precipitation zone of iron (Fe) and As occur which results in floccules formation made up of poorly crystalline Fe oxides as well as oxyhydroxide and precipitates (Anninou and Cave 2009). It has been also reported that inorganic As is ubiquitous in modern ocean and ranges from 15 to 20 nmol/L in the open ocean (Ellwood and Maher 2002; Cutter and Cutter 2006).

Forms of arsenic in aquatic organisms: metabolism and toxicity

Terrestrial organisms such as plants are well known for absorption of iAs from air, water and also from soil. The amount of As in a plant mainly depends on its exposure to surrounding environment contaminated with As. Other than that, most of the terrestrial organisms absorb As residues through consumption of plants and contaminated soils (Mandal and Suzuki 2002). Even though few studies reported the presence of As in both organic and inorganic forms in aquatic biological communities including bacteria, phytoplankton, small and large fishes and mammals, concentrations and biotransformation mechanisms are not well documented. Similar to terrestrial organisms, aquatic organisms can absorb varying concentrations of As from surrounding ecosystems. Aquatic organisms are exposed to many different forms of inorganic and organic arsenic species (arsenicals) commonly through food, water and other environmental sources. Owing to a large variety of physicochemical properties and bioavailability of each form of As, arsenical metabolism is a complex phenomenon. This is further complexed by the influence of other metals and metalloids on arsenic metabolism within and between the species (Mandal and Suzuki 2002).

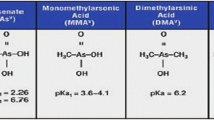

Organic forms of As have been widely observed in aquatic flora and fauna; among them arsenobetaine (AsB) which is the most commonly reported organoarsenical is virtually absent in most of the freshwater invertebrates and vertebrates (Schaeffer et al. 2006). At the same time, an opposite trend has been reported in marine organisms because of major difference in As speciation (Taylor et al. 2017). For example, S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) acts as a donor of methyl group and glutathione acts as a cofactor in the formation of methylated forms of As like monomethylarsonic acid (MMAV) and dimethylarsonic acid (DMAV) (Table 1). Nevertheless, organic As compounds have been also reported from fish lipid extracts (Schäfer et al. 2015; Taylor et al. 2017) and these are mostly arsenolipids that have been observed in higher volume in edible fishes (Arroyo-Abad et al. 2010; Taleshi et al. 2010; Taylor 2017). In a recent study, considerable volume of non-phospholipid forms of As (Fig. 2 modified from Rumpler et al. 2008) has been reported which can be easily transported to upper trophic levels through food web including in humans (Amayo et al. 2011; Sele et al. 2012). Other than that, few of the arsenolipids have been characterized by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) approach and their synthesis pathways have been elucidated by Taleshi et al. (2014). The ingestion pathway, including intake of food and water or through sediment exposure, controls the bioavailability of ingested inorganic arsenic. Besides, nutrients can also play a major role in iAs solubility. Arsenic distribution in aquatic organisms in terms of fate of ingested As in vivo depends on two factors: (1) oxidation and reduction reactions between iAs(V) and iAs(III) and (2) consecutive methylation reactions.

Arsenolipids detected in fish cod oil. The molecular weight of A = 334, B = 362, C = 390, D = 418, E = 388, and F = 436 (adopted from Rumpler et al. 2008)

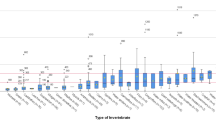

Bioaccumulation refers to the accumulation of any chemical component due to uptake by an organism from surrounding habitat (EPA 2003). It also depends on the type of organismal group (invertebrates, fishes), trophic status within the food chain and duration of exposure and routes of uptake (WHO 2001; Williams et al. 2006). In an aquatic environment, uptake of As by an organism can take place either directly (through ingestion, inhalation and absorption) or indirectly (through food web) (Moss 1998; Mandal and Suzuki 2002; Smedley and Kinniburgh 2002; Smith et al. 2002; Magellan et al. 2014). Smaller marine organisms such as bacteria, microalgae and macroalgae can take up dissolved arsenate from seawater via cellular phosphate transport system [e.g. As(V) is a structural analog of PO43−]. Once inside the organism, the toxic As(V) form is converted into organic forms such as MMA and DMA. These organic As forms get biomagnified once they get accumulated in tissues of higher organisms (e.g. fish) in freshwater and marine environments and this could be possibly due to transformation or bioaccumulation from lower organisms through the food chain (Hellweger and Lall 2004; Rahman and Hasegawa 2012; Rahman et al. 2012; Hasegawa et al. 2019).

Arsenic bioaccumulation at lower trophic levels

Bacteria

Arsenic is toxic to most of the known bacterial groups, although some bacteria can metabolize as well as tolerate arsenic within its microenvironment. Members representing some of the bacterial phyla can use arsenic as an electron donor for autotrophic growth or as an electron acceptor for heterotrophic and anaerobic respiration (Oremland and Stolz 2003). Strains representing the bacterial genera Agrobacterium and Rhizobium utilize As(III) as a sole source of electrons (Páez-Espino et al. 2009) whereas members of Epsilonproteobacteria (e.g. Sulfurospirillum arsenophilum and S. barnesii) utilize arsenic as a respiratory oxidant by coupling along with oxidation of organic matter. Most aquatic bacterial groups metabolize As either through oxidation [As(III) to As(V)] and reduction [As(V) to As(III)], methylation [formation of monomethyl arsine (MMA) and dimethylarsenic acid (DMA)] and demethylation (Oremland and Stolz 2005). For example, strains of Rhodopseudomonas palustris have been reported to methylate arsenic forming mono-, di-, and/or tri-methyl derivatives such as trimethylarsine (Qin et al. 2006). Arsenic resistance in bacterial cell is mainly due to the presence of phosphate-specific transport systems or efficient efflux systems. Phosphate-specific transport system prevents the uptake of arsenic, whereas the plasmid or chromosomally encoded ars operon works to remove arsenic from cells. Of the three arsenate reductases reported in bacteria, ArsC has been widely studied in order to understand detoxification and resistance mechanism. It is a small molecular mass protein of 13–16 kDa which is located in the cytoplasm and plays a role by reducing As(V) to As(III). There are reports that in the bacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris the expression of ars2 or ars3 operons showed an increase with increasing environmental As(III) concentrations (up to 1.0 mM) (Zhao et al. 2020). Macur et al. (2001) reported that Caulobacter-like, Sphingomonas-like and Rhizobium-like genera have metabolic ability to reduce arsenate rapidly. On the other hand, strains belonging to Proteus, Escherichia, Flavobacterium, Corynebacterium and Pseudomonas have been reported to transform As(V) into As(III) and other volatile methylarsines (Shariatpanahi et al. 1981). Thus the presence of highly efficient ars export system leads to low As levels in bacterial cells (review by Shi et al. 2020). There are also reports of parallel genetic pathways for organoarsenical detoxification by bacteria (review by Yang and Rosen 2016). Ghosh and Bhadury (2018) has shown that the stress from As can induce alteration of membrane phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) in arsenite oxidizing bacterial members including Hydrogenophaga bisanensis strain BDP20 and Acidovorax facilis strain BDP24.

Algae

Algae are an important source of organoarsenic compounds in the marine environment. Organic forms of As are synthesized by algae and transferred through the food chain (Wrench et al. 1979). Micro- and macro-algae which form the basis of lower trophic levels may accumulate more As compared to members representing higher trophic levels (Garcı´a-Salgado et al. 2012).

In laboratory experiments it has been shown that euryhaline algae have ability to synthesize fat and water-soluble arseno-organic compounds from iAs (Eisler 1988). Larsen et al. (1993) found that dissolved arsenate from seawater can be accumulated by marine micro- and macroalgae, and incorporated as arsenosugars (Fig. 1) after conversion into arsenobetaine (AsB) and arsenocholine (AsC). Other than MMA and DMA, several other As containing ribosides are also synthesized by marine algae (Francesconi et al. 1992), in addition to enzymatic methylation in the form of methylcobalamin and S-adenosylmethionine (Ridley et al. 1977). There are reports of the potential of algae to take up As(V) by more than one mechanism (Andreae et al. 1979). Several studies have also reported detoxification of As by algae and it is achieved by excreting out methylarsonic acid and DMA from inside the cell and DMA can also be reduced to dimethylarsinyl adenosine form in a reaction with adenosylmethionine. Dimethylarsinoriboses can be formed by glycosidation of this intermediate dimethylarsinyl adenosine which may reduce to trimethylarsonio ribosides. Other complex organoarsenical derivatives like arsenotaurine are also formed within marine algae by similar mechanism and intermediates (Ridley et al. 1977).

Microalgae such as Chlorella sp. and Monoraphidium arcuatum can uptake As(V) and reduce to As(III), while M. arcuatum excretes As(III) out of the cell (Levy et al. 2005). However it had been hypothesized that methylation of As(III) is not the sole detoxification method adopted by freshwater algae. Algal cells can also pump out As(III) from inside which can get oxidized to As(V) (Levy et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2013; Magellan et al. 2014). Other than that, algal cells can oxidize to form As(V). For example, macroalgae such as Fucus spiralis and Ascophyllum nodosum have been shown to accumulate four times more As(V) than As(III) from equivalent concentrations in seawater (Klumpp 1980a). Lai et al. (1998) reported that local climate conditions including seasonality can contribute to varying concentration of arsenosugars accumulation rate in the marine brown alga, Fucus sp. Similarly Francesconi and Edmonds (1993) reported that generally brown algae showed higher levels of total As (up to 230 µg/g dry weight) than red algae (up to 39 µg/g dry weight) and green algae (up to 23.3 µg/g dry weight) (Additional file 1: Table S1). In general it is known that detoxification of As by microalgae can be achieved through adsorption on cell surface (Wang et al. 2013; Dutta and Bhadury 2020; Zhang et al. 2020a, b), intracellular metabolism including As(III) oxidation and reduction of As(V), complexation with thiol compounds and sequestration into vacuoles (Olguı´n and Sa´nchez-Galva´n 2012), methylation and transformation into forms such as arsenosugars and arsenolipids and also by excretion (Levy et al. 2005; Jiang et al. 2011).

Zooplankton

Apart from micro- and macro-algae, drifting organisms such as phytoplankton (horizontal drifter) and zooplankton (vertical drifter) can also accumulate As. Aquatic primary production undertaken mainly by phytoplankton, which can uptake As(V) from the surrounding water and reduce it to As(III) (Sanders et al.1989) and can readily incorporate large quantities of As within their cellular components (Sanders and Cibilt 1985; Blanch and Wangberg 1988). Similarly, Froelich et al. (1985) reported that phytoplankton can also uptake and biomethylate As(III) followed by excreting outside the cell into the environment in forms such as MMA and DMA. These methylated arsenicals and organoarsenic compounds can be transferred to higher trophic levels through accumulation processes (Sanders 1985; Irgolic et al. 1977). A study undertaken by Šlejkovec et al. (2014) has shown that phytoplankton can also accumulate large quantities of iAs and/or can convert into other organic forms like arsenobetaine.

Similarly, traces of AsB have been reported in herbivorous zooplankton while other major As forms have been reported in carnivorous zooplankton (Šlejkovec et al. 2014) and these can ultimately get biomagnified through the marine food chain. Chen and Folt (2000) examined the accumulation and fate of As in different sized zooplankton and reported As bioaccumulation factor (BAF) in small zooplankton to be significantly higher (0.026 to 1.98 mg/kg) compared to larger zooplankton (0.022–0.598 mg/kg). Similarly, they reported a temporal increase in As concentration in zooplankton indicating potentially greater effect through food and their uptake (Chen and Folt 2000). In a very recent study, Hasegawa et al. (2019) showed that some cultured strains of freshwater phytoplankton can rapidly release inorganic and methyl forms of arsenic out of their cells during logarithmic growth phase while organic forms of As remain inside the cells. These findings have huge implications in terms of long-term bioaccumulation of forms of arsenic within zooplankton as part of freshwater trophic levels and beyond.

Arsenic bioaccumulation at higher trophic levels

Like lower trophic level organisms (e.g. microbes, algae, and phyto-zooplankton), higher trophic level organisms (e.g. fishes, crabs, prawns, and shrimps) play a vital role in As speciation within aquatic environments. Varying concentration of total As (Astot) has been reported in various group of Pisces, while iAs levels were found to be uniformly low in most cases (Rahman and Hasegawa 2012). Accumulation of Astot was mainly determined by various primary factors: (1) foraging habits, (2) metabolism and individual variation of As owing to their age, (3) regional differences (farmed vs. wild caught), (4) differences in preparation and sample handling methods, and (5) differences in analytical methods in aquatic foods (Schoof and Yager 2007). Many studies revealed variations of Astot in both marine and freshwater fishes which are important components of the aquatic food chain and directly consumed by higher tropic levels including humans (Schoof and Yager 2007; Rahman and Hasegawa 2012). Bioaccumulation of As in Pisces mainly depends on their habitat and feeding behaviour which may lead to resulting presence of inorganic, methylated and other organoarsenic compounds in their body (Rahman and Hasegawa 2012).

Bioaccumulation and biomagnification of As in Fin fishes

Arsenic can be oxidized or reduced or methylated and subsequently metabolized in all living tissues leading to recurrent bioaccumulation and biomagnification. However, biomagnification is seldom observed (Henry 2003). The Astot concentrations are lower in freshwater fishes and typically have higher iAs:Astot ratios as compared to anadromous, estuarine and marine fishes (EPRI 2003). Trimethyl arsenic have been detected at higher levels than that of dimethyl arsenic compounds in several freshwater fish species such as Plecoglossus altivelis, Oncorhynchus masou, Rhinogobius sp., Sicyopterus japonicus, Phoxinus steindachneri and Abramis brama danubii. These species are representatives of various global geographical locations (Kaise et al. 1997; Šlejkovec et al. 2004).

Many studies observed fish gills, skin and digestive tract as potential sites of absorption of water-soluble forms of As. Although skin may act as an important As absorbing site in small fishes due to their high surface area-to-volume ratio (Rahman and Hasegawa 2012; Magellan et al. 2014), As bioaccumulation and chemical speciation varies greatly in body tissues representing different species (Kar et al. 2011). The organoarsenical form (accumulation of AsB) has been widely reported in freshwater fishes (Jabeen and Javed 2011) and accumulation can vary in different organs (e.g. gills, liver, kidney, intestine, reproductive organs, skin, muscle, fins, scales, bones and adipose tissue) of different species (0.33 ± 0.01 to 1.42 ± 0.04 μg/g; Jabeen and Javed 2011). A diverse group of freshwater fish species such as salmonids (Salmo marmoratus, Salmo trutta fario and Oncorhynchus mykiss), common nase (Chondrostoma nasus), common barbel (Barbus barbus), Danube roach (Rutilus pigus), burbot (Lota lota) and Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) had been seen to accumulate higher As concentrations in muscle tissues compared to other organs (Šlejkovec et al. 2004).

Based on trophic status, bottom feeder fishes can be exposed to greater quantities of As in tissues due to their proximity to contaminated sediments whereas predatory fishes can bioaccumulate As either from surrounding water or from feeding on other fishes. It has been found that juvenile fish have higher concentration of As accumulation compared to adult forms (Schmitt and Brumbaugh 1990). A preliminary study conducted on bluegill fishes in 1960s showed the presence of arsenic residues within the entire body of 16-week-old immature fishes whereas, in mature fishes, arsenic residues were recovered only from their muscle tissues (Gilderhus 1966). Another such study conducted in late 1990s on mullet fishes showed similar concentrations of As in liver and muscle tissue of both juvenile and mature stages (Suner et al. 1999). To measure the difference in As bioaccumulation in different foraging fishes such as Alosa pseudoharengus (alewife), Pomoxis nigromaculatus (black crappie), Lepomis macrochirus (bluegill sunfish), Kryptolebias marmoratus (mangrove killifish) and Perca flavescens (Yellow perch) caught from Upper Mystic Lake, Massachusetts it was found that As burdens of all fishes were 30 to 100 times lower than its burdens in zooplankton. This further reinstates the position within the food chain to be a crucial factor regulating As bioaccumulation and biomagnification (Chen and Folt 2000; Jayaprakash et al., 2015). A recent study has also shown that bioaccumulation of Astot in fishes were significantly correlated with Astot level of pond water (n = 10; R2 = 0.80; p < 0.05; Kar et al. 2011). Thus bioaccumulation of As is a well debated issue in freshwater fishes and alike mercury (Hg) it can get bioaccumulated, transported and biomagnified across higher trophic levels.

The magnitude of accumulation of any element depends widely on its physicochemical properties, fluxes/abundance and hydrophobicity. Inherent different of biological systems could result in high chemical concentrations of As in fin and shellfishes (several orders higher) than in the surrounding aquatic system. Thus, marine fishes which have limited ability to methylate arsenic, accumulate less As(V) from the surrounding in comparison to the fresh water fishes from lower trophic levels (Guven et al. 1999; Neff 2002).

Most of the marine fishes are planktivores and feeds directly phyto/zooplankton as a major food and thus can accumulate various forms of As through plankton (Peshut et al. 2008). On the contrary digestive tissues of estuarine mullets and luderick have shown to accumulate iAs in their tissues (Peshut et al. 2008). Other than iAs, marine fishes also accumulate organic As mainly in the form of arsenobetaine (AsB) which is a major water-soluble compound. It constitutes more than 95% of overall As compounds found in marine fishes (Kirby and Maher 2002). The biomagnification of arsenobetaine has been detected at different trophic positions of marine fishes such as planktivores, herbivores, detritivores and carnivores. However, studies have shown pelagic carnivores to accumulate higher amount of AsB owing to their larger sizes (Kirby and Maher 2002). However, other organic arsenicals such as arsenocholine, tetramethylarsonium ion and arsenosugars have been also found in very low concentrations in marine fishes (Molin et al. 2012; Rahman et al. 2012). Moreover, varying concentrations of Astot have been detected in different tissues of marine fishes irrespective of their trophic position (Langston 1984).

Bioaccumulation and biomagnification of As in shellfish

The amount of As accumulation and biomagnification in shellfishes can also vary based on their feeding preferences as well as on habitats. Arsenic speciation and their amounts fluctuate among marine shellfishes and also with respect to prevailing environmental factors such as temperature, salinity, pH and Eh. Shellfishes accumulate both organic and inorganic forms of As (Taylor et al. 2017), while ca. 90% are organic forms and found in edible portions. Similar to other aquatic finfishes, shellfishes also convert iAs to organic As like arsenobetaine (AsB) and arsenocholine (AsC) and dimethylarsinic acid (DMA), and bioaccumulate in their body parts (Lawrence et al. 1986). Among the shellfishes, crustaceans accumulate higher Astot (170 mg/kg) (Calabrese et al. 1985) compared to others (Penrose et al. 1977). For example, common littoral crab (Carcinus maenas) accumulates both organic and iAs through ingestion; however, they cannot inter-convert these forms in their tissues and rapidly excrete out the inorganic forms compared to organic forms (Andersen and Depledge 1993). Thus, shellfishes have limited ability to accumulate As and there is strong support towards the fact that these levels have increased in the current era (Rodney et al. 2007).

Similarly in marine bivalves, AsB is the prevalent form absorbed in their body muscles; it can come directly via ingestion of phyto-zooplankton, detritus and sediment particles while carbonate shells accumulate from surrounding water column (Shibata and Morita 1992). On the other hand, freshwater clams are known to accumulate higher tetramethylarsonium ion (Shiomi et al. 1987). Lai et al. (1998) reported higher levels of As in the form of arsenosugars in scallops particularly muscles and gonads whereas Rodney et al. (2007) studied As accumulation in an estuarine oyster species (Crassostrea virginica) and showed increasing concentration in muscle tissues with bio-concentration factor (BCF). Nonetheless, depth-wise distribution of oyster shell exhibit marked variation in organic As bioaccumulation (top: 0.213 ± 0.037 µg/g, bottom: 0.092 ± 0.018 µg/g) whereas iAs accumulation is not distinctly detected (Sanders et al. 1989). The higher concentration of As in oyster shell can be found based on studied geographical regions such as the West coast of Florida, USA which receives more phosphates from mineral deposits. Other studies involving deposit-feeding bivalve Scrobicularia plana and filter-feeding bivalves Cerastoderma edule and Mytilus edulis are shown to accumulate As from sediment particles through ingestion whereas grazing gastropod such as Littorina sp. which fed on various macroalgae can also accumulate As (Klumpp 1980b). Similarly, As in soft tissues of the bivalve Modiolus capax (commonly known as fathorse mussel) has been detected and ranges from 6.62 to 44.7 µg/g of dry weight (Gutierrez-Galindo et al. 1994). In bivalves such as the blue mussels (Mytilus edulis), high concentrations of iAs ranging between 0.001 and 4.5 mg As/kg has been reported (Sloth and Julshamn 2008). However, As speciation and accumulation and magnification rates are not very well documented in most of the edible shellfishes including shrimps, prawns and molluscs.

Effect of arsenic on aquatic biota

Aquatic environments are exposed to arsenic through atmospheric deposition of combustion products and run-off from fly-ash storage areas. Arsenical compounds have been detected in aquatic biota and can go up to 48 µg/l in water, 120 mg/kg in diets and 5 mg/kg (fresh weight) in tissues (Eisler 1988). Effects of arsenicals in aquatic organisms including toxicity are significantly modified by number of biotic and abiotic factors.

Freshwater biota

Only few studies have been undertaken to investigate effect of As on freshwater algae. Thegrowth rate experiments conducted on three different freshwater algal species namely Ankistrodesmus falcatus, Scenedesmus obliquus and Selenastrum capricornutum indicated a decrease in growth at 0.075 mg/l of As(V) concentration (EPA 1985). Whereas, freshwater invertebrates species like Bosmina longirostris, Daphnia magna, Daphnia pulex and Simocephalus serrulatus when treated with As(III) concentration of 1.5 mg/l for 96 h resulted in 50% immobilization and followed by three weeks exhibited impaired reproduction (Lima et al. 1984; Passino and Novak 1984). Spehar et al. (1980) conducted 28 days (LC-10) experiment using As(III) and As(V) on Helisoma campanulata and showed that As(III) had more lethal effect than As(V). In another study on Pteronarcys californica and Pteronarcys dorsata showed a LC-50 of 96 h (3.8 mg/kg) and 28 h (0.96 mg/kg) of As concentration ultimately resulting in mortality (Johnson and Finley 1980). But, it should be noted that LC-50 values are markedly affected by surrounding water temperature, pH, Eh, organic load and phosphate concentrations, suspended solids and presence of other substances and toxicants (Kumari et al., 2017). Besides, As speciation and duration of exposure can also affect these values (Eisler 1988).

Among freshwater vertebrates, marbled salamander (Ambystoma opacum) and eastern narrow-mouthed toad (Gastrophryne carolinensis) showed death or malformations in developing embryos when exposed to As at a concentration of 0.04 mg/l. The juvenile of bluegill fish (Lepomis macrochirus) showed reduced survival rate and histopathological changes when treated with 0.69 mg/kg of As for 16 weeks (EPA 1985) while goldfish (Carassius auratus) shows 15% behaviour impairment in 24 h and nearly two fold in 48 h when exposed to As. In another study, the flagfish (Jordanella floridae) showed mortality when exposed to As with and without food resulting in 96 h LC50 estimate of 14,400 µg/l (Lima et al. 1984). Another experiment carried out using 96 h exposure to As (based on LD50 values) in spottail shiner (Notropis hudsonius), chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), common minnow (Phoxinus phoxinus) and fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas) showed fins were more affected than edible muscle tissues (Lima et al. 1984; EPA 1985). Similarly, the embryo and adults of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) showed a depression in growth with avoidance of food and impaired feeding efficiency at different concentrations of As (Johnson and Finley 1980; Cockell and Hilton 1985).

Marine biota

Marine bacteria and algae are thought to preferentially utilize As(III) form of arsenic in their environment (Johnson 1972; Johnson and Burke 1978). It is also believed that As(V) form has more profound effect on growth and morphology of marine algae compared to As(III). An experiment involving incubation of marine algae in media containing various concentrations of As(V) and As(III) have shown arsenic incorporation and release from algal cells thereby indicating that the differences between uptake and release rate have hinted towards chemical changes of As(V) upon incorporation inside algal cells (Bottino et al. 1978). There are numerous reports of changes at the morphological and physiological levels in marine algae due to exposure from arsenic. For example, reduced sexual reproduction and sporulation have been reported in red algae (Champia parvula and Plumaria elegans) following exposure up to 0.6 mg/l of As (Thursby and Steele 1984; Sanders 1986). Similarly, inhibition to growth, reduction of Chlorophyll-a, and overall biomass reduction has been observed in Skeletonema costatum and Thalassiosira aestivalis when exposed to arsenic (EPA 1985).

Among marine invertebrates, amphipods (Gammarus pseudolimnaeus) showed 50% immobilization in 96 h at 0.87 mg/l of As in water (Lima et al. 1984). Ricevuto et al. (2016) conducted an in-situ experiment (30 days) on polychaete (Sabella spallanzanii) near the CO2 vent and reported elevated concentration of arsenic in their gills, particularly dimethylarsinic acid (DMA), stored as an anti-predatory compound. This study also concluded low pH and high pCO2 may have detrimental effects on arsenic metabolism and oxidative status of this polychaete species provide an insight to understanding of species-specific vulnerability to ocean acidification. Similarly, very low As concentration were found in the copepods (e.g. Acartia clausi) and Dungeness crabs (Cancer magister) when exposed to As treated water (LD50 at 96 h) (EPA 1985) while reduced survival rate has been observed in juvenile and adult stages of calanoid copepods (Eurytemora affinis) when exposed to arsenic (arsenate form-100 µg/l) (Sanders 1986). The gastropod shells (Nassarius obsoletus) showed decreased consumption of food whereas bivalve shells (Mytilus edulis) showed mortality within 3 to 16 days of As treated water (NAS 1977). In higher tropic level, fishes like thicklip grey mullet (Chelon labrosus) and common dab (Limanda limanda) reported discoloration of skin and respiratory problems, respectively, in environments with high As concentration (Taylor et al. 1985; Scott and Sloman 2004).

Biomagnification in aquatic ecosystems and trophic levels

The effects of As on aquatic ecosystems and beyond including on human health are influenced by the nature of persistence as well as ability to increase toxicity potential from lower to higher trophic levels (e.g. microbes to fish to humans). This process is known as biomagnification. As discussed, forms of arsenic can disrupt the growth of various groups of organisms in aquatic ecosystems including plankton, molluscs and crustaceans as well as can adversely affect photosynthetic process with cascading impacts on productivity of these ecosystems (Newman 2015; review by Córdoba-Tovar et al. 2022). The adverse effects of As biomagnification and consequences such as decreased reproductive capacity, changes in embryo viability, teratogenesis as well as changes in enzymatic processes have been documented in many higher trophic levels inhabiting aquatic ecosystems (Zheng et al. 2019). Many studies have highlighted that biomagnification in aquatic ecosystems represents a combination of several factors including environmental, ecological and biological factors (Zhang et al. 2012; Huang 2016). It seems that bioaccumulation and biomagnification of As in aquatic ecosystems are not very consistent when demonstrating increase in concentrations of forms of arsenic such as from algae to zooplankton or from zooplankton to fish (Majer et al. 2014; Kato et al. 2020). Studies have shown that the concentration level of forms of As in freshwater systems is dependent on the rate of biodilution compared to marine systems where it is more linked to enrichment of organic form (arsenobetaine). As a result, there is degradation of food with high arseno-sugar contents (Caumette et al. 2012; Huang 2016). There are reports that have shown biomagnification of forms of As can be favoured by a combination of factors including benthic habitat and environmental factors in marine ecosystems (Du et al. 2021). In general, due to the effect of biodilution of As along food webs, negative effects may be prominent in organismal groups representing low trophic levels in aquatic ecosystems (Trevizani et al. 2018). Studies have also shown a temporal trend of biomagnification in higher trophic levels across aquatic ecosystems with higher concentrations reported in benthic fish during winter while pelagic fish had lower concentration in summer (Du et al. 2021). There are reports of a rise in lipid-soluble As concentrations in pelagic organismal groups from marine environment with concentrations higher in crustaceans compared to bottom dwelling fish (Hayase et al. 2010; Córdoba-Tovar et al. 2022). Some studies also indicate that biomagnification of As in higher trophic levels can be linked to age and accumulation tends to be species-specific (Agusa et al. 2008). It has been also observed that biomagnification of As can vary with respect to type and complexity of food web (Dovick et al. 2015; Huang 2016). Based on a number of studies it has been also proposed that retention capacity, assimilation, metabolization and exposure time can be crucial factors that can strongly influence biomagnification of forms of As across trophic levels and linked feeding habitats (Maher et al. 2011). While numerous studies have shown some indication of the steps of biomagnification of As in aquatic ecosystems; however, answers pertaining to trophodynamics and link with biomagnification are yet to be fully resolved.

Arsenic metabolism and toxicity in humans

Food is considered to be the primary source of As intake in human besides exposure from occupation or from drinking water. In humans, As(V) is rapidly reduced to As(III) and partly methylated in vivo. DMA is an important metabolite reported in most of the animals whereas 20% inorganic arsenic, 20% MMA and 60% DMA have been found in human urine under normal conditions (Mandal and Suzuki 2002). Under in vivo condition this iAs gets methylated to MMA and DMA and absorbed MMA is further methylated to DMA and ultimately excreted mainly in unchanged forms (Buchet et al. 1981, 1996a) while AsB is absorbed and excreted as unchanged form (Brown et al. 1990). Mandal et al. (2001) found that MMAV can be reduced to their trivalent analogues, monomethylarsonous acid (MMAIII) and DMAV as dimethylarsinous acid (DMAIII) based on the detection in human urine.

An experimental observation showed 33% of As excreted in urine within 48 h and remaining 45% within 96 h when using 500 g of As(III) and similarly radioactively labelled (74As) showed 38% excretion in 48 h and 58% in 120 h (Tam et al. 1979; Buchet et al. 1981). However, As excretion can also happen through other routes (e.g. sweating) and it can also accumulate in keratin-containing tissues (e.g. skin, hair and nails) and mother’s milk whilst these latter routes of excretion are not that frequent (Grandjean et al. 1995; WHO 2001). Although these keratin-containing tissues are used as indicators for identifying As exposure to humans but blood is also used to detect recent As poisoning or in terms of chronic stable exposure (Ellenhorn 1997). Other than that, consumption of aquatic products particularly seafood (e.g. shrimp, marine fishes, other crustaceans, bivalves and seaweeds) and other products (e.g. freshwater fishes, prawns and clams) by human is increasing day-by-day which can ultimately lead to As toxicity provided that the source of food have significantly higher amount of As metabolites (e.g. MMA, DMA and arsenosugars; Kumari et al., 2017). Therefore, As metabolites (iAs + MMA + DMA) are used as an index to elucidate Astot exposure in human urine to correctly estimate iAs exposure in human population (WHO 2001). However, the As metabolites index is not well recognized globally. In particular, across parts of South and South-east Asia there is a need to integrate and rapidly use As metabolites index so as to understand the scale and magnitude of As bioaccumulation in human populations. This is particularly relevant given changing groundwater scenarios in many parts of Asia induced by anthropogenic climate change (Shah 2019) which can increase exposure to As toxicity across local, regional and transboundary scales (e.g. India and Bangladesh). There is an urgent need to develop cost-effective methods of estimation iAs exposure in order to effectively reach out to many of the developing and least-developing countries facing As exposure issues across pan continents. The Figure 3 provides a representation of translocation of arsenic from lower to higher trophic levels.

Conclusions and way forward

Arsenic poses serious health risk as it enters the human body through drinking water and contaminated food sources such as rice grains. However, the entry of arsenic in human body through consumption of freshwater and marine fish or shellfish has not been thoroughly investigated across large geographical scales, in particular from many countries which are reeling from geogenic arsenic issues. A large number of investigations have established the presence of high concentration of As in aquatic environments including aquatic biota through routes of bioaccumulation. Therefore, As bioaccumulation in inorganic forms or organic forms such as momomethylarsenic acid (MMA) and dimethylarsenic acid (DMA) and arsenobetaine (AsB) can result in biomagnification at higher trophic level (including human) and ultimately lead to serious public health issues. However, only a limited number of investigations have looked into As bioaccumulation and their contamination on fresh and marine water including associated biodiversity which warrants further scientific investigations. This review provides a much-needed understanding of As bioaccumulation and biomagnification through various trophic levels including fin fishes and shellfishes which are consumed by humans and are known to be potential health hazard.

In the era of ‘omics’ there is a need to integrate genomics, proteomics and metabolomics approaches in order to better understand the effect of bioaccumulation and biomagnification particularly in aquatic biota by investigating influx and efflux of inorganic arsenic species. For example, it is now becoming increasingly clearer that As(III) can enter living system through the involvement of other transport systems such as aquaporins (Thomas 2007). It is essential to characterize the genes that code for aquaporins in different organismal groups including in fishes. Other pathways such as the hexose permease transporter (HXT) can modulate uptake of As (III) with a higher efficiency compared to aquaporins. However, the distribution patterns of HXT needs to be more thoroughly investigated using ‘omics’ based approach in different organisms which have shown tendency to bioaccumulate As. Similarly, mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are important regulatory proteins through which extracellular signals are transduced into intracellular events. It seems that arsenic can affect the MAPK pathway and therefore this pathway has to be thoroughly investigated in higher trophic levels.

Given the ability of microbiome in human gut to biochemically transform arsenicals (Coryell et al. 2019), there requires an international effort to elucidate the responses of human gut microbiome to As toxicity spanning geographical scales and representing diversity of populations. Such effort can be crucial towards linking As induced toxicity and manifestations in terms of other pathological ailments including cancer. The availability of third and fourth generation sequencing technologies (e.g. Illumina and Oxford Nanopore) (review by Bhadury and Ghosh 2022) along with robust computational biology tools provide the right time and opportunity to undertake human gut microbiome studies involving As affected populations of South Asia and beyond. The possibility of initiating long-term monitoring programmes of deep and shallow aquifers in countries such as India and Bangladesh through pan collaborative network can be immensely helpful towards understanding As bioaccumulation in the era of ‘Anthropocene’. Overall, in future, understanding the consequences of bioaccumulation particularly in aquatic biota using ‘omics’ tools can ultimately pave the way for As metalloid-free environment and food resources.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Abdullah M, Shiyu Z, Mosgren K (1995) Arsenic and selenium species in the oxic and anoxic waters of the Oslofjord, Norway. Mar Pollut Bull 31:116–126

Agusa T, Takagi K, Kubota R, Anan Y, Iwata H, Tanabe S (2008) Specific accumulation of arsenic compounds in green turtles (Chelonia mydas) and hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) from Ishigaki Island, Japan. Environ Pollut 153:127–136

Amayo KO, Petursdottir A, Newcombe C, Gunnlaugsdottir H, Raab A, Krupp EM, Feldmann J (2011) Identification and quantification of arsenolipids using reversed-phase HPLC coupled simultaneously to high-resolution ICPMS and high-resolution electrospray MS without species-specific standards. J Anal Chem 83:3589–3595

Andersen JL, Depledge MH (1993) Arsenic accumulation in the shore crab Carcinus maenas: the influence of nutritional state, sex and exposure concentration. Mar Biol 118:285–292

Andreae MO (1979) Arsenic speciation in seawater and interstitial waters: the influence of biological–chemical interactions on the chemistry of a trace element. Limnol Oceanogr 24:440–452

Anninou P, Cave RR (2009) How conservative is arsenic in coastal marine environments? A study in Irish coastal waters. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 82:515–524

Argos M, Kalra T, Rathouz PJ, Chen Y, Pierce B, Parvez F, Islam T, Ahmed A, Rakibuz-Zaman M, Hasan R, Sarwar G, Slavkovich V, van Geen A, Graziano J, Ahsan H (2010) Arsenic exposure from drinking water, and all-cause and chronic-disease mortalities in Bangladesh (HEALS): a prospective cohort study. Lancet 376:252–258

Arroyo-Abad U, Mattusch J, Mothes S, Moeder M, Wennrich R, Elizalde Gonzalez MP, Matysik FM (2010) Detection of arsenic-containing hydrocarbons in canned cod liver tissue. Talanta 82:38–43

Bissen M, Frimmel FH (2003) Arsenic-a review. Part I: occurrence, toxicity, speciation, and mobility. Acta Hydroch Hydrob 31:9–18

Bhadury P, Ghosh A (2022) The use of molecular tools to characterize functional microbial communities in contaminated areas. In: Das S, Dash HR (Eds) Microbial Biodegradation and Bioremediation (2nd Edition). Elsevier. pp 55–68

Blanch H, Wangberg SA (1988) Validity of an ecotoxicological test system: short-term and long-term effects of arsenate on marine periphyton communities in laboratory systems. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 45:1807–1815

Borba RP, Figueriredo BR, Matschullat J (2003) Geochemical distribution of arsenic in waters, sediments and weathered gold mineralized rocks from Iron Quadrangle, Brazil. Env Geo 4:39–52

Bottino NR, Cox ER, Irgolic KJ, Maeda S, McShane WJ, Stockton RA, Zingaro RA (1978) Arsenic uptake and metabolism by the alga Tetraselmis chui. Organometals Organometalloids 8:116–129

Boyle RW, Jonasson IR (1973) The geochemistry of arsenic and its use in geochemical prospecting. J Geo Explor 2:251–296

Brown RM, Newton D, Pickford CJ, Sherlock JC (1990) Human metabolism of arsenobetaine ingested with fish. Hum Exp Toxicol 9:41–46

Buchet JP, Lauwerys R, Roels H (1981) Comparison of the urinary excretion of arsenic metabolites after a single oral dose of sodium arsenite, monomethylarsonate, or dimethylarsinate in man. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 48:71–79

Buchet JP, Staessen J, Roels H, Lauwerys R, Fagard R (1996a) Geographical and temporal differences in the urinary excretion of inorganic arsenic: a Belgian population study. Occup Envir Med 53:320–327

Calabrese EJ, Canada AT, Sacco C (1985) Trace elements and public health. Annu Rev Pub Health 6:131–146

Caumette G, Koch I, Reimer KJ (2012) Arsenobetaine formation in plankton: a review of studies at the base of the aquatic food chain. J Environ Monit 14:2841–2853

Chakraborti D, Basu GK, Biswas BK, Chowdhury UK, Rahman MM, Paul K, Roy Chowdhury T, Chanda CR, Lodh D (2001) Characterization of arsenic bearing sediments in Gangetic delta of West Bengal- India. In: Chappell WR, Abernathy CO, Calderon RL (eds) Arsenic exposure and health effects. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Lausanne, New York, Oxford, Tokyo, pp 27–52

Chakraborti D, Singh SK, Rahman MM, Dutta RN, Mukherjee SC, Pati S, Kar PB (2018) Groundwater arsenic contamination in the Ganga River Basin: a future health danger. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15:180

Chen CY, Folt CL (2000) Bioaccumulation and diminution of arsenic and lead in a freshwater food web. Environ Sci Technol 34:3878–3884

Chikkanna A, Mehan L, Ghosh KSP, D, (2019) Arsenic exposures, poisoning, and threat to human health: arsenic affecting human health. In: Papadopoulou P, Marouli C, Misseyanni A (eds) Environmental exposures and human health challenges. IGI Global, Hershey, PA, pp 86–105. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-7635-8.ch004

Chilvers DC, Peterson PJ (1987) Global cycling of arsenic. In: Meema KM (ed) Lead, mercury, cadmium and arsenic in the environment (Hutchinson TC. Wiley, Chichester, pp 279–303

Chung J-Y, Yu S-D, Hong Y-S (2014) Environmental source of arsenic exposure. J Prev Med Public Health 47:253–257

Cockell KA, Hilton JW (1985) Preliminary investigations on the comparative chronic toxicity of dietary inorganic and organic arsenicals to rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri R.). Aquatic Toxicol 12:73–82

Colbourn P, Alloway BJ, Thornton I (1975) Arsenic and heavy metals in soils associated with regional geochemical anomalies in South-West England. Sci Total Environ 4:359–363

Córdoba-Tovar L, Marrugo-Negrete J, Barón PR, Díez S (2022) Drivers of biomagnification of Hg, As and Se in aquatic food webs: a review. Environ Res 204:112226

Coryell M, Roggenbeck BA, Walk ST (2019) The Human Gut Microbiome’s Influence on Arsenic Toxicity. Curr Pharmacol Rep 5:491–504

Cullen WR, Reimer KJ (1989) Arsenic speciation in the environment. Chem Rev 89:713–764

Cutter GA, Cutter LS (2006) Biogeochemistry of arsenic and antimony in the North Pacific Ocean. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 7:Q05M08

Dovick M, Kulp T, Arkle R, Pilloid D (2015) Ecological partitioning of arsenic and antimony in a freshwater ecosystem impacted by mine drainage. Environ Chem Chem 13:149–159

Du S, Zhou Y, Zhang L (2021) The potential of arsenic biomagnification in marine ecosystems: a systematic investigation in Daya Bay in China. Sci Total Environ 773:145068

Dutta S, Bhadury P (2020) Effect of arsenic on exopolysaccharides production in a diazotrophic cyanobacterium. J Appl Phycol 32:2915–2926

Eisler R (1988) Arsenic hazards to fish, wildlife, and invertebrates: a synoptic review. Contaminant hazard reviews. Biol Rep 85:1–12

Ellenhorn MJ (1997) Arsenic. In: Ellenhorn’s medical toxicology: diagnosis and treatment of human poisoning, 2nd edn, Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, p 1538.

Ellwood MJ, Maher WA (2002) An automated hydride generation-cryogenic trapping-ICP-MS system for measuring inorganic and methylated Ge, Sb and As species in marine and fresh waters. J Anal at Spectrom 17:197–203

EPA (1985) Ambient water quality criteria for arsenic—1984. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Rep. 440/5-84-033. p 66.

EPA (2003) Technical summary of information available on the bioaccumulation of arsenic in aquatic organisms. U.S. Environ. Protection Agency. EPA-822-R-03-032.

Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) (2003) Critical evaluation of ambient water quality criteria for arsenic. Electric Power Research Institute, Palo Alto, CA, USA. EPRI document 1009211. Prepared by Integral Consulting, Inc, Mercer Island, WA.

Francesconi KA, Edmonds JS (1993) Arsenic in the sea. Oceanog Mar Biol Ann Rev 31:111–151

Francesconi KA, Edmonds JS, Sick RV (1992) Arsenic compounds from the kidney of the giant clam Tridacna maxima. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1:1349–1357

Froelich PN, Kaul LW, Byrd JT, Andreas MO, Roe KK (1985) Arsenic, barium, germanium, tin, dimethylsulfide and nutrient biogeochemistry in Charlotte Harbor, Florida, a phosphorus-enriched estuary. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 20:239–264

García-Salgado S, Quijano MA, Bonilla MM (2012) Arsenic speciation in edible alga samples by microwave-assisted extraction and high performance liquid chromatography coupled to atomic fluorescence spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta 714:38–46

Ghosh D, Bhadury P (2018) Microbial cycling of arsenic in the aquifers of Bengal Delta Plains (BDP). In: Adhya TK, Lal B, Mohapatra B, Paul D, Das S (eds) Advances in soil microbiology: recent trends and future prospects. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6178-3_5

Ghosh D, Bhadury P, Routh J (2014) Diversity of arsenite oxidizing bacterial communities in arsenic-rich deltaic aquifers in West Bengal, India. Front Microbiol 5:1–14

Ghosh D, Routh J, Bhadury P (2015a) Characterization and microbial utilization of dissolved lipid organic fraction in arsenic impacted aquifers (India). J Hydrol 527:221–233

Ghosh D, Routh J, Därio M, Bhadury P (2015b) Elemental and biomarker characteristics in a Pleistocene aquifer vulnerable to arsenic contamination in the Bengal Delta Plain, India. App Geochem 61:87–98

Gilderhus PA (1966) Some effects of sublethal concentrations of sodium arsenite on bluegills and the aquatic environment. Trans Am Fish Soc 95:289–296

Grandjean P, Weihe P, Needham LL, Burse VW, Patterson DG, Sampson EJ, Jorgensen PJ, Vahter M (1995) Relation of a seafood diet to mercury, selenium, arsenic, and polychlorinated biphenyl and other organochlorine concentrations in human milk. Environ Res 71:29–38

Grotti M, Soggia F, Lagomarsino C, Goessler W, Francesconi KA (2008) Arsenobetaine is a significant arsenical constituent of the red Antarctic alga Phyllophora antarctica. Environ Chem 5:171–175

Gutierrez-Galindo EA, Muñoz GF, Villaescusa Celaya JA, Chimal AA (1994) Spatial and temporal variations of arsenic and selenium in a biomonitor (Modiolus capax) from the Gulf of California, Mexico. Mar Pollut Bull 28:330–333

Guven K, Ozbay C, Unlu E, Satar A (1999) Acute lethal toxicity and accumulation of copper in Gammarus pulex (L.) (Amphipoda). Turk J Biol 23:513–521

Han JM, Park HJ, Kim JH, Jeong DH (2019) Toxic effects of arsenic on growth, hematological parameters, and plasma components of starry flounder, Platichthys stellatus, at two water temperature conditions. Fish Aquatic Sci 22:3

Hasegawa H, Papry RI, Ikeda E, Omori Y, Mashio AS, Maki T, Rahman A (2019) Freshwater phytoplankton: biotransformation of inorganic arsenic to methylarsenic and organoarsenic. Sci Rep 9:12074

Hayase D, Agusa T, Toyoshima S, Takahashi S, Horai Hirata S, Itai T, Omori K, Nishida S, Tanabe S (2010) Biomagnification of arsenic species in the deep-sea ecosystem of the Sagami Bay, Japan. Interdiscip Stud Environ Chem 4:199–204

Hellweger FL, Lall U (2004) Modeling the effect of algal dynamics on arsenic speciation in Lake Biwa. Environ Sci Technol 38:6716–6723

Henry TR (2003) Technical summary of information available on the bioaccumulation of arsenic in aquatic organisms. Office of Science and Technology Office of Water, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, p 42.

Huang JH (2016) Arsenic trophodynamics along the food chains/webs of different ecosystems: a review. Chem Ecol 32:803–828

IPCS Environmental Health Criteria (2001) 224: arsenic and arsenic compounds. WHO, Geneva, p 521

Irgolic KJ, Woolson EA, Stockton RA, Newman RD, Bottino NR, Zingaro RA, Kearney PC, Pyles RA, Maeda S, McShane WJ, Cox ER (1977) Characterization of arsenic compounds formed by Daphnia magna and Tetraselmis chui from inorganic arsenate. Environ Health Persp 19:61–66

Jabeen G, Javed M (2011) Evaluation of arsenic toxicity to biota in river Ravi (Pakistan) aquatic ecosystem. Int J Agr Biol Eng 13:929–934

Jankong P, Chalhoub C, Kienzl N, Goessler W, Francesconi KA, Visoottiviseth P (2007) Arsenic accumulation and speciation in freshwater fish living in arsenic-contaminated waters. Environ Chem 4:11–17

Jayaprakash M, Kumar RS, Giridharan L, Sujitha SB, Sarkar SK, Jonathan MP (2015) Bioaccumulation of metals in fish species from water and sediments in macrotidal Ennore creek, Chennai, SE coast of India: a metropolitan city effect. Ecotoxic Environ Saf 120:243–255

Jiang Y, Purchase D, Jones H, Garelick H (2011) Technical note: effects of arsenate (As5+) on growth and production of glutathione (GSH) and phytochelatins (PCS) in Chlorella vulgaris. Int J Phytoremediat 13:834–844

Johnson DL (1972) Bacterial reduction of arsenate in sea water. Nature 240:44–45

Johnson DL, Burke RM (1978) Biological mediation of chemical speciation II. Arsenate reduction during marine phytoplankton blooms. Chemosphere 7:645–648

Johnson WW, Finley MT (1980) Handbook of acute toxicity of chemicals to fish and aquatic invertebrates. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Resource Publications, pp 137–198

Kabata-Pendias A, Pendias H (1984) Trace elements in soils and plants. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, p 315

Kaise T, Ogura M, Nozaki T, Saitoh K, Sakurai T, Matsubara C, Watanabe C, Hanaoka K (1997) Biomethylation of arsenic in an arsenic-rich freshwater environment. Appl Organomet Chem 11:297–304

Kar S, Maity JP, Jean J, Liu C, Liu C, Bundschuh J, Lu H (2011) Health risks of human intake of aquacultural fish: arsenic bioaccumulation and contamination. J Environ Sci Health Part A 46:1266–1273

Kato LS, Ferrari RG, Leite JVM, Conte-Junior CA (2020) Arsenic in shellfish: a systematic review of its dynamics and potential health risks. Mar Pollut Bull 161:111–693

Kirby J, Maher W (2002) Tissue accumulation and distribution of arsenic compounds in three marine fish species: relationship to trophic position. Appl Organomet Chem 16:108–115

Klumpp DW (1980a) Accumulation of arsenic from water and food by Littorina littoralis and Nucella lapillus. Mar Biol 58:265–274

Klumpp DW (1980b) Characteristics of arsenic accumulation by the seaweeds Fucus spiralis and Ascophyllum nodosum. Mar Biol 58:257–264

Kossoff D, Hudson-Edwards KA (2012) Arsenic in the environment. In: Santini JM, Ward SM, Eds. Chapter 1: The metabolism of arsenite arsenic in the environment series, 5, CRC Press, London, pp 1–23.

Kuehnelt D (2006) Arsenic speciation in freshwater organisms from the river Danube in Hungary. Talanta 69:856–865

Kumari B, Kumar V, Sinha AK et al (2017) Toxicology of arsenic in fish and aquatic systems. Environ Chem Lett 15:43–64

Lai VW, Cullen WR, Harrington CF, Reimer KJ (1998) Seasonal changes in arsenic speciation in Fucus species. Appl Organomet Chem 12:243–251

Langston WJ (1984) Availability of arsenic to estuarine and marine organisms: a field and laboratory evaluation. Mar Biol 80:143–154

Larsen EH, Pritzl G, Hansen SH (1993) Arsenic speciation in seafood samples with emphasis on minor constituents: an investigation using high-performance liquid chromatography with detection by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J Anal Atom Spectrom 8:1075–1084

Lawrence JF, Michalik P, Tam G, Conacher HBC (1986) Identification of arsenobetaine and arsenocholine in Canadian fish and shellfish by high-performance liquid chromatography with atomic absorption detection and confirmation by fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem 34:315–319

Levy JL, Stauber JL, Adams MS, Maher WA, Kirby JK, Jolley DF (2005) Toxicity, biotransformation, and mode of action of arsenic in two freshwater microalgae (Chlorella sp. and Monoraphidium arcuatum). Environ Technol Chem 24:2630–2639

Lima AR, Curtis C, Hammermeister DE, Markee TP, Northcott CE, Brooke LT (1984) Acute and chronic toxicities of arsenic (III) to fathead minnows, flagfish, daphnids, and an amphipod. Arch Environ Cont Toxicol 13:595–601

Macur RE, Wheeler JT, McDermott TR, Inskeep WP (2001) Microbial populations associated with the reduction and enhanced mobilization of arsenic in mine tailings. Environ Sci Technol 35:3676–3682

Magellan K, Barral-Fraga L, Rovira M, Srean P, Urrea G, García-Berthou E, Guasch H (2014) Behavioural and physical effects of arsenic exposure in fish are aggravated by aquatic algae. Aquat Toxicol 156:116–124

Maher WA (1985) Distribution of arsenic in marine animal: relationship to diet. Comp Biochem Physiol 82:433–434

Maher WA, Foster SD, Taylor AM, Krikowa F, Duncan EG, Chariton AA (2011) Arsenic distribution and species in two Zostera capricorni seagrass ecosystems, New South Wales, Australia. Environ Chem 8:9–18

Majer AP, Petti Mô TN, Corbisier AP, Ribeiro CYS, Theophilo PA, de Ferreira L, Figueira RCL (2014) Bioaccumulation of potentially toxic trace elements in benthic organisms of Admiralty Bay (King George Island, Antarctica). Mar Pollut Bull 79:321–325

Mandal BK, Suzuki KT (2002) Arsenic round the world: a review. Talanta 58:201–235

Mandal BK, Chowdhury TR, Samanta G, Basu GK, Chowdhury PP, Chanda CR, Lodh D, Karan NK, Dhar RK, Tamil DK, Das D, Saha KC, Chakraborti D (1996) Arsenic in groundwater in seven districts of West Bengal, India. Curr Sci 70:976–986

Mandal BK, Ogra Y, Suzuki KT (2001) Identification of dimethylarsinous and monomethylarsonous acids in human urine of the arsenic-affected areas in West Bengal, India. Chem Res Toxicol 14:371–378

Martin JM, Guan DM, Elbaz-Poulichet F, Thomas AJ, Gordeev VV (1993) Preliminary assessment of the distributions of some trace elements (As, Cd, Cu, Fe, Ni, Pb and Zn) in a pristine aquatic environment: the Lena River estuary (Russia). Mar Chem 43:185–199

McArthur JM (2019) Arsenic in groundwater. In: Sikdar PK (ed) Groundwater development and management. Springer, Cham, pp 279–308

McCleskey RB, Nordstrom DK, Susong DD, Ball JW, Taylor HE (2010) Source and fate of inorganic solutes in the Gibbon River, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, USA. II. Trace element chemistry. J Volcanol Geoth Res 196:139–155

McGeer JC, Brix KV, Skeaff JM, DeForest DK, Brigham SI, Adams WJ, Green A (2003) Inverse relationship between bioconcentration factor and exposure concentration for metals: Implications for hazard assessment of metals in the aquatic environment. Environ Toxicol Chem 22:1017–1037

Meng X, Bang S, Korfiatis GP (2000) Effects of silicate, sulfate, and carbonate on arsenic removal by ferric chloride. Wat Res 34:1255–1261

Middelburg JJ, Hoede D, Van Der Sloot HA, Van Der Weijden CH, Wijkstra J (1988) Arsenic, antimony and vanadium in the North Atlantic Ocean. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 52:2871–2878

Molin M, Ulven SM, Dahl L, Telle-Hansen VH, Holck M, Skjegstad G, Ledsaak O, Sloth JJ, Goessler W, Oshaug A, Alexander J, Fliegel D, Ydersbond TA, Meltzer HM (2012) Humans seem to produce arsenobetaine and dimethylarsinate after a bolus dose of seafood. Environ Res 112:28–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2011.11.007

Morales-Simfor J, Bundschuh I, Herath C, Inguaggiato AT et al (2020) Arsenic in Latin America: a critical overview on the geochemistry of arsenic originating from geothermal features and volcanic emissions for solving its environmental consequences. Sci Total Environ 716:135564

Morrison RJ, Gangaiya P, Naqasima M, Naidu R (1997) Trace metal studies in the Great Astrolabe Lagoon, Fiji, a pristine marine environment. Mar Pollut Bull 34:353–356

Moss B (1998) Ecology of fresh waters, 3rd edn. Blackwell Science, Oxford

Mukherjee A, Fryar AE, Thomas WA (2009) Geological, geomorphic and hydrologic framework and evolution of the Bengal basin, India and Bangladesh. J Asian Earth Sci 34:227–244

NAS (1977) Medical and biological effects of environmental pollutants: arsenic. National Academy of Sciences, Washington, D.C., p 332

Neff JM (2002) Bioaccumulation in marine organisms. Elsevier, Oxford

Newman MC (2015) Fundamentals of Ecotoxicology the science of pollution. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Ng JC (2005) Environmental contamination of arsenic and its toxicological impact on humans. Environ Chem 2:146–160

Nickson RT, McArthur JM, Ravenscroft R, Burgess WG, Ahmed KM (2000) Mechanism of arsenic release to groundwater, Bangladesh and West Bengal. Appl Geochem 15:403–413

Nordstrom DK (2002) Worldwide occurrences of arsenic in ground water. Science 296:2143–2145

Nriagu JO, Azcue JM (1990). In: Nriagu JO (ed) Arsenic in the environment. Part I: cycling and characterization. Wiley, New York, pp 1–15

Olguı´n EJ, Sa´nchez-Galva´n G (2012) Heavy metal removal in phytofiltration and phycoremediation: the need to differentiate between bioadsorption and bioaccumulation. New Biotechnol 30:3–8

Oliveira LHB, Ferreira NS, Oliveira A, Nogueira ARA, Gonzalez MH (2017) Evaluation of distribution and bioaccumulation of arsenic by ICP-MS in Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) cultivated in different environments. J Braz Chem Soc 28:2455–2463

Oremland RS, Stolz JF (2003) The ecology of arsenic. Science 300:939–944

Oremland RS, Stolz JF (2005) Arsenic, microbes and contaminated aquifers. Trends Microbiol 13:45–49

Páez-Espino D, Tamames J, de Lorenzo V, Cánovas D (2009) Microbial responses to environmental arsenic. Biometals 22:117–130

Passino DRM, Novak AJ (1984) Toxicity of arsenate and DDT to the cladoceran Bosmina longirostris. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 33:325–329

Penrose WR, Conacher HBS, Black R, Méranger JC, Miles W, Cunningham HM, Squires WR (1977) Implications of inorganic/ organic interconversion on fluxes of arsenic in marine food webs. Environ Health Persp 19:53–59

Peshut PJ, Morrison RJ, Brooks BA (2008) Arsenic speciation in marine fish and shellfish from American Samoa. Chemosphere 71:484–492

Peterson ML, Carpenter R (1983) Biogeochemical cycling processes affecting arsenic species in an intermittently anoxic fjord. Mar Chem 12:295–321

Punshon T, Jackson BP, Meharg AA, Warczack T, Scheckel K, Guerinot ML (2017) Understanding arsenic dynamics in agronomic systems to predict and prevent uptake by crop plants. Sci Total Environ 581:209–220

Qin J, Rosen BP, Zhang Y, Wang G, Franke S, Rensing C (2006) Arsenic detoxification and evolution of trimethylarsine gas by a microbial arsenite S-adenosylmethionine methyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:2075–2080

Rahman MA, Hasegawa H (2012) Arsenic in freshwater systems: influence of eutrophication on occurrence, distribution, speciation, and bioaccumulation. App Geochem 27:304–314

Rahman MA, Hasegawa H, Lim R (2012) Bioaccumulation, biotransformation and trophic transfer of arsenic in the aquatic food chain. Environ Res 116:118–135

Ravenscroft P, Brammer H, Richard KS (2009) Arsenic pollution: a global synthesis. Wiley-Blackwell

Ricevuto E, Lanzoni I, Fattorini D, Regoli F, Gambi MC (2016) Arsenic speciation and susceptibility to oxidative stress in the fanworm Sabella spallanzanii (Gmelin) (Annelida, Sabellidae) under naturally acidified conditions: an in situ transplant experiment in a Mediterranean CO2 vent system. Sci Total Environ 544:765–773

Ridley WP, Dizikes LJ, Wood JM (1977) Biomethylation of toxic elements in the environment. Science 197:329–332

Rodney E, Herrera P, Luxama J, Boykin M, Crawford A, Carroll MA, Catapane EJ (2007) Bioaccumulation and tissue distribution of arsenic, cadmium, copper and zinc in Crassostra virginica grown at two different depths in Jamaica Bay, New York. In Vivo 29:16–27

Rumpler A, Edmonds JS, Katsu M, Jensen KB, Goessler W, Raber G, Gunnlaugsdottir H, Francesconi KA (2008) Arsenic-containing long-chain fatty acids in cod-liver oil: a result of biosynthetic infidelity? Angew Chem 47:2665–2667

Sanders JG (1985) Arsenic geochemistry in Chesapeake Bay: dependence upon anthropogenic inputs and phytoplankton species composition. Mar Chem 17:329–340

Sanders JG (1986) Direct and indirect effects of arsenic on the survival and fecundity of estuarine zooplankton. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 43:694–699

Sanders JG, Cibilt SJ (1985) Adaptive behaviour of euryhaline phytoplankton communities to arsenic stress. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 22:199–205

Sanders JG, Osman RW, Riedel GF (1989) Pathways of arsenic uptake and incorporation in estuarine phytoplankton and the filter-feeding invertebrates Eurytemora affinis, Balanus improvisus and Crassostrea virginica. Mar Biol 103:319–325

Santosa SJ, Wada S, Tanaka S (1994) Distribution and cycle of arsenic compounds in the ocean. Appl Organomet Chem 8:273–283

Santosa SJ, Mokudai H, Takahashi M, Tanaka S (1996) The distribution of arsenic compounds in the ocean: biological activity in the surface zone and removal processes in the deep zone. Appl Organomet Chem 10:697–705

Sarmiento AM, Nieto JM, Casiot C, Elbaz-Poulichet F, Eqal M (2009) Inorganic arsenic speciation at river basin scales: the Tinto and Odiel rivers in the Iberian Pyrite Belt, SW Spain. Environ Pollut 157:1202–1209

Schaeffer R, Francesconi KA, Kienzl N, Soeroes C, Fodor P, Varadi L, Raml R, Goessler W (2006) Arsenic speciation in freshwater organisms from the river Danube in Hungary. Talanta 69:856–865

Schäfer S, Buchmeier G, Claus E et al (2015) Bioaccumulation in aquatic systems: methodological approaches, monitoring and assessment. Environ Sci Eur 27:5

Schmitt CJ, Brumbaugh WG (1990) National contaminant biomonitoring program: concentrations of arsenic, cadmium, copper, lead, mercury, selenium, and zinc in U.S. Freshwater Fish, 1976–1984. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 19:731–747

Schoof RA, Yager JW (2007) Variation of total and speciated arsenic in commonly consumed fish and seafood. Hum Ecol Risk Assess 13:946–965

Scott GR, Sloman KA (2004) The effects of environmental pollutants on complex fish behavior: integrating behavioral and physiological indicators of toxicity. Aquat Toxicol 68:369–392

Sele V, Sloth JJ, Lundebye AK, Larsen EH, Berntssen MHG, Amlund H (2012) Arsenolipids in marine oils and fats: a review of occurrence, chemistry and future research needs. Food Chem 133:618–630

Shah T (2019) Climate change and groundwater: India’s opportunities for mitigation and adaptation. Environ Res Lett 4:035005

Shaji E, Santosh M, Sarath KV, Prakash P, Deepchand V, Divya BV (2021) Arsenic contamination of groundwater: a global synopsis with focus on the Indian Peninsula. Geosci Front 12:101079

Shariatpanahi M, Anderson AC, Abdelghani AA, Englande AJ, Hughes J, Wilkinson RF (1981) Biotransformation of the pesticide sodium arsenate. J Environ Sci Health B 16:35–47

Sharma VK, Sohn M (2009) Aquatic arsenic: toxicity, speciation, transformations, and remediation. Environ Int 35:743–759

Shi K, Wang Q, Wang G (2020) Microbial oxidation of arsenite: regulation, chemotaxis, phosphate metabolism and energy generation. Front Microbiol 11:2235

Shibata Y, Morita M (1992) Characterization of organic arsenic compounds in bivalves. App Organomet Chem 6:343–349

Shiomi K, Kakehahi Y, Yamanaka H, Kikuchi T (1987) Identification of arsenobetaine and a tetramethylarsonium salt in the clam Meretrix lusoria. App Organomet Chem 1:177–183

Shrivastava A, Ghosh D, Dash A, Bose S (2015) Arsenic contamination in soil and sediment in India: sources, effects, and remediation. Curr Poll Rep 1:35–46

Šlejkovec Z, Bajc Z, Doganoc DZ (2004) Arsenic speciation patterns in freshwater fish. Talanta 62:931–936

Šlejkovec Z, Stajnko A, Falnoga I, Lipej L, Mazej D, Horvat M, Faganeli J (2014) Bioaccumulation of arsenic species in Rays from Northern Adriatic Sea. Int J Mol Sci 15:22073–22091

Sloth JJ, Julshamn K (2008) Survey of total and inorganic arsenic content in blue mussels (Mytilus edulis L.) from Norwegian fiords: revelation of unusual high levels of inorganic arsenic. J Agric Food Chem 56:1269–1273

Smedley PL, Kinniburgh DG (2002) A review of the source, behaviour and distribution of arsenic in natural waters. Appl Geochem 17:517–568