Abstract

Background

Post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) is the long-lasting impairment of physical functions, cognitive functions, and mental health after intensive care. Although a long-term follow-up is essential for the successful management of PICS, few reviews have summarized evidence for the efficacy and management of the PICS follow-up system.

Main text

The PICS follow-up system includes a PICS follow-up clinic, home visitations, telephone or mail follow-ups, and telemedicine. The first PICS follow-up clinic was established in the U.K. in 1993 and its use spread thereafter. There are currently no consistent findings on the efficacy of PICS follow-up clinics. Under recent evidence and recommendations, attendance at a PICS follow-up clinic needs to start within three months after hospital discharge. A multidisciplinary team approach is important for the treatment of PICS from various aspects of impairments, including the nutritional status. We classified face-to-face and telephone-based assessments for a PICS follow-up from recent recommendations. Recent findings on medications, rehabilitation, and nutrition for the treatment of PICS were summarized.

Conclusions

This narrative review aimed to summarize the PICS follow-up system after hospital discharge and provide a comprehensive approach for the prevention and treatment of PICS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since advances in critical care have improved survival rates, long-term management has gradually been highlighted to restore the functional capabilities of intensive care unit (ICU) survivors [1]. Post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) is the long-lasting impairment of physical functions, cognitive functions, and mental health after intensive care [1]. A previous study reported that 56% of patients exhibited some impairment in one of the three components of PICS in the 12 months after hospital discharge [2]. Furthermore, 40% of pre-employed ICU survivors were unable to return to work 12 months after hospital discharge [3]. PICS may persist for more than 10 years after discharge [4].

Although numerous bundles are often implemented to prevent PICS, the interventions employed during hospital stays are insufficient to prevent PICS [5, 6]. Therefore, a long-term follow-up is essential for the successful management of PICS [7]. One strategy is a PICS follow-up system with a multi-disciplinary team [8, 9]. A PICS follow-up clinic provides PICS evaluations, follow-ups, and treatments through the expertise of each specialized member, while telephone-based interviews allow for remote follow-ups [9]. There are various ways for this PICS follow-up systems.

Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses reported the importance of PICS follow-up system [10, 11]. However, few reviews summarized the detail of follow-up system, assessment methods, and contents of management. This information is essential to launch the PICS follow-up system in each facility. Therefore, we summarized the history of and evidence for the PICS follow-up system and its management. In this review, we used the term “PICS follow-up system” as comprehensive system including telephone and online, and the term “PICS follow-up clinic” as the outpatient clinic.

History of PICS follow-up clinics

PICS follow-up clinics are called “PICS clinics”, “ICU follow-up clinics”, or “ICU recovery centers” [12,13,14]. The first PICS follow-up clinic, “Intensive after care after intensive care”, started at a London hospital in 1993 [8]. Physicians and nurses in the U.K. began following long-term outcomes after critical illnesses. The international conference “Surviving Intensive Care” held in Brussels in 2002 stated that ICU survivors need to be followed up for more than six months. A PICS follow-up clinic was proposed as an approach to evaluate ICU survivors and their families’ long-term outcomes [15]. In 2006, PICS follow-up clinics were available in 30% of U.K. ICUs [16]. PICS follow-up clinics that are mostly managed by nurses have since increased in the U.K. [17] and Sweden [18].

In the U.S., the first PICS follow-up clinic started in 2011 [19] after the Society of Critical Care Medicine proposed the PICS concept in 2010 [1]. The Society of Critical Care Medicine THRIVE collaboratives, the group working for Post-ICU Clinic and Peer Support, globally provided ICU survivors and their families with education, community, and quality improvement [20, 21]. Furthermore, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in 2017 recommended that “Adults who stayed in critical care for more than 4 days and were at risk of morbidity have a review 2 to 3 months after discharge from critical care” [22].

In contrast, PICS follow-up clinics are not common in Japan. In Japan, the first hospital-scale PICS follow-up clinic opened in Ibaraki prefecture at 2019 [12]. The PICS committee of the Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine conducted a questionnaire survey in 2021, and reported that PICS follow-up clinics were only conducted in 4% (4/110) of ICUs [23]. Therefore, further recognition of the importance of PICS follow-up clinics is needed.

PICS follow-up clinic management

Evidence for the efficacy of PICS follow-up clinics

Scientific evidence for the efficacy of PICS follow-up clinics is limited. A randomized controlled trial on PICS follow-up clinics at three U.K. hospitals found no significant differences in quality of life (QOL) one year after ICU discharge or medical costs [24]. Furthermore, in another randomized controlled trial on ICU follow-up clinics, health-related QOL was not improved in ICU survivors with type 2 diabetes [25]. Therefore, a Cochrane review summarized 4 randomized controlled trials and concluded that PICS follow-up clinic interventions did not provide sufficient evidence on functional impairment outcomes [26]. However, a meta-analysis that summarized 16 PICS follow-up clinic interventions found that physical therapy prevented depression and the reduction in QOL, while psychological interventions improved posttraumatic stress disorder [10]. Although it is based on weak recommendations, Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines 2021 recommends a post-discharge assessment and follow-up of physical function, cognitive function, and mental health in patients with sepsis or septic shock [27]. Differences in recommendations among studies are due to the timing of interventions and their contents. Organized multidisciplinary interventions may change the evidence of PICS follow-up clinics.

Practice of PICS follow-up systems

The desirable timing for a follow-up has not yet been clarified. Previous studies reported that the PICS follow-up clinic needs to be attended by patients within one to three months after hospital discharge because PICS develops early after hospital discharge [12, 24, 28]. The Society of Critical Care Medicine and Dutch guidelines recommend that high-risk patients need to be screened 2–4 weeks after hospital discharge and followed up at 6–12 weeks after hospital discharge [29, 30]. Physical dysfunction and muscle weakness have been reported even during ICU stays [31], and cognitive dysfunction and mental health issues are also common in the early course of critical illness [32,33,34]. A follow-up needs to be conducted at multiple times every few months. In a systematic review, it was common to follow-up patients after 3, 6, and 12 months [35]. Long-term follow-ups are also needed because PICS has been reported in more than 50% of ICU survivors 12 months after discharge [36, 37].

The various methods used for a follow-up. Follow-up systems for critically ill patients after discharge from the ICU include PICS follow-up clinics, visitations to the patient’s home or facility, questionnaires posted by mail or in an e-mail to the patient’s home, and telephone or internet-based telemedicine. Although they are important, it is difficult for severely ill ICU survivors to visit PICS follow-up clinics. Therefore, an assessment through a telephone interview or online may be selected. In a previous study, nurse-led home or facility visitation within 8 weeks of hospital discharge reduced the length of readmission days by approximately 6 days [38]. Home visitation may lead to direct interventions. However, home-based interventions require further study because a previous study showed that physical therapist-led 8-week home-based exercise rehabilitation did not contribute to the recovery of physical functions [39]. A questionnaire evaluation via an e-mail has a lower response rate than that posted in the mail, but is 10 times more cost-effective and has fewer missing values [40]. A telephone-based follow-up is often used to screen patients requiring a follow-up [41]. In a previous study, 93% of patients preferred telephone follow-ups over face-to-face follow-ups [42]. Other studies conducted nurse-led monthly phone calls for sepsis survivors 6 months after discharge or a psychologist-led mindfulness program 6 weeks after discharge [43, 44]. The findings obtained showed that neither of the telephone-based interventions improved the QOL of ICU survivors. Internet-based telemedicine is more convenient and time efficient than visitations [45]. A systematic review on the PICS follow-up system revealed that telemedicine models of post-ICU care increased recruitment rates, intervention implementation success rates, and participant retention rates [11]. However, its impact on clinical outcomes warrants further investigation.

It is important to choose the population for ICU follow-up clinics because of limited workforce and time allocation. The target population for ICU follow-up clinics should be the patients with high risk of exhibiting PICS, such as patients with prolonged ICU stays, patients requiring ventilatory management, septic patients, patients with delirium, patients with high severity of illness such as APACHE2 and SOFA scores, women, and elderly patients [12, 25, 36, 46,47,48]. A 2018 literature review on outpatient ICU follow-up clinics suggested that eligible patients should be on ventilator management for at least 48 h or an ICU stay of at least 3–5 days, but less than 20% of these patients are actually followed up [41]. There is still insufficient evidence for optimal follow-up population and further data accumulation is needed.

Due to the wide number of PICS symptoms, it is important to provide a multidisciplinary team approach in PICS follow-up clinics with physicians, nurses, physical therapists, pharmacists, clinical psychologists, and dietitians (Fig. 1) [49]. Physicians are responsible for medical examinations, prescriptions, and consultations [43]. Nurses often play a central role in PICS follow-up clinics [12]. Physical therapists evaluate physical functions and provide rehabilitation [9]. Pharmacists contribute to medication management and the identification of adverse drug risks as well as preventive interventions, such as vaccinations [50, 51]. Clinical psychologists evaluate mental health and provide preventive measures for psychiatric symptoms [9, 52]. Dietitians evaluate the nutritional status and provide nutritional education, including oral nutritional supplements and dietary menu arrangements [53].

Positions and roles in the PICS follow-up clinic. In the PICS follow-up clinic, physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, dietitians, pharmacists, and psychologists play specialized roles in the management of patients with PICS and their families. The clinic aims to reintegrate PICS patients and their families back into society through the importance of multidisciplinary cooperation

PICS assessment instruments

PICS assessment in PICS follow-up system

The PICS assessment is the initial step in follow-up of ICU survivors, which allows us for a precise evaluation of their conditions and facilitates intervention to enhance their well-being. However, there are too many instruments available for assessing PICS, and as of now, they lack standardization [35, 54]. Previously, various expert groups have recommended distinct sets of tools, including over 30 recommended PICS assessment instruments (Table 1) [29, 35, 55,56,57]. An appropriate selection is required for different follow-up methods such as face-to-face, telephone, and online questionnaires. We can consider the frequency of usage in previous literature (as shown in Table 1) for the selection process, because instruments that are frequently used are suitable for comparing performance across facilities, and are often deemed valid and user-friendly.

The standard method for follow-up in the PICS clinic is face-to-face assessment, where we can use all the instruments listed in Table 1. An intensive care group in Germany proposed an approach starting from screening of PICS symptoms in outpatient settings [57]. For the screening, they recommended handgrip strength and the Timed Up-and-Go test for physical function, MiniCog and Animal Naming for cognition, PHQ-4 for mental health, and EQ-5D for health-related QOL. These instruments are very simple and highly sensitive, which are suited for screening. However, they exhibit relatively low specificity, necessitating extended evaluation. For example, the PHQ-4, with only four included items, has reported sensitivity and specificity of 0.90 and 0.61 for depression, and 0.88 and 0.61 for anxiety, respectively [58]. Alternatively, we can use other instruments that are slightly more time-consuming but offer greater specificity. These include 6-min walk test and MRC score for physical function, MoCA and MMSE for cognition, HADS and IES-R for mental health, and SF-36 for health-related QOL. These instruments have modest sensitivity and relatively high specificity. For example, HADS, with 14 included items, has reported sensitivity and specificity of 0.74 and 0.84 for depression, and 0.70 and 0.79 for anxiety, respectively [59, 60]. If these tools yield positive results, further evaluation should be considered by a multidisciplinary team, including professionals such as psychiatrists and physiotherapists. There is limited literature comparing diagnostic performance between instruments in patients with PICS. Therefore, the choice of instruments in the PICS clinic should align with the specific purpose and available resources.

PICS is also challenging for a patient’s family members and is assessed using PICS-family [61]. SF-36, HADS, and IES-R are recommended for the evaluation of PICS-family [35]. Furthermore, the concept of PICS was recently expanded from three main domains (physical, cognitive, and mental issues) to other domains, such as sleep disorders and chronic pain [7]. The Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine PICS committee has highlighted the importance of these insights, and recommends the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index for sleep disorders and Brief Pain Inventory for pain [35].

Nutrition therapy is one of the promising interventions for PICS after discharge. In the assessment of nutritional interventions, an international nutritional and metabolic group recommended the 30-s sit-to-stand test and the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) for the nutrition status as essential components of the Outcome Set [55]. Furthermore, assessments of frailty and body composition are recommended, including an evaluation of muscle mass [62]. Frailty may be analyzed using the Clinical frailty scale (CFS) [63].

Muscle mass assessment as a body composition analysis is important in a PICS clinic to evaluate the nutritional status and physical function. Skeletal muscle mass in ICU survivors may be examined by validated methods, such as ultrasound or bioelectrical impedance analysis. Although dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry or CT can be used in the muscle mass assessment, these equipment and high cost hinder its routine use in PICS follow-up clinic [64, 65]. Ultrasound is non-invasive, but sufficient skills are needed for an accurate assessment [66]. A bioelectrical impedance analysis is non-invasive and not affected by inter-rater variability; however, fluid changes in some patients, may have an impact on the results obtained [67]. Muscle mass assessment is important, but there are still barriers to its implementation in PICS follow-up clinic. Particularly, it is difficult to implement in a telephone interview and online questionnaires, requiring future studies in this field.

PICS assessment through a telephone interview and online questionnaires

Some ICU survivors cannot physically attend the PICS clinic and require follow-up through telephone interviews or online questionnaires. To evaluate these patients, we can use instruments available with telephone interview-style or self-report methods as listed in Table 1. The majority of instruments to assess mental health, QOL, and ADL may be used in a telephone interview, whereas physical and cognitive functions are often difficult to evaluate without visitation. Some instruments are available for telephone-based physical assessments. Health-related QOL may be examined through a telephone interview, and the physical component score of SF-36 or mobility, self-care, and usual activities of EQ-5D-5L are recommended for screening physical impairments as a part of health-related QOL [29, 55]. SF-12 (the short version of SF-36) is a useful instrument for calculating the physical component score of health-related QOL due to its simplicity [35]. Telephone-based ADL assessments including the Barthel Index may be useful for analyzing physical domains because ADL includes physical function as well as cognitive function. In previous studies, frailty was examined using CFS via a telephone interview [68, 69]. Since 40% of ICU survivors reported an increase in frailty after discharge [42], CFS may be useful to assess the physical domain [69].

Regarding cognitive functions, previous studies showed that a cognitive assessment through a telephone interview was not inferior to that in a face-to-face assessment [70, 71]. A telephone version of MoCA, termed T-MoCA, is conducted through a telephone interview [72]. This T-MoCA score may be changed into MoCA. MMSE also has a telephone version [73]. Self-reported methods are optional for an assessment of cognitive function, which may be evaluated through the telephone as well as online or in posted questionnaires. The Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine PICS committee recommends the Short Memory Questionnaire as a self-reported method for cognition, which may also be assessed by family caregivers [35]. In the absence of a dedicated PICS clinic, a telephone follow-up may be an option for ICU survivors.

PICS treatment interventions

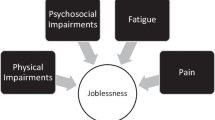

PICS treatment interventions mainly consist of medication, rehabilitation, and nutrition therapy. These interventions need to be provided by a multidisciplinary team (Fig. 2). Details on medication, rehabilitation, and nutrition therapy are summarized as follows.

Interventions in the PICS follow-up system after discharge. Patients recovering from critical illness may receive interventions from medical staff in some PICS follow-up systems, in which the PICS follow-up clinic functions as the center. These systems may consist of a multi-disciplinary team for various approaches to PICS. They mainly provide patients with interventions involving medication, rehabilitation, and nutrition therapy based on a PICS evaluation in the same system

Medication approach

Two primary components are important for a medication approach: adjustments and interventions. Polypharmacy is common in critically ill patients due to the wide variety of symptoms [74]. Polypharmacy has been identified as a risk factor for readmission in ICU survivors [75]. Therefore, medication adjustments are needed after intensive care [76]. Furthermore, pharmacological interventions may be helpful for recovery from PICS [77]. Although some medications have been suggested to promote patient recovery, concrete evidence is insufficient [78].

A previous study revealed the prevalence of medication-related issues in PICS follow-up clinics. A PICS follow-up clinic survey in Scotland revealed that more than 60% of ICU survivors between 4 and 12 weeks after hospital discharge required interventions due to medication-related issues [79]. New medications started during the ICU stay are often the cause of intolerable side effects [80]. The most commonly discontinued and unnecessary medications in PICS follow-up clinics were proton pump inhibitors (19%), anticoagulants (12%), non-opioid pain analgesics (10%), and antipsychotics (7%) because they caused complications, such as an altered mental state, excessive sedation, and bleeding [50].

To achieve effective medication adjustments, the integration of pharmacists into a multidisciplinary follow-up team is a unique and invaluable contribution. Pharmacists may address drug interactions and adjustments for patients with impaired organ functions [81]. After ICU discharge, 9% of patients required an increased dose of or newly started sedatives or antipsychotics for their mental symptoms [50]. It is desirable for the same pharmacist to manage medications during and after ICU care because this provides a coherent approach from inpatient to outpatient settings [50]. A previous study reported that an intervention by pharmacists in a PICS follow-up clinic decreased the prevalence of medication-related issues [82].

Pharmacological interventions have been desired for some PICS components; however, there is insufficient evidence for its clinical application. The intervention to muscle protein synthesis, such as oxandrolone [78] or myostatin inhibitor [83], might enhance the recovery of physical impairments. A randomized controlled trial showed oxandrolone reduced muscle atrophy during the acute phase postburn [84], but the US Food and Drug Administration withdrew the medicine due to its complications (e.g., hepatitis, atherosclerosis, and malignancy) [85]. On the other hand, myostatin inhibitor modulated muscle atrophy and weakness [83], but the effect is not confirmed in clinical trials. Contrary to the physical impairments, few medications are effective for cognitive impairments and mental health even in the acute phase. Further researches are needed to develop medications for PICS treatment.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation after hospital discharge is crucial to aggressively regain functions for the reintegration of patients into their communities, in contrast to its preventive meaning in the acute phase of a critical illness. The urgency for effective post-discharge rehabilitation programs has grown in tandem with the increase in survival rates for various critical diseases in the ICU. Post-discharge rehabilitation comprises different types of interventions, including physical therapy, respiratory muscle training, swallowing exercises, occupational therapy, cognitive rehabilitation, and mental care (Fig. 3). Besides a multidisciplinary approach [86], the involvement of caregivers or family members has been shown to enhance the effects of the program through appropriate education and training as well as an understanding of their post-ICU life [87]. Education is important for successful adherence to rehabilitation [88, 89]. It provides essential support for patients, ensures their exercise adherence, and promptly identifies any complications.

A one-size-fits-all approach often falls short in addressing the needs of each patient [24]. Elliott et al. demonstrated that the application of a uniform physical rehabilitation program with five 1-h home visits at home and three telephone follow-ups for 8 weeks did not improve physical function [39]. In contrast, a 2-h rehabilitation program per week for the first 6 weeks, involving tailored supervision and education, increased walk distances [90]. The lack of a consensus on the intensity, frequency, or even contents of rehabilitation programs consistently emphasize the importance of personalized treatment plans based on thorough patient assessments in the follow-up period [91]. Individualized programs tailored for each patient represents the only approach to successfully meet individual needs and enhance both effectiveness and patient adherence, thereby leading to efficient and effective improvements in their post-ICU life [92, 93]. In this context, particularly for patients with no transportation methods or access to the facility, home-based rehabilitation has been reported to offer similar outcomes to institution-based programs [94]. These programs facilitate adherence by eliminating transportation barriers, providing familiar environments, and often having higher patient acceptance rates. In addition, the incorporation of the telerehabilitation system into these home-based programs allows for remote assessments, guidance, and monitoring by professionals, ensuring the continuity of care even when in-person sessions are not feasible [95]. These approaches may not only be cost-effective and expand access to specialized care for those in geographically distant areas, but also have the potential to provide rehabilitation programs after hospital discharge in future pandemics when isolation and strict infection regulations are in place.

Nutrition therapy

Nutrition therapy is an essential support for the recovery of critically ill patients. From the viewpoint of muscle protein synthesis, adequate energy and protein provision is vital for maintaining and restoring muscle volume, which is linked to physical performance [96]. More nutritional support than usual is required after discharge as the convalescent period. As critical care nutrition guidelines have not addressed the details of nutritional support during this period [97, 98], there is lack of evidence regarding actual energy expenditure. Besides the perspective of disease complications and anabolic resistance, expert opinions indicate that 35 kcal/kg/day and 2.0–2.5 g/kg/day of protein are good targets during this period after discharge [99].

Nutritional intake after intensive care decreases to 30–50% of the optimal intake due to the end of enteral tube feeding [100,101,102]. This decreased nutritional intake continues after hospital discharge at 70% of the optimal nutritional intake even one year after discharge [103]. An insufficient nutritional intake was found to be dependent on the severity of prolonged physical impairments [104]. One of the main reasons for a decreased nutrition intake is a prolonged loss of appetite [105]. Abdominal swelling, nausea, vomiting, and tasting disorders contribute to a prolonged loss of appetite [102]. Prolonged depression and anxiety also decrease appetite [106]. Dysphagia, which occurs in 80% of ICU patients, persists in up to 60% of patients in the convalescent period [107, 108]. Therefore, malnutrition after ICU discharge is a serious issue that requires nutrition therapy interventions [53]. However, few studies have investigated nutritional interventions after hospital discharge. Salisbury et al. randomized patients with/without active rehabilitation, with continued nutritional support after discharge, but did not find any significant difference in physical outcomes [103]. However, calorie and protein intakes three months after discharge from the ICU were higher in the active rehabilitation group; 113.4% (71.9%–113.4%) vs. 70.0% (63.1%–95.9%) in energy and 90.3% (72.7%–126.1%) vs. 68.7% (61.9%–93.9%) in protein as percentages of estimated requirements. In this study, they primarily aimed at establishing the feasibility of these interventions and concluded that this type of post-discharge nutritional intervention was feasible.

Although there are currently no concrete recommendations for nutritional interventions, one possibility is the use of oral nutrition supplements. Since oral nutrition supplements are available in various tastes and smells with different amounts of protein, energy, and specific nutrients, dieticians may prescribe oral nutrition supplements based on a patient’s needs and preferences. Ridley et al. reported that patients receiving oral nutrition supplements had higher optimal energy and protein administration (73% and 68%, respectively) than those not receiving oral nutrition supplements (37% and 48%, respectively) [100]. Oral nutritional supplements need to be prescribed by dietitians to achieve optimal nutritional requirements [109]. There are currently no specific nutrient recommendations, including those for leucine, glutamine, arginine, carnitine, vitamin D, or ω3 fatty acids, due to the lack of significant findings and studies on PICS populations [98, 110]. β-Hydroxy β-methylbutyrate, a muscle protein synthesis stimulator, has potential as a nutritional intervention to gain muscle mass after discharge under a high protein supplement [111, 112].

Future directions to treat PICS after discharge

Since PICS is an important social issue, health care workers need to monitor PICS after hospital discharge for its prevention [15]. However, the PICS follow-up system is not common. One of the important reasons for this is insufficient funding. Among facilities in the U.K., 90% did not receive funding and managed PICS follow-up clinics with own ICU budget [16]. There is currently no support for PICS follow-up clinics by the national health insurance systems in any country [41]. In the U.K., 90% of facilities without PICS follow-up clinics reported insufficient funding as the barrier [16]. In Japan, the Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine has now submitted a request to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, with the aim of creating national health insurance support for a PICS follow-up system. This type of financial support will accelerate PICS follow-ups.

Another barrier is insufficient evidence for the efficacy of the PICS follow-up system; therefore, patients cannot expect to receive benefits [16]. There are currently few intervention studies on the post-discharge phase, as discussed in this review. In contrast to the length of ICU stays, the duration after hospital discharge is sufficiently long to treat PICS. Therefore, a randomized controlled trial on interventions is needed. Due to the lack of adequate evidence, there are numerous possible interventions after hospital discharge, which include rehabilitation and nutritional interventions of different frequencies and degrees. Furthermore, the use of some drugs and patient care need to be investigated in future studies. PICS follow-up may play a leading role in this type of study.

The last barrier for the PICS follow-up system is the lack of recognition of PICS concept in not only patients and ICU workers, but also in the staffs in their hospitals and the other medical institutions outside hospitals. Awareness and education across and beyond each ICU and hospital have been argued as necessary from the PICS proposal era [1], nevertheless, the 2022 facility survey in our country revealed that the lack of understanding by the hospitals (71.8%), knowledges in ICU staffs (61.8%) and understandings by hospital administrator (53.6%) were raised as the barriers to perform PICS follow-up [23]. To promote the PICS follow-up system, we should return to the origin to expand much more awareness and education besides the financial support and evidences establishment.

Under the current widespread use of information technology, remote follow-up systems are expected to make a significant contribution to PICS follow-ups after hospital discharge. Besides conventional telephone interviews and mailed questionnaires, telemedicine is considered a new form of PICS follow-up clinic [113]. In a recent study, a telemedicine-through follow-up was well accepted by ICU survivors and their caregivers [45]. Telemedicine was also more readily accepted among pediatric populations and their families [114, 115]. The recent COVID-19 pandemic accelerated telemedicine technology, which has produced positive results [116, 117]. Some technologies require information technology literacy by both patients and health care workers, and future PICS follow-ups will require information technology-enabled ideas and flexibility.

Conclusions

This review summarized the PICS follow-up system after hospital discharge and provides a comprehensive approach for the prevention and treatment of PICS. Although PICS assessments and follow-up methods vary, a multidisciplinary team approach is essential for the successful management of PICS.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- PICS:

-

Post-intensive care syndrome

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- MoCA:

-

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- IES-R:

-

Impact of Event Scale-Revised

- SF-36:

-

Short Form-36

- EQ-5D:

-

European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions

- ADL:

-

Activity of daily living

- GLIM:

-

Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition

- CFS:

-

Clinical frailty scale

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 19

References

Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, Hopkins RO, Weinert C, Wunsch H, Zawistowski C, Bemis-Dougherty A, Berney SC, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:502–9.

Marra A, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Patel MB, Hughes CG, Jackson JC, Thompson JL, Chandrasekhar R, Ely EW, Brummel NE. Co-occurrence of post-intensive care syndrome problems among 406 survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:1393–401.

Kamdar BB, Suri R, Suchyta MR, Digrande KF, Sherwood KD, Colantuoni E, Dinglas VD, Needham DM, Hopkins RO. Return to work after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2020;75:17–27.

Ramnarain D, Aupers E, den Oudsten B, Oldenbeuving A, de Vries J, Pouwels S. Post Intensive Care Syndrome (PICS): an overview of the definition, etiology, risk factors, and possible counseling and treatment strategies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2021;21:1159–77.

Fuke R, Hifumi T, Kondo Y, Hatakeyama J, Takei T, Yamakawa K, Inoue S, Nishida O. Early rehabilitation to prevent postintensive care syndrome in patients with critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8: e019998.

Ullman AJ, Aitken LM, Rattray J, Kenardy J, Le Brocque R, MacGillivray S, Hull AM. Diaries for recovery from critical illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014: Cd010468.

Rousseau AF, Prescott HC, Brett SJ, Weiss B, Azoulay E, Creteur J, Latronico N, Hough CL, Weber-Carstens S, Vincent JL, et al. Long-term outcomes after critical illness: recent insights. Crit Care. 2021;25:108.

Waldmann CS. Intensive after care after intensive care. Curr Anaesth Crit Care. 1998;9:134–9.

Sevin CM, Bloom SL, Jackson JC, Wang L, Ely EW, Stollings JL. Comprehensive care of ICU survivors: development and implementation of an ICU recovery center. J Crit Care. 2018;46:141–8.

Rosa RG, Ferreira GE, Viola TW, Robinson CC, Kochhann R, Berto PP, Biason L, Cardoso PR, Falavigna M, Teixeira C. Effects of post-ICU follow-up on subject outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care. 2019;52:115–25.

Dimopoulos S, Leggett NE, Deane AM, Haines KJ, Abdelhamid YA. Models of intensive care unit follow-up care and feasibility of intervention delivery: a systematic review. Aust Crit Care. 2023;S1036–7314:00060–7.

Nakamura K, Kawasaki A, Suzuki N, Hosoi S, Fujita T, Hachisu S, Nakano H, Naraba H, Mochizuki M, Takahashi Y. Grip strength correlates with mental health and quality of life after critical care: a retrospective study in a post-intensive care syndrome clinic. J Clin Med. 2021;10:3044.

Bottom-Tanzer SF, Poyant JO, Louzada MT, Ahmed SE, Boudouvas A, Poon E, Hojman HM, Bugaev N, Johnson BP, Van Kirk AL, et al. High occurrence of postintensive care syndrome identified in surgical ICU survivors after implementation of a multidisciplinary clinic. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;91:406–12.

Schmidt KFR, Gensichen J, Gehrke-Beck S, Kosilek RP, Kühne F, Heintze C, Baldwin LM, Needham DM. Management of COVID-19 ICU-survivors in primary care: a narrative review. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22:160.

Angus DC, Carlet J, Brussels Roundtable P. Surviving intensive care: a report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:368–77.

Griffiths JA, Barber VS, Cuthbertson BH, Young JD. A national survey of intensive care follow-up clinics. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:950–5.

Williams TA, Leslie GD. Beyond the walls: a review of ICU clinics and their impact on patient outcomes after leaving hospital. Aust Crit Care. 2008;21:6–17.

Engstrom A, Andersson S, Soderberg S. Re-visiting the ICU Experiences of follow-up visits to an ICU after discharge: a qualitative study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2008;24:233–41.

Huggins EL, Bloom SL, Stollings JL, Camp M, Sevin CM, Jackson JC. A clinic model: post-intensive care syndrome and post-intensive care syndrome-family. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2016;27:204–11.

Haines KJ, Sevin CM, Hibbert E, Boehm LM, Aparanji K, Bakhru RN, Bastin AJ, Beesley SJ, Butcher BW, Drumright K, et al. Key mechanisms by which post-ICU activities can improve in-ICU care: results of the international THRIVE collaboratives. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:939–47.

After the ICU. https://www.sccm.org/MyICUCare/THRIVE.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Rehabilitation after critical illness in adults. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs158. Accessed 7 Sept 2017.

Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine. A questionnaire survey regarding follow-up after ICU discharge in Japan. J Jpn Soc Intensive Care Med. 2022;29:165–76.

Cuthbertson BH, Rattray J, Campbell MK, Gager M, Roughton S, Smith A, Hull A, Breeman S, Norrie J, Jenkinson D, et al. The PRaCTICaL study of nurse led, intensive care follow-up programmes for improving long term outcomes from critical illness: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339: b3723.

Ali Abdelhamid Y, Phillips LK, White MG, Presneill J, Horowitz M, Deane AM. Survivors of intensive care with type 2 diabetes and the effect of shared-care follow-Up clinics: the SWEET-AS randomized controlled pilot study. Chest. 2021;159:174–85.

Schofield-Robinson OJ, Lewis SR, Smith AF, McPeake J, Alderson P. Follow-up services for improving long-term outcomes in intensive care unit (ICU) survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:Cd012701.

Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, Machado FR, McIntyre L, Ostermann M, Prescott HC, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:1181–247.

Mayer KP, Ortiz-Soriano VM, Kalantar A, Lambert J, Morris PE, Neyra JA. Acute kidney injury contributes to worse physical and quality of life outcomes in survivors of critical illness. BMC Nephrol. 2022;23:137.

Mikkelsen ME, Still M, Anderson BJ, Bienvenu OJ, Brodsky MB, Brummel N, Butcher B, Clay AS, Felt H, Ferrante LE, et al. Society of critical care medicine’s international consensus conference on prediction and identification of long-term impairments after critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:1670–9.

Van Der Schaaf M, Bakhshi-Raiez F, Van Der Steen M, Dongelmans DA, De Keizer NF. Recommendations for intensive care follow-up clinics; report from a survey and conference of Dutch intensive cares. Minerva Anestesiol. 2015;81:135–44.

Nakanishi N, Oto J, Tsutsumi R, Akimoto Y, Nakano Y, Nishimura M. Upper limb muscle atrophy associated with in-hospital mortality and physical function impairments in mechanically ventilated critically ill adults: a two-center prospective observational study. J Intensive Care. 2020;8:87.

Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Matté A, Barr A, Mehta S, Mazer CD, Guest CB, Stewart TE, et al. Two-year outcomes, health care use, and costs of survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:538–44.

Honarmand K, Lalli RS, Priestap F, Chen JL, McIntyre CW, Owen AM, Slessarev M. Natural history of cognitive impairment in critical illness survivors. A systematic review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:193–201.

Galatzer-Levy IR, Huang SH, Bonanno GA. Trajectories of resilience and dysfunction following potential trauma: a review and statistical evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;63:41–55.

Nakanishi N, Liu K, Kawauchi A, Okamura M, Tanaka K, Katayama S, Mitani Y, Ota K, Taito S, Fudeyasu K, et al. Instruments to assess post-intensive care syndrome assessment: a scoping review and modified Delphi method study. Crit Care. 2023;27:430.

Mayer KP, Boustany H, Cassity EP, Soper MK, Kalema AG, Hatton Kolpek J, Montgomery-Yates AA. ICU recovery clinic attendance, attrition, and patient outcomes: the impact of severity of illness, gender, and rurality. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2: e0206.

Maley JH, Brewster I, Mayoral I, Siruckova R, Adams S, McGraw KA, Piech AA, Detsky M, Mikkelsen ME. Resilience in survivors of critical illness in the context of the survivors’ experience and recovery. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1351–60.

Douglas SL, Daly BJ, Kelley CG, O’Toole E, Montenegro H. Chronically critically ill patients: health-related quality of life and resource use after a disease management intervention. Am J Crit Care. 2007;16:447–57.

Elliott D, McKinley S, Alison J, Aitken LM, King M, Leslie GD, Kenny P, Taylor P, Foley R, Burmeister E. Health-related quality of life and physical recovery after a critical illness: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial of a home-based physical rehabilitation program. Crit Care. 2011;15:R142.

Ebert JF, Huibers L, Christensen B, Christensen MB. Paper- or web-based questionnaire invitations as a method for data collection: cross-sectional comparative study of differences in response rate, completeness of data, and financial cost. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20: e24.

Teixeira C, Rosa RG. Post-intensive care outpatient clinic: is it feasible and effective? A literature review. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2018;30:98–111.

Hodalova S, Moore S, Dowds J, Murphy N, Martin-Loeches I, Broderick J. Feasibility of telephone follow-up after critical care discharge. Med Sci (Basel). 2020;8:16.

Schmidt K, Worrack S, Von Korff M, Davydow D, Brunkhorst F, Ehlert U, Pausch C, Mehlhorn J, Schneider N, Scherag A, et al. Effect of a primary care management intervention on mental health-related quality of life among survivors of sepsis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:2703–11.

Cox CE, Porter LS, Buck PJ, Hoffa M, Jones D, Walton B, Hough CL, Greeson JM. Development and preliminary evaluation of a telephone-based mindfulness training intervention for survivors of critical illness. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:173–81.

Kovaleva MA, Jones AC, Kimpel CC, Lauderdale J, Sevin CM, Stollings JL, Jackson JC, Boehm LM. Patient and caregiver experiences with a telemedicine intensive care unit recovery clinic. Heart Lung. 2023;58:47–53.

Torres J, Carvalho D, Molinos E, Vales C, Ferreira A, Dias CC, Araújo R, Gomes E. The impact of the patient post-intensive care syndrome components upon caregiver burden. Med Intensiva. 2017;41:454–60.

Yang T, Li Z, Jiang L, Wang Y, Xi X. Risk factors for intensive care unit-acquired weakness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018;138:104–14.

De Jonghe B, Sharshar T, Lefaucheur JP, Authier FJ, Durand-Zaleski I, Boussarsar M, Cerf C, Renaud E, Mesrati F, Carlet J, et al. Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit: a prospective multicenter study. JAMA. 2002;288:2859–67.

van Sleeuwen D, van de Laar FA, Simons K, van Bommel D, Burgers-Bonthuis D, Koeter J, Bisschops LLA, Vloet L, Brackel M, Teerenstra S, et al. MiCare study, an evaluation of structured, multidisciplinary and personalised post-ICU care on physical and psychological functioning, and quality of life of former ICU patients: a study protocol of a stepped-wedge cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2022;12: e059634.

Stollings JL, Poyant JO, Groth CM, Rappaport SH, Kruer RM, Miller E, Whitten JA, McIntire AM, McDaniel CM, Betthauser KD, et al. An international, multicenter evaluation of comprehensive medication management by pharmacists in ICU recovery centers. J Intensive Care Med. 2023;38:957–65.

Stollings JL, Bloom SL, Wang L, Ely EW, Jackson JC, Sevin CM. Critical care pharmacists and medication management in an ICU recovery center. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52:713–23.

Peris A, Bonizzoli M, Iozzelli D, Migliaccio ML, Zagli G, Bacchereti A, Debolini M, Vannini E, Solaro M, Balzi I, et al. Early intra-intensive care unit psychological intervention promotes recovery from post traumatic stress disorders, anxiety and depression symptoms in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2011;15:R41.

Moisey LL, Merriweather JL, Drover JW. The role of nutrition rehabilitation in the recovery of survivors of critical illness: underrecognized and underappreciated. Crit Care. 2022;26:270.

Turnbull AE, Rabiee A, Davis WE, Nasser MF, Venna VR, Lolitha R, Hopkins RO, Bienvenu OJ, Robinson KA, Needham DM. Outcome measurement in ICU survivorship research from 1970 to 2013: a scoping review of 425 publications. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1267–77.

Davies TW, van Gassel RJJ, van de Poll M, Gunst J, Casaer MP, Christopher KB, Preiser JC, Hill A, Gundogan K, Reintam-Blaser A, et al. Core outcome measures for clinical effectiveness trials of nutritional and metabolic interventions in critical illness: an international modified Delphi consensus study evaluation (CONCISE). Crit Care. 2022;26:240.

Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Friedman LA, Bingham CO 3rd, Turnbull AE. Core outcome measures for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors. An international modified Delphi consensus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1122–30.

Spies CD, Krampe H, Paul N, Denke C, Kiselev J, Piper SK, Kruppa J, Grunow JJ, Steinecke K, Gülmez T, et al. Instruments to measure outcomes of post-intensive care syndrome in outpatient care settings—results of an expert consensus and feasibility field test. J Intensive Care Soc. 2021;22:159–74.

Cano-Vindel A, Muñoz-Navarro R, Medrano LA, Ruiz-Rodríguez P, González-Blanch C, Gómez-Castillo MD, Capafons A, Chacón F, Santolaya F. A computerized version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 as an ultra-brief screening tool to detect emotional disorders in primary care. J Affect Disord. 2018;234:247–55.

Wu Y, Levis B, Sun Y, He C, Krishnan A, Neupane D, Bhandari PM, Negeri Z, Benedetti A, Thombs BD. Accuracy of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Depression subscale (HADS-D) to screen for major depression: systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2021;373:1231.

Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Symonds P. Diagnostic validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in cancer and palliative settings: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2010;126:335–48.

Inoue S, Hatakeyama J, Kondo Y, Hifumi T, Sakuramoto H, Kawasaki T, Taito S, Nakamura K, Unoki T, Kawai Y, et al. Post-intensive care syndrome: its pathophysiology, prevention, and future directions. Acute Med Surg. 2019;6:233–46.

Tanaka K, Katayama S, Okura K, Okamura M, Nawata K, Nakanishi N, Shinohara A. Skeletal muscle mass assessment in critically ill patients: method and application. Ann Cancer Res Therap. 2022;30:93–9.

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489–95.

Nakamura K, Nakano H, Naraba H, Mochizuki M, Takahashi Y, Sonoo T, Hashimoto H, Morimura N. High protein versus medium protein delivery under equal total energy delivery in critical care: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2021;40:796–803.

Nakano H, Naraba H, Hashimoto H, Mochizuki M, Takahashi Y, Sonoo T, Ogawa Y, Matsuishi Y, Shimojo N, Inoue Y, et al. Novel protocol combining physical and nutrition therapies, Intensive Goal-directed REhabilitation with Electrical muscle stimulation and Nutrition (IGREEN) care bundle. Crit Care. 2021;25:415.

Arai Y, Nakanishi N, Ono Y, Inoue S, Kotani J, Harada M, Oto J. Ultrasound assessment of muscle mass has potential to identify patients with low muscularity at intensive care unit admission: a retrospective study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021;45:177–83.

Nakanishi N, Tsutsumi R, Okayama Y, Takashima T, Ueno Y, Itagaki T, Tsutsumi Y, Sakaue H, Oto J. Monitoring of muscle mass in critically ill patients: comparison of ultrasound and two bioelectrical impedance analysis devices. J Intensive Care. 2019;7:61.

Montgomery C, Stelfox H, Norris C, Rolfson D, Meyer S, Zibdawi M, Bagshaw S. Association between preoperative frailty and outcomes among adults undergoing cardiac surgery: a prospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2021;9:E777–87.

Theou O, van der Valk AM, Godin J, Andrew MK, McElhaney JE, McNeil SA, Rockwood K. Exploring clinically meaningful changes for the frailty index in a longitudinal cohort of hospitalized older patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75:1928–34.

Carlew AR, Fatima H, Livingstone JR, Reese C, Lacritz L, Pendergrass C, Bailey KC, Presley C, Mokhtari B, Cullum CM. Cognitive assessment via telephone: a scoping review of instruments. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2020;35:1215–33.

Wilson RS, Bennett DA. Assessment of cognitive decline in old age with brief tests amenable to telephone administration. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:19–25.

Pendlebury ST, Welch SJ, Cuthbertson FC, Mariz J, Mehta Z, Rothwell PM. Telephone assessment of cognition after transient ischemic attack and stroke: Modified telephone interview of cognitive status and telephone Montreal Cognitive Assessment versus face-to-face Montreal Cognitive Assessment and neuropsychological battery. Stroke. 2013;44:227–9.

Newkirk LA, Kim JM, Thompson JM, Tinklenberg JR, Yesavage JA, Taylor JL. Validation of a 26-point telephone version of the Mini-Mental State Examination. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17:81–7.

Tomichek JE, Stollings JL, Pandharipande PP, Chandrasekhar R, Ely EW, Girard TD. Antipsychotic prescribing patterns during and after critical illness: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2016;20:378.

Turnbull AJ, Donaghy E, Salisbury L, Ramsay P, Rattray J, Walsh T, Lone N. Polypharmacy and emergency readmission to hospital after critical illness: a population-level cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:415–22.

Morandi A, Vasilevskis E, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Solberg LM, Neal EB, Koestner T, Torres RE, Thompson JL, Shintani AK, et al. Inappropriate medication prescriptions in elderly adults surviving an intensive care unit hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1128–34.

Wischmeyer PE, San-Millan I. Winning the war against ICU-acquired weakness: new innovations in nutrition and exercise physiology. Crit Care. 2015;19(Suppl 3):S6.

Stanojcic M, Finnerty CC, Jeschke MG. Anabolic and anticatabolic agents in critical care. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016;22:325–31.

MacTavish P, Quasim T, Purdie C, Ball M, Barker L, Connelly S, Devine H, Henderson P, Hogg LA, Kishore R, et al. Medication-related problems in intensive care unit survivors: learning from a multicenter program. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17:1326–9.

MacTavish P, Quasim T, Shaw M, Devine H, Daniel M, Kinsella J, Fenelon C, Kishore R, Iwashyna TJ, McPeake J. Impact of a pharmacist intervention at an intensive care rehabilitation clinic. BMJ Open Qual. 2019;8: e000580.

Aljuhani O. The role of critical care pharmacists beyond Intensive Care Units: a narrative review on medication management for ICU survivors. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2022;58: e21012.

Mohammad RA, Eze C, Marshall VD, Coe AB, Costa DK, Thompson A, Pitcher M, Haezebrouck E, McSparron JI. The impact of a clinical pharmacist in an interprofessional intensive care unit recovery clinic providing care to intensive care unit survivors. JACCP J Am College Clin Pharm. 2022;5:1027–38.

Lee SJ, Gharbi A, Shin JE, Jung ID, Park YM. Myostatin inhibitor YK11 as a preventative health supplement for bacterial sepsis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;543:1–7.

Jeschke MG, Finnerty CC, Suman OE, Kulp G, Mlcak RP, Herndon DN. The effect of oxandrolone on the endocrinologic, inflammatory, and hypermetabolic responses during the acute phase postburn. Ann Surg. 2007;246:351–60 (discussion 60-2).

Determination that Oxandrin (Oxandrolone) tablets, 2.5 milligrams and 10 milligrams, were withdrawn from sale for reasons of safety or effectiveness. https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2023-19796.

Salawu A, Green A, Crooks MG, Brixey N, Ross DH, Sivan M. A proposal for multidisciplinary tele-rehabilitation in the assessment and rehabilitation of COVID-19 survivors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4890.

Jeffs L, Saragosa M, Law MP, Kuluski K, Espin S, Merkley J. The role of caregivers in interfacility care transitions: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:1443–50.

Hunter EG, Dignan M, Shalash S. Evaluating allied health inpatient rehabilitation educational materials in terms of health literacy. J Allied Health. 2012;41:e33–7.

Poland F, Spalding N, Gregory S, McCulloch J, Sargen K, Vicary P. Developing patient education to enhance recovery after colorectal surgery through action research: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7: e013498.

McWilliams DJ, Atkinson D, Carter A, Foëx BA, Benington S, Conway DH. Feasibility and impact of a structured, exercise-based rehabilitation programme for intensive care survivors. Physiother Theory Pract. 2009;25:566–71.

Goetz LH, Schork NJ. Personalized medicine: motivation, challenges, and progress. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:952–63.

Butcher BW, Eaton TL, Montgomery-Yates AA, Sevin CM. Meeting the challenges of establishing intensive care unit follow-up clinics. Am J Crit Care. 2022;31:324–8.

Modrykamien AM. The ICU follow-up clinic: a new paradigm for intensivists. Respir Care. 2012;57:764–72.

Hwang R, Bruning J, Morris NR, Mandrusiak A, Russell T. Home-based telerehabilitation is not inferior to a centre-based program in patients with chronic heart failure: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2017;63:101–7.

Levy CE, Silverman E, Jia H, Geiss M, Omura D. Effects of physical therapy delivery via home video telerehabilitation on functional and health-related quality of life outcomes. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52:361–70.

Breen L, Phillips SM. Skeletal muscle protein metabolism in the elderly: interventions to counteract the “anabolic resistance” of ageing. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2011;8:68.

Compher C, Bingham AL, McCall M, Patel J, Rice TW, Braunschweig C, McKeever L. Guidelines for the provision of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46:12–41.

Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, Calder PC, Casaer M, Hiesmayr M, Mayer K, Montejo-Gonzalez JC, Pichard C, Preiser JC, et al. ESPEN practical and partially revised guideline: clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr. 2023;42:1671–89.

van Zanten ARH, De Waele E, Wischmeyer PE. Nutrition therapy and critical illness: practical guidance for the ICU, post-ICU, and long-term convalescence phases. Crit Care. 2019;23:368.

Ridley EJ, Parke RL, Davies AR, Bailey M, Hodgson C, Deane AM, McGuinness S, Cooper DJ. What happens to nutrition intake in the post-intensive care unit hospitalization period? An observational cohort study in critically ill adults. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2019;43:88–95.

Wittholz K, Fetterplace K, Clode M, George ES, MacIsaac CM, Judson R, Presneill JJ, Deane AM. Measuring nutrition-related outcomes in a cohort of multi-trauma patients following intensive care unit discharge. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2020;33:414–22.

Moisey LL, Pikul J, Keller H, Yeung CYE, Rahman A, Heyland DK, Mourtzakis M. Adequacy of protein and energy intake in critically ill adults following liberation from mechanical ventilation is dependent on route of nutrition delivery. Nutr Clin Pract. 2021;36:201–12.

Salisbury LG, Merriweather JL, Walsh TS. Rehabilitation after critical illness: could a ward-based generic rehabilitation assistant promote recovery? Nurs Crit Care. 2010;15:57–65.

Rousseau AF, Lucania S, Fadeur M, Verbrugge AM, Cavalier E, Colson C, Misset B. Adequacy of nutritional intakes during the year after critical illness: an observational study in a post-ICU follow-up clinic. Nutrients. 2022;14:3797.

Chapple LS, Weinel LM, Abdelhamid YA, Summers MJ, Nguyen T, Kar P, Lange K, Chapman MJ, Deane AM. Observed appetite and nutrient intake three months after ICU discharge. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:1215–20.

Merriweather JL, Salisbury LG, Walsh TS, Smith P. Nutritional care after critical illness: a qualitative study of patients’ experiences. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29:127–36.

Zuercher P, Moret CS, Dziewas R, Schefold JC. Dysphagia in the intensive care unit: epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical management. Crit Care. 2019;23:103.

Macht M, Wimbish T, Bodine C, Moss M. ICU-acquired swallowing disorders. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2396–405.

Fadeur M, Preiser JC, Verbrugge AM, Misset B, Rousseau AF. Oral nutrition during and after critical illness: SPICES for quality of care! Nutrients. 2020;12:3509.

Ginguay A, De Bandt JP, Cynober L. Indications and contraindications for infusing specific amino acids (leucine, glutamine, arginine, citrulline, and taurine) in critical illness. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2016;19:161–9.

Deutz NE, Matheson EM, Matarese LE, Luo M, Baggs GE, Nelson JL, Hegazi RA, Tappenden KA, Ziegler TR, Group NS. Readmission and mortality in malnourished, older, hospitalized adults treated with a specialized oral nutritional supplement: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Nutr. 2016;35:18–26.

Nakamura K, Kihata A, Naraba H, Kanda N, Takahashi Y, Sonoo T, Hashimoto H, Morimura N. β-Hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate, Arginine, and Glutamine complex on muscle volume loss in critically ill patients: a randomized control trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2019;44:205–12.

Mathew SR, Elia J, Penfil S, Slamon NB. Application of telemedicine technology to facilitate diagnosis of pediatric postintensive care syndrome. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26:1043–50.

Das A, Cina L, Mathew A, Aziz H, Aly H. Telemedicine, a tool for follow-up of infants discharged from the NICU? Experience from a pilot project. J Perinatol. 2020;40:875–80.

Watson L, Woods CW, Cutler A, DiPalazzo J, Craig AK. Telemedicine improves rate of successful first visit to NICU follow-up clinic. Hosp Pediatr. 2023;13:3–8.

Balakrishnan B, Hamrick L, Alam A, Thompson J. Effects of COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome intensive care unit survivor telemedicine clinic on patient readmission, pain perception, and self-assessed health scores: randomized, prospective, single-center, exploratory study. JMIR Form Res. 2023;7: e43759.

Howroyd F, Earle N, Weblin J, McWilliams D, Williams J, Storrie C, Brennan R, Gautam N, Snelson C, Veenith T. Virtual post-intensive-care rehabilitation for survivors of COVID-19: a service evaluation. Cureus. 2023;15: e38473.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NN was involved in the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. KL, JH, AK, MY, HS, and KM were involved in the drafting of the manuscript. KN took part in the review concept and supervised all aspects of this review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakanishi, N., Liu, K., Hatakeyama, J. et al. Post-intensive care syndrome follow-up system after hospital discharge: a narrative review. j intensive care 12, 2 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-023-00716-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-023-00716-w