Abstract

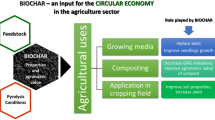

Recently, biochar has been widely used for versatile applications in agriculture and environment sectors as an effective tool to minimise waste and to increase the efficiency of circular economy. In the present work, we review the current knowledge about biochar role in N, P and K cycles. Ammonia volatilisation and N2O emission can be reduced by biochar addition. The content of available P can be improved by biochar through enhancement of solubilisation and reduction in P fixation on soil mineral, whilst high extractable K in biochar contributes to K cycle in soil. Liming effect and high CEC are important properties of biochars improving beneficial interactions with N, P and K soil cycle processes. The effectiveness of biochar on N, P and K cycles is associated with biochar properties which are mainly affected by feedstock type and pyrolysis condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biochar, a pyrogenic material derived from the thermochemical conversion of biomass in an oxygen-depleted environment, has come into the limelight in the last decade for its potential to foster soil C sequestration. In addition, biochar can be a multifunctional player for local circularity across agriculture, energy and environmental domains in several processes such as substitution of activated carbon [1], nutrient retention [2], enhancement of anaerobic conditions in biorefinery processes [3], immobilisation of heavy metals in mining soils [4] decontamination of water [5], and sorption of pesticides [6]. Generally, physical (e.g., large porosity and surface area) and chemical (e.g., recalcitrant aromatic C structure, hydrophobicity, cation exchange capacity) properties of biochar are the key factors bringing these multi-beneficial utilities [2, 7, 8].

A large number of review reports has been published regarding biochar from different and specific aspects such as key component for recovering of contaminated soil [9], soil conditioner [1, 10], application in upland fields and political support for biochar use [11]. However, there are only a few reports regarding biochar interaction with different soil nutrient cycles [12, 13] and its multiple-use in the agricultural domain. Nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium are the primary nutrients required by plants for growth, whereas several biochar interactions with soil components can contribute to increase the availability of these nutrients. Here, our review presents the role of biochar for different reactions in cycles of these three nutrients.

Biochar chemical characterisation

Biochar properties rely on the content and chemical nature of organic and inorganic components in its matrix. Carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, sulphur and nitrogen prevail in the biochar organic matter. Mineral elements, such as silica, aluminium, calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, sodium and potassium, are mainly present in biochar ash. The content of C in biochar increases in the range 17 to 85% with increasing pyrolysis temperature [14,15,16], whilst, on average, organic C accounts for less than 50% of total C [15]. In general, total C increases over pyrolysis temperature whilst biochar yield is decreased [17]. The functional groups found in biochar include hydroxyl, epoxy, carbonyl, carboxyl, ether, ester, sulphonic, aliphatic, phenolic and aromatic C groups [9, 18]. Especially, biochar enriched with carboxyl and phenolic C groups has a higher cation exchange capacity (CEC), thus presenting a higher capacity to adsorb nutrients [19].

The properties of biochar are significantly dependent on the feedstock types and the pyrolysis conditions, as well as on pre- and post-pyrolysis treatments [9, 18]. During the pyrolysis, lignocellulosic compounds in the feedstock are converted to aliphatic C groups at pyrolysis temperature around 400 °C. Furthermore, at temperatures above 500 °C, aromatisation and graphitisation processes occur [18], which increase the content of aromatic C groups and the degree of hydrophobicity, therefore enhancing nutrient absorption [8]. At the same time, other properties are reduced, such as the O/C and H/C ratios and the content of carboxyl groups, which are prone to interact with soil C pools [9, 20]. The CEC of biochar is also strongly associated with the type of feedstock and pyrolysis conditions [14, 21]. Woody-derived biochars have lower CEC than manure waste biochars, whilst high-temperature biochars have lower CEC than low-temperature biochars. Therefore, the selection of the proper pyrolysis conditions is a key step to formulate biochar for specific use and purposes in soil [9, 18].

Regarding optimal application rate in pot, Jaiswal et al. [22] concluded that an inverted U-shaped relationship between biochar dose and plant growth is a common pattern. However, under field conditions, most of the significant improvements in crop yield were obtained at high biochar application rates (> 2.5 tonnes ha−1) [23].

Nitrogen

Nitrogen (N) is an important element for ecosystems and biochar can be a useful tool contributing to N input in soil–plant system. As previously mentioned, there is a wide variety of feedstocks for biochar production. Usually, manure-based biochar presents high-nutrient contents than plant-based biochar. However, the average N available as nitrate in different types of biochar is generally less than 0.01% [24]. Despite the low content of available N, biochar plays an important role in determining N availability in soil as it may directly or indirectly influence various N forms and processes (Fig. 1) involved in the N cycle, such as dissolved organic N, N immobilisation and mineralisation, nitrification, N2O emission, ammonia volatilisation, and biological N2 fixation [25,26,27]. Generally, biochar has a large potential for decreasing soil N losses in different soil types, whilst the influence on crop production is lower in temperate regions than in tropical ones [28].

Dissolved organic N

In general, biochar application to soil decreases NO3− and NH4+ leaching, but does not reduce dissolved organic N (DON) leaching since most of the DON carries a net negative charge [26]. Also, DON turnover of organic matter pool in contrasting agricultural environments is not influenced by the application of fresh or aged biochar [29]. Jones et al. [30] found a small and transient impact of biochar addition to soil on DON turnover. Conversely, other authors report that biochar addition at high application rate reduces protein and free amino acid production and consumption which slows down soil organic N cycling [31].

Biochar impact on N immobilisation and mineralisation

Soil application of biochar produced at low pyrolysis temperature (< 350 °C) increases the rate of organic N mineralisation to NH4+, in comparison to biochar produced at 550 °C, due to a larger labile C fraction [27]. In addition, acid functional groups and labile C are present on the surface of biochar produced at low temperature and this type of biochar normally adsorbs more NH4+ in comparison with biochar produced at high temperature [32]. Probably, the labile C content of low-temperature biochar may contribute to immobilising N in the mineral soil [33]. The application of biochar accelerates soil N transformations in the short term with increased N bioavailability through N mineralisation of recalcitrant pools, followed by immobilisation of NH4+ in the labile soil organic N pool [22]. Furthermore, Nelissen et al. [27] reported that NH4+ is immobilised quickly by adsorption, which thereby consequently reduces available N and concomitantly minimises potential soil N losses. The application of slow pyrolysis biochar in the soil presents N immobilisation for a much shorter period than the fast pyrolysis biochar [34]. The same authors report that N immobilisation after biochar application in the soil is a transient phenomenon because the labile part is mineralised after a few months. Biochar application had a significant impact on both N mineralisation and immobilisation, but since there is a balance between gross N mineralisation and gross N immobilisation the soil net N mineralisation is not significantly altered by biochar application [35]. An increase in gross N immobilisation may be induced by microbial activity when large availability of C in the labile fraction of biochar increases [36].

Biochar impact on nitrification

Changes in water status and distribution in the soil, associated with changes in soil oxygenation, may increase nitrification rates in biochar amended soils since nitrification is dependent on soil O2 availability [31]. Abujabhah et al. [37] have shown that rising biochar application rates (0, 2.5 and 5% wt/wt) reduced NH4+ and increased NO3−. Underlying factors of this result were biochar sorption capacity and increased soil aeration which favoured higher nitrification rate. The enhanced nitrification rate with rising biochar application rates could have also been due to the increase in pH in these soils amended with biochar [27, 31] which may have stimulated autotrophic nitrification [36]. Despite the positive effect of nitrification on increasing plant-available N, a better understanding of the long-term effects of biochar amendment on soil N cycling in various agricultural settings is required for full exploitation of biochar potential [31]. In this context, it is known that the use of biochar reduces NO3− leaching and N2O emission in horticulture and arable farming, but it does not affect losses in perennial crops and grasslands [38].

Biochar as an electron shuttle and its influence on N2O emission

The function of biochar as an electron shuttle transferring electrons to denitrifying soil microorganisms, in combination with the liming effect and high surface area of biochar, has been reported as an explanation of the N2O emission rate reduction in biochar-amended soils [39].

The use of biochar may reduce N2O emissions by approximately 40% in Anthrosols and Arenosols. Beyond N2O emissions reduction, biochar application also reduces NO3− leaching, which increases the efficient use of N and ultimately mitigates climate change [38].

In biochar pyrolysed at low temperature, reduced phenolic moieties, acting as electron donors, enhanced N2O reduction, whilst in biochar pyrolysed at high temperature the oxidised quinone moieties, functioning as electron acceptors, decreased denitrification rate and N2O emissions [40]. Furthermore, the electrical conductivity structure of biochar produced at high-temperature promoted N2O reduction. The biochar function as an electron shuttle tends to decrease or even suppress soil N2O emission inversely to the biochar ageing [41]. However, the mechanisms involved in the modification of nitrification and denitrification genes caused by biochar application to soil are not fully elucidated [42]. The biotic and abiotic mechanisms responsible for inducing soil N2O mitigation by biochar are probably a result of soil and biochar properties and their interactions [43]. An example of these interactions is the inhibition of the nitrification process and the reduction of denitrifiers activity due to an increase in soil moisture and aeration of soil caused by biochar application [44, 45]. Concerning the suppression of N2O emission from denitrification, the ideal biochar properties are high carbonisation degree, high pH and large surface area [33]. Besides to reduce N2O emission, biochar must be applied in adequate proportion with N fertiliser to ensure a C/N ratio greater than 60 [46].

In addition to understanding the mechanisms involved in biochar influence on N2O emission, another critical factor for improving biochar management practices is the duration of their effect on N2O emission mitigation [47]. According to Borchard et al. [38], in general, the reduction of N2O emission due to biochar application tends to have a minor effect after 1 year. The benefits of biochar on soil greenhouse gas emissions are also highly influenced by soil conditions, especially the water content, which controls N-cycling pathways [48]. Considering the many types of biochars that affect the soil N2O emissions differently, further research into the use of these materials in crops under different field conditions is required [49]. In addition, there is a lack of experimental data regarding the effect of long term and repetitive additions of biochar to the soil [28].

Ammonia volatilisation

Ammonia (NH3) volatilisation, especially in tropical soils due to high temperature and low soil CEC, is the primary source of soil N loss and results in low N use efficiency by crops [28, 50]. According to Mandal et al. [50], the most common form of N fertiliser used in agriculture is urea, and the ammonification of urea raises the soil pH which consequently increases NH3 volatilisation rates.

Biochar application may contribute to decreasing NH3 emissions. The effectiveness of biochar in reducing NH3 volatilisation in soils where ammonia N fertiliser was applied depends on its surface area and the presence of acidic functional groups responsible for NH3 adsorption [51, 52]. Another factor that may contribute to the reduction of NH3 volatilisation is the retention of NH4+ due to increase of soil cation exchange capacity (CEC) after biochar application [51]. According to Sha et al. [53], the application of wood biochar at rates of 5 to 15 t ha−1, combined with N fertiliser rates lower than 200 kg N ha−1, may contribute to the reduction of NH3 volatilisation.

Conversely, it has also been shown that application of biochar with high pH (> 9) and application rates greater than 40 t ha−1 in clay acidic soils (pH ≤ 5) with low SOC (≤ 10 g kg−1) increases NH3 volatilisation [23]. Also, the combination of biochar and ammonium-based N fertilisers causes high NH3 volatilisation [53]. The increase of NH3 volatilisation in low pH soils occurs due to soil pH increase caused by biochar [35]. With increasing soil pH, there is an enhanced supply of OH− to NH4+ which is converted to NH3.

Relationship between biochar and N fixation

The N2 fixation is a crucial pathway to enhance soil N availability in various ecosystems, especially when the N supply is limited [54]. Biological N fixation (BNF) is an essential ecosystem service for agriculture and thereby understanding the relationship and impacts of biochar application on BNF is vital [55]. The application of biochar may increase the BNF in legumes, on average, by 63%, and this effect is mainly occurring in acidic soils (pH ≤ 5) [35]. Azeem et al. [56] showed that the application of 10 t ha−1 of biochar produced by pyrolysis of sugarcane bagasse biomass at 350 °C in mash bean plots increased nodule figures by 89% and N2 fixation by 83% in comparison to treatments without biochar, respectively. The biochar should be selected according to soil and plant type to promote BNF in root nodules or by association with free-living bacteria [57]. Eucalyptus biochar application at 60 g of biochar kg−1 of soil increased by 78% BNF of Phaseolus vulgaris L. compared to control due to higher availability of B and Mo [58]. However, the authors found that increasing the biochar rate to 90 g kg−1 decreased BFN and biomass production probably due to lower N availability and consequently lower photosynthate production. A small application rate (10 t ha−1) of biochar obtained from the aboveground plant biomass of pasture plants resulted in higher nodulation and BNF of Trifolium pratense L. due to the higher availability of K, whilst a very high application rate (120 t ha−1) led to a reduction in the amount of BNF and biomass production [55]. The application of 10 t ha−1 of paper mill biochar under acidic soil conditions caused a liming effect, which resulted in higher BNF, yield of Vicia faba L. and Mo absorption [59]. In a temperate pasture with intercropping of legumes and grasses, the ageing of the applied biochar tended to decrease the BNF and the competitiveness of the legumes with the grasses [60].

Anthropogenic activity in the soil negatively affects the soil microbial community and the greater the human interference with soil, the greater the potential for BNF after biochar application [54]. Furthermore, biochar application in soils with low organic C content not only increases BNF, but also enhances crop productivity by improving N content and decreasing bulk density [56]. Concomitantly biochar can increase soil N content not only directly, but also indirectly through the transportation of manure-derived biochar by insects [61].

Phosphorus

Phosphorus (P) is an essential macronutrient for plant growth; however, only 10 to 25% of P applied with mineral fertilisers is considered to be taken up by plants [62], whilst the rest is fixed in soils or is lost to water bodies. Soil properties; such as pH, compositions of mineral and organic matter, cation exchange capacity and texture, control plant availability of P in soils [63].

Application of biochar is known to influence, both directly and indirectly, soil P dynamics by adding extra P present in the biochar, changing soil pH and shifting microbial community compositions. The meta-analysis of 108 pairwise comparisons by Glaser and Lehr [64] and the data from 124 peer-reviewed papers resumed by Gao et al. [65] both showed that plant-available P in agricultural soils was significantly increased by the application of biochar produced from different materials and pyrolysis conditions, as well as for a variety of climate and soil types. The plant-available P in soils tends to increase with the biochar application rate [59], and an application rate above 10 Mg ha−1 is recommended for achieving positive effects on the plant-available P in soils [58].

The beneficial effects of biochar on nutrient cycles, however, are specific to biochar properties [63, 66,67,68]. The quantification of P present in biochar is source dependent; biochars produced from nutrient-rich feedstocks, such as manure and crop residues, generally have higher P values than those from lignocellulosic feedstocks, and therefore are best suited to be used as soil P fertiliser [52, 69]. For example, the study performed by Novak et al. [70] showed that the concentration of total P in manure-based biochars was 53 to 105 times higher than that in lignocellulosic-based biochars and the release of dissolved P in soils amended with manure-based biochars was approximately 850 times higher than in the soils amended with lignocellulosic-based biochars.

Transformation of P forms during the pyrolysis process

A large amount of inorganic P remains in the biochar, since organic P present in original materials is transformed into inorganic P during the pyrolysis process at temperatures above 350 °C [71]. Speciation of inorganic P in biochar is strongly dependent on the pyrolysis temperatures, where P complexation in ash compounds occurs during carbonisation [72, 73]. When produced at a temperature above 600 °C, orthophosphate becomes the dominant P species in biochar, whilst pyrophosphate is often the dominant species in biochar produced between 350 and 600 °C [71]. In the study carried out by Bruun et al. [74], labile calcium phosphates, such as brushite and magnesium phosphates, were the dominant P species in the biochar produced from digestate solids at low temperature, whilst these P compounds were transformed into more stable P minerals, such as apatite, in biochars produced above 600 °C. Therefore, the proportion of available P in biochar primarily depends on the pyrolysis temperature.

Change in the P fixation mechanism in soils by biochar amendment

Pyrolysis temperature also affects biochar’s alkalinity. Biochar, especially that derived from mineral-rich materials, is commonly alkaline, and alkalinity increases with increasing pyrolysis temperature [63, 75, 76]. For instance, the initial pH of ~ 3.2, 6.3, and 7.5 for oak wood, corn stover and poultry litter, respectively, became the final pH of ~ 7.9, 9.4 and 10.3 after pyrolysis at 600 °C, respectively [60].

Application of alkaline biochar increases soil pH and induces change to P dynamics in acidic soils, especially in soils with low P sorption capacity [63, 67]. Phosphorus tends to complex with Al or Fe to form Al- or Fe-P minerals in acidic soils and/or is strongly bound to Al- or Fe-(hydr)oxides, and thus become unavailable for plants. These Al- or Fe-P minerals will be solubilised when pH increases above 7 [77]. In the study by Schneider and Haderlein [72], significant P release by addition of biochar was observed in acidic soils rich in goethite (i.e. Fe-oxides). Introducing dissolved organic matter into soils is known to reduce soil P fixation through competing for sorption sites, forming chelates between cations, such as Fe3+ and Al3+, and organic molecules [78], and enhancing electrostatic repulsive forces [72]. Therefore, the P release observed in the study performed by Schneider and Hederlein [72] was most likely caused by the negatively charged organic matter derived from biochar, which reduced P sorption on goethite in addition to increase the soil pH.

Furthermore, Hiemstra et al. [79] studied the interaction of pyrogenic organic matter and oxide surfaces with P and estimated that the long-term addition of biochar could release P in acidic soils (i.e. pH < 5.5) by more than tenfold compared to P in soil without biochar amendment. The biochar-derived dissolved organic matter had a higher number of carboxylic groups than soil humic acid, thus actively interacted with metal (hydr)oxides resulting in reduced P sorption [79].

In the case of alkaline soils, biochar does not play a major role in P transformation. Phosphorus is strongly bound to Ca compounds in alkaline conditions above pH 7. Thus, soil P fixation increases in alkaline soils amended with biochar through precipitation of Ca-P minerals and P sorption onto calcite in alkaline soils due to additional input of alkaline elements such as Ca, which is often contained in biochar [63]. In general, biochar had no effect on P sorption isotherms in alkaline soils, especially in soils with high P sorption capacity [63, 80].

In contrast to the positive impact on soil-available P described previously, especially in acidic soils, it has been shown that biochar with low P content can reduce P availability in soils [72], through increasing P sorption capacity promoted by surface area increase [81] and in metal oxides and carbonates [82] derived from biochar, through immobilisation of P by stimulating microbial activity [80, 83] and by means of precipitation of stable phosphate minerals in alkaline soils [65].

Enhancement of P solubilisation and mineralisation by altering microbial community activity and structure

Change in soil pH caused by biochar also influences the phosphatase activity and the microbial abundance. The meta-analysis of the effects of biochar amendment on soil enzyme activities performed by Zhang et al. [84], where 401 paired comparisons were analysed amongst 43 peer-reviewed published papers, showed that overall soil enzyme activity linked to P cycling increased by 11%. The significant increase of the enzyme activity linked to P cycle was observed especially in acidic and neutral farmland soils, as well as with the addition of biochar produced at high temperatures [84]. Similarly, several other studies showed shifts in enzyme activities induced by biochar addition [65, 85]; for instance, alkaline phosphomonoesterase activities were increased, whilst acidic phosphomonoesterase activities were inhibited by addition of biochar regardless of soil types [86, 87]. However, this effect could have been partly due to the absorption of the substrate or enzymes, which occurs more strongly at lower pH rather than at a higher one [88, 89]. In fact, the study performed by Masto et al. [90] showed that both alkaline and acid phosphomonoesterase activities increased in red soils with addition of the biochar produced from Eichornia. They also observed a threefold increase in soil microbial biomass after application of biochar [90]. The enhancement of microbial biomass was also observed in other studies performed in a wide range of soil types [75, 91], where it is known that mineralisation of P also enhances with increasing microbial biomass [91].

Other studies showed a shift of microbial community composition towards a higher proportion of fungi over bacteria after the addition of biochar to the soil [83, 92], due to the increase in porosity caused by biochar that makes the habitat more favourable for fungi [93]. Fungi are known to be important decomposers in soils [75].Therefore, the increase in fungi abundance caused by biochar application also enhances the plant available P in soils through accelerated mineralisation of organic P [83].

Potassium

Speciation and transformation of K in biochar

Biochar typically contains a large amount of potassium (K), whose concentration usually ranges from 0.70 to 116 g kg−1 [24]. During pyrolysis, C and N become volatile at milder temperatures, whilst K begins to volatise at a relatively higher temperature over 700 °C [25]. Therefore, an increase in K concentration tends to occur in most of the manufactured biochar. Depending on the feedstock biomass and pyrolysis condition, the contents of extractable K in the biochar can be variable. Typically, water-soluble K increased as the pyrolysis temperature increased [94]. In other reports, extractable K initially increased with increasing pyrolysis temperature, but then declined when pyrolysis temperature became elevated [95]. Potassium-enriched biochar has been manufactured from K-rich biomass, such as animal manures [96], banana peduncle [97], rice straw [98] and seaweeds [7].

A number of observations was documented on the transformation and speciation of K in feedstocks during pyrolysis [99]. Zheng et al. [94] observed an increase of water-soluble K (from 37 to 47%) in giant reed biochar with increasing pyrolysis temperature from 300 to 600 °C, whilst most of the K in the feedstock was transformed into crystallised minerals during pyrolysis. Tan et al. [100] showed that stable and complexed K forms in rice straw were converted into soluble K forms such as potassium sulphate, potassium nitrate and potassium chloride during pyrolysis, which are more easily absorbed by plants. Biochar amendment, therefore, potentially serves as a direct source of K nutrient, which would be an especially suitable amendment for K-deficient soils [94]. However, presence of K nutrient in the biochar or biochar-applied soils does not guarantee that this will be available to plants. Liu et al. [99] suggested that water-insoluble portions of K are embedded in the carbon skeleton structure in highly ordered pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) intercalation compounds or in complex-K, which are stable in the soil and dissolves only slowly during ageing of biochar in the long term.

Impact of biochar on K availability in soils

Availability of biochar-derived K nutrient to plants will depend on several physicochemical factors such as solubility of K compounds into water and/or high ionic strength solution, the extent and rate of dissolution of these compounds from biochar to soils, and properties of the soils such as texture, exchange capacity, pH, and water content. Prakongkep et al. [101] reported that biochars produced from 14 tropical plant wastes contained 3.5–51 g kg−1 total K, in which water-soluble K content was in the range of 0.4–30 g kg−1. In an 8-week experiment, Limwikran et al. [102] examined the kinetics of mineral dissolution from nine biochars manufactured from tropical plant wastes into the tropical soils of Oxisols and Ultisol. They reported that some of the water-soluble K was rapidly diffused into the soil, whilst the remaining K fraction was slowly dissociating. Absorption of a considerable amount of Ca by biochar in exchange for the K release was shown in this experiment, suggesting a complex interaction amongst plant nutrients in the biochar–soil environment [102]. Novak et al. [70] examined the release kinetics of K and P from various biochar in fine-loamy soil in a 150-d column leaching experiment, which showed an initial rapid release of dissolved K, followed by a significant decline in the dissolved K content in the leachate from soils supplemented with either poultry litter biochar or ‘designer biochar’ at a blending ratio of 80:20 pine chip/poultry litter biochar. They also reported that such a blended biochar was aligned with soil P and K levels recommended for corn production in southeastern USA Coastal Plain sandy soils [70].

Effects of biochar as K fertilisers

Biochar can assist in improving K availability and K use efficiency in plants. A meta-analysis of 371 independent studies strongly suggested that biochar application resulted in increased soil K content and plant K tissue concentration [12]. In cotton, application to soil of 1% biochar together with chemical fertiliser significantly increased K content of different plant parts and improved growth and yield [103]. Amendment with biochar from K-rich crop residues, particularly those made from wheat straw, increased available K in sandy loam soil [104]. Application of poultry litter and hardwood biochar improved diary pasture yield in Australian Ferralsols, which was attributed to the alleviation of K and P nutrient constraints in the Ferralsol regardless of the N fertiliser dose applied [48].

In general, increased soil CEC gained by the application of biochar, due to its structural properties such as porous structure, large surface area and negative surface charge, tends to strengthen the retention of K and enable the slow release of nutrients [105]. Kizito et al. [106] examined the effect of soil application of corn cob and wood biochar saturated with an anaerobic digestate (AD) derived from biomethanol production. They observed that the application of AD-enriched wood biochar to clay loam soil at a rate of 20 t ha−1 increased soil CEC by > 300%, which were accompanied with a significant increase in the soil macronutrient contents including K, and aboveground biomass of cultivated maize plants.

The long-term effects of biochar-based K supplementation have been addressed in several studies. Two years of maize cultivation on Midwestern Mollisols, amended with hardwood biochar, significantly increased soil available K content and enhanced plant K uptake in the drought year; the latter effect was attributable to the increase in highly mobile K and was favoured by elevated moisture content in biochar-amended soils [107]. A 3-year field study in cotton–garlic intercropping system demonstrated that application of corn straw biochar at 5–20 t ha−1 at each cotton season increased the available K content of the 0–20 cm soil layer, and significantly improved cotton yield in the 3 successive years [108]. It is noteworthy that the biochar application also improved fiber qualities of harvested cotton such as fiber length and fiber strength, which is known to be adversely affected by K- and N-deficiency, but not by P-deficiency, suggesting that the observed amelioration of cotton fiber quality can be attributable to the supply of these nutrients [108]. These observations suggested that biochar application may offer an effective measure for sustainable agriculture in the long term.

Biochar as a liming input

In addition, increased concentration of K in biochar, together with Mg and Ca, functions as a liming agent to neutralise acid soils [109]. Meta-analysis of the literature showed that biochar application led to a reduction in the acidity of the soil in multiple studies [110]. The 90-day incubation experiments in acidic Ultisol supplemented with four crop residue biochar increased soil pH and exchangeable base cations and decreased exchangeable Al3+, especially for legume crop residue biochar [111]. As a matter of fact, the biochar amendment shows pronounced improvement of crop growth and yield in acidic soils [112].

Biochar and K leaching

Being a monovalent basic cation, K is highly susceptible to leaching [113]. Although biochar amendment can increase K leaching by supplying a significant amount of mobile K, at the same time biochar amendment can increase CEC, which strengthens the retention of K, thereby potentially functioning as a suppressor of leaching. A soil column experiment in which rice plants were grown showed a marked increase in K concentration in the leachate of a biochar-amended sandy soil, whilst no significant enhancement of K leaching was observed in biochar-amended clay soil [114], suggesting multiple interactions amongst soluble K, other nutrients, biochar, and soil types.

Conclusions

Biochar is involved with many soil N transformation processes (e.g. ammonia volatilization, N2O emission and biological nitrogen fixation), resulting in decreasing N losses and improving N retention. Biochar prevents P fixation in acidic soils and increases P solubilisation as a consequence of the enhanced microbial activity as well as changing pH in soils, thus increasing soil P availability. Content of extractable K in soil increases after biochar amendment, although original content of K in biochar is largely variable. The properties of biochar are significantly dependent on the feedstock types and the pyrolysis conditions, as well as on pre- and post-pyrolysis treatments, which also consistently affect the impact of biochar on soil cycles of N, P and K. Therefore, screening of biochars is highly recommended to avoid losses and increase the retention of N, P and K labile forms in soils. To use biochar effectively as a replacement of chemical fertiliser, knowledge of the composition and speciation of element in biochar and the characteristic of soils amended is essential. Given that most of the reports on increased yield in field applications are the result of a high biochar application rate, it is important to develop biochar fertilisers highly efficient even at low application dose based on nanostructures and soluble components [23]. Change in biochar properties due to the ageing effect is another topic deserving future research [21, 60, 115]. Also, some possibly negative impact of biochar amendment to soil should be taken into consideration such as potential increases in P leaching [63] and high EC [116]. Considering the above-mentioned matters, future studies should include the development of standard characteristics in biochar properties [75] and a better understanding of potential and long-term biochar-induced changes in the nutrient cycles under various environments, soil types, and land management.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CEC:

-

Cation exchange capacity

- N:

-

Nitrogen

- DON:

-

Dissolved organic nitrogen

- BNF:

-

Biological nitrogen fixation

- P:

-

Phosphorus

- K:

-

Potassium

- HOPG:

-

Highly ordered pyrolytic graphite

- AD:

-

Anaerobic digestate

- EC:

-

Electrical conductivity

References

Saletnik B, Zagula G, Bajcar M, Tarapatskyy M, Bobula G, Puchalski C. Biochar as a multifunctional component of the environment—a review. Appl Sci. 2019;9(6):1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9061139.

Kameyama K, Miyamoto T, Shiono T, Shinogi Y. Influence of sugarcane bagasse-derived biochar application on nitrate leaching in calcaric dark red soil. J Environ Qual. 2012;41(4):1131–7. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2010.0453.

Pan J, Ma J, Zhai L, Luo T, Mei Z, Liu H. Achievements of biochar application for enhanced anaerobic digestion: a review. Bioresour Technol. 2019;292:122058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122058.

Penido ES, Martins GC, Mendes TBM, Melo LCA, Rosário Guimarães I, Guilherme LR. Combining biochar and sewage sludge for immobilization of heavy metals in mining soils. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;172:326–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.01.110.

Dadwal A, Mishra V. Review on biosorption of arsenic from contaminated water. Clean Soil Air Water. 2017;45(7):1600364. https://doi.org/10.1002/clen.201600364.

Ćwieląg-Piasecka I, Medyńska-Juraszek A, Jerzykiewicz M, Dębicka M, Bekier J, Jamroz E. Humic acid and biochar as specific sorbents of pesticides. J Soils Sediments. 2018;18(8):2692–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-018-1976-5.

Eibisch N, Durner W, Bechtold M, Fuß R, Mikutta R, Woche SK. Does water repellency of pyrochars and hydrochars counter their positive effects on soil hydraulic properties? Geoderma. 2015;245–246:31–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2015.01.009.

Zornoza R, Moreno-Barriga F, Acosta JA, Muñoz MA, Faz A. Stability, nutrient availability and hydrophobicity of biochars derived from manure, crop residues, and municipal solid waste for their use as soil amendments. Chemosphere. 2016;144:122–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.08.046.

Yuan P, Wang J, Pan Y, Shen B, Wu C. Review of biochar for the management of contaminated soil: preparation, application and prospect. Sci Total Environ. 2019;659:473–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.400.

Sohi SP, Krull E, Lopez-Capel E, Bol R. A review of biochar and its use and function in soil. Adv Agron. 2010;105(1):47–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2113(10)05002-9.

Pourhashem G, Hung SY, Medlock KB, Masiello CA. Policy support for biochar: review and recommendations. GCB Bioenergy. 2019;11(2):364–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.12582.

Biederman LA, Stanley HW. Biochar and its effects on plant productivity and nutrient cycling: a meta-analysis. GCB Bioenergy. 2013;5(2):202–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.12037.

Horel Á, Gelybó G, Potyó I, Pokovai K, Bakacsi Z. Soil nutrient dynamics and nitrogen fixation rate changes over plant growth in temperate soil. Agronomy. 2019;9(4):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9040179.

Domingues RR, Trugilho PF, Silva CA, De Melo ICNA, Melo LCA, Magriotis ZM. Properties of biochar derived from wood and high-nutrient biomasses with the aim of agronomic and environmental benefits. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176884.

González ME, González A, Toro CA, Cea M, Sepúlveda N, Diez MC. Biochar as a renewable matrix for the development of encapsulated and immobilized novel added-value bioproducts. J Biobased Mater Bioenergy. 2012;6(3):237–48. https://doi.org/10.1166/jbmb.2012.1224.

Solaiman ZM, Abbott LK, Murphy DV. Biochar phosphorus concentration dictates mycorrhizal colonisation, plant growth and soil phosphorus cycling. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41671-7.

El-Naggar A, Lee SS, Rinklebe J, Farooq M, Song H, Sarmah AK. Biochar application to low fertility soils: a review of current status, and future prospects. Geoderma. May 2018;2019(337):536–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.09.034.

Xiao X, Chen B, Chen Z, Zhu L, Schnoor JL. Insight into multiple and multilevel structures of biochars and their potential environmental applications: a critical review. Environ Sci Technol. 2018;52(9):5027–47. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b06487.

Mekuria W, Noble A. The role of biochar in ameliorating disturbed soils and sequestering soil carbon in tropical agricultural production systems International Water Management Institute (IWMI), 127 Sunil Mawatha. Pelawatte: Appl Environ Soil Sci; 2013. p. 2013.

Crombie K, Mašek O, Sohi SP, Brownsort P, Cross A. The effect of pyrolysis conditions on biochar stability as determined by three methods. GCB Bioenergy. 2013;5(2):122–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.12030.

Mia S, Dijkstra FA, Singh B. Long-term aging of biochar: a molecular understanding with agricultural and environmental implications. Advances in agronomy, vol. 141. 1st ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017. p. 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.agron.2016.10.001.

Jaiswal AK, Frenkel O, Elad Y, Lew B, Graber ER. Non-monotonic influence of biochar dose on bean seedling growth and susceptibility to Rhizoctonia solani: the “Shifted Rmax-Effect”. Plant Soil. 2015;395(1–2):125–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-014-2331-2.

Joseph S, Graber ER, Chia C, Munroe P, Donne S, Thomas T, Nielsen S, Marjo C, Rutlidge H, Pan GX, Li L, Taylor P, Rawal A, Hook J. Shifting paradigms: development of high-efficiency biochar fertilizers based on nano-structures and soluble components. Carbon Manag. 2013;4(3):323–43. https://doi.org/10.4155/cmt.13.23

Ippolito JA, Spokas KA, Novak JM, Lentz RD, Cantrell KB. Biochar elemental composition and factors influencing nutrient retention. Biochar Environ Manag Sci Technol. 2014;137–62.

DeLuca TH, MacKenzie MD, Gundale MJ. Biochar effects on soil nutrient transformations. Biochar Environ Manag Sci Technol. 2012;10:251–70.

Dempster DN, Jones DL, Murphy DV. Clay and biochar amendments decreased inorganic but not dissolved organic nitrogen leaching in soil. Soil Res. 2012;50(3):216–21. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR11316.

Nelissen V, Rütting T, Huygens D, Staelens J, Ruysschaert G, Boeckx P. Maize biochars accelerate short-term soil nitrogen dynamics in a loamy sand soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 2012;55:20–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.05.019.

Liu Q, Liu B, Zhang Y, Hu T, Lin Z, Liu G. Biochar application as a tool to decrease soil nitrogen losses (NH3 volatilization, N2O emissions, and N leaching) from croplands: options and mitigation strength in a global perspective. Glob Chang Biol. 2019;25(6):2077–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14613.

Dempster DN, Jones DL, Murphy DV. Organic nitrogen mineralisation in two contrasting agro-ecosystems is unchanged by biochar addition. Soil Biol Biochem. 2012;48:47–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.01.013.

Jones DL, Rousk J, Edwards-Jones G, DeLuca TH, Murphy DV. Biochar-mediated changes in soil quality and plant growth in a three year field trial. Soil Biol Biochem. 2012;45:113–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.10.012.

Prommer J, Wanek W, Hofhansl F, Trojan D, Offre P, Urich T. Biochar decelerates soil organic nitrogen cycling but stimulates soil nitrification in a temperate arable field trial. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e86388. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086388.

Nguyen TTN, Xu CY, Tahmasbian I, Che R, Xu Z, Zhou X. Effects of biochar on soil available inorganic nitrogen: a review and meta-analysis. Geoderma. 2017;288:79–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.11.004.

Weldon S, Rasse DP, Budai A, Tomic O, Dörsch P. The effect of a biochar temperature series on denitrification: which biochar properties matter? Soil Biol Biochem. 2019;135:173–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2019.04.018.

Bruun EW, Ambus P, Egsgaard H, Hauggaard-Nielsen H. Effects of slow and fast pyrolysis biochar on soil C and N turnover dynamics. Soil Biol Biochem. 2012;46:73–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.11.019.

Liu Q, Zhang Y, Liu B, Amonette JE, Lin Z, Liu G. How does biochar influence soil N cycle? A meta-analysis. Plant Soil. 2018;426(1–2):211–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-018-3619-4.

Nelissen V, Rütting T, Huygens D, Ruysschaert G, Boeckx P. Temporal evolution of biochar’s impact on soil nitrogen processes—a 15N tracing study. GCB Bioenergy. 2015;7(4):635–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcbb.12156.

Abujabhah IS, Doyle R, Bound SA, Bowman JP. The effect of biochar loading rates on soil fertility, soil biomass, potential nitrification, and soil community metabolic profiles in three different soils. J Soils Sediments. 2016;16(9):2211–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-016-1411-8.

Borchard N, Schirrmann M, Cayuela ML, Kammann C, Wrage-Mönnig N, Estavillo JM. Biochar, soil and land-use interactions that reduce nitrate leaching and N2O emissions: a meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2019;651:2354–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.060.

Cayuela ML, Sánchez-Monedero MA, Roig A, Hanley K, Enders A, Lehmann J. Biochar and denitrification in soils: when, how much and why does biochar reduce N2O emissions? Sci Rep. 2013;3:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01732.

Chen G, Zhang Z, Zhang Z, Zhang R. Redox-active reactions in denitrification provided by biochars pyrolyzed at different temperatures. Sci Total Environ. 2018;615:1547–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.125.

Yuan H, Zhang Z, Li M, Clough T, Wrage-Mönnig N, Qin S. Biochar’s role as an electron shuttle for mediating soil N2O emissions. Soil Biol Biochem. 2019;133:94–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2019.03.002.

Van Zwieten L, Singh BP, Kimber SWL, Murphy DV, Macdonald LM, Rust J. An incubation study investigating the mechanisms that impact N2O flux from soil following biochar application. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2014;191:53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2014.02.030.

Van Zwieten L, Kammen C, Cayuela ML, Singh BP, Joseph S, Kimber S. Biochar effects on nitrous oxide and methane emissions from soil. Biochar Environ Manag Sci Technol Implement. 2015. https://books.google.com/books?id=gWDABgAAQBAJ&pgis=1

Shaukat M, Samoy-Pascual K, Maas ED, Ahmad A. Simultaneous effects of biochar and nitrogen fertilization on nitrous oxide and methane emissions from paddy rice. J Environ Manag. 2019;248:109242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.07.013.

Zhang A, Cui L, Pan G, Li L, Hussain Q, Zhang X. Effect of biochar amendment on yield and methane and nitrous oxide emissions from a rice paddy from Tai Lake plain, China. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2010;139(4):469–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2010.09.003.

Feng Z, Zhu L. Impact of biochar on soil N2O emissions under different biochar–carbon/fertilizer–nitrogen ratios at a constant moisture condition on a silt loam soil. Sci Total Environ. 2017;584–585:776–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.115.

Cayuela ML, van Zwieten L, Singh BP, Jeffery S, Roig A, Sánchez-Monedero MA. Biochar’s role in mitigating soil nitrous oxide emissions: a review and meta-analysis. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2014;191:5–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.10.009.

Van Zwieten L, Kimber S, Morris S, Macdonald LM, Rust J, Petty S. Biochar improves diary pasture yields by alleviating P and K constraints with no influence on soil respiration or N2O emissions. Biochar. 2019;1(1):115–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-019-00005-6.

Song Y, Li Y, Cai Y, Fu S, Luo Y, Wang H. Biochar decreases soil N2O emissions in Moso bamboo plantations through decreasing labile N concentrations, N-cycling enzyme activities and nitrification/denitrification rates. Geoderma. 2019;348:135–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.04.025.

Mandal S, Thangarajan R, Bolan NS, Sarkar B, Khan N, Ok YS. Biochar-induced concomitant decrease in ammonia volatilization and increase in nitrogen use efficiency by wheat. Chemosphere. 2016;142:120–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.04.086.

Clough TJ, Condron LM. Biochar and the nitrogen cycle: introduction. J Environ Qual. 2010;39(4):1218–23. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2010.0204.

Gul S, Whalen JK. Biochemical cycling of nitrogen and phosphorus in biochar-amended soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 2016;103:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.08.001.

Sha Z, Li Q, Lv T, Misselbrook T, Liu X. Response of ammonia volatilization to biochar addition: a meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2019;655:1387–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.316.

Horel A, Potyó I, Szili-Kovács T, Molnár S. Potential nitrogen fixation changes under different land uses as influenced by seasons and biochar amendments. Arab J Geosci. 2018;11(559):1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-018-3916-5.

Mia S, van Groenigen JW, van de Voorde TFJ, Oram NJ, Bezemer TM, Mommer L. Biochar application rate affects biological nitrogen fixation in red clover conditional on potassium availability. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2014;191:83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2014.03.011.

Azeem M, Hayat R, Hussain Q, Ahmed M, Pan G, Ibrahim TM. Biochar improves soil quality and N2-fixation and reduces net ecosystem CO2 exchange in a dryland legume–cereal cropping system. Soil Tillage Res. 2019;186:172–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2018.10.007.

Schmalenberger A, Fox A. Bacterial mobilization of nutrients from biochar-amended soils. Advances in applied microbiology, vol. 94. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2016. p. 109–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aambs.2015.10.001.

Rondon MA, Lehmann J, Ramírez J, Hurtado M. Biological nitrogen fixation by common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L) increases with bio-char additions. Biol Fertil Soils. 2007;43(6):699–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-006-0152-z.

Van Zwieten L, Rose T, Herridge D, Kimber S, Rust J, Cowie A. Enhanced biological N2 fixation and yield of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) in an acid soil following biochar addition: dissection of causal mechanisms. Plant Soil. 2015;395(1–2):7–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-015-2427-3.

Mia S, Dijkstra FA, Singh B. Enhanced biological nitrogen fixation and competitive advantage of legumes in mixed pastures diminish with biochar aging. Plant Soil. 2018;424(1–2):639–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-018-3562-4.

Joseph S, Pow D, Dawson K, Mitchell DRG, Rawal A, Hook J. Feeding biochar to cows: an innovative solution for improving soil fertility and farm productivity. Pedosphere. 2015;25(5):666–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0160(15)30047-3.

Syers JK, Johnston AE, Curtin D. Efficiency of soil and fertilizer phosphorus use: reconciling changing concepts of soil phosphorus behaviour with agronomic information. FAO Fertil Plant Nutr Bull. 2008;18:128.

Bornø ML, Müller-Stöver DS, Liu F. Contrasting effects of biochar on phosphorus dynamics and bioavailability in different soil types. Sci Total Environ. 2018;627:963–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.283.

Glaser B, Lehr VI. Biochar effects on phosphorus availability in agricultural soils: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45693-z.

Gao S, DeLuca TH, Cleveland CC. Biochar additions alter phosphorus and nitrogen availability in agricultural ecosystems: a meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2019;654:463–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.124.

Kavitha B, Reddy PVL, Kim B, Lee SS, Pandey SK, Kim KH. Benefits and limitations of biochar amendment in agricultural soils: a review. J Environ Manage. 2018;227:146–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.08.082.

Xu G, Sun JN, Shao HB, Chang SX. Biochar had effects on phosphorus sorption and desorption in three soils with differing acidity. Ecol Eng. 2014;62:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.10.027.

Zhang H, Chen C, Gray EM, Boyd SE, Yang H, Zhang D. Roles of biochar in improving phosphorus availability in soils: a phosphate adsorbent and a source of available phosphorus. Geoderma. 2016;276:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.04.020.

Chan KYA, Van Zwieten L, Meszaros IA, Downie AC, Joseph SD. Using poultry litter biochars as soil amendments. Aust J ofSoil Res. 2003;2008(46):437–44. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR08036.

Novak JM, Johnson MG, Spokas KA. Concentration and release of phosphorus and potassium from lignocellulosic- and manure-based biochars for fertilizer reuse. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2018;2:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2018.00054.

Uchimiya M, Hiradate S, Antal MJ. Dissolved phosphorus speciation of flash carbonization, slow pyrolysis, and fast pyrolysis biochars. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2015;3(7):1642–9. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b00336.

Schneider F, Haderlein SB. Potential effects of biochar on the availability of phosphorus—mechanistic insights. Geoderma. 2016;277:83–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2016.05.007.

Zhang H, Voroney RP, Price GW. Effects of temperature and activation on biochar chemical properties and their impact on ammonium, nitrate, and phosphate sorption. J Environ Qual. 2017;46(4):889–96. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2017.02.0043.

Bruun S, Harmer SL, Bekiaris G, Christel W, Zuin L, Hu Y. The effect of different pyrolysis temperatures on the speciation and availability in soil of P in biochar produced from the solid fraction of manure. Chemosphere. 2017;169:377–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.11.058.

Lehmann J, Rillig MC, Thies J, Masiello CA, Hockaday WC, Crowley D. Biochar effects on soil biota - A review. Soil Biol Biochem. 2011;43(9):1812–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.04.022.

Yuan JH, Xu RK, Zhang H. The forms of alkalis in the biochar produced from crop residues at different temperatures. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102(3):3488–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2010.11.018.

Sharpley A, Moyer B. Phosphorus forms in manure and compost and their release during simulated rainfall. J Environ Qual. 2000;29(5):1462–9. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2000.00472425002900050012x.

Zhou C, Heal K, Tigabu M, Xia L, Hu H, Yin D. Biochar addition to forest plantation soil enhances phosphorus availability and soil bacterial community diversity. For Ecol Manag. 2020;455:117635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.117635.

Hiemstra T, Mia S, Duhaut PB, Molleman B. Natural and pyrogenic humic acids at goethite and natural oxide surfaces interacting with phosphate. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(16):9182–9. https://doi.org/10.1021/es400997n.

Xu G, Shao H, Zhang Y, Junna S. Nonadditive effects of biochar amendments on soil phosphorus fractions in two contrasting soils. Land Degrad Dev. 2018;29(8):2720–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3029.

Trazzi PA, Leahy JJ, Hayes MHB, Kwapinski W. Adsorption and desorption of phosphate on biochars. J Environ Chem Eng. 2016;4(1):37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2015.11.005.

Ngatia LW, Hsieh YP, Nemours D, Fu R, Taylor RW. Potential phosphorus eutrophication mitigation strategy: Biochar carbon composition, thermal stability and pH influence phosphorus sorption. Chemosphere. 2017;180:201–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.04.012.

Mitchell PJ, Simpson AJ, Soong R, Schurman JS, Thomas SC, Simpson MJ. Biochar amendment and phosphorus fertilization altered forest soil microbial community and native soil organic matter molecular composition. Biogeochemistry. 2016;130(3):227–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-016-0254-0.

Zhang L, Xiang Y, Jing Y, Zhang R. Biochar amendment effects on the activities of soil carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus hydrolytic enzymes: a meta-analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26:22990–3001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05604-1.

Gao S, Hoffman-Krull K, DeLuca TH. Soil biochemical properties and crop productivity following application of locally produced biochar at organic farms on Waldron Island. WA Biogeochem. 2017;136(1):31–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-017-0379-9.

Jin Y, Liang X, He M, Liu Y, Tian G, Shi J. Manure biochar influence upon soil properties, phosphorus distribution and phosphatase activities: a microcosm incubation study. Chemosphere. 2016;142:128–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.07.015.

Nèble S, Calvert V, Petit Le J, Criquet S. Dynamics of phosphatase activities in a cork oak litter (Quercus suber L.) following sewage sludge application. Soil Biol Biochem. 2007;39(11):2735–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.05.015.

Foster EJ, Fogle EJ, Cotrufo MF. Sorption to biochar impacts β-glucosidase and phosphatase enzyme activities. Agric. 2018;8(10):1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture8100158.

Jindo K, Matsumoto K, García Izquierdo C, Sonoki T, Sanchez-Monedero MA. Methodological interference of biochar in the determination of extracellular enzyme activities in composting samples. Solid Earth. 2014;5(2):713–9.https://doi.org/10.5194/se-5-713-2014. https://doi.org/10.5194/se-5-713-2014.

Masto RE, Kumar S, Rout TK, Sarkar P, George J, Ram LC. Biochar from water hyacinth (Eichornia crassipes) and its impact on soil biological activity. Catena. 2013;111:64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2013.06.025.

Gul S, Whalen JK, Thomas BW, Sachdeva V, Deng H. Physico-chemical properties and microbial responses in biochar-amended soils: mechanisms and future directions. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2015;206:46–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2015.03.015.

Ameloot N, De Neve S, Jegajeevagan K, Yildiz G, Buchan D, Funkuin YN. Short-term CO2 and N2O emissions and microbial properties of biochar amended sandy loam soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 2013;57:401–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.10.025.

Blackwell P, Krull E, Butler G, Herbert A, Solaiman Z. Effect of banded biochar on dryland wheat production. Aust J Soil Res. 2010;48:531–45. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR10014.

Zheng H, Wang Z, Deng X, Zhao J, Luo Y, Novak J. Characteristics and nutrient values of biochars produced from giant reed at different temperatures. Bioresour Technol. 2013;130:463–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.12.044.

Wu W, Yang M, Feng Q, McGrouther K, Wang H, Lu H. Chemical characterization of rice straw-derived biochar for soil amendment. Biomass Bioenergy. 2012;47:268–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.09.034.

Subedi R, Taupe N, Pelissetti S, Petruzzelli L, Bertora C, Leahy JJ. Greenhouse gas emissions and soil properties following amendment with manure-derived biochars: influence of pyrolysis temperature and feedstock type. J Environ Manag. 2016;166:73–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.10.007.

Karim AA, Kumar M, Mohapatra S, Singh SK. Nutrient rich biomass and effluent sludge wastes co-utilization for production of biochar fertilizer through different thermal treatments. J Clean Prod. 2019;228:570–9.

Peng X, Ye LL, Wang CH, Zhou H, Sun B. Temperature- and duration-dependent rice straw-derived biochar: characteristics and its effects on soil properties of an Ultisol in southern China. Soil Tillage Res. 2011;112(2):159–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2011.01.002.

Liu L, Tan Z, Gong H, Huang Q. Migration and Transformation mechanisms of nutrient elements (N, P, K) within biochar in straw–biochar–soil–plant systems: a review. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2019;7(1):22–32.

Tan Z, Liu L, Zhang L, Huang Q. Mechanistic study of the influence of pyrolysis conditions on potassium speciation in biochar “preparation-application” process. Sci Total Environ. 2017;599–600:207–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.235.

Prakongkep N, Gilkes RJ, Wiriyakitnateekul W. Forms and solubility of plant nutrient elements in tropical plant waste biochars. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci. 2015;178(5):732–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.201500001.

Limwikran T, Kheoruenromne I, Suddhiprakarn A, Prakongkep N, Gilkes RJ. Dissolution of K, Ca, and P from biochar grains in tropical soils. Geoderma. 2018;312:139–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.10.022.

Wu X, Wang D, Riaz M, Zhang L, Jiang C. Investigating the effect of biochar on the potential of increasing cotton yield, potassium efficiency and soil environment. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;182:109451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109451.

Purakayastha TJ, Kumari S, Pathak H. Characterisation, stability, and microbial effects of four biochars produced from crop residues. Geoderma. 2015;239–240:293–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.11.009.

Zhou L, Cai D, He L, Zhong N, Yu M, Zhang X. Fabrication of a high-performance fertilizer to control the loss of water and nutrient using micro/nano networks. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2015;3(4):645–53. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b00072.

Kizito S, Luo H, Lu J, Bah H, Dong R, Wu S. Role of nutrient-enriched biochar as a soil amendment during maize growth: exploring practical alternatives to recycle agricultural residuals and to reduce chemical fertilizer demand. Sustain. 2019;11(11):1-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113211.

Rogovska N, Laird DA, Rathke SJ, Karlen DL. Biochar impact on Midwestern Mollisols and maize nutrient availability. Geoderma. 2014;230–231:340–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.04.009.

Tian X, Li C, Zhang M, Wan Y, Xie Z, Chen B. Biochar derived from corn straw affected availability and distribution of soil nutrients and cotton yield. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189924.

Gezahegn S, Sain M, Thomas S. Variation in feedstock wood chemistry strongly influences biochar liming potential. Soil Syst. 2019;3(2):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems3020026

Baidoo IK, Sarpong DB, Bolwig S, Ninson D. Biochar amended soils and crop productivity: a critical and meta-analysis of literature. Int J Dev Sustain. 2016;5(9):414–32.

Yuan JH, Xu RK, Qian W, Wang RH. Comparison of the ameliorating effects on an acidic ultisol between four crop straws and their biochars. J Soils Sediments. 2011;11(5):741–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-011-0365-0.

Liu X, Zhang A, Ji C, Joseph S, Bian R, Li L. Biochar’s effect on crop productivity and the dependence on experimental conditions—a meta-analysis of literature data. Plant Soil. 2013;373(1–2):583–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-013-1806-x.

Alfaro MA, Alfaro MA, Jarvis SC, Gregory PJ. Factors affecting potassium leaching in different soils. Soil Use Manag. 2004;20(2):182–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-2743.2004.tb00355.x.

Nguyen BT, Phan BT, Nguyen TX, Nguyen VN, Tran Van T, Bach QV. Contrastive nutrient leaching from two differently textured paddy soils as influenced by biochar addition. J Soils Sediments. 2019;20(1):297–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-019-02366-8.

Slavich PG, Sinclair K, Morris SG, Kimber SWL, Downie A, Van Zwieten L. Contrasting effects of manure and green waste biochars on the properties of an acidic ferralsol and productivity of a subtropical pasture. Plant Soil. 2013;366(1–2):213–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1412-3.

Macdonald LM, Farrell M, Van ZL, Krull ES. Plant growth responses to biochar addition: an Australian soils perspective. Biol Fertil Soils. 2014;50(7):1035–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-014-0921-z.

Acknowledgements

Keiji Jindo wish to acknowledge financial support (3710473400-1). Fábio Satoshi Higashikawa and Carlos Alberto Silva thank the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for financial support (403912/2016-4) and scholarship provided (303899/2015-8 Grant). Kinya Akashi would like to thank the Joint Research Program and the Project Marginal Region Agriculture of the Arid Land Research Center, Tottori University, and the IPDRE Program, Tottori University for financial supports. Miguel A. Sánchez-Monedero wish to thank the support by the Project No RTI2018-099417-B-I00 from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, cofunded with FEDER funds.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KJ, YA, FSH, CAS and KA wrote the manuscript; GM, MASM and CM collaborated to the text redaction and formatted the whole text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jindo, K., Audette, Y., Higashikawa, F.S. et al. Role of biochar in promoting circular economy in the agriculture sector. Part 1: A review of the biochar roles in soil N, P and K cycles. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 7, 15 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-020-00182-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40538-020-00182-8