Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of the maxillary posterior dentoalveolar discrepancy (MPDD) on the angulation of maxillary molars in open bite subjects.

Methods

Pre-treatment lateral cephalograms of 90 young adults with skeletal open bite were examined. The sample initially included six groups categorized according to MPDD condition (present or absent) and sagittal skeletal facial growth patterns (classes I, II, or III). Then, the sample was separated into two groups according to MPDD (present = 50, absent = 40). When the eruption of the maxillary third molar was apparently blocked by the presence of an erupted second molar, a MPDD was considered. Maxillary molar angulation was measured. Independent T test was performed to determine differences between the groups considering MPDD condition. Principal component analysis (PCA) and multivariate analysis (MANCOVA) test were also developed.

Results

A decreased molar angulation was found in all groups with MPDD (overall p < 0.001, class I—p < 0.001, class II—p < 0.001, and class III—p < 0.05). The maxillary first and second molars angulations were lower between approximately 7° and 14° in cases with posterior discrepancy. The PCA was used to reduce the number of initial cephalometric variables; thereafter, a MANCOVA test was applied. Significance was only found for MPDD (p < 0.001), APDI (p = 0.001), and ratio (A′6′/A′P′) (p = 0.026) for maxillary first molar angulation and APDI (p = 0.011) and MPDD (p < 0.001) for maxillary second molar angulation.

Conclusions

The MPDD generates a major mesial displacement of the second and first molar roots with a concurrent simultaneous distal angulation of the associated crowns in individuals with skeletal open bite.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The angulation of posterior molars has been studied in several papers [1–4] including individuals with different sagittal malocclusions associated with different sagittal and vertical growth patterns, but none so far has evaluated the specific impact of maxillary posterior dentoalveolar discrepancies (MPDD) (apparent lack of space for erupting third molars by inadequate pathway eruption) on molar angulations. It has been suggested that posterior discrepancies may be related to crowding relapse and third molar impaction [5–10]. Nevertheless, the majority of orthodontists and oral surgeons do not consider the preventive third molar extraction in order to prevent anterior crowding [11]. There are a few systematic reviews [12–14] in literature unsupportive on the role of the third molars in the development of late incisal crowding. In addition, it has been shown that a maxillary posterior discrepancy is not necessarily associated with increases in maxillary molar vertical eruption, overbite, or anterior lower facial height [15]. One hypothesis suggests that the posterior discrepancy should have an increase in the mesial angulation of the upper first and second molars (involving their crowns and roots) [6–10], while another hypothesis suggests that in MPDD cases, the pressure from the erupting maxillary third molar generates a mesial push over the second molar roots with a concurrent simultaneous distal tipping of their crowns [1].

Because of the existing controversy for either one of the described hypothesis, namely mesialization of posterior molars or a distoangulation of the molar crown with a concomitant mesialization of their roots, the purpose of this study was to determine the effect of the MPDD on the sagittal inclination of maxillary molars in open bite individuals with different sagittal malocclusions. If such associations existed, then this information could be useful for clinicians when treatment planning biomechanical approaches to cases with potential MPDD, especially in subject with skeletal open bite.

Methods

This retrospective study was approved by the ethical committee of the School of Dentistry, Universidad Científica del Sur, Lima, Perú.

Sample characteristics

The sample included 90 pre-treatment lateral cephalograms of Latin-American individuals (45 male, 45 female). These cases were part of a previously published [15] sample of cases. All the cephalograms were taken at maximum intercuspidation with the lips at rest in subjects aged 15 to 30 years old (21.50 ± 4.48). Imaging was performed with a digital cephalometric panoramic equipment (ProMax®, Planmeca, Finland) with settings set at 16 mA, 72 kV, and 9.9 s. Cephalometric analyses were performed digitally by two calibrated examiners with MicroDicom viewer software (version 0.8.1; Simeon Antonov Stoykov, Sofia, Bulgaria), without magnification, at a scale of 1:1.

Subjects with previous orthodontic treatment, tumors, infection or prosthetic molar reconstruction in the maxillary molar region and without maxillary third molars (extracted or missing) or any other missing/extracted permanent teeth were not considered.

Although a convenience sample of available records was used, sample size was calculated to demonstrate external validity. The sample size was calculated considering a mean difference of 10° in the maxillary second molar sagittal inclination as a clinically relevant difference between groups with and without MPDD. A standard deviation of 4° was considered (obtained from a preliminary pilot study) with a two-sided significance level of 0.01 and a power of 90 %. Although a minimum of five subjects per group was required, at least eight subjects per group were available. The calculated sample was 30 subjects; however, data from 90 subjects that met the selection criteria in a reference center of imaging were included.

Sample grouping

The study sample included six groups categorized according to their MPDD condition (present or absent) and to their sagittal skeletal facial growth patterns (classes I, II, or III) [16–19] (Table 1).

The definitions of the cephalometric points, distances, and angles [18–22] between them are shown in Table 2.

All subjects had a skeletal open bite (FMP angle greater than 26°, ODI lower than 72°, and lower anterior facial height greater than 67 mm) (Table 3).

Therefore, the groups were set as follows:

-

ο Open bite class I group with maxillary posterior discrepancy OBCIG-PD (n = 18): ANB angle between 0° and 5°, antero posterior dysplasia indicator (APDI) of 81.4° ± 4°, angle class I malocclusion, bilateral class I molar relations, overjet between 1 to 5 mm, negative overbite greater than 0.5 mm, and diagnosed with maxillary posterior discrepancy

-

ο Open bite class I group without maxillary posterior discrepancy (OBCIG-WPD) (n = 10): the same with the OBCIG-PD, but without posterior discrepancy

-

ο Open bite class II group with maxillary posterior discrepancy (OBCIIG-PD) (n = 19): ANB > 5°, APDI < 75°, angle class II-1 malocclusion, bilateral class II molar relations, overjet greater than 5 mm, negative overbite greater than 0.5 mm, and diagnosed with maxillary posterior discrepancy

-

ο Open bite class II group without maxillary posterior discrepancy (OBCIIG-WPD) (n = 22): the same with the OBCIIG-PD, but without posterior discrepancy

-

ο Open bite class III group with maxillary posterior discrepancy (OBCIIIG-PD) (n = 13): ANB < 0°, APDI > 88°, angle class III malocclusion, bilateral class III molar relations, overjet lower than −1 mm, negative overbite greater than 0.5 mm, and diagnosed with maxillary posterior discrepancy

-

ο Open bite class III group without maxillary posterior discrepancy (OBCIIIG-WPD) (n = 8): the same with the OBCIIIG-PD, but without posterior discrepancy

When both cephalometric methods (ANB and APDI) to diagnose sagittal skeletal facial growth pattern did not agree an additional evaluation that included the analysis of skeletal facial profile (sagittal relationship of the points N, A, and Pg), overjet, anteroposterior malocclusion, and soft profile convexity was considered before making a decision to which sagittal malocclusion group to assign any included case. All cephalometric radiographs were evaluated randomly.

Maxillary posterior dentoalveolar discrepancy (MPDD)

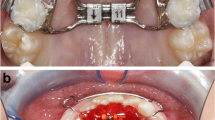

The dichotomous primary diagnosis of maxillary posterior discrepancy was made through radiographic evaluation by two calibrated examiners (LEAG, AADC). When the eruption of the maxillary third molar was apparently blocked by the presence of the erupted second, a maxillary posterior discrepancy was deemed present (Figs. 1 and 2).

In addition, for statistical analysis purposes, the ratio of the anterior maxillary base length A′6′ to the maxillary base length A′P′ (A′6/ A′P′) was also calculated as a continuous variable that reflects maxillary posterior discrepancy (Fig. 3, Table 2). If the radio of the anterior maxillary base length A′6′ to the maxillary base length A′P′ (A′6/ A′P′) was greater than 0.46, then a maxillary posterior discrepancy was suggested [6, 9, 19]

Maxillary molar sagittal angulation

The sagittal angulations of maxillary first and second molars were measured by the angle formed by the molar axis (intercuspid groove—root bifurcation) and the palatal plane (Fig. 4).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Ver.22 for Windows (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Data distribution normality was according to Shapiro-Wilk tests. An independent T test was performed to determine differences between two groups classified by the MPDD condition (present or absent) and sagittal malocclusion. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. A principal component analysis (PCA) was used to reduce the number of variables considered during the multivariate analysis. Finally, a multivariate analysis (MANCOVA) test was applied considering the effect of SNB, ANB, APDI, A′P′, ratio (A′6′/A′P′), overbite, lower anterior facial height, ratio facial height, maxillary posterior discrepancy, and sex (reduced by the PCA from the initial cephalometric variables) on the molar sagittal angulations (outcome variable). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all the tests.

Results

Reliability

Inter and intra-examiner reliability was assessed with the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC). All cephalometric values were greater than 0.979 (CI 95 % 0.954–0.999). In addition, the Dahlberg error was less than 1° for all angular measurements and 1 mm for all lineal measurements. All the cephalometric tracings were made with at least a 1-month interval between them and were performed by the same two different examiners.

Outcome variables

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the six groups by skeletal facial growth pattern and maxillary posterior discrepancy.

Descriptive statistics of the outcome variables can be found in Table 4. The maxillary first and second molar angulations in individuals with maxillary posterior discrepancy had a major distal crown tipping. The maxillary first molar angulation in the OBCIG-PD was 79.74° ± 4.69° and OBCIG-WPD was 88.41° ± 4.19° (p < 0.001), in the OBCIIG-PD was 74.17° ± 6.15° and OBCIIG-WPD was 83.67° ± 5.55° (p < 0.001), and in the OBCIIIG-PD was 82.85° ± 5.50° and OBCIIIG-WPD was 89.58° ± 1.94° (p = 0.004). The maxillary second molar angulation in the OBCIG-PD was 71.04° ± 4.99° and OBCIG-WPD was 82.94° ± 7.75° (p < 0.001), in the OBCIIG-PD was 61.98 ± 7.80° and OBCIIG-WPD was 79.27° ± 7.74° (p < 0.001), and in the OBCIIIG-PD was 71.39° ± 7.25° and OBCIIIG-WPD was 85.59° ± 1.71° (p < 0.001).

For the final analysis, the sample was separated into two groups according to MPDD (present = 50, absent = 40), trying to know the influence of MPDD in all types of malocclusion with open bite on the angulation of the upper molars. We also found significant differences between the two groups, p < 0.001 (Table 5).

Through a PCA (Table 6), it was determined that ANB, FMP, and ODI, as well as SNA, and A′P′, equally A′6′, and ratio (A′6′/A′P′) were significantly associated in this sample. SNB, ANB, APDI, A′P′, ratio (A′6′/A′P′), overbite, lower anterior facial height, ratio facial height maxillary posterior discrepancy, and sex were obtained after the reduction of the number of variables considered and were used in the MANCOVA. Significance was only found for maxillary posterior discrepancy (p < 0.001), APDI (p = 0.001), and ratio (A′6′/A′P′) (p = 0.026) for maxillary first molar angulation and APDI (p = 0.011) and maxillary posterior discrepancy (p < 0.001) for maxillary second molar angulation (Table 7).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of MPDD on the sagittal angulation of maxillary molars in skeletal open bite subjects. Overall, it was found that MPDD was associated with a significant mesial angulation of the second and first molar roots with a concurrent simultaneous distal angulation of the associated crowns. The findings are clinically relevant as they allow clinicians to consider these associations when facing patients with a potential MPDD. Their treatment decisions could be affected based on the degree of third molar angulation and how the erupted first and second molars are distally angulated in such cases. Distal molar movement in class II malocclusions should be careful in such scenario as this type of movements tends to distally angulate molar crowns. The method utilized to diagnose maxillary posterior discrepancy used a radiographic visual assessment by two calibrated examiners (LEAG, AADC), where the sagittal maxillary length and the portrayed trajectory of eruption of the third molars were considered. An unfavorable maxillary third molar eruption angulation would likely imply impaction (Figs. 1 and 2). In the literature, it has been proposed that maxillary posterior discrepancy should be determined by the ratio between the space from point A′ to mesial of the maxillary first molar, in relation to the space from point A′ to the most posterior point of the maxillary tuberosity [6, 9, 19]. When this ratio is increased, the chances of third molars having space for their eruption are diminished (Fig. 3).

The expected results, based on Kim [8] and Sato [9] hypothesis, were that there should be an increase in the mesial inclination of maxillary first and second molars (involving their crowns) that could promote posterior teeth interferences and therefore create a potential open bite scenario. However, the results of the current study suggested that maxillary molars showed more distally inclined crowns in the posterior discrepancy group. All the groups with posterior discrepancy showed significantly more distal molar crown angulation. This phenomenon supports the second hypothesis that the pressure from the erupting maxillary third molar against the anteriorly positioned molars may generate a major mesial displacement of the second and first molars roots with a concurrent simultaneous distal angulation of the associated crowns. These findings are in concordance with previous findings [1] where impacted third molars were observed to produce a distal angulation effect on the adjacent molars (involving their crowns) in subjects without open bite. Similar findings were observed in other studies [4, 23] showing that in high-angle cases, a greater degree of distal angulation of first molars was found. The latter suggested natural dentoalveolar compensation as potential explanation for the results.

Limitations

In this study, a maxillary posterior dentoalveolar discrepancy (defined in this study as an apparent lack of space for a complete maxillary third molar eruption) could be considered equivalent to maxillary third molar impaction.

A longitudinal cohort design would generate stronger data to support or refute the evaluated hypothesis and could use CBCT if possible, trying to avoid the superimpositions, although in this paper were excluded radiographs that showed evidently this problem.

Since open bite individuals without maxillary posterior discrepancy could have unerupted third molars with available space and good eruption pattern or third molars in occlusion, ideally, a study considering the maxillary molars inclination using open bite individuals with posterior discrepancy and open bite individuals with fully erupted third molar should follow-up. Results of such studies may or not support this study’s conclusion.

Previously, two studies [1, 24] used complete root formation with the highest part of third molar below the cervical line of second molar as a criterion for third molar impaction, but they do not consider the direction of eruption that is likely directly related to the impaction potential. In addition, the third molar’s roots are not fully formed until 20 to 22 years of age [24]. Accordingly, third molar impaction could be over diagnosed when examining subjects younger than 20 years old. In the current study, the subjects were between 15 to 30 years old. This could be considered a weakness, but it was, at least partially, controlled considering the eruption trajectory of third molar crowns as an independent factor from complete root formation.

The association between the severity of maxillary molar crown distal inclination and the degree of MPDD was not evaluated in this study.

Conclusions

The maxillary posterior dentoalveolar discrepancy generates a major mesial displacement of the second and first molar roots with a concurrent simultaneous distal angulation of the associated crowns in individuals with skeletal open bite.

Abbreviations

- MPDD:

-

Maxillary posterior dentoalveolar discrepancy

- PD:

-

Posterior discrepancy

References

Badawi Fayad J, Levy JC, Yazbeck C, Cavezian R, Cabanis EA. Eruption of third molars: relationship to inclination of adjacent molars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2004;125:200–2.

Stanaityté R, Trakiniené G, Gervickas A. Lower dental arch changes after bilateral third molar removal. Stomatologija. 2014;16:31–6.

Liao CH, Yang P, Zhao ZH, Zhao MY. Study on the posterior teeth mesiodistal tipping degree of normal occlusion subjects among different facial growth patterns. West China J Stomatol. 2010;28:374–7.

Su H, Han B, Li S, Na B, Ma W, Xu TM. Compensation trends of the angulation of first molars: retrospective study of 1403 malocclusion cases. Int J Oral Sci. 2014;6:175–81.

Merrifield LL, Klontz HA, Vaden JL. Differential diagnostic analysis system. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1994;106:641–8.

Sato S. Alteration of occlusal plane due to posterior discrepancy related to development of malocclusion—introduction to denture frame analysis. Bull Kanagawa Dent Coll. 1987;15:115–23.

Sato S, Takamoto K, Suzuki Y. Posterior discrepancy and development of skeletal class III malocclusion: its importance in orthodontic correction of skeletal class III malocclusions. Orthodontic Review. 1988;2:16–29.

Kim YH. Anterior openbite and its treatment with multiloop edgewise archwire. Angle Orthod. 1987;57:290–321.

Sato S. An approach to the treatment of malocclusion in consideration of dentofacial dynamics. Tokyo: Torin Books; 1991. In Japanese.

Kim YH, Han UK, Lim DD, Serraon ML. Stability of anterior openbite correction with multiloop edgewise archwire therapy: a cephalometric follow-up study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;118:43–54.

Gavazzi M, De Angelis D, Blasi S, Pesce P, Lanteri V. Third molars and dental crowding: different opinions of orthodontists and oral surgeons among Italian practitioners. Progress in Orthodontics 2014, doi: 10.1186/s40510-014-0060-y

Costa MG, Pazzini CA, Pantuzo MC, Jorge ML, Marques LS. Is there justification for prophylactic extraction of third molars? A systematic review. Braz Oral Res. 2013;27:183–8.

Zawawi KH, Melis M. The role of mandibular third molars on lower anterior teeth crowding and relapse after orthodontic treatment: a systematic review. Sci World J. 2014;2014:615429.

Stanaityté R, Trakiniene G, Gervickas A. Do wisdom teeth induce lower anterior teeth crowding? A systematic literature review. Stomatologija. 2014;16:15–8.

Arriola-Guillén LE, Aliaga-Del Castillo A, Pérez-Vargas LF, Flores-Mir C. Influence of maxillary posterior discrepancy on upper molar vertical position and facial vertical dimensions in subjects with or without skeletal open bite. 2015. Eur J Orthod. 1-8, doi:10.1093/ejo/cjv067

Steiner C. Cephalometrics for you and me. Am J Orthod. 1953;39:729–55.

Kim YH, Vietas JJ. Anteroposterior dysplasia indicator: an adjunct to cephalometric differential diagnosis. Am J Orthod. 1978;73:619–33.

Kim YH. Overbite depth indicator with particular reference to anterior open-bite. Am J Orthod. 1974;65:586–611.

Celar AG, Freudenthaler JW, Celar RM, Jonke E, Schneider B. The denture frame analysis: an additional diagnostic tool. Eur J Orthod. 1998;20:579–87.

Janson G, Crepaldi MV, de Freitas KM, de Freitas MR, Janson W. Evaluation of anterior open-bite treatment with occlusal adjustment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;134:10–1.

McNamara Jr JA. A method of cephalometric evaluation. Am J Orthod. 1984;86:449–69.

Jarabak JR, Fizzell JA. Technique and treatment with light wire edgewise appliances. Saint Louis: CV Mosby; 1972.

Chang YI, Moon SC. Cephalometric evaluation of the anterior open bite treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1999;115:29–38.

Kim TW, Artun J, Behbehani F, Artese F. Prevalence of third molar impaction in orthodontic patients treated nonextraction and with extraction of 4 premolars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;123:138–45.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Cientifica del Sur University, where the measurements were performed.

Authors’ contributions

LEAG participated in the study conception, the data collection, the manuscript formatting, and the statistical analysis. AADC participated in the study conception, the data collection, and the manuscript formatting. CFM participated in the manuscript formatting, the statistical analysis, and the data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Approved by the ethical committee of the School of Dentistry, Universidad Científica del Sur, Lima, Perú.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Arriola-Guillén, L.E., Aliaga-Del Castillo, A. & Flores-Mir, C. Influence of maxillary posterior dentoalveolar discrepancy on angulation of maxillary molars in individuals with skeletal open bite. Prog Orthod. 17, 34 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-016-0147-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-016-0147-8