Abstract

This study attempts to arrive at the vital factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions and establish a model with the help of the Pareto principle. In the first stage, a thorough literature review on the factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions was conducted which revealed a number of variables that influence or are responsible for the formation of social entrepreneurial intentions. In the second stage, a quality tool “Pareto analysis” was used to identify and propose “vital few” factors, by applying the 80:20 rule. Lastly, the study proposes a comprehensive model of social entrepreneurial intention formation. (a) The results of this study will be helpful in further research on the subject by providing a ready literature review on the subject, (b) the model can be used by fellow researchers in related research works, and (c) the resulting appropriate factors may be inculcated in curriculum of academic programs, experiential learnings, and trainings related to social entrepreneurship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social entrepreneurs and social entrepreneurship

Scholars in the field have taken different approaches to define the phenomena of social entrepreneurship. However, all the definitions intersect at the common motive of creation of social value through innovative solutions. This social value either comes as a benefit to the society or as a solution to prevailing social problems.

Dees (1998) describes social entrepreneurs as change agents in the social sector. Social entrepreneurs adopt a mission to create social value in addition to the private value. They recognize new opportunities and relentlessly follow them to serve this mission. They engage in a process of continuous innovation, adaptation, and learning and act boldly without being limited by resources currently in hand. Social entrepreneurs also exhibit a heightened sense of accountability to the constituencies served and for the outcomes created (Dees, 1998).

A similar definition based on the context of mission and opportunity recognition has been given by Sullivan Mort, Weerawardena, and Carnegie (2002), who describe social entrepreneurship as a multidimensional construct that involves the expressions of entrepreneurially virtuous behavior to achieve the social mission, a coherent unity of purpose and action in the face of moral complexity, and the ability to recognize social value creating opportunities and key decision-making characteristics of innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking.

Alvord, Brown, and Letts (2004) refer to social entrepreneurship as a means of achieving sustainable social transformations by mobilizing ideas, capacities, resources, and social arrangements. It is about solving social problems by creating innovative solutions (Alvord et al., 2004). Adding further on the context of innovation and sustainability, Mair and Noboa (2006) have defined social entrepreneurship as the innovative use of resource combinations to pursue opportunities aiming at the creation of organizations and/or practices that yield and sustain social benefits. Similarly, Mair and Marti (2006) define social entrepreneurship as a process involving the innovative use and combination of resources to pursue opportunities to catalyze social change and/or address social needs.

According to Austin, Stevenson, and Wei-Skillern (2006), social entrepreneurship is an innovative activity that creates social value and can occur within or across the nonprofit, business, and public sectors. Nevertheless, social entrepreneurship means different things to different people (Dees, 1998). According to Zahra, Rawhouser, Bhawe, Neubaum, and Hayton (2008), this has created confusion in the literature. Zahra et al. (2008) further define social entrepreneurship as the activities and processes undertaken to discover, define, and exploit opportunities in order to enhance social wealth by creating new ventures or managing existing organizations in an innovative manner. Social wealth is defined broadly to include economic, societal, health and environmental aspects of human welfare (Zahra et al., 2008).

For the purpose of the present study, we define social entrepreneurship as “entrepreneurial activity undertaken by an individual or a group of individuals to identify a social concern and develop a sustainable solution to the same in terms of social wealth”.

Economic implications of social entrepreneurship

The Canadian Centre for Social Entrepreneurship (2001) defines the phenomena of social entrepreneurship as a set of dual bottom line initiatives. This dual bottom line refers to benefit generated in terms of economic as well as social returns. Social entrepreneurship being one of the vehicles catering to the social economic problems like poverty and unemployment definitely has a positive impact on citizens’ economic and social freedom. According to Lombard and Strydom (2011), social entrepreneurship provides the opportunity to create an inclusive model of economic development through which underprivileged section of the society can be empowered and can work towards their own development. Social entrepreneurs can act as change agents and help in the integration of social and economic development projects through community development. Jilenga (2017) states that the social enterprise sector is one of the fundamental drivers of economic change. Through the production of value-oriented goods and services, the social enterprises can explore and grow market opportunities that would not exist otherwise in and for particularly underprivileged communities.

Social entrepreneurship is recognized in Europe as one of the key areas that provide employment and in turn facilitate in battling social exclusion and help in economic development (Loku, Gogiqi, & Qehaja, 2018).

Also, social entrepreneurship, by the virtue of being a subset of entrepreneurship, is bound to deliver solutions in problem areas like unemployment and poverty.

Social entrepreneurial intentions (SEI)

Sutton (as cited in Fini, Grimaldi, Marzocchi, & Sobrero, 2009) acknowledged the relevance of intentions in management literature. While Ajzen (1991) stressed on the importance of intentions in predicting the individual behaviors, Mitchel (1981) described how intentions are relevant in determining the organizational outcomes like development, survival, and growth. Thus, the role of intentions and their predictability assumes importance for entrepreneurs and managers (Tubbs & Ekeberg, 1991). Krueger and Deborah Brazeal (1994) mention that intentions are the best predictors of particularly rare and hard to observe behaviors. New venture creation is one such behavior (Bird, 1988). Fini et al. (2009) describe entrepreneurial intention as a cognitive representation of the actions to be implemented by individuals to display entrepreneurial activity. Thompson (2009) suitably defines entrepreneurial intention as a self-acknowledged conviction of a person that they intend to set up a new business. Study of intentions of prospective entrepreneurs in pre-founding phases may enable behavior prediction (Krueger, 2003). Krueger further states that all planned behavior is intentional and human behavior is either a response to a stimulus or planned. Entrepreneurship is a planned behavior as it is based on a voluntary effort and no action takes place without first having an intention that leads to it (Krueger, 2003). Hence, entrepreneurial intentions should be viewed as the first step towards the foundation of entrepreneurship (Lee & Wong, 2004).

People with SEI aim to create social value (Dees, 2001 cited in Bosch, 2013). Ernst (2011) defines SEI as a “self-acknowledged conviction by a person that they intend to become a social entrepreneur and consciously plan to do so at some point in the future.” Prieto, Phipps, and Friedrich (2012) regard SEI as an individual’s intention to create a social enterprise to bring about a social change through innovation. As regards social entrepreneurship, intentions can be defined as aspiration of an individual to set up social enterprise (Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016). In simple words, SEI can be understood as an individual’s objective to start an organization to create a social change in the society (Bosch, 2013; Chipeta & Surujlal, 2017; Prieto, 2010; Prieto et al., 2012).

The current study attempts to conceptualize a holistic model of social entrepreneurial intentions based on the theory of planned behavior. The proposed model details the determinants and antecedents of social entrepreneurial intentions and the interplay among them.

Thus, the research question for the current study can be stated as “what are the vital factors that influence social entrepreneurial intention formation and how?”

Literature review

Factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions

As social entrepreneurship gains increasing attention in practice and academia, it becomes important to dive into the dynamics and processes involved in intent development for becoming a social entrepreneur. In simple words, why would somebody intend to become a social entrepreneur? Many researchers around the world have worked on factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions, naming them as determinants, antecedents, or simply factors. Mair and Noboa were one of the first researchers in the field of social entrepreneurial intentions. Over the years, other researchers either built on theory given by Mair and Noboa (2005) or proposed new models for social entrepreneurial intentions based on the theoretical frameworks like the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) and entrepreneurial event model (Shapero & Sokol, 1982). The complete literature review of factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions has been done in a tabulated format presented in Table 1 that also lists the number of studies along with the variables proposed as factors responsible for influencing or formation of social entrepreneurial intentions.

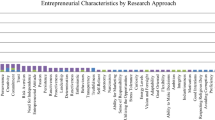

The “Pareto analysis of factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions” section explains the process of Pareto analysis conducted on the total number of factors extracted from the above studies. The results of the Pareto analysis shall be helpful in selecting the factors for creating the model of social entrepreneurial intention formation (Fig. 1).

Pareto chart of factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions (author’s own). The figure presents the result of the Pareto analysis technique in the form of a Pareto chart. The intersection of ~ 80% (79.62%) between the two axes occurs for the variable “perceived feasibility.” Hence, variables starting from “personality” till “perceived feasibility” are being taken as vital few factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions

Intention models in social entrepreneurship research

The two widely adopted models for intentions research in entrepreneurship are the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) and the model of entrepreneurial event (Shapero & Sokol, 1982). Krueger and Deborah Brazeal (1994) later made an attempt to integrate both these models and established the model of entrepreneurial potential.

Theory of planned behavior (TPB)

According to the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991), there are three conceptually independent determinants of intentions (Fig. 2). These are (i) attitude towards behavior, (ii) subjective norm, and (iii) perceived behavioral control. The attitude towards behavior refers to the extent of a person’s favorable or unfavorable evaluation or appraisal of the behavior in question. Subjective norm is a social factor that refers to the social pressure to perform or not perform the behavior. Perceived behavioral control is the level of ease or difficulty in performing the behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Further, Ajzen (1991) states that these three determinants of intentions symbolize individuals’ control over their behavior. With the required resources and opportunities, coupled with intentions, one can succeed in performing the desired behavior (Ajzen, 1991).

Theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991). The theory of planned behavior was proposed by Icek Ajzen in 1991. This concept states that an individual’s behavioral actions are shaped by attitude towards behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control

Previous studies on application of theory of planned behavior in studying social entrepreneurial intentions

Ajzen (1991) suggests extension of TPB (Ernst, 2011). These extensions can bring out additional insights in the area. Several studies that have extended and modified the TPB model in different contexts for studying social entrepreneurial intentions.

One of the earliest works on empirically testing the TPB model to determine social entrepreneurial intentions was done by Ernst (2011). Ernst (2011) extended the theory of planned behavior by adapting the three attitudinal level elements in the context of social entrepreneurial intentions. Ernst extended the model by introducing the antecedents of attitudinal level constructs as social entrepreneurial personality, social entrepreneurial human capital, and social entrepreneurial social capital and Prieto et al. (2012) on TPB and The Center for Leadership Development’s Assess, Challenge, Support (ACS) model. Combining these two models, Prieto et al. (2012) made an attempt to create a framework for social entrepreneur development. The authors evaluated the social entrepreneurial intentions scores of African-American and Hispanic college students and observed these intentions to be very low. They proposed that their framework could serve as a guide for increasing social entrepreneurial intentions.

In his doctoral thesis, Bosch (2013) examined the direct effect of personal values like self- enhancement, self-transcendence, conservation, and openness to change on intentions to indulge in commercial and social entrepreneurship. TPB has been used as the theoretical framework in further examining the mediating effect of attitude over the relationship between these personal values and entrepreneurial intent (Bosch, 2013).

Hayek, Williams, Randolph-Seng, and Pane-Haden (2013) state that the social psychology literature suggests the inclusion of personal norms in predicting moral intentions. In this paper, by including personal norms along with attitude attempt to extend the TPB framework to analyze the life story of Juliette Gordon (Daisy) Low who was the founder of the Girls Scouts, the largest association of girls in the world (Hayek et al., 2013).

Chipeta (2015) conducted a study, as part of his master thesis, to examine the social entrepreneurial intentions among the university students in Gauteng province of South Africa. This master thesis and subsequent studies—Chipeta, Koloba, and Surujlal (2016) and Chipeta and Surujlal (2017)—used TPB as the theoretical framework and tested the role of attitude towards behavior and perceived behavioral control along with attitude towards entrepreneurship education, proactive personality, and risk-taking propensity. Interestingly, whereas Chipeta (2015) found that there was no significant role of gender and age in social entrepreneurial intentions among students, a similar study by Chipeta et al. (2016) concluded that there were significant differences in terms of the influence of gender and age on social entrepreneurial intentions and attitude towards entrepreneurship.

Yang, Meyskens, Zheng, and Hu (2015) examine the difference in the concept of social entrepreneurship across two different cultures, i.e., the USA and China. In this study, Yang et al. (2015) use the theory of planned behavior to evaluate the influence of culture on social entrepreneurial intentions. The results of the study show that subjective norms exert higher influence and behavioral attitudes exert lower influence over social entrepreneurial intentions in China than in the USA.

Rapando (2016) made an attempt to study the effect of environmental factors on social entrepreneurial intentions through the TPB model. According to Rapando (2016), environmental factors like high poverty levels, high crime rates, low incomes levels, lack of access to cheap capital, low access to both the international and local market, and lack of both human and intellectual capital hamper the social entrepreneurial intentions.

Politis et al. (2016) provide empirical evidence on the creditworthiness of the theory of planned behavior in the prediction of commercial as well as social entrepreneurial intentions while disproving the personality traits theory and the theory of contextual influence (Politis et al., 2016). Cavazos-Arroyo et al. (2017) investigate the role of attitude, subjective norms, and entrepreneurship self-efficacy in influencing intentions of beginning a social entrepreneurship venture among Mexico residents. The study also suggests that social innovation orientation can be strongly predicted by social vision along with financial returns interest and may not be affected by sustainable values (Cavazos-Arroyo et al., 2017). Cavazos-Arroyo et al. (2017) also approve of a positive effect of social innovation orientation on social entrepreneurial attitude. The study uses TPB as a theoretical framework and examines the effect of attitude and subjective norms on social entrepreneurial intentions. However, the authors choose to replace perceived behavioral control by self-efficacy in their research model. The results of the study show that while subjective norms come out to be the strongest predictor of social entrepreneurial intentions in Mexico, these are also positively influenced by attitude and entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Cavazos-Arroyo et al., 2017).

A study by Tiwari, Bhat, and Tikoria (2017) aims at investigating social entrepreneurial intentions among undergraduate students in India. The study used the theory of planned behavior as the research framework. Here, in addition to the original determinants of intentions in TPB, authors introduced new antecedents like emotional intelligence, creativity, and moral obligation. Tiwari et al. (2017) concluded that while emotional intelligence and creativity are strong antecedents of attitude towards behavior, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and social entrepreneurial intentions, moral obligation showed a somewhat weak relationship with subjective norms.

Entrepreneurial event model

The entrepreneurial event model developed by Shapero and Sokol (1982) comprises of three elements—displacement, perceived desirability, and perceived feasibility that lead to intention formation (Fig. 3). According to Shapero’s model, human behavior is guided by inertia until something disturbs or displaces it (Krueger & Deborah Brazeal, 1994). Displacement is the trigger that causes a change in behavior (Shapero & Sokol, 1982). Ayob, Yap, Sapuan, and Rashidd (2013) explain that this displacement can be negative like lack of job satisfaction or positive such as rewards. While perceived desirability refers to the attractiveness of starting an enterprise for an individual, perceived feasibility is the perception of an individual towards his or her capability of starting an enterprise (Shapero & Sokol, 1982). The perception of desirability is influenced by personal attitude, values, and feelings that result from social environment of an individual like family, friends, and colleagues (Shapero & Sokol, 1982). The factors like knowledge, human, and financial resources, on the other hand, influence the perceived feasibility (Shapero & Sokol, 1982).

Entrepreneurial event model (Shapero & Sokol, 1982). Shapero and Sokol (1982) developed a model on variables affecting entrepreneurial intentions. They explained that desirability, feasibility, and a propensity to act are the major factors that control an individual’s intention to create a new venture

Entrepreneurial potential model

The entrepreneurial potential model (Krueger & Deborah Brazeal, 1994) was developed by integrating the concepts of both the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) and the entrepreneurial event model (Shapero & Sokol, 1982) (Fig. 4). Krueger & Deborah Brazeal (1994) explain that the model of entrepreneurial potential streamlines the previous theories by matching up perceived desirability to attitude and social norms and perceived feasibility to perceived behavior control. Krueger & Deborah Brazeal (1994) further state that the choice of the resulting behavior depends on the relative credibility of alternative behaviors supported by the propensity to act. The propensity to act, as conceptualized by Shapero and Sokol (1982), is a stable personality characteristic (as cited in Krueger & Deborah Brazeal, 1994). It is thus required that the behavior has to appear both desirable and feasible in order to seem credible. Potential, as explained by Krueger & Deborah Brazeal (1994), is latent and is causally and temporally prior to intentions. Shapero and Sokol (1982) define potential as the preexisting preparedness to accept an opportunity, and an entrepreneurial event occurs when this potential is followed by a precipitating event or displacement (Krueger & Deborah Brazeal, 1994).

The entrepreneurial potential model (Krueger & Deborah Brazeal, 1994). The entrepreneurial potential model (Krueger & Deborah Brazeal, 1994) was developed by integrating the concepts of both the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) and the entrepreneurial event model (Shapero & Sokol, 1982). Krueger and Deborah Brazeal (1994) explain that the model of entrepreneurial potential streamlines the previous theories by matching up perceived desirability to attitude and social norms and perceived feasibility to perceived behavior control. Krueger and Deborah Brazeal (1994) further state that the choice of the resulting behavior depends on the relative credibility of alternative behaviors supported by the propensity to act

Previous studies on application of entrepreneurial event model and entrepreneurial potential model in studying social entrepreneurial intentions

Mair and Noboa (2005) were one of the first to propose that perceived desirability and perceived feasibility influence the behavioral intentions behind the creation of a social enterprise. In this case study on a social entrepreneur, Mair and Noboa (2005) adapt the model of entrepreneurial potential (Krueger & Deborah Brazeal, 1994) and translate it to social entrepreneurship. Mair and Noboa (2005) argue that social entrepreneurs like traditional ones also experience perceptions of feasibility and desirability and propensity to act. In addition to this, the social entrepreneurs develop social sentiments, while variables like willpower, support, and opportunity construction are found to be important antecedents of perceptions of feasibility and desirability and propensity to act.

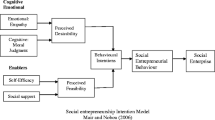

Mair and Noboa (2006) aimed at developing a parsimonious model of intention formation while building on the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) and Shapero & Sokol’s model of entrepreneurial event formation (1982). While antecedents like empathy and moral judgment affect the desirability, feasibility is facilitated by social support and self-efficacy beliefs (Mair & Noboa, 2006).

Adapting from the models of Shapero and Sokol (1982) and Krueger and Deborah Brazeal (1994), a study by Ayob et al. (2013) aims at examining the social entrepreneurial intention in view of an emerging economy (Fig. 5). As proposed by Ayob et al. (2013), their proposed conceptual model of social entrepreneurial intentions differs from the existing studies by adding the concepts of empathy and social entrepreneurship exposure as antecedents to perceived desirability and perceived feasibility, which in turn lead to social entrepreneurial intention.

The resulting model of social entrepreneurial intention formation (author’s own). The resulting model of social entrepreneurial intention formation is based on the theory of planned behavior. It consists of social entrepreneurial intention as the dependent variable. There are six independent variables (constructs) in the model out of which three variables belong to the theory of planned behavior

Orazio et al. (2013) investigate the determinants of commercial and social entrepreneurial intentions at the individual level. The study is an attempt towards defining the characteristics of prospective entrepreneurs and the process of venture creation, while at the same time differentiating the behavior of social entrepreneurs from traditional entrepreneurs. The study differentiates social entrepreneurial intentions from entrepreneurial intentions in the influence that social capital exerts on them.

Methodology

The objectives of this study are threefold—(i) to derive a wide list of factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions by conducting a thorough literature review, (ii) to conduct Pareto analysis and arrive at the list of vital few factors that affect social entrepreneurial intention formation, and (iii) to develop a model of social entrepreneurial intention formation by proposing relationships among these vital factors.

The methodology adopted for the study included an in-depth literature review of studies focusing on factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions. The studies so chosen are either empirical or review studies and the variables were statistically tested and validated in these studies. The literature review thus resulted in a wide list of factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions (Table 1). The next step in the methodology was to apply a quality tool—“Pareto analysis”—to this wide list of factors to arrive at the vital few among them. The details of the application of Pareto analysis in this study are given in the succeeding sections. Finally, literature was further mined to observe the relationships between the vital factors that resulted from Pareto analysis and develop propositions. These propositions then were used to draw a conceptual model of social entrepreneurial intention formation.

Pareto analysis

Pareto analysis is a decision-making technique in the field of statistics used to select a limited number of factors that give occurrence to a substantial overall effect (Talib, Rahman, & Qureshi, 2010). Pareto analysis, which is also known as 80:20 rule was developed by Vilfredo Pareto, an Italian economist. Karuppusami and Gandhinathan (2006) have described the process of conducting a Pareto analysis. First, the data or factors are sorted in descending order of the frequency of occurrences. The total frequency is then summed to 100%. The “vital few” factors occupy 80% of the occurrences. The rest of the factors correspond to 20% of the occurrences (Karuppusami & Gandhinathan, 2006). In the second stage, the results of the Pareto analysis are represented in the form of a chart, usually known as the Pareto chart. The chart presents the factors in ranked order in the form of a bar graph where bars represent the factors in descending order. It also includes a superimposing line graph that cuts an 80% cumulative percentage, in turn suggesting the vital few factors (Cervone, 2009).

Pareto analysis of factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions

Karuppusami and Gandhinathan (2006) conducted a Pareto analysis of critical success factors of total quality management. Later, Talib et al. (2010) conducted a Pareto analysis to arrive at critical success factors of total quality management specific to service industries. In another study, the Pareto principle was used to identify critical factors for effective implementation of the HACCP system (Fotopoulos, Kafetzopoulos, & Gotzamani, 2011). A similar study in the area of supply chain management was conducted by Ab Talib, Hamid, and Thoo in 2015, in which they identified critical success factors of supply chain management using the Pareto analysis technique.

Likewise, the Pareto analysis has been used in the identification of vital factors responsible for the occurrence of a phenomena. The present study has used Pareto analysis to identify vital factors responsible for the formation of social entrepreneurial intentions. This was done by analyzing the frequency of every possible factor in social entrepreneurial intentions literature. The complete process describing the use of Pareto analysis in the present study is detailed below.

To carry out the Pareto analysis of the factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions, we refer to the existing literature on the subject. Over the years, various authors have contributed to the field of social entrepreneurial intentions (refer to Table 1). The Pareto analysis compiled from 43 selected research papers is presented in Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 1. Further, Fig. 1 also presents a Pareto chart of factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions which indicate “vital few” factors that accounted for 80% occurrences in the study.

Further, it was observed during literature review that many factors fall under a broad construct, for example, willpower (Mair & Noboa, 2005), empathy (Mair & Noboa, 2006), proactive personality (Prieto, 2010), and risk-taking ability (Chaudary and Fatima, 2014), could be grouped under one broad construct of “personality.” Thus, some of these factors are presented under a single label (italic letters in Tables 1 and 2).

In this study, the total number of factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions extracted and grouped from all 43 studies taken for review was 28. The total frequency of occurrences of these 28 factors was found to be 157. After a Pareto analysis of these 28 factors, 9 vital few factors accounted for 80% (Table 2). The remaining 19 factors accounted for only 20% frequency of occurrences and are reported as “significant others” (Table 3).

Theoretical framework and model development

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) is a widely chosen and established intention model in social entrepreneurial intention (SEI) studies. Ernst (2011) states that TPB has also shown relevance in designing entrepreneurship education and training programs by identifying focus areas. Further, as Ajzen (1991) suggests, the TPB model can be extended based on the needs and settings of the study. Thus, we choose TPB as the theoretical framework for the present study.

The vital few factors resulting from the Pareto analysis (Table 2) are considered for the development of the model of social entrepreneurial intentions. Personality is undoubtedly the most important factor that leads to the intention formation for creating a social enterprise, followed by attitude towards behavior, subjective norms, social capital, human capital, perceived behavior control, self-efficacy, perceived desirability, and perceived feasibility. As also discussed earlier, Krueger and Deborah Brazeal (1994) explain the equivalencies of perceived desirability to attitude towards behavior and subjective norms, and perceived feasibility to perceived behavior control. Thus, the selection of TPB as the chosen framework with attitude towards behavior, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms as attitudinal level constructs eliminates perceived desirability and perceived feasibility from our list of vital few factors to avoid duplication of variables. Also, the concept of self-efficacy largely overlaps with perceived behavioral control (Krueger & Deborah Brazeal, 1994), thus eliminating self-efficacy also from our final list of factors.

For extension of TPB, Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) suggest that the additional variables can affect the intentions only through the three attitudinal level constructs, i.e., while these three variables—attitude towards behavior, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms can be modeled as determinants of intentions; the model can be extended by the addition of potential antecedents of these constructs themselves. The next section of the paper describes the stage-wise development of propositions and the model.

Propositions development

Attitude level constructs and social entrepreneurial intentions

Attitude towards behavior (ATB)

Bosch (2013) defines attitudes as an individual’s positive or negative evaluation towards creating an organization. In simple words, attitude towards becoming an entrepreneur is a person’s affective and evaluative perspective on advantages of becoming an entrepreneur (Bosch, 2013). Braga, Proença, and Ferreira (2014) in a survey found that the passion or personal interest in the entrepreneurial task is the inherent motivation of people who intent to become entrepreneurs. Ernst (2011) adapted ATB as attitude towards becoming a social entrepreneur. The classical model of theory of planned behavior as well the studies based on TPB framework accept a positive effect of ATB on intentions. Thus, more to the attractiveness of becoming a social entrepreneur is the expected raise in the respective intentions (Ernst, 2011). A recent study by Tiwari et al. (2017) describes ATB as a good or bad assessment of the behavior in question. While referring to it as a personal pull towards a targeted behavior, they maintain that it is the most important construct of intention in the TPB. Hence, for the purpose of this study, we adopt ATB as an attitude towards becoming a social entrepreneur (ATB-SE), i.e., the degree to which a person possesses positive or negative evaluation towards the idea of becoming a social entrepreneur. Therefore, we propose the following:

-

P1: ATB-SE will positively affect SEI

Perceived behavioral control (PBC)

Considering the definition of perceived behavioral control, Ernst (2011) refers to it as the most difficult construct in TPB. While Ajzen (1987) states that PBC is the perceived ease or difficulty of performing a particular behavior, Liñán and Chen (2009) described it as the ease or difficulty of becoming an entrepreneur itself. Ernst (2011) adapted PBC as the perceived behavioral control on becoming a social entrepreneur, i.e., the perception of ease or difficulty of becoming a social entrepreneur. Whereas Krueger Jr, Reilly, and Carsrud (2000) state that PBC overlaps with the construct of self-efficacy given by Bandura (1986), which is defined by Ajzen (1987) as the perceived ability to perform a target behavior, Krueger and Brazeal (1994) mention PBC as subsuming personal perceptions of a behavior’s feasibility. However, Ajzen (2002) clarifies and states that self-efficacy can be said to be a subset of PBC. A model on social entrepreneurial intention formation developed by Mair and Noboa (2006) includes perceived feasibility as a core construct responsible for the formation of intentions directly and as a mediator between self-efficacy and social support and behavioral intentions.

Almost all the intention studies till date in the field of social entrepreneurship that mention PBC assume that it has a positive impact on social entrepreneurial intentions (Bosch, 2013; Chipeta, 2015; Chipeta et al., 2016; Chipeta & Surujlal, 2017; Ernst, 2011; Hayek et al., 2013; Rapando 2016; Politis et al., 2016; Prieto et al., 2012; Tiwari et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2015). While considering PBC as one of the strongest predictors of intention, Tiwari et al. (2017) mention of PBC as a belief for carrying out a certain task and includes various activities required to perform the task. For the purpose of this study, we adopt PBC as perceived behavior control towards becoming a social entrepreneur (PBC-SE). Ernst (2011) also examines the relationship between perceived behavioral control and attitude towards behavior. The perception of ease or difficulty of performing an action can also lead to an individual’s positive or negative evaluation of that behavior.

Therefore, we propose the following:

-

P2: PBC-SE will positively affect ATB-SE

-

P3: PBC-SE will positively affect SEI

Subjective norms (SN)

Ajzen (1991) defines subjective norms as beliefs coming from the social environment of an individual such as approvals or disapprovals from social groups like family or friends for performing or not certain behaviors. Moorthy and Annamalah (2014) use the term “social norms” to denote subjective norms and define this construct as a function of the perceived normative beliefs of significant groups, such as family, friends, and co-workers, opinionated by the individual’s purpose to comply with each normative belief. According to Hockerts (2017), Mair and Noboa (2006) included moral judgment in their model as a proxy for perceived social norms of TPB, i.e., people tend to behave in a certain manner when they feel that the behavior in question complies with societal norms.

In their review of literature, Cavazos-Arroyo et al. (2017) states that even while the relation between SN and intentions is an important element of the TPB, the research till date has been somewhat inconclusive. Some investigations have found that SN is a significant yet weak predictor of intentions while others reported inconsistent results (Cavazos-Arroyo et al., 2017). Ernst (2011) adapted SN as subjective norms on becoming a social entrepreneur. While researchers in this area argue that subjective norm is a weak construct owing to weak results, the majority of studies have acknowledged measurement flaws as a reason behind it (Ernst, 2011). Nevertheless, subjective norms reflect the impact of community and suggest the desirability or undesirability of behaviors, thus, making it an interesting yet complicated component in the model (Moorthy & Annamalah, 2014). According to Tiwari et al. (2017), Indian society gives higher preference to collectivism, where reference groups influence the decision-making process of the individuals. Therefore, it becomes imperative to explore the role of SN in the prediction of social entrepreneurial intentions. For the purpose of this study, we adopt SN as subjective norms on becoming a social entrepreneur (SN-SE). Ernst (2011) also quotes previous studies that explore the relationships between subjective norms and attitude towards behavior. The perception on social entrepreneurship being more attractive can also be the result of social pressure being exerted on an individual.

Therefore, we propose the following:

-

P4: SN-SE will positively affect ATB-SE

-

P5: SN-SE will positively affect SEI

Adding antecedents of attitude level constructs

Social capital

Social capital has something to with interaction among people or institutions (Ernst, 2011). Thus, social capital relates to social structures to facilitate certain activities of the individuals within the structures (Coleman, 1988 cited in Ernst, 2011). Social capital refers to the resources and benefits people receive from knowing others in a network (Linan and Santos, 2007 cited in Ernst, 2011). Tran and Von Korflesch (2016) define perceived support as the assistance and encouragement expected by an individual from his or her personal network to become a social entrepreneur. They proposed a direct relation between perceived support and self-efficacy. Ernst (2011) suggested three sub-constructs of social capital, namely, perceived knowledge of institutions, perceived network, and perceived support. While it was found that perceived knowledge of institutions positively affected ATB-SE, PBC-SE, and SN-SE, no link was found between perceived network and PBC-SE and SN-SE. Interestingly, the relation between perceived network and ATB-SE was found to be negative. Perceived support was found to be positively related to SN-SE and not related at all with PBC-SE. Support in terms of finance is negatively related to ATB-SE whereas the other support was not found to be related at all (Ernst, 2011). Two categories of social capital were suggested by Linan and Santos (2007)—bonding social capital and bridging social capital (as cited in Ernst, 2011). While bonding social capital represents the strong links that an individual has in his close network like family and friends, bridging social capital refers to weak and irregular contacts with people or institutions in which a person does not actively indulge in (Ernst, 2011; Ip, Wu, Liu, & Liang, 2018; Liu, Ip, & Liang, 2018; D'Orazio et al., 2013). Orazio et al. (2013) found that bridging social capital influences perceived desirability of entrepreneurial intentions, but not that of social entrepreneurial intentions. However, bonding social capital was found to be positively related to perceived desirability of social entrepreneurial intentions (Orazio et al., 2013).

Ryzin, Grossman, DiPadova-Stocks, and Bergrud (2009) suggest that social capital supports social entrepreneurship but as well may result from it. According to Mair and Noboa (2006), entrepreneurs cannot succeed alone; rather, they need efficient networks to become successful. The social support needed by entrepreneurs is typically known as social capital, which results from social networks in the form of trust and cooperation (Hockerts, 2013; Hockerts, 2017; Mair & Noboa, 2006). Hockerts (2017) further states that in the context of social entrepreneurship, it can be assumed that the individuals will evaluate their backing and support from people in their personal network. For the purpose of this study, we adopt social capital as social entrepreneurial social capital (SC-SE) with three sub-constructs, namely, perceived knowledge of institutions, perceived network, and perceived support. Therefore, we propose the following:

-

P6: Perceived knowledge of institutions will be positively related to ATB-SE

-

P7: Perceived knowledge of institutions will be positively related to PBC-SE

-

P8: Perceived knowledge of institutions will be positively related to SN-SE

-

P9: Perceived network will be positively related to ATB-SE

-

P10: Perceived network will be positively related to PBC-SE

-

P11: Perceived network will be positively related to SN-SE

-

P12: Perceived support will be positively related to ATB-SE

-

P13: Perceived support will be positively related to PBC-SE

-

P14: Perceived support will be positively related to SN-SE

Human capital

Human capital consists of two factors—knowledge and skills. Both of these factors are imperative to become an entrepreneur (Shane et al., as cited in Ernst, 2011). Ernst (2011) further states that the two factors—knowledge and skills—both based on experience and education, have been used interchangeably in previous studies. Ernst (2011) suggested two constructs of social entrepreneurial social capital—perceived social entrepreneurial knowledge/experience and perceived social entrepreneurial skills. A number of studies in the field of social entrepreneurship intentions have mentioned human capital on similar lines like education (Jensen, 2014; Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016; Yiu, Wan, Ng, Chen, & Su, 2014), critical pedagogy (Prieto et al., 2012), training (Chinchilla & Garcia, 2017; Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016), previous job or business experience (Hockerts, 2013; Orazio et al., 2013), and prior experience with social problems (Liu et al., 2017), exposure to social entrepreneurship (Ayob et al., 2013), and social volunteering (Chinchilla & Garcia, 2017).

Ernst (2011) found that social entrepreneurial knowledge/experience has a positive influence on ATB-SE and PBC-SE, and social entrepreneurial skills have a positive influence only on PBC-SE. Ayob et al. (2013) found that exposure to social entrepreneurship is positively related to perceived desirability of starting social entrepreneurship projects. Hockerts (2013) measures prior experience as an individual’s previous experience working in a social sector organization. In this study, prior experience with social sector organization was found to be a predictor of social entrepreneurial intentions, while perceived social support, self-efficacy, moral obligation, and empathy mediated the relationship (Hockerts, 2013). Orazio et al. (2013) confirmed the influence of human capital, as previous business experience, on perceived desirability of social entrepreneurial intentions. For the purpose of this study, we adopt human capital as social entrepreneurial human capital (HC-SE) that includes the constructs of perceived social entrepreneurial knowledge and perceived social entrepreneurial skills.

Therefore, we propose the following:

-

P15: Perceived social entrepreneurial knowledge will be positively related to ATB-SE

-

P16: Perceived social entrepreneurial knowledge will be positively related to PBC-SE

-

P17: Perceived social entrepreneurial skills will be positively related to ATB-SE

-

P18: Perceived social entrepreneurial skills will be positively related to PBC-SE

Personality

Burger (2006) defines personality as an interpersonal process and a constant behavioral configuration, which is an integral part of the individual himself. The personality of an individual is a set of integrated traits responsible for emotional, cognitive, and behavioral patterns (Mount, Barrick, Scullen, & Rounds, 2005). According to Nga and Shamuganathan (2010), social entrepreneurs possess diverse personality traits defining their behaviors. While these traits are somewhat inherent, they are also developed through socialization and education. Further, the value and belief system is also responsible for the formation of a social entrepreneurial personality. Personality traits have an impact on the intentions and the decision-making process of an individual and on entrepreneurship at large (Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010).

Llewellyn and Wilson (2003) define personality traits as persistent and expected characteristics of a person’s behavior explaining differences in individual actions in the same settings. The risk-perception of an entrepreneur is also a function of his/her personality traits (Chaucin et al., 2007, as cited in Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010).

One of the most widely known and researched approaches to describe personality traits is the Big Five personality model introduced by Paul Costa and Robert McRae in 1985. According to this model, there are five traits of an individual’s personality, namely, agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness (Burger, 2006; Costa and McRae, 1992, as cited in Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016). Numerous authors have researched influence of Big Five personality traits on social entrepreneurial intentions and have found interesting results (Chaudary and Fatima, 2014; Ip et al., 2017; Ip et al., 2018; İrengün & Arıkboğa, 2015; Liu et al., 2018; Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010; Ryzin et al., 2009; Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016).

The following section discusses the Big Five personality traits.

Agreeableness

According to Tran and Von Korflesch (2016), agreeableness subsumes the tendencies to be sympathetic and cooperative. While a low level of agreeableness corresponds to characteristics of manipulation, self-centeredness, doubtfulness, and ruthlessness, persons possessing a higher level of agreeableness are often trusting, forgiving, caring, altruistic, and gullible (Costa and McRae, 1995, as cited in Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016). Sympathy and concern for others are qualities of a social entrepreneur, who care for people belonging to the underprivileged section of the society. In social relationships, agreeableness subsumes the virtues of patience, compassion, and empathy that help a social entrepreneur to deal with social problems effectively while developing a social network necessary for the creation of a social enterprise (İrengün & Arıkboğa, 2015; Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010; Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016). Miller, Grimes, McMullen, and Vogus (2012) mention compassion as a prosocial motivator characterized by emotional inclination towards the suffering of others. Thus, people with a high degree of agreeableness are more likely to indulge in social entrepreneurship. Nga and Shamuganathan (2010) found a positive relationship between agreeableness and social networks. Also, Mair and Noboa (2006) suggest that desirability to become a social entrepreneur is affected by a prosocial personality while perceived desirability, as discussed earlier, included the constructs of ATB and SN. Hence, we propose the following:

-

P19: Agreeableness trait of personality will be directly related to perceived network

-

P20: Agreeableness trait of personality will be directly related to ATB-SE

-

P21: Agreeableness trait of personality will be directly related to SN-SE

Conscientiousness

Nga and Shamuganathan (2010) state that the conscientiousness trait refers to diligence, conformity, and continuously maintaining high performance. Conscientious people have a strong sense of responsibility and need for achievement which makes them dependable in whatever they do. Conscientiousness has also been found to positively affect the existence of the firm in the long run (Ciavarella, Buchholtz, Riordan, Gatewood, & Stokes, 2004) whereas the need for achievement positively relates to the firm’s competitive advantage (Ong and Ismail, 2008 as cited in Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010). Ernst (2011) explains that the need for achievement is typical of entrepreneurs and is integrated within the personality of a social entrepreneur.

McClelland’s work in achievement motivation explains that people with a high level of need for achievement select work settings where they can have personal control over the process outcomes, especially entrepreneurship (cited in Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016). Willpower, a component of conscientiousness (Fitch & Ravlin, 2005), has been used in Mair and Noboa’s (2005) model of social entrepreneurial intentions. Willpower influences the propensity to act, which is the motivating tendency for a person who wants to start a business (Mair & Noboa, 2005). The field of social entrepreneurship is more challenging than commercial entrepreneurship, which means prospective social entrepreneurs need to be more responsible, hard-working, and have a high level of need for achievement (Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016). Ernst (2011) found that entrepreneurial personality that constitutes the need for achievement has no effect on the attitude towards social entrepreneurship and subjective norms. Further, Chaudary and Fatima (2014) found a positive relationship between conscientiousness and social networks. Therefore, we propose the following:

-

P22: Conscientiousness trait of personality will be directly related to perceived network

-

P23: Conscientiousness trait of personality will be directly related to ATB-SE

-

P24: Conscientiousness trait of personality will be directly related to SN-SE

Extraversion

Extraverted people are warm, optimistic, assertive, and sociable in their relationships (İrengün & Arıkboğa, 2015; Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010; Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016). Further, extraverted people are proactive and have a charismatic vision (Crant, 1996 cited in Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010). Social entrepreneurs are supposed to be extraverted as they need to deal with a diverse set of stakeholders (Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010). Proactivity is the deployment of one’s personal resources to launch a venture. Both commercial and social entrepreneurship involves proactive actions may include seeking opportunity, overcoming obstacles, and anticipating difficulties (Bargsted et al., 2013 cited in Kedmenec, Rebernik, & Peric, 2015). Proactivity is about bringing change not just expecting it and social entrepreneurs are people who are willing to change the environment regarding the social issues they are concerned with (Bateman & Crant, 1993 cited in Prabhu et al., 2016). Thus, it may be posited that people with a higher degree of extraversion may have higher intentions to pursue social entrepreneurship. Ernst (2011) found that entrepreneurial personality constitutes proactiveness and has no effect on the attitude towards social entrepreneurship or subjective norms. Further, Chaudary and Fatima (2014) observed a strong relationship between extraversion and social networks. Therefore, we propose the following:

-

P25: Extraversion trait of personality will be directly related to perceived network

-

P26: Extraversion trait of personality will be directly related to ATB-SE

-

P27: Extraversion trait of personality will be directly related to SN-SE

Neuroticism

The degree of neuroticism is defined as the level of emotional stability of a person (Yong, 2007 cited in Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010; Singh and DeNoble, 2003 cited in Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016). In other words, it is a factor that represents an individual’s balance in terms of his or her emotions (Burger, 2006 cited in İrengün & Arıkboğa, 2015). Highly neurotic individuals exhibit negative emotions such as mood swings, impulsive behavior, depressions, low self-esteem, anxiety, hostility, anger, and sadness (İrengün & Arıkboğa, 2015; Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010; Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016). Entrepreneurs, especially social entrepreneurs, face a great deal of pressure in establishing a new venture. They are often regarded as tough, optimistic, and balanced when faced with such social pressure and uncertainty (Locke, 2000 cited in Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016). Thus, social entrepreneurs can be regarded as people with a high degree of emotional stability and less neurotic as they manage limited resources and diverse stakeholders (Chaudary & Fatima, 2014). People with a high level of neuroticism are more likely to exert negative influence on the social networks (Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010). Therefore, we propose the following:

-

P28: Neuroticism trait of personality will be directly related to perceived network

Openness

Openness refers to a personality characteristic used to define an individual who is intellectually curious, imaginative, and exhibits creativity (Costa & McRae, 1995 cited in Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010, and Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016). The tendency exhibit creativity, curiosity, adventure, and receptiveness to novel experiences is also known as openness (Singh & De’Noble, 2003 cited in Tran & Von Korflesch, 2016). These qualities are significant for entrepreneurship and innovative change to deal with social problems. Hence, people high on openness to new experiences are more likely to become social entrepreneurs. Nga and Shamuganathan (2010), however, argue that overly inquisitive people may get bored with status-quo. This trait of openness is also found to negatively influence the long term sustainability of the firm (Ciavarella et al., 2004 cited in Nga and Shanmuganathan). Further, Chaudary and Fatima (2014) found the relationship between openness and social networks as insignificant. However, openness to new experience should also mean openness to dealing with new people.

Openness in entrepreneurship is generally considered synonymous with risk-taking ability (İrengün & Arıkboğa, 2015). Ernst (2011) found no link between entrepreneurial personality that subsumes risk-taking propensity and intentions to become a social entrepreneur. Chipeta and Surujlal (2017) assume that risk-taking propensities vary in individuals with different settings, for example, a small business owner may be a higher risk-taker than a corporate manager. Their study found that risk-taking propensity positively influences social entrepreneurial intentions. Therefore, we propose the following:

-

P29: Openness trait of personality will be directly related to perceived network

-

P30: Openness trait of personality will be directly related to ATB-SE

-

P31: Openness trait of personality will be directly related to SN-SE

Control variables

Based on the literature review, the demographic variables like age, gender, and education can be regarded as control variables in this model. However, in reality, the classification of these variables as control or independent will be governed by the nature of the study. For example, a researcher may want to study the interplay between gender and other variables and the effect of that relationship on social entrepreneurial intention formation. Thus, in that case, gender shall be treated as an independent variable.

Results and discussion

The motive of the present study was to identify the vital factors responsible for social entrepreneurial intention formation and then proposing a conceptual model based on the findings. A thorough literature review was conducted to arrive at a list of factors, which was further screened with the help of Pareto analysis.

Results of Pareto analysis

Figure 1 presents the result of the Pareto analysis in the form of a Pareto chart. The intersection of ~ 80% (79.62%) between the two axes occurs for the variable “perceived feasibility.” Hence, variables starting from “personality” till “perceived feasibility” have been taken as vital few factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions. The results of Pareto analysis further revealed that personality is the most important factor that forms intentions in a person to become a social entrepreneur, followed by attitude towards behavior, subjective norms, social capital, human capital, perceived behavior control, self-efficacy, perceived desirability, and perceived feasibility.

The choice of TPB as a theoretical framework and equivalencies of perceived desirability to attitude towards behavior and subjective norms and perceived feasibility and self-efficacy to perceived behavior control, as already discussed earlier, results in the elimination of perceived desirability, perceived feasibility, and self-efficacy from the list of vital few factors of Pareto analysis. Thus, we are left with six vital factors that affect social entrepreneurial intention formation.

The resulting model of social entrepreneurial intention formation

The resulting model of social entrepreneurial intention formation consists of social entrepreneurial intention as the dependent variable. There are six independent variables (constructs) in the model out of which three variables further consist of sub-constructs. Finally, as mentioned earlier, three factors namely age, gender, and education are control variables in the model. Table 4 describes the constitution of the model.

Conclusion

As social entrepreneurial intentions research is still in its nascent stage, this paper adds new insights to the literature by providing a holistic conceptual model of factors influencing and/or giving rise to intentions to become a social entrepreneur. This is one of the first studies on factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions to have used Pareto analysis technique after a thorough review of the existing literature. As the field of social entrepreneurship is on the rise, a large number of authors have conducted research on the factors influencing social entrepreneurial intentions, which resulted in a list containing large number of variables. There was a need to generalize a collective set of factors that form a universal model. In this light, Pareto analysis facilitated the screening of factors applying the 80:20 rule. The use of Pareto analysis also validates the claim that TPB is the most widely used theoretical framework in intention studies in social entrepreneurship till date.

This study provides a broader framework consisting of factors that pertain to the success of a prospective social entrepreneur. The model provides an understanding of a wide variety of factors and their interplay influencing social entrepreneurial intentions. This suggested interplay would help actors involved in grooming individuals who choose social entrepreneurship as a career option. One aspect also involves aid in designing the curriculum of trainings and courses in social entrepreneurship.

While this paper is expected to enhance the existing literature on the subject substantially, this is just a conceptual model. There is a scope to test this model empirically by translating propositions into hypotheses. As the independent variables of the model have been identified through extensive literature review, established and tested scales exist for all of them and also for the dependent variable (SEI) in the extant literature. These scales can be used in the same form or may be adapted to suit the needs of the researchers. The hypotheses of the study can then be tested by using multivariate statistical analysis technique like structural equation modeling (SEM). The SEM technique will help in analyzing the structural relationships between measured variables and latent constructs.

Abbreviations

- ATB:

-

Attitude towards behavior

- ATB-SE:

-

Attitude towards becoming a social entrepreneur

- HC-SE:

-

Social entrepreneurial human capital

- PBC:

-

Perceived behavioral control

- PBC-SE:

-

Perceived behavior control towards becoming a social entrepreneur

- SC-SE:

-

Social entrepreneurial social capital

- SEI:

-

Social entrepreneurial intentions

- SN:

-

Subjective norms

- SN-SE:

-

Subjective norms on becoming a social entrepreneur

- TPB:

-

Theory of planned behavior

References

Ab Talib, M. S., Abdul Hamid, A. B., & Thoo, A. C. (2015). Critical success factors of supply chain management: A literature survey and Pareto analysis. EuroMed Journal of Business, 10(2), 234–263.

Ajzen, I. (1987). Attitudes, traits, and actions: Dispositional prediction of behavior in personality and social psychology. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 20, pp. 1–63). Academic Press.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior.

Alvord, S. H., Brown, L. D., & Letts, C. W. (2004). Social entrepreneurship and societal transformation an exploratory study. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 40(3), 260–282.

Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei-Skillern, J. (2006). Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 1–22.

Ayob, N., Yap, C. S., Sapuan, D. A., & Rashidd, Z. A. (2013). Social entrepreneurial intention among business undergraduates: An emerging economy perspective. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 15(February 2016), 249–267. https://doi.org/10.22146/gamaijb.5470.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: US: Prentice-Hall, Inc..

Bargsted, M., Picon, M., Salazar, A., & Rojas, Y. (2013). Psychosocial characterization of social entrepreneurs: A comparative study. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, (4), 331–346.

Bateman, T. S., & Crant, J. M. (1993). The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14, 103–118.

Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442–453.

Bosch, D. A. (2013). A comparison of commercial and social entrepreneurial intent: The impact of personal values. Regent University.

Braga, J. C., Proença, T., & Ferreira, M. R. (2014). Motivations for social entrepreneurship – Evidences from Portugal. Tékhne, 12(2014), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tekhne.2015.01.002.

Burger, J. M. (2006). Personality (İD Erguvan Trans.). İstanbul: Kaknus Yayinlari.

Canadian Centre for Social Entrepreneurship. (2001). Social Entrepreneurship Discussion Paper. No. 1.Canadian Centre for Social Entrepreneurship, Edmonton.

Cavazos-Arroyo, J., Puente-Díaz, R., & Agarwal, N. (2017). An examination of certain antecedents of social entrepreneurial intentions among Mexico residents. Review of Business Management, 19(64), 180–199.

Cervone, H. F. (2009). Applied digital library project management: Using Pareto analysis to determine task importance rankings. OCLC Systems & Services: International digital library perspectives, 25(2), 76–81.

Chaucin, B., Hermand, D., & Mullet, E. (2007). Risk Perception and Personality Facets. Risk Analysis, 27(1), 171–185.

Chaudary, S., & Fatima, N. (2014, September). The Impact of Big Five Personality Traits, Leadership and Risk taking Ability on Social Entrepreneurial Dimensions. In Third Asian Business Research Conference (p. 29).

Chinchilla, A., & Garcia, M. (2017). Social entrepreneurship intention: Mindfulness towards a duality of objectives. Humanistic Management Journal, 1(2), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41463-016-0013-3.

Chipeta, E. M. (2015). Social entrepreneurship intentions among university students in Gauteng (Doctoral dissertation).

Chipeta, E. M., & Surujlal, J. (2017). Influence of attitude, risk taking propensity and proactive personality on social entrepreneurship intentions. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 15(2), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2017.15.2.03.

Chipeta, E. M., Surujlal, J., & Koloba, H. A. (2016). Influence of gender and age on social entrepreneurship intentions among university students in Gauteng province. South Africa. Gender and Behaviour, 14(1), 6885–6899.

Ciavarella, M. A., Buchholtz, A. K., Riordan, C. M., Gatewood, R. D., & Stokes, G. S. (2004). The Big Five and venture survival: Is there a linkage? Journal of Business Venturing, 19(4), 465–483.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology, 94(Supplement, 95–120.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). The five-factor model of personality and its relevance to personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 6(4), 343–359.

Crant, J. M. (1996). The Proactive Personality Scale as a Predictor of Entrepreneurial Intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 34(1), 42–49.

Dees, J. G. (1998). The meaning of social entrepreneurship.

Dees, J. G. (2001). The meanings of ‘social entrepreneurship. CA: Working paper. Stanford University. Stanford.

D'Orazio, P., Tonelli, M., & Monaco, E. (November 2013). (2013). Social and traditional entrepreneurial intention: what is the difference? In RENT XXVII: Research in Entrepreneurship and Small Business, Vilnius, Lithuania, 20 – 22.

Ernst, K. (2011). Heart over mind – An empirical analysis of social entrepreneurial intention formation on the basis of the theory of planned behavior. 1–309. Retrieved from http://nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn=urn:nbn:de:hbz:468-20120327-142543-6.

Fini, R., Grimaldi, R., Marzocchi, G. L., & Sobrero, M. (2009). The foundation of entrepreneurial intention. In Summer conference (pp. 17–19).

Fitch, J. L., & Ravlin, E. C. (2005). Willpower and perceived behavioral control: Influences on the intention-behavior relationship and post behavior attributions. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 33(2), 105–124. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2005.33.2.105.

Fotopoulos, C., Kafetzopoulos, D., & Gotzamani, K. (2011). Critical factors for effective implementation of the HACCP system: A Pareto analysis. British Food Journal, 113(5), 578–597.

Hayek, M., Williams, W. A., Randolph-Seng, B., Pane-Haden, S. (2013). Towards a model of social entrepreneurial intentions: Evidence from the case of Daisy Low. In Academy of Management Proceedings (2013, 1, 11645). Academy of Management.

Hockerts, K. (2017). Determinants of social entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 41(1), 105–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12171.

Hockerts, K. N. (2013). Antecedents of social entrepreneurial intentions: A validation study. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2013(1), 16805. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2013.16805abstract.

Ip, C. Y., Wu, S. C., Liu, H. C., & Liang, C. (2017). Revisiting the antecedents of social entrepreneurial intentions in Hong Kong. International Journal of Educational Psychology, 6(3), 301–323.

Ip, C. Y., Wu, S.-C., Liu, H.-C., & Liang, C. (2018). Social entrepreneurial intentions of students from Hong Kong. Journal of Entrepreneurship.

İrengün, O., & Arıkboğa, Ş. (2015). The effect of personality traits on social entrepreneurship intentions: A field research. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 1186–1195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.172.

Jensen, T. L. (2014). A holistic person perspective in measuring entrepreneurship education impact—Social entrepreneurship education at the humanities. International Journal of Management Education, 12(3), 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2014.07.002.

Jilenga, M. T. (2017). Social enterprise and economic growth: A theoretical approach and policy recommendations. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 7(1), 41–49.

Karuppusami, G., & Gandhinathan, R. (2006). Pareto analysis of critical success factors of total quality management: A literature review and analysis. The TQM Magazine, 18(4), 372–385.

Kedmenec, I., Rebernik, M., & Peric, J. (2015). The impact of individual characteristics on intentions to pursue social entrepreneurship. Economic Review, 66(2), 119–137 Retrieved from http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=205475&lang=en.

Krueger, N. F., Jr., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5–6), 411–432.

Krueger, N. F. (2003). The cognitive psychology of entrepreneurship. In Handbook of entrepreneurship research (pp. 105–140). Boston: Springer.

Krueger, N. F., & Deborah Brazeal, J. V. (1994). Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 91–104. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1505244.

Lee, S. H., & Wong, P. K. (2004). An exploratory study of technopreneurial intentions: A career anchor perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(1), 7–28.

Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617.

Liñán, F., & Javier Santos, F. (2007). Does social capital affect entrepreneurial intentions? International Advances in Economic Research, 13(4), 443–453.

Liu, H. C., Ip, C. Y., & Liang, C. (2017). Demographic analysis for the social entrepreneurial intentions of media workers. In International Conference on Business and Information (BAI2017), International Business Academics Consortium, Hiroshima, Japan.

Liu, H. C., Ip, C. Y., & Liang, C. (2018). A new runway for journalists: On the intentions of journalists to start social enterprises. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation.

Llewellyn, D. J., & Wilson, K. M. (2003). The controversial role of personality traits in entrepreneurial psychology. Education+ Training, 45(6), 341–345.

Locke, E. A. (2000). Motivation, cognition, and action: an analysis of studies of task goals and knowledge. Applied Psychology, 49(3), 408–429.

Loku, A., Gogiqi, F., & Qehaja, V. (2018). Social enterprises like the right step for economic development for Kosovo. European Journal of Marketing and Economics, 1(1), 26–31.

Lombard, A., & Strydom, R. (2011). Community Development Through Social Entrepreneurship. The Social Work Practitioner-Researcher, 23(3), 327–344.

Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 36–44.

Mair, J., & Noboa, E. (2005). How intentions to create a social venture are formed: A case study. SSRN Electronic Journal, 3(593), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.875589.

Mair, J., & Noboa, E. (2006). Social entrepreneurship: How intentions to create a social venture are formed. In Social entrepreneurship (pp. 121–135). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Miller, T. L., Grimes, M. G., McMullen, J. S., & Vogus, T. J. (2012). Venturing for others with heart and head: How compassion encourages social entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review, 37(4), 616–640.

Mitchel, J. O. (1981). The effect of intentions, tenure, personal, and organizational variables on managerial turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 24(4), 742–751.

Moorthy, R., & Annamalah, S. (2014). Consumers’ perceptions towards motivational intentions of social entrepreneurs in Malaysia. Integrative Business and Economics Research, 3(1), 257–287 Retrieved from http://sibresearch.org/uploads/2/7/9/9/2799227/riber_k14-140_257-287.pdf.

Mount, M. K., Barrick, M. R., Scullen, S. M., & Rounds, J. (2005). Higher-order dimensions of the big five personality traits and the big six vocational interest types. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 447–478.

Nga, J. K. H., & Shamuganathan, G. (2010). The influence of personality traits and demographic factors on social entrepreneurship start up intentions. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(2), 259–282.

Ong, J. W., & Ismail, H. (2008). Revisiting Personality Traits in Entrepreneurship Study From a Resource Based Perspective. Business Renaissance Quarterly, 3(1), 97–114.

Politis, K., Ketikidis, P., Diamantidis, A. D., & Lazuras, L. (2016). An investigation of social entrepreneurial intentions formation among South-East European postgraduate students. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 23(4), 1120–1141.

Prabhu, V. P., Mcguire, S. J. J., Kwong, K. K., Zhang, Y., Ilyinsky, A., & Wagner Graduate, R. F. (2016). Social entrepreneurship among millennials: A three-country comparative study. Australian Academy of Accounting and Finance Review, 2(4).

Prieto, L. (2010). Influence of proactive personality on social entrepreneurial intentions among African American and Hispanic undergraduate students: The moderating role of hope. Dissertation, (August).

Prieto, L. C., Phipps, S. T. A., & Friedrich, T. L. (2012). Social entrepreneur development: An integration of critical pedagogy, the theory of planned behavior and the ACS model. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 18(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/17506200710779521.

Rapando, V. O. A. (2016). Factors influencing social entrepreneurship in Kariobangi, Kenya (Doctoral dissertation, United States International University-Africa).

Ryzin, G. G., Grossman, S., DiPadova-Stocks, L., & Bergrud, E. (2009). Portrait of the social entrepreneur: Statistical evidence from a US panel. Voluntas, 20(2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-009-9081-4.

Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). Some social dimensions of entrepreneurship in C. Kent, D. Sexton and K. Vesper (eds) The encyclopedia of entrepreneurship Englewood Cliffs.

Singh, G., & DeNoble, A. (2003). Early retirees as the next generation of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(3), 207–226.

Sullivan Mort, G., Weerawardena, J., & Carnegie, K. (2002). Social entrepreneurship: Towards conceptualization and measurement. In 2002 AMA Summer Marketing educators conference (Vol. 13, pp. 5–5). American Marketing Association.

Talib, F., Rahman, Z., & Qureshi, M. N. (2010). Pareto analysis of total quality management factors critical to success for service industries. International Journal of Quality Research (IJQR), Center for Quality, University of Podgorica Montenegro and University of Kragujevac, Serbia, 4.

Thompson, E. R. (2009). Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 33(3), 669–694.

Tiwari, P., Bhat, A. K., & Tikoria, J. (2017). An empirical analysis of the factors affecting social entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 7(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-017-0067-1.

Tran, A. T. P., & Von Korflesch, H. (2016). A conceptual model of social entrepreneurial intention based on the social cognitive career theory. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10(1), 17–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-12-2016-007.

Tubbs, M. E., & Ekeberg, S. E. (1991). The role of intentions in work motivation: Implications for goal-setting theory and research. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 180–199.

Yang, R., Meyskens, M., Zheng, C., & Hu, L. (2015). Social entrepreneurial intentions. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 16(4), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.5367/ijei.2015.0199.

Yiu, D. W., Wan, W. P., Ng, F. W., Chen, X., & Su, J. (2014). Sentimental drivers of social entrepreneurship: A study of China’s Guangcai (Glorious) Program. Management and Organization Review, 10(1), 55–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/more.12043.

Zahra, S. A., Rawhouser, H. N., Bhawe, N., Neubaum, D. O., & Hayton, J. C. (2008). Globalization of social entrepreneurship opportunities. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 2(2), 117–131.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

No funding was provided for the study.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VA is the lead author of the study. The work in this paper is a part of his ongoing doctoral work in the field of social entrepreneurial intentions. AA and OPW provided the guidelines for this research and also made corrections in the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahuja, V., Akhtar, A. & Wali, O.P. Development of a comprehensive model of social entrepreneurial intention formation using a quality tool. J Glob Entrepr Res 9, 41 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0164-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0164-4