Abstract

The role of entrepreneurship in economic development is increasingly recognized by policymakers and researchers. Entrepreneurship has been advanced as the panacea for youth unemployment and wealth creation. However, studies on the determinants of entrepreneurial intentions have been inconclusive. Building on the push-pull-mooring model from the migration literature as a theoretical framework, this study provides an integrative model for predicting entrepreneurial intentions amongst young graduates. The survey data was drawn from a sample of 288 National Youth Service Corp members (NYSC) in Anambra State, Southeast Nigeria, to test the applicability of the model. The model was tested using Hierarchical regression. The result confirms the predictive ability of the PPM model on entrepreneurial intentions. Specifically, the result reveals that the pull factors (i.e, independence, autonomy, opportunities exploitation e.t.c) and the mooring variables (i.e., government support, personal attitude, self-efficacy e.t.c) significantly influence entrepreneurial intentions with the mooring variables having the most influence. Therefore, the study recommends the need for policy initiatives towards exposing these young graduates to market opportunities through a mentor-protégé arrangement with successful entrepreneurs during the NYSC programme and providing the necessary supports in the form of funding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The rise of youth unemployment and the slow pace of economic growth have attracted the attention of researchers and policymakers towards developing policies that will foster the spirit of entrepreneurship and facilitate new venture creation (Giacomin et al. 2011), especially among young people. This is particularly due to the contributions of entrepreneurship in job creation and economic growth (Uhlaner and Thurik, 2007). Thus, understanding the motivation for entrepreneurial behavior is increasingly recognized (Segal et al. 2005). Entrepreneurial behavior is precipitated on intentions to conduct such behavior (Krueger et al. 2000). In other words, intentions are the best predictors of behavior (Ajzen, 2002). However, there is no consensus on the theoretical explanations for entrepreneurial intentions (EI; Solesvik 2013).

Entrepreneurship refers to any attempt at creating new business or venture such as self-employment, a new business organization or the expansion of existing business by an individual, group of individuals or established businesses (Reynolds et al., 2001). Entrepreneurship involves a complex and dynamic activity that requires cognitive processes such that individuals are able to think about future outcomes and determine the desirability and feasibility of such outcomes (Hisrich et al. 2005; Segal et al. 2005). Thus, individual idiosyncrasies exist in their rationale and social characteristics for new business creation such that what may be an opportunity for one might be a necessity to another (Giacomin et al. 2010). Furthermore, since the decision to form a new venture is conscious and pre-meditated, intention-based studies of entrepreneurship behavior provide a robust basis for understanding predictors of entrepreneurship behavior (Ajzen 1991; Franke and Lüthje 2004). Davidsson (1995) add that studying entrepreneurial intentions avoid the biases that may occur from individual and situational factors that develop as a result of running an enterprise.

Previous studies have examined the determinants of entrepreneurial intentions from the perspectives of necessity/opportunity driven or push/pull dichotomy (Jamali 2009; Ismail et al. 2012; Giacomin et al. 2011; Caliendo and Kritikos 2009), triggers and barriers (Fatoki and Patswawairi 2012; Giacomin et al. 2010) personality traits (Canedo et al. 2014) theory of planned behaviour (Iakovleva et al. 2011) and Shapero’s entrepreneurial event theory (Solesvik et al. 2012; Krueger et al. 2000). Additionally, attempts to develop an integrative framework for understanding determinants for entrepreneurial behavior is limited (Solesvik 2013; Liñán and Chen 2006; Segal et al. 2005; Fitzsimmons and Douglas 2005). However, such models are at best atheoretical or fragmented. More so, in spite of the plethora of studies examining entrepreneurial intentions, the results have been mostly mixed and inconclusive (Segal et al. 2005).

Drawing on the push-pull-mooring (PPM) model from the migration literature (Bansal et al. 2005; Moon 1995), this paper attempts to investigate the predictive factors of entrepreneurial intentions using young graduates in Nigeria. Specifically, this study seeks to examine the effects of push, pull and mooring factors on entrepreneurial intentions. The study argues that an understanding of the necessity-driven push factors (e.g., uncertainty of employment, dissatisfaction with life and democracy, poor academics grade, social recognition) or opportunity driven pull factors (e.g., market opportunity, independence and profit search) with the knowledge of the mooring variables (e.g., personal attitude, self-efficacy, social norms, risk tolerance, government support and finance) might provide important information about entrepreneurship intentions.

Review of related literature

The push-pull-mooring factors and entrepreneurship intentions have rarely been studied. As noted earlier, most of the previous studies in the entrepreneurship intention literature examined the push and pull factors, necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs, triggers of entrepreneurship intentions and personality factors.

In studies examining the push and pull factors, Giacomin et al. (2007) examined individual’s entrepreneurship orientation from the perspective of push-pull dynamics and find that younger people were motivated by both push factors – desire for independence and pull factor- profit objective and social status, whereas old unemployed people are guided solely by the lack of an employment. In addition, the authors find that non-unemployed old people become entrepreneurs out of ‘hobby’. Fatoki and Patswawairi (2012) investigate the factors that motivate or hinder immigrant-entrepreneurs to pursue entrepreneurship from a sample of 101 African immigrants in South Africa and found that immigrant entrepreneurs were driven into entrepreneurship by both push and pull factors with unemployment being the most important push factor. The authors add that the obstacles to the performance of immigrant-owned businesses include finance, weak markets, human capital and lack of support.

In another stream of studies investigating, the psychological and personal factors, Douglas and Shepherd (2002) examined the relationship between career choice and peoples’ attitudes toward income, independence, risk, and work effort among a sample of 94 alumni of an Australian university using conjoint analysis and found that people with a positive attitude towards risk and independence demonstrate a strong intention to be self-employed whereas the desire to be rich is not a significant predictor of EI. Segal et al. (2005) In a related study, on the motivation to become an entrepreneur among a sample of 114 undergraduate business students from a Florida University, found tolerance for risk, perceived feasibility, and net desirability to significantly influence entrepreneurial intentions. Ozaralli and Rivenburgh (2016), comparing the antecedents of entrepreneurship intention among 589 Junior and Senior US and Turkey students, found that both U.S and Turkey students demonstrate a low level of EI. U.S students were found to be risk averse towards entrepreneurship while Turkish students find economic and political conditions to be unfavorable for start-ups. In addition, they find a statistically significant relationship between personality attributes of optimism, innovativeness, risk-taking propensity and entrepreneurial intention.

In an attempt to Integrate the factors that determines entrepreneurship intentions, Iakovleva and Kolvereid (2009), attempted to integrate the TPB and SEE model into an integrative model using data from 324 Russians University business students. In a series of test including hierarchical regression analysis, the authors find that the intention to become self-employed and start one’s own business is indirectly influenced by attitude, subjective norm and, perceived behavioral control through the desirability-feasibility construct. Solesvik et al. (2012) in a similar integrative study involving themes from SEE and TPB, structural equation modeling and found that those with a higher level of perceived desirability, perceived feasibility, positive attitude toward the entrepreneurship and perceived behavioral control were more likely to report the formation of entrepreneurial intentions.

Entrepreneurial intentions

Typically, individuals have to choose between unemployment, self-employment, and employment (Knight, 1921 cited in Verheul et al. 2010). Entrepreneurial intention connotes an individual decision to move from unemployment or salaried employment to self-employment. The decision to be self-employed is considered voluntary, conscious and intentionally planned (Krueger et al. 2000). According to Linan et al. (2013), entrepreneurial intentions (EI) is defined as a conscious awareness and conviction by an individual with the intent to set up a new business venture and plans to do so in the future. It refers to intentions to be self-employed or to start-up a business (Iakovleva and Kolvereid 2009). For entrepreneurial intentions to eventuate, the motivation to pursue entrepreneurship, a perception of an ostensible entrepreneurial opportunity or the necessity to behave entrepreneurially and access to the means to become self-employed must be present (Fitzsimmons and Douglas 2005).

Previous studies examined entrepreneurial intentions based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 2002) and the Entrepreneurial Event Theory (SEE; Shapero 1982). However, the factors that constrain or inspire entrepreneurial activity are rarely studied (Brännback et al. 2007). Though, TPB accounts for the personal and social factors that predict EI (Iakovleva et al. 2011), however, the TPB model does not deal with the possibility of intentions being obstructed by impediments that can be potentially controllable or uncontrollable (Brännback et al. 2007).

Theoretical background

Entrepreneurship researchers have attempted to capture the antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions by adapting the Ajzen (1991) Theory of Planned Behaviour (Solesvik 2013; Krueger et al. 2000; Liñán and Chen 2006), Shapero (1982) entrepreneurial event theory (Krueger et al. 2000; Solesvik et al. 2012), or from the push or pull dichotomy (Verheul et al. 2010; Giacomin et al. 2011; Caliendo and Kritikos 2009). Till date, there are no agreed theories to explain EI (Solesvik 2013). Accordingly, researchers call for frameworks grounded in well-established theories (Segal et al. 2005) to investigate EI. This study fills this void by proposing an integrative framework based on the push-pull-mooring model and the theory of planned behavior.

Push pull mooring migration model

In sociology and human geography, migration involves “the movement of a person (migrant) between two places for a certain period of time” (Jackson 1986). According to the PPM model, migrants’ decision to move from one geographical location to another is influenced by a push, pull and mooring factors (Bansal et al. 2005; Fu 2011). Push factors represent expulsive factors at the origin that provides a reason to leave, such as poverty, unemployment, low social status, political repression, rapid population growth, poor marriage prospects, lack of opportunity for personal development, natural disaster and landlessness (King 2012; Bansal et al. 2005). The pull factors represent attraction at the destination that pulls people towards them (Fu, 2011). King (2012) add that pull factors include better income, job prospect, better education, welfare system, good environment and living conditions and, political freedom. Push factors are typically examined as negative factors at the origin while pull factors are examined as positive factors at the destination (Bansal et al. 2005). The mooring variables represent personal, social factors or cultural variables that either facilitate or inhibit the decision to move (Fu, 2011). The mooring variable accounts for the complexity of migration decisions capable of holding potential migrants back or facilitating their movement to their desired destination (Moon 1995). Mooring variables include cost, cultural barriers, political obstacle, life stage and personality (King 2012).

The push-pull-mooring model has been applied with strong predictive power in consumer switching literature (Bansal et al. 2005), career commitment (Fu 2011) and online games (Hou et al. 2009).

Theory of planned behavior

Entrepreneurship researchers have demonstrated the robustness of Ajzen's (1991) Theory of Planned Behavior in explaining entrepreneurial intentions (Kolvereid, 1996; Krueger et al. 2000; Liñán and Chen 2009). According to TPB, broad attitudes and personality trait have an indirect effect on behavior by influencing intentions (Solesvik 2013). Intentions are based on three antecedents; attitude towards the behavior, social norm, and perceived behavioral control. Attitude towards behaviour refers to the degree of positive or negative evaluation of performing a behaviour, social norm relates to social pressure from significant others such as family, friends, and other individuals who would approve or disapprove of one’s behaviour (Liñán and Chen 2006), perceived behavioural control reflects the relative ease or difficulty of performing a behaviour and is akin to self-efficacy. Krueger et al. (2000), posit that TPB shares similarities with Shapero’s Entrepreneurial Event theory (SEE), According to Krueger et al. (2000), perceived desirability in SEE corresponds with both attitude and subjective norm constructs of TPB. Also, SEE’s perceived feasibility overlaps with perceived behavioral control in TPB and are both conceptually associated with self-efficacy (Bandura 1997). However, entrepreneurial intentions involve an individual readiness to behave entrepreneurially when the means and the opportunity or necessity to do so exists simultaneously (Fitzsimmons and Douglas 2005). Accordingly, the push and pull dynamics need to be considered as triggers to entrepreneurial intentions (Buenstorf 2009).

Research model and hypotheses

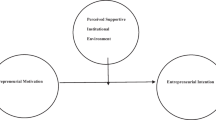

This study proposes an integrative framework based on the push-pull-mooring (PPM) model by converging theoretical concepts from the push-pull theory and Theory of Planned Behaviour. The TPB behavior identifies personal, social and cultural factors that served as the mooring variables in the PPM model.

The push-pull- model (PPM) and entrepreneurial intentions

The push-pull theory has been in the entrepreneurship research domain since the seminal work of Gilad and Levine (1986). The push-pull theory of entrepreneurship shares some semblance with the push-pull-mooring model of human migration. Giacomin et al. (2007) corroborating this analogy posit that “... creation of new firms subtends the movement of individuals in salaried employment or unemployment towards self-employment [emphasis added]” (p.4). Thus, entrepreneurship can be conceptualized as an individual’s intention to move or migrate from unemployment or salaried-employment to self-employment. Following the push-pull-mooring model of the migration literature, the intent to pursue an entrepreneurial career path is influenced by negative factors such as dissatisfaction with a current job, life or one’s current state, the difficulty of finding employment, difficult economic conditions, social recognition, or inflexible work schedule which moves individuals into self-employment (Segal et al. 2005). These negative factors are regarded as the push factors at an individual’s current state analogous to his or her origin. The push effect occurs when conflicts exist between an individual actual state and the ideal state forcing him/her into self-employment (Uhlaner and Thurik 2007). Push effects are associated with some levels of dissatisfaction with an individual current situation in life (Thurik and Dejardin 2012; Noorderhaven et al. 2004) and have been found to motivate entrepreneurship behavior (Giacomin et al. 2011). Push theory shares a number of conceptual similarities with some construct of the push factors from migration literature.

On the other hand, the pull theory refers to attractions at the destination which move individuals into self-employment or entrepreneurship by seeking independence, wealth, and self-fulfillment (Gilad and Levine 1986). “The pull factors are those where an individual is attracted primarily by the prospect of founding a business” (Ritsilä & Tervo, 2002, p.2). Migration literature defines the pull factors as attractions at the destination that moves migrants towards them (Moon 1995). The ‘destination’ is entrepreneurship. The fortuitous circumstances perceived to be present in becoming entrepreneurs would spur the intent to become self-employed. Pull factors has been found to impact on entrepreneurial motivation (Giacomin et al. 2011; Ismail et al. 2012). Pull variables identified in the entrepreneurship literature includes independence, profit search, and market opportunity (Giacomin et al. 2011; Caliendo and Kritikos 2009).

Notwithstanding the push or pull factors towards entrepreneurship, certain factors make entrepreneurship desirable (e.g., cultural and social norms) and feasible (e.g., availability of skills) (Hisrich et al. 2005; Segal et al. 2005). These personal, social or cultural factors account for variation in entrepreneurship perceptions (Giacomin et al. 2011). Furthermore, the complexity of entrepreneurial decision cannot be fully captured by the simplicity of the push and pull theory (Verheul et al. 2010). Hence the push or pull entrepreneur differ with respect to factors that facilitate or mitigate the decision to behave entrepreneurially (Verheul et al. 2010; Bansal et al. 2005). These factors that ‘facilitates or hinders’ conceptually corresponds to the mooring variables in the PPM migration model. Mooring variables relate to personal, social or cultural factors that can either hold potential migrants to their original destination or facilitate migration to a new destination (Fu 2011; Bansal et al. 2005). Mooring variables include obstacles such as family attachment, personal anxiety, and cost of moving (Bansal et al. 2005). From the entrepreneurial perspective, mooring variables have been implicitly examined. For instance, Krueger et al. (2000) argue that a strong intention to start a business might suffer a long delay due to immediate circumstances such as marriage, childbearing, finishing school, a lucrative or rewarding job or earthquake. In addition, Luthje and Franke (2003) argue that entrepreneurial intentions are shaped by an individual perception of barriers as well as support to start-up. Thus, mooring variables in the context of entrepreneurship will include personal attitude, subjective norm, self-efficacy, risk tolerance, finance and government support.

In other words, the factors that influence an individual into pursuing an entrepreneurial career path is analogous to what influences people to migrate from one destination to another in the migration literature. Next, a detailed discussion on the push, pull and mooring factors are presented.

The push factors

The push factors include dissatisfaction, unemployment and social recognition. Unemployment is a principal factor in the migration literature. Most migrants move due to un(der)employment. In entrepreneurship research domain, unemployment impacts new firm formation. Unemployed individuals are pushed into self-employment when they are faced with choosing between unemployment and self-employment (Ritsilä and Tervo 2002). Unemployment has been found to have a positive and a negative impact on entrepreneurship (Thurik et al. 2008).

According to Bansal et al., (2005) Dissatisfaction with factors at the origin is emphasized in the migration literature as reasons for migration. Accordingly, from an entrepreneurship perspective, dissatisfaction has been confirmed as a motive for self-employment (Huisman and De Ridder, 1984). Arguing from a macro perspective, Thurik and Dejarin (2012), suggest that an individual may consider self-employment when his/her personal values and belief differs from that of the society; especially when such society is culturally non-supportive of entrepreneurship. Previous research has examined dissatisfaction with previous work, dissatisfaction with life, dissatisfaction with democracy and found a strong correlation with self-employment (Brockhaus 1980; Noorderhaven et al. 2004). Sarasvathy (2004) add that those who are unemployable for lack of education or poor academic performance may be pushed into self-employment.

King (2012) identified social recognition or low social status as a push factor in migration studies. In the context of entrepreneurship, Giacomin et al. (2011) classified social recognition as a push factor. Following social legitimation argument, Individuals with low social status will be pushed into entrepreneurship to obtain prestige or become socially recognized especially when a culture supports entrepreneurship (Thurik and Dejardin 2012). Singh et al. (2011) found a significant relationship between the desire for social recognition and entrepreneurship amongst female entrepreneurs in Nigeria. Similarly, Giacomin et al. (2011) found young people to be pushed into entrepreneurship by the search for social recognition.

The pull factors

The pull factors are usually considered in the light of the desire to become independent, a motivation to search for profit or wealth and, the perception of a market opportunity.

The desire for Independence is predominantly a motive for self-employment (Verheul et al. 2010; Van Gelderen and Jansen 2006). Independence in the context of entrepreneurship refers to a willingness to be free from external control in decision making and typically represented by the desire for autonomy, having no boss and creating one’s own job (Giacomin et al. 2011; Caliendo and Kritikos 2009). Independence describes an individual desire for freedom, control, and flexibility (Zellweger et al. 2011). Independence is analogous to political freedom from the migration literature (King 2012) though, from a macro-perspective. Therefore, the desire to be independent as perceived in entrepreneurship is an attraction towards pursuing an entrepreneurial career path. Previous studies have found the desire for independence to be positively related to entrepreneurial intentions (Douglas and Shepherd 2002; Fitzsimmons and Douglas 2005).

Profit search relates to rent-seeking tendencies of individuals. Extant literature has demonstrated the pursuit of profit in terms of earning big money, increasing income, building equity or personal wealth as antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions with inconsistent results (Singh et al. 2011; Giacomin et al. 2010; Giacomin et al. 2007). People would typically desire to become entrepreneurs to increase their income and financially independent. Migration literature also emphasizes the pursuit of better income as an attraction for migrants (King 2012; Bansal et al. 2005). Fitzsimmons and Douglas (2005) report that individuals with stronger positive attitudes toward income exhibit higher entrepreneurial intentions.

The perception of market opportunities is a critical part of entrepreneurship such that an entrepreneur searches for new or better solutions than those given in the actual market environment (Lee et al. 2005; Buenstorf 2009). It is the existence of opportunities in a market that act as an incentive at the destination – entrepreneurship – which attracts people into seeking self-employment. However, the ability to identify these opportunities are related to human capital (i.e, education or previous experience). Gatewood et al. (1995) found the identification of market opportunities as the reason offered most for start-ups.

Mooring factors

Personal attitude depends on the perception of the outcome resulting from a target behavior (Brännback et al. 2007) such that if possible outcomes are expected, favorable attitudes are developed. Thus, attitude predicts behavior through intentions (Krueger and Carsud, 1993). The significant effect of attitude towards entrepreneurship on entrepreneurial intentions is well documented (Solesvik et al. 2012; Franke and Lüthje 2004; Krueger et al. 2000).

Bansal et al. (2005), emphasizes the central role of significant others in facilitating or mitigating behavioral intentions. Subjective norm measures an individuals’ perception of important people in their lives and in some cases with their motives to comply. Branback et al. (Brännback et al. 2007) add that subjective norm provides a guideline for culturally desirable behaviors. Therefore, entrepreneurship decision is embedded in the subjective norm. A number of studies reported a significant relationship between subjective norm and entrepreneurial intentions (Liñán and Chen 2009; Ozaralli and Rivenburgh 2016).

Self-efficacy is concerned with the judgment of an individual’s capability to successfully execute behavior required to produce a certain outcome (Bandura 1998). Self-efficacy is related to task effort and performance, persistence, tenacity, resilience and emotional reactions in the face of failure (Bandura 1997, 1998). From the entrepreneurship perspective, entrepreneurial self-efficacy is the strength of a person’s belief in his/her capacity to successfully perform the roles and tasks of an entrepreneur (Chen et al. 1998). According to Lee et al. (2005), self-efficacious individuals are likely to perceive entrepreneurial environment positively and make the best out of the situation. In other words, high self-efficacy persons are likely to exercise control over entrepreneurial events, while a person low in self-efficacy may not be willing to exert extra effort in the face of obstacles and setbacks (Fu 2011). From the perspective of PPM, a person low in self-efficacy will not migrate, even when the push and pull forces are strong. Armitage and Conner (2001) concluded that self-efficacy is more strongly correlated with intention and behavior.

Risk tolerance refers to a tendency to take or avoid risks. Characteristically, risk tolerance is often associated with entrepreneurship (Ozaralli and Rivenburgh 2016). There is evidence to suggest that the more tolerant a person is to risk, the more likely that person will want to be self-employed (Douglas and Shepherd 2002; Franke and Lüthje 2004). A recent study found a negative correlation between risk tolerance and entrepreneurial intention for US and Turkey students (Ozaralli and Rivenburgh 2016).

Government support and availability of finance have been examined as environmental factors that facilitate or impede entrepreneurial intentions (Franke and Lüthje 2004). In developing countries, the presence of opportunities may be mitigated by an unconducive environment (Singh et al. 2011) that manifest as high-level bribery and corruption, restrictive entry regulations, significantly low-level of financial services and higher risk aversion by commercial banks (Georgios 2014). The perception of these contextual factors moderates the attitude-intention relationship (Franke and Lüthje 2004). These environmental factors have been found to have a negative impact on self-employment (Smallbone and Welter 2001). The conceptual model is shown in (Fig. 1) below.

In sum, much of the variables identified as push, pull or mooring variables that facilitates or impedes entrepreneurial intentions corresponds with the migration literature. Accordingly, the following is hypothesized:

-

H 1 : Push factors will have a strong and positive relationship with EI.

-

H 2 : Pull factors will have a strong and positive relationship with EI.

-

H 3 : Mooring variables will have a positive and significant influence on EI.

Method

Data for the study was obtained via survey. Survey data were collected from a random sample of National Youth Service Corp (NYSC) members in Anambra State, Southeast Nigeria. NYSC members are unique data set for this kind of study. They are groups of fresh young graduates from various universities and colleges of higher learning across the country, with diverse background posted for a mandatory One year National Service within a state in Nigeria. During the One year, young graduates undergo Para-military training and are afterward deployed to various establishments (including schools, multinational companies, private and public enterprise) to serve for a monthly allowance (allowee). The NYSC program enables its participants to acquire the spirit of self-reliance and encourage them to develop skills for self-employment independent from the training received from their respective schools. Therefore, an NYSC member is equipped to pursue a paid employment or an entrepreneurial career path. Following Kueger et al. (Krueger et al. 2000), our sample consists of subjects with diverse career intentions and attitude towards entrepreneurship.

Sample and procedure

Data to test the model and hypotheses were drawn from a random sample of 288 respondents from NYSC secretariats in Anambra State, Southeast Nigeria. Copies of the questionnaire were self-administered to the respondents using trained interviewers. The survey was completed anonymously during the NYSC members’ weekly Community Development Programme meeting in February/March 2016.

For the pre-test, data was collected from a convenience sample of 54 undergraduates in their final year enrolled in a Management course at a Federal University also in Southeast Nigeria. To assure content validity, senior academics in marketing and Entrepreneurship Department reviewed the items that were based on relevant previous studies. The questionnaire designed was then subsequently modified and before administering to respondents.

Measurement

All variables in the hypotheses were assessed with a multi-item scale. Multi-item scale covers a broad range of meanings to cover a construct; measures more response category and makes it easy to compute the internal consistency of a construct (Hoeppier et al. 2012). The constructs were measured using scales adapted from previous studies (e.g., Liñán and Chen 2009; Giacomin et al. 2011; Noorderhaven et al. 2004)

Dependent variable

Entrepreneurial intentions were set as the dependent variable. Six intentions based items adapted from Linen and Chen (2009) was used to measure entrepreneurial intentions. The items were measured on a five-point Likert-scale ranging from 5 strongly agree to 1 strongly disagree. The items were then loaded to test its reliability using Cronbach alpha.

Independent variables

The antecedents of entrepreneur intentions were measured using three independent variables: push, pull and mooring variables adapted from previous studies. The push factors which are circumstances that force an individual to establish a business are mostly related to employment e.g. lay off, job insecurity, job dissatisfaction, and unemployment. Accordingly, this study operationalized the push factors based on, unemployment, dissatisfaction with life, dissatisfaction with democracy, social recognition and poor academic grades (reverse coded). Measurement constructs were adapted from Giacomin et al. (2011), Noorderhaven et al. (2004) and self-developed for this study based on themes from the literature. The pull factors which are fortuitous circumstances that make entrepreneurship or self-employment attractive were operationalized as a market opportunity, autonomy, and profit search. The measurement constructs were adapted from Giacomin et al. (2011). Mooring factors are personal, social and cultural factors responsible for differences in individual reactions to various combination of pull and push factors. Much of the entrepreneurial intentions models have been examined based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen 1991) or Shapero’s Entrepreneurial Event Theory (Shapero, 1982). These models have been used to predict EI by accounting for personal, social and cultural factors that can lead to the creation of new firms (Iakovleva et al. 2011). Accordingly, mooring effect is operationalized as subjective norm, self-efficacy, and risk tolerance, attitude towards entrepreneurship, financial resources, and government support. All items are Likert-scale type ranging from 5 strongly agree to 1 strongly disagree.

Control variables. Four variables were included to account for the effect of individual characteristics on EI. They include sex (0-male, 1-female), age (in years), entrepreneurship education (1-yes, 0-No) and entrepreneurial parent (1-yes, 0-No).

Results

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis with varimax rotation and reliability analysis was performed to assess the validity and reliability of the measures. Factor loadings below 0.4 were set as benchmark and Cronbach alpha > 0.7. All 38 – items converge on 7 factors. Factor 1 consists of items initially measured as personal attitude and subjective norm variables converging into one and label perceived desirability (Krueger et al. 2000; Brännback et al. 2007). Factor 2 consists of availability of finance and government support variables, therefore, label environmental factors; factor 3 consists of dimensions measuring pull factors (i.e, profit search, independence and market opportunity) therefore labeled pull factors. Factor 4 is labeled self-efficacy; factor 5 labeled dissatisfaction and factor 6 label social recognition both pertaining to push factors. Finally, factor 7 is risk tolerance variables. Three items were excluded from the measures. The cumulative explained variance is 75%. Cronbach’s alpha for the dimensions was reliable. The summary of the factor analysis and reliability test is shown in Table 1 below.

Hypotheses testing

Multiple hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to test the hypotheses. Multiple regression analysis tests the causal relationship between dependent and independent variables by accounting for the difference in the predictive power of additional variables included in the model and enable a researcher to account for the effect of control variables. In the present study, the authors account for the effect of control variables in relation to the variables of interest. The confidence level is set at 95% (p < 0.05). Therefore, the null hypotheses are rejected if p < 0.05, otherwise the alternate hypotheses is accepted.

In model 1 (r2 = .06, p < .01), the effect of control variables on entrepreneurial intentions was examined. Only entrepreneurship education (β = 0.20, p < 0.05) had a positive and significant effect on entrepreneurial intentions and explains 6% of the variance in the dependent variable. Model 2 (r2 = 14, p < 0.05) incorporates the push-pull-mooring variable in addition to the control variables. The result shows that for the Pull factors the beta co-efficient equals .193, and p-value is less than 0.05, therefore, the null hypotheses is rejected and the alternate accepted. It is therefore, concluded that the pull factors significantly influence entrepreneurial intentions among young graduates; thus, supporting Hypothesis 2. Similarly, the p-value for the mooring variables (β = .231, p < .0.001) is less than 0.05. Therefore, the null hypothesis is rejected and the alternate accepted and conclude that the mooring variable significantly influences entrepreneurial intentions among young graduates. Thus, supporting Hypothesis 3. In addition, the mooring variables had the strongest impact on entrepreneurial intentions as indicated by the higher beta coefficient. However, for the push factor (β = .012, p > 0.05) the p-value is greater than 0.05, therefore the null is accepted and the alternate rejected. It can therefore be concluded that there is no significant effect of the push factor on entrepreneurial intentions. Thus, hypothesis 1 is not supported. Though model 2 explains 10% of the variation in entrepreneurial intentions, the overall model is a good fit and improves significantly from model 1 (F = 3.18, p < 0.05) (Table 2). The summary of the result is presented in Table 2.

A follow-up analysis was also conducted to test the effect of the factors independently on entrepreneurial intentions using linear regressions. The model accounts for 35% of the variance in entrepreneurial intentions. Five of the factors including perceived desirability, dissatisfaction, and self-efficacy and risk tolerance were found to be significant predictors of entrepreneurial intentions. Pull factors and social recognition was found to be insignificant. Pull factors lost its predictive power in this model once control variables were excluded. The results are shown in Table 3. In sum, young graduates are more likely to behave entrepreneurially once the mooring variables are strong and the pull factors towards entrepreneurship are also strong.

Discussion

This study investigated determinants of entrepreneurial intentions from the perspective of push-pull-mooring migration model. The model was tested using 288 Youth Corp members (young graduates) in Nigeria. The result shows that the model is a good fit. Though the model had low predictive power when compared with other competing models (e.g., TPB, Ajzen, 1991; SEE, Shapero 1982), it provides a theoretical justification for the inclusion of many predictors of entrepreneurial intentions into a unifying model (Bansal et al. 2005). The pull and mooring factors were the only significant predictors of entrepreneurial intentions. The push factors were found to have an insignificant influence on entrepreneurial intentions. The mooring factors had the strongest influence on entrepreneurial intentions. In other words, the environmental factors (finance availability and government support), perceived desirability (subjective norm and personal attitude), risk tolerance and self-efficacy are important determinants of entrepreneurial intentions. This emphasizes the importance of the mooring factors in facilitating or impeding entrepreneurial decision. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to empirically examine mooring factors in the context of entrepreneurship research; most of the sub-components examined as the mooring factors have been empirically verified in extant literature as earlier mentioned. The findings of this study corroborate earlier findings with regard to the sub-components. For instance, personal attitude, subjective norm (or perceived desirability) supports Segal et al., (2005), Solesvik et al., (2012) and Iakovleva et al., (2011) while Franke and Lüthje (2004), confirms the impact of environmental factors (availability of finance and government support).

Second, the significant effect of pull factors lends supports to previous studies (Giacomin et al. 2011; Ismail et al., 2012). This confirms the importance of independence or autonomy (Douglas & Shepherd, 2005) and to some extent opportunities exploitation and profit motives in the decision to behave entrepreneurially (Giacomin et al. 2011; Caliendo and Kritikos 2009). The tendency to be ‘pulled’ into an entrepreneurial career seems plausible when an individual has received entrepreneurship education.

Finally, the effect of push factors was insignificant. This result lends support to previous findings (Ismail et al., 2012). However, following reports of higher entrepreneurial activities in developing countries due to unemployment and ‘dissatisfaction’s (Iakovleva et al. 2011), It was expected that the push factors will predict EI. A plausible explanation could be that previous studies examined job dissatisfaction and unemployment as ‘push factors’ with a significant contribution to self-employment (Ritsilä and Tervo 2002; Brockhaus 1980). Job dissatisfaction was not measured in our dataset since young graduates do not have a job yet. In addition, further analysis of the factors under investigation reveals a significant effect of dissatisfaction and unemployment on EI when entrepreneurship education is excluded using standard regression. This emphasizes the importance of entrepreneurship education in the decision to be self-employed. Hence, the perception of employment and dissatisfaction only act to push individuals towards entrepreneurship when entrepreneurship education is lacking.

Conclusion

Policymakers are making a concerted effort towards increasing entrepreneurship supply by encouraging students to opt for an entrepreneurial career path after graduation. This study provides some insights towards policy directions for increasing the supply of entrepreneurs. The impact of entrepreneurship education on EI shows the need for continuous monitoring and advancement of entrepreneurship development programmes. The strength of the mooring factors in predicting EI emphasizes the need to improve governmental support and provide easy access to finance for young graduates. Furthermore, it is very important that entrepreneurship is culturally imbibed by enabling a connection between young graduates and successful entrepreneurs in a mentor-protégé relationship. This may increase the self-efficacy of potential entrepreneurs and also engender a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship. It may also be worthwhile for policymakers to start deploying willing graduates (or students) to entrepreneurial ventures (including informal business sectors) across all trades during the mandatory one year NYSC program to enable the development of necessary human capital and business networks necessary to initiate and manage their enterprise when it eventuates. These crops of young graduates may also be empowered at the end of their service year with substantial seed capital to start-up.

Pull factors predicts EI when entrepreneurship education are controlled for evidencing the impact of entrepreneurship education on opportunity recognition, desire for autonomy and profit search. When entrepreneurship education is absence, unemployment, dissatisfaction with life, government and democracy drive EI. In other words, the perception of limited employment opportunities, discriminatory employment practices, and dissatisfaction with life, government and democracy are significant predictors of EI when entrepreneurship education is lacking. Accordingly, encouraging self-employment through modifying entrepreneurship education to include classroom teachings and on-the-job training may increase entrepreneurial self-efficacy and to the greater extent of new venture creation.

Limitations and suggestion for further studies

The PPM model of migration provides theoretically robust bases for including a number of predictors into a model. However, only the most common predictors of entrepreneurial intention are included in the model. Future studies might consider including other dimensions into the PPM model. In addition, the PPM model accounts for the effect of moderation of the mooring variables on the push/pull factors, the application of a robust and sophisticated statistical method such as the structural equation modeling (SEM) is recommended to test this effect. While the study controlled for some factors such as sex, age, entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial parents, these factors are possible mooring variables that can be examined using the SEM. Lastly, the study examined the entrepreneurial intent of young graduates (National Youth Service Corps members) of only a state in Nigeria. This limits the generalizability of the findings of this study. It is recommended that the model is further tested using a larger sample size from diverse cultural settings.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The Ajzen theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Armitage, CJ, & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–499.

Bandura, A (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freemann & Co.

Bandura, A. (1998). Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychology and Health, 13(4), 623–649.

Bansal, HS, Taylor, SF, James, Y. (2005). “Migrating” to new service providers: toward a unifying framework of consumers’ switching behaviours. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33(1), 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070304267928.

Brännback M., Carsrud, A.L., Elfving, J., Kickul, J., Krueger, N. (2006). Why replicate entrepreneurial intentionality studies? Prospects, perils, and academic reality. Paper presented at the SMU EDGE Conference, Singapore.

Brockhaus, RH. (1980). The effect of job dissatisfaction on the decision to start a business. Journal of Small Business Management, 18(1), 37–43.

Buenstorf, G. (2009). Opportunity spin-offs and necessity spin-offs. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing, 1(1), 22–40.

Caliendo, M., & Kritikos, A.S. (2009). “I want to, but I also need to”: start-ups resulting from opportunity and necessity, discussion papers no. 966 DIW Berlin.

Canedo, JC, Stone, DL, Black, SL, Lukaszewski, KM. (2014). Individual factors affecting entrepreneurship in Hispanics. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 29(6), 755–772. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-11-2012-0333.

Chen, CC, Greene, PG, Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Small Business Venturing, 13(4), 295–316.

Davidsson, P., (1995). Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions, RENT IX Workshop, Piacenza, Italy, November.

Douglas, EJ, & Shepherd, DA. (2002). Self-employment as a career choice: Attitudes, entrepreneurial intentions, and utility maximization. Entrepreneurial Theory and Practice, 26(3), 81–90.

Douglas, EJ, & Shepherd, DA. (2005). Entrepreneurial human capital and the self-employment decision. Paper presented at the entrepreneurial research exchange, Swinburne University, Melbourne, Australia. February.

Fatoki, O, & Patswawairi, T. (2012). The motivations and obstacles to immigrant entrepreneurship in South Africa. Journal of Social Science, 32(2), 133–142.

Fitzsimmons, J.R., & Douglas, E.J. (2005). Entrepreneurial attitudes and entrepreneurial intentions: A cross-cultural study of potential entrepreneurs in India, China, Thailand and Australia, Babson-Kauffman entrepreneurial research conference, Wellesley, MA. June.

Franke, N, & Luthje, C. (2004). Entrepreneurial intentions of business students: a benchmarking study. International Journal of Innovation & Technology Management, 1(3), 269–288.

Fu, J-R. (2011). Understanding career commitment of IT professionals: Perspectives of push-pull–mooring framework and investment model. International Journal of Information Management, 31, 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2010.08.008.

Gatewood, EJ, Shaver, KG, Gartner, WB. (1995). A longitudinal study of cognitive factors influencing start-up behaviors and success at venture creation. Journal of Business Venturing, 10, 371–391.

Georgios, KB. (2014). Impediments on the way to entrepreneurship. Some new evidence from the EU's post-socialist world. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 21(3), 385–402 https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-04-2014-0062.

Giacomin, O., Guyot, J-L., Janssen, F., & Lohest, O. (2007). Novice creators: personal identity and push-pull dynamics, CRECIS Working Paper 07/2007, Centre for Research in Change, Innovation and Strategy, Louvain School of Management, downloadable through https://dial.uclouvain.be.

Giacomin, O., Janssen, F., Guyot, J-L & Lohest, O. (2011). Opportunity and/or necessity entrepreneurship? The impact of the socio-economic characteristics of entrepreneurs, MPRA Paper No. 29506, March.

Giacomin, O, Janssen, F, Pruett, M, Shinnar, RS, Llopis, F, Toney, B. (2010). Entrepreneurial intentions, motivations, and barriers: Differences among American, Asian and European Students. International Entrepreneurship Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-010-0155-y.

Gilad, B, & Levine, P. (1986). A behavioral model of entrepreneurial supply. Journal of Small Business Management, 24(4), 45–51.

Hisrich, RD, Peters, MP, Shepherd, D (2005). Entrepreneurship 6ed. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company Limited.

Hoeppier, BB, Kelly, JF, Slaymaker, V. (2012). Comparative utility of a single-item vs. Multi-item measure of self-efficacy in predicting relapse among young adult. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 41(3), 305–312.

Hou, A.C.Y., Chern, C-C., Chen, H-G., & Chen, Y-C. (2009). Using demographic migration theory to explore why people switch between online games, Proceedings of the 42nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 1–9.

Huisman, D, & de Ridder, WJ. (1984). Vernieuwend Ondernemen, Utrecht: SMO.

Iakovleva, T, & Kolvereid, L. (2009). An integrated model of entrepreneurial intentions. Inernational Journal of Business and Globalisation, 3(1), 66–80.

Iakovleva, T, Kolvereid, L, Stephan, U. (2011). Entrepreneurial intentions in developing and developed countries. Education & Training, 53(5), 353–370. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911111147686.

Ismail, HC, Shamsudin, FM, Chowdhury, MS. (2012). An exploratory study of motivational factors on women entrepreneurship venturing in Malaysia. Business and Economic Research, 2(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5296/ber.v2i1.1434.

Jackson, JA (1986). Migration. In In aspects of modern sociology: Social processes. London and New York: Longman.

Jamali, D. (2009). Constraints and opportunities facing women entrepreneurs in developing countries a relational perspective. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 24(4), 232–251. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542410910961532.

King, R., (2012), Theories and typologies of migration: an overview and a primer, Willy Brandt series of working papers in international migration and ethnic Relations, March.

Kolvereid, L. (1996). Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrepreneurship theory and pracitce, 21, 47–57.

Krueger, NF, Reilly, MD, Carsrud, AL. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 411–432.

Krueger, NJ, & Carsrud, A. (1993). Entrepreneurial intentions: applying the theory of planned behaviour. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 5, 315–330.

Lee, L., Wong, P. K., & Foo, M. D., (2005), Antecedents of entrepreneurial propensity: findings from Singapore, Hong-Kong, and Taiwan, MPRA paper No, 2615 retrieved online at http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/2615.

Liñán, F., & Chen, Y-W. (2006). Testing the entrepreneurial intention model on a two-country sample, working paper, University Autonoma de Barcelona, Documents de treball d'economia de l'empresa, June.

Liñán, F, & Chen, Y-W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1540-6520.2009.00318.x.

Linan, F, Nabi, G, Krueger, N. (2013). British and Spanish entrepreneurship intentions: A comparative study. Revista de Economia Mundial, 33, 73–103.

Luthje, C, & Franke, N. (2003). The ‘making’ of an entrepreneur: testing a model of entrepreneurial intent among engineering students at MIT. R&D Management, 33(2), 135–147.

Moon, B. (1995). Paradigms in migration research: Exploring ‘moorings’ as a Schema. Progress in Human Geography, 19(4), 504–524.

Noorderhaven, N, Thurik, R, Wennekers, S, van Stel, A. (2004). The role of dissatisfaction and per capita income in explaining self-employment across 15 European countries. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(5), 447–466.

Ozaralli, N, & Rivenburgh, NK. (2016). Entrepreneurial intention: antecedents to entrepreneurial behavior in the U.S.A. and Turkey. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 6(3). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-016-0047-x.

Reynolds, PD, Camp, SM, Bygrave, WD, Autio, E, Hay, M. (2001). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2001 Executive Report, Kauffman Centre for Entrepreneurial Leadership.

Ritsilä, J, & Tervo, H. (2002). Effects of unemployment on new firm formation: Micro-level panel data evidence from Finland. Small Business Economics, 19(1), 31–40.

Sarasvathy, SD (2004). Constructing corridors to economic primitives. Entrepreneurial opportunities as demand-side artifacts. In JE Butler (Ed.), Opportunity-identification and entrepreneurial behavior, (pp. 291–312). Connecticut: Information Age Publishing Inc..

Segal, G, Borgia, D, Schoenfeld, J. (2005). The motivation to become an entrepreneur. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 11(1), 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550510580834.

Shapero, A (1982). Social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In C Kent, D Sexton, K Vesper (Eds.), The Encyclopaedia of entrepreneurship, (pp. 72–90). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Singh, S, Simpson, R, Mordi, C, Okafor, C. (2011). Motivation to become an entrepreneur: A study of Nigerian women’s decisions. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 2(2), 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1108/20400701111165641.

Smallbone, D, & Welter, F. (2001). The distinctiveness of entrepreneurship in transition economies. Small Business Economics, 16(4), 249–262.

Solesvik, M. (2013). Entrepreneurial motivations and intentions: Investigating the role of education major. Education+Training, 55(3), 253–271.

Solesvik, M, Westhead, P, Kolvereid, L, Matlay, H. (2012). Student intentions to become self-employed: the Ukrainian context. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(3), 441–460.

Thurik, R, Carree, MA, van Stel, A, Audretsch, DB. (2008). Does self-employment reduce unemployment? Journal of Business Venturing, 23(6), 673–686.

Thurik, R., & Dejardin, M. (2012). Entrepreneurship and culture. Marco van Gelderen, Enno Masurel. Entrepreneurship in context, Routledge, pp.175-186, 2012, Routledge studies in entrepreneurship, 978-0-415-89092-2. <halshs-00943684>.

Uhlaner, L, & Thurik, R. (2007). Post-materialism influencing total entrepreneurial activity across nations. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 17(2), 161–185.

Van Gelderen, M, & Jansen, P. (2006). Autonomy as a start-up motive. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 13(1), 23–32.

Verheul, I, Thurik, R., Hessels, J. & van der Zwan, P. (2010). Factors influencing the entrepreneurial engagement of opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs, EIM Research Reports, H201011, March, 1–24.

Zellweger, T, Sieger, P, Halter, F. (2011). Should I stay or should I go? Career choice intentions of students with family business background. Journal of Business Venturing, 26, 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.04.001.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Nkechi Ojiagu for her valuable insight during the preparation of the manuscript. The authors acknowledge the participants in the Entrepreneurship and Informal economy section during the 17th IAABD conference in Arusha, Tanzania for their feedback in improving the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funding was received from any third party funding agency or institutions. The funding was provided by the authors.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first author OO, analyzed the data collected for the study and prepared the manuscript while the second author NA, edited the draft and provided technical support in mentoring the first author. The third author NI, revised the literature review section and provided technical support in the methodology section. Also, all the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

Obinna Christian Ojiaku is a Lecturer in the Department of Marketing and the Department of Entrepreneurship Studies, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka. He is also a Doctoral student in the same institution. He has presented papers in local and international conferences and published in Business and Economics Research, International Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research, Journal of Business Management and Economics among others.

Anayo D. Nkamnebe is a professor of Marketing at Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka. He has presented papers at both local and international conferences and published widely.

Ireneus C Nwaizugbo is a professor of Marketing at the Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka. He is well researched and has presented papers at international conferences.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ojiaku, O.C., Nkamnebe, A.D. & Nwaizugbo, I.C. Determinants of entrepreneurial intentions among young graduates: perspectives of push-pull-mooring model. J Glob Entrepr Res 8, 24 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-018-0109-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-018-0109-3