Abstract

Many degradation processes of cultural heritage objects are associated with unsuitable microclimatic conditions. One of the most ubiquitous deteriorations is the crystallization of salts in pores, which can accelerate the erosion rate of masonry historical relics. In this study, the microclimate of the burial tomb and exfoliation of sandstone in the Yongling Mausoleum of the Former Shu Dynasty in Chengdu were monitored for 1 year to determine the development of the degradation. We established a connection between the monitoring data and exfoliation variations of the stone with time. To predict the deterioration of the stone, a three-dimensional computational finite element model was used to simulate the detailed process of the thermo-hygrometric performance that led to salt crystallization and artwork deterioration. Two results were obtained. In the simulation of the microclimate, the temperature ranged from 15 to 22.6 °C, and the relative humidity was heterogeneous and varied between 60 and 100%. The other was the relationship between the microclimate and exfoliation. It was found that the exfoliation was more severe in the higher relative humidity areas where the water vapor frequently interacted with the relics. The crystallization and hydration of sulfate produced stress, which damaged the stone relics. These results provide a rationale analysis and a reference for better management of the environmental interactions and reduction of the environmental impacts in the subsequent scientific conservation of ancient Chinese cultural relics in tombs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The composition and degradation of cultural heritage objects often consist of complex systems with multiple physical and chemical processes [1]. An unsuitable environment can accelerate the deterioration of cultural heritage objects [2]. The deterioration of stone relics due to salt crystallization is ubiquitous in the conservation of stone cultural heritage objects [3]. It is visible at the macro-scale progressing from the surface to inner layers and causing loss of material via blistering, powdering, exfoliation, and detachment [4]. The degradation caused by salt is mainly due to the various destructive stresses exerted by salt in the crystallization and hydration processes. There are five mechanisms involved in this process: crystallization pressure, hydration pressure, thermal expansion, osmotic pressure, and chemical weathering [5].

When the environmental changes cause the concentration of the salt solution to increase, even with slight fluctuation, different types of salts can crystallize in different positions. The crystal growth migrates from the large to small pores, and accordingly, stress is generated in the microstructure of the material. The more soluble salts precipitate at greater heights [6].

The solubility of most salts is related to temperature, and changes in temperature promote the phase transition of salts [7]. This has been fully demonstrated. With the development of new research, the influence of humidity on the deterioration of stone has also been discussed [8,9,10,11]. Scholars have given a detailed description of the damage to cultural relics triggered by humidity variations [12]. Salt dissolved in water enters the cultural relics by capillarity and infiltration as liquid [13]. Water vapor also enters the porous material through condensation and hygroscopicity. The water inside the pores acts as a carrier of the saline liquid and transports it upwards [14]. When the salt solution enters the porous material, the internal salt concentration increases, and the saturated vapor pressure of the salt solution is lower than that of pure water, leading to a higher tendency to condense water vapor from the environment. As a result, humidity has a great influence on the salt weathering of stone historical relics.

Several studies have analyzed monitoring data and microclimatic factors [15, 16] to determine the most suitable environment for cultural relics in recent decades. Understanding and predicting heritage systems are the key points [17].

Numerical modeling can provide more detailed scenarios and can be used to assess the effects of environment and microclimate changes before the control methods are implemented [18, 19]. This non-invasive and visual [20] method is increasingly becoming an important tool in conservation studies of heritage microclimate [21], and it has been applied in multiple sites [11, 22,23,24].

Photographic monitoring is one of the most common methods of morphological survey, which is cost-effective and easy to operate, and it does not damage the surfaces and interiors of the objects. The degradation of cultural heritage objects is visible and can be recorded by taking pictures periodically.

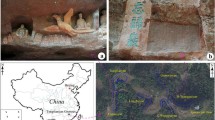

In this study, the red sandstone relics preserved in the royal tomb in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China, were studied. Based on the historical photos, the relics in the mausoleum have suffered serious salt weathering with a continuous exfoliation. This study has two aims. The first aim was to assess the indoor microclimate of the tomb in detail and define the boundary conditions of the numerical model. In fact, using the finite element method, a three-dimensional computational model was created to investigate the distribution of the outdoor and indoor thermo-hygrometric parameters. The second goal was to investigate the degradation of the material under micro-environmental conditions and improve the environmental management for the most effective cultural heritage preservation (Fig. 1).

Description of the mausoleum

This part is carried out from the aspects of archaeological excavation, tomb structure, distribution and mechanical properties of stone cultural relics, preservation and construction actions, and value assessment.

Excavation and preservation

The Yongling Mausoleum is located at No.10 Yongling Road, in the Jinniu District, Chengdu, Sichuan Province(31°N, 103°E) (Fig. 2). It is the first imperial mausoleum excavated following scientific instructions from modern archaeologists in China. The excavation was carried out in 1942, presided by Hanji Feng (1899–1977 AD) [25].

According to the imperial eulogical essay records, the owner of Yongling Mausoleum was Wang Chien (847–918 AD), the founding emperor of the Former Shu Dynasty, who was an outstanding ruler of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. China proper was in great turmoil during that time. During Wang Chien’s reign, the areas of Sichuan, Chongqing, southern Shaanxi, southeastern Gansu, and western Hubei had stable social environment and sustainable economic and cultural development which contributed to the development of the Song Dynasty [26]. The mausoleum is a representative remain of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms, and relics in it are important materials for research on the politics, economy, culture, religion, and other aspects of that period.

Since the date of the excavation of the Yongling Mausoleum, a series of preservation and construction actions have been taken to protect the important cultural heritage. Main preservation projects that affected the structure and stone materials of cultural relics are shown in Table 1.

Structure and stone relics

The Yongling Mausoleum is built on the ground, differently from other underground tombs in China. With a round-shaped dome, the grave mound is composed of yellow rammed earth with a diameter of 80 m and a height of 15 m. The burial chamber is in the middle of the mound, and it is accessed through an artificial channel that is about 29.74 m long. The mausoleum and stone relics inside are mainly made of red sandstone [27], and their main characteristics are presented in Table 2.

The chamber, vaulted with 14 arches, is over 23 m long, and circa 6 m wide and high. The first arch is a triple arch, the second arch is singular, and the other arches are double arches. There are murals in the antechamber, and the stone cultural relics are concentrated in the main hall and postchamber.

In the main hall, 24 Gigakus hold 23 pieces, and 20 types of instruments are carved on three sides on the coffin platform. There are 4 Gigakus on the south side and 10 Gigakus each on the east and west sides. There are 6 stone carvings on both sides of the coffin. They are facing the door and holding the coffin in their hands. The sandstone basin is located at the end of the main hall.

The imperial bed in the postchamber is carved with dragon-playing beads and cloud patterns, with a sitting statue of Wang Chien, which is the unique stone statue of the ancient emperor unearthed in China [26].

Experimental studies

The sensors of environmental monitoring were deployed according to the characteristics of the tomb structure. Based on the fundamental thermodynamic relations and monitoring data, a finite element model was created to obtain the temperature and relative humidity distribution.

Outdoor and indoor microclimatic monitoring

Automatic recorders (MicroWise system) were used to collect the data on main thermo-hygrometric parameters, including the air temperature (T) and relative humidity (RH) of the microclimate, from December 2015 to December 2016. Nine sensors were placed according to the structure of the tomb (Fig. 3) and recorded the parameters hourly using temperature probes (Ts: range of −20/60 ℃, the accuracy of 0.2 ℃, resolution of 0.02 ℃) and psychrometric probes (RH: range of 0–100%, the accuracy of 2%, resolution of 0.5%). There were 3 sensors, one outside the door and the others in the mausoleum passage. 2 sensors were in the antechamber, 3 sensors were in the main hall, and 1 sensor was in the postchamber.

Numerical modeling

Three-dimensional physical model of the inside of the tomb

There have been many cases of numerical calculations used to analyze the transfer of temperature and humidity in the air [28]. The heat and moisture transfer caused by the temperature difference of the building has been studied in detail [29, 30]. Building walls also had an impact on the heat and moisture transfer characteristics in the space [31]. Qin et al. [32] established a heat and moisture transfer model and calculated the coupled heat and moisture transfer process of the material, and introduced the transfer function method to solve the equation. Then the transient temperature and moisture distribution of the material were obtained. Lv [33] calculated the temperature and relative humidity transfer of the model based on the fundamental thermodynamic relations. The numerical solution provides transient temperature and moisture content for the building indoor. Janetti M. et al. [34] also evaluated the feasibility and numerical quality of numerical computations.

The simulation software was used to establish a model of the internal space of the Yongling Mausoleum (Table 3) that consists of an antechamber, main hall, and postchamber as visible in Fig. 4. The simulation computing domain was composed of the contact wall inside and around the mausoleum chamber. The physical model was treated using an unstructured grid refinement divided into 29882 grids and 5348 vertices (Fig. 5).

Model parameters

By defining the material heat transfer parameters and solving the heat balance equation, the thermal analysis value of each node is calculated. The curvilinear equation was calculated using the curve of the monthly average temperature and relative humidity in 2016 (Fig. 6).

where T is the monthly average temperature; t is the time in hour; and RH is the relative humidity.

The physical parameters of the model were set using the data collected in January 2016, which were the average temperature and relative humidity at points H and F in Fig. 3.

Governing equations

Heat transfer

The applied heat transfer module uses a building material heat transfer model, and its transient mathematical model is

where ρ is the density; Cp is the heat capacity; T is the temperature; q is the heat dissipation; Q is the heat; δp is the steam permeability; keff is the equivalent thermal conductivity; Psat is the saturated air pressure; RH is the relative humidity; and Lv is the latent heat of evaporation.

The heat transfer inside the tomb spread with the wet air, and its transient mathematical model is

where Qp is the heat related to the change in the pressure; Qvd is the heat related to the viscous dissipation; and k is the thermal conductivity.

Water transfer

Because the relative humidity inside the tomb is related to the exchange of the water content, a simulation analysis of the water transmission in the air was conducted. The applied transient mathematical model being

where Mv is the mass of the steam; cv is the concentration of the steam; D is the diffusion coefficient; csat is the saturated steam concentration; and ∅ is the porosity.

Photography monitoring

The transportation and crystallization of a salt solution cause significant damage to stone cultural relics and often cause exfoliation. The photos used in the analysis were taken in 1964, 1990, 2002, 2010, 2010, 2015, and 2017. In the middle of 2015, the surface cleaning of the stone cultural relics was completed. The photos taken in 2015 were taken in the fourth quarter of the year, and the photos taken in 2017 were taken at the beginning of the year. During the microclimatic monitoring period (from 2015 to 2017), there was no manual intervention on the coffin bed.

Results and discussion

The microclimate of the tomb was comprehensively analyzed through measurement data and simulated data. Sections were performed on temperature and relative humidity fields to research regional differences. Based on the investigation of exfoliation of stone cultural relics, the distribution of deterioration was drawn. The area of peeling (1964–2017) was calculated, so as the increasing area of the Gigakus by exfoliation from 2015 to 2017. The degradation mechanism was discussed by combining the characteristics of the microclimate and the distribution of exfoliation during different times.

Microclimate

Measured data

The temperature and relative humidity data recorded during the monitoring period were analyzed using box plots, and the standard deviation and average daily floating parameters were introduced. The standard deviation is defined as

where σ is the standard deviation; xi is the measured value; and μ is the average value.

The daily fluctuations are an important indicator of the differences between the highest and lowest temperature and relative humidity values. The value can be used to evaluate the stability of the cultural heritage environment. The average daily fluctuation was calculated as follows:

where \(\stackrel{\mathrm{-}}{\text{A}}\) is the average daily fluctuation value; and xmax is the maximum value; xmin is the minimum value.

As is shown in Fig. 7, during the monitoring period, the temperature range at point A outside the tomb was ranging between 12.5 and 21.5 °C (lower quartile and upper quartile). Due to the heat insulation effect of the tomb, the temperature change between the tomb’s passage and the outside door was small. The temperature inside the tomb (point C to point I in Fig. 7) was relatively constant ranging between 15 and 22.6 ℃ (lower quartile and upper quartile).

The relative humidity of the tomb in the Yongling Mausoleum is shown in Fig. 8. The relative humidity at point A was ranging between 84.3 and 99.4% (lower quartile and upper quartile). The relative humidity at points C to I was ranging between 80 and 100% (lower quartile and upper quartile). The measurement points on the west and east sides (points G and H) were more prone to high humidity than those in the other areas. The dispersion at each monitoring point was similar. The relative humidity outside the tomb was affected by the weather in Chengdu. Because of the building’s protection, the relative humidity varied less at points B and C. The relative humidity at points E, F, and I in the central area was between 81% (lower quartile) and 97% (upper quartile). Points D, G, and H were located on the wall. The relative humidity was between 80 and 100%, and the median relative humidity was 92%. The median relative humidity in the antechamber was 89%.

Simulated data

The thermo-hygrometers located at fixed points provided limited environmental data. These data were imported into a numerical model to calculate the temperature and relative humidity distribution of the tomb, to fully understand how the environment changed. The data for the numerical model in any month could be used to obtain the maximum value, the minimum value, and the instantaneous value. As an example, September was selected, and the extreme values of the model sections were determined (Fig. 9). The maximum temperature was 26.54 ℃ in the upper part of the antechamber, and the minimum temperature was 19.79 ℃ above the coffin bed in the main hall. The maximum relative humidity was 96.44% in the middle of the main hall, and the minimum relative humidity was 79.12% in the upper part of the antechamber.

The rainy season in Chengdu is concentrated from June to September, so the data for July 30, 2016, were selected. The temperature analyses are shown in Fig. 10, Fig. 11, and the relative humidity analyses are shown in Fig. 12, and Fig. 13.

In the temperature simulation field, the temperature was unevenly distributed in the tomb from north to south (Fig. 10). The temperature was slightly higher in the antechamber than in the center chamber and the postchamber. The temperature of the central axis area was higher than on the two sides, with small differences. For the same width, the temperatures in the center chamber, and the postchamber did not change with increasing height.

There were differences in the distribution of the temperature field in the tomb at different heights. The temperature in the antechamber increased slightly with increasing height, while the temperatures in the main hall and postchamber were the same at different heights.

The simulation of the relative humidity field at different widths is shown in Fig. 12. The tomb was in a state of high relative humidity for a long time. At the same height, the relative humidity in the antechamber was lower than in the main hall and the postchamber. The relative humidity was higher in the front part of the main hall and postchamber. The relative humidity on the east and west sides was higher than along the central axis.

As the height increased, the relative humidity of the antechamber gradually decreased. In the main hall, the relative humidity gradually increased with a small amplitude. In the postchamber, the relative humidity increased with increasing heights. The relative humidity in the height range of 0–1 m where the cultural relics were relatively concentrated was lower than in the other areas.

Degradation mechanism

Deterioration patterns and distribution

For convenient monitoring and discussion, the Gigakus were labeled according to their orientations (Fig. 14). The graphic documentation related to the efflorescence and exfoliation exhibited variations in the distribution of the damage to the stone cultural relics in the tomb (Fig. 14). The efflorescence was more obvious in the middle and lower parts, especially on the lower parts of the 24 Gigakus located in the main hall. The exfoliation was concentrated in the lotus and the middle, as well as on the lower parts of the Gigakus.

The humidity and temperature in the tomb affected the transportation of water and salt, which in turn caused the stone cultural relics to suffer more seriously salt weathering (Fig. 15) and exfoliation (Fig. 16).

Exfoliation of stone

The spatiotemporal variations in the exfoliation were estimated from the photographic documentation and site observations. First, the distortion in each photo was corrected using specific tools, and then, the graphic relief was converted into a digital format using a graphics software package (AutoCAD). The surface covered by exfoliation was evaluated using the image analysis tools in AutoCAD and was registered onto a photogrammetric base map. The exfoliation varied with the year and location. The comparisons among the different maps of the Gigakus were used to quantify the variations in the diffusion of the damage and the microclimate. Efflorescence and exfoliation from 1964 to 2017 on Gigakus were investigated (Fig. 17).

The distributions of the exfoliation with time were illustrated using different colors on the photos for the years from 1964 to 2017 (Fig. 18). The investigation revealed that due to the influence of the salinity, the prominent parts of the Yongling Mausoleum stone cultural relics such as the faces, hands, and instruments peeled off over time, and there were temporal and spatial variations in the areas affected by the salinity.

From 1964 to 2017, the area of peeling was counted for the heads, instruments, hands, and costumes (Fig. 19). E-01 experienced the largest amount of overall exfoliation, followed by S-02. The peeling area of W-07 was the smallest. E-01 and S-03 experienced the largest and smallest amounts of exfoliation of the head, respectively. E-01 and W-07 experienced the largest and smallest amounts of exfoliation, respectively, of hands and instruments. S-02 and E-03 experienced the largest and smallest amounts of exfoliation of the costumes, respectively. The average exfoliation areas of the east, south, and west Gigakus were calculated, and that on the east side was greater than that on the south and west sides (Additional file 1: Fig. S1–S3).

The environmental monitoring data for this study from 2015 to 2016 was selected, and the area of the new peeling area in the photos of Gigakus during this period was divided into the areas on the heads, hands, instruments, and costumes (Fig. 20).

The images and figures related to the exfoliation show that there were differences in the new peeling areas of the stone in the tomb, depending on the directionality. The south side exhibited the fastest change in the average new area of exfoliation, followed by the east side. According to direct observations and recordings during the monitoring period, the W-09 experienced the smallest amount of exfoliation, with an area of 62.16 mm2, while S-02 experienced the largest amount of exfoliation, with an area of 1446.37 mm2. W-04 and W-07 experienced the largest and smallest amounts of peeling of the head, respectively. E-02 and W-07 experienced the largest and smallest amounts of peeling, respectively, of the hands and instruments. S-02 and W-07 experienced the largest and smallest amounts of peeling of the costume, respectively.

The percentage of the new area to the cumulative exfoliation of each part of the Gigakus was calculated (Fig. 21). S-03 and W-07 experienced the largest and smallest proportions of the new peeling area on the heads, respectively. E-03 and W-09 experienced the largest smallest and proportions of new peeling, respectively, of the hands and instruments. S-03 and E-10 experienced the largest proportions of new costume peeling, respectively. The percentage of new exfoliation to the total exfoliation was larger on the south side than on the west and east sides. From 2015 to 2017, the contribution to the overall peeling volume was larger on the south side than on the west and east sides, which had a certain relationship with the fact that the east side had previously undergone large-scale exfoliation and the surface structure had reached a certain level of stability.

Exfoliation and microclimate

The tomb is built on the ground and there is a 32 m passage from the tomb door to the outside. The most likely cause of the exfoliation was the structural damage caused by the entry of water and salt into the stone. When the microclimate changed, the salt moved with the water and underwent a repeated phase transition from an aqueous solution to a crystallized salt solution, causing damage [8, 35]. The optimal environmental conditions for stone conservation are temperature range of 15–25 ℃, and relative humidity values of 20–60% [36, 37]. Studies have shown that mirabilite was most susceptible to crystallize and expand at the relative humidity of 60–75%. Time and humidity were the influences of gypsum expansion [38]. During the monitoring period, the temperature in the tomb remained between 15 and 22.6 ℃ with small variations, while the relative humidity varied between 60 and 100%. Thus, the effect of the relative humidity on the stone was greater than that of the temperature.

When moist air encounters relatively dry stone, water vapor exchange easily occurs on the surface, which increases the relative humidity of the stone. If salt solution enters the stone, the porous structure of the stone promotes the capillary action, causing more solution to enter the stone. Then, the internal salt concentration and the water content of the porous material increase, and the capillary action is further enhanced. The vapor pressure of the salt solution is lower than that of the pure water, resulting in a higher tendency of water vapor from the environment to condense to equalize the difference between the vapor phases and increase the deep moisture. These two processes affect each other, so salt weathering is a dynamic process, which further accelerates the exfoliation caused by the salt infestation. The average daily change in the amplitude was greater on the east side than on the west side, and the change in the relative humidity caused the change in the internal absorption of the stone cultural relics, resulting in the changes in the salt concentration and transport, which in turn affected the crystallization and dissolution of the salt solution.

According to the sampling and analysis, the salts that are causing the current exfoliation of the stone relics are mainly CaSO4 and a certain amount of Na2SO4. Under the same conditions, the crystallization pressures of the salts are as follows CaSO4 > Na2SO4 > CaSO4·2H2O ≫ Na2SO4·10H2O [39]. Sulfates do not undergo a simple phase transition process during precipitation, and hydration usually occurs to generate different salts. Na2SO4 is converted to Na2SO4·7H2O below 22 °C [40]. When the temperature is between 22 and 32.4 °C, the sulfates form Na2SO4 first and then transition to Na2SO4·10H2O. When the temperature is above 32.4 °C, the sulfates crystallize to form Na2SO4 (Fig. 22) [41]. These processes not only produc e large crystal pressure but also produce hydration pressure. The volumes of the salts expand as the number of crystals in the water increases, which also causes damage to the stone relics.

Phase diagram for the system Na2SO4-H2O in a plot of relative humidity versus temperature. The continuous lines indicate the boundaries of the stable phases. The discontinuous line corresponds to a solution in metastable equilibrium with respect to thenardite and supersaturated with respect to mirabilite [41]

At 20 °C, CaSO4·1/2H2O hydration occurs to generate CaSO4·2H2O, and the hydration pressure generated by CaSO4·2H2O increases significantly as the humidity increases (Fig. 23) [42]. The hydration pressure generated when the relative humidity is 100% is near twice the force generated when the relative humidity is 60% [43]. The degree of calcium sulfate destruction mainly depends on the relative humidity, because it will precipitate inside the stone, causing greater damage when the relative humidity is high [44].

Phase diagram for the system CaSO4-H2O in a plot of relative humidity versus temperature, where: a gypsum-anhydrite equilibrium curve; b gypsum–hemihydrate equilibrium curve [42]

Through a more detailed analysis of the microclimate using the finite element model, it was found that the relative humidity was larger on the east and west sides in the front area of the main hall (Fig. 12), and the relative humidity in the front area of the coffin bed was lower (Fig. 13a–c). The water vapor exchange between the two areas was relatively frequent, which is also the reason why the degradation of E-01 and W-01 was more serious than that of the other Gigakus on the same side. Based on the comparison, the value and range of the relative humidity were slightly larger on the east side than on the west side (Fig. 12), and E-01 was the most seriously damaged. The difference in the relative humidity triggered diversity in the sulfate hydration reaction, resulting in differences in the exfoliation of the stone relics on the east and west sides. S-02 and S-03 face the door of the tomb, and the high temperature and low humidity at their locations also caused exfoliation.

The relative humidity was slightly lower in the middle of the coffin bed than on the west side, while the relative humidity was the same in the wall areas on both sides (Fig. 13a–c), and the exfoliation of E-02 to E-08 was more serious than that of W-02 to W-08. The relative humidity in the rear part of the main hall was high, but the relative humidity in the coffin bed was low, and there was still a frequent exchange of water vapor, resulting in the more serious exfoliation of E-09 to E-10 and W-09 to E-10.

The areas with extremely low temperatures and high relative humidities were the places where the salt solution crystallized and the hydration changed frequently, which were prone to cause stone exfoliation and damage. While paying attention to the exfoliation of the stone is important, it is also necessary to monitor the environment in these areas and to undertake effective climate regulation in the future to prevent further exfoliation. According to the existing microclimate model and the photographic monitoring results, instruments can be arranged at the front part of the antechamber (near the door), on the east side in the front part of the main hall, and on the west side in the front part of the postchamber. Temperature and relative humidity data can be obtained to monitor the microclimate of the tomb, achieve optimization of the layout of the environmental monitoring instruments, and avoid excessive monitoring using too many instruments.

Conclusions

In this study, a finite element model of the microclimate based on the conditions of boundaries was created to obtain the temperature and relative humidity distributions in the tomb in the Yongling Mausoleum. The model was used to obtain the temperature and relative humidity in any time and in any area. The microclimate field in the rainy season was analyzed. The antechamber had a high temperature and low relative humidity compared with the main hall and the postchamber. The photographic monitoring of the stone cultural relics was used to determine the total and the increases in the areas of exfoliation during the monitoring period on the south, east, and west sides of the coffin bed. It was found that the changes were the greatest on the south side, due to the distributions of the temperature and relative humidity. On the east side of the front part, the relative humidity was low near the coffin bed and high near the wall, so the water vapor interacted with the stone frequently, which led to sulfate hydration and crystallization. The crystallization pressure and hydration pressure damaged the stone relics. The exfoliation, microclimate monitoring data, and microclimate finite element model were used to determine the reasons for the differential deterioration of the cultural relics. This comprehensive method was demonstrated to be helpful in studying the relationship between the damage caused by salt crystallization and the microclimate conditions and the deepening of the decay process. This research does not include the exploration of cultural relics protection methods, and the exfoliation is still continuing. It can become a future research direction with the result of this study providing a scientific basis for environmental control and damage treatment.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- T:

-

Monthly average temperature (℃)

- t:

-

Time in hour (h)

- RH:

-

Relative humidity (%)

- ρ:

-

Density (kg m−3)

- Cp :

-

Heat capacity (J kg−1 K−1)

- q:

-

Heat dissipation (J)

- Q:

-

Heat (J)

- δp:

-

Steam permeability (m3 m−2 kPa−1 h−1)

- keff :

-

Equivalent thermal conductivity (W m−1 K−1)

- Psat :

-

Saturated air pressure (Pa)

- Lv :

-

Latent heat of evaporation (W m−2)

- Qp :

-

Heat related to the change in the pressure (J)

- Qvd :

-

Heat related to the viscous dissipation (J)

- k:

-

Thermal conductivity (W m−2 K−1)

- Mv :

-

Mass of the steam (kg h−1)

- cv :

-

Concentration of the steam (%)

- D:

-

Diffusion coefficient (m2 s−1)

- csat :

-

Saturated steam concentration (%)

- ∅:

-

Porosity (%)

- σ:

-

Standard deviation

- xi :

-

Measured value

- μ:

-

Average value

- \(\stackrel{\mathrm{-}}{\text{A}}\) :

-

Average daily fluctuation value

- xmax :

-

Maximum value

- xmin :

-

Minimum value

References

Monforti F, Bellasio R, Bianconi R, Clai G, Zanini G. An evaluation of particle deposition fluxes to cultural heritage sites in Florence Italy. Sci Total Environ. 2005;334–335:61–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.04.030.

Sawdy A, Price C. Salt damage at Cleeve Abbey, England. Part II: seasonal variability of salt distribution and implications for sampling strategies. J Cult Herit. 2005;6:361–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2005.10.002.

Trofimova E, Trofimov A. World subterranean heritage. Geoheritage. 2019;11:1113–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-019-00351-8.

Frasca F, Verticchio E, Caratelli A, Bertolin C, Camuffo D, Siani AM. A comprehensive study of the microclimate-induced conservation risks in hypogeal sites: the mithraeum of the baths of caracalla (Rome). Sensors. 2020;20(11):3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20113310.

Rodriguez-Navarro C, Doehne E. Salt weathering: influence of evaporation rate, supersaturation and crystallization pattern. Earth Surf Proc Land. 1999;24:191–209.

Arnold A, Zehnder K. Monitoring wall paintings affected by soluble salts. The conservation of wall paintings, proceedings of a symposium organized by the courtauld institute of art and the getty conservation institute. Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1991; pp. 103–135.

Sawdy A, Price C. Salt damage at Cleeve Abbey, England. Part I: a comparison of theoretical predictions and practical observations. J Cult Herit. 2005;6:125–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2005.03.003.

Franzen C, Mirwald PW. Moisture sorption behaviour of salt mixtures in porous stone. Geochemistry. 2009;69(1):91–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemer.2008.02.001.

D’Agostino D, Congedo PM. CFD modeling and moisture dynamics implications of ventilation scenarios in historical buildings. Build Environ. 2014;79:181–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2014.05.007.

D’Agostino D, Congedo PM, Cataldo R. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling of microclimate for salts crystallization control and artworks conservation. J Cult Herit. 2014;15(4):448–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2013.10.002.

O’Brien PF, Bell E, Santamaria SP, Boyland P, Cooper TP. Role of mortars in the decay of granite. Sci Total Environ. 1995;167(1–3):103–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-9697(95)04573-J.

Congedo PM, Baglivo C, D’Agostino D, Quarta G, Gloria PD. Rising damp in building stones: numerical and experimental comparison in lecce stone and carparo under controlled microclimatic conditions. Constr Build Mater. 2021;296:123713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123713.

Charola AE. Salts in the deterioration of porous materials: an overview. J Am Inst Conserv. 2000;39(3):327–43. https://doi.org/10.1179/019713600806113176.

Torres MIM, Freitas VP. Treatment of rising damp in historical buildings: wall base ventilation. Build Environ. 2007;42(1):424–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2005.07.034.

Sainz-Jimenez C, editor. The conservation of subterranean cultural heritage. London: Taylor and Francis Group; 2014. p. 51–8.

Benavente D, Sanchez-Moral S, Fernandez-Cortes A, Can˜averas JC, Elez J, Saiz-Jimenez C. Salt damage and microclimate in the Postumius Tomb, Roman Necropolis of Carmona Spain. Environ Earth Sci. 2011;63:1529–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-010-0815-9.

Balocco C. Daily natural heat convection in a historical hall. J Cult Herit. 2007;8(4):370–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2007.04.004.

Mah A, Mhb A, Yem A, Chateigner D. A review on physical and data-driven modeling of buildings hygrothermal behavior: Models, approaches and simulation tools. Energy Buildings. 2021;251:111343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2021.111343.

Akkurt GG, Aste N, Borderon J, Buda A, Calzolari M, Chung D. Dynamic thermal and hygrometric simulation of historical buildings: critical factors and possible solutions. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2020;118:109509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.109509.

Grau-Bové J, Mazzei L, Strlic M, Cassar M. Fluid simulations in heritage science. Herit Sci. 2019;7:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-019-0259-9.

Li Y, Nielsen PV. Commemorating 20 years of Indoor Air CFD and ventilation research. Indoor Air. 2011;21(6):442–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0668.2011.00723.x.

Malaurent P, Brunet J, Lacanette D, Caltagirone JP. Contribution of numerical modelling of environmental parameters to the conservation of prehistoric cave paintings: the example of Lascaux Cave. Conserv Manage Archa. 2007;8(2):59–76. https://doi.org/10.1179/175355206x202976.

Corgnati SP, Perino M. CFD application to optimise the ventilation strategy of senate room at Palazzo Madama in Turin (Italy). J Cult Herit. 2013;14(1):62–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2012.02.007.

Cutajar D, Farrugia PS, Micallef A. An integrated approach to the study of heritage sites. J Cult Herit. 2019;37:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2018.10.014.

Feng HJ. Discovery and excavation of the Yung Ling the royal tomb of Wang Chien. Arch Chin Art Soc Am. 1947;2:11–20.

Zhang YP. The Museum of Chengdu Yongling Tomb. Chengdu: Bashu Publishing House; 1999.

Feng HJ. Report on the excavation of the tomb of the former king of Shu. Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House; 2002.

Sýkora J, Vorel J, Krejčí T, Šejnoha M, Šejnoha J. Analysis of coupled heat and moisture transfer in masonry structures. Mater Struct. 2008;42:1153–67. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-008-9450-2.

Liu F, Jia BG, Chen BM, Geng WG. Moisture transfer in building envelope and influence on heat transfer. Procedia Eng. 2017;205:3654–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.10.229.

Shen XW, Li LJ, Cui WZ, Feng Y. Coupled heat and moisture transfer in building material with freezing and thawing process. J Build Eng. 2018;20:609–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2018.07.026.

Liu R, Huang YW. Heat and moisture transfer characteristics of multilayer walls. Energy Procedia. 2018;152:324–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2018.09.142.

Qin MH, Belarbi R, Aiet-Mokhtar A, Seigneurin A. An analytical method to calculate the coupled heat and moisture transfer in building materials. Int Commun Heat Mass. 2006;33(1):39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2005.08.001.

Lv XS. Modelling of heat and moisture transfer in buildings: I. Model Progr Energy Build. 2002;34(10):1033–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7788(02)00021-X.

Janetti M B, Ochs F, Feist W. Numerical quality of a model for coupled heat and moisture transport in COMSOL Multiphysics. In: 2nd central european symposium on building physics. 2013; 591–598.

Cardell C, Delalieux F, Roumpopoulos K, Moropoulou A, Auger F, Grieken RV. Salt-induced decay in calcareous stone monuments and buildings in a marine environment in SW France. Constr Build Mater. 2003;17(3):165–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0950-0618(02)00104-6.

UNI. UNI 10829: Luglio 1999, Beni di interesse storico e artistico—Condizioni ambientali di conservazione—Misurazione ed analisi. 1999. http://store.uni.com/catalogo/index.php/uni-10829-1999.html.

Aste N, Adhikari RS, Buzzetti M, Torre SD, Pero CD, Huerto HE, Leonforte F. Microclimatic monitoring of the Duomo (Milan Cathedral): risks-based analysis for the conservation of its cultural heritage. Build Environ. 2019;148:240–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.11.015.

Xiao YF, Yang HK, Luo J, Zhu YL. Determination of hydration of anthracite and expansion of glauber’s salt crystals. Site Investig Sci Technol. 1985;05:7–10.

Winkler EM, Singer PC. Crystallization pressure of salts in stone and concrete. Geol Soc Am Bull. 1972;83(11):3509–14. https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(1972)83[3509:CPSIS]2.0.CO;2.

Saidov TA, Pel L, Van Der Heijden GHA. Crystallization of sodium sulfate in porous media by drying at a constant temperature. Int J Heat Mass Tran. 2015;83:621–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2014.12.043.

Tsui N, Flatt RJ, Scherer GW. Crystallization damage by sodium sulfate. J Cult Herit. 2003;4(2):109–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1296-2074(03)00022-0.

Charola AE, Pühringer J, Steiger M. Gypsum: a review of its role in the deterioration of building materials. Environ Geol. 2007;52:339–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-006-0566-9.

Winkler EM, Wilhei EJ. Salt burst by hydration pressures in architectural stone in urban atmosphere. Geol Soc Am Bull. 1970;81(2):567–72. https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(1970)81[567:SBBHPI]2.0.CO;2.

Menéndez B. Estimators of the impact of climate change in salt weathering of cultural heritage. Geosciences. 2018;8(11):401. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8110401.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their great gratitude to Chengdu Yongling Museum, Beijing Guo Wenyan Cultural Relics Protection and Development Co., Ltd., China, University of Geosciences (Wuhan), and University of Science and Technology Beijing.

Funding

The research was financially supported by the design of reinforcement and anti-seepage and stone carvings protection and restoration project of the royal tomb of Wang Chien (Phase I).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HG and DC provided support and guidance for this study. YZ and XB performed analysis and drafted the manuscript. SL provided the samples and assistance in the study. BL made revisions to the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Exfoliation areas of the heads during 1964-2017. Figure S2. Exfoliation areas of the hands and instruments during 1964-2017. Figure S3. Exfoliation areas of the costumes during 1964-2017.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Cui, D., Bao, X. et al. Exfoliation of stone cultural relics under the microclimate in the Yongling Mausoleum of the Former Shu Dynasty. Herit Sci 10, 155 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00788-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-022-00788-1