Abstract

Background

This study investigates the determinants of career change for individuals who change their job to become a teacher in vocational education and training (VET) as a second career. The question of what motivates individuals to forfeit their original occupation to become a teacher is important for policy making not only in times of teacher shortages but also in light of the quality of individuals that can be motivated to change their career mid-life to become a teacher.

Methods

First, the empirical analysis uses pairs with the same observable characteristics of teachers and non-teachers in Switzerland to compare the relative wage position in their former occupation of those who have chosen to change career into teaching. We indicate the quality of these career changers primarily by their pay in the former occupation. Second, we investigate the wage prospects of career changers by exploring the counterfactual situation to the decision to become a teacher (teacher’s expectations for a career in the former occupation or as a teacher) and therefore we apply multivariate regression techniques to account for observable differences between individuals.

Results

The results show that individuals who change their careers to teaching in VET earned, on average, more in their first career than comparable workers in the same occupation. The findings also demonstrate that the average career changer still expects to earn significantly more as a teacher than in their former career. However, the study shows that one-third of the career changers expect a wage loss.

Conclusion

Although the average teacher tends to rank among the better earners in his or her original occupation, the majority of career changers expect to earn more as a teacher than in their original occupation. This finding shows that the average wage level at vocational schools can compete with average wage levels in the rest of the economy. However, substantial heterogeneity exists given that about one-third of career changers are prepared to accept a cut in wage after changing to teaching. One probable explanation is the very high relevance of non-monetary factors that make teaching a more attractive option, at least for some individuals.

JEL-codes

C21, I20, J24, J45, J62

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The present study investigates the determinants governing change to a career in teaching. The question of what motivates individuals to forfeit their original occupation to become a teacher is important for policy making not only in times of teacher shortages but also in light of the quality of individuals that can be motivated to change their career mid-life to become a teacher.

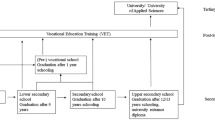

More specifically, we use a particular feature of the Swiss vocational education and training (VET) system to study career change—that teachers of job-related subjects cannot choose teaching as their first career but can only become teachers after (a) acquiring the highest education qualification in their job category and (b) accumulating a certain number of years of job experience. Thus, all teachers of vocational subjects have changed careers. This special feature of the Swiss education system allows us to analyze a large number of career changers turning to teaching and to draw conclusions about how educational systems can attract high-quality career changers into teaching.

For our empirical analyses, we assess a unique data set of teachers who decided to change their careers to teaching. The data set is representative of the whole German- and French-speaking Switzerlanda. For our comparative analyses, we use data on the workforce from the Swiss Labor Force Survey (SLFS). We use the former wage position compared with the average wage of similar individuals in the former occupation of the teachers as an indicator for their performance in their former occupation as well as for teaching qualityb. With this approach, we follow Chingos and West ([2012]), who showed that better teachers leaving the teaching occupation earn more in the outside career and therefore provide evidence of a positive correlation between teaching quality and earnings outside teaching.

Our results show first that those who change careers to teaching (who are on average 40 years old) do not change careers because of a lack of (financial) success in their original career. Although the results are unsurprisingly heterogeneous, we can nevertheless explain at least part of this heterogeneity. Second, although the average teacher tends to rank among the higher earners in their original career, the majority of career changers expect to earn more as a teacher than in their original career. Again, we find a substantial heterogeneity: around one-third of career changers expect a wage reduction after changing.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section contextualizes our research with a description of the recruiting procedures for Swiss vocational education and training teachers followed by a brief review of the relevant literature. The “Methods and Data” section describes our data and outlines our research questions, and the “Results” section presents the empirical results and the final section concludes.

Recruitment of vocational teachers in Switzerland

The legal provisions governing the hiring of teachers for instruction in vocational subjects require candidates to meet two conditions. First, candidates must have the highest possible training qualification in the particular occupation, which in most cases is a professional education at tertiary level B (ISCED 5B)c or even an academic degree at tertiary level A (ISCED 5A)d. Second, they must have very good subject knowledge, i.e., a minimum of six months of occupational experience, with several years being the norm. Most teachers have a long history of job experience because the highest possible training qualification generally consists of practically oriented and occupationally specific training at an advanced level (57% of teachers in our sample have tertiary level B professional education and training), all of which involves many years of job experience. Extensive job experience is also apparent in our sample, with the average age of teachers being over 40 (see Table 1). Meeting all of these requirements an individual can be recruited by a vocational school as a teacher. Therefore, all vocational teachers in Switzerland are career changers. Only after recruitment – and besides teaching – teacher training starts. Individuals begin teacher training for full-time or sideline positions. Full-time teachers can teach full-time or part-time at vocational schools. Qualification for sideline teaching, by contrast, consists of much fewer training hours and, therefore, the certificate limits these teachers to teaching part-time and not full-time. We use the term sideline teachers to distinguish the teachers from those who are trained for full-time teaching but who may choose to teach part-time. For sideline teachers, their work at vocational school is precisely that – on the sideline of their work in their original occupation. The teachers are recruited from occupations being taught to students at the vocational schools. Therefore, the original occupations of the teaching staff reflect the respective apprenticeship market. The strong rooting of apprenticeship in the manufacturing sector also explains why more (one-third) vocational teachers than the working force average worked in industry and manufacturing prior to changing careers into teaching. One crucial factor directly affecting the monetary appeal of teaching at vocational schools is the competitiveness of the original occupations and business sectors in terms of the prevailing pay and working conditions.

Literature review

The existing literature on the choice of teaching as a (first) career investigates both factors governing candidate quality and aptitude and factors governing the quantity of teachers available in the workforce. Economic literature tends to focus on the relative wage as a factor influencing the quantitative and qualitative supply of teachers on the labor market. Non-monetary factors have also been studied but only to some extent because these factors are usually much more difficult to address empirically.

Most studies demonstrate a positive wage elasticity of labor supply (Chevalier et al. [2007]; Dolton [1990]; Dolton and Chung [2004]; Falch [2010]; Manski [1987]; Wolter and Denzler [2004]). These findings may be related to labor supply elasticity being influenced to some extent by how high the wage differential is in absolute terms. Labor supply elasticity appears very high in cases where teachers earn less than individuals in similar occupations, whereas elasticity is relatively low where teachers tend to earn more.

For the qualitative selection of the teaching occupation, the results of known empirical studies are less conclusive. Whereas US studies find ample evidence of negative selection in terms of cognitive criteria (see, e.g., Corman [1993]; Hanushek and Pace [1995]; Manski [1987]; Podgursky et al. [2004]; Stinebrickner [2001]), the results are less conclusive for German-speaking countries (see Denzler and Wolter [2009]).

What makes applying these data most difficult to the subject matter explored in this paper is that all of these studies focus on why people select teaching as a first career after graduation, i.e., there is a deficiency of comparable empirical studies investigating why people select teaching as a second career.

Therefore, to construct the hypotheses on career change for teachers we also use career change literature to explore the predictive factors of career change. Standard search and matching models (Burdett [1978]; Jovanovic [1979]; Mortensen [1986]; Neal [1999]) start by assuming that labor markets feature heterogeneous employers and employees as well as imperfect information. In these models, employee productivity is highest where there is the perfect match to the specific job. Because neither employer nor employee will know the optimal match in advance, employees will keep changing jobs until they achieve the perfect match. As a consequence of this search process, changing jobs correlates with increasing wages (Rubinstein and Weiss [2006]). However, individuals do not continuously change employers and careers because any change involves a loss of human capital and, therefore, of productivity and wage.

According to the standard human capital theory (Becker [1962]), assuming that wage corresponds to the workers’ productivity, jobs are associated with the acquisition of employer-, occupation- and industry-specific human capital that may be forfeited with a change of employer or—and even more—a change of career. The better match in the new job would therefore have to raise the productive value of general human capital enough to compensate for the loss in employer- and job-specific human capital. However, increased employer- and job specific skills lower turnover intentions (or a change of career) as employer-specific skills are less valuable to other employers (Doeringer and Piore [1971]).Corresponding to the logic of human capital theory, a change is all of the more unlikely the longer the period of investment in employer- and job-specific human capital. One should therefore be able to observe a lower incidence of job changes (with or without career changes) as a function of seniority. Furthermore, in addition to the standard human capital theory, the strategy of backloading the compensation profile (i.e., paying the worker less than his marginal productivity when young and more when old to increase workers motivation over the whole working career and to alleviate monitoring problems) also explains a decreasing propensity in employer change with seniority (Lazear [1979], Lazear [1981], Daniel and Heywood [2007]; Heywood et al. [2010]).

Refinements of the human capital theory (e.g., the skills weight theory, see Lazear [2009]) assume the existence of no general or specific human capital but only of different combinations of skills. These refinements suggest that, regardless of the existing duration of employment, mobility between employers, occupations and industries can still be high provided that the potential employment alternative requires a similar mix of skills (see, e.g., Geel et al. [2010]). For our hypotheses, this additional factor is relevant because a vocational teacher’s job not only calls for levels of expertise similar to those required in the former occupation but also requires above-average expertise levels (i.e., a long history of skill-building) in the original occupation. As we can assume that a large amount of the expertise accumulated in the former occupation can be transferred to the new one (teaching), it is likely that the probability of changing a career to teaching will not correlate negatively with seniority. In contrast, individuals who changed employers frequently also tended to be those who had already changed careers once or several times. The lack of consistency in their employment history makes it more difficult for these individuals to enter the vocational teaching occupation because they do not fulfill the relevant requirements (see the section on the recruitment of vocational teachers in Switzerland).

Furthermore, empirical work on the role of job characteristics (also non-monetary characteristics) suggests that labor supply is affected by the specific characteristic of a job (e.g., Altonjii and Paxson [1986]; Atrostic [1982]; Kunze and Suppa [2013]). More favorable working conditions affect job and life satisfaction (e.g., Cornelissen [2009], Lüchinger et al. [2010]) and job satisfaction or dissatisfaction may explain job changes (e.g., Clark [2001]; Cornelissen [2009]). Furthermore, job characteristics can also explain wage differentials (e.g., Wells [2010]). Therefore, in addition to earnings prospects, job quality in teaching may motivate individuals to change to teaching.

As for forecasting based on search and matching models, individuals will want to change to the teaching occupation only if they expect it to be a better match. However, the extent to which a higher wage is expected to be part of that better match remains unclear. The reason is first, we do not know the relative position of different jobs regarding the job characteristics and hence non-monetary benefits. Second, the assumption that higher productivity will translate to a higher wage (wage reflects productivity) does not automatically apply in the public sector, where schooling takes place. One feature of vocational schools is that all teachers receive the same wage, depending on age, canton, experience and training, independent of their original occupation. Wages are set by cantonal laws, and schools therefore have no room for maneuver in wage setting. The financial attractiveness of teaching therefore depends essentially on the wage level of the individual’s original occupation. Therefore, we expect that schools can choose among several candidates for teaching positions from occupations with relatively low wage levels, whereas schools will face difficulties finding suitable candidates from occupations with high compensation levels.

Furthermore, we hypothesize that teachers change to teaching when their cumulated future compensation bundle (monetary and non-monetary benefits) is superior in the teaching occupation compared with their former occupation.

Methods and data

Data

Because they are career changers, teachers in vocational education need to complete a pedagogical education in their first years of teaching in addition to teaching. We conducted the survey among all teacher trainees for vocational education at the Swiss Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (SFIVET). At the time of this study (spring semester 2010), three tertiary institutions were offering vocational teacher training in Switzerland but SFIVET, which provided the sample used for this paper, had a market share of over 80% of vocational teacher trainees.

Because we conducted the survey during classes, we achieved a response rate of 100%. The teachers completed the survey using either a computer-assisted questionnaire or, if no computer was available, an identical paper and pencil version. We tested the questionnaire in an extensive pre-test on teachers who had previously trained at SFIVET.

The information elicited in the survey comprises personal details, training, job experience, wage and wage expectations of the 483 respondents in German- and French-speaking Switzerland. About one half of the 483 teachers (230) were pursuing a degree qualifying them to be full-time vocational teachers. The other half of the respondents (253) was working toward a certificate qualifying them to be sideline vocational teachers. Despite the 100% response rate, some data were missing on account of item non-response. We excluded 93 observations (19%) from the analysis because of missing wage information or other important data, leaving a final dataset of 390 vocational teachers. Item non-response analyses show that the exclusion of the 93 observations should not influence or bias our resultse.

To compare those individuals who have chosenf to change career with similar individuals who have chosen to remain in their initial occupation, we sourced a comparison group data from the Swiss Labor Force Survey (SLFS). Because the vocational teachers in our sample opted to change to teaching at different points in time, we used three different cohorts (2004, 2006 and 2008) of the SLFS. To obtain the comparison group for the teachers, we excluded all individuals who would not have been able to become a teacher, i.e., the unemployed, pensioners, students, individuals without compulsory-post-schooling qualifications and individuals who were under 20 years old prior to our analyses. Details of each of the variables for the vocational teacher and SLFS subjects appear in Table 1. Table S6 in the Additional file 1 provides a description of the variables.

Methods

First, we compare how much the teachers earned relative to others with the same characteristics in their original occupation. This shows us whether those who choose teaching earn an average, above-average or below-average wage in their former occupation.

Although automatically inferring suitability for teaching from what a person earned in their original occupation is not possible, a somewhat direct relationship nonetheless exists between productivity as measured by earnings in the former occupation and suitability for vocational teaching. This relationship is probably even stronger for vocational teaching than for other teaching categories or occupations. The main task of vocational teachers is to teach young people occupation-specific knowledge relevant to the teacher’s former occupation. Therefore, if we assume that individuals whose skills are above average in their original occupation are more productive and earn commensurately more, then a positive selection should also be beneficial to vocational education.

Our analysis is a form of inversion of that presented by Chingos and West ([2012]), who investigated, of the teachers who left teaching, whether those who earned more in the new occupation had also been the better teachers (i.e., obtained better student performance). Chingos and West ([2012]) identified a positive correlation, which they interpreted to indicate that the same skills that made this group of teachers more productive in the educational system also led to higher wages and therefore higher productivity in other occupations.

We identify a comparison group by matching each teacher with individuals from the SLFS who do not differ from our teachers in terms of key characteristics, such as gender, age, education and occupational field. Because we have a very large pool of non-teaching individuals from the SLFS, we are able to match each teacher with several non-teaching individuals with the same characteristicsg. For each teacher, we estimate a comparable wage in the original occupation by averaging the salaries from SLFS individuals who work in the same occupational field, who hold the same degree of highest education and who are of the same gender and age. These average wages are then compared with the teachers’ wages in their initial occupation (outside education)h. Obviously, our analysis allows us to match only the observable characteristics. However, the individuals might differ in terms of ability, motivation or personality, and it is not within the scope of this study to control for such differences. Therefore, our results have to be interpreted as being the relative wage position of a teacher compared with the average wage of individuals with the same observable characteristics.

If (a) a correlation exists between the occupational abilities and wages in the economy, (b) the hiring authority (usually the head teacher) imputes a correlation between occupational ability and teaching ability, (c) the hiring authority is in a position to choose among different candidates and (d) teaching wages are on average competitive with wages outside education, then teachers who have earned more than comparable colleagues in their initial occupation should be a positive selection into teaching. It is clear that the fourth point, i.e., that teachers’ wages are, on average, competitive with other wages, will not be equally met for all occupations and business sectors because wages vary substantially between sectors but are relatively uniform in teaching, depending on canton, individual’s training, age and experience. We therefore form the hypothesis that individuals have less of an incentive to change to teaching from occupations and industries with average salaries as high as or higher than in teaching. Accordingly, teachers from these occupations and industries would on average be counted among the lower earners in their sector (otherwise teacher pay is not competitive), whereas exactly the opposite would apply in less well-paid occupations and industries. Obviously, there is the possibility that some high performing individuals from high paying industries with wages above the teaching salary change career to teaching and accept a wage cut, for example, because of better working conditions in teaching. However, we expect that, on average, teachers from high paying industries rank among the lower earners in their former occupation.

Second, we investigate the wage prospects of career changers who have opted to become teachers. Teachers can earn more or less as teachers than they would have earned had they decided to stay in their former occupation.

Those who opt to become teachers are unlikely to represent a random sample of all individuals who could theoretically become teachers. Thus, a simple comparison of teachers’ wages with average alternative wages is not a useful way of learning whether the decision to change to teaching pays off financially. This study explores therefore the counterfactual situation to the decision to become a teacher by surveying teacher’s expectations on both options. The questionnaire asked teachers to indicate their wage expectations for two scenarios: first, expected wages (five and 10 years after training) if they stay in teaching and second, expected wages (five and 10 years after training) if they had continued to work in their original occupation.

Whether these wage expectations are indeed accurate ex post is irrelevant to what is at stake here, i.e., the selection to the teaching occupation. What matters are the expectations of individuals who decided to enter teaching at the time they made those decisions (ex ante). In accordance with search and matching models, one expects the average teacher to expect a monetary benefit from the change. A conscious decision to accept a monetary disadvantage from the decision to enter teaching likely occurs only in cases in which the relative non-monetary benefits of teaching are high enough to more than compensate for the monetary disadvantages.

Results and discussion

The results show that teachers represent a positive selection on average, i.e., they earned significantly more in their former occupation than comparable individuals who did not change career to teaching (see Table 2). Teachers earned, on average, 5,497 Swiss Francs (CHF)i more per annum in their former occupation than comparable colleagues (this is some 6% more than the average salary in the control group). The wage advantage over matched individuals is also positive for formerly self-employed individuals (approximately 18% of our sample); however, this estimate is not very precise. This result is no surprise given the high earnings heterogeneity among the self-employed population. The result shows that the decision-making scenario for the formerly self-employed is much more difficult to model than that of former salaried employees. To take these differences into account, we conduct the following analyses separately for each of the two initial employment situations.

In a further analysis, we regressed the individual wage differential (the teacher’s wage in the non-teaching occupation minus the average wage of a comparable colleague in the same occupation) against the various characteristics of the teachers. This analysis shows us which individuals earned more or less in their former occupation than comparison subjects. The results in model 3 (Table 3) show that individuals in senior positions and specific industries earned significantly more than comparison subjects, whereas others earned significantly less. Other characteristics, such as gender or qualifications, have no significant impact on wage differences for an average teacher.

In keeping with the hypotheses outlined earlier, the large effect of sizes for the occupational categories show a consistent picture. The higher the average wage level in an occupation, the more likely that teachers will constitute a negative selection, i.e., those who tend to earn less than comparison subjects, and vice versa. The average wage is about CHF 98,805 in the “engineering and informatics” category and CHF 89,022 in “management, administration, banking, insurance and judiciary”, and the coefficient is negative in both cases.

In contrast, the average wage level in the reference category “industry and manufacturing” is CHF 69,922, and all of the occupation categories that deviate positively from the reference category feature average wages in the under CHF 80,000 range. This finding demonstrates that average salaries in the former occupation are the main factor determining whether teachers are more likely to constitute a positive or negative selection from their occupational sector in terms of earnings.

Model 4 shows that individuals with an upper secondary qualification and advanced occupation-specific qualification (ISCED 5B) constitute an average selection, whereas, for individuals with an academic qualification, positive selection applies only to those who did not previously have the option of working part-time. In contrast, subjects with an academic qualification who also had the option of working part-time are among those who earned significantly less than the comparison group in their former occupation.

The position in the wage distribution in the initial occupation of teachers does not tell us whether the career change into teaching pays off. To analyze this, we calculate the differences between wage expectations for teaching and original occupation by eliciting the respective expectations in the teacher surveyj. The results show that the average teacher expects an annual wage benefit in teaching compared with the former occupation. This difference is significantly different from zero. However, individual results with respect to relative wage expectations can be both positive and negative. Depending on the scenario, between one-quarter and one-third of teachers expect to earn less than in their original occupation (see Table 4).

A regression of this expected wage difference on teacher characteristicsk reveals that, for all scenarios, teachers with an academic tertiary A education expect to gain significantly less from a change to teaching than teachers with another educational background. The same applies for teachers from occupations in management, administration, banking, insurance and law, one of the industries with the highest wage level. Furthermore, teachers who hold a senior position in their former occupation also expect a significantly lower wage difference. Finally, tenure is negatively correlated with the expected wage difference.

Conclusion

This study investigates the determinants of career change for individuals who change jobs to become a teacher as a second career. This paper focuses mainly on the relevance of monetary factors in making people more or less likely to decide in favor of changing careers to teaching, as monetary factors are one of the most discussed levers for Swiss educational policy makers to influence the equilibrium of supply and demand in the labor market for teachers. However, an analysis of monetary factors allows us also to draw conclusions with respect to the relative importance of non-monetary factors (e.g. time off, workloads, fringe benefits, etc.) in informing the individual decision to change careers to teaching.

The framework for this study is the Swiss vocational education system, which requires that teachers of vocational subjects have a prior career in that specific field and, therefore, vocational teachers are all career changers.

The finding that the average teacher earned significantly more in his or her former occupation than comparison subjects supports the appeal for teaching. This result indicates that the average career changer does not change careers because he or she is (financially) unsuccessful or unproductive in their original occupation. Because a positive correlation between productivity in the original occupation and aptitude for teaching in vocational teaching is likely, this result has positive implications for the quality of vocational schools.

As to recruitment chances of vocational schools in the individual occupations: the higher the average wage level in an occupation, the larger the probability that individuals recruited from that occupation will rank among the low earners. Teachers need to be recruited from sectors of the rest of the economy with extremely different wage levels, but there is no major wage differential in the educational system. Therefore, as a function of wage level in the economy, equally “talented” teachers will not be available for all of the occupations taught in the VET system.

The results for all of the analyses display significant heterogeneity, some of which can be explained. Positive selection for individuals with a university degree applies only to those individuals (largely male) who did not have the option of working part-time in their former occupation, whereas the other teachers with a university degree constitute a negative selection in terms of their relative earnings in their former occupations. This analysis shows the great relevance of non-monetary factors (e.g., flexibility to arrange individual working time) in forming the decision to enter teaching. Therefore, the recently started discussion in Switzerland about highlighting non-monetary benefits in the public perception in order to attract scarce candidates can be seen as a fine step forward to improve the appeal of teaching jobs.

Although the average teacher tends to rank among the better earners in his or her original occupation, the majority of career changers expect to earn more as a teacher than in their original occupation. This finding shows that the average wage level at vocational schools can compete with average wage levels in the rest of the economy. Again, however, substantial heterogeneity exists given that between one-quarter and one-third of career changers are prepared to accept a cut in wage after changing to teaching. One probable explanation is the very high relevance of non-monetary factors that make teaching a more attractive option, at least for some individuals.

Endnotes

aGerman and French-speaking Switzerland accounts for more than 95% of the Swiss population.

bThis implies the assumption that wage in the former occupation is positively correlated with productivity in the former occupation and commensurately also in teaching.

cTertiary level B professional education and training (PET) consists of the Federal PET Diploma Examination, the Advanced Federal PET Diploma (also referred to as Meisterprüfung) and PET Colleges (SKBF [2010]). Professional (occupational) college programs last two to three years full- or part-time, the duration of the Federal PET Diploma Examination and Advanced Federal PET Diploma is unspecified as attendance of the preparation courses is not compulsory. However, they require a certain number of years’ work experience in the relevant occupation.

dHowever, the sample also contains some teachers whose highest previous educational qualification was only upper secondary education (8%). Either these teachers come from professions with no tertiary education programs, or the vocational school recruited the teachers despite their low academic qualifications because of a shortage of teachers in a particular field.

eResults are available from the authors on demand.

fWhether movers from other occupations had quit or had been laid off may have a substantial impact on selection into teaching jobs. However, only 6% of the career changers were involuntarily unemployed within three years before changing to teaching and the expected wage gains/losses from career change do not differ significantly between the two groups.

gTherefore, we use exact matching (see Abadie et al. [2004]).

hThe matching strategy is similar to an approach where residuals from a wage regression (for SLFS individuals and teachers) would be examined and actual wages and predicted wages would be compared with see whether teachers earned more or less than their peers (predicted wage) in their original occupation. The advantage of the matching strategy is that no assumptions about the functional form of the wage regression are imposed.

iAt the time of the study one Swiss Franc (CHF) was roughly equivalent to 1.45 Euro (EUR).

jDescriptive statistics on wage expectation can be found in Additional file 1, Table S7.

kResults are available from the authors upon request.

Additional file

References

Abadie A, Herr JL, Imbens GW, Drukker DM (2004) NNMATCH: Stata Module to Compute Nearest-Neighbor Bias-Corrected Estimators. Statistical Software Components, Boston College Department of Economics. , [http://fmwww.bc.edu/repec/bocode/n/nnmatch.ado]

Altonjii JG, Paxson CHH: Job Characteristics and Hours of Work. In Research in Labor Economics, 8 (Part A). Edited by: Ehrenberg RG. Westview Press, Greenwich; 1986:1–55.

Atrostic BK: The demand for leisure and nonpecuniary Job characteristics. Am Econ Rev 1982, 72(3):428–440.

Becker GS: Investment in human capital: a theoretical analysis. J Polit Econ 1962, 70: 9–49. 10.1086/258724

Burdett K: A theory of employee job search and quit rates. Am Econ Rev 1978, 68: 212–220.

Chevalier A, Dolton P, Mcintosh S: Recruiting and retaining teachers in the UK: An analysis of graduate occupation choice from the 1960s to the 1990s. Economica 2007, 74: 69–96. 10.1111/j.1468-0335.2006.00528.x

Chingos MM, West MR: Do more effective teachers earn more outside of education? Educ Finance Policy 2012, 7(1):8–43. 10.1162/EDFP_a_00052

Clark AE: What really matters in a job? Hedonic measurement using quit data. Labor Econ 2001, 8(2):223–242. 10.1016/S0927-5371(01)00031-8

Corman H: Who will teach? Policies that matter: Richard J. Murnane, Judith D. Singer, John B. Willett, James J. Kemple and Randall J. Olsen. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991. xii + 187 pp. Econ Educ Rev 1993, 12: 273–274. 10.1016/0272-7757(93)90013-7

Cornelissen T: The interaction of Job satisfaction, Job search, and Job changes. An empirical investigation with German panel data. J Happiness Stud 2009, 10: 367–384. 10.1007/s10902-008-9094-5

Daniel K, Heywood JS: The determinants of hiring older workers: UK evidence. Labor Econ 2007, 14: 35–51. 10.1016/j.labeco.2005.05.009

Denzler S, Wolter SC: Sorting into teacher education: how the institutional setting matters. Camb J Educ 2009, 39: 423–441. 10.1080/03057640903352440

Doeringer PB, Piore MJ: Internal Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis. DC Heath, Lexingtion, MA; 1971.

Dolton PJ: The economics of UK teacher supply: The graduate’s decision. Econ J 1990, 100: 91–104. 10.2307/2234187

Dolton PJ, Chung T-P: The rate of return to teaching: How does it compare to other graduate jobs? Natl Inst Econ Rev 2004, 190: 89–103. 10.1177/002795010419000109

Falch T: The elasticity of labor supply at the establishment level. J Labor Econ 2010, 28: 237–266. 10.1086/649905

Geel R, Mure J, Backes-Gellner U: Specificity of occupational training and occupational mobility: an empirical study based on Lazear’s skill-weights approach. Educ Econ 2010, 19(5):519–535. 10.1080/09645291003726483

Hanushek EA, Pace RR: Who chooses to teach (and why)? Econ Educ Rev 1995, 14: 101–117. 10.1016/0272-7757(95)90392-L

Heywood J, Jirjahn U, Tsertsvardze G: Hiring older workers and employing older workers: German evidence. J Popul Econ 2010, 23: 595–615. 10.1007/s00148-008-0214-7

Jovanovic B: Job matching and the theory of turnover. J Polit Econ 1979, 87: 972–990. 10.1086/260808

Kunze L, Suppa N: Job Characteristics and Labour Supply , Ruhr Economic Papers, No. 418. 2013.

Lazear EP: Why is there mandatory retirement? J Polit Econ 1979, 87(6):1261–1284. 10.1086/260835

Lazear EP: Agency, earnings profiles, productivy, and hours restrictions. Am Econ Rev 1981, 71(4):606–620.

Lazear EP: Firm-specific human capital: a skill-weights approach. J Polit Econ 2009, 117: 914–940. 10.1086/648671

Lüchinger S, Meier S, Stutzer A: Why does unemployment hurt the employed? evidence from the life satisfaction Gap between the public and the private sector. J Hum Resour 2010, 45(4):998–1045. 10.1353/jhr.2010.0024

Manski CF: Academic ability, earnings, and the decision to become a teacher: Evidence from the national longitudinal study of the high school class of 1972, Public Sector Payrolls. NBER Chapters, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc, MA, USA; 1987.

Mortensen DT: Job search and labor market analysis, in Handbook of Labor Economics. Elsevier North-Holland, Amsterdam; 1986.

Neal D: The complexity of job mobility among young men. J Labor Econ 1999, 17: 237–261. 10.1086/209919

Podgursky M, Monroe R, Watson D: The academic quality of public school teachers: an analysis of entry and exit behavior. Econ Educ Rev 2004, 23: 507–518. 10.1016/j.econedurev.2004.01.005

Rubinstein Y, Weiss Y: Post Schooling Wage Growth: Investment, Search and Learning, in Handbook of the Economics of Education, Vol. 1. Elsevier North-Holland, Amsterdam; 2006.

Swiss Education Report 2010. SKBF, Aarau; 2010.

Stinebrickner TR: A dynamic model of teacher labor supply. J Labor Econ 2001, 19: 196–230. 10.1086/209984

Wells R: An examination of the utility bearing characteristics of occupations: A factor analytical approach. Econ Lett 2010, 108: 296–298. 10.1016/j.econlet.2010.05.007

Wolter SC, Denzler S: Wage elasticity of the teacher supply in Switzerland. Brussels Econ Rev 2004, 47: 387–408.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Stefan C. Wolter for setting up the project and Jean-Louis Berger and co-workers at the Swiss Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (SFIVET) for their cooperation in generating the data. The authors also wish to express their thanks for the funding supplied by the State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) and the Swiss Leading House “Economics of Education” of the Universities of Zurich and Bern. The authors thank the editor, Kerstin Pull, and two referees for the valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SH and MSL carried out the analysis and wrote the article. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hof, S., Strupler Leiser, M. Teaching in vocational education as a second career. Empirical Res Voc Ed Train 6, 8 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-014-0008-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-014-0008-y