Abstract

In Switzerland, access to non-academic occupations requires the completion of a vocational education and training (VET) program. Over two-thirds of adolescents choose to start a dual VET program after compulsory education. However, this path from school to work is not always linear, and changes can be a means of adjusting wrong career choices. In the context of dual VET, two types of adjustments that occur frequently can be distinguished: (1) change of occupations and (2) change of companies. The present study aims to examine the predictors of each of those two types of changes. First, we are interested in the link between individuals’ intentions to change their career paths and actual changes. When changes are intended by the trainee and aimed at correcting wrong career choices, actual changes can generally be expected to be predicted by change intentions. Second, we are interested in the role of person-job fit (P-J fit) as well as trainees’ socialization and performance indicators. Third, we examine to what extent trainees’ decisions to change occupations or companies can be predicted by pre-entry factors (perceived P-J fit and effort during compulsory education before the transition to VET). We used a longitudinal sample of adolescents at the end of compulsory school and at the end of their first year in a dual VET program in Switzerland. This data set is combined with government data on actual changes regarding individuals’ training companies and their occupations. The two types of adjustments were examined in separate structural equation models that compared trainees without any types of adjustments during their training program (1) to those who changed occupations (N = 417) and (2) to those who changed training companies (N = 378). The results show that actual occupational changes and actual company changes of trainees are affected by the same work-context predictors (negative effect of trainees’ self-perceived work performance) and pre-entry predictors (negative effect of effort during compulsory education). However, in contrast to changes of training companies, changes of occupations are significantly predicted by trainees’ intentions to change. Moreover, while P-J fit during the VET program is the only direct predictor of trainees’ intentions to change occupations, intentions to change companies are not significantly predicted by P-J fit. Intentions to change companies are negatively affected by companies’ socialization tactics and positively affected by adolescents’ pre-entry effort. Overall, the results call for a more differentiated assessment of changes/ premature contract terminations in future studies. Whether change intentions are a valid proxy for actual change behavior seems to depend on the type of changes that trainees decide to make.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The transition from compulsory school to work is an important step for adolescents (Buchmann, 1989; Savickas, 1999). In countries with strong vocational education and training (VET) traditions, such as Switzerland, access to non-academic occupations requires the completion of a VET program. In Switzerland, over two-thirds of adolescents enter VET after compulsory education and 80% of them are in dual training programs (SCCRE, 2018). However, transitions from school to work are not always linear. The high rates of premature contract terminations that are regularly reported for VET programs (Switzerland: 22.4%; Federal Statistical Office, 2021) illustrate that discontinuous transition patterns and non-linear pathways into the labor market (critical transitions; Stalder, 2012) are quite common (see e.g., Buchmann, 1989 or Mayer, 2001 on adolescents’ life courses).

Premature contract terminations can certainly be problematic for those individuals who completely drop out of the educational system without having acquired any qualifications (for evidence on long-term effects on the subjective well-being of this group, see Michaelis & Findeisen, in press). However, a more differentiated view on this construct is needed, as different types of premature contract terminations differ both in terms of reasons and consequences for individual trainees (Krötz & Deutscher, 2022; Stalder, 2012). Evidence shows that in the majority of cases individuals re-enter education and training after a contract termination (for Switzerland: 72% [Schmid, 2012; Schmid & Stalder, 2012]; for Germany: 63% [Michaelis & Richter, 2022], 71% [Wydra-Somaggio, 2021]). Hence, for most individuals, premature contract terminations in VET seem to be a means to adjust their career paths. These changes mark discontinuous but not unsuccessful trajectories into the labor market. In fact, trainees who re-enter into a VET program after a premature contract termination report significantly higher educational satisfaction compared to their previous situation; the increase in satisfaction is particularly large for trainees who changed their training company or their training occupation (Schmid, 2012; Schmid & Stalder, 2012). Moreover, the share of adolescents who successfully complete a VET program after a premature contract termination (within seven years after completing compulsory education) varies significantly between different types of trajectories (e.g., 72% for trainees who change companies vs. 40% for trainees who change occupations; Stalder, 2012).

Hence, premature contract terminations that occur as a result of or as a means to change trajectories (e.g., change of occupations or change of training companies) have to be distinguished from dropouts in the narrower sense of the word. However, despite the growing number of studies on reasons for premature contract terminations, studies that distinguish between different types of premature contract terminations are still rare.

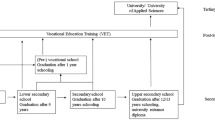

Consequently, this paper aims to examine predictors of different types of premature contract terminations among trainees in dual VET programs. This study is conducted for the context of VET in Switzerland. Switzerland seems to be an interesting example to examine this research question, as for the majority of adolescents the successful completion of a VET program is a prerequisite for the transition to work. Moreover, there is a clear focus on dual VET programs. In Switzerland, adolescents usually start a VET program after completing the 9th grade of compulsory education. VET programs last either two years (Federal Certificate of Vocational Education and Training) or three to four years (Federal Diploma of Vocational Education and Training). They consist of company-based training, in which trainees are involved in daily work processes of the training company, and vocational school training, where trainees acquire more theoretical knowledge in a school-based setting (hence the term dual VET). As the significance of VET and the organization of training programs, as well as the issue of dropout in VET, differ across OECD countries (e.g., Frey et al., 2012), the transferability of these results needs to be examined. However, the assumptions made in this study are not specific to Switzerland and it would be expected that these hold for trainees in other countries as well.

Types of Premature Contract Terminations

While the differentiation of different types of premature contract terminations in studies is still rare, some authors have suggested classifications. Schmid and Stalder (2012) distinguish between four dropout types. The first type describes (1) inter-organizational changes, i.e. trainees continue their training program in the same occupation but in a different training company. Moreover, premature contract terminations can result in (2) downgrading or upgrading. This would mean that trainees start a new VET program within the same occupational field that is intellectually less demanding or more demanding. In these cases, trainees can continue their training without starting over; often they can even stay in the same company (for details see also Schmid, 2012). The third type includes (3) occupational changes, where trainees start a new training program in a different occupational field (or even outside of the dual VET system). This typically also requires changing training companies. All of the types described above result in re-entry into (vocational) education. These have to be distinguished from (4) actual dropouts without re-entry into VET or other forms of education. Similarly, Krötz and Deutscher (2022) classify different dropout directions. They distinguish between two types of horizontal dropouts (i.e. either a change of companies or a change of occupations), upward dropouts (trainees leave VET and enter higher education), and downward dropout (i.e. actual dropouts, where trainees leave VET without obtaining a qualification).

In both classifications, premature contract terminations, where trainees remain in (vocational) education, are distinguished from actual dropouts. Differences between the two conceptualizations arise primarily with regard to the inclusion of upward dropouts in the framework of Krötz and Deutscher (2022), which can be attributed to differences in national contexts. In contrast to Switzerland, a large share of adolescents in Germany start their VET program after acquiring a university entrance qualification, allowing them to easily change from VET to higher education. A second difference lies in the consideration of downgrading and upgrading in the framework of Schmid and Stalder (2012). This results in a further vertical differentiation of the horizontal dropout direction of occupational changes.

It seems obvious to expect differences in reasons for and consequences of premature contract terminations when comparing dropouts to re-entries or upward dropouts to downward dropouts. However, different types of horizontal changes (changing occupations and changing companies) can also be expected to differ in terms of reasons and consequences for individual trainees (Krötz & Deutscher, 2022). A change of occupations is a decision that affects adolescents’ future career. It is to be expected that this decision is mostly initiated by the trainees themselves and requires some sort of planning process. The decision for a new training occupation potentially leads to improved conditions for the trainee (e.g., more suitable career choice, better fit). However, changing occupations usually requires the start of a new training program and is often connected to some sort of waiting period, as most programs only start in summer or fall. A change of training companies could, in contrast, also be initiated by the company; hence, the trainees’ own share in the decision is expected to be lower. As such, this type of change might be related to negative experiences (e.g., experience of failure, low training quality). However, the consequences of company changes are smaller because after changing training companies, trainees could potentially resume their training program without major interruptions.

The number of studies on actual premature contract terminations that systematically distinguish between different types/ directions is still rather scarce. Stalder (2012) finds that trainees with linear transition patterns differ from different types of nonlinear transitions with respect to performance indicators (e.g., grades in vocational school) and perceptions of the training situation (e.g., trainers, work tasks). Moreover, Bessey and Backes-Gellner (2015) show that actual dropouts and revisions of occupational choice (trainees stay in VET after a premature contract termination) are predicted by different factors (e.g., trainees’ financial considerations). Michaelis and Richter (2022) examine different trajectories after trainees’ premature contract terminations. Their results allow for a differentiation between predictors of different types of changes, including re-entries into VET, transitions to higher education, and actual dropouts from VET. However, the analysis does not distinguish between the different types of re-entry into VET (e.g., horizontal changes). Wydra-Somaggio (2021) examines different paths after a premature contract termination and differentiates between trainees who started a new VET program in the same occupation, those who started a new VET program in a different occupation, and those who dropped out of VET. This study reveals that the subsequent path depends on the timing of the premature contract termination: The earlier a contract termination occurs the more likely is the start of a new VET program afterwards. In a recent study, Holtmann and Solga (2023) distinguish between trainees who drop out of VET and those who either change occupations, change companies or enter higher education after a premature contract termination. They are interested in the effects of performance- and integration-related factors. The results show, for instance, that mathematical competence reduces the risk of actually dropping out of VET or of changing occupations. Moreover, trainees who are trained in their desired occupation are less likely to drop out permanently, change occupations, or enroll in higher education.

Change Intentions and Change Behavior

Studies on turnover and dropout often use intentions as an indicator for imminent decisions to change a career path. Hereby, it is generally expected, that intent is a valid predictor of individuals’ behavior. In empirical studies, intentions are often used as a “surrogate variable” (Dalton et al., 1999) since intentions are easier to assess than actual change behavior. However, so far the relationship between intentions and actual changes is empirically unclear. Evidence from higher education points toward a significantly positive effect of dropout intentions on dropout (e.g., Deuer & Wild, 2018; Lent et al., 2016). Regarding turnover (intentions), there is mixed evidence. Turnover intentions are found to be a valid proxy for turnover in some studies (e.g., Sun & Wang, 2017; van Breukelen et al., 2004) or an important mediator (e.g., between integration or job satisfaction and turnover) (Price & Mueller, 1981). Other studies show that turnover intentions and turnover are predicted by different factors (e.g., Cho & Lewis, 2012; Cohen et al., 2016). Evidence from the VET context is still scarce. Existing studies suggest a positive relationship. Fieger (2015) shows for students in Australian VET programs that even when controlling for other predictors (e.g., satisfaction, qualification level), students’ intentions to complete the VET program at the time of enrollment significantly positively predict actual completion. Based on a sample of adolescents in either higher education or VET in Switzerland, Samuel and Burger (2019) find that adolescents’ dropout intentions significantly predict actual dropouts, even when controlling for the individuals’ self-efficacies, negative life events, support etc.

In the VET context, trainees’ intentions to leave are typically assessed by asking them whether they have thought about terminating their training program (e.g., Krötz & Deutscher, 2021; Volodina et al., 2015) or how sure they are that they will complete the training program (e.g., Neuenschwander et al., 2018). The latter conceptualization builds on trainees’ expectations and their (un)certainties about their persistence in the VET program. In general, trainees’ intentions to prematurely terminate their training contract capture the extent to which the decision to leave VET is based on a rational, long-term decision-making process and mirrors trainees’ own contribution to the termination decision. As outlined above, the decision to change occupations is expected to be initiated more often by the trainees than the decision to change companies. Consequently, the relationship between intent and actual change could potentially be different for changes of occupations and changes of companies. However, a distinct assessment of different types of trainees’ intentions to change/ drop out of their VET program has only recently been implemented (Krötz & Deutscher, 2022). Krötz and Deutscher (2022) show that the intentions for different types of premature contract terminations are distinct but correlated constructs (e.g., intentions to change occupations and intentions to change companies: r = 0.478).

Predictors of Changes/ Change Intentions

Rationale for the Selection of Predictors

There is a growing number of studies on reasons for premature contract terminations. The existing evidence shows that there is a whole range of factors to consider when analyzing trainees’ decision to terminate their contract prematurely (a recent meta-synthesis by Böhn & Deutscher, 2022, identified a total of 666 potential reasons for premature contract terminations in VET). Consequently, when examining premature contract terminations, a selection of predictors to be considered is essential. Despite the growing evidence on possible determinants of premature contract terminations, there is still a lack of established theoretical models in this area, which is why we based the selection of predictors on empirical considerations. In this study, we focus on trainees’ perceptions of person-job fit (P-J fit), which is considered a key construct affecting premature contract terminations or career adjustments in VET (e.g., Bosset et al., 2022; Nägele et al., 2017; Neuenschwander, 2011; Stalder, 2012). In addition to the general importance of this construct, fit perceptions are particularly interesting in the context of our study because it seems plausible, that fit perceptions affect different types of premature contract terminations differently (Krötz & Deutscher, 2022; Stalder, 2012).

In addition to trainees’ fit perceptions, we selected four other predictors: training companies’ socialization tactics, trainees’ perceptions of performance, trainees’ anticipated fit, and trainees’ effort. These predictors have been shown to significantly affect premature contract terminations (see the following sections) and represent different categories of crucial dropout determinants: (1) learner factors (performance, effort), (2) company factors (socialization tactics), and (3) professional factors (anticipated fit as an indicator of the career choice process) (see Böhn & Deutscher, 2022). Furthermore, the selected predictors are determinants of or closely related to P-J fit. It is expected that individual pre-entry characteristics of trainees (e.g., skills, effort) affect perceived P-J fit during the training program, since they determine access to desired training occupations and shape trainees’ perception of the work environment (see e.g., Neuenschwander, 2011). After the transition to VET, trainees’ perceptions of fit are affected by the training companies’ integration effort (social aspects of integration) as well as by trainees’ performance during the training program (performance aspects of integration). During the integration process into a new work environment, the company’s support and socialization tactics foster individuals’ perception of P-J fit (Cable & Parsons, 2001; Kristof-Brown et al., 2005; Lent & Brown, 2008; Saks & Gruman, 2011; for the VET context, see, e.g., Neuenschwander & Gerber, 2014; Neuenschwander & Hofmann, 2022). For newcomers, Wang et al. (2011) show that fit perceptions mediate the relationship between the socialization process and turnover intentions. Moreover, trainees will perceive their fit to the training situation to be higher if they are able to perform their work tasks well. Consequently, P-J fit correlates positively with employees’ performance (r = 0.20; Kristof-Brown et al., 2005).

Hence, the present study focuses on five predictors of changes/ change intentions: (1) perceived P-J fit, (2) training companies’ socialization tactics, (3) perceived performance, (4) anticipated P-J fit, and (5) effort. Theoretical considerations and empirical evidence regarding the relevance of each predictor of changes/ change intentions are reported in the following sections. It remains to be examined, to what extent the role of these five predictors varies for different types of premature contract terminations.

Perceived P-J Fit

When entering a VET program, adolescents are faced with the task of adjusting to their new environment, integrating into the organization/ the working group and to learn to successfully complete their work assignments (Bauer & Erdogan, 2011). One aspect of integration is individuals’ perception of fit to the new context (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). P-J fit refers to the congruence between individual trainees and their training situation, both with regard to trainees’ skills and abilities and with regard to trainees’ needs and preferences (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). The transition from school to VET is expected to be easier if trainees enter a training situation that is a good fit for them (e.g., Nägele & Neuenschwander, 2015). Fit is regarded to be a dynamic construct, and if an individual perceives their training situation to be a good fit, it seems plausible that they would choose to stay in this training situation and would feel determined to follow through with the chosen career path and to complete the training program (Spady, 1971; Stalder, 2012; Swanson & Fouad, 1999). Accordingly, empirical evidence speaks in favor of a positive relationship between fit and persistence (intention). Employees’ P-J fit has been shown to be negatively correlated with intent to quit (r = -0.46; Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). A meta-analysis of turnover research reveals that perceived fit leads to lower turnover (intentions) (van Iddekinge et al., 2011). For trainees in VET, the perceived P-J fit positively predicts persistence intentions (Findeisen et al., 2022; Volodina et al., 2015). Moreover, Bosset et al. (2022) find that trainees who stay in the VET program report significantly higher fit perceptions than trainees who leave the VET program. Accordingly, evidence shows that attending a training program in the occupation desired by the trainee decreases the likelihood of a premature termination of the VET program (Beicht & Ulrich, 2008; Beicht & Walden, 2013; Michaelis & Richter, 2022). When examining different types of changes, being trained in the desired occupation is shown to negatively predict trainees’ decision to change occupations, but not their decision to change training companies (for actual changes see Holtmann & Solga, 2023; for dropout intentions see Krötz & Deutscher, 2022. Consequently, when examining predictors of premature contract terminations in VET—and especially when interested in changes of occupations and changes of training companies—P-J fit is one central concept to consider.

Socialization Tactics

During the process of organizational socialization (or onboarding), newcomers “learn the knowledge, skills, and behaviors they need to succeed in their new organizations” (Bauer & Erdogan, 2011, p. 51). As part of organizational socialization, a company’s socialization tactics are expected to facilitate newcomers’ adjustment to the organization and to the new job (Bauer et al., 2007). In the context of VET, adolescents enter a work environment at a rather young age. In this context, it seems particularly important that trainees obtain comprehensive support and that they are received by welcoming socialization tactics of the training company. The results of Bauer et al. (2007) reveal that organizational socialization tactics directly predict newcomers’ intentions to remain and indirectly predict newcomers’ turnover. For the context of VET, Krötz and Deutscher (2022) show that indicators of training quality relating to support for trainees (namely feedback and mentoring) predict trainees’ intentions to change the training company, however, not trainees’ intentions to change occupations, to drop out or to pursue higher education. In contrast, trainees’ perceived social involvement with the group of co-workers affects all types of intentions for premature contract terminations but in particular changes of occupations and changes of companies. Bosset et al. (2022) show that leavers and stayers in VET differ significantly regarding their perception of support by trainers.

Perceived Performance

Another relevant predictor of persistence is trainees’ performance. For newcomers, empirical evidence shows that task mastery is linked to lower turnover intentions (Kammeyer-Mueller & Wanberg, 2003). In the VET context, premature contract terminations have been related to trainees’ poor performance (see the meta-synthesis of Böhn & Deutscher, 2022). Comparing the means of VET “stayers” and “leavers”, Bosset et al. (2022) find significant differences for the performance in vocational schools, but not for the performance in the company. However, in an additional interview study, trainees report performance in both vocational schools and the company as reasons for premature contract terminations (Bosset et al., 2022). Regarding different types of premature contract terminations, performance is expected to be especially relevant for trainees’ decisions to change occupations. If a trainee is ill-equipped to fulfill the work tasks in their occupation, they are expected to be less determined to complete the current training program and are more likely to consider changing career paths (see e.g., Holtmann & Solga, 2023 for mathematical competence). Accordingly, when examining different types of adjustments, Krötz and Deutscher (2022) show that training performance is linked to occupational change intention, but none of the other types of termination intentions.

Anticipated P-J Fit

The entry process into VET is predetermined by both motivational factors as well as factors of the occupational choice process prior to entry into the VET program, i.e., at the end of compulsory education. One indicator that is commonly used as an outcome of adolescents’ occupational choice processes is anticipated person-environment fit (Hirschi, 2011). Pre-entry fit is expected to facilitate the integration process into the VET program (Nägele & Neuenschwander, 2014; Saks & Ashforth, 2002). As such, anticipated fit is also assumed to positively affect trainees’ performance in VET as well as their perception of the training company’s socialization tactics. Since anticipated fit has been shown to predict perceived fit during the VET program (e.g., Findeisen et al., 2022; Neuenschwander & Hofmann, 2022), indirect effects on trainees’ change (intentions) can be expected as well (see also Findeisen et al., 2022).

Effort

Trainees’ effort upon entry into the VET program is expected to affect their work performance but also foster their perception of the company’s socialization tactics and promote proactive behavior of trainees that supports socialization processes (see e.g., Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). In addition, trainees with high effort motivate the collaborators in the company to welcome them and to give better feedback. Consequently, effort is expected to affect P-J fit (see above) and, hence, indirectly trainees’ change (intention). Adolescents who are in work or school contexts that address their needs are motivated to work hard, feel happier, and have weaker intentions to leave (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). Accordingly, effort plays a major role in predicting high school dropouts (Englund et al., 2008; Janosz et al., 2008). For effort in vocational schools during VET programs, Bosset et al. (2022) find significantly higher values for trainees without premature contract terminations compared to trainees leaving the VET program. According to the result of Kemmler (2012), achievement motivation plays a significant role in predicting trainees’ dropout intention. Moreover, a lack of effort in the work as well as the school context is among the most mentioned reasons for premature contract terminations reported by both trainees and trainers (Stalder & Schmid, 2006). Against this background, effects of pre-entry effort on change (intentions) can also be expected.

The Present Study

The present study aims to examine predictors of different types of premature contract terminations in dual VET programs in Switzerland. We focus on two types of horizontal changes (1: changing occupations and 2: changing companies) and we are especially interested in analyzing whether these are equally affected by different predictors. We use longitudinal data on Swiss trainees in dual VET programs, including two measurement points during their educational paths: (1) before adolescents’ transition to the work context (pre-entry) and (2) at the end of their first year into a VET program. This data is then matched with official data from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (FSO) on adolescents’ further courses of training.

We add to the existing literature in the following ways. First, we relied on data on actual changes, while prior studies often examined individuals’ intentions to change their situation. Hence, our results also provide insights into the link between intentions and actual change behavior thus help in understanding to what extent the different types of premature contract terminations are intended or planned by trainees. Second, we use longitudinal data, allowing us to examine predictors of both individuals’ situations in general education (before the transition) and their situations after starting the VET program (first year of VET program). While reasons for premature contract terminations are often based on retrospective reports by trainees, we aim to examine which predictors are actually significant over the course of the training program. Third, and most importantly, this study is, to our knowledge, among the first studies to distinguish different types of horizontal changes in VET. Since the decisions to change occupations and to change companies are very different in terms of individuals’ reasons and potential consequences, it is crucial to examine to what extent these types of non-linear pathways are predicted by similar factors. Results on predictors that affect trainees’ changes of occupations and changes of training companies, respectively, are highly relevant in supporting adolescents in their processes of occupational choice and work adjustment. A more nuanced analysis of the predictors of different types of changes will allow training companies to provide more tailored support and guidance for individual difficulties and in the case of change intentions during dual VET programs. Career counselors could also benefit from a better understanding of trainees’ choice processes and their predictors, for instance to inform young adults about potential problems or alternative pathways.

Based on the theoretical assumptions and empirical evidence reported in the previous section, we expect the relationships depicted in Fig. 1. As empirical evidence on differences regarding predictors of the two types of changes examined is still scarce, we decided to analyze the same hypothesized relationships for changes of occupations and for changes of companies in two separate analyses.

Generally, changes/ change intentions are, first, expected to be affected by predictors of the VET context, namely by perceived fit (Bosset et al., 2022; Findeisen et al., 2022; Michaelis & Richter, 2022; Volodina et al., 2015), welcoming socialization tactics (Bosset et al., 2022; Krötz & Deutscher, 2022), and perceived work performance (Böhn & Deutscher, 2022; Bosset et al., 2022; Krötz & Deutscher, 2022). Second, changes/ change intentions can be expected to be affected by pre-entry predictors of occupational choice (anticipated P-J fit; Findeisen et al., 2022) and effort (Bosset et al., 2022; Kemmler, 2012; Stalder & Schmid, 2006). We expect that these postulated relationships hold for both actual changes (H1) and change intentions (H2).

-

(H1) Actual changes are directly and negatively affected by both predictors of the work context (a: perceived P-J fit, b: welcoming socialization tactics by the company, c: perceived work performance) and pre-entry predictors (d: effort in compulsory education).

-

(H2) Trainees’ change intentions are directly and negatively affected by both predictors of the work context (a: perceived P-J fit, b: welcoming socialization tactics by the company, c: perceived work performance) and pre-entry predictors (d: effort in compulsory education).

On the right-hand side of the model (Fig. 1), we distinguish between trainees’ change intentions and actual changes. In dropout research, it is often assumed that dropout intentions are a valid predictor of actual dropout (see section “Change Intentions and Change Behavior”), and existing evidence generally suggests a positive relationship (for the VET context, see e.g., Fieger, 2015; Samuel & Burger, 2019). In line with this, we expect change intentions to positively affect actual changes in career paths (H3). The results on this relationship will provide greater insights into the extent to which the decision to leave VET is based on a rational, long-term decision-making process and mirrors trainees’ own contribution to the termination decision. As argued above, for changes of companies, we expect trainees’ own share in the decision to be lower, as premature contract terminations in this case are often initiated by companies. Hence, our study allows us to examine whether the relationship is comparable in direction and size for the different types of changes occurring.

-

(H3) Trainees’ change intentions positively predict actual changes.

Since we expect a significant effect of intentions on actual changes (Deuer & Wild, 2018; Fieger, 2015; Lent et al., 2016; Samuel & Burger, 2019), it is plausible to also assume additional indirect effects of the examined predictors on actual changes via change intentions (H4a – H4e; see e.g., Bauer et al., 2007). Moreover, based on the importance of trainees’ fit perceptions, indirect effects of both work-context predictors (Cable & Parsons, 2001; Kristof-Brown et al., 2005; Neuenschwander & Hofmann, 2022) and pre-entry predictors (Neuenschwander, 2011) on change intentions via P-J fit seem also plausible (H5a – H5d; see also Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000; Wang et al., 2011).

-

(H4) Actual changes are indirectly and negatively affected by both predictors of the work context (a: perceived P-J fit, b: perceived work performance, c: welcoming socialization tactics by the company) and pre-entry predictors (d: effort in compulsory education, e: anticipated P-J fit) via change intentions.

-

(H5) Trainees’ change intentions are indirectly and negatively affected by both predictors of the work context (a: perceived work performance, b: welcoming socialization tactics by the company) and pre-entry predictors (c: effort in compulsory education, d: anticipated P-J fit) via perceived P-J fit.

Methods

Participants

To test the hypotheses, data from the project "Effects of Tracking" (https://en.wisel-studie.ch/) were used. In this longitudinal study, consisting of six waves, adolescents from four Swiss cantons (Basel, Berne, Lucerne, Zurich) were asked to fill out questionnaires at multiple points in their academic careers. The questionnaires consisted of questions concerning adolescents’ educational paths and attitudes. In this study, we used data from Waves 4 and 5. Wave 4 was conducted in spring 2016, when adolescents were in their last year of lower secondary education (9th grade; ISCED 2), with N = 2376 participants. N = 893 had already participated in one of the three previous waves. N = 1483 resulted from a supplementary sample: all school administrations of schools not yet participating in the four mentioned cantons were asked to participate. Wave 5 was conducted exactly one year later, in spring 2017, when adolescents were in their first year of upper secondary education (ISCED 3). All participants of Wave 4 were contacted, and N = 808 adolescents participated. The survey for Wave 5 occurred about seven to eleven months after trainees started their VET program. For our analysis, we first selected those adolescents who entered dual VET and either participated in Wave 5 or experienced a premature contract termination (N = 498; 48.2% female; age: M = 16.4, SD = 0.67). Of those 498 adolescents, 134 did not participate in Wave 5 (26.9%). However, t-tests conducted for the Wave-4 variables did not reveal significant differences between these two groups, except for effort. Adolescents who participated in Wave 5 showed significantly higher effort during Wave 4 (M = 4.31, SD = 0.92) than adolescents who did not participate in Wave 5 (M = 3.93, SD = 0.95; t(496) = -4.09, p < 0.001, d = 0.41).

Procedures

Adolescents filled out online questionnaires during school (T1) or at home (T2). At T1, teachers supervised the survey after receiving a detailed manual. Adolescents who were not at school during the survey answered the questions at home, either via an online link or using a printed version. At T2, participants received a personalized password to access the online survey. Members of the research team called all participants who had not completed the questionnaire after 10 days. Participants received an unconditional incentive prior to T2. All questionnaires met ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained. Surveyed adolescents explicitly and voluntarily agreed to participate. The use of the data provided by the FSO was subject to strong data protection requirements, which were all met.

Instruments

Types of Premature Contract Terminations/ Changes

To analyze the different kinds of premature contract terminations, we used data provided by the FSO as part of Wave 6, conducted five years after graduating from lower secondary education. Training companies are obliged to report formal terminations of apprenticeship contracts to the FSO. The FSO kindly made this data available to us so that we could match it with the information we collected in our surveys. This way, we know whether participants from Wave 4 terminated their training contract between Wave 4 and 6 years thereafter. For each individual, we checked the data for all types of contract terminations that occurred at some point between the first and final years of VET. In case of multiple contract terminations, individuals were categorized based on the first premature contract termination that occurred.

We categorized individuals into four distinct groups: (a) adolescents with no contract termination, (b) adolescents with one or more terminations who were still completing an apprenticeship in the same occupation, albeit in a different company, (c) adolescents who changed their occupation and started a new VET program in a different field of work, and d) adolescents who did not report an occupation two years after contract termination (dropouts). Due to the small sample size, we neither distinguished occupational changes (group c) further regarding downgrades or upgrades in occupational changes (see Schmid & Stalder, 2012) nor regarding to whether the new training program is attended at the same training company or a different one.

To test our hypotheses, we examined the two types of changes separately against the group of trainees without a premature contract termination. We therefore defined two subsamples. Subsample 1 consisted of all adolescents who either did not terminate their contracts or who terminated their contracts and changed companies (a and b, N = 378, 49.3% female, age: M = 16.4, SD = 0.66). Subsample 2 consisted of all adolescents who either did not terminate their contracts or who terminated their contracts and changed occupations (a and c, N = 417, 50.0% female, age: M = 16.4, SD = 0.66).

Anticipated and Perceived P-J Fit

P-J fit perceptions were assessed at two measurement points: once during T1 and a second time during T2. The same scale consisting of five items by Nägele and Neuenschwander (2014) was used both times. At T1, the items were aimed at the upcoming apprenticeship (anticipated P-J fit), while at T2, they referred to the current situation (perceived P-J fit) (e.g., “My future apprenticeship/ my current situation matches my interests”). The response rate ranged from 1 (not true at all) to 6 (totally true) (Subsample 1: α = 0.84, M = 5.32, SD = 0.63; Subsample 2: α = 0.84, M = 5.31, SD = 0.63).

Socialization Tactics

Socialization tactics of the training company were assessed for the first four weeks of the adolescents’ apprenticeships with four items by Neuenschwander et al. (2013), modified from Cable and Parsons (2001) and Takeuchi and Takeuchi (2009) (e.g., “I felt welcomed in the training company”). The response categories ranged from 1 (not true at all) to 6 (totally true) (Subsample 1: α = 0.81, M = 4.99, SD = 0.87; Subsample 2: α = 0.80, M = 5.00, SD = 0.86).

Perceived Performance

Adolescents’ perceptions of their work performance were assessed with one item (“Overall, how do you rate your current performance in the training company?”) by Neuenschwander et al. (2018). The response categories ranged from 1 (not good at all) to 6 (very good) (Subsample 1: M = 4.99, SD = 0.87; Subsample 2: M = 5.00, SD = 0.86).

Effort

Effort in lower secondary school was assessed with four items (e.g., “I am really hardworking at school”), adopted from Neuenschwander et al. (2013). The response categories ranged from 1 (not true at all) to 6 (totally true) (Subsample 1: α = 0.89, M = 4.28, SD = 0.92; Subsample 2: α = 0.88, M = 4.29, SD = 0.92).

Intention to Change

Adolescents’ intentions to change their training company were assessed with one item (“How likely is it that you will complete an apprenticeship but change training companies during the process?”) by Neuenschwander et al. (2018). The response rate ranged from 0 to 100%. We dichotomized the item via median split, and labeled all adolescents who reported a probability higher than 16% as “higher” since the distribution was not normal.

Adolescents’ intentions to change their occupation were also assessed analogously with one item (“How likely is it that you will complete an apprenticeship but change occupations during the process?”) by Neuenschwander et al. (2018). In this case, adolescents who reported a probability higher than 19% were labeled as “higher” since the distribution was also not normal.

Although we recognize that single-item measures may come with methodological limitations, they might be applied in cases where a single-item measure seems to suffice in obtaining a valid reflection of the construct of interest (see Allen et al., 2022; on the discussion on single-item measures, see e.g., Bergkvist, 2015; Diamantopoulos et al., 2012). We decided on single-item measures for the two types of change intentions as the information on types of changes are very specific, and in our opinion, no additional information is to be gained from rephrasing the question on specific types of change intentions in several items. Single-item assessments of (different types of) change intentions have also been used in prior studies in the field of VET (e.g., Krötz & Deutscher, 2022; Maué et al., 2023). When it comes to adolescents’ perceptions of their own work performance, it may be an advantage to cover a broader range of perceptions (e.g., of different work tasks) with several items. However, since the participants in our survey were rather inexperienced in their VET program at the time of Wave 5, we decided to use a general assessment based on a single-item measure.

Analytical Procedures

For both subsamples, a structural equation model (SEM) was calculated. In the first SEM (Model 1), the dependent variable was the change of one’s training company (1 = yes; 0 = no). All adolescents who either did not terminate their apprenticeship contracts or who changed their training companies (Subsample 1) were included in this analysis. The second SEM (Model 2) focused on the change of occupations. Here, adolescents who either did not terminate their apprenticeship contracts or who reported a change of occupations (Subsample 2) were included. To analyze missing values, Little’s (1988) test was conducted using SPSS (version 28). It did not produce significant results for any of the used variables, which means all missing values were completely at random.

Both SEMs were tested using Mplus 8.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). We controlled for longitudinal metric invariance between the waves of measurement for P-J fit.

The χ2 statistics, comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residuals (SRMR) were used as indicators for model fit. As large samples often lead to significant χ2 values, we based our decision on the other criteria. A CFI value greater than or equal to 0.90 indicates an acceptable fit (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). As for the RMSEA and SRMR, values lower than or equal to 0.08 and 0.10, respectively, are considered indications of an acceptable fit (Schermelleh-Engel et al., 2003). The SEM were modified when the indices’ values did not meet these criteria. Metric invariances for differences between measurement points were tested using the Satorra-Bentler Scaled Chi Square test. All results, except correlations, were reported with one-tailed p-values.

Results

Descriptive Results

Table 1 shows the distribution parameters for all constructs of interest, and the correlations between the constructs are reported in Table 2. Generally, based on the information provided by the FSO, we distinguished trainees into four distinct groups (see Table 1): (1) trainees who did not prematurely terminate their training contracts in the examined period of time (no changes) and trainees who prematurely terminated their training contract and continued a training program in (2) a different occupation (change of occupations), or (3) a different training company (change of companies), or (4) did not enter another training program within three years after contract termination (dropout). Unfortunately, the group of dropouts is too small (see Table 1) to examine predictors of dropout (intention) for this group as well. Consequently, the analysis was based on a comparison of trainees without premature contract terminations and (1) trainees changing their occupation (see section “Predictors of Occupational Changes”) and (2) trainees changing their training company (see section “Predictors of Company Changes”).

Predictors of Occupational Changes

Figure 2 shows the SEM comparing trainees who changed occupations to trainees who did not terminate their training contract; hence, the model examines predictors of occupational changes. The model explains 25% of the variance in trainees’ actual changes and 19% of the variance in trainees’ intentions to change occupations. As the results reveal, actual changes of occupations are significantly negatively predicted by trainees’ self-perceived work performance during VET as well as by effort during compulsory education (supporting H1c and H1d). Against expectations, however, trainees’ perceived P-J fit and companies’ socialization tactics do not significantly affect actual occupational changes (H1a and H1b are rejected).

Path coefficients of the structural equation analysis on occupational changes (N = 417). Note. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05. Standardized path coefficients. Model fit: χ2 = 191.71, df = 132, p < .001, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .04. To increase readability, the measurement model of the latent constructs is omitted from this figure. Non-significant paths are depicted in gray

Regarding trainees’ intentions to change occupations, the results revealed a significant negative effect of P-J fit, which is consistent with expectations (H2a). Against hypotheses H2b–H2d, none of the other predictors (perceived work performance, welcoming socialization tactics, and effort) affected trainees’ intentions to change their occupation. Moreover, actual changes of occupations were significantly positively predicted by trainees’ change intentions, which is consistent with H3.

In addition to the direct effects, we examined the indirect effects on both actual occupational changes and change intentions. In contrast to H4a–H4e, none of the hypothesized indirect effects on actual occupational changes via change intentions proved to be significant (see Table 3). Hence, neither predictors of the work contexts nor pre-entry predictors significantly indirectly predicted actual changes via change intentions. However, we did find indirect effects on change intentions via perceived P-J fit in T2 (see Table 4). The results revealed significant indirect effects of both perceived work performance (T2) and welcoming socialization tactics (T2) on trainees’ change intentions via perceived P-J fit (T2) (supporting H5a and H5b). In line with H5c, we found different significant paths describing the indirect effects of trainees’ pre-entry efforts on change intentions via P-J fit. Moreover, there were indirect effects of anticipated P-J fit in T1 on change intentions via perceived P-J fit in T2 (supporting H5d).

Predictors of Company Changes

The model examining predictors of the second type of premature contract terminations, changes of training companies, is depicted in Fig. 3. In this model, trainees who changed training companies are compared to trainees who did not experience a premature contract termination. The explained variance was similar to that of the model on occupational changes (R2 = 0.17 for intentions to change companies and R2 = 0.25 for actual company changes). Regarding predictors of actual company changes, we also found analog effects compared to the model on occupational changes: Company changes were significantly negatively predicted by self-perceived work performance during VET and effort during compulsory school (supporting H1c and H1d), while trainees’ perceived P-J fit and companies’ socialization tactics did not affect company changes (contradicting H1a and H1b).

Path coefficients of the structural equation analysis on company changes (N = 378). Note. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05. Standardized path coefficients. Model fit: χ2 = 238.09, df = 132, p < .001, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .05. To increase readability, the measurement model of the latent constructs is omitted from this figure. Non-significant paths are depicted in gray

When it comes to predictors of trainees’ intentions to change companies, the model indicated a significantly negative effect of companies’ welcoming socialization tactics, which was consistent with expectations (H2c). However, contrary to H2a and H2b, perceived P-J fit and perceived work performance did not significantly affect trainees’ intentions to change companies. Moreover, adolescents’ effort at the end of compulsory education had a positive effect on trainees’ intentions to change their training companies. This contradicted H2d as we expected a negative effect. Furthermore, unlike for occupational changes (see the previous section), there was no significant relationship between intentions and actual changes of training companies (contrary to H3).

The analysis of indirect effects revealed that—contrary to H4a– H4e—there were no indirect effects of the examined predictors on actual occupational changes via change intentions (see Table 5). Also, as reported in Table 6, none of the examined predictors showed a significant indirect effect on change intentions via P-J fit, which contradicts H5a–H5d.

Discussion

This longitudinal study aimed to examine predictors of two types of premature contract terminations that represent non-linear career paths: (1) changes of occupations and (2) changes of training companies. Hereby we wanted to refrain from the negative picture often drawn for premature contract terminations and to examine how non-linear career pathways for trainees in VET occur. The results show that actual occupational changes and actual company changes of trainees are affected by the same work-context predictors and pre-entry predictors, in detail trainees’ self-perceived work performance during VET and their effort at the end of compulsory education. Both effects are in line with expectations. The importance of work performance both supports and adds to prior evidence (for newcomers: Kammeyer-Mueller & Wanberg, 2003; for VET: Böhn & Deutscher, 2022; Bosset et al., 2022), since some studies from the VET context suggested performance in vocational schools to be of higher importance than performance in the workplace (e.g., Bosset et al., 2022). Based on the results of Krötz and Deutscher (2022) who showed that training performance is only linked to occupational change intentions but not intentions to change companies, differences between the effects occurring in the two models examined in this study could have been expected. Instead, our results show that self-perceived work performance is equally important for actual occupational and company changes.

The negative effect of adolescents’ pre-entry effort on actual changes is also consistent with expectations. Bosset et al. (2022) found that trainees with premature contract terminations exhibited less effort in vocational school than did trainees who persisted in the training program. Although we did not examine the context of vocational schools, our results underline the importance of individuals’ effort and reveal the long-term effects of effort, since premature contract terminations are directly affected by effort before even starting the training program. This implies that trainees’ motivation is a crucial factor in the decision to terminate the training contract prematurely. Surprisingly, the postulated indirect effects of pre-entry effort on actual changes are not supported by our models, although effort positively affects trainees’ perceptions of the companies’ socialization tactics and of their own work performance (see also Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). In addition, against expectations, pre-entry effort does not significantly predict trainees’ perceived P-J fit. Hence, the role of trainees’ effort in achieving high fit perceptions via proactive behavior that supports socialization processes does not seem as significant as expected.

Besides self-perceived work performance and effort, none of the other predictors examined affect actual changes. Although evidence from newcomer research indicates no direct but indirect effects of organizational socialization tactics on actual changes (Bauer et al., 2007), we expected welcoming socialization tactics to be especially important in the VET context because of the unique structure of VET programs and the young starting age of trainees. Since neither direct nor indirect effects on actual changes are significant in our model, different mechanisms in the VET context compared to newcomers in later stages of the work life do not seem to exist.

Most surprising, though, is the finding contradicting our hypotheses that perceived P-J fit during VET does not significantly predict either type of the actual change examined. This is unexpected, as theory suggests that individuals are more likely to stay in training situations that they perceived to be a good fit for them (e.g., Swanson & Fouad, 1999). For actual changes, however, evidence is scarce. Bosset et al. (2022) showed that trainees who stayed in a VET program and those who terminated their training contract differed significantly regarding fit perceptions. Moreover, premature contract terminations have been linked to whether a trainee is attending a program in their desired occupation (Beicht & Ulrich, 2008; Beicht & Walden, 2013; Michaelis & Richter, 2022). The insignificant effects in our model on occupational change might be explained by the dynamic nature of the fit construct. Since both the training situation and the trainee change over the course of the VET program, there might not be a stable direct relationship between fit and change decisions. When it comes to company changes, changes can be expected to be based more on company decisions than on decisions by the individual trainees. Hence, fit perceptions might not be relevant to actual company changes. Another explanation might lie in the operationalization of fit. Michaelis and Findeisen (2022) showed that objectively evaluated fit indicators did not affect actual premature contract terminations. Consequently, the importance of fit for actual changes in VET programs is not yet clearly determined and different effects might also be due to differences in the operationalization of fit (measurement of fit: perception vs. actual objective fit; aspects of fit: occupation, training program, work environment, interests, skills, etc.). Further research is necessary to examine the relationship between fit and premature contract termination in greater detail, especially regarding the distinction of different operationalizations of fit.

Another interesting finding is that the link between trainees’ change intentions and actual changes expected based on prior studies (e.g., Fieger, 2015; Samuel & Burger, 2019) is only significant for occupational changes and not for company changes. This implies that trainees’ decision-making processes differ between different types of premature contract terminations. Our results indicate that trainees’ own contribution to the termination decision is higher for the decision to change occupations than for the decision to change companies. This might be explained by the fact that actual company changes are less often initiated by the trainees themselves and can also occur as a reaction to termination by the training company. Consequently, this result calls for a more differentiated assessment of different types of changes or dropouts and different types of intentions, as recently implemented by Krötz and Deutscher (2022). Moreover, future studies should be more cautious in assuming that intentions are a valid predictor of dropout decisions since our results indicate that this assumption does not hold for all types of premature contract terminations.

While for actual changes, all but one path are significant in both models examined or not significant in either model, trainees’ intentions to change occupations and their intentions to change companies are revealed to be predicted by different factors. First, perceived P-J fit only significantly affects intentions to change occupations, but not intentions to change companies. This is generally in line with prior evidence from VET that shows that attending a training program in the desired occupation context significantly affected intentions to change occupations and none of the other types of change intentions (Krötz & Deutscher, 2022). Since fit was operationalized rather broadly in our study and assessed with regard to the trainees’ “current training situation”, our results further support the assumption that the decision to change occupations is to a greater extent driven by the trainees themselves compared to the decision to change companies.

Moreover, welcoming socialization tactics by the training company significantly negatively affect trainees’ intentions to change companies and only indirectly affect their intentions to change occupations. This is consistent with the finding that indicators of training quality only affect trainees’ intentions to change companies, but not the other types of intentions (Krötz & Deutscher, 2022). It is very plausible that considerations to change the training company depend on company factors. In contrast, trainees’ decisions to change occupations seem to be less dependent on companies’ socialization tactics and are rather driven by fit perceptions.

The pre-entry effort of trainees, is found to have an indirect effect on intentions to change occupations. However, the direct effect is insignificant for trainees’ intentions to change occupations and significantly positive for their intentions to change companies. The positive effect is against expectations. However, since there is no significant bivariate correlation between effort and intentions to change companies (r = 0.08, n.s.; see Table 2), we refrain from further interpreting the positive effect in the SEM (Fig. 3). The indirect effect is consistent with expectations and supports the assumption that effort fosters trainees’ perceptions of socialization tactics and, therefore, facilitates trainees’ work adjustment (Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000).

Furthermore, in both models, trainees’ intentions are not significantly directly affected by self-perceived work performance, although this factor significantly predicts both types of actual changes. However, we find an indirect effect on intentions to change occupations. This implies that for changes of occupations, perceived work performance affects both intentions and actual changes. The insignificant effect of company changes might be explained by different perceptions of trainees’ performance between the trainees themselves and the supervisor. Company changes might then be initiated by the company. Based on the positive relationship between welcoming socialization tactics and self-perceived performance, negative perceptions of one’s performance might also be due to conflicts in the workplace or high performance requirements by the company. These might lead to terminations initiated by the company, while the trainees might perceive their performance more positively and continue their VET program in a different company.

Finally, anticipated P-J fit is shown to be an indirect predictor of intentions to change occupations but not of intentions to change companies. Anticipated fit is regarded as an indicator of adolescents’ occupational choice process and is expected to facilitate trainees’ integration into the VET program (Nägele & Neuenschwander, 2014). Anticipated fit has been shown to be an indirect predictor of a general intention to terminate the training contract (Findeisen et al., 2022). Our results indicate that the effect depends on the type of change intentions and underline the importance of a distinct analysis of these different types.

This study is subject to several limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results. Although this study provides insights regarding predictors of two different types of premature contract terminations (occupational changes and company changes), we have to acknowledge that both groups are still heterogeneous within themselves. Within the group of trainees with occupational changes, due to sample size restrictions, we were not able to further distinguish between upgrading and downgrading within the same occupational field or a change of occupational fields (see Schmid & Stalder, 2012). It is plausible that there are different predictors of occupational changes depending on whether a trainee starts a new training program in the same or in a different occupational field and whether the new occupation in the same field has higher or lower requirements. For changes of companies, the group of trainees selected for our study possessed all types of events, in which a new training contract was issued by a different company. Reasons for a company change in this sense can be quite broad and include, for instance, not only conflicts with the supervisor but also insolvency of a company or simply a change of the company’s name. Consequently, a more detailed distinction between the two types of premature contract terminations examined in this study could be explored in further research.

In terms of methodological limitations, it should be noted that the time duration between the assessment of change intentions and actual changes within the study sample varied between 1 and 3 years, depending on when the premature contract termination occurred. Moreover, intentions were assessed based on single-item instruments. Hence, limitations with regard to the validity of trainees’ intentions need to be considered. Furthermore, the study is set in the context of dual VET programs in Switzerland. Whether these results are transferable to other national contexts or other types of VET programs (e.g., school-based VET programs) should be examined in future studies.

Moreover, our model focused foremost on predictors of trainees, except for welcoming socialization tactics. This has to do with the longitudinal design in which we followed trainees over the course of the training and were interested in changes in individuals’ perceptions. We did not control for further aspects of training quality or characteristics of the trainers (e.g., competence), although these aspects can be expected to affect premature contract terminations (see Krötz & Deutscher, 2022; Negrini et al., 2016; Stalder, 2012). We were also unable to distinguish between different occupations. Different effects for different training occupations are very plausible; however, the sample sizes in our dataset, unfortunately, did not allow for a further distinction. Therefore, all hypotheses were tested across various occupations. Finally, while focusing on workplace-related aspects, we neglected the context of vocational schools, which also play an important role in VET programs. Hence, aspects of cooperation between vocational schools and workplaces (Bouw et al., 2021a, b) that are important for trainees’ competence development could not be considered as well.

The results have implications for both vocational choice processes and the VET context. The significant effect of pre-entry effort points toward the stability of effort over the transition into VET, in which low effort predicts actual premature contract terminations. This underlines the importance of convincing adolescents about the high importance of vocational education for future career success with the aim of fostering adolescents’ motivation and effort both during vocational choice processes and during the VET program. Here, the relationship with parents and teachers is vital (see Self-Determination Theory; Deci & Ryan, 1993). In addition to effort, trainees’ performance was shown to be crucial for premature contract terminations. This again has implications for vocational choice processes, in which adolescents should choose an occupation that matches their skills, and thus, an occupation in which they are able to meet the performance requirements both in the vocational school and at the workplace. However, since the anticipated P-J fit only affected occupational change intentions, according to our model, the choice of an unsuitable occupation seems to play a smaller (indirect) role in explaining premature contract terminations than originally expected.

In the VET context, implications include the importance of companies’ integration effort at the beginning of the VET program, since welcoming socialization tactics affect change intentions. Also, organizational socialization processes can help trainees to perform their work tasks successfully (Bauer & Erdogan, 2011). Hence, it seems worthwhile, from a company’s perspective, to invest in successfully starting trainees off in their programs. In general, the reasons for premature contract terminations are not only related to individuals but also to companies that play a major role in preventing terminations. For instance, both individuals and training companies are important in achieving a good fit (Swanson & Fouad, 1999). Also, training companies should support trainees who experience performance deficits in order to prevent premature contract terminations (see also Masdonati & Lamamra, 2012). Moreover, the insignificant effect of the intentions to change companies on actual company changes indicates that company changes are initiated by the training company. Nevertheless, these types of premature contract terminations are not necessarily negative, especially when they terminate unfortunate training situations and lead to a new chance of a successful training situation for both trainees and training companies. Generally, non-linear trajectories should not only be viewed negatively, since they do not necessarily have negative effects on individuals’ career successes. Adolescents should be made aware of possible ways to adjust their individual trajectories, for example in case of lack of fit, both during the career choice process and during VET. This could mean expanding career counseling during the transition from school to work and during VET (see Masdonati & Lamamra, 2012; Rübner, 2012). In doing so, the positive aspects of premature contract terminations should be highlighted in oder to counteract the negative image of dropout.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data is available via FORSbase: https://forsbase.unil.ch/project/study-public-list/?csrfmiddlewaretoken=qJxueAdA2SAI3RJ3b2Ph54GCQlwF3FvWQBqgf61pMtKlvCVPZVNBCWNv9URCvsK6&q=wisel&ds_topic_id=-1&language_id=-1&discipline_id=-1&method_instrument_id=-1&financing_id=-1&study_type_id=-1&from_date=&to_date=&search=Suchen&show_hide=0.

References

Allen, M. S., Iliescu, D., & Greiff, S. (2022). Single item measures in Psychological Science. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 38(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000699

Bauer, T. N., & Erdogan, B. (2011). Organizational socialization: The effective onboarding of new employees. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Volume 3: Maintaining, expanding, and contracting the organization (pp. 51–64). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12171-002

Bauer, T. N., Bodner, T., Erdogan, B., Truxillo, D. M., & Tucker, J. S. (2007). Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 707–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.707

Beicht, U., & Ulrich, J. G. (2008). Ausbildungsverlauf und Übergang in Beschäftigung. Teilnehmer/-innen an betrieblicher und schulischer Berufsausbildung im Vergleich [Training progression and transition to employment. Participants in in-company and school-based vocational training in comparison]. Berufsbildung in Wissenschaft und Praxis, 3, 19–23.

Beicht, U., & Walden, G. (2013). Duale Berufsausbildung ohne Abschluss - Ursachen und weiterer bildungsbiografischer Verlauf: Analyse auf Basis der BIBB-Übergangsstudie 2011 [Dual vocational training without a qualification - Causes and further educational biographical progression: Analysis based on the BIBB Transition Study 2011]. BIBB Report, 7(21), 1–15.

Bergkvist, L. (2015). Appropriate use of single-item measures is here to stay. Marketing Letters, 26(3), 245–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-014-9325-y

Bessey, D., & Backes-Gellner, U. (2015). Staying within or leaving the apprenticeship system? Revisions of educational choices in apprenticeship training. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik, 235(6), 539–552.

Böhn, S., & Deutscher, V. (2022). Dropout from initial vocational training – A meta-synthesis of reasons from the apprentice’s point of view. Educational Research Review, 35, 100414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100414

Bosset, I., Hofmann, C., Duc, B., Lamamra, N., & Krauss, A. (2022). Premature interruption of training in Swiss 2-year apprenticeship through the lens of fit. Swiss Journal of Educational Research, 44(2), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.24452/sjer.44.2.9

Bouw, E., Zitter, I., & de Bruijn, E. (2021a). Exploring co-construction of learning environments at the boundary of school and work through the lens of vocational practice. Vocations and Learning, 14(3), 559–588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-021-09276-2

Bouw, E., Zitter, I., & de Bruijn, E. (2021b). Multilevel design considerations for vocational curricula at the boundary of school and work. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 53(6), 765–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2021.1899290

Buchmann, M. (1989). The script of life in modern society: Entry into adulthood in a changing world. Univ. of Chicago Press.

Cable, D. M., & Parsons, C. K. (2001). Socialization tactics and person-organization fit. Personnel Psychology, 54(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00083.x

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Cho, Y. J., & Lewis, G. B. (2012). Turnover intention and turnover behavior. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 32(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X11408701

Cohen, G., Blake, R. S., & Goodman, D. (2016). Does turnover intention matter? Evaluating the usefulness of turnover intention rate as a predictor of actual turnover rate. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 36(3), 240–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X15581850

Dalton, D. R., Johnson, J. L., & Daily, C. M. (1999). On the use of “Intent to…” variables in organizational research: An empirical and cautionary assessment. Human Relations, 52(10), 1337–1350. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679905201006

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). Die Selbstbestimmungstheorie der Motivation und ihre Bedeutung für die Pädagogik [The self-determination theory of motivation and its significance for pedagogy]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 39(2), 223–238.

Deuer, E., & Wild, S. (2018). Validierung eines Instruments zur Erfassung der Studienabbruchneigung bei dual Studierenden [Validation of an instrument to measure dropout intention among dual students]. Forschungsberichte zur Hochschulforschung an der DHBW, 4/2018.

Diamantopoulos, A., Sarstedt, M., Fuchs, C., Wilczynski, P., & Kaiser, S. (2012). Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: A predictive validity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0300-3

Englund, M. M., Egeland, B., & Collins, W. A. (2008). Exceptions to high school dropout predictions in a low-income sample: Do adults make a difference? Journal of Social Issue, 64(1), 77–94.

Federal Statistical Office. (2021). Lehrvertragsauflösung, Wiedereinstieg, Zertifikationsstatus: Resultate zur dualen beruflichen Grundbildung (EBA und EFZ). FSO.

Fieger, P. (2015). Determinants of course completions in vocational education and training: Evidence from Australia. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 7(1), 455. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-015-0025-5

Findeisen, S., Jüttler, A., Neuenschwander, M. P., & Schumann, S. (2022). Transition from school to work – Explaining persistence intention in Vocational Education and Training in Switzerland. Vocations and Learning, 15(1), 129–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-021-09282-4

Frey, A., Ertelt, B.-J., & Balzer, L. (2012). Erfassung und Prävention von Ausbildungsabbrüchen in der beruflichen Grundbildung in Europa: Aktueller Stand und Perspektiven [Recognition and prevention of dropout in basic vocational training in Europe: Current situation and prospects]. In C. Baumeler, B.-J. Ertelt, & A. Frey (Eds.), Bildung, Arbeit, Beruf und Beratung: Bd. 1. Diagnostik und Prävention von Ausbildungsabbrüchen in der Berufsbildung (pp. 11–60). Empirische Pädagogik.

Hirschi, A. (2011). Career-choice readiness in adolescence: Developmental trajectories and individual differences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 340–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.005

Holtmann, A. C., & Solga, H. (2023). Dropping or stopping out of apprenticeships: The role of performance- and integration-related risk factors. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 26(2), 469–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-023-01151-1

Janosz, M., Archambault, I., Morizot, J., & Pagani, L. S. (2008). School engagement trajectories and their differential predictive relations to dropout. Journal of Social Issues, 64(1), 21–40.

Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Wanberg, C. R. (2003). Unwrapping the organizational entry process: Disentangling multiple antecedents and their pathways to adjustment. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 779–794. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.779

Kemmler, A. (2012). Analyse von Ausbildungsabbrüchen im Kontext der Leistungsmotivation [Analysis of dropout from vocational training in the context of achievement motivation]. In C. Baumeler, B.-J. Ertelt, & A. Frey (Eds.), Bildung, Arbeit, Beruf und Beratung: Bd. 1. Diagnostik und Prävention von Ausbildungsabbrüchen in der Berufsbildung (pp. 162–185). Empirische Pädagogik.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

Krötz, M., & Deutscher, V. (2021). Differences in perception matter – How differences in the perception of training quality of trainees and trainers affect drop-out in VET. Vocations and Learning, 14(3), 369–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-021-09263-7

Krötz, M., & Deutscher, V. (2022). Drop-out in dual VET: Why we should consider the drop-out direction when analysing drop-out. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 14(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-021-00127-x

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2008). Social Cognitive Career Theory and subjective well-being in the context of work. Journal of Career Assessment, 16(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072707305769

Lent, R. W., Miller, M. J., Smith, P. E., Watford, B. A., Lim, R. H., & Hui, K. (2016). Social cognitive predictors of academic persistence and performance in engineering: Applicability across gender and race/ethnicity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94, 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.02.012

Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

Masdonati, J., & Lamamra, N. (2012). Prävention und Begleitung vorzeitiger Abbrüche in der dualen Berufsbildung [Dropout prevention and support measures for dropouts in dual vocational trianing]. In C. Baumeler, B.-J. Ertelt, & A. Frey (Eds.), Bildung, Arbeit, Beruf und Beratung: Bd. 1. Diagnostik und Prävention von Ausbildungsabbrüchen in der Berufsbildung (pp. 107–121). Empirische Pädagogik.

Maué, E., Findeisen, S., & Schumann, S. (2023). Development, predictors, and effects of trainees’ organizational identification during their first year of vocational education and training. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1148251. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1148251

Mayer, K.U. (2001). Lebensverlauf [Life course]. In B. Schäfers & W. Zapf (Eds.), Handwörterbuch zur Gesellschaft Deutschlands (2nd ed., pp. 446–460). Leske+Budrich.