Abstract

Background/purpose

The aims of this study are: (1) to examine the mediating effect of teacher self-efficacy on the relationship between trust in colleagues and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB); and (2) to evaluate the moderating effect of collective efficacy on the relationships between teachers’ self-efficacy and OCB, as well as between trust in colleagues and OCB.

Design/methodology/approach

The cross-sectional data were based on 408 sets of usable questionnaires collected from teachers who worked in government schools in Malaysia. The partial least square structural equation modeling technique was used to test the model and hypotheses.

Findings

The results indicate that trust in colleagues is positively related to organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and teacher self-efficacy. Additionally, teacher self-efficacy and OCB are also positively related. Furthermore, the relationship between trust in colleagues and OCB is partially mediated by teacher self-efficacy. Moreover, collective efficacy significantly moderates the path between teacher self-efficacy and OCB but not between trust in colleagues and OCB.

Originality/value

Despite earlier studies examining the relationship between trust, teacher self-efficacy, and OCB, little is known about the mediating mechanism of teacher self-efficacy and the moderating effect of collective efficacy. Thus, this present study makes significant contributions in both theoretical and practical aspects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The teaching profession is becoming increasingly challenging due to continuous education reforms. These transformations require teachers to be highly adaptable in coping with new schemes and rules and dealing with heavier workloads. As a result, teachers must commit to working beyond their formally contracted job duties and role obligations to excel and succeed in the education field [1,2,3].

Given these demands, it is crucial to understand the factors that shape teachers’ organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), a type of behavior that goes beyond formal job requirements to benefit the organization [4, 5]. According to Luthans and Youssef [6], OCB is a prototypical form of Positive Organizational Behavior (POB). Individuals with high OCB are more inclined to assist others, build relationships, and thrive at work. This behavior contributes significantly to the performance and effectiveness of schools, as evidenced by numerous empirical studies [7,8,9,10]. OCB is recognized as one of the most extensively studied outcomes in organizational behavior and industrial psychology, particularly within the education sector [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Previous research has highlighted the critical role of OCB in promoting a conducive working atmosphere and achieving organizational goals [7,8,9,10]. Studies have also revealed that OCB contributes significantly to the welfare of individuals, groups, and organizations [17]. By fostering a positive and collaborative work environment, OCB plays a crucial role in the overall success and effectiveness of educational institutions.

OCB is distinct within the broader employee behavior literature because it focuses on discretionary behaviors beyond formal job requirements, ultimately enhancing organizational functioning. DiPaola and his colleagues argued that OCB can be defined differently in service organizations such as universities, hospitals, and schools, which typically employ professionals to work within their organizations [18]. This is because OCB in education is distinct from OCB in other service organizations due to the nature of professional roles. Teachers often have roles that extend beyond traditional job descriptions. Their professional responsibilities include mentoring, community engagement, and contributing to the holistic development of students, which requires a broader and more flexible definition of OCB. Schools aim primarily to improve student achievement. Helpful behaviors by teachers benefit both students and colleagues, supporting the school’s mission of helping people. Collaboration among teachers in teaching and their support for students learning contribute to the achievement of the school’s overall goals [19, 20]. Therefore, teachers’ professional goals are closely aligned with the school’s organizational goals. This shows that teaching differs greatly from private organizations and other professions or types of service employee behavior [21].

To date, the existing studies have empirically affirmed that organizational justice [11], teacher self-efficacy [22], perceived organizational support [23], human resource management practices [8], and leader-member exchange [24] are significantly related to OCB among teachers. Notwithstanding these abundant research outcomes, empirical studies that examined trust and efficacy constructs in connection with OCB remain limited [22, 25]. Both trust and efficacy constructs (i.e., teacher self-efficacy and collective efficacy) are paramount in enhancing interpersonal relationships between the leader and employees in general [26]. Zheng et al. [27] explicitly indicated that a trusting relationship among teachers is one of the best ways to improve the effectiveness of teachers’ collaboration. Moreover, trust facilitates interaction and understanding among teachers. Thus, it is undoubtedly essential in strengthening and promoting a harmonious relationship in the school. In turn, teachers will be more passionate about practicing OCB, such as assisting a colleague to accomplish challenging tasks and accommodating the colleague’s work schedule. On the other hand, self-efficacy is recognized as an important personal resource that can promote an individual’s performance both at work and in the educational context [28]. Teachers with high self-efficacy are confident in their ability to manage classrooms, address challenges, and achieve goals. This confidence motivates them to go beyond their primary responsibilities, positively contributing to the school environment through OCB [29].

Based on the above argument, we propose two research objectives for this study. The first focal point of this paper is to examine the mediating effect of teacher self-efficacy on the relationship between trust in colleagues and OCB. We contended that trust would significantly encourage teachers to practice OCB, provided that they are competent enough to assist others in the workplace [9]. Choong et al. [22] argued that teachers with mutual understanding and high acceptance would further encourage them to interact and communicate more openly, which stimulate an authentic form of collaboration in the school. Eventually, trust among colleagues improved teachers’ self-efficacy, further fostering their interpersonal altruism [30, 31]. Nonetheless, teachers’ trust in their colleagues would not necessarily induce their strong desire to offer assistance or lend their helping hands to others unless they possess sufficient skill, confidence, and capabilities.

Huang et al. [32] reveal that as long as trust among colleagues is formed, continuous collaboration and professional learning communities will be developed, which would enhance teachers’ self-efficacy. Eventually, teachers will have confidence in their ability to execute the desired behavior. This could be further explained in the agentic perspective of social cognitive theory (SCT) [33] argued that “human behaviors are characterized by intention (i.e., actions are originated for specific purposes) and forethought (i.e., behaviors are regulated in accord with outcome expectations), in which both are driven by self-reflectiveness about one’s capability” [34].

The second focal point of this study is to test the moderating effect of collective efficacy on the relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy and OCB, as well as the relationship between trust in colleagues and OCB. Earlier findings indicated that collective efficacy is an effective mediator [1, 35,36,37], precursor [35, 38], and even an outcome [1, 35, 39] of OCB, however, the existing literature rarely examined the moderating effect of collective efficacy on OCB. As such, it becomes one of the areas that remain underexplored in organizational behavior literature, in which this research intends to fill the gap by treating collective efficacy as a moderator between teacher self-efficacy and OCB as well as trust in colleagues and OCB.

We argued that the effect of the proposed direct relationship is stronger when teachers perceived collective efficacy is high. Teachers who share the same belief in the organization tend to join together and pool their resources to achieve their mutual objective or to solve their common problem [40]. Lev and Koslowsky [40] asserted that teachers tend to dwell on a school’s past achievement and success. A high trust workplace allows teachers to work together in a comfortable environment and assist each other.

This study is expected to contribute to the extant organizational behavior literature by integrating trust in colleagues, teacher self-efficacy and collective efficacy as factors of OCB. Accordingly, two research questions are derived from the research objectives: (1) Does teacher self-efficacy mediate the relationship between trust in colleagues and OCB? (2) Does collective efficacy moderate the proposed direct paths? This paper unfolds as follows. A detailed literature review with underpinning theories and hypotheses development is presented in the following section. The subsequent part includes the research method, data analysis, and presentation of results. The final section covers the discussion of results, implications, and conclusion.

Literature review

Theoretical background

Two theories, Social Exchange Theory (SET) and SCT are used as an underlying basis to understand the social interaction between two parties in a school context. SET is conceptualized as a type of exchange relationship that goes beyond the employment contract in which people engage in an action that generates reciprocate exchange obligations between two or more parties [41, 42]. The relationship with an organization is viewed by an individual as being an acceptable commodity for exchange, whereby the quality of the relationship is built upon the principle of reciprocity [43]. It simply means that an individual tends to behave in a way that is perceived to be appropriately recompensed for how an organization has treated the individual [11]. Thus, we argued that teachers would do more and move beyond the call of duty by helping their colleagues to accomplish their work if their colleagues trusted them. Colleague support would prompt an obligation to repay favor from one another by devoting extra resources and effort to the assigned tasks [44]. We also contended that a supportive gesture, as portrayed by teachers in every day’s schoolwork, can trigger a personal emotional state to feel more attached to the school in which they are serving. Thus, it could further enhance teachers’ confidence in performing their daily tasks.

SCT is defined as an individual’s belief in his or her capability to organize and implement a plan of action necessary for goal attainment [45]. The SCT states that the efficacy belief is anchored in the agency assumption, in which there is a high possibility for individuals to perform certain activities when they believe in their capability to complete the duties or tasks [46,47,48]. As such, teachers who possess a high level of efficacy will have great confidence and a strong belief that they are able to carry out specific tasks successfully and provide helping hands to colleagues [1]. Apart from this, we also asserted that collective efficacy could act as a moderator on the relationship between trust in colleagues and OCB as well as teacher’s self-efficacy and OCB. Schechter and Tshcannen-Moran [49] denoted that teachers with a high sense of individual self-efficacy might have a different level of performance in a high collective efficacy environment. Individual teachers with a high efficacy level may not necessarily perform well or be willing to provide support to their colleagues if they perceive a low sense of conjoint capability to perform and achieve a common objective. Goddard and Goddard [48] added that individual self-efficacy and collective efficacy are different constructs, but both can be influenced by one another in reciprocal ways. Similarly, teachers who trusted their colleagues would offer their assistance to their colleagues as they believed that their team members could perform well in the given tasks.

Trust in colleagues and organizational citizenship behavior

Trust is depicted as “a person is willing to be vulnerable to another based on the confidence that the other is benevolent, honest, open, reliable and competent” [50]. Hoy and his colleagues contended that trust is a multifaceted construct comprised of benevolence, reliability, competency, honesty, and openness. This multifaceted construct can be related to several referent groups such as teachers, students, parents, administrators, and organizations. However, trust in colleagues is the only focus of this research as teachers spend most of the time with their colleagues in order for them to accomplish their daily tasks. Zheng et al. [34] explained that employee experience of felt trust might influence their in-role and extra-role performance. Teachers who trust their colleagues tend to believe that such citizenship behavior could be reciprocated if they openly share information and be true to others [22, 51]. According to SET, individuals engage in behaviors that they believe will be reciprocated. When teachers trust their colleagues, they are more willing to go beyond their job requirements, knowing that their efforts will be acknowledged and reciprocated (52,53). This mutual support fosters a positive work environment where OCB thrives. Conversely, teachers may not offer their kind help to their colleagues who are always unreliable, not good-natured, and not big-hearted. Edwards-Groves et al. [54] clearly expressed that trust is not only the foundation of school effectiveness and student achievement, but it also leads to open communication and an authentic form of collaboration among teachers.

In addition, the reciprocity inherent in SET explains why trust leads to increased OCB. Teachers who trust their colleagues are more likely to exhibit helping behaviors because they anticipate mutual support in return, reinforcing a culture of collaboration and mutual aid. This aligns with the findings of Choong et al. [52, 53], who demonstrated that trust within teams not only enhances collaboration but also motivates individuals to go beyond the basic requirements of their roles to contribute to the success of their colleagues and the organization as a whole. Khan et al. [55] further support this notion by highlighting how the quality of supervisor-subordinate Guanxi (i.e., interpersonal relationships) significantly influences employees’ work behaviors. Positive Guanxi fosters trust and mutual understanding, which, in turn, leads to enhanced work behaviors, including increased cooperation and OCB. Additionally, Chughtai and Khan [56] emphasize that trust and knowledge-oriented leadership contribute to employees’ innovative performance by creating an environment where they feel supported and motivated to take the initiative. These findings collectively signify the pivotal role of trust in not only promoting OCB but also in stimulating innovation and enhancing overall work behavior through strong interpersonal relationships. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Trust in colleagues is positively related to organizational citizenship behavior.

Teacher’s self-efficacy as mediator

The existence of trustworthiness between colleagues will provide a feeling of safety with positive thinking. It fosters relationships among colleagues by openly sharing information and being truthful with others. This further encourages them to learn from their colleagues, which in turn promotes a greater sense of efficacy [51]. Teacher’s self-efficacy is defined as “the teacher’s belief in his or her capability to organize and execute courses of action required to accomplish a specific teaching task in a particular context” [57]. Yin et al. [58] indicated that integrity and authenticity among colleagues would enable teachers to appraise others truthfully. Trust can serve as a source of self-efficacy where it strengthens an individual’s belief that he or she is capable of performing a specific task [34, 59]. It can be done through felt-reliance and felt-disclosure. People who are equipped with relevant work-related skills and knowledge possess a good working capability that others can rely upon. Likewise, a trusting working environment in school facilitates the sharing of information and skills among colleagues, encouraging others to share their resources reciprocally, which is beneficial for teachers to accomplish their tasks and work goals.

SCT explains that trusted colleagues often provide encouragement and constructive feedback, which are crucial components of social persuasion [60]. Positive reinforcement from trusted peers strengthens teachers’ belief in their ability to perform teaching tasks effectively [61]. Studies by Ma et al. [62] highlighted that verbal encouragement, especially when provided by trusted colleagues, significantly boosts teachers’ self-efficacy, assuring them of their capability to meet their professional demands. This verbal encouragement directly enhances self-efficacy. Thus, trust not only facilitates resource sharing and collaboration but also plays a key role in enhancing teachers’ self-efficacy through social persuasion and feedback mechanisms. The trusting relationships between colleagues allow for continuous professional development, helping teachers build the confidence they need to succeed. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2

Trust in colleagues is positively related to teacher’s self-efficacy.

Dybowski et al. [63] contended that teachers with a greater sense of self-efficacy are more desirous and ambitious to set challenging goals for themselves. Teachers with high self-efficacy are self-assured that they can influence students’ learning outcomes and academic achievement [64, 65]. Besides, they tend to have greater persistence in the face of adversity and willingness to work beyond the call of duty [1, 22]. From the perspective of SCT, “efficacy beliefs determine how environmental opportunities and impediments are viewed” [66]. Thus, Skaalvik and Skaalvik [35] argued that efficacy belief could influence individual goals, motivation, behaviors, and even extra-role behaviors. If people regard themselves as capable of performing the assigned tasks, they are more confident and obliging. Paramasivam [67] elucidated that teachers are solely driven by internal motives instead of external motives such as rewards and recognition. Teachers’ key driving factors for performing OCB are primarily based on their internal belief system, such as self-confidence and a strong belief that they are able to make a difference.

SCT highlights that teachers with high self-efficacy often model positive behaviors for their peers [68]. When they engage in OCB, such as volunteering for extra duties or supporting colleagues, they set an example for others to follow [69]. Observing these behaviors can inspire other teachers to adopt similar actions, creating a culture of OCB within the school. SCT further suggests that as teachers with high self-efficacy engage in these behaviors, they often receive positive reinforcement from their peers and administrators, further strengthening their belief in their capabilities. This ongoing feedback loop reinforces the connection between self-efficacy and OCB, creating a sustainable culture of mutual support and collaboration [52, 53]. Thereby, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 3

Teacher’s self-efficacy is positively related to organizational citizenship behavior.

As noted earlier, teachers are keen to learn from each other in a trusting atmosphere and develop their sense of efficacy. Similarly, teachers with high self-efficacy often show citizenship behavior. However, we contend that teachers who trust their colleagues may not necessarily demonstrate extra-role behavior if they do not have adequate confidence and skill to help others [22]. On the contrary, teachers with high self-efficacy are more eager to help those authentic colleagues. In short, trust can foster and sustain a quality relationship between colleagues by encouraging them to have healthy communication that further stimulates cooperation and knowledge sharing. This, in turn, will lead them to learn from each other. Subsequently, this enhances their confidence and capability to extend their helping hands to others who face difficulties in their job. Otherwise, an untrustworthy relationship will discourage teachers, more self-serving and not willing to help others. Zheng et al. [34] indicated that teachers’ confidence and capability are the pre-conditions for effective task accomplishment. Moreover, Huang et al. [32] as well as Yin et al. [56] connoted that trust in colleagues could be a form of support that triggers more collaboration and creates a mutual learning community in the workplace. This could serve as a platform for teachers to learn from each other and enhance individual self-efficacy, which eventually encourages them to help others and share their valuable knowledge. As indicated by SET, teachers who trust their colleagues and feel efficacious are more likely to engage in OCB, which in turn reinforces trust and further enhances self-efficacy (53). As they help others and share their knowledge, they reinforce a positive cycle where trust is continually built, and self-efficacy is further enhanced [70]. This reciprocal dynamic creates a supportive and collaborative work environment where OCB thrives, and teachers are more willing to contribute beyond their formal responsibilities. Therefore, trust and self-efficacy work together to foster a culture of collaboration and mutual aid among teachers. Trust facilitates the exchange of knowledge and the development of self-efficacy, while self-efficacy empowers teachers to engage in OCB, which in turn reinforces trust. Thus, we propose the following mediating hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4

Teacher’s self-efficacy mediates the relationship between trust in colleagues and organizational citizenship behavior.

Collective efficacy and moderator

Collective efficacy is defined as “an individual teacher’s beliefs that the school as a whole can implement and organize courses of actions affecting students and their levels of attainments” [71]. The strength of the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and OCB is stronger in a higher collective efficacy environment, while the relationship is weaker when there is low collective efficacy in a school milieu. Likewise, we also postulated that the strength of the relationship between trust in colleagues and OCB is stronger when collective efficacy among school teachers is high. On the contrary, this relationship will be weaker if the teacher perceives a lower sense of collective efficacy.

SCT posits that individual self-efficacy is influenced by collective efficacy, which is the group’s shared belief in its conjoint capabilities to organize and execute actions required to achieve goals [72]. Teachers with high self-efficacy are more likely to engage in OCB if they are part of a group that believes in its collective power to effect change. Lev and Koslowsky [40] argued that teachers are more willing to assist and support others if they have a common belief and are willing to pool their resources and share useful skills with others. Conversely, if teachers do not have confidence in their teams’ or colleagues’ capabilities in achieving the common objective, they are less likely to help others even though they have the resources such as skills, knowledge, experiences, and time. Goddard et al. [73] explain that an individual’s perceived collective efficacy would strongly influence faculty members’ effort and persistence. Teachers will not work beyond their formal job description if they find that their members do not put effort and lack of persistence in performing their tasks. Therefore, we argue that in an environment of high collective efficacy, there is a stronger sense of trust and mutual benefit among teachers (74).

Schools with a high sense of collective efficacy tend to have a stronger sense of trust and mutual benefit among teachers [36]. SET suggests that this trust fosters social exchanges that promote OCB, as teachers feel more secure in their roles and valued by their colleagues. In such environments, teachers are more likely to go above and beyond their formal roles, knowing that their contributions will be acknowledged and reciprocated by their peers [22]. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5

Collective efficacy moderates the relationship between teacher’s self-efficacy and organizational citizenship behavior, such that the relationship is stronger at high than low level of collective efficacy.

Hypothesis 6

Collective efficacy moderates the relationship between trust in colleague and organizational citizenship behavior, such that the relationship is stronger at high rather than low level of collective efficacy.

Proposed research model

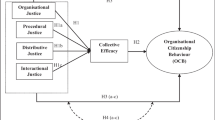

A research model is proposed and shown in Fig. 1. Both SET and SCT are used to support the proposed research model. Overall, the aim of this study is twofold. First, we postulated that teacher self-efficacy significantly mediates the relationship between trust in colleague and OCB. Second, individual level of collective efficacy will significantly moderate the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and OCB as well as between trust in colleagues and OCB.

Research methodology

Procedures and participants

Respondents were full-time teachers from Malaysian government schools. A paper-based questionnaire was used to collect the data on teachers’ perceptions toward trust in colleagues, efficacy, and citizenship behavior in the workplace. The fieldwork took place from September 2019 to October 2019 in 26 government secondary schools in Malaysia. Five well-trained research assistants were recruited to assist in data collection and they were briefed on the nature of the study, structure, and content of the survey and do and don’ts while approaching respondents. A quota sampling technique was used to select respondents, ensuring an equal sample from each school was approached and included in the study. We invited 20 teachers from each school to participate in our survey. Prior to fieldwork, ethical clearance was obtained from the research director of the institution and permission was granted by the Ministry of Education to conduct the survey in schools. A total of 520 teachers were invited to partake in the survey anonymously. Out of 520 teachers, 438 teachers agreed to respond to the survey. However, only 408 sets of questionnaires were usable which yielded a 78.46% response rate. Mellahi and Harris [74] highlighted that the acceptable range of response rates for top-tier journals in the areas of general management is 50%. Therefore, the response rate of 78.46% is good and acceptable. G*power software was used to check the sufficiency of sample size for data analysis [75]. With type-1 error probabilities of 0.05, the sample of 408 is also deemed to be sufficient to produce a statistical power of 80% for a moderate effect size of 0.15 [76].

The sample comprised of 162 (40%) male teachers and 246 (60%) female teachers. Most of teachers were married (n = 271, 66%), and earned a bachelor’s degree (n = 282, 69%). Out of 408 teachers, 152 (37%) teachers were less than 30 years old, 112 (27%) teachers fall within the range of 31 to 40 years old, 102 (25%) teachers aged from 41 to 50 years old and 42 (11%) teachers age more than 50 years old. Regards to teaching experience, 126 (31%) of them with less than 5 years of teaching experience, 76 (19%) teachers with 5 to 10 years, 83 (20%) teachers with 11 to 15 years, 81 (20%) teachers with 16 to 20 years, 11 (3%) teachers with 21 to 25 years and 30 (7%) senior teachers with more than 25 years teaching experience. There were fairly balanced in terms of organizational tenure which 209 (51%) teachers providing their service in their current school for more than 10 years and 199 (49%) teachers serve in their current school for less than 10 years.

Research instruments

The paper-based survey consists of two parts. Part one comprises of 51 items which used to measure trust in colleague, teacher’s self-efficacy, collective efficacy and organizational citizenship behavior. All of these items were adapted from past studies and were measured with a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Part two comprised of 6 items pertaining to respondents’ characteristics such as gender, age, marital status, educational background, teaching experience, and organizational tenure. These items were measured with either an ordinal scale or a nominal scale.

Trust in Colleague. The scale was developed by Hoy and Tschnannen-Moran [77] which consists of eight items. Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement on the statements which reflect their level of trust towards their colleague. Items include “I am open with each other in my school” and “I have faith in the integrity of my colleague in my school”. The inter-item reliability for the 8-item scale was 0.85.

Teacher Self-Efficacy. We measured teacher self-efficacy with a 16-item measurement scale advanced by Gibson and Dembo [78]. Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement on the statements that describe their efficacy in performing teaching tasks. For instance, “When a student gets a better grade than he usually gets, it is common because I found better ways of teaching that student”. The internal consistency of this scale was 0.87.

Collective Efficacy. A twelve-item scale from Goddard [79] was adapted to measure collective efficacy. Respondents were requested to assess the extent to which the listed statements described their perception towards team or school conjoint capability in dealing with school common goals. An example of the item is “Teachers here are confident because they able to motivate their students.” The inter-item reliability for the 12-item scale was 0.91.

Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Organizational citizenship behavior was assessed with a single dimension comprised of 15 items developed by Dipaola and Tschannen-Moran [80]. Respondents were requested to assess the extent to which the listed statements described their willingness to exercise citizenship behavior in the school. Sample items include “I help teachers voluntarily” and “I take the initiative to introduce myself to assist teachers”. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was 0.96.

Several control variables were included in this study, such as gender, age, marital status, teaching experience, and organizational tenure. Marinova et al. [81] indicated that male married employees have higher tendencies to engage in OCB than female married employees or male non-married employees. Furthermore, Caesens and Stinglhamber [82] highlighted that senior employees with longer organizational tenure and more extensive work experience are more willing to help others.

Data analysis

Two software were used to analyze the data: Statistical Package of Social Science (SPSS V25) and Smart PLS version 3. Specifically, the descriptive analysis includes means, standard deviation, inter-correlations, and Harman Single factor test were conducted using SPSS software, whereas construct validity, reliability and structural model analysis were examined through Smart PLS software. The Smart PLS software was used as the main statistical tool to examine the research model as the direct paths, indirect path and moderation path can be tested together by using a structural equation modeling technique. Based on Hair et al. [83], the PLS-SEM approach is superior to regression analysis when assessing mediation.

The data analysis was divided into four parts: descriptive analysis, preliminary analysis, measurement model analysis and structural model analysis, which includes the testing of direct effect, mediating effect, and moderating effect paths analysis.

Descriptive analysis

Table 1 reveals the mean, standard deviation, and inter-correlation scores. Based on the inter-correlation analysis, all the variables are inter-correlated with each other. In contrast, none of the control variables (gender, age, marital status, teaching experience, and organizational tenure) are correlated with the study variables. This shows that the control variables did not significantly influence the outcome variable of this research (i.e., OCB).

Preliminary analysis

Due to the nature of the study, the data was collected through a single source which may raise the concern of common method bias [84]. Therefore, a Harman single factor test was pursued to ensure the data set was free from common method bias. An un-rotated factor analysis was performed using SPSS software. The first factor accounted 23.1 per cent of the variance which was well below the threshold value of 50 per cent [84]. In addition, we tested the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), ensuring that all VIF scores were not more than 3.3, as recommended by Kock [85]. The VIF scores range from 1.004 for collective efficacy to 1.580 for trust in colleague. Therefore, the common method bias is not a serious threat in this study whereby the variations in responses may be caused by the actual predispositions of the respondents. For the normality of the data, both kurtosis and skewness were analyzed. It’s indicated that the data was normally distributed with less than the cut-off value of 2 [86].

Measurement model analysis

For the evaluation of the measurement model, the loadings, average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability were assessed. Table 2 shows the factor loadings score for items, average variance extracted (AVE) score and composite reliability score for each construct. The majority of the items were with factor loadings of 0.70 by Hair et al. [83]. However, several items’ loadings: two items from trust in colleagues and two items from teaching self-efficacy were lower than 0.70 which have been removed from the measurement model. All constructs’ AVE scores were greater than the threshold value of 0.50, ranging from 0.57 for teacher self-efficacy to 0.81 for OCB. At the same time, the composite reliability scores for constructs exceeded the minimum recommended value of 0.70 by Hair et al. [83]. Thus, it can be concluded that the measurement model possesses adequate convergent validity.

The Fornell and Larcker criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) criterion were used to confirm the discriminant validity of the measurement model. Table 3 reveals that none of the correlation values are greater than the scores on the diagonal (i.e. square root of AVE). Table 4 demonstrates that none of the HTMT criterion scores exceeded the conservative standard rule of thumb (HTMT0.85) [87]. As such, all the adopted constructs were distinct, and discriminant validity was well affirmed.

Structural model analysis

Following Hair et al.’s [83] recommendations, a bootstrapping technique with 5000 re-sample were conducted to generate path coefficients score, t-statistics, p-values, confidence intervals and effect sizes. The explanatory power for OCB was 0.80 (R2) and teacher self-efficacy was 0.60 (R2). Table 4; Fig. 2 demonstrate that trust in colleague is positively related to OCB (β = 0.12, t = 1.75, p < 0.05) and teacher self-efficacy (β = 0.77, t = 22.39, p < 0.001). The relationship between teacher self-efficacy and OCB was also shown positively significant (β = 0.38, t = 4.59, p < 0.001). Thus, hypotheses 1 to 3 were supported by the data. For mediation analysis, the relationship between trust in colleague and OCB is significantly mediated by teacher self-efficacy (β = 0.29, t = 4.72, p < 0.001), thereby supporting hypothesis 4. Since the direct path of trust in colleague and OCB is also significant, therefore, the mediation path is considered partial mediation [88]. The moderation analysis showed that collective efficacy significantly moderates the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and OCB. Figure 3 depicts that teacher self-efficacy is positively related to OCB when collective efficacy is high. Nevertheless, when collective efficacy is low, teacher self-efficacy leads to a decline in OCB. Thus, hypothesis 6 is supported. On the other hand, hypothesis 7 is not supported, as collective efficacy did not moderate the relationship between trust in colleagues and OCB (Table 5).

Moderation graph for Hypothesis 5

Teacher self-efficacy has the strongest impact on teacher self-efficacy, with an effect size (f2) of 1.47, exceeding 0.35, which indicates a large effect size [89]. The effect size for the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and OCB was at a moderate level (> 0.15). The remaining relationships fall within the small effect size range (> 0.02), except for the relationship between trust in colleague and OCB.

Discussion

Despite earlier studies have examined the relationship between trust, teacher self-efficacy and OCB [22, 35, 51, 53], little is known about the mediating mechanism of teacher self-efficacy and moderating effect of collective efficacy. Our present study reveals that trust in colleagues is positively related to OCB. This finding is consistent with past studies [1, 34]. As contended by Zheng et al. [34] (2019), trust could lead employees to perform both in-role and extra-role behaviors. Teachers tend to share their genuine feelings during their interpersonal interactions in a trustful environment [90]. It’s even encouraged them to openly share their knowledge with colleagues, and subsequently prompts them to repay a favor from one another by performing extra-role behavior [44, 51].

The result of this study further demonstrated that teacher self-efficacy mediates the relationship between trust in colleagues and OCB. Choong et al. [22] posited that trust in colleagues has a positive role in improving teacher self-efficacy. This is affirmed by Bandura [59] and Zheng et al. [34] that trust can serve as a source of self-efficacy by persuading someone to believe that they can perform difficult task successfully. An authentic kind of collaboration would strengthen the teacher’s efficacy by sharing and learning from others. A capable teacher would then be more willing to help others [35]. Ng and Lucianetti [91] further argued that trust creates an environment that enhances individual self-efficacy. Trust is a form of positive emotional signal to self-efficacy that impel innovative behavior. Teachers tend to be supportive and create a mutual learning community by encouraging more collaborations and sharing which further enhance each other efficacy level [56]. A trustful climate not only enhances self-efficacy but also stimulates teachers to actively practice citizenship behavior [35]. As denoted by Choong et al. [22], teachers would not necessarily exhibit helping behavior in a trustful environment, unless they are confident and with adequate skills in helping others.

The moderating role of collective efficacy on the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and OCB is an intriguing result of this study. As speculated, the strength of the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and OCB is stronger in a high collective efficacy environment than low collective efficacy environment. Hence, one of the valuable contributions of this study is it extends the literature on teacher self-efficacy and OCB. Teachers with high self-efficacy are more eager to support others if they share a common bond of interest and belief in their conjoint capability to achieve their common goal [40, 92, 93]. In contrast, low collective efficacy indicates a lack of cooperative and supportive group dynamics, which can result in negative emotions among teachers, thus reducing their desire to engage in OCB even if they believe in their abilities. The adverse relationship between teacher self-efficacy and OCB when collective efficacy is low provided an interesting insight. This further reinforces the argument that collective efficacy is an important asset of a school [73] as it is a condition that enables teachers to leverage their self-efficacy and demonstrate extra-role behavior. On the other hand, there is no moderating effect of collective efficacy on the relationship between trust in colleagues and OCB. This demonstrates that regardless of high or low degree of collective efficacy environment, teachers would engage themselves to help those who always show truthfulness and sincerity [51].

Theoretical implication

Several implications can be inferred based on the research findings. First, this study examined the mediating effect of teacher self-efficacy on the relationship between trust in colleague and OCB. The results showed that a partial mediation exists on the proposed mediating path. Thus, we can treat teacher self-efficacy as a complementary construct when explaining the relationship between trust in colleague and OCB. This implies that trust in colleague can influence OCB directly as well as influence through teacher self-efficacy on OCB.

Next, this study also inferred that collective efficacy could be treated as a moderator. Past studies have examined collective efficacy as an antecedent and as an outcome variable of OCB, but the research that treats collective efficacy as a moderator is sparse. Thus, this study offered a valuable contribution by affirming that collective efficacy is able to foster a positive interpersonal climate of cooperation among school members. That is, the perception of low collective efficacy would undermine the development of a supportive work environment in the school, thus adversely affecting teachers’ ability to handle challenging projects and achieve the common school objectives [94].

Practical implications

Two practical implications can be derived from the findings of this study. First, school management should actively organize several programs to enhance and promote a trusting atmosphere in the school workplace. The mean score for trust in colleagues is the lowest as compared with other constructs (mean = 3.62). Thus, it is recommended that school management should arrange a socialization program more regularly for existing teachers as well as newcomers or newly assigned teachers to the group [95]. Homans [96] indicates that a positive socialization experience and a forum for employees to interact with each other could strengthen peer relationships and eventually encourage trusting behavior. During the socialization program, teachers and newcomers are being informed with the group expectation and familiarize with the group members before they could work together effectively to accomplish the group objective [97].

Second, the finding revealed that efficacy: teacher self-efficacy and collective efficacy are one of the crucial elements to motivate teachers to exhibit citizenship behavior. Teacher self-efficacy could be improved through the development of the four primary sources of efficacy: mastery experience, vicarious experience, social persuasion, and affective states [48]. Mastery experience could be enhanced by implementing and building a culture of recognition, either monetary or non-monetary. This could be a form of motivation, engage and make them feel special and further improve their self-confidence. Whereas for vicarious experience, teachers are given opportunities to observe and understand how a top performer provides their secret recipe for achieving high performance. Next, teachers are also encouraged to update their knowledge and skills by attending regular workshops and trainings, thereby improving their ability to perform critical tasks [1]. For social persuasion, every team leader or principal played an important role by acting as a positive persuader which to convince and motivate team members to believe in their self-capability as well as conjoint capabilities in order to achieve the school goal. Lastly, for affective states, it is very common that teachers may face failure and disappointment in their job performance. This would influence teachers’ emotions negatively and discourage them to strive harder and work energetically. Therefore, a wellness program should be offered to teachers including stress management, time management, and fitness program, health management.

Limitations and future research

The first limitation of this study was its reliance on cross-sectional data which does not permit causal inferences. In the future, a more comprehensive longitudinal design approach should be adopted to establish sufficient causal relationships. Second, this study was conducted in the context of public schools, thus the findings cannot be generalized to private school settings. Future studies should extend the present research model to the private school context which may provide different insights to different stakeholders: school management and academics. Thirdly, since this study was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, it may not fully reflect the current organizational dynamics. Therefore, we propose that similar or more advanced studies be conducted in the post-pandemic era. Such studies could yield different results that would benefit the relevant stakeholders. Next, we suggest including responsible leadership or supportive leadership in future studies as leadership is an important source of professional learning among teachers [98]. With the support of professional learning, the efficacy level of teachers can be further enhanced, enabling them to perform OCB in the school context [99]. Lastly, while this study focused on teachers’ self-efficacy in general, future research can specifically evaluate the role of creative self-efficacy, a precursor of innovative behavior [5], and it is likely to foster voluntary initiatives and the sharing of creative teaching approaches among colleagues.

Conclusion

The present study provides significant contributions in both theoretical and practical aspects. It provides useful insights to school management and academics on the importance of promoting trust among teachers and developing self-efficacy and collective efficacy in a school context. Two key contributions are highlighted in this study: (1) teacher self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between trust in colleague and OCB and (2) collective efficacy significantly mediates the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and OCB. The current study concludes that trust and efficacy should not be neglected if we intend to ingrain the long-standing of helping attitudes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due the data is required to be kept confidentially which requested by third party but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Choong YO, Ng LP, Lau TC. Creating the path towards organizational citizenship behaviour through collective efficacy and teacher self-efficacy. Asia Pac J Educ. 2024;44(2):390–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2022.2053063.

Runhaar P, Konermann J, Sanders K. Teachers’ organisational citizenship behaviour: considering the roles of their work engagement, autonomy and leader-member exchange. Teach Teach Educ. 2013;30:99–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.10.008.

Somech A, Ron I. Promoting organizational citizenship behavior in schools: the impact of individual and organizational characteristics. Educ Adm Q. 2007;43(1):38–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X06291254.

Pan X, Chen M, Hao Z, Bi W. The effects of organizational justice on positive organizational behavior: evidence from a large-sample survey and a situational experiment. Front Psychol. 2018;8:2315. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02315.

Khan HS, Chughtai MS, Ma Z, Li M, He D. Adaptive leadership and safety citizenship behaviors in Pakistan: the roles of readiness to change, psychosocial safety climate, and proactive personality. Front Public Health. 2024;11:1298428.

Luthan F, Youssef CM. Emerging positive organizational behaviour. J Manage. 2007;33(3):321–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307300814.

Bogler R, Somech A. Psychological capital, team resources and organizational citizenship behaviour. J Psychol. 2019;153(8):784–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2019.1614515.

Chang K, Nguyen B, Cheng K-T, Kuo C-C, Lee I. HR practice, organizational commitment & citizenship behaviour: a study of primary school teachers in Taiwan. Empl. 2016;38(6):907–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-12-2015-0218.

Kasekende F, Munene JC, Otengi SO, Ntayi JM. Linking teacher competences to organizational citizenship behaviour: the role of empowerment. Int J Educ Manag. 2016;30(2):252–70. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-10-2014-0140.

Somech A, Ohayon B-E. The trickle-down effect of OCB in schools: the link between leader OCB and team OCB. J Educ Manag. 2020;58(6):629–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-03-2019-0056.

Cohen A, Eyal O. The role of organizational justice and exchange variables in determining organizational citizenship behavior among arab teachers in Israel. Psychol Stud. 2015;60(1):56–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-014-0286-2.

Kaur K, Randhawa G. Exploring the influence of supportive supervisors on organizational citizenship behaviour: linking theory to practice. IIMB Manag Rev. 2021;33:156–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2021.03.012.

Liu Y, Fu J, Pervaiz S, He Q. The impact of citizenship pressure on organizational citizenship performance: a three-way interactive model. Front Psychol. 2021;12:670120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.670120.

Schwabsky N. Teachers’ individual citizenship behavior (ICB): the role of optimism and trust. J Educ Adm. 2014;52(1):37–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-08-2012-0092.

Oplatka I. Understanding teacher entrepreneurship in the globalized society: some lessons from self-starter Israeli school teachers in road safety education. J Enterprising Communities: People Places Glob Econ. 2014;8(1):20–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-06-2013-0016.

Choong YO, Ng LP, Seow AN, Lau TC. Organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior: does teacher collective efficacy matter? Curr Psychol. 2024;43(14):12839–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05348-9.

Oplatka I. Organizational citizenship behavior in teaching: the consequences for teachers, pupils, and the school. Int J Educ Manag. 2009;23(5):375–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540910970476.

DiPaola MF, Tarter CJ, Hoy WK. Measuring organizational citizenship in schools: the OCB Scale. In: Hoy WK, Miskel C, editors. Essential ideas for the reform of American schools. Greenwich, CT: Information Age; 2007. pp. 227–50.

Oplatka I. The principal’s role in promoting teachers’ extra-role behaviors: some insights from road-safety education. Leadersh Policy Sch. 2013;12(4):420–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2013.847461.

Nguyen D, Ng D. Teacher collaboration for change: sharing, improving, and spreading. In Leadership for Professional Learning 2022 Dec 26 (pp. 178–91). Routledge.

Aslam MZ, Fateh A, Omar S, Nazri M. The role of initiative climate as a resource caravan passageway in developing proactive service performance. Asia-Pac J Bus Adm. 2022;14(4):691–705. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJBA-09-2021-0454.

Choong YO, Ng LP, Seow AN, Tan CE. The role of teachers’ self-efficacy between trust and organisational citizenship behaviour among secondary school teachers. Pers Rev. 2020;49(3):864–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2018-0434.

Barzoki AS, Rezaei A. Relationship between perceived organizational support, organizational citizenship behaviour, organizational trust and turnover intentions: an empirical case study. Int J Prod Qual Manag. 2017;21(3):273–99. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPQM.2017.084456.

Zhang L, Jiang H, Jin T. Leader-member exchange and organisational citizenship behaviour: the mediating and moderating effects of role ambiguity. J Psychol Afr. 2020;30(1):17–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2020.1721948.

Somech A, Ohayon BE. The trickle-down effect of OCB in schools: the link between leader OCB and team OCB. J Educ Adm. 2020;58(6):629–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-03-2019-0056.

Sendjaya S, Pekerti AA, Cooper BK, Zhu CJ. Fostering organizational citizenship behavior in Asia: the mediating roles of trust and job satisfaction. In: Sendjaya S, editor. Leading for high performance in Asia. Singapore: Springer; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6074-9_1. Nature Singapore Ptd Ltd.

Zheng X, Yin H, Liu Y, Ke Z. Effects of leadership practices on professional learning communities: the mediating role of trust in colleagues. Asia Pac Educ Rev. 2016;17:521–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-016-9438-5.

Barbaranelli C, Paciello M, Biagioli V, Fida R, Tramontano C. Positivity and behaviour: the mediating role of self-efficacy in organisational and educational settings. J Happiness Stud. 2019;20(3):707–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9972-4.

Barni D, Danioni F, Benevene P. Teachers’ self-efficacy: the role of personal values and motivations for teaching. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1645. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01645.

Bottery M. The challenges of educational leadership. Sage; 2004.

Choong YO, Jamal NY, Hamidah Y, Seow AN. The mediating effect of trust on the dimensionality of organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior amongst teachers in Malaysia. Educ Psychol. 2018;38(8):1010–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1426836.

Huang S, Yin H, Lv L. Job characteristics and teacher well-being: the mediation of teacher self-monitoring and teacher self-efficacy. Educ Psychol. 2019;39(3):313–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1543855.

Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001 Feb;52:1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1.

Zheng X, Hall R, Schyns B. Investigating follower felt trust from a social cognitive perspective. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2019;28(6):873–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1678588.

Skaalvik EM, Skaalvik S. Teacher self-efficacy and collective teacher efficacy: relations with perceived job resources and job demands, feeling job resources and job demands, feeling of belonging, and teacher engagement. Creat Educ. 2019;10(7):1400–24. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2019.107104.

Meyer A, Richter D, Hartung-Beck V. The relationship between principal leadership and teacher collaboration: investigating the mediating effect of teachers’ collective efficacy. Educ Manag Adm Leadersh. 2022;50(4):593–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220945698.

Cansoy R, Parlar H, Polatcan M. Collective teacher efficacy as a mediator in the relationship between instructional leadership and teacher commitment. Int J Leadersh Educ. 2022;25(6):900–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2019.1708470.

Choong YO, Jamal NY, Hamidah Y. The relationship between collective efficacy and organizational citizenship behavior among teachers in Malaysia. Pertanika J Soc Sci Humanit. 2017;25(s):41–50.

Stephanou G, Oikonomou A. Teacher emotions in primary and secondary education: effects of self-efficacy and collective-efficacy, and problem-solving appraisal as a moderating mechanism. Psychol. 2018;9:820–75. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2018.94053.

Lev S, Koslowsky M. Moderating the collective and self-efficacy relationship. J Educ Adm. 2009;47(4):452–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230910967437.

Cropanzano R, Mitchell MS. Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J Manag. 2005;31(6):874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602.

Shore L, Coyle-Shapiro J, Chen X, Tetrick L. Social exchange in work settings: content, process, and mixed models. Manag Organ Rev. 2009;5(3):289–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2009.00158.x.

Coyle-Shapiro JA-M, Kessler I. The employment relationship in the U.K. public sector: a psychological contract perspective. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2003;13(2):213–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpart/mug018.

Wu W-L, Lee Y-C. Empowering group leaders encourages knowledge sharing: integrating the social exchange theory and positive organizational behavior perspective. J Knowl Manag. 2017;21(2):474–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-08-2016-0318.

Bandura A. Personal and collective efficacy in human adaptation and change. In Advances in psychological science, Vol. 1. Social, personal, and cultural aspects 1998 (pp. 51–71). Psychology Press/Erlbaum (UK) Taylor & Francis.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. W.H. Freeman; 2017.

Goddard RD. Collective efficacy: a neglected construct in the study of schools and student achievement. J Educ Psychol. 2001;93(3):467–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.93.3.467.

Goddard RD, Goddard YL. A multilevel analysis of the relationship between teacher and collective efficacy in urban schools. Teach Teach Educ. 2001;17:807–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00032-4.

Schechter C, Tschannen-Moran M. Teachers’ sense of collective efficacy: an international view. Int J Educ Manag. 2006;20(6):480–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540610683720.

Tschannen-Moran M. Trust matters: Leadership for successful schools. Jossey-Bass; 2004.

Thomsen M, Karsten S, Oort FJ. Distance in schools: the influence of psychological and structural distance from management on teachers’ trust in management, organizational commitment, and organisational citizenship behavior. Sch Eff Sch Improv. 2016;27(4):594–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2016.1158193.

Choong YO, Lau LT, Ng LP. Collective efficacy among schoolteachers: influences on the relationship between Trust and Organisational Citizenship Behaviour. J Psychol Afr. 2023;33(6):594–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2023.2279373.

Choong YO, Ng LP. The effects of trust on efficacy among teachers: the role of organizational citizenship behaviour as a mediator. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(22):19087–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03067-1.

Edwards-Groves C, Grootenboer P, Ronnerman K. Facilitating a culture of relational trust in school-based action research: recognizing the role of middle leaders. Educ Action Res. 2016;24(3):369–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2015.1131175.

Khan HS, Guangshang Y, Chughtai MS, Cristofaro M. Effect of supervisor-subordinate Guanxi on employees work behavior: an empirical dynamic framework. J Innov Knowl. 2023;8(2):100360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2023.100360.

Chughtai MS, Khan HSUD. Knowledge oriented leadership and employees’ innovative performance: a moderated mediation model. Curr Psychol. 2024;43(4):3426–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04502-7.

Tschannen-Moran M, Hoy WA, Hoy WK. Teacher efficacy: its meaning and measure. Rev Educ Res. 1998;68:202–48. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543068002202.

Yin H, Huang S, Lee JCK. Choose your strategy wisely: examining the relationships between emotional labor in teaching and teacher efficacy in Hong Kong primary schools. Teach Teach Educ. 2017;66:127–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.04.006.

Bandura A. On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited [Editorial]. J Manag. 2012;38(1):9–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311410606.

Ford TG, Lavigne AL, Fiegener AM, Si S. Understanding district support for leader development and success in the accountability era: a review of the literature using social-cognitive theories of motivation. Rev Educ Res. 2020;90(2):264–307. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319899723.

Lawson GM, Owens JS, Mandell DS, Tavlin S, Rufe S, So A, Power TJ. Barriers and facilitators to teachers’ use of behavioral classroom interventions. School Mental Health. 2022;14(4):844–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-022-09524-3.

Ma K, Chutiyami M, Nicoll S. Transitioning into the first year of teaching: changes and sources of teacher self-efficacy. Aust Educ Res. 2022;49(5):943–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00481-5.

Dybowski C, Sehner S, Harendza S. Influence of motivation, self-efficacy and situational factors on the teaching quality of clinical educators. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0923-2.

Jumani NB, Malik S. Promoting teachers’ leadership through autonomy and accountability. In: Amzat I, Valdez N, editors. (Ed.s), Teacher empowerment toward professional development and practices. Singapore: Springer; 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4151-8_2.

Soto M, Rokas O. Self-efficacy and job satisfaction as antecedents of citizenship behaviour in private schools. Int J Manag Educ. 2019;13(1):82–96. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMIE.2019.10016607.

Bandura A. Going global with social cognitive theory: from prospect to paydirt. In: Donaldson SI, Berger DE, Pezdek K, editors. Ed.s), Applied psychology: new frontiers and rewarding careers. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. pp. 53–79.

Paramasivam GM. Role of self-efficacy and family supportive organizational perceptions in teachers’ organizational citizenship behavior: a study on engineering college teachers in India. Asian Educ Dev Stud. 2015;4(4):2046–3162. https://doi.org/10.1108/aeds-01-2015-0001.

Yin H, Tam WW, Lau E. Examining the relationships between teachers’ affective states, self-efficacy, and teacher-child relationships in kindergartens: an integration of social cognitive theory and positive psychology. Stud Educ Eval. 2022;74:101188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2022.101188.

Bogler R, Somech A. Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) above and beyond: teachers’ OCB during COVID-19. Teach Teach Educ. 2023;130:104183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104183.

Parhamnia F, Farahian M, Rajabi Y. Knowledge sharing and self-efficacy in an EFL context: the mediating effect of creativity. Glob Knowl Mem Commu. 2022;71(4/5):293–321.

Guidetti G, Viotti S, Bruno A, Converso D. Teachers work ability: a study of relationships between collective efficacy and self-efficacy beliefs. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2018;11:197–206. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S157850.

Lee YH, Littles C. The more the merrier? The effects of system-aggregated group size information on user’s efficacy and intention to participate in collective actions. Internet Res. 2021;31(1):191–207. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-10-2017-0379.

Goddard RD, LoGerfo L, Hoy WK. High school accountability: the role of perceived collective efficacy. Educ Policy. 2004;18(3):403–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904804265066.

Mellahi K, Harris LC. Response rates in business and management research: an overview of current practice and suggestions for future direction. Br J Manag. 2016;27(2):426–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12154.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Model. 2007;39(2):175–91. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. Sage; 2017.

Hoy WK, Tschnannen-Moran M. The conceptualisation and measurement of faculty trust in schools. In: Hoy WK, Miskel C, editors. Ed.s), studies in leading and Organizing Schools. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing; 2003. pp. 181–207.

Gibson S, Dembo M. Teacher efficacy: a construct validation. J Educ Psychol. 1984;76(4):569–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.76.4.569.

Goddard RD. A theoretical and empirical analysis of the measurement of collective efficacy: the development of a short form. Educ Psychol Meas. 2002;62(1):97–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316440206200100.

Dipaola MF, Tschannen-Moran M. Organizational citizenship behavior in schools and its relationship to school climate. J Sch Leadersh. 2001;11:424–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/10526846010110050.

Marinova SV, Cao X, Park H. Constructive organizational values climate and organizational citizenship behavior: a configurational view. J Manag. 2019;45(5):2047–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318755301.

Caesens G, Stinglhamber F. The relationship between perceived organizational support and work engagement: the role of self-efficacy and its outcomes. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2014;64(5):259–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2014.08.002.

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev. 2019;31(1):2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203.

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Kock N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int J e-Collaboration. 2015;11(4):1–0. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101.

Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press; 2006.

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Acad Mark Sci Rev. 2015;43(1):115–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8.

Zhao X, Lynch JG, Chen Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J Consum Res. 2010;37(2):197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587.

Tschannen-Moran M, Hoy WK. A multidisciplinary analysis of the nature, meaning, and measurement of trust. Rev Educ Res. 2000;70(4):547–93. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070004547.

Ng TWH, Lucianetti L. Within-individual increases in innovative behavior and creative, persuasion, and change self-efficacy over time: a social–cognitive theory perspective. J Appl Psychol. 2016;101(1):14–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000029.

Hoogsteen TJ. Collective efficacy: toward a new narrative of its development and role in achievement. Palgrave Commun 2020 Jan 7; 6(2) https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0381-z

Zhang Z, Lee JC, Yin H, Yang X. Doubly latent multilevel analysis of the relationship among collective teacher efficacy, school support, and organizational commitment. Front Psychol. 2023;13:1042798. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1042798.

Tucker MK, Jimmieson NL, Oei TP. The relevance of shared experiences: a multi-level study of collective efficacy as a moderator of job control in the stressor-strain relationship. Work Stress. 2013;27(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2013.772356.

van der Werff L, Buckley F. Getting to know you: a longitudinal examination of trust cues and trust development during socialization. J Manag. 2017;43(3):742–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314543475.

Homans GC. The Human Group. Harcourt, Brace; 1950.

De Vos A, Buyens D, Schalk R. Psychological contract development during organizational socialization: adaptation to reality and the role of reciprocity. J Organ Behav. 2013;24(5):537–99. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.205.

Chan PY, Cheah PK, Choong YO. Faculty trust and self-efficacy among teachers: the mediating role of professional learning in Malaysian national school. Int J Learn Divers Identities. 2024;31(1):233–47.

Khan HS, Li P, Chughtai MS, Mushtaq MT, Zeng X. The role of knowledge sharing and creative self-efficacy on the self-leadership and innovative work behavior relationship. J Innov Knowl. 2023;8(4):100441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2023.100441.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman for the support.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr Choong is responsible for the introduction, result reporting, discussion, implications, and conclusion.Dr Ng is responsible for the literature review, research methodology, and language editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by UTAR Scientific and Ethical Review Committee at Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman on 25 February 2019 with reference number U/SERC/36/2019. The study’s method was carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The minors are not included in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choong, YO., Ng, LP. Shaping teachers’ organizational citizenship behavior through self-efficacy and trust in colleagues: moderating role of collective efficacy. BMC Psychol 12, 532 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-02050-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-02050-8