Abstract

Background

In recent years, there has been growing interest in exploring ways to facilitate positive psychological dispositions, including resilience. The goal of the present study was to explore the possibility that trait mindfulness facilitates attachment security and thus enhances resilience.

Methods

We conducted two studies based on cross-sectional surveys. In Study 1, data of 207 students studying in Japan was collected. In Study 2, we used a different sample of 203 participants and different measurements to replicate the findings of Study 1.

Results

The results of Study 1 revealed that mindfulness positively predicted resilience, while attachment anxiety and avoidance were mediators between mindfulness and resilience. The results of Study 2 showed that mindfulness positively predicted resilience, and the mediating effect of attachment avoidance was significant, but the mediating effect of attachment anxiety was not significant.

Conclusions

It is possible to facilitate attachment security through cultivating trait mindfulness, and in this way, resilience could be enhanced. The effect of different components of mindfulness on attachment and resilience requires further studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With the development of positive psychology [1], there is growing attention to enhancing human positive psychological traits, such as resilience [2]. Though studies have found that mindfulness is a promising variation to facilitate resilience [3], the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. From the information processing theory of mindfulness [4], mindful individuals may decrease attachment insecurity through increasing conscious awareness of automatic responses to threatening cues of intimate relationships. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to explore the possibility that trait mindfulness is associated with resilience through attachment security, which is indicated by low attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety.

Resilience can be defined as the capacity to maintain or recover high well-being when faced with adverse circumstances [5], and Oshio et al. [6] emphasize the mental recovery function of resilience, including three factors: emotion regulation, novelty seeking and positive future orientation. Resilience is not genetically determined [7], which means it is possible to promote individual resilience by intervention. Previous studies have unraveled the positive psychological outcomes of resilience, such as higher self-compassion [8], higher levels of happiness, and life satisfaction [9, 10]. Especially, resilience has been proved to be a protective factor of psychological health during the crisis of COVID-19 across countries [11,12,13]. Therefore, it is meaningful to explore methods of facilitating resilience.

There is evidence that those who tend to pay attention to their moment-to-moment experience with a non-judgment attitude have a higher level of resilience [14]. Mindfulness could be regarded as enhanced attention to, and awareness of current experience or present reality [15]. Baer et al. [16] proposed a five-facet mindfulness model, including description, observation, nonreactivity, nonjudgement, and acting with awareness. Furthermore, there is evidence indicates that trait mindfulness could be enhanced through training repeatedly [17]. Existing literature shows that mindfulness training could promote resilience [18,19,20], while trait mindfulness is a predictor of resilience of different samples, such as homeless people [21], salespeople [22] and nursing students [23]. However, the underlying mechanism between trait mindfulness and resilience remains unclear.

Attachment refers to the affectional bond formed between an infant and caregivers during the early years of life [24]. Moreover, attachment also has an influence on adulthood [25]. Adult attachment can be divided into two dimensions of attachment insecurity: attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety [26]. Attachment avoidance refers to the extent to which a person distrusts intimate partners’ good intention and try to ignore their attachment needs of themselves to maintain their independence, while attachment anxiety refers to the degree to which a person worries about being abandoned by their intimate partner. People who score highly on either of these two dimensions are regarded as being insecurely attached.

As forementioned, mindfulness is associated with resilience [14, 18,19,20,21,22,23] and attachment security is significantly correlated with both resilience and mindfulness [27,28,29,30]. From the information processing theory of mindfulness [4], mindful individuals may decrease attachment insecurity through increasing conscious awareness of automatic responses to threatening cues of intimate relationships. Shapiro et al. [31] also pointed out that reperceiving is the meta mechanism of mindfulness, which suggested through mindfulness, one could witness rather than be immersed in their narrative of life story. These refer to that one could shift into the observer of their experience, being able to consciously choose their behaviors, facilitating more adaptive behaviors which are beneficial to resilience. Several studies suggest that attachment could be the mediator between mindfulness and positive psychological outcomes, such as marital satisfaction [32] and stress responses to conflict [33].

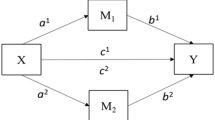

Therefore, the goal of the present study was to test the hypothesis that mindfulness is associated with resilience, and attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety were meditators of the relationship between mindfulness and resilience.

Hypothesis 1

Mindfulness is positively associated with resilience.

Hypothesis 2

Attachment avoidance independently mediates the relationship between mindfulness and resilience.

Hypothesis 3

Attachment anxiety independently mediates the relationship between mindfulness and resilience.

Two studies were conducted to test the hypotheses above. In Study 1, data were collected from 207 participants, but it mixed Chinese and Japanese participants. Measurements were burdensome, containing 83 items in total. Moreover, 6 items in the Japanese version of the Adolescent Resilience Scale (ARS) and 10 items in the Chinese version of Experience of the Experiences in Close Relationships Inventory (ECR) were deleted to keep the Japanese version of measurements and the Chinese version of measurements identical in items. These limitations potentially had a negative impact on results. To deal with these limitations, Study 2 was conducted with Japanese participants only, and shorter measurements.

Study 1

Methods

Participants

Study 1 was a cross-sectional survey. Two hundred and thirty-five students studying in Tokyo took part in Study 1. However, only 207 students correctly answered the attention check test, being regarded as valid data. Among the participants, 51.7% were Japanese, 56% were females (Mage = 21.52 years, SD = 2.85 years), including 107 Japanese students studying in local Universities (freshmen to seniors; 75.7% females, Mage = 19.97 years, SD = 1.34) and 100 Chinese international students studying in Japan (from Japanese language schools and Universities; 52% females, Mage = 23.17 years, SD = 3.10). Because of the coronavirus, we took advantage of online survey websites to deliver measurements and to collect data, Google Form for Japanese participants, and Wen Juan Xing for Chinese participants. These two websites are similar in appearance, though subtly different in colors. We send the Japanese version of measurements to Japanese participants, and the Chinese version of measurements to Chinese participants, because it was convenient for participants to understand their mother language, which could lead to more trustable results. Considering that mindfulness meditation experience may have an impact on effect sizes of the relationship between mindfulness and attachment [34], the experience of mindfulness and meditation training was also asked and was controlled in regression analysis and mediation analysis. According to the self-report, 28.5% of participants have experience with mindfulness training.

Measurements

Demographic variables

Gender, age, nationality, and the experience of mindfulness training were collected as the demographic variables.

Attachment

For Japanese participants, the Japanese version of the Experiences in Close Relationships Inventory (ECR) developed by Nakao and Kato [35] was used to measure attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance of adult attachment. According to ECR, there are 26 items in total, with 9 items for attachment anxiety and 17 items for attachment avoidance. For Chinese participants, the Chinese version of the Experiences in Close Relationships Inventory (ECR) developed by Li and Kato [36] was utilized to measure attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance of adult attachment. To keep the same with the Japanese version, 10 items only existed in the Chinese version were deleted. In both the Japanese version and the Chinese version, each statement used a 7-point Likert-type scale.

Mindfulness

We used the Japanese version of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) to measure the level of dispositional mindfulness, which was translated by Sugiura et al. [37]. The number of items is 39, and it includes 5 factors: observation, description, non-judgment, non-reaction, and act with awareness. Deng et al. [38] Chinese version of FFMQ was used to measure the level of dispositional mindfulness of Chinese participants. The number of items is 39. In both the Japanese version and the Chinese version, each statement used a 5-point Likert-type scale.

Resilience

We used Adolescent Resilience Scale to measure the resilience (ARS) of Japanese participants, which was developed by Oshio et al. [6]. The Chinese version of the Adolescent Resilience Scale was used for Chinese participants, and it was developed by Matsuda et al. [39]. In the Chinese version, there are 15 items on this scale, and it includes three factors: Positive Future Orientation (PFO), Novelty Seeking (NS), Emotional Regulation (ER). To keep the Japanese version the same as the Chinese version, we deleted six items that only exist in the Japanese version. In both the Chinese version and the Japanese version, each statement used a 5-point Likert-type scale.

Attention check test

Because the attitude and attention of participants could change during the period of filling the measurement [40], we set three check questions to ensure the validation of collected data and to recognize the random answer of participants. The check tests were respectively ‘Please choose 3’, ‘1 + 4 = ?’, ‘Please choose 2’.

Results

Data analysis was conducted by using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21 and the PROCESS Macro for SPSS Version 3.5 [41].

Descriptive statistics

Because all data in Study 1 were collected through self-report measurements, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test to examine the common method bias before the data analysis [52]. All subscales of mindfulness, resilience, and attachment were subjected to exploratory analysis, and the unrotated factor solution was examined to determine the number of factors that are necessary to account for the overall variance. This procedure suggested there was no single factor that accounted for the majority of the covariance among the variables (Facor1 accounted for 19.451% of the covariance).

Table 1 reports the Cronbach αs and descriptive statistics for the variables used in Study 1, and Tables 2 and 3 reports the bivariate relationships for variables used in Study 1. The results showed that there were significant correlations between attachment anxiety and mindfulness (r = − .36, p < .001), attachment avoidance and mindfulness (r = − .23, p < .01), attachment anxiety and resilience (r = − .23, p < .01), attachment avoidance and resilience (r = − .22, p < .01), and mindfulness and resilience (r = .21, p < .01).

In addition, the Cronbach α of the non-reaction subscale of FFMQ was .58, .65, and .48, and the Cronbach α of the emotion regulation subscale of Chinese version ARS was .60.

Conditional process model

We conducted the regression model with mindfulness as the independent variable, attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance as mediating variables, resilience as the dependent variable, and nation and experience of mindfulness training as control variables (Table 4) to test the conditional process models [42]. According to the results, variables put together accounted for 16.2% of the total variance of resilience.

We used 5000 bootstrap samples to test the mediating effect of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance in relation to mindfulness and resilience (Table 5). The result showed that both the mediating effects of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance were significant, 95% bootstrap confidence interval of attachment anxiety was (.003, .080), Bootstrap SE = .020, and 95% bootstrap confidence interval of attachment avoidance was (.004, .048), Bootstrap SE = .012, and the relative mediating effect was 32.174% and 19.130% respectively. The direct effect was not significant, and the 95% bootstrap confidence interval was (− .042, .154), Bootstrap SE = .050.

Discussion

Common method bias and correlations

No problematic common method bias was found in Study 1, and all measurements in Study 1 except the nonreaction subscale of in Japanese and Chinese version FFMQ, and emotion regulation subscale in Chinese version ARS had appropriate reliability.

Mindfulness correlated with attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, and resilience. These findings are consistent with previous research [23, 43]. And we also found that resilience correlated with attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance.

Test of hypotheses

Bootstrap mediating effect analysis showed that mindfulness was positively associated with resilience (hypothesis 1), and this relationship was mediated by both attachment avoidance (hypothesis 2) and attachment anxiety (hypothesis 3). These results approved the idea that attachment facilitates a resilient mind [44], suggesting that mindful individuals tend to be more securely attached, that is, lower scores in both attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety, which leads to a better ability to recover in the face of suffering. Align with the idea of information process theory [4], the tendency to take a mindful decentered perspective may be associated with increasing conscious awareness of automatic responses to interpersonal information that could trigger the hyperactivation of attachment anxiety and deactivation of attachment avoidance. And according to the model proposed by Shapiro et al. [31], mindful individuals could keep an intimate distance from their thoughts and feelings without believing in them through the conscious awareness of automatic responses. This conscious awareness of automatic responses would make it possible to revise their internal working model, which may further facilitate resilience.

Some limitations exist in Study 1. First, as mentioned before, the Cronbach α of the nonreaction subscale of in Japanese and Chinese version FFMQ, and the emotion regulation subscale in Chinese version ARS were relatively low, therefore one may cast doubts on whether the data we measured was reliable. This may be partly caused by the items we deleted. Second, we only used cross-section data in Study 1, which cannot reveal the causal relationship. Third, Japanese participants and Chinese participants were mixed for the reason that during the coronavirus period, it was hard to collect enough data of a specific sample, though we send the mother language version of the measurements to participants, it could still be a confounding variable.

Study 2

Considering the limitation mentioned in Study 1, Study 2 was conducted to examine the findings of Study 1 with two changes. First, we collected a different Japanese-only sample. Second, we utilized shorter Japanese version measurements.

Methods

Participants

Study 2 was also a cross-sectional survey. Two hundred and eighteen participants were recruited in Tokyo, Japan. Among 218 participants, 203 participants (74 males, 125 females, and 4 others; Mage = 20.72 years, SD = 4.78) answered the attention check test correctly, being regarded as valid data. The University Ethical Committee approved this study.

Measurements

Demographic variables

Gender and age were collected as the demographic variables.

Attachment

The nine-item Japanese version of Experience of Close Relationship-Relationship Structure (ECR-RS) [45] was utilized to measure attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance. Participants answer the items on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = completely true). Mean scores were calculated as attachment anxiety score and attachment avoidance score.

Mindfulness

The fifteen-item Japanese version of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) was utilized to measure mindfulness, which was developed by Fujino et al. [46]. Participants answer the items on a 6-point scale (6 = not at all, 1 = almost always). The mean score of every item was calculated as a mindfulness score.

Resilience

Twenty-five-item Scale for Resilience Scale for Students developed by Saito and Okayasu [47] were utilized to measure resilience. Participants answer the items on a four-point scale (1 = not at all, 4 = completely true). Mean scores were calculated as resilience scores.

Attention check test

Because the attitude and attention of participants could change during the period of filling the measurement [40], ‘Please choose 3’, and ‘Please choose 2’ were asked as attention tests. Participants whose answers were wrong would be regarded as invalid data and thus got deleted.

Results

Data analysis was conducted by using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21 and the PROCESS Macro for SPSS Version 3.5 [41], the same as Study 1.

Descriptive statistics

Considering all data in study 2 were collected through self-report measurements like in Study 1, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test to examine the common method bias before the data analysis [52]. Measurements of mindfulness, resilience, and attachment were subjected to exploratory analysis, and the unrotated factor solution was examined to determine the number of factors that are necessary to account for the overall variance. This procedure suggested there was no single factor that accounted for the majority of the covariance among the variables (Facor1 accounted for 18.909% of the covariance).

Table 6 reports the Cronbach α and descriptive statistics for the variables used in Study 2, and Tables 7 and 8 report the bivariate relationships for variables used in Study 2. The results showed that there were significant correlations between mindfulness and attachment anxiety (r = − .200, p < .01), mindfulness and attachment avoidance (r = − .245, p < .001), attachment anxiety and resilience (r = − .269, p < .001), attachment avoidance and resilience (r = − .521, p < .001), and mindfulness and resilience (r = .268, p < .001). In addition, the Cronbach α of every measurement ranged from .791 to .913.

Conditional process model

We conducted the regression model with mindfulness as the independent variable, attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance as mediating variables, resilience as the dependent variable, and gender and age as control variables (Table 4) to test the conditional process models [42]. According to the results, variables put together accounted for 16.2% of the total variance of resilience.

Five thousand bootstrap samples were utilized to test the mediating effect of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance in the relationship between mindfulness and resilience (Table 9). The result showed that the mediating effect of attachment avoidance was significant, 95% bootstrap confidence interval of attachment avoidance was (.024, .105), Bootstrap SE = .020. However, the mediating effect of attachment anxiety was not significant, and the 95% bootstrap confidence interval of attachment anxiety was (− .004, .032), Bootstrap SE = .012. The relative mediating effect of attachment avoidance was 42.361%. The direct effect was significant, and the 95% bootstrap confidence interval was (.006, .138), Bootstrap SE = .034.

Discussion

The main aim of Study 2 was to replicate the findings of Study 1 through a different Japanese-only sample and different shorter measurements. For this purpose, data of 203 Japanese participants were collected and analyzed. We successfully replicated the findings that mindfulness was positively associated with resilience (hypothesis 1), and attachment avoidance mediated the relationship between mindfulness and resilience (hypothesis 2). However, we failed to replicate the finding that attachment anxiety could mediate the relationship between mindfulness and resilience.

Common method bias and correlations

There was no problematic common method bias found in Study 2, and all measurements in Study were of good reliability.

Mindfulness correlated with attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, and resilience. And we also found that resilience correlated with attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety. These findings are not only consistent with previous research [23, 43], but also replicated the findings of Study 1.

Test of hypotheses

As mentioned above, Study 2 once again indicated that mindfulness is positively associated with resilience (hypothesis 1), and the mediating role of attachment avoidance between mindfulness and resilience was significant (hypothesis 2). However, the mediating role of attachment anxiety between mindfulness and resilience was not significant, that is, hypothesis 2 was not supported by Study 2. The reason might partly be that the measurements utilized in Study 2 were different from measurements in Study 1, especially the measurement of mindfulness. According to Shapiro et al. [31], mindfulness consists of three elements: attention, intention, and attitude. In Study 1, we used the FFMQ, which is a five-facet model of mindfulness, including description, observation, nonreactivity, nonjudgement, and acting with awareness. However, in Study 2, we used the MAAS, which is a one-factor structure and does not measure the nuanced elements of mindfulness. According to the attachment theory, anxiously attached individuals tend to be highly aware of cues and information indicating a potential threat, while avoidantly attached individuals tend to ignore attachment needs so that they could keep their internal working models not activated [48]. Therefore, anxiously attached individuals tend to be high in mindful attention, but their attitude may not be non-judgmental, which was emphasized by the FFMQ and not measured by the MAAS. On the other hand, avoidantly attached individuals are likely to avoid paying attention to their attachment needs of themselves, which were both emphasized by FFMQ and MAAS, and thus Study 2 replicated the findings of Study 1.

General discussion

Since the end of 2019, the Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) had a severe impact on the human lifestyle, and it could be important to recognize factors associated with resilience to better cope with changes and challenges. Two cross-sectional studies were conducted to test the possibility that mindfulness facilitates resilience and test the underlying mechanism. Consistent with previous research, we found that mindfulness was positively associated with resilience [14, 18,19,20,21,22,23], both attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety were negatively associated to mindfulness and resilience in the correlation analysis [27,28,29,30]. Furthermore, attachment avoidance could be the mediator of the relationship between mindfulness and resilience. The mediating effect of attachment anxiety was found in Study 1, but not Study 2, and it may partly be due to the differences between FFMQ and MAAS. It requires further studies on the effect of different components of mindfulness on attachment.

In general, our results partly supported the information process model of mindfulness [4], suggesting that mindful individuals could notice their automatic response patterns like the internal working models of attachment, and then make a pause to choose what to do consciously, which lead to more adaptive behavior and thus facilitate resilience. Indeed, previous studies found that mindfulness is associated with adaptive affective response [49], adaptive factors [50] and adaptive development [51], and attachment is likely to be the mediator between the relationship of mindfulness and positive psychological outcomes [32, 33]. The findings of the present study suggest that during the intervention, it is effective for college students to practice mindfulness to facilitate resilience. Specifically, mindful attention is important to reduce attachment avoidance, leading to a higher level of resilience. And it is likely to be important to cultivate a non-judgmental attitude and practice various mindful skills for those who score highly in attachment anxiety to facilitate their resilience.

There are several limitations in the present study. First, though there are two studies in the present study, only self-report measurements were used. Therefore, combined methods and different resources of data are necessary for further studies. Second, to figure out the causal relationship, experiments are necessary. Third, because of the influence of COVID-19, it is hard to collect enough data of both Japanese and Chinese participants in the present study, and thus the international comparison of the relationship among mindfulness, attachment, and resilience needs to be tested in the future. Fourth, the measurements utilized for Japanese participants and Chinese participants in Study 1 were different in languages, which may have an impact on the results. Therefore, it would be helpful for future research to compare the Japanese version and Chinese version of ECR, FFMQ, and ARS to examine the cross-cultural equivalence.

Conclusions

Study 1 and Study 2 investigated the relationship between mindfulness, resilience, and attachment. Although it had several limitations, it extended the research to the factors associated with resilience. The findings indicated that mindfulness was positively associated with resilience, and attachment avoidance could mediate the relationship between mindfulness and resilience, and the role of attachment anxiety between mindfulness and resilience required further research.

Availability of data and materials

Data used during these two studies are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ARS:

-

Adolescent Resilience Scale

- ECR:

-

The Experiences in Close Relationships Inventory

- FFMQ:

-

The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire

- PFO:

-

Positive Future Orientation

- NS:

-

Novelty Seeking

- ER:

-

Emotional Regulation

- ECR-RS:

-

The Experience of Close Relationship-Relationship Structure

- MAAS:

-

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale

References

Kim H, Doiron K, Warren MA, Donaldson SI. The international landscape of positive psychology research: a systematic review. Int J Wellbeing. 2018;8(1):50–70. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v8i1.651.

Barasa E, Mbau R, Gilson L. What is resilience and how can it be nurtured? A systematic review of empirical literature on organizational resilience. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(6):491–503. https://doi.org/10.15171/IJHPM.2018.06.

Thompson RW, Arnkoff DB, Glass CR. Conceptualizing mindfulness and acceptance as components of psychological resilience to trauma. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2011;12(4):220–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838011416375.

Breslin FC, Zack M, McMain S. An information-processing analysis of mindfulness: implications for relapse prevention in the treatment of substance abuse. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2002;9(3):275–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.9.3.275.

Ryff CD, Singer B, Love GD, Essex MJ. Resilience in adulthood and later life: defining features and dynamic processes. In: Lomranz J, editor. Handbook of aging and mental health: an integrative approach. Plenum Press; 1998. p. 69–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0098-2_4.

Oshio A, Nakaya M, Kaneko H, Nagamine S. Development and validation of an adolescent resilience scale. Jpn J Couns Sci. 2002;35:57–65 (in Japanese with English abstract).

Rutter M. Resilience, competence, and coping. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31(3):205–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.001.

Bluth K, Mullarkey M, Lathren C. Self-compassion: a potential path to adolescent resilience and positive exploration. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27(9):3037–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1125-1.

Aboalshamat KT, Alsiyud AO, Al-Sayed RA, Alreddadi RS, Faqiehi SS, Almehmadi SA. The relationship between resilience, happiness, and life satisfaction in dental and medical students in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Niger J Clin Pract. 2018;21(8):1038–43.

Bajaj B, Pande N. Mediating role of resilience in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and affect as indices of subjective well-being. Personal Individ Differ. 2016;93:63–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.005.

Labrague LJ, De los Santos JAA. COVID-19 anxiety among front-line nurses: predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28(7):1653–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13121.

Luceño-Moreno L, Talavera-Velasco B, García-Albuerne Y, Martín-García J. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, levels of resilience and burnout in Spanish health personnel during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155514.

Ye Z, Yang X, Zeng C, Wang Y, Shen Z, Li X, Lin D. Resilience, social support, and coping as mediators between COVID-19-related stressful experiences and acute stress disorder among college students in China. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12211.

Sünbül ZA, Güneri OY. The relationship between mindfulness and resilience: the mediating role of self-compassion and emotion regulation in a sample of underprivileged Turkish adolescents. Personal Individ Differ. 2019;139:337–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.12.009.

Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504.

Kiken LG, Garland EL, Bluth K, Palsson OS, Gaylord SA. From a state to a trait: trajectories of state mindfulness in meditation during intervention predict changes in trait mindfulness. Personal Individ Differ. 2015;81:41–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.044.

Crowder R, Sears A. Building resilience in social workers: an exploratory study on the impacts of a mindfulness-based intervention. Aust Soc Work. 2017;70(1):17–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2016.1203965.

Denkova E, Zanesco AP, Rogers SL, Jha AP. Is resilience trainable? An initial study comparing mindfulness and relaxation training in firefighters. Psychiatry Res. 2020;285: 112794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112794.

Jha AP, Morrison AB, Parker SC, Stanley EA. Practice is protective: Mindfulness training promotes cognitive resilience in high-stress cohorts. Mindfulness. 2017;8(1):46–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0465-9.

Lu J, Potts CA, Allen RS. Homeless people’s trait mindfulness and their resilience: a mediation test on the role of inner peace and hope. J Soc Distress Homelessness. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2020.1774847.

Charoensukmongkol P, Suthatorn P. Salespeople’s trait mindfulness and emotional exhaustion: the mediating roles of optimism, resilience, and self-efficacy. Int J Serv Econ Manag. 2018;9(2):125–42. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSEM.2018.10017350.

Chamberlain D, Williams A, Stanley D, Mellor P, Cross W, Siegloff L. Dispositional mindfulness and employment status as predictors of resilience in third year nursing students: a quantitative study. Nurs Open. 2016;3(4):212–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.56.

Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: attachment, vol. 1. 2nd ed. Basic Books; 1969.

Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52:511–24. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511.

Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: an integrative overview. In: Simpson JA, Rholes WS, editors. Attachment theory and close relationships. The Guilford Press; 1998. p. 46–76.

Barcaccia B, Cervin M, Pozza A, Medvedev ON, Baiocco R, Pallini S. Mindfulness, self-compassion and attachment: a network analysis of psychopathology symptoms in adolescents. Mindfulness. 2020;11(11):2531–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01466-8.

Goodall K, Trejnowska A, Darling S. The relationship between dispositional mindfulness, attachment security and emotion regulation. Personal Individ Differ. 2012;52(5):622–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.008.

Stevenson JC, Emerson LM, Millings A. The relationship between adult attachment orientation and mindfulness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness. 2017;8(6):1438–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0733-y.

Stevenson JC, Millings A, Emerson LM. Psychological well-being and coping: the predictive value of adult attachment, dispositional mindfulness, and emotion regulation. Mindfulness. 2019;10(2):256–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0970-8.

Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, Freedman B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62(3):373–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20237.

Jones KC, Welton SR, Oliver TC, Thoburn JW. Mindfulness, spousal attachment, and marital satisfaction: a mediated model. Fam J. 2011;19(4):357–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480711417234.

Hertz RM, Laurent HK, Laurent SM. Attachment mediates effects of trait mindfulness on stress responses to conflict. Mindfulness. 2015;6(3):483–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0281-7.

Pepping CA, O’Donovan A, Davis PJ. The differential relationship between mindfulness and attachment in experienced and inexperienced meditators. Mindfulness. 2014;5(4):392–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0193-3.

Nakao T, Kato K. Constructing the Japanese version of the adult attachment style scale (ECR). Jpn J Psychol. 2004;75(2):154–9. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.75.154 (in Japanese with English abstract).

Li TG, Kato K. Measuring adult attachment: Chinese adaptation of the ECR scale. Acta Psychol Sin. 2006;38(03):399–406.

Sugiura Y, Sato A, Ito Y, Murakami H. Development and validation of the Japanese version of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire. Mindfulness. 2012;3(2):85–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0082-1.

Deng YQ, Liu XH, Rodriguez MA, Xia CY. The five facet mindfulness questionnaire: psychometric properties of the Chinese version. Mindfulness. 2011;2(2):123–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0050-9.

Matsuda T, Tsuda A, Kim E, Horiuchi S, Deng K, Yamamoto N. Development of the Chinese version of adolescent resilience scale for Chinese foreign students in Japan. Kurume Univ Psychol Res. 2012;11:15–22 (in Japanese with English abstract).

DeSimone JA, Harms PD, DeSimone AJ. Best practice recommendations for data screening. J Organ Behav. 2015;36(2):171–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1962.

Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford Publications; 2017.

Hayes AF, Rockwood NJ. Conditional process analysis: concepts, computation, and advances in the modeling of the contingencies of mechanisms. Am Behav Sci. 2020;64(1):19–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219859633.

Caldwell JG, Shaver PR. Mediators of the link between adult attachment and mindfulness. Interpers Int J Pers Relationsh. 2013;7(2):299–310. https://doi.org/10.5964/ijpr.v7i2.133.

Bender A, Ingram R. Connecting attachment style to resilience: contributions of self-care and self-efficacy. Personal Individ Differ. 2018;130:18–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.03.038.

Komura K, Murakami T, Toda K. Validation of a Japanese version of the experience in close relationship-relationship structure. Jpn J Psychol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.87.15208 (In Japanese with English abstract).

Fujino M, Kaimura S, Nomura M. Development and validation of the Japanese version of the mindful attention awareness scale using item response theory analysis. Jpn J Pers. 2015;24(1):61–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0082-1 (in Japanese with English abstract).

Saito K, Okayasu T. Development of the scale for resilience scale for students. Meiji Univ J Psycho-Sociol. 2009;5:22–32 (in Japanese with English abstract).

Mikulincer M, Shaver P. Adult attachment: structure, dynamics and change. The Guilford University Press; 2007.

Martelli AM, Chester DS, Warren Brown K, Eisenberger NI, DeWall CN. When less is more: mindfulness predicts adaptive affective responding to rejection via reduced prefrontal recruitment. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2018;13(6):648–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsy037.

Maltais M, Bouchard G, Saint-Aubin J. Mechanisms of mindfulness: the mediating roles of adaptive and maladaptive cognitive factors. Curr Psychol. 2019;38(3):846–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9665-x.

Amada NM, Shane J. Mindfulness as a promoter of adaptive development in adolescence. Adolesc Res Rev. 2019;4(1):93–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-018-0096-1.

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to show gratitude to the co-researchers and participants for their cooperation throughout the recruitment and data collection processes.

Funding

These two studies did not receive any specific grant from any funding entity in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: FY, TO; data curation: FY; formal analysis: FY; supervision: TO; writing—original draft: FY; writing—review and editing: FY, TO. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

These Two studies were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the College of Humanities and Sciences, Nihon University. Reference numbers were 02-10 for Study 1 and 02-19 for Study 2. Written informed consents were obtained from all participants in these two studies.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, F., Oka, T. The role of mindfulness and attachment security in facilitating resilience. BMC Psychol 10, 69 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00772-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00772-1