Abstract

Background

Anorexia nervosa has one of the highest mortality rates of all mental illnesses. For those who survive, less than 70% fully recover, with many going on to develop a more severe and enduring phenotype. Research now suggests that genetics plays a role in the development and persistence of anorexia nervosa. Inclusion of participants with more severe and enduring illness in genetics studies of anorexia nervosa is critical.

Objective

The primary goal of this review was to assess the inclusion of participants meeting the criteria for the severe enduring anorexia nervosa phenotype in genetics research by (1) identifying the most widely used defining criteria for severe enduring anorexia nervosa and (2) performing a review of the genetics literature to assess the inclusion of participants meeting the identified criteria.

Methods

Searches of the genetics literature from 2012 to 2023 were performed in the PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases. Publications were selected per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). The criteria used to define the severe and enduring anorexia nervosa phenotype were derived by how often they were used in the literature since 2017. The publications identified through the literature search were then assessed for inclusion of participants meeting these criteria.

Results

most prevalent criteria used to define severe enduring anorexia nervosa in the literature were an illness duration of ≥ 7 years, lack of positive response to at least two previous evidence-based treatments, a body mass index meeting the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 for extreme anorexia nervosa, and an assessment of psychological and/or behavioral severity indicating a significant impact on quality of life. There was a lack of consistent identification and inclusion of those meeting the criteria for severe enduring anorexia nervosa in the genetics literature.

Discussion

This lack of consistent identification and inclusion of patients with severe enduring anorexia nervosa in genetics research has the potential to hamper the isolation of risk loci and the development of new, more effective treatment options for patients with anorexia nervosa.

Plain English Summary

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a serious illness with a high death rate. Many of those with AN do not recover and have continuing severe psychological and physical symptoms that greatly impact their quality of life. Research has shown that genetics plays an important role, along with environment, in the development and persistence of AN. This review highlights the continued lack of consensus on defining criteria for severe and enduring AN in the literature and the continued focus on younger females with shorter illness durations in AN genetics research. Greater efforts are needed to include older participants with severe AN of longer duration in genetics research in hopes of developing more effective treatments for this underrepresented group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a devastating illness with a high mortality rate. The standardized mortality ratio (SMR) calculates whether those in a given study population are equally, more or less likely to die compared to a reference population [1]. With an estimated SMR between 5.9 and 15.9 (i.e., 6–16 times excess mortality), AN is considered one of the deadliest mental disorders [2, 3].

Studies indicate that the overall incidence rate for AN has remained relatively stable (4% female lifetime-0.3% male lifetime) since the 1970s [2, 4]. The symptomology and presentation of AN have evolved along cultural lines; however, it is not simply a manifestation of modern cultural and social pressures. Accounts of deliberate self-starvation date back to the beginning of written history [5].

Although the exact etiology of AN is still unclear, a substantial body of evidence indicates that genetics plays a considerable role [6, 7]. Genetic studies dating from the late 20th century have shown that AN is highly familial. The lifetime risk of developing AN for female relatives of individuals with AN is 11 times greater than that for female relatives of individuals without AN [8]. Heritability (h2twin) estimates from twin studies range from ∼48–74% [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. The large range in estimates may be due to the use of broader participant inclusion criteria in AN studies to increase study group size. Broadening the inclusion criteria results in a more heterogeneous sample and decreased heritability estimates, while narrowing the definition of AN yields higher and more consistent estimates [17].

Although recovery from AN is possible, for approximately 20% of affected individuals the condition takes on a more intractable phenotype [18, 19]. While AN symptoms vary from person to person, it has been suggested that a unique severe and enduring anorexia nervosa (SE-AN) subtype exists; however, aligning on clear defining criteria has proved challenging [20].

Since the 1980s, a small number of literature reviews of varying breadth and depth have been conducted in attempts to better define SE-AN. The most comprehensive to date, a 2017 review by Broomfield and colleagues identified illness duration and previous unsuccessful treatment as the criteria most often used in the literature to define AN severity [21]. A 2018 editorial by Hay and Touz, which referenced the Broomfield review, expanded the suggested criterion to include significantly diminished quality of life and narrowed the duration criterion to a minimum of three years and the therapeutic intervention exposure criterion to at least two previous evidence-based treatments [22]. In a 2021 follow-up review, with the aim of defining a neuropsychological profile for SE-AN, Bloomfield et al. identified intelligence, set-shifting and decision-making as features warranting further attention and noted that additional data are needed to align on defining severity criteria [23]. In short, there continues to be a lack of consensus on how to best define SE-AN.

Psychiatric illness is often diagnosed in a binary manner; an individual is assessed as either having the illness or not. In reality, due to their complex nature, psychiatric illnesses are better defined on a continuum [24, 25]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) often use a binary case-control design. However, as Yang et al. [26] noted, with an equal population sample size, a quantitative trait (for example, symptom severity) association study will have greater power than a case-control association study. The difference is because in a case-control study, an individual with mild symptoms is not differentiated from one with severe symptoms. Relating this to AN, there would be no differentiation between an individual who met the DSM-5 criteria for mild illness, of short duration and who was responsive to first-line treatment, and an individual who met the extreme illness criteria, with a duration of over a decade and lack of positive response to multiple treatment modalities. Delineating participants based on illness severity when performing genetic data analysis of those with AN may improve the chances of identifying significant variants.

The potential value of defining more phenotypically similar groups based on quantitative phenotypes and comorbidities in genetic studies of psychiatric illness has been demonstrated in major depressive disorder (MDD), schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) [27,28,29,30]. Individuals with more severe MDD symptoms have been found to have increased genetic risk for other psychiatric disorders [29], and polygenic risk scores (PRS) for schizophrenia correlate with symptom severity [28]. Genetic risk score (GRS), PRS and polygenic score (PGS) are the terms most often used in the literature when referring to values estimating an individual’s lifetime risk of developing a phenotype (disorder) based only on their genetics [31]. The scores are generated by combining the number of risk alleles at all the risk variants in an individual’s genome. Disease-associated risk variants are based on the latest and most comprehensive GWAS for the disorder at the time of the analysis.

Studies delineating and comparing subgroups of individuals with AN based on defined quantitative criteria may result in the discovery of rare variants associated with symptom severity, and individuals manifesting a more severe phenotype may be more likely to show higher heritability estimates and thus represent a subgroup of patients for which genetics findings may be beneficial. However, this hypothesis cannot be adequately tested to the rigorous standards required without a more precise definition of what constitutes a severe and enduring phenotype, and greater attention given to specifically identifying and including this group in genetic studies [32].

The aim of this review is to first, as an extension of the Broomfield et al. review [21], identify the criteria most widely used to describe the phenotypic severity of AN by including articles published since 2017 and, second, evaluate the genetics literature for inclusion of individuals meeting these criteria.

Methods

Delineating criteria for the severe and enduring anorexia nervosa phenotype

To better identify and delineate research participants manifesting a severe and enduring phenotype in the genetics literature, it was necessary to discern the most often used defining criteria for this subgroup of AN. The terms Anorexia Nervosa AND severe AND (Enduring OR Chronic) were used, with no year limit, to search titles and abstracts in PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Articles were also limited to human subjects.

One of the articles identified was an extensive review by Broomfield et al. of how the literature labeled and defined AN severity up to 2017 [21]. The current search was limited to articles published after the Broomfield 2017 review to focus on the most recent literature. The references were not required to be attempting to empirically define a severe or enduring anorexia nervosa phenotype. The goal was to determine how those with a longer lasting and more severe clinical presentation are currently referred to in the literature. After removing commentaries on other references, clarifications, and updates from previous studies with the same authors and criteria, redundant references, and those not referring to a severe or enduring anorexia nervosa phenotype, 37 publications remained. Of these 37 publications, there were 22 research papers (6 clinical trials, 16 studies), 4 case reports, 6 expert panel/position papers/or opinion/editorial papers, 2 literature reviews and 3 general reviews. These references are listed in Table 1, along with a book chapter [33] identified through reviewing the references of the selected papers, that was not included in the Broomfield 2017 review, bringing the total publications included to 38. The mean age, mean BMI, duration of illness in years, and history of previous treatment, as well as any other measures of illness severity, were extracted from the articles and are shown in Table 1. A second reviewer, using the RANBETWEEN function in Microsoft Excel, selected 10% of the articles at random from Table 1. to review for meeting inclusion criteria and accuracy of the data extracted.

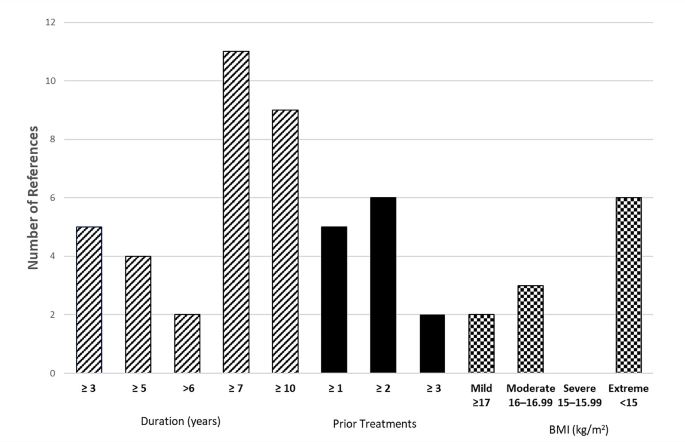

Articles were reviewed to determine which criteria are used most often in the literature in regard to the severe enduring phenotype. Specifically, articles with a central purpose of better defining a severe and or enduring/chronic AN phenotype or the need for better treatment options (for example [34, 35]), and articles including case studies or participants in one or more study groups defined as having a severe and or enduring/chronic AN phenotype (for example [36, 37]) were included. The tabulation from the Broomfield review was combined with the current total. Given that the four Dalton articles referenced the same data, they were counted as only one reference. The results are outlined in Fig. 1.

Number of references from Table 1 representing the specific duration of illness, number of previous unsuccessful treatments and body mass index (BMI) subgroups indicated either in defining severe and enduring anorexia nervosa or as inclusion criteria for participants. The totals indicated include both the references from the 2017 Broomfield review [21] and the current work

Literature review: inclusion of participants meeting the severe and enduring AN phenotype in genetics research

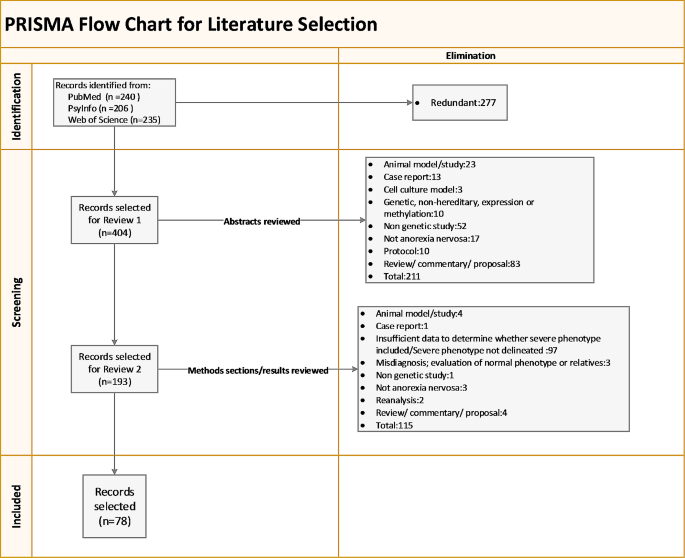

The search outlined in this section followed the process depicted in the PRISMA flow diagram [38] in Fig. 2, which captures the literature selection flow. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist was utilized [39]. The goal was to assess whether participants meeting the criteria identified as the most widely used to define a severe and enduring phenotype are being included in genetics research, and, if included, whether these participants were assessed as an independent group.

The terms Anorexia Nervosa AND (genetic OR gene OR hereditary) in titles and abstracts were used for the following searches. Articles were limited to human subjects, and review articles were excluded. The goal was to be as inclusive as possible in the initial searches of each database. The search was limited to the last decade of published literature to assess current practices in genetics research. This span of time encompasses the five years leading up to and following the identification of the first genome wide significant locus for AN [40] and the publication of Broomfield et al., both of which were published in 2017. The inclusion dates were as follows: PubMed, 1-Jan-2012 to 6-Oct-2023 (date of search); PsycINFO, 1-Jan-2012 to 10-Oct-2023 (date of search); and Web of Science, 1-Jan-2012 to 12-Oct-2023 (date of search).

Searches of PubMed, PsycINFO and Web of Science conducted with the search criteria resulted in 240, 206 and 235 hits, respectively. Titles and keywords were reviewed, and 277 articles were eliminated for redundancy (see “identification” in Fig. 2). During the first screening, the abstracts for the remaining 404 were reviewed, and 211 were eliminated for the reasons depicted in the PRISMA diagram (“Records selected for Review 1”). The remaining 193 publications progressed to the second screening.

In the second screening, noted as “Records selected for Review 2” in the PRISMA diagram, the methods sections of the remaining 193 articles were reviewed for details on age, psychological assessments, anorexia subtype, duration of illness, prior treatment history, and other indications of disease severity. Studies did not need to specifically call out a subgroup of participants as being severe and or enduring; however, those not including participant data for at least three of the following four criteria were eliminated because they did not provide adequate information for the assessment of participant phenotype severity and intractability: (1) duration of illness; (2) body mass index (BMI); (3) prior treatment history; and (4) severity as measured by one or more clinical, social, or psychological scales. This resulted in the elimination of an additional 115 articles. A total of 78 articles were ultimately included in the information extraction process; the results are presented in Table 2.

The data were extracted by reviewing both the methods and results sections of each paper for the following participant data: (1) mean duration of illness in years; (2) mean BMI in kg/m2; (3) prior treatment history; (4) and severity as measured by one or more clinical, social, or psychological scales. Participant gender, mean age, and groups of eating disorders included in the studies (i.e., AN-restricting, AN-binge purge, bulimia, binge eating) were also extracted. A second reviewer, using the RANBETWEEN function in Microsoft Excel, selected 10% of the articles at random from Table 2 to review for meeting inclusion criteria and accuracy of the data extracted.

Results

Defining severe enduring anorexia nervosa in the research literature

A review of the literature revealed that the terms severe, chronic, and enduring identified by Broomfield et al., in 2017 [21] continue to be widely used to label the more intractable AN phenotype. How these labels are defined in the literature, when they are defined, continues to vary greatly. The age of study participants, BMI, duration of illness, and previous treatment history were extracted from each reference and are recorded in Table 1.

The primary inclusion criteria presented in the articles reviewed were as follows:

-

1.

Duration:

The Broomfield review [21] identified duration as the primary criterion used to define the severe and enduring AN phenotype, and this continues to be true. Several articles reviewed included duration of illness as a criterion for inclusion in their study or clearly delineated a subgroup using duration as one criterion. The stringency of how duration was measured varied.

In their audit of care received by patients with “early stage” versus “severe and enduring” AN, Ambwani et al. [36] defined a duration of < 3 years for early stage and ≥7 years for severe and enduring AN, as recommended by Robinson et al. and Touyz et al. [41, 42]. This was also the case for Calugi et al. [43], who used ≥7 years in their study of cognitive behavioral therapy effectiveness. The patient described in the case study by Voderholzer et al. [44] had AN for seven years. In the four papers by Dalton et al. studying the impact of transcranial magnetic stimulation on severe and enduring AN, the duration inclusion criterion for study participation was ≥3 years of AN symptoms [45,46,47,48]. Whereas Knyahnytska et al. [49] included a duration of > 5 years as a criterion for treatment resistance in their insula H-coil transcranial stimulation therapy study. In the selection of a subset of participants from the Anorexia Nervosa Genetics Initiative (ANGI) to include in their assessment of the polygenic association of severity and long-term outcome in AN, Johansson et al. [50] included in their criteria for the severe enduring subtype a ≥ 5 year follow-up time, defined by the authors as years between initial registration and ANGI recruitment. Finally, in two of the three studies evaluating the effectiveness of deep brain stimulation, an illness duration of ≥ 10 years was required for participant inclusion [51, 52], with the third requiring > 7 years [53]. Case study, clinical trial and study participants included in groups indicated as manifesting a severe and enduring phenotype tended to have illness of longer duration. For example, participants in the Calugi et al. [43] study had a mean duration of 12.3(4.7 SD) years, and the three case study subjects had illness durations of 7 [44], 11 [54], 25 [55], and 26 [37] years.

Position papers, commentaries, and reviews also varied greatly in defining duration requirements. For example, in their German language case study on palliative care for severe AN, Westermair et al. [56] proposed a long duration of illness, e.g., 10 years, as a criterion, whereas Hay and Touyz [22] and Herpetz-Dahlmann [57] used a duration of > 3 years. Other authors fell between the two extremes; Bianchi et al. [58] defined severe and enduring AN participants as those who had the disorder for six years or more, and Marzola et al. [59] used a seven-year demarcation. However, these two papers also proposed that duration should not be used alone when defining AN severity. The usefulness of duration as a criterion was also questioned by Wildes et al. [60]. In an attempt to define the severe and enduring phenotype empirically, Wildes found no evidence for a chronic subgroup of AN, instead proposing that this group may be better classified on the basis of impact on quality of life and severity of injurious behaviors. As indicated in Fig. 1, a duration of 7 or more years was used most frequently, followed by 10 years.

-

2.

Severity:

Body mass index (BMI):

The DSM-5 defines four levels of AN severity: mild, BMI greater than 17 kg/m2; moderate, BMI of 16–16.99 kg/m2; severe, BMI of 15–15.99 kg/m2; and extreme, BMI of less than 15 kg/m2 [61]. Once again, the literature indicates a wide range of BMIs in articles attempting to define severe and enduring AN and/or for participation in studies targeting this group of individuals. The two studies of deep brain stimulation with duration criteria of ≥ 10 years for participation also had BMI requirements falling into the DSM extreme category [51, 52]. Deep brain stimulation involves a high degree of risk, and the authors delineated that only individuals with the most severe cases should be included. Similar to duration of illness, participants included in groups indicated as manifesting a severe and enduring phenotype in case studies, clinical trials and studies, tended to have substantially lower BMIs than required per the inclusion criteria. For example, participants in the Bemer et al. bone mineral density (BMD) study had a mean BMI of 12.60 ± 1.60 kg/m2, which was well below the < 16 kg/m2 criteria [62].

Notably, several studies included a low weight cutoff for participation. For example, in their transcranial magnetic stimulation studies, Dalton et al. [45,46,47,48] required a BMI > 14 kg/m2 for participation. The reason provided in the study protocol for the low weight cutoff was “safety precaution” [63]. The deep brain stimulation studies conducted by Park et al. [64] required that participants be severely underweight but with a low-weight BMI criterion of > 13 kg/m2. Although reasons were not given for the low weight cutoff, they stated that participants needed to have a BMI > 13 kg/m2 for surgery, which is understandable given its invasive nature.

Again, as with duration of illness, the literature suggests that BMI should not be used as the sole determinant of severity in AN. In their editorial on the challenges of defining severe and enduring AN, Hay and Touyz [22] recognized the utility of the DSM-5 BMI severity categories but also noted that for those with unremitting AN for a decade or more, having a BMI above the DSM severe range is still associated with marked morbidity.

Psychological assessment:

All the studies reviewed included an assessment of symptoms such as psychological stress, disordered eating, depression, anxiety, obsessiveness, and quality of life. For example, Wildes et al. [60], used the Research and Development Corporation (RAND) 36-Item Health Survey 1.0 (SF-36) to measure health-related quality of life, and found that these scores better classified AN subgroups than BMI and duration of illness. A score of ≤45 on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) found in the DSM-4, which assesses the severity of mental illness [65], was used by Oudijn et al. [51] for inclusion in their deep brain stimulation studies. A plethora of tools was used in assessing eating disorder pathology, with the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [66] and/or various iterations of the EDE-Q being the most prevalent.

-

3.

Treatment response:

Lack of positive response to prior treatment, variously described as treatment resistance, treatment refractoriness, and failure to respond, was also included in assessing AN severity in several of the articles. The number and type of previous treatments required for inclusion in studies varied. For inclusion in deep brain stimulation studies, Park et al. [67] required a lack of positive response to ≥2 “typical modes” of treatment, as did Oudijn et al. [51]. The participant inclusion criteria used by Dalton et al. [48] for transcranial stimulation studies included the need to have completed at least one “previous course of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence” recommended “specialist psychotherapy or specialist day-patient or inpatient treatment”. The clearest classification criterion for treatment resistance was proposed by Hay and Touyz et al. [68]: “exposure to at least two evidence-based treatments delivered by an appropriate clinician or treatment facility together with a diagnostic assessment and formulation that incorporates an assessment of the person’s eating disorder health literacy with an assessment of the person’s stage of change”, which was referenced in the reviews of treatment options for those with severe enduring AN by Zhu et al. and Wonderlich et al. [20, 69]. In contrast, Smith and Woodside [70] defined treatment resistance as “patients with two or more incomplete inpatient admissions and no complete admissions”. Emphasis was placed on patients failing to complete treatment rather than the treatment failing to help patients, although the authors did note that approximately 10% of patients treated at their inpatient facility were “unable to benefit”. As indicated in Fig. 1, the criterion of two or more treatment attempts was most frequently used.

In summary, the literature indicates that a combination of assessments and criteria, including an illness duration of ≥ 7 years, lack of positive response to at least two previous evidence-based treatments, a BMI meeting the DSM-5 for extreme AN, and an assessment of psychological and/or behavioral severity indicating a significant impact on quality of life, were the most prevalent means of defining the severe and enduring AN phenotype. As the DSM-5 includes clear definitions of severe and extreme BMI (15–15.99 kg/m2 and < 15 kg/m2, respectively), the criteria for severe BMI were also used in assessing the genetics literature in the following section.

Inclusion of participants meeting severe enduring anorexia nervosa-defining criteria in studies of anorexia nervosa genetics

The 78 articles identified as meeting the search criteria defined in the methods section were assessed for whether the following inclusion criteria were used and how they were defined:

-

1.

Duration of illness,

-

2.

Prior treatment history,

-

3.

BMI, and.

-

4.

Severity as measured by one or more clinical, social, or psychological scales.

As mentioned previously, neither the statistical strength of the studies nor the study outcomes were assessed, as the purpose was to determine whether genetic studies included those meeting the severe and enduring phenotype criteria defined in the first aim through assessing prevalence of use in the literature. The studies consisted of Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) as well as analyses of polymorphisms, expression, and gene methylation, including but not limited to the leptin (LEP) and the leptin receptor (LEPR) genes, the fat mass and obesity-associated gene (FTO), and the oxytocin receptor (OXTR) gene [16, 71,72,73]. The gender of the study participants was also recorded where reported (Table 2).

Most of the 78 articles, including those specifically stating that the study was of severe AN, did not include criteria defined in the first aim. Most notably, only one article specifically stated that participants included had at least one prior treatment attempt [50].

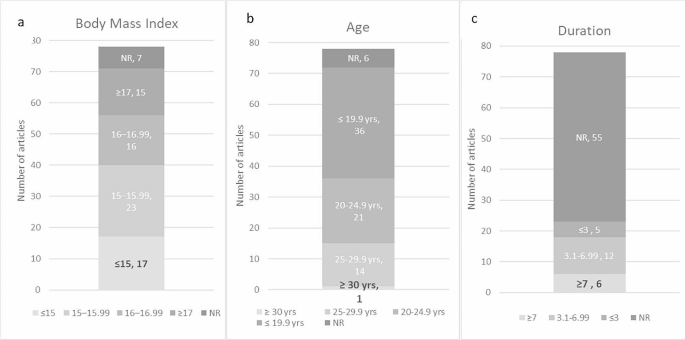

Of the 71 studies reporting mean BMI, the mean BMI for all groups was 15.73 kg/m2 (SD 1.48). For 15 studies (21%), the mean BMI was > 17 kg/m2 (mild DSM-5). Sixteen studies (22%) had a mean BMI of 16–16.99 kg/m2 (moderate DSM-5). Twenty-three studies (32%) had a mean BMI of ≤15.99 kg/m2 (severe DSM-5), and 17 studies (21.8%) included at least one group with a mean BMI of ≤15 kg/m2, required to meet the DSM-5 definition of extreme AN. Only one study included a lifetime minimum BMI of ≤15 kg/m2 as an inclusion criterion [74].

The duration of illness and or minimum duration required for inclusion in studies were reported for 23 (29%) of the 78 articles. Of those 23 studies, 3 (13%) had participants with a mean duration of illness ≤ 3 years, 12 (52%) had a mean of 3.1–6.99 years, and 6 (26%) had a mean of ≥ 7 years. Five of the 23 studies required a duration of illness ≥3 years as a participant inclusion criterion. None of the articles identified required duration of illness ≥7 years as an inclusion criterion.

Assessment of psychological stress, disordered eating, depression, anxiety, obsessiveness, and quality of life was another facet of defining the severity of AN in the studies evaluated. Across the 54 studies identifying defined assessment modalities, 38 different tools, checklists and guidelines were used in various combinations, including the following: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS), Clinical Global Impression anxiety scale (CGI), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory form (STAI); depression: Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS); alexithymia: Toronto Alexithymia Score (TAS); obsessive-compulsive and impulsive symptoms: Young-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms (YBC-EDS), Leyton Obsessional Inventory-Child Version (LOI-CV); Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS); and perfectionism: Child and Adolescent Perfectionism Scale (CAPS). Numerous eating disorder assessment tools, including the Eating Disorders Inventory (EDI), Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q), Eating Attitudes Test (EAT), and the Structured Interview for Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa (SIAB) were also used. Table 3 shows a list of tools and how often they were used.

Historically, the focus of AN research has been on teens and young adults. The current assessment found that, of the 71 studies in which the mean age was reported or could be calculated, the mean of the mean ages reported for study participants was 20.9 (4.26 SD) years. Furthermore, the reported mean age of study participants in 36 (51%) of the 71 studies was ≤19.9 years, 21 (30%) had a mean age of 20-24.9 years, 14 (20%) had a mean age of 25-29.9 years, and only one study had an overall group mean age of ≥ 30 years, although eight studies included individual groups with means ≥ 30 years. Figure 3 provides a summary of the BMI, age and duration findings discussed above.

Number of articles in Table 1 representing the body mass index (BMI), age and duration subgroups indicated. NR = Not reported. A. BMI: 71 of the 78 articles reported BMI (kg/m2), 17 of those 71 had participant mean BMI ≤ 15; Age: 72 of the 78 articles reported age, of those 72, one had a mean participant age over 30 years; Duration: 23 of the 78 articles included duration, of those 23, 6 had participant mean illness duration of ≥ 7 years

Incidence rates for AN are reported to be ten times lower in males, although this is considered an underestimation due to underreporting and underdetection [2]. Only 16 (20%) of the 78 studies included male participants.

Based on the min/max and standard deviations of the mean provided for duration of illness and BMI, it was clear that many of the articles included subsets of individuals meeting the criteria noted herein for severe and enduring AN. However, as data for those specific individuals were often not delineated, it was not possible to determine how the study conclusions may have differed for said subgroups. For example, the mean duration of illness reported by Hernández et al. [75] for the AN restricting type (AN-R) subgroup was 4.03 (4.44 SD) years, indicating that at least some of the participants met the duration criteria.

Nevertheless, there were examples of results being assessed against some measures of severity, including duration. The Booij et al. study [76] AN-R group participant duration of illness was 54.9 (30 SD) months; range: 12–84. They specifically assessed methylation against the cumulative duration of illness and observed associations between duration and methylation levels at 142 probes. The mean duration of illness in the AN-R group in the Steiger et al. study [77] was 96.00 ± 98.91 (12–456) months. They also assessed duration and found an association between chronicity of illness and methylation status at 64 probes mapping to 55 genes.

Other authors evaluated genetic correlation with the severity of various psychological assessments including quality of life, depression, food behaviors, anxiety, and obsessiveness [75, 77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. For example, Acevedo and colleagues found a correlation between specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR), and increased severity of eating disorder symptoms in those with AN [78]. A polymorphism in the promotor region of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), previously associated with stress and depression [91], may impact depression and long-term outcomes in those with AN [79]. Research also suggests a possible correlation between specific haplotypes of the DHEA-producing enzyme cytochrome P450 CYP17A [81] and the C861 allele of the serotonin receptor 1Dβ gene (HTR1B) and severity of anxiety in those with AN.

An example of potential utility in assessing the severe and enduring AN phenotype and the need for larger studies and more funding is the 2022 study by Johansson et al. [50] evaluating polygenic association with AN severity and long-term outcomes. Here, the authors delineated severe and enduring AN criteria, including duration of illness, clinical impairment, BMI, and having undergone at least one previous treatment attempt. They also specified requirements for the AN subtype, thereby narrowing the population. The study, which included 2843 participants followed for up to 16 years (mean: 5.3 years), provided evidence supporting the possible clinical utility of PGSs for assessing eating disorder risk but also noted the need for larger studies and sample sizes to increase statistical power.

In summary, based on the literature reviewed, genetic studies of AN continue to focus largely, but not exclusively, on younger female participants with shorter durations of illness. These findings are not surprising given that the majority of those diagnosed with AN are female, the lack of clearly defined criteria for severe and enduring AN and the need for large numbers of participants to assess significance in genetics research.

Discussion

Attempts to provide criteria for labeling those with severe mental illness as chronic or treatment-resistant need to be executed with care, as has been critically reviewed for illnesses such as schizophrenia and depression [92, 93]. Care should also be taken when defining criteria for severity of AN, which has a higher mortality rate than depression or schizophrenia [94]. However, not defining AN severity more clearly and not focusing on a more severe and enduring phenotype in research may decrease the likelihood of identifying the possible underlying biological etiology of AN. As noted by Wonderlich et al. [20] and responding commentaries by Dalle Grave [95], Wildes [96], and McIntosh [97], a lack of consensus and studies specifically targeting those with severe and enduring AN has resulted in patients being subjected to repetitive employment of largely ineffective treatment strategies resulting in a sense of hopelessness and shame and increasing the risk of suicide [98]. This review of the literature found that a duration of illness ≥7 years and an unsuccessful response to previous evidence-based treatment were the most common inclusion criteria employed, as were various measures of psychological and physical severity.

AN was once thought to be primarily caused by dysfunctional family dynamics and social and cultural pressures [99]. We now have evidence that genetics plays a significant role in its etiology. In recent years, there has been an evidence-based push to reconceptualize AN as a metabopsychiatric disorder [7]. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) continues to provide data on the functioning of the brains of those with AN [100]. The use of large-scale GWAS and genome-wide methylation studies has been gradually revealing the interplay between genetics and environment in AN etiology and persistence, and genetic correlations with other psychiatric disorders [16, 101, 102]. These are all positive advances; however, as evidenced by the individuals included in these studies, female teens and young adults with shorter durations of illness appear to be the primary participants.

Historically, males have been underrepresented in AN research [103]. Until 2013, the DSM listed amenorrhea as a criterion for AN, thereby reinforcing the notion that AN affects only females [61]. According to the literature reviewed, males continue to be underrepresented in AN research.

The challenge of recruiting participants for inclusion in large-scale genetic studies of AN is significant. Of the indicated criteria, the most challenging for researchers to assess is the lack of response to prior evidence-based treatment. Most of the treatments described as evidence-based are not administered according to a defined protocol, making retrospective assessment nearly impossible. Furthermore, those with more severe symptoms of longer duration are often treated in a plethora of settings over many years.

For many of the publications, the data indicate that there were participants meeting the criteria defined in the first aim. However, as these individuals were not assessed as a group, it was not possible to determine whether outcomes for this subset may have differed from those with a less severe presentation. The purpose of the publications that either did not perform these assessments or did not report them in their studies was not to delineate this level of detail, so their absence is understandable. One of the reasons for this may be the small number of individuals meeting the criteria for severe and enduring AN, coupled with the need for a large enough “n” to provide any meaningful statistical assessment, which in turn points back to the need for larger studies and additional funding.

Nevertheless, several studies made concerted efforts to focus on a defined severe and enduring phenotype. For example, Kushima et al. [74] limited their study cohort to those reporting a lifetime lowest BMI < 15 kg/m2, with the median for included participants reported as 11.3 kg/m2, and a mean age of 37.9 years. The authors specifically stated that they focused on the “severe subgroup of patients because patients with severe symptoms or treatment-resistance are more likely to carry rare deleterious variants of large effect”, citing a schizophrenia study [104] as support.

The ultimate goal of AN research is to identify contributing factors to the manifestation and intractability of the disease and, in turn, develop superior evidence-based treatments tailored to the patient. Will next generation sequencing gene panels help in the diagnosis of AN [105]? Kushima et al. [74] suggested that rare copy number variants associated with neurodevelopmental disorders may correlate with more severe eating disorder subtypes. Is it possible to identify those at higher risk of developing severe and enduring illness earlier and in turn treat those patients based on their specific genetic and environmental circumstances instead of employing generic therapy that may work for most patients with eating disorders but is less effective for those in this cohort? Can artificial intelligence be employed to better identify risk in individuals with AN [106]? Will we one day regularly employ genetic testing and pharmacogenetics in treating mental illness, including AN [107, 108]? Several international projects, including ANGI and the Comprehensive Risk Evaluation for Anorexia Nervosa in Twins (CREAT) are attempting to answer these questions and many more [109, 110]. Although these projects do not focus specifically on the severe and enduring phenotype, the availability of in-depth participant health and demographic information paired with genetic analysis should allow for studies of these subsets.

The criteria for evaluating the severity and intractability of AN are evolving, as is the understanding of the disorder. The purpose of a scoping review is to map the literature on an evolving topic and to identify gaps. As such, unlike a systematic review, this review does not attempt to assess the quality of the research conducted, but rather the inclusiveness of study participants. The authors do not attempt to define the severe and enduring phenotype or suggest how the research community should create consensus on the definition. However, by assessing the current literature, we highlight the gaps between the intent to focus on those with severe and enduring AN and the inclusion of this group in published research.

Conclusion and future directions

In conclusion, this review provides an overview of the currently used criteria employed by the research community to define the severity of AN and assesses the last decade of genetics research for the inclusion of study participants meeting these criteria. We found that the following combination of assessments and criteria was used most often in the literature to define AN severity and intractability:

-

1.

Illness duration of ≥ 7 years.

-

2.

lack of positive response to at least two previous evidence-based treatments.

-

3.

A BMI meeting the DSM-5 criteria for extreme AN.

-

4.

An assessment of psychological and/or behavioral severity indicating a significant impact on quality of life.

We also found, especially in recent years, that there has been an attempt to better define severe and enduring AN in hopes of identifying patients, tailoring treatment, and improving outcomes. However, although a small subset of genetic studies reviewed specifically attempted to focus on a severe and enduring phenotype, there was a lack of aligned defining criteria. Furthermore, there is a continued focus on younger females with shorter disease durations.

Those with AN are often stigmatized, and their shame is amplified by the perception that AN is voluntary or even a lifestyle choice [111,112,113]. Those with severe and long-lasting illness are less likely to respond to currently available treatment modalities and have higher levels of mortality [20]. However, they also represent a subgroup of individuals for which genetic findings may be especially helpful [74]. Therefore, it is suggested that future genetics studies make a concerted effort to include older participants, those with longer illness durations, and those whose quality of life is most significantly impacted. It is also critically important that more objective, empirically based techniques, such as biomarker and brain structure and function analysis, be developed to more definitively classify the severe and enduring phenotype, which to this point has primarily been categorized through subjective means [32, 60, 96, 114]. There has been considerable effort in recent years to expand the definition of AN in hopes of being more inclusive and identifying those who may benefit from treatment. However, although expansion has increased the sample size for genetic studies, it could be that focusing on those with longer-lasting and more severe symptomology, even though this is a much smaller group of those with AN, would provide a better chance of identifying the genetic etiology of the disorder. Recent advances have left us far better equipped to make significant progress in developing evidence-based treatments for those with severe and enduring AN. However, these advances require the inclusion of this subgroup in both research and practice.

Limitations

One limitation of the current review is that due to the wide range of similar terminology used to refer to a severe and enduring AN phenotype in the published literature, the searches performed may have left out pertinent articles and viewpoints. Furthermore, although comprehensive for the three electronic databases, the literature search did not include gray literature; thus, information from sources such as dissertations may have been missed.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Kelsey JL. Observational epidemiology. In: Heggenhougen HK, editor. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. Oxford: Academic; 2008. pp. 609–20.

van Eeden AE, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(6):515–24.

van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Review of the burden of eating disorders: mortality, disability, costs, quality of life, and family burden. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2020;33(6):521–7.

Smink FRE, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Epidemiology of eating disorders: incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(4):406–14.

Bemporad JR. Self-starvation through the ages: reflections on the pre-history of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;19(3):217–37.

de Jorge Martínez C, Rukh G, Williams MJ, Gaudio S, Brooks S, Schiöth HB. Genetics of anorexia nervosa: an overview of genome-wide association studies and emerging biological links. J Genet Genomics. 2022;49(1):1–12.

Watson HJ, Yilmaz Z, Thornton LM, Hübel C, Coleman JRI, Gaspar HA, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight risk loci and implicates metabo-psychiatric origins for anorexia nervosa. Nat Genet. 2019;51(8):1207–14.

Lilenfeld LR, Kaye WH, Greeno CG, Merikangas KR, Plotnicov K, Pollice C, et al. A controlled family study of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: psychiatric disorders in first-degree relatives and effects of proband comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(7):603–10.

Holland A, Hall A, Murray R, Russell G, Crisp A. Anorexia nervosa: a study of 34 twin pairs and one set of triplets. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;145(4):414–9.

Holland AJ, Sicotte N, Treasure J. Anorexia nervosa: evidence for a genetic basis. J Psychosom Res. 1988;32(6):561–71.

Klump KL, Miller K, Keel P, McGue M, Iacono W. Genetic and environmental influences on anorexia nervosa syndromes in a population–based twin sample. Psychol Med. 2001;31(4):737–40.

Kortegaard LS, Hoerder K, Joergensen J, Gillberg C, Kyvik KO. A preliminary population-based twin study of self-reported eating disorder. Psychol Med. 2001;31(2):361–5.

Wade TD, Bulik CM, Neale M, Kendler KS. Anorexia nervosa and major depression: shared genetic and environmental risk factors. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(3):469–71.

Walters EE, Kendler KS. Anorexia nervosa and anorexic-like syndromes in a population-based female twin sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1995.

Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Tozzi F, Furberg H, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen NL. Prevalence, heritability, and prospective risk factors for anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(3):305–12.

Yilmaz Z, Hardaway JA, Bulik CM. Genetics and epigenetics of Eating disorders. Adv Genomics Genet. 2015;5:131–50.

Dellava JE, Thornton LM, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen NL, Bulik CM. Impact of broadening definitions of anorexia nervosa on sample characteristics. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(5):691–8.

Eddy KT, Tabri N, Thomas JJ, Murray HB, Keshaviah A, Hastings E, et al. Recovery from anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa at 22-year follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(2):0.

Steinhausen H-C. The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(8):1284–93.

Wonderlich SA, Bulik CM, Schmidt U, Steiger H, Hoek HW. Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: update and observations about the current clinical reality. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(8):1303–12.

Broomfield C, Stedal K, Touyz S, Rhodes P. Labeling and defining severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and critical analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(6):611–23.

Hay P, Touyz S. Classification challenges in the field of eating disorders: can severe and enduring anorexia nervosa be better defined? J Eat Disord. 2018;6:41.

Broomfield C, Stedal K, Touyz S. The Neuropsychological Profile of severe and Enduring Anorexia Nervosa: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2021;12:708536.

Keyes CL, Dhingra SS, Simoes EJ. Change in level of positive mental health as a predictor of future risk of mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2366–71.

Tomczyk S, Schlick S, Gansler T, McLaren T, Muehlan H, Peter LJ, et al. Continuum beliefs of mental illness: a systematic review of measures. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2023;58(1):1–16.

Yang J, Wray NR, Visscher PM. Comparing apples and oranges: equating the power of case-control and quantitative trait association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34(3):254–7.

Strom NI, Grove J, Meier SM, Bækvad-Hansen M, Becker Nissen J, Damm Als T, et al. Polygenic heterogeneity across obsessive-compulsive disorder subgroups defined by a comorbid diagnosis. Front Genet. 2021;12:711624.

Ahangari M, Bustamante D, Kirkpatrick R, Nguyen TH, Verrelli BC, Fanous A, et al. Relationship between polygenic risk scores and symptom dimensions of schizophrenia and schizotypy in multiplex families with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2023;223(1):301–8.

Verduijn J, Milaneschi Y, Peyrot WJ, Hottenga JJ, Abdellaoui A, de Geus EJC, et al. Using clinical characteristics to identify which patients with Major Depressive Disorder have a higher genetic load for Three Psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81(4):316–24.

Antaki D, Guevara J, Maihofer AX, Klein M, Gujral M, Grove J, et al. A phenotypic spectrum of autism is attributable to the combined effects of rare variants, polygenic risk and sex. Nat Genet. 2022;54(9):1284–92.

Wand H, Lambert SA, Tamburro C, Iacocca MA, O’Sullivan JW, Sillari C, et al. Improving reporting standards for polygenic scores in risk prediction studies. Nature. 2021;591(7849):211–9.

Hübel C, Leppä V, Breen G, Bulik CM. Rigor and reproducibility in genetic research on eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51(7):593–607.

Sun B, Li D, Liu W, Zhan S, Pan Y, Zhang X. Surgical treatments for Anorexia Nervosa. In: Sun B, Salles AD, editors. Neurosurgical treatments for Psychiatric disorders. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2015. pp. 175–87.

Broomfield C, Noetel M, Stedal K, Hay P, Touyz S. Establishing consensus for labeling and defining the later stage of anorexia nervosa: a Delphi study. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54(10):1865–74.

Raykos BC, Erceg-Hurn DM, McEvoy PM, Fursland A, Waller G. Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa? Illness severity and duration are unrelated to outcomes from cognitive behaviour therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86(8):702–9.

Ambwani S, Cardi V, Albano G, Cao L, Crosby RD, Macdonald P, et al. A multicenter audit of outpatient care for adult anorexia nervosa: Symptom trajectory, service use, and evidence in support of early stage versus severe and enduring classification. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(8):1337–48.

Fernandes Arroteia I, Husch A, Baniasadi M, Hertel F. Impressive weight gain after deep brain stimulation of nucleus accumbens in treatment-resistant bulimic anorexia nervosa. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(11).

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Duncan L, Yilmaz Z, Gaspar H, Walters R, Goldstein J, Anttila V, et al. Significant locus and metabolic genetic correlations revealed in genome-wide association study of anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(9):850–8.

Robinson P. Severe and enduring eating disorder (SEED): management of Complex presentations of Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa. Wiley; 2009.

Touyz S, Le Grange D, Lacey H, Hay P, Smith R, Maguire S, et al. Treating severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2013;43(12):2501–11.

Calugi S, El Ghoch M, Dalle Grave R. Intensive enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy for severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: a longitudinal outcome study. Behav Res Ther. 2017;89:41–8.

Voderholzer U, Fumi M, Werz J, Körner T, Cuntz U. [3-year course after successful therapy of extreme anorexia nervosa]. Nervenarzt. 2018;89(9):1063–8.

Dalton B, Austin A, Ching BCF, Potterton R, McClelland J, Bartholdy S, et al. My dad was like it’s your brain, what are you doing?‘: participant experiences of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment in severe enduring anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2022;30(3):237–49.

Dalton B, Bartholdy S, McClelland J, Kekic M, Rennalls SJ, Werthmann J, et al. Randomised controlled feasibility trial of real versus sham repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment in adults with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: the TIARA study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e021531.

Dalton B, Foerde K, Bartholdy S, McClelland J, Kekic M, Grycuk L, et al. The effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on food choice-related self-control in patients with severe, enduring anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(8):1326–36.

Dalton B, Lewis YD, Bartholdy S, Kekic M, McClelland J, Campbell IC, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment in severe, enduring anorexia nervosa: an open longer-term follow-up. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2020;28(6):773–81.

Knyahnytska YO, Blumberger DM, Daskalakis ZJ, Zomorrodi R, Kaplan AS. Insula H-coil deep transcranial magnetic stimulation in severe and enduring anorexia nervosa (SE-AN): a pilot study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:2247–56.

Johansson T, Birgegård A, Zhang R, Bergen SE, Landén M, Petersen LV, et al. Polygenic association with severity and long-term outcome in eating disorder cases. Translational Psychiatry. 2022;12(1):61.

Oudijn MS, Mocking RJT, Wijnker RR, Lok A, Schuurman PR, van den Munckhof P, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral anterior limb of the capsula interna in patients with treatment-refractory anorexia nervosa. Brain Stimul. 2021;14(6):1528–30.

Pérez V, Villalba-Martínez G, Elices M, Manero RM, Salgado P, Ginés JM et al. Cognitive and quality‐of‐life related factors of body mass index (BMI) improvement after deep brain stimulation in the subcallosal cingulate and nucleus accumbens in treatment‐refractory chronic anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2022.

Scaife JC, Eraifej J, Green AL, Petric B, Aziz TZ, Park RJ. Deep brain stimulation of the Nucleus accumbens in severe Enduring Anorexia Nervosa: a pilot study. Front Behav Neurosci. 2022;16:842184.

González Macías L, Romo ADJ, Garcia-Anaya M. Group family psychotherapy during relapse. Case report of a novel intervention for severe and enduring anorexia nervosa. Salud Mental. 2021;44:31–7.

Hemmingsen SD, Lichtenstein MB, Hussain AA, Sjögren JM, Støving RK. Case report: cognitive performance in an extreme case of anorexia nervosa with a body mass index of 7.7. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):1–12.

Westermair AL, Perrar KM, Schweiger U. Ein Palliativer Ansatz für schwerste anorexia nervosa? Nervenarzt. 2020;91(5):411–6.

Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Serious and enduring anorexia nervosa from a developmental point of view: how to detect potential risks at an early stage and prevent chronic illness? Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(8):1313–4.

Bianchi A, Stanley K, Sutandar K. The ethical defensibility of Harm Reduction and Eating disorders. Am J Bioeth. 2021;21(7):46–56.

Marzola E, Martini M, Brustolin A, Abbate-Daga G. Inpatients with severe-enduring anorexia nervosa: understanding the enduringness specifier. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64(1):e44.

Wildes JE, Forbush KT, Hagan KE, Marcus MD, Attia E, Gianini LM, et al. Characterizing severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: an empirical approach. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(4):389–97.

American Psychiatric Association APADSMTF. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Bemer P, Di Lodovico L, Haykanush O, Théodon H, Briot K, Carlier R, et al. Bone mineral density at extremely low weight in patients with anorexia nervosa. Clin Endocrinol. 2021;95(3):423–9.

Bartholdy S, McClelland J, Kekic M, O’Daly OG, Campbell IC, Werthmann J, et al. Clinical outcomes and neural correlates of 20 sessions of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in severe and enduring anorexia nervosa (the TIARA study): study protocol for a randomised controlled feasibility trial. Trials. 2015;16(1):1–13.

Park RJ, Scaife JC, Aziz TZ. Study protocol: using deep-brain stimulation, Multimodal Neuroimaging and Neuroethics to understand and treat severe Enduring Anorexia Nervosa. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:24.

Frances A, First MB, Pincus HA. DSM-IV guidebook: American Psychiatric Association; 1995.

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16(4):363–70.

Park RJ, Singh I, Pike AC, Tan JO. Deep brain stimulation in Anorexia Nervosa: hope for the hopeless or Exploitation of the Vulnerable? The Oxford Neuroethics Gold Standard Framework. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:44.

Hay P, Touyz S. Treatment of patients with severe and enduring eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28(6):473–7.

Zhu J, Yang Y, Touyz S, Park R, Hay P. Psychological treatments for people with severe and Enduring Anorexia Nervosa: a Mini Review. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:206.

Smith S, Woodside DB. Characterizing treatment-resistant Anorexia Nervosa. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:542206.

Hübel C, Marzi SJ, Breen G, Bulik CM. Epigenetics in eating disorders: a systematic review. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(6):901–15.

Malcolm A, Phillipou A. Current directions in biomarkers and endophenotypes for anorexia nervosa: a scoping review. J Psychiatr Res. 2021.

Hirtz R, Hinney A. Genetic and epigenetic findings in anorexia nervosa. Med Gen. 2020;32(1):25–9.

Kushima I, Imaeda M, Tanaka S, Kato H, Oya-Ito T, Nakatochi M et al. Contribution of copy number variations to the risk of severe eating disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022.

Hernández S, Camarena B, González L, Caballero A, Flores G, Aguilar A. A family-based association study of the HTR1B gene in eating disorders. Brazilian J Psychiatry. 2016;38:239–42.

Booij L, Casey KF, Antunes JM, Szyf M, Joober R, Israël M, et al. DNA methylation in individuals with anorexia nervosa and in matched normal-eater controls: a genome‐wide study. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(7):874–82.

Steiger H, Booij L, Kahan, McGregor K, Thaler L, Fletcher E, et al. A longitudinal, epigenome-wide study of DNA methylation in anorexia nervosa: results in actively ill, partially weight-restored, long-term remitted and non-eating-disordered women. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2019;44(3):205–13.

Acevedo SF, Valencia C, Lutter M, McAdams CJ. Severity of eating disorder symptoms related to oxytocin receptor polymorphisms in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228(3):641–8.

Castellini G, Ricca V, Lelli L, Bagnoli S, Lucenteforte E, Faravelli C, et al. Association between serotonin transporter gene polymorphism and eating disorders outcome: a 6-year follow‐up study. Am J Med Genet Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genet. 2012;159(5):491–500.

Chen J, Kang Q, Jiang W, Fan J, Zhang M, Yu S, et al. The 5-HTTLPR confers susceptibility to anorexia nervosa in Han Chinese: evidence from a case-control and family-based study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0119378.

Czerniak E, Korostishevsky M, Frisch A, Cohen Y, Amariglio N, Rechavi G, et al. Association between a common CYP17A1 haplotype and anxiety in female anorexia nervosa. Arch Women Ment Health. 2013;16(5):423–8.

Gervasini G, Gordillo I, García-Herráiz A, Flores I, Jiménez M, Monge M, et al. Influence of dopamine polymorphisms on the risk for anorexia nervosa and associated psychopathological features. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(4):551–5.

González LM, García-Herráiz A, Mota-Zamorano S, Flores I, Albuquerque D, Gervasini G. Variability in cannabinoid receptor genes is associated with psychiatric comorbidities in anorexia nervosa. Eating and Weight disorders-studies on Anorexia. Bulimia Obes. 2021;26(8):2597–606.

González LM, García-Herráiz A, Mota-Zamorano S, Flores I, Albuquerque D, Gervasini G. Variants in the obesity-linked FTO gene locus modulates psychopathological features of patients with Anorexia Nervosa. Gene. 2021;783:145572.

Kang Q, Chen J, Yu S, Yuan A, Zhang Y, Zhang R, et al. Association of the 5-HT2A receptor gene promoter polymorphism‐1438G/A with anorexia nervosa and psychopathological traits in the Chinese Han population: a preliminary study. Asia‐Pacific Psychiatry. 2017;9(3):e12284.

Kim Y-R, Kim J-H, Kim MJ, Treasure J. Differential methylation of the oxytocin receptor gene in patients with anorexia nervosa: a pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e88673.

Neyazi A, Buchholz V, Burkert A, Hillemacher T, De Zwaan M, Herzog W, et al. Association of leptin gene DNA methylation with diagnosis and treatment outcome of anorexia nervosa. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:197.

Plana MT, Torres T, Rodríguez N, Boloc D, Gassó P, Moreno E, et al. Genetic variability in the serotoninergic system and age of onset in anorexia nervosa and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2019;271:554–8.

Scott-Van Zeeland AA, Bloss CS, Tewhey R, Bansal V, Torkamani A, Libiger O, et al. Evidence for the role of EPHX2 gene variants in anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(6):724–32.

Yilmaz Z, Kaplan AS, Tiwari AK, Levitan RD, Piran S, Bergen AW, et al. The role of leptin, melanocortin, and neurotrophin system genes on body weight in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;55:77–86.

Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K, Sen S. The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and Depression Meta-analysis Revisited: evidence of genetic moderation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(5):444–54.

Dubreucq J, Plasse J, Franck N. Self-stigma in Serious Mental illness: a systematic review of frequency, correlates, and consequences. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47(5):1261–87.

Gaynes BN, Lux L, Gartlehner G, Asher G, Forman-Hoffman V, Green J, et al. Defining treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(2):134–45.

Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):153–60.

Dalle Grave R. Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: no easy solutions. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(8):1320–1.

Wildes JE. Moving from I know it when I see it to an empirical classification of severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: Commentary on Wonderlich et al. (2020). Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(8):1315–7.

McIntosh VVW. Evidence-based treatments remain the best intervention for good long-term outcome of severe and enduring anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(8):1322–3.

Strober M. Managing the chronic, treatment-resistant patient with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;36(3):245–55.

Dell’Osso L, Abelli M, Carpita B, Pini S, Castellini G, Carmassi C, et al. Historical evolution of the concept of anorexia nervosa and relationships with orthorexia nervosa, autism, and obsessive-compulsive spectrum. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1651–60.

King JA, Bernardoni F, Geisler D, Ritschel F, Doose A, Pauligk S, et al. Intact value-based decision-making during intertemporal choice in women with remitted anorexia nervosa? An fMRI study. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2020;45(2):108–16.

Iranzo-Tatay C, Hervas-Marin D, Rojo-Bofill L, Garcia D, Vaz-Leal F, Calabria I, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling in anorexia nervosa discordant identical twins. Translational Psychiatry. 2022;12(1):1–8.

Lee PH, Anttila V, Won H, Feng Y-CA, Rosenthal J, Zhu Z, et al. Genomic relationships, novel loci, and pleiotropic mechanisms across eight psychiatric disorders. Cell. 2019;179(7):1469–82. e11.

Murray SB, Nagata JM, Griffiths S, Calzo JP, Brown TA, Mitchison D, et al. The enigma of male eating disorders: a critical review and synthesis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;57:1–11.

Zoghbi AW, Dhindsa RS, Goldberg TE, Mehralizade A, Motelow JE, Wang X et al. High-impact rare genetic variants in severe schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021;118(51):e2112560118.

Ceccarini MR, Precone V, Manara E, Paolacci S, Maltese PE, Benfatti V, et al. A next generation sequencing gene panel for use in the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. 2022;27(5):1869–80.

Guo Y, Wei Z, Keating BJ, Hakonarson H. Machine learning derived risk prediction of anorexia nervosa. BMC Med Genomics. 2016;9:4.

Lunenburg CATC, Gasse C. Pharmacogenetics in psychiatric care, a call for uptake of available applications. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113336.

Smith S, Woodside B. Is there a role for pharmacogenetics in the treatment of anorexia nervosa? Pharmacogenomics. 2016;17.

Thornton LM, Munn-Chernoff MA, Baker JH, Juréus A, Parker R, Henders AK, et al. The Anorexia Nervosa Genetics Initiative (ANGI): overview and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;74:61–9.

Seidel M, Ehrlich S, Breithaupt L, Welch E, Wiklund C, Hübel C, et al. Study protocol of comprehensive risk evaluation for anorexia nervosa in twins (CREAT): a study of discordant monozygotic twins with anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):1–18.

Crisafulli MA, Von Holle A, Bulik CM. Attitudes towards anorexia nervosa: the impact of framing on blame and stigma. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41(4):333–9.

Mitchison D, Hay P, Engel S, Crosby R, Le Grange D, Lacey H, et al. Assessment of quality of life in people with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: a comparison of generic and specific instruments. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):1–9.

Conti J, Rhodes P, Adams H. Listening in the dark: why we need stories of people living with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa. J Eat Disorders. 2016;4(1):1–7.

Steinglass JE, Glasofer DR, Dalack M, Attia E. Between wellness, relapse, and remission: stages of illness in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2020;53(7):1088–96.

Calabrese L, Scolnick B, Zupec-Kania B, Beckwith C, Costello K, Frank GKW. Ketogenic diet and ketamine infusion treatment to target chronic persistent eating disorder psychopathology in anorexia nervosa: a pilot study. Eat Weight Disord. 2022;27(8):3751–7.

Forbes DA. Futility in adolescent anorexia nervosa and the question of withdrawal of care. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;56(1):5–7.

Guinhut M, Godart N, Benadjaoud MA, Melchior JC, Hanachi M. Five-year mortality of severely malnourished patients with chronic anorexia nervosa admitted to a medical unit. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;143(2):130–40.

Israely M, Ram A, Brandeis R, Alter Z, Avraham Y, Berry EM. A double Blind, Randomized Cross-over Trial of Tyrosine treatment on cognitive function and psychological parameters in severe hospitalized anorexia nervosa patients. Isr J Psychiatry. 2017;54(3):52–8.

Mishima R, Isobe M, Noda T, Tose K, Kawabata M, Noma S, et al. Structural brain changes in severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: a multimodal magnetic resonance imaging study of gray matter volume, cortical thickness, and white matter integrity. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2021;318:111393.

Russell J, Mulvey B, Bennett H, Donnelly B, Frig E. Harm minimization in severe and enduring anorexia nervosa. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2019;31(4):391–402.

Strand M, Sjöstrand M, Lindblad A. A palliative care approach in psychiatry: clinical implications. BMC Med Ethics. 2020;21(1):29.

Tumba J, Smith M, Rodenbach KE. Clinical and ethical dilemmas in the Involuntary treatment of Anorexia Nervosa. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2023;31(1):14–21.

Ando T, Ishikawa T, Hotta M, Naruo T, Okabe K, Nakahara T, et al. No association of brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism with anorexia nervosa in Japanese. Am J Med Genet Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genet. 2012;159(1):48–52.

Ando T, Tamura N, Mera T, Morita C, Takei M, Nakamoto C, et al. Association of the c. 385C > A (p. Pro129Thr) polymorphism of the fatty acid amide hydrolase gene with anorexia nervosa in the Japanese population. Mol Genet Genom Med. 2014;2(4):313–8.

Augoulea A, Armeni E, Deligeoroglou E, Paschou SA, Papadimitriou G, Stergioti E, et al. MTHFR Polymorphisms in girls with Anorexia Nervosa: implications on Body Weight. Endocr Res. 2021;46(2):80–5.

Baeza-Velasco C, Seneque M, Courtet P, Olié É, Chatenet C, Espinoza P et al. Joint hypermobility and clinical correlates in a group of patients with eating disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12.

Batury V-L, Walton E, Tam F, Wronski M-L, Buchholz V, Frieling H, et al. DNA methylation of ghrelin and leptin receptors in underweight and recovered patients with anorexia nervosa. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;131:271–8.

Boehm I, Walton E, Alexander N, Batury V-L, Seidel M, Geisler D, et al. Peripheral serotonin transporter DNA methylation is linked to increased salience network connectivity in females with anorexia nervosa. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2020;45(3):206–13.

Caso JR, Graell M, Navalon A, MacDowell KS, Gutierrez S, Soto M, et al. Dysfunction of inflammatory pathways in adolescent female patients with anorexia nervosa. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020;96:109727.

Ceccarini MR, Tasegian A, Franzago M, Patria FF, Albi E, Codini M, et al. 5-HT2AR and BDNF gene variants in eating disorders susceptibility. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2020;183(3):155–63.

Chang X, Qu H, Liu Y, Glessner J, Hou C, Wang F, et al. Microduplications at the 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 locus are enriched in patients with anorexia nervosa. J Psychiatr Res. 2019;113:34–8.

Clarke J, Ramoz N, Fladung A-K, Gorwood P. Higher reward value of starvation imagery in anorexia nervosa and association with the Val66Met BDNF polymorphism. Translational Psychiatry. 2016;6(6):e829–e.

Clarke T-K, Crist RC, Doyle GA, Weiss AR, Brandt H, Crawford S, et al. Characterization of genetic variation in the VGLL4 gene in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatr Genet. 2014;24(4):183–4.

Dmitrzak-Weglarz M, Moczko J, Skibinska M, Slopien A, Tyszkiewicz M, Pawlak J, et al. The study of candidate genes related to the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of anorexia nervosa: classical association study versus decision tree. Psychiatry Res. 2013;206(1):117–21.

Dmitrzak-Weglarz M, Szczepankiewicz A, Slopien A, Tyszkiewicz M, Maciukiewicz M, Zaremba D, et al. Association of the glucocorticoid receptor gene polymorphisms and their interaction with stressful life events in Polish adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. Psychiatria Danubina. 2016;28(1):0–57.

Dudzińska E, Szymona K, Kloc R, Kocki T, Gil-Kulik P, Bogucki J, et al. Fractalkine, sICAM-1 and Kynurenine Pathway in Restrictive Anorexia nervosa–exploratory study. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):339.

Ehrlich S, Walton E, Roffman JL, Weiss D, Puls I, Doehler N, et al. Smoking, but not malnutrition, influences promoter-specific DNA methylation of the proopiomelanocortin gene in patients with and without anorexia nervosa. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(3):168–76.

Faje AT, Fazeli PK, Katzman DK, Miller KK, Breggia A, Rosen CJ, et al. Sclerostin levels and bone turnover markers in adolescents with anorexia nervosa and healthy adolescent girls. Bone. 2012;51(3):474–9.

Fan Y, Støving RK, Berreira Ibraim S, Hyötyläinen T, Thirion F, Arora T et al. The gut microbiota contributes to the pathogenesis of anorexia nervosa in humans and mice. Nat Microbiol. 2023.

Favaro A, Clementi M, Manara R, Bosello R, Forzan M, Bruson A, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase genotype modifies executive functioning and prefrontal functional connectivity in women with anorexia nervosa. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2013;38(4):241–8.

Franzago M, Orecchini E, Porreca A, Mondanelli G, Orabona C, Dalla Ragione L et al. SLC6A4 DNA methylation levels and Serum Kynurenine/Tryptophan Ratio in eating disorders: a possible link with psychopathological traits? Nutrients. 2023;15(2).

Galimberti E, Fadda E, Cavallini MC, Martoni RM, Erzegovesi S, Bellodi L. Executive functioning in anorexia nervosa patients and their unaffected relatives. Psychiatry Res. 2013;208(3):238–44.

Gamero-Villarroel C, González LM, Gordillo I, Carrillo JA, García-Herráiz A, Flores I, et al. Impact of NEGR1 genetic variability on psychological traits of patients with eating disorders. Pharmacogenomics J. 2015;15(3):278–83.

Gamero-Villarroel C, González LM, Rodríguez‐López R, Albuquerque D, Carrillo JA, García‐Herráiz A, et al. Influence of TFAP 2B and KCTD 15 genetic variability on personality dimensions in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Brain Behav. 2017;7(9):e00784.

Gamero-Villarroel C, Gordillo I, Carrillo JA, García-Herráiz A, Flores I, Jiménez M, et al. BDNF genetic variability modulates psychopathological symptoms in patients with eating disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(8):669–79.

Gamero-Villarroel C, Rodriguez-Lopez R, Jimenez M, Carrillo JA, Garcia-Herraiz A, Albuquerque D, et al. Melanocortin-4 receptor gene variants are not associated with binge-eating behavior in nonobese patients with eating disorders. Psychiatr Genet. 2015;25(1):35–8.

Gervasini G, González LM, Gamero-Villarroel C, Mota-Zamorano S, Carrillo JA, Flores I, et al. Effect of dopamine receptor D4 (DRD4) haplotypes on general psychopathology in patients with eating disorders. Gene. 2018;654:43–8.

Gervasini G, Gonzalez L, Mota-Zamorano S, Gamero-Villarroel C, Carrillo J, Flores I, et al. Association of COMT Val158Met polymorphism with psychopathological symptoms in patients with eating disorders. Curr Mol Med. 2018;18(1):65–70.

He Q, Lian C, Peng S, Chen H, Kang Q, Chen J. Hypermethylation of the serotonin transporter gene and paternal parenting styles in untreated anorexia nervosa patients: a pilot study. Heliyon. 2023;9(2).

Hernández-Muñoz S, Camarena-Medellin B, González-Macías L, Aguilar-García A, Flores-Flores G, Dominguez DL, et al. Sequence analysis of five exons of SLC6A4 gene in Mexican patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Gene. 2020;748:144675.

İnan-Erdoğan I, Akgül S, Işgın-Atıcı K, Tuğrul-Yücel T, Boduroğlu K, Derman O, et al. Effects of vitamin D and estrogen receptor polymorphisms on bone mineral density in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2019;32(12):1377–84.

Kesselmeier M, Pütter C, Volckmar A-L, Baurecht H, Grallert H, Illig T, et al. High-throughput DNA methylation analysis in anorexia nervosa confirms TNXB hypermethylation. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018;19(3):187–99.

Kim Y, Trace SE, Crowley JJ, Brownley KA, Hamer RM, Pisetsky DS, et al. Assessment of gene expression in peripheral blood using RNAseq before and after weight restoration in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(1):287–93.

Kim YR, Kim JH, Kim CH, Shin JG, Treasure J. Association between the oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism (rs53576) and bulimia nervosa. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2015;23(3):171–8.

Kucharska K, Kot E, Biernacka K, Zimowski J, Rogoza R, Rybakowski F, et al. Interaction between polymorphisms of the oxytocinergic system genes and emotion perception in inpatients with anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2019;27(5):481–94.

Lawson EA, Holsen LM, Santin M, Meenaghan E, Eddy KT, Becker AE, et al. Oxytocin secretion is associated with severity of disordered eating psychopathology and insular cortex hypoactivation in anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metabolism. 2012;97(10):E1898–908.

Lin Z, Lebrun N, Clarke J, Duriez P, Gorwood P, Ramoz N, et al. Identification of rare variants in cadm1 in patients with anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113191.

Lutter M, Bahl E, Hannah C, Hofammann D, Acevedo S, Cui H, et al. Novel and ultra-rare damaging variants in neuropeptide signaling are associated with disordered eating behaviors. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0181556.

Müller TD, Greene BH, Bellodi L, Cavallini MC, Cellini E, Di Bella D, et al. Fat mass and obesity-associated gene (FTO) in eating disorders: evidence for association of the rs9939609 obesity risk allele with bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. Obes Facts. 2012;5(3):408–19.

Zipfel S, Wild B, Groß G, Friederich HC, Teufel M, Schellberg D, et al. Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimised treatment as usual in outpatients with anorexia nervosa (ANTOP study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):127–37.

Ortega FJ, Agüera Z, Sabater M, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Alonso‐Ledesma I, Xifra G, et al. Genetic variations of the bitter taste receptor TAS2R38 are associated with obesity and impact on single immune traits. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2016;60(7):1673–83.

Phillipou A, Gurvich C, Castle DJ, Rossell SL. Anorexia nervosa, weight restoration and biological siblings: differences and similarities in clinical characteristics. Australas Psychiatry. 2022;30(4):458–61.

Rudolph A, Stengel A, Suhs M, Schaper S, Wölk E, Rose M, et al. Circulating neuronatin levels are positively Associated with BMI and body Fat Mass but not with psychological parameters. Nutrients. 2023;15(16):3657.

Sala M, Han K, Acevedo S, Krawczyk DC, McAdams CJ. Oxytocin receptor polymorphism decreases midline neural activations to social stimuli in anorexia nervosa. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2183.

Schroeder M, Eberlein C, de Zwaan M, Kornhuber J, Bleich S, Frieling H. Lower levels of cannabinoid 1 receptor mRNA in female eating disorder patients: association with wrist cutting as impulsive self-injurious behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(12):2032–6.

Shih PB, Yang J, Morisseau C, German JB, Zeeland AA, Armando AM, et al. Dysregulation of soluble epoxide hydrolase and lipidomic profiles in anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(4):537–46.

Shimizu M, Kawai K, Yamashita M, Shoji M, Takakura S, Hata T, et al. Very long chain fatty acids are an important marker of nutritional status in patients with anorexia nervosa: a case control study. Biopsychosoc Med. 2020;14(1):1–9.

Stergioti E, Deligeoroglou E, Economou E, Tsitsika A, Dimopoulos K, Daponte A, et al. Gene receptor polymorphism as a risk factor for BMD deterioration in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(7):716–9.

Subramanian S, Braun PR, Han S, Potash JB. Investigation of differential HDAC4 methylation patterns in eating disorders. Psychiatr Genet. 2018;28(1):12–5.

Svedlund A, Tubic B, Elfvin A, Magnusson P, Swolin-Eide D. The significance of the FTO Gene for Weight and body composition in Swedish women with severe Anorexia Nervosa during Intensive Nutrition Therapy. J Am Nutr Assoc. 2022;41(6):594–9.