Abstract

Background

Preliminary studies suggest that both childhood experiences and coping behaviours may be linked to eating disorder symptoms.

Methods

In this study maladaptive schema coping modes were investigated as mediators in the relationship between perceived negative parenting and disordered eating. A total of 174 adults with eating and/or body image concerns completed questionnaires measuring parenting experiences, schema modes, and disordered eating behaviours.

Results

Perfectionistic Overcontroller, Self-Aggrandiser, Compliant Surrenderer, Detached Protector and Detached Self-Soother coping modes partially explained the variance in the relationships between perceived negative parenting experiences and the behaviours of restricting and compensation (purging and overexercising).

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that Overcompensatory, Avoidant and Surrender coping mechanisms all appear to play a role in the maintenance of eating disorder symptoms, and that there are multiple complex relationships between these and Early Maladaptive Schemas that warrant further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Plain english summary

In this study, we investigated whether perceived childhood parenting experiences and coping mechanisms played a role in the development of eating disorder symptoms in a group of 174 participants who indicated that they had difficulties with eating and/or body image. The maladaptive coping mechanisms of perfectionism, avoidance, and compliance partially explained the relationship between perceived negative parenting experiences and restriction/purging/overexercising. Schema Therapy may therefore be an appropriate treatment that can address developmental factors associated with parenting, alongside here-and-now maintaining factors, including core beliefs and coping style.

Background

Eating disorders are considered one of the most difficult psychopathologies to treat, due to high levels of complexity, ego-syntonicity, chronicity, and heterogeneity [1, 48]. Comorbidity with other mental health disorders is high, including anxiety, mood and substance misuse disorders [5, 11, 34] and personality disorders [8]. Although Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is the treatment of choice for eating disorders (EDs), a significant number of sufferers do not respond [2]. Anorexia Nervosa in particular remains exceptionally difficult to treat, with Enhanced CBT outcome trials reporting low remission and high attrition rates [9, 10, 18, 19]. Given the limited efficacy of maintenance models such as CBT in the treatment of EDs, especially for those with higher comorbidity and severity, deeper level factors are now a focus of the ED literature [22], and there is a need for new and innovative therapeutic models to improve our conceptualization and treatment of the eating disorders [13, 55].

Schema Therapy encapsulates developmental, maintenance, and deeper level themes and was developed to conceptualise complex psychopathology with high comorbidity, including personality disorders [57]. Early maladaptive schemas (EMS) are defined as unconditional, implicit, and irrefutable cognitive beliefs that result from unmet core needs and repeated negative experiences with significant others during childhood and adolescence [57]. EMS act as frameworks for understanding interpersonal relationships and life experiences [28]. Schema modes are defined as the states or parts of the personality and coping mechanisms that manifest moment-to-moment. Further, there is preliminary, though limited, empirical support for the application of the schema model to ED populations [29, 40, 41]. Specifically, research has linked EMS and schema processes to ED pathology, and ED populations have been found to score higher on EMS [22, 25, 52] and schema modes [45, 49] than non-clinical populations. Preliminary studies suggest that the Compliant Surrenderer, and two avoidant coping modes, Detached Self-Soother and Detached Protector, appear to be higher in the ED population than in non-clinical populations [45] and other clinical groups [49].

Preliminary studies have also reported a link between negative parenting experiences – particularly emotional abuse and invalidation – and ED pathology [17, 24, 25, 47, 53]. Further, emerging evidence suggests EMS and schema coping processes may explain the link between adverse childhood experiences and the onset of ED pathology [15, 36, 47]. Turner et al. [47] found high maternal over-protection and low paternal care were significantly related to the ‘Defectiveness’ and ‘Dependence’ schemas. In turn, Defectiveness and Dependence mediated the relationship between parental bonding and ED symptoms. Similarly, Deas et al. [15] found participants with AN had significantly more EMS – particularly perfectionistic schemas - and perceived their parents as less caring and more controlling than healthy controls. Sheffield et al. [36] also found the variables of social control (an over-compensation process) and behavioural-somatic avoidance (an avoidance process) to partially mediate correlations between particular negative parenting experiences and ED pathology. This is the first study to our knowledge that has explored the role of dysfunctional coping modes in explaining the relationship between parenting and ED behaviours.

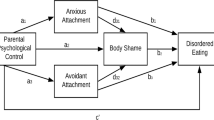

The current study aimed to extend the literature by investigating whether dysfunctional coping modes mediate the relationship between perceived negative parenting and the ED behaviours of restricting, binging, and overcompensation (purging and overexercising). Schema coping modes were selected as a key variable since they amalgamate EMS and schema processes into a unified construct, both of which have been empirically linked to ED pathology [22, 25, 27]. The three overarching coping mechanisms that encompass the coping modes are ‘Surrender’ (Compliant Surrenderer mode), ‘Overcompensation’ (Perfectionistic Overcontroller mode, Self Aggrandiser Mode, Bully and Attack Mode), and ‘Avoidance’ (Detached Protector, Detached Self-Soother). Based on the aforementioned preliminary research, it is hypothesized that perceived negative parenting experiences will be positively correlated with both ED behaviours and dysfunctional coping modes, with behaviours and coping modes also positively correlated. It is further hypothesized that dysfunctional coping modes will mediate the relationship between (a) perceived negative parenting and (b) ED behaviours.

Method

Participants

Given the high prevalence of ED behaviours (full and subthreshold) within the general population [20] the current study recruited participants through advertisements on ED and psychology pages and groups on LinkedIn and Facebook, requesting individuals aged 18 to 65 who held concerns about their eating behaviours, eating attitudes, and/or body image to take part in an online survey exploring how perceptions of parenting may impact the development of specific coping modes which may in turn influence eating and body image. The advertisement included a link to the survey which participants were invited to complete online through Survey Monkey. In all, 187 participants completed the study questionnaire. Thirteen participants were excluded as they failed to meet the key selection criteria of eating and/or body image concerns, as measured by the Eating disorder diagnostic scale (EDDS; [44]).

The final sample included 174 participants ranging in age from 18 to 65 years (m = 28.6, SD = 9.2). Participant demographics, including diagnoses of EDs, are presented in Table 1. Diagnoses were made using self-report responses on the EDDS following the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5; [3]) criteria. However, eating disorder behaviours rather than diagnoses were used as outcome variables. 129 participants met the criteria for an Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED), with 14.4 % (25) of these reporting a BMI of 18.5 or less. Along with the fact that none of the sample met criteria for full threshold Bulimia or Binge Eating Disorder, it appears that a high proportion of the sample were engaging in significant food restriction, with binge eating being underrepresented.

Instruments

Young Parenting Inventory-Revised (YPI-R; [37])

The YPI-R assesses perceived negative parenting. The YPI-R is a 37-item questionnaire measuring perceived parenting styles, namely: emotionally depriving; overprotective; belittling; perfectionist; pessimistic/fearful; controlling; emotionally inhibited; punitive; and conditional/narcissistic. Items relating to each style were rated using two 6-point Likert scales – one for perceptions of the mother and one for the father. Scores for each style were determined by summing the answers of items associated with each style, with higher scores indicating greater perceptions of that parenting style occurring. The YPI-R has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of perceived parenting [37].

Schema Mode Inventory (SMI, [56])

The SMI is a 124-item self- report measure assessing: child modes (vulnerable and emotional states), dysfunctional coping modes (Compliant Surrenderer, Detached Self-Soother, Detached Protector, Self-aggrandizer, and Bully/attack), parent modes (the Punitive and Demanding modes), and adaptive modes (the Healthy Adult). In this study only the dysfunctional coping modes were explored. In addition, eleven items were added to the SMI to measure the Perfectionistic Overcontroller coping mode. These items had been removed from the original SMI after analyses showed it did not emerge as a separate factor. However, as original analyses were not conducted specifically with an ED population, it was considered prudent to re-include it in this study due to the clinical observation that perfectionism is typical in this population [15, 39, 50, 51]. Participants rated how frequently each statement applied to them on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from “never or almost never” to “all of the time”. Scores for each dysfunctional coping mode were calculated using the mean score of all items related to that mode. Lobbestael et al. [26]) indicated good internal consistencies (Cronbach’s α ranging from .76 to .96), and test-retest validity (mean ICC =. 84).

Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (EDDS; [44])

The EDDS is a 22-item self-report measure of full and sub-threshold Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and Binge Eating Disorders. Research evidence shows the EDDS has high internal consistency (α = .89) and test-retest reliability (0.87) and is a valid measure when used with both adolescents and adults [43, 44]. In addition, subscales on the Eating Disorder Examination [12] correlate moderately with total EDDS scores, and concordance between diagnoses made by these methods is high, ranging from 93 % for Binge Eating Disorder to 99 % for Anorexia Nervosa [44]. Participants were asked to estimate over the past 3 months how often each week on average they had engaged in binge-eating, excessive exercise, vomiting, fasting and used laxatives or diuretics (range: 0–14). As the current study used a general population sample, ED behaviours (restriction, binge-eating, compensatory behaviours (over-exercise, purging), rather than diagnoses, were used as outcome variables.

Procedure

Design

The study used a quantitative, cross-sectional survey design.

Statistical power

As the Schema Mode Inventory (SMI) has not been validated for use with ED populations, statistical power was estimated from previous studies using the SMI with personality disorder samples that reported moderate effects (d = 0.56: [33]). Given a medium effect size, power of .80, and an alpha level of .05, G*Power [16] software calculated a minimum of 129 participants were required for the study.

Ethical considerations

The University of South Australia’s Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlational analyses were conducted using the Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21. Bootstrap mediation methods outlined by Preacher and Hayes [31] were used to analyse the mediating role of dysfunctional coping modes in the relationship between perceived negative parenting experiences and disordered eating. This involved calculating the direct effect (c) of perceived negative parenting experiences (a) on disordered eating (b), followed by calculating the total effect (c’) of that same relationship, modelling in the mediator variable, and finally calculating the indirect effect (a x b) of the relationship through the mediator variable (dysfunctional coping mode). The mediation classification decision tree developed by Zhao et al. [58] was used to determine the type of mediation and the theoretical implications. Five thousand bootstrap re-samples using the bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap method were applied to all indirect effect analyses, which were conducted using the AMOS Graphics Software [4], Version 20. This method affords a number of benefits when compared to the Sobel test, including increased statistical power, the ability to detect indirect effects when direct effects are not detected, and the ability to conduct significance tests on the indirect effect without the need for normally distributed variables [58]. Complementary mediation is synonymous with partial mediation [58].

Results

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics including the mean and standard deviations for each variable and internal consistency analysis are included in Table 2.

Correlational analyses

Pearson correlational analyses between perceived negative parenting experiences, specific coping modes, and disordered eating are presented in Table 3. Both restricting and compensatory behaviour were weakly correlated with a variety of different perceived negative parenting experiences, however binge eating was not correlated at all and was thus excluded from the mediation analysis. All dysfunctional coping styles, with the exception of Bully/attack, were weakly to moderately correlated with several different parenting experiences, with the strongest correlations seen between the Perfectionistic Overcontroller and both controlling and conditional/narcissistic father, Detached Self-soother with belittling, emotionally depriving and emotionally inhibited mother, and both the Compliant Surrenderer and Detached Protector with emotionally inhibited mother. Restriction was weakly to moderately correlated with all dysfunctional coping modes except Bully/attack, with the strongest correlation being with Perfectionistic Overcontroller. Binge eating was only weakly correlated with a single mode – the Detached Protector. Finally, compensatory behaviour was strongly correlated with the Detached Protector, with weak to moderate correlations with all other dysfunctional coping modes.

Model and mediation analyses

In the first instance a model was run to assess the percentage of variance explained in disordered eating by the schema modes in the present study. Together the six schema modes explained 18 % of the variance in restricting, 23 % of the variance in binging and 23 % of the variance in purging/overexercising.

All significant correlations between perceived negative parenting variables and ED behaviours were investigated to determine whether dysfunctional coping modes mediated the relationships. Given the large number of correlations performed a more stringent significance level (p < .01) was set to determine inclusion of specific perceived negative parenting styles in the mediation analyses. As Table 4 shows, the relationships between perceived negative parenting experiences and restricting were mediated by both the Perfectionistic Overcontroller and Self-Aggrandiser, with the former fully mediating four relationships between perceived parenting styles and restricting. The Perfectionistic Overcontroller and Self-Aggrandiser also mediated the relationships between perceived negative parenting and compensatory behaviour, although the Self-Aggrandiser explained very little variance. The coping mode of Bully/attack was not correlated with any perceived negative parenting variables and was thus excluded from mediational analysis. The Compliant Surrenderer was found to mediate the relationships between negative parenting and both restricting and compensatory behaviour. The Detached Protector and Detached Self-Soother further mediated the relationships between perceived negative parenting experiences and both restriction and compensatory behaviour.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to explore the relationship between parenting, dysfunctional coping modes, and ED behaviours. Findings from this study highlight the role of the dysfunctional coping modes Perfectionistic Overcontroller, Self-Aggrandiser, Compliant Surrenderer, Detached Self-Soother and Detached Protector which partially explained the variance in the relationship between perceived negative parenting experiences and both restriction and compensatory behaviours in this sample. These findings build on previous research highlighting the potentially important relationship between coping processes and eating disordered behaviours [36, 45], and suggest that negative parenting behaviours that interfere with meeting the core emotional needs of childhood may not only be associated with the development of EMS but may also influence eating behaviours via the coping modes that the individual adopts.

The association between coping modes and both restricting and compensatory behaviour suggests that disordered eating is likely to fulfil a range of functions. Previous studies have suggested that eating disorder behaviours may function either as primary or secondary avoidance strategies, whereby individuals restrict, purge or overexercise in a compulsive or ritualised manner [7, 14, 21, 46] either as a means to reduce the chances of schema activation, or as a secondary strategy to block emotional distress that results from bingeing or other dietary transgressions [38, 39, 54]. Within the context of the Detached Protector/Self-Soother modes, restrictive and compensatory eating behaviours can function as a form of primary or secondary emotional avoidance whilst generating soothing feelings of numbness, or in some cases euphoria [23, 42]. In contrast, in Compliant Surrenderer mode, eating disordered behaviours may function as a form of passive compliance in deference to negative self-beliefs (associated with EMS) and the ED ‘voice’, thereby surrendering control to the disorder [32, 35].

Further, this study highlights the potential importance of the Perfectionistic Overcontroller mode, whereby via a focus on controllable behavior (i.e. restrictive eating rituals and perfectionism) the individual may overcompensate for underlying vulnerability and shame by replacing it with predictability, certainty, and a pseudo-sense of competence/self-worth [39, 53]. This supports previous research asserting the overcompensatory role of eating disordered behaviours (e.g. [6, 30]). Although the Self-Aggrandiser mode also functions as a form of overcompensation, this mode was endorsed at a relatively low level and only weakly correlated with eating behaviours, consistent with previous findings [45, 49].

Binge-eating was not found to correlate with perceived negative parenting, although this finding is likely to be a function of the lack of Bulimia Nervosa/binge eating in this sample.

These findings support previous theory suggesting the need to consider developmental factors and the function of ED behaviours in conjunction with maintenance factors, when conceptualising and treating EDs [36, 39, 45, 54]. The study also emphasises that treatment of EDs cannot rely solely on trait-based factors (i.e. EMS), and intervening with and understanding state factors (i.e. coping modes) should inform the conceptualisation of eating disorder symptoms. A major aspect of the Schema Mode Model is to challenge unhelpful messages that may be derived from early experiences and to build ‘Healthy Adult’ coping through a range of cognitive, behavioural, interpersonal and experiential techniques. Those with eating disorders are helped to recognise [previously unacknowledged] emotional needs, and to internalise a sense of self-compassion that enables them to begin to seek healthy relationships and interpersonal patterns, which thereby enables them to get these needs met. This is accomplished through a range of methods, including limited reparenting techniques, imagery rescripting, chair-work, and empathic confrontation [39].

Future studies in this area should extend the focus on schema modes to investigate the relationship between parenting, eating disorder behaviours and other types of modes (i.e. Parent and Child modes). Future studies should also explore the role of other negative experiences from childhood, including bullying, in the development of EMS, schema modes, and ED behaviours.

Methodological considerations and limitations

A limitation of the current study is the fact that each of the behaviours (restriction, binging, purging and overexercising) were only measured with a single question, which may not adequately capture the complexity of these behaviours. In order to minimise participant fatigue, only the coping mode subscales of the SMI were included in this study. Moreover, the current study also re-included the Perfectionistic Overcontroller coping mode, despite it being excluded from the original SMI. Both of these issues may affect the reliability of the results. However, the fact that this emerged as an important mode in this study provides further support for future research to use the recently designed specialised SMI for EDs (SMI-ED), which has been validated with this population (Simpson S, Pietrabissa G, Rossi A, Frahn T, Manzoni M, Munro C, Nesci J, Castelnuovo G. Factorial Structure of the Schema Mode Inventory for Eating Disorders in a Clinical Sample, in preparation). Further, all data was gathered via self-report, which is subject to bias. While the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow for causal attributions to be made, and perceptions of parenting styles are subjective, the current study nevertheless provides evidence that dysfunctional coping modes play a key role in the relationship between perceived negative parenting and ED psychopathology.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that Overcompensatory, Avoidant and Surrender coping mechanisms all appear to play a role in the maintenance of eating disorder symptoms, and that there are multiple complex relationships between these and EMS that warrant further investigation. This highlights the importance of early experiences and the potential role of early interventions for younger clients and their families as key to circumvent the development of EMS and dysfunctional coping modes that may lead to ED symptom development. The multitude of significant pathways between particular parenting styles, coping modes and restricting, bingeing and compensatory behaviour also highlight the complexity of ED psychopathology, including the way in which ED behaviours can fulfil multiple functions. This underlines the need to move beyond one-size-fits-all treatment approaches to more individualised approaches that can identify and work with the [historical] functional aspect of ED behaviours linked to coping modes, whilst highlighting their self-sabotaging role in the present. Schema Therapy facilitates the development of more effective and adaptive coping behaviours that directly focus on meeting emotional needs, whilst reducing reliance on ED coping behaviours. Future research that replicates the current findings, as well as research into the efficacy of schema-mode therapy for treating ED behaviours, is now warranted.

References

Abbate-Daga G, Amianto F, Delsedime N, De-Bacco C, Fassino S. Resistance to treatment in eating disorders: A critical challenge. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:294. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-294.

Agras WS, Walsh BT, Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, Kraemer HC. A multicenter comparison of cognitive-behavioural therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:459–66. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.459.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2013

Arbuckle JL. Amos (Version 20.0) [Computer Program]. Chicago: IBM SPSS; 2011.

Blinder BJ, Cumella EJ, Santhara VA. Psychiatric comorbidities of female inpatients with eating disorders. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:454–62. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000221254.77675.f5.

Boone L, Braet C, Vandereycken W, Claes L. Are maladaptive schema domains and perfectionism related to body image concerns in eating disorder patients? Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2012;21(1):45–51. doi:10.1002/erv.2175.

Brewerton TD, Stellefson EJ, Hibbs N, Hodges EL, Cochrane CE. Comparison of eating disorder patients with and without compulsive exercising. Int J Eat Disord. 1995;17(4):413–6. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199505)17:43.0.CO;2-0.

Bruce K, Steiger H. Treatment implications of Axis-II comorbidity in eating disorders. Eat Disord. 2005;13:93–108. doi:10.1080/10640260590893700.

Bulik C, Berkman N, Brownley K, Sedway J, Lohr K. Anorexia nervosa treatment: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:310–20. doi:10.1002/eat.20367.

Byrne SM, Fursland A, Allen KL, Watson H. The effectiveness of enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders: An open trial. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:219–26. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.01.006.

Chen EY, McCloskey MS, Michelson S, Gordon KH, Coccaro E. Characterizing eating disorders in a personality disorders sample. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185:736–43. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.002.

Cooper Z, Fairburn CG. The eating disorder examination: A semistructured interview for the assessment of the specific psychopathology of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 1987;6:1–8. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198701)6:13.0.CO;2-9.

Cooper M, Kelland H. Medication and psychotherapy in eating disorders: Is there a gap between research and practice? J Eat Disord. 2015;3:45–52. doi:10.1186/s40337-015-0080-0.

Davis C, Katzman DK, Kaptein S, Kirsh C, Brewer H, Kalmbach K, Olmstead MP, Woodside DB, Kaplan AS. The prevalence of high-level exercise in the eating disorders: Etiological implications. Compr Psychiatry. 1997;38:321–6. doi:10.1016/S0010-440X(97)90927-5.

Deas S, Power K, Collin P, Yellowlees A, Grierson D. The relationship between disordered eating, perceived parenting, and perfectionistic schemas. Cogn Ther Res. 2011;35:414–24. doi:10.1007/s10608-010-9319-x.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91. doi:10.3758/BF03193146.

Ford G, Waller G, Mountford V. Invalidating childhood environments and core beliefs in women with eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2011;19(4):316–21. doi:10.1002/erv.1053.

Halmi KA, Agras WS, Crow S, Mitchell J, Wilson GT, Bryson SW, Kraemer HC. Predictors of treatment acceptance and completion in anorexia nervosa: Implications for future study designs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:776–81. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.7.776.

Hay P. A systematic review of evidence for psychological treatments in eating disorders: 2005–2012. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:462–9. doi:10.1002/eat.22103.

Hay PJ, Mond J, Buttner P, Darby A. Eating Disorder Behaviors Are Increasing: Findings from Two Sequential Community Surveys in South Australia. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(2):e1541. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001541.

Hechler T, Beumont P, Marks P, Touyz S. How do clinical specialists understand the roles of physical activity in eating disorders? Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2005;13:125–32. doi:10.1002/erv.630.

Jones C, Leung N, Harris G. Dysfunctional core beliefs in eating disorders: A review. J Cogn Psychother: An International Quarterly. 2007;21:156–71. doi:10.1891/088983907780851531.

Kaye WH, Wierenga CE, Bailer UF, Simmons AN, Bischoff-Grethe A. Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels: The neurobiology of Anorexia Nervosa. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:110–20. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2013.01.003.

Kent A, Waller G, Dagnan D. A greater role of emotional than physical or sexual abuse in predicting disordered eating attitudes: The role of mediating variables. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25:159–67. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199903)25:23.0.CO;2-F.

Leung N, Waller G, Thomas G. Core beliefs in anorexic and bulimic women. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(12):736–41. doi:10.1097/00005053-199912000-00005.

Lobbestael J, van Vreeswijk MF, Spinhoven P, Schouten E, Arntz A. The reliability and validity of the Short Schema Mode Inventory (SMI). Behav Cogn Psychother. 2010;38:437–58. doi:10.1017/S1352465810000226.

Luck A, Waller G, Meyer C, Ussher M, Lacey H. The role of schema processes in the eating disorders. Cogn Ther Res. 2005;6:717–32. doi:10.1007/s10608-005-9635-8.

McGinn KL, Young JE. Schema- Focused Therapy. In: Salkovskis PM, editor. Frontiers of Cognitive Therapy. London: Guilford Press; 1996.

McIntosh V, Jordan J, Carter J, Frampton C, McKenzie J, Latner J, Joyce P. Psychotherapy for transdiagnostic binge eating: A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy, appetite-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy, and schema therapy. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:412–20. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.080.

Mountford V, Waller G, Watson D, Scragg P. An experimental analysis of the role of schema compensation in anorexia nervosa. Eat Behav. 2004;5:223–30. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.01.012.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–91. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879.

Pugh M, Waller G. The anorexic voice and severity of eating pathology in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2016;49(6):622–5. doi:10.1002/eat.22499.

Renner F, van Goor M, Arntz A, Butz B, Bernstein D. Short-term group schema therapy for young adults with personality disorders and personality features: Associations with changes in symptomatic distress, schemas, schema modes and coping styles. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51:487–92. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.011.

Rosenvinge JH, Martinussen M, Ostensen E. The comorbidity of eating disorders and personality disorders: A meta-analytic review of studies published between 1983 and 1998. Eat Weight Disord. 2000;5:52–61. doi:10.1007/BF03327480.

Scott N, Hanstock T, Thornton C. Dysfunctional self-talk associated with eating disorder severity and symptomatology. J Eat Disord. 2014;2:14-14. doi:10.1186/2050-2974-2-14.

Sheffield A, Waller G, Emanuelli F, Murray J, Meyer C. Do schema processes mediate links between parenting and eating pathology? Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2009;17:290–300. doi:10.1002/erv.922.

Sheffield A, Waller G, Emanuelli F, Murray J, Meyer C. Links between parenting and core beliefs: Preliminary psychometric validation of the Young Parenting Inventory. Cogn Ther Res. 2005;29:787–802. doi:10.1007/s10608-005-4291-6.

Simpson SG. Kapitel (chapter) 7: Schemamodi bei Essstörungen (A Conceptualisation of Schema Modes in the Eating Disorders). In: Archonti C, Roediger E, de Zwaan M, editors. Schematherapie bei Essstörungen. Weinheim: Beltz; 2016. p. 70–82.

Simpson SG. Schema therapy for eating disorders: A case illustration of the mode approach. In: van Vreeswijk M, Broersen J, Nadort M, editors. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Schema Therapy: Theory, Research, and Practice. 1st ed. UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012. p. 145–71.

Simpson SG, Morrow E, van Vreeswijk M, Reid C. Group schema therapy for eating disorders: A pilot study. Front Psychol. 2010;1:1–10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00182.

Simpson SG, Slowey L. Video therapy for atypical eating disorder and obesity: A case study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2011;7:38–43. doi:10.2174/1745017901107010038.

Spranger SC, Waller G, Bryant-Waugh R. Schema avoidance in bulimic and non-eating disordered women. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;29:302–6. doi:10.1002/eat.1022.

Stice E, Fisher M, Martinez EE. Eating disorder diagnostic scale: Additional evidence of reliability and validity. Psychol Assess. 2004;16(1):60–71. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.60.

Stice E, Telch CF, Rizvi SL. Development and validation of the eating disorder diagnostic Scale: A brief self-report measure of anorexia, bulimia and binge eating disorder. Psychol Assess. 2000;12:123–31. doi:10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.123.

Talbot D, Smith E, Tomkins A, Brockman R, Simpson S. Schema modes in eating disorders compared to a community sample. J Eat Disord. 2015;3:41–4. doi:10.1186/s40337-015-0082-y.

Thien V, Thomas A, Markin D, Birmingham CL. Pilot study of a graded exercise program for the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28:101–6. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(200007)28:1<101::AID-EAT12>3.0.CO;2-V.

Turner HM, Rose KS, Cooper MJ. Parental bonding and eating disorder symptoms in adolescents. The mediating role of core beliefs. Eat Behav. 2005;6:113–8. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.08.010.

Vitousek K, Manke F. Personality variables and disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103(1):137–47. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.103.1.137.

Volderholzer U, Schwartz C, Thiel N, Kuelz AK, Hartmann A, Scheidt CE, Schlegl S, Zeeck A. A comparison of schemas, schema modes and childhood traumas in obsessive-compulsive disorder, chronic pain disorder and eating disorders. Psychopathology. 2014;47:24–31. doi:10.1159/000348484.

Wade TD, Tiggemann M. The role of perfectionism in body dissatisfaction. J Eat Disord. 2013;1:2–8. doi:10.1186/2050-2974-1-2.

Wade TD, Wilksch SM, Paxton SJ, Byrne SM, Austin SB. How perfectionism and ineffectiveness influence growth of eating disorder risk in young adolescent girls. Behav Res Ther. 2015;66:56–63. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2015.01.007.

Waller G. Schema level cognitions in patients with binge eating disorder: A case control study. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;33:458–64. doi:10.1002/eat.10161.

Waller G, Corstorphine E, Mountford E. The role of emotional abuse in the eating disorders: Implications for treatment. Eat Disord. 2007;15(4):317–31. doi:10.1080/10640260701454337.

Waller G, Kennerley H, Ohanian V. Schema-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders. In: Riso LP, du Toit PL, Stein DJ, Young JE, editors. Cognitive schemas and core beliefs in psychological problems: A scientist-practitioner guide. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. p. 139–75.

Wilson G, Grilo C, Vitousek K. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. Am Psychol. 2007;62(3):199–216. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199.

Young JE, Arntz A, Atkinson T, Lobbestael J, Weishaar ME, van Vreeswijk MF, Klokman J. The Schema Mode Inventory. New York: Schema Therapy Institute; 2007.

Young JE, Klosko JS, Weishaar MJ. Schema Therapy: A Practitioner’s Guide. New York: Guildford Press; 2003.

Zhao X, Lynch JG, Chen Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J Consum Res. 2010;37(2):197–206. doi:10.1086/651257.

Acknowledgements

Goran Medos contributed to the final formatting of this manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Susan Simpson, University of South Australia upon reasonable request and with permission of University of South Australia ethics committee.

Authors’ contributions

JB prepared the final manuscript and performed statistical analyses, SSelth led in the design and coordination of the study and drafted the first version of the manuscript. SSimpson conceived the study in collaboration with SSelth, supervised the coordination of the study and co-authored the final manuscript. AS performed statistical analyses and prepared the results section of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed assent/consent to participate was obtained from all participants, and all protocols were approved by The University of South Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC number) 0000031258.

Author note

This manuscript has not been published elsewhere, has not been simultaneously submitted for publication elsewhere, and to the best of our knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, J.M., Selth, S., Stretton, A. et al. Do dysfunctional coping modes mediate the relationship between perceived parenting style and disordered eating behaviours?. J Eat Disord 4, 27 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-016-0123-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-016-0123-1