Abstract

Diarrhea is a common enteric disease in piglets that leads to high mortality and economic losses in swine production worldwide. Antibiotics are commonly used to prevent or treat diarrhea in piglets. However, irrational antibiotic use contributes to the development of resistance in bacteria and antibiotic residues in animal products, threatening public health, while causing gut microbiota dysbiosis and antibiotic-resistant bacterial infection in piglets. Therefore, the quest for alternative products (such as probiotics, prebiotics, organic acids, enzymes, essential oils, medium-chain fatty acids, zinc, and plant extracts) has recently been clearly emphasized through the increase in regulations regarding antibiotic use in livestock production. These antibiotic alternatives could lower the risk of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and meet consumer demand for antibiotic-free food. Several antibiotic alternatives have been proposed, including immunomodulatory probiotics, as candidates to reduce the need for antimicrobial therapy. Many studies have revealed that probiotics can avert and cure bacterial diarrhea by regulating the gut function and immune system of piglets. In this review, we focus on the major pathogenic bacteria causing piglet diarrhea, the research status of using probiotics to prevent and treat diarrhea, their possible mechanisms, and the safety issues related to the use of probiotics. Supplementation with probiotics is a possible alternative to antibiotics for the prevention or treatment of bacterial diarrhea in piglets. Furthermore, probiotics exert beneficial effects on feed efficiency and growth performance of piglets. Therefore, appropriate selection and strategies for the use of probiotics may have a positive effect on growth performance and also reduce diarrhea in piglets. This review provides useful information on probiotics for researchers, pig nutritionists, and the additive industry to support their use against bacterial diarrhea in piglets.

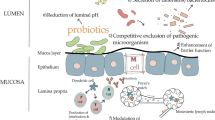

Graphical Abstract

Interaction of probiotics with the gut associated immune system. TLRS, Toll-like receptors; MAPK, Mitogen-activated protein kinases; TRAF, Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor; DC, Dendritic cells; MP, Macrophages; NT, Naïve T cell; IL-10, Interleukin 10 proteins; Tregs, Regulatory T cells; Th1, Type 1 T helper cells; Th2, Type 2 T helper cells; Th17, Type 17 T helper cells; SIgA, Secretory immunoglobulin A; TJs, Tight junctions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diarrhea is the most prevalent enteric disease in modern pig production and leads to high mortality, reduced growth rates and increased treatment costs [1, 2]. Neonatal diarrhea occurring throughout the suckling piglet period and post-weaning diarrhea occurring within the first two weeks after weaning are the two most prominent forms of diarrhea in piglets [3, 4]. After birth, the mucosal immune system of piglets is immature. As a result, pathogens can easily colonize the intestinal tract, leading to the development of neonatal diarrhea. Moreover, the weaning process causes stress in piglets and thus impairs intestinal function, which allows pathogens to develop post-weaning diarrhea. The mortality rate of piglets with diarrhea can increase by up to 75% depending on the severity of diarrhea and the age of piglets [5]. The pre-weaning mortality rate ranges from 10% to 20% in the main pig-producing countries [6], whereas mortality can reach up to 25% due to diarrhea during the post-weaning period [2]. Diarrhea outbreaks in piglets are caused by different enteropathogens such as bacteria, viruses, protozoa, and parasites [7]. Furthermore, non-infectious factors, such as poor nutrition, management and stress, can lead to an increased risk of enteropathogenic infection which causes diarrhea in piglets.

Recently, diarrhea in piglets, particularly that of infectious origin, has regained attention because approximately half (49%) of piglet deaths result from diarrhea infections that cause severe economic losses in the swine industry worldwide [8]. Diarrhea due to bacterial infection is common in piglets. Among the bacteria that cause diarrhea in piglets, the main pathogens are Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp. and Clostridium spp. [9]. Antibiotics are commonly used in the modern pig industry [10]. However, the long-term and overuse of antibiotics in animal diets has led to drug-resistant bacteria in animals and humans [11, 12]. Thus, antibiotics used in animals were banned in the European Union in 2006 [13] or allowed for limited use in many countries such as USA and Japan [11, 14]. Moreover, the use of antibiotics in feed production enterprises to commercial feed as growth promoters in pig production has been banned in China from 2020 [15]. In this context, researchers, farmers, and the pig industries are making substantial efforts to find new alternatives to antibiotics in pig farming. Thus, probiotics, prebiotics, organic acids, enzymes, essential oils, medium chain fatty acids, zinc, and plant extracts have been used as alternatives to antibiotics in in vitro and in vivo studies [16]. Among them, probiotics have been tested or used as a replacement for antibiotics because they can decrease the pathogen load and alleviate gastrointestinal disorder symptoms by restoring the microbial balance in animals [17]. Many of the gut microbes can play immunomodulatory roles in the host. The most frequently used probiotic microorganisms are Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, Bacillus, Pediococcus and yeast genera Saccharomyces for treating diarrhea in piglets as it has recently been well documented in recent years (Tables 1 and 2). Some probiotic strains confer immunological protection to the host by modulating the immune response [18]. These probiotic strains are designed as “immunobiotics” [19]. Thus, exploring and gaining knowledge of the interactions among immunomodulatory probiotics, pathogens, and the host’s gastrointestinal tract during diarrhea in piglets will help develop new probiotics (immunobiotics) that can help to protect animals from diarrhea and enhance growth performance.

The aim of this review was to summarize the evidence for the use of beneficial microbes against diarrhea in piglets, focusing on common bacterial infections to assess how they reduce diarrhea and inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract of piglets. Moreover, this review aims to provide advanced knowledge to probiotic researchers, immunologists, swine nutritionists, and the probiotic industry to critically consider novel preventive approaches when applying or developing immunomodulatory probiotics to control diarrhea in piglets.

Methodology

An electronic database was constructed based on published articles that reported the use of probiotics to control and/or treat bacterial diarrhea in piglets. We searched for articles published between January and March 2023. Articles were retrieved from PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Science Direct databases using the following key words: probiotics, piglets, diarrhea, E. coli, Salmonella, Clostridium, lipopolysaccharides (LPS), and performance. The details of the article selection process of articles for this review are shown in Fig. 1.

Common bacterial pathogens that cause piglet diarrhea

Bacterial pathogens are the most common cause of diarrhea in piglets [70]. The major bacterial pathogens causing diarrhea in piglets are Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp. and Clostridium spp. (Fig. 2).

Visualization of A) E. coli (Enterotoxigenic, ETEC with fimbriae and enterotoxins), B) E. coli (Enteropathogenic, EPEC with intimin), C) Salmonella spp. with their effectors, and D) Clostridium spp. with enterotoxins. Abbreviations: F4, F5, F6, F18, F41, Fimbriae; LT, heat liable toxin; ST, heat stable toxin, EAST, Enteroaggregative heat stable toxin; T3ss, Three secretion systems; CPA, Clostridium perfringens toxin alpha; CPB, Clostridium perfringens toxin beta; ETX, Clostridium perfringens toxin epsilon; ITX, Clostridium perfringens toxin iota; TedA, Clostridium difficile toxin A, TedB, Clostridium difficile toxin B (Created with BioRender.com)

Escherichia coli (E. coli)

E. coli are Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, flagellated bacilli, and members of the Enterobacteriaceae family. They are the predominant etiological agents of a wide range of diseases in pigs, including neonatal and post weaning diarrhea, and are one of the major causes of death worldwide in neonates and weaned pigs respectively [71]. It causes diarrhea in swine, accounting for 56.2% of piglet cases, and is responsible for 24.7% of deaths due to diarrhea [72]. Based on the pathotypes of E. coli that can cause diseases in piglets, enterotoxigenic (ETEC) and shiga toxin producing (STEC) strains comprise two groups: 1) edema disease E. coli and enterohemorrhagic 2) enteropathogenic (EPEC) and extraintestinal pathogenic. Notably, the common categories related to enteric colibacillosis in piglets are ETEC and EPEC (Fig. 2A and B). Enterotoxigenic E. coli is one of the most common categories found in swine and includes different serotypes (different combinations of toxin and fimbriae). In general, diarrhea occurs during neonatal and post-weaning stages through ingestion of these bacteria, attaching to the mucus layer of the small intestine using hair-like structures known as fimbriae (F4, F5, F6, F18, and F41), whereas adhesin is involved in diffuse adherence (AIDA-I) and porcine-attaching effacing factor (Paa) is involved in non-fimbrial attachment. After colonization, ETEC produce enterotoxins that cause neonatal and post weaning diarrhea in piglets. In porcine neonatal diarrhea, most ETEC strains produce heat-stable enterotoxins that bind to the villous brush border guanylyl cyclase C glycoprotein receptor and intestinal crypt, inducing the production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate and leading to fluid and electrolyte secretion [73]. Heat liable toxins produced by ETEC bind to the cell surface and activate the adenylate cyclase system to induce cyclic adenosine monophosphate production. The upregulation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate activates the apical chloride channel and a basolateral Na/K/2Cl cotransporter, resulting in chloride secretion from enterocytes, reduced sodium absorption, and concomitant water loss into the intestine [74]. Excessive fluid loss due to diarrhea causes death eventually in piglets [73]. In post weaning diarrhea in piglets, ETEC strains contain fimbriae in their outer membrane layer, which are hair-like structures responsible for promoting the adhesion of ETEC to the mucosa of the intestine [75]. In addition, non-fimbrial adhesins including AIDA-I and Paa were expressed by ETEC strains, which facilitated the colonization of the intestinal tissue and produce heat-labile, heat-stable, and enteroaggregative E. coli enterotoxins. Enterotoxins have been shown to enhance the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the lumen and influence the expression of tight junction proteins in the intestines of piglets [76]. Inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-17, and TNF-α), chemokines (IL-8, CXCL5, CCL2, and CCL8), and immune cells contribute to inflammation and intestinal damage during ETEC infection [31]. In addition, LPS, a major component of the outer membrane of bacterial cells, induces intestinal damage and diarrhea via an inflammatory response [77].

Enteropathogenic E. coli causes edema and diarrhea in piglets, producing and effacing lesions on intestinal epithelial cells and effacement of enterocyte microvilli [78, 79]. The EPEC pathotype can be categorized into two subgroups: typical and atypical. The EPEC possesses outer membrane proteins called intimin and the Paa which facilitate bacterial attachment to the translocated intimin receptor (Tir) of intestinal cells. Subsequently, the Tir-intimin interaction employed a non-catalytic tyrosine kinase (Nck) adaptor to activate the actin nucleation-promoting factor neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein which is responsible for inflammation and diarrhea [80].

Salmonella spp.

Salmonella is a Gram-negative, motile, rod-shaped, facultative anaerobic bacterium belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family that causes enteric diseases in pigs (Fig. 2C). Approximately 2,000 Salmonella serotypes have been recognized; however, few of them (Salmonella enterica, Salmonella Typhimurium and Salmonella choleraesuis) are responsible for most outbreaks in pigs. Salmonella spp. employs “effector” proteins using Type III secretion systems (T3SSs), which are molecular needle-like structures that allow invasion of effector proteins to the pig intestinal epithelial tissues [81]. The T3SSs secrete protein subunit, “Translocon” which can generate a pore in the membrane of host cell, resulting in virulence effector delivery into host cell, ultimately disrupting the intestinal epithelial cells [82] and dissemination of infection [83]. Upon entry into the host cell, Salmonella induces the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines through pathogen-related molecular patterns, such as peptidoglycan, LPS, and flagellin. Then, Salmonella can rapidly invades the intestinal lamina propria and causes acute inflammatory stimulus [84]. Inflammation in the intestine creates favorable conditions for the growth of Salmonella by altering the composition of the healthy gut microbiota.

Clostridium spp.

The Clostridium genus comprise Gram-positive, rod-shaped, anaerobic, and spore-forming bacteria (Fig. 2D). Clostridium perfringens (serotypes A→G) and Clostridioides difficile commonly cause diarrhea in piglets. Among the seven serotypes (A→G) of C. perfringens, types A and C are the most common causes of diarrhea in piglets. Type A and C strains of C. perfringens produce the enterotoxins CPA, CPB, ETX, and ITX which are involved in creating lesions in the small intestine, and disrupting all layers of the intestinal wall, and inducing inflammatory responses [5]. Disruption of the intestinal wall facilitates the absorption of toxins from the intestine into the blood, leading to toxemia and death of piglets. In addition, toxigenic strains of C. difficile secrete two main toxins, TcdA and TcdB, which are involved in damaging the intestinal cell wall through the inactivation of Rho and Ras GTPases, activating inflammatory responses in the host, leading to an influx of cytokines and neutrophils that provoke intestinal wall and tight junction damage, ultimately leading to diarrhea in piglets [85].

Effect of probiotics (immunobiotics) on pigs’ growth and health

Probiotics are expected to replace antibiotics as growth-promoting therapeutic agents. Thus, research on the use of probiotics is expanding. A single strain or combination of microbial strains have been used to control diarrhea and enhance the growth and health status of piglets (Table 2). Supplementation with probiotics in early life can improve piglet growth and healthy intestinal microbiota. As a result, early administration of probiotics can be a potential strategy to prevent diarrhea and restore microbial balance by establishing a microbiota balance after a transient drop in beneficial microbes, thereby contributing to the defense against disease-causing bacteria, improving nutrient absorption, and stimulating host immunity. Moreover, the morbidity and mortality of pigs decrease and growth performance and health conditions improve because of probiotic supplementation [86]. Several studies (Table 2) were performed to evaluate the effects of different probiotic strains on a wide range of health conditions and growth performances of piglets. Notably, different probiotic treatments using spores to survive and heat-killed microbes improve intestinal health and growth performance, and reduce diarrhea in young piglets. Probiotics have various beneficial health effects through different pathways such as reducing gut pathogens, increasing beneficial microbes in the gut, increasing nutrient absorption, and regulating immune responses. The administration of Lactobacillus enhances a healthier microbial fermentation profile by augmenting beneficial microbes and intestinal barrier function, which is evidence of better nutrient absorption [22, 32, 45]. For example, daily feeding of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Lq80 (1010 cells) for 14 d to weaned piglets (21 days old) resulted in a significant reduction of E. coli and C. perfringens in feces and increased the Lactobacillus population in the intestine [32]. Another probiotic strain, Limosilactobacillus reuteri ZLR003 (2 × 109 CFU/mL), was supplemented to 30-d old weaned piglets for 10 d, and it was found that L. reuteri ZLR003 contributed to healthy microbial fermentation and improved the beneficial microbes in the intestine [45]. Moreover, several Lactobacillus strains, such as Lactobacillus jensenii TL2937 and L. plantarum TL2766, were supplemented to piglets from 3 weeks of age for 14 weeks (until 17 weeks of age) [22]. The study reported no changes in plasma free fatty acids, glucose, triglyceride cholesterol, blood leukocytes, C-reactive protein, lymphocytes, phagocytic activity, or antibody levels between the L. jensenii TL2937 and L. plantarum TL2766 groups. However, L. jensenii TL2937 supplementation reduced the presence of K88, K99, and 987P ETEC strains in the feces whereas L. plantarum TL2766 reduced only 987P ETEC. Moreover, body weight was affected by Lactobacillus administration. These findings suggest that supplementation with L. jensenii TL2937 can improve the health and productivity of pigs. In another study, oral administration of a commercial preparation of a mixture of Limosilactobacillus fermentum and Pediococcus acidilactici (1.6 × 109 CFU/g) to pigs weaned at 28 days old for a period of 28 d improved growth performance, daily gain, and reduced concentration of serum proinflammatory factors, IL-6 and IFN-γ [55]. Additionally, oral administration of 2 mL Limosilactobacillus frumenti JCM11122 (108 CFU/mL) from 6–10 d prior to early weaning improves health promoting microbes by altering the intestinal microbial community, which leads to improved fatty acid and protein metabolism and also reduces disease-associated metabolic pathways. Improve intestinal integrity, and tight junction proteins (such as occludin, ZO-1 and claudin), and intestinal secretory IgA and IFN-γ levels by L. frumenti JCM11122 supplementation were reported [50]. Similarly, another probiotic strain, Lactobacillus delbrueckii CCTCCM207040 (5 × 108 CFU/mL), was supplied at different doses (1, 2, 3, and 4 mL) to suckling piglets for 14 d, resulting in improved body weight, concentration of serum IgG, and anti-inflammatory cytokines with reduced incidence of diarrhea [51]. In a recent study, 18 days of intragastric supplementation with Lactobacillus johnsonii L531 (1 × 1010 CFU/d) in weaned piglets challenged with Salmonella Infantis reduced the severity of diarrhea and inflammation in the intestine and maintained intestinal homeostasis [58]. Probiotic supplementation in the form of heat-killed Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus at doses of 0.1%, 0.2%, and 0.4% with diet in weaned piglets improved growth performance, modulated the immune response, and alleviated post weaning diarrhea [62]. On oral administration of L. plantarum N14 supplemented with Rakky pickles at different dose levels (5%, 20%, and 40%) in piglets showed that 5% or 20% dose level improved complement activity, phagocytic activity, and leukocyte count in the peripheral blood compared with those using a 40% dose or untreated controls. Moreover, the piglets that received L. plantarum N14-fermented Rakky pickle juice exhibited higher growth rates than controls [64].

Additionally, different probiotics from Bacillus strains improve growth performance and immunomodulation [61]. Bacillus spp. secrets enzymes that improve feed digestibility and promote animal growth. Providing Bacillus subtillis KN-42 (20 × 109 CFU/kg feed) to weaned piglets for 28 d improved growth performance and average daily gain and reduced the diarrhea index and number of E. coli in feces [40]. In addition, the administration of a commercial preparation of B. coagulans (600 g/t) to weaned piglets for 28 d resulted in improved body weight, daily weight gain and reduced the incidence of diarrhea [66]. Wang et al. [61] showed that feeding a mixture of Bacillus licheniformis and B. subtilis (4 × 109 CFU/g) for 42 d had a positive effect on piglet intestinal immunity by modifying the gut microbiota composition and concentration of microbiota-derived metabolites. Feeding complex probiotics (multi-species probiotic formulations), a mixture of different strains of Lactobacillus, Bacillus, Saccharomyces genera, with different compounds improve the health status and growth performance of piglets [33, 41, 49, 54, 60, 63]. Supplementation of 0.5% probiotics (Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. plantarum, B. subtilis and S. cerevisiae) with green tea to pigs for 28 d improved growth performance, and splenocyte production of IL-6 and TNF-α [33]. This may be due to the increased activity of different gastrointestinal enzymes, such as sucrase, lipase, protease trypsin, and chymotrypsin [50], and reduced intestinal permeability [53] by supplementation with probiotic bacterial species of the genera Lactobacillus and Bacillus, which leads to gastrointestinal peristalsis and promotes apparent digestibility [62, 87].

Furthermore, yeast can produce enzymes, such as amylase and galactosidase, which play vital roles in nutrient utilization and improve animal growth performance. Yeast can also regulate the intestinal microbial balance, strengthen the immune system, and improve animal health. Administration of S. cerevisiae S288c strain (2 × 108 CFU/mL) fermented with egg white powder (Duan-Nai-An) for 10 d improved the intestinal structures and lymphoid tissues, and promoted improvements in the intestinal health in weaned piglets [57]. Feeding live yeast S. cerevisiae NCYC Sc 47 to nursery pigs for 45 d improved growth performance and body weight, and decreased E. coli concentration in pig feces [88].

Probiotics against bacterial pathogens causing diarrhea in piglets

Recently, many researchers have evaluated the use of probiotics in prevention and treatment of various diseases of piglets [15, 89,90,91]. Evidence suggests that probiotics act as immune activators, particularly by boosting host immunity against pathogenic bacteria. Additionally, probiotics defend the intestinal tract by competitively excluding pathogenic bacteria that cause intestinal inflammation and diarrhea [15]. Moreover, probiotic use can reduce inflammation, restore barrier function, and mitigate the gut dysbiosis associated with diarrhea. Some probiotic genera (Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Bacillus, Enterococcus and Saccharomyces) act as immunomodulators, regulate the proliferation and differentiation of lymphocytes (T and B cells), induce the secretion of cytokines and chemokines, and stimulate immune responses against bacteria in piglets [92]. The microorganisms that have been used as probiotics against pathogenic bacteria-induced piglet diarrhea are presented in Table 1 and 2.

In vitro studies of probiotics against bacterial diarrhea in piglets

Some studies examined the effects of probiotics on bacterial pathogens using in vitro cell culture models (Table 1). Based on these findings, probiotic genera (Lactobacillus and Bacillus) may regulate immune response and antagonistic activity against bacterial pathogens, including E. coli and S. enterica. In the intestine, probiotic strains adhere to intestinal epithelial cells and modulate the intestinal immune system. The interactions between microbes and intestinal epithelial cells play a vital role in the regulation of several immunological functions in the gut. Thus, evaluating the anti-inflammatory activity of probiotic strains on porcine intestinal epithelial cells is useful for selecting immunobiotics [90]. Porcine intestinal epithelial (PIE) cells are used in vitro to evaluate the immunoregulatory mechanisms of immunobiotics against pathogens causing diarrhea in piglets, and several established PIE cell lines (PIE, IPEC-1, and IPEC-J2) have been used to study the potential probiotics against bacterial pathogens causing diarrhea in piglets (Table 1). Our research group used PIE cells because they are a useful cell line for studying inflammatory responses via toll-like receptors (TLRs) in epithelial cells. We tested the different strains of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium genera, such as Lactobacillus jensenii TL2937; Ligilactobacillus salivarius FFIG35, FFIG58; L. plantarum CRL1506, CRL681; Limosilactobacillus reuterii MEP221102, L. rhamnosus MEP221111; L. salivarius isolates; L. fermentum UCO-979C, CRL973; L. delbrueckii subsp. delbrueckii TUA4408L; Bifidobacterium breve M-16 V, Bifidobacterium longum BB536 [20,21,22,23, 27,28,29, 31] for studying their interaction with PIE cells, and found that different probiotic strains can differentially modulate the inflammatory response and produce different inflammatory factors in response to E. coli and E. coli-rotavirus superinfection. In vitro, strains CRL1506 and CRL681 regulated the gene expression of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6) and chemokines (IL-8, CCL2, CXCL5, and CXCL9) in ETEC-stimulated PIE cells. Baillo et al. [31] reported that ETEC challenged PIE cells treated with L. plantarum CRL1506 or CRL681 downregulate the gene expression of IL-8, CCL2, CXCL5, CXCL9, A20 and Bcl-3 by interference with inflammatory signaling pathways such as nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK). Another study revealed that L. jensenii TL2937 downregulated the expression of IL-6 and IL-8 in PIE cells treated with ETEC [20] and in a co-culture of PIE and antigen-presenting cells stimulated with ETEC [22]. In addition, this strain led to the upregulation of negative regulators (A20, Bcl-3 and MKP-1) of TLR4 in PIE cells, resulting in a marked decrease in inflammatory responses in PIE cells. Similar results were found for some L. salivarius isolates, which decreased the expression of IL-6 in PIE cells challenged with ETEC [27]. While L. fermentum UCO-979C able to reduce inflammatory chemokines (CXCL8, CXCL-10 and CXCL-11) in ETEC stimulated PIE cells by regulating the NF-κB pathway [28]. Notably, L. fermentum CRL 973 also reduces the expression of CXCL-5 in ETEC stimulated PIE cells. Another study by our research group using PIE cells challenged with ETEC showed that L. delbrueckii TUA4408L inhibits the activation of MAPK and NF-κB pathways and the subsequent production of IL-6, IL-8 and MCP-1 and reduce the inflammation [23]. In addition, a study of different Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria strains demonstrated that individual strains have different effects on the inflammatory response in ETEC-stimulated PIE cells. Particularly, Bifidobacterium longum BB536 and Bifidobacterium breve M-16 V strains reduce the expression of IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 expressions in ETEC challenged PIE cells by modulating the MAPK and NF-κB pathways [21]. Similar to our results, L. reuteri LR1 decreased the expression of proinflammatory transcripts (IL-6 and TNF-α) and increased the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10) in IPEC-1 cells after challenge with ETEC 0149:K91 and K88ac [24]. In addition, the findings of Zhang et al. [25] showed that L. rhamnosus GG could inhibit S. enterica serovar Infantis invasion in IPEC-J2 cells and Salmonella Infantis induced autophagy. L. johnsonii LJ202 and L. reuteri LR 108 completely inhibited the growth of S. enterica serovar Enteritidis DMST7106 in co-culture. B. subtilis CP9 strain was shown to increase anti-inflammatory granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor and host defense peptides (such as mucin 1) and decrease the proinflammatory TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and TLRs mRNA expression levels in IPEC-J2 cells in response to E. coli challenge [26].

In vivo studies of probiotics against bacterial diarrhea in piglets

Probiotics against E. coli pathogen

Oral supplementation with probiotics may prevent or improve diarrhea in piglets as summarized in Table 2. Lactobacillus species are used as feed additives and contribute to a balanced gut environment in various ways, such as protection against pathogens, improvement of intestinal health, and stimulation of immune responses. When L. plantarum CGMCC1258 is orally administered orally to ETEC-challenged piglets, it increases the expression of the genes for tight junction proteins (ZO-1 and occludin), indicating an increase in strength of the intestinal epithelial barrier [39]. In addition, serum TNF-α production was markedly decreased in L. plantarum JC1 (B2028) treated animals [37]. A 28-d trial of oral administration of L. plantarum CJLP243 down regulated IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ levels in serum and reduced acute inflammation of the gut after E. coli infection [35]. Another study by Sun et al. [59] reported that a newly isolated L. salivarius strain inhibited the expression of proinflammatory mediators (IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ, and TNF-α) in the serum and TLRs, such as TLR2 and TLR4 mRNA expression in the spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes after stimulation with LPS derived from E. coli serotype O55:B5. Moreover, supplementation with L. salivarius strain increased anti-inflammatory cytokines in the serum and epithelial tight junction proteins (claudin, occludin, and ZO-1) in the LPS-challenged pig intestine [59]. Improved mucosal immunity and IgA levels in the serum and ileum were also observed with a dietary supplement of Limosilactobacillus mucosae LM1and a mixture of L. mucosae LM1 and mannon oligosaccharides in LPS-challenged piglets [63].

Probiotics containing different strains or species have different efficacies in controlling or treating bacterial infection-related diarrhea in piglets [53]. Bacillus species can be used as feed additives in pellets because of their ability to survive under the low pH and harsh conditions in the gut. Bacillus species produce antimicrobial substances that kill pathogenic microorganisms and protect the intestines from pathogen invasion [93]. Yang et al. [44] reported that B. licheniformis (DSM 5749) and B. subtilis (DSM 5750) spores improved the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier by improving the jejunal ZO-1 protein expression and upregulated the intestinal TLR4, NOD2, iNOs, IL-8 and IL-22 and IκBα mRNAs expression and peripheral blood CD4−CD8− T-cell in ETEC induced piglets. Furthermore, it was found that the oral administration of B. licheniformis (DSM 5749) and B. subtilis (DSM 5750) increased the production of CD4+Foxp3 T regulatory cells and CD4+IL-10+ T cells in the intestine to maintain the barrier integrity and protect the intestine from infectious agents in F4ab/acR− (F4 fimbriae receptor negative) pigs challenged with an F4+ ETEC/VTEC/EPEC strain [42]. The same probiotic species with different strains namely B. licheniformis HJ0135 also has been used in a 28-d trial, where it was found to improve immune function and provide a positive effect by increasing the immunoglobulin (Ig) A concentration in serum and jejunum mucosal IgA and IgG, and decreasing serum IL-6 and jejunum mucosal IL-1β in response to E. coli LPS challenge [69]. Similarly, Cao et al. [68] reported that probiotic strain B. licheniformis GCMCC23776 enhanced the serum concentrations of IgA, IgG, and IgM in E. coli LPS-challenged weaned piglets.

Another notable study observed that the supplement of Enterococcus faecium R1 diminishes the injury in the intestine and liver of LPS-challenged piglets by increasing the glucagon in plasma and IL-1β in the liver. Moreover, the mRNA expression of villin in jejunum and ileum, and Bcl-xL and pBD-1 expression in the ileum were upregulated by supplementation E. faecium R1. However, E. faecium R1 supplemented group reduced prostaglandin 2 and malondialdehyde content in the liver compared with that in the control group [65].

Additionally, using S. cerevisiae as a feed additive to E. coli challenged piglets activated the intestinal immune genes and improved body weight gain by increasing beneficial bacteria in the gut and reducing intestinal impairment [34, 48]. Supplementation with the S. cerevisiae CNCMI-4407 strain ameliorated the diarrhea and increased the concentration of IgA in the serum of piglets challenged with ETEC [38].

Probiotics against Salmonella pathogen

Oral administration of L. plantarum B298 to the S. Typhimurium-challenged piglets enhance the innate immune response by accentuating the immunoglobulin levels in the serum [43]. Similarly, the supplementation of L. rhamnosus GG controls enteric infection by restoring the gut microbiota balance and increasing the CD3-CD19-T-bet + IFN-γ + and CD3-CD19-T-bet + IFN-γ- cell population to maintain homeostasis in the intestine of S. enterica serovar Infantis-challenged in piglets [52]. The addition of Bifidobacterium strains such as, Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BPL6 and Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis CECT 7210 in the diet can improve intestinal immune function by enhancing intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes in Salmonella Typhimurium challenge piglets [47]. A positive effect on the piglets health was observed by the oral supplementation of B. cereus var Toyoi by reducing the frequenting of CD8 + γδ T cells in the peripheral blood and gut epithelium in piglets challenged with S. Typhimurium [36].

Multi-strain probiotics can enhance intestinal immunity by modulating the immune responses in the intestine. The combination of L. johnsonii L531, B. licheniformis BL1721, and B. subtilis BS1715 improved the expression of tight junction proteins (claudin 1, caspase-1) in the gut of piglets challenged with Salmonella Infantis [53]. Furthermore, a study using the mixture of probiotics containing Lactobacillus amylovorus P1, L. mucosae P5, and E. coli Nissle 1917 for oral administration showed that the combination had a positive effect on reducing clinical signs and inflammatory responses in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2-challenged piglets [54]. Another L. acidophilus strain W37, and inulin were assayed as vaccines for their efficacy against multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium-challenged piglets, and it was observed that feed efficiency and fecal consistency were improved the vaccination with L. acidophilus W37 and inulin supplementation [56].

Probiotics against mixed infection and Clostridium

Feeding a mixture of probiotic strains, namely L. plantarum LA, P. pentosauceus SMFM2016-WK1, P. acidilactici K, and L. reuteri PF30 to piglets challenged with E. coli and S. enterica resulted in beneficial effects on growth performance and reduced E. coli and S. enterica counts in feces [67]. Another study using a commercial probiotic Lactobacillus spp. product against C. difficile found a reduction in pathogen-induced mesocolonic edema; however, its effect on disease control in piglets remained unclear [46]. Therefore, the oral administration of probiotics has the potential to prevent and improve bacterial infections that can cause diarrhea in piglets. Most studies have focused on the use of probiotic strains against bacterial challenges in piglets, and more field studies on commercial pig farm conditions are necessary to determine the precise probiotic strains and dosages to control piglet diarrhea.

Mechanisms of action of probiotics to alleviate piglet diarrhea

Although the precise mechanism of action of probiotics in the treatment of piglet diarrhea is not fully understood, two probable mechanisms have been proposed: regulation of the intestinal microbial barrier (Fig. 3) and the improvement of the immune system (Fig. 4).

Interaction of probiotics on the intestinal barrier and its application in treating in piglets diarrhea. Probiotics alleviate diarrhea by regulating the intestinal microbial and mucosal barrier: 1) competitive exclusion of pathogen, 2) producing antimicrobial substance and neutralize toxins, 3) restore beneficial microbes, 4) upregulation of intestinal tight junction protein expression, 5) stimulate the secretion of mucin and peptides, and 6) reduce pH in intestine and helps to maintain normal intestinal permeability. Abbreviations: SCFAs, Short chain fatty acids (Created with BioRender.com)

Probiotic modulation of gut associated immune system through TLR pathway regulation. Both pathogenic (red) bacteria (ETEC/Salmonella/Clostridium) and probiotic (green) bacteria can express similar/overlapping profiles of PAMPs/MAMPs (LTA, LPS, Flagellin) through a range of PRRs including TLR2, TLR4, TLR5. All of which can transduce immune activatory/inflammatory responses through activation of NFkB and MAPK signal pathways (indicated in black arrows). Probiotic-derived MAMPs (indicated as green), induce a suppressive/tolerogenic response via the induction of endogenous negative regulators to TLR signals (Tollip, IRAK-M, Myd88s, A20, Bcl3 and MKP-1) that inhibit NFkB and MAPK pathways. Abbreviations: LPS, Lipopolysaccharide; PAMPs, Pathogen-associated molecular patterns; MAMPs, Microbial associated molecular patterns; TLR2, Toll like receptor 2; TLR4, Toll like receptor 4; TLR5, Toll like receptor 5; TIRAP, Toll-interleukin-1 Receptor domain containing adaptor protein; TRAM, Translocating chain associating membrane protein; MyD88, Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88; IRAK-M, Interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase M; TRAF6, Tumor necrosis factor associated factor 6; MAPK, Mitogen activated protein kinase; IκBα, IkappaB alpha; JNK, c-JUN N-terminal kinase; ERK, Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; p38, 38 kDa protein; NF-κB, Nuclear factor kappa B; A20, Tumor necrosis factor-α-inducible protein 3; Bcl3, B-cell lymphoma 3-encoded protein; MKP-1, Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (Created with BioRender.com)

Probiotics and the intestinal barrier

The intestinal barrier acts as a major defense against pathogen invasion and maintains epithelial integrity and gut functionality. Newborn piglets develop diverse microbial communities in the gastrointestinal tract by consuming milk and exposure to the external environment. The dynamic balance of different gut microbiota acts as the first barrier to the gut. The mucosal layer serves as a protective barrier against pathogenic microorganisms, antigens, toxins, and other harmful substances. The mucosal layer acts as a protective barrier, which mainly comprises chemical and mechanical barriers [15, 94]. The chemical barrier consists of a mucosal layer and different digestive liquids (intestinal juices and enzymes) that are released by the mucosal epithelium of the intestine. Paneth and goblet cells, which reside in the intestine, play an important role in natural immune defense and support the intestinal barrier function [95]. Paneth cells produce different antimicrobial factors including, lysozyme, CRP-ductin, and α and β defensins [96] and these factors can disrupt the membranes or cell wall to kill the pathogenic bacteria and maintain homeostasis in the intestine [97, 98]. Additionally, intestinal goblet cells release mucin to form a protective layer of mucus at the top of the intestinal epithelial cells, preventing the entery of pathogenic bacteria into the epithelial barrier [99]. Mucins are glycoproteins that contribute to the maintenance of gut homeostasis and protect the intestinal barrier by interacting with the immune system. Interaction between intestinal microbes and host immune defense cell can subtly modulate intestinal barriers to prevent the invasion of pathogenic microbes and prevent inflammation in the intestine. This mechanical barrier is composed of various epithelial cells and intercellular tight junctions [15]. Intestinal epithelial cells and tight junctions effectively act as barriers to the invasion of bacteria and endotoxins from the intestine into the blood stream [100, 101].

Neonatal diarrhea occurs in piglets that do not receive colostrum and are born from non-vaccinated pigs. Some disease producing bacteria, such as E. coli, and Clostridium spp. can rapidly colonize the intestines of neonatal piglets, causing diarrhea, because the digestive and immune systems of piglets are not developed properly at this stage. After the neonatal stage, when weaning occurs, piglets tend to develop microbial diversity in the gastrointestinal tract because of abrupt changes in diet from milk to solid feed [102]. The gut microbial balance is formed based on feeding and maintains mutual relationships among different gut microbes, which acts as the first barrier of the gut against pathogens. During weaning, piglets experience stress that disrupts the intestinal barrier functions, which may result in the leakage of pathogenic microorganisms into the internal tissue layers, which in turn can cause inflammatory bowel diseases, such as diarrhea [103]. The consumption of probiotic bacteria involves the maintenance of intestinal barrier function; however, the mechanism by which probiotics maintain barrier function is not well understood. Probiotic supplements competitively prevent the adhesion of pathogenic microorganisms and exclude pathogens by producing antimicrobial substances in the intestine [61]. Probiotics stimulate paneth and goblet cells present in the intestinal epithelial layer, resulting in the production of mucins and antimicrobial substances that inhibit pathogen adhesion and kill pathogenic bacteria [104]. Moreover, probiotics can produce short-chain fatty acids in the gut, which contribute to lower pH levels in the intestine and enhance the gut barrier function by providing energy to intestinal epithelial cells [105], thereby inhibiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria [106]. Notably, probiotics can influence bacterial colonization by excluding or reducing pathogenic bacteria in the intestine and maintaining an optimal balance of the gut microbiota [103]. Probiotics secrete antimicrobial substances, such as bacteriocins and hydrogen peroxide to inhibit the adhesion of pathogens to the intestinal mucosa [107]. Probiotic supplementation upregulates intestinal integrity and expression of tight junction proteins that are damaged by pathogenic bacteria [108]. Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Bacillus, and Enterococcus strains enhance intestinal barrier function in piglets challenged with ETEC [109]. In addition, probiotics, and their metabolites (such as organic acids, mannan oligosaccharides and β-glucan of yeast cell) may act as immune activators, which can stimulate the proliferation of T and B lymphocytes and the secretion of cytokine and chemokines and generate a series immune response [110].

In summary, the protection of the intestinal barrier in piglets may be improved by probiotic supplementation. However, the specific regulatory mechanism of probiotics on the intestinal barrier in piglets to alleviate diarrhea requires further research.

Probiotics and the immune system

The immune system protects the host by segregating pathogenic and non-pathogenic microbes through different responses. Intestinal epithelial and gut-associated immune cells recognize molecules frequently found in bacteria via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). PRRs are activated by specific pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which include various microbial components, such as LPS, peptidoglycan, flagellin, and bacterial DNA/RNA. Among the different families of PRRs, TLRs have been well studied and are expressed on diverse immune cells, such as B, macrophage, natural killer, dendritic, fibroblast, and non-immune cells, such as epithelial and endothelial cells [111]. TLRs play a prominent role in activating innate immunity and creating a link with adaptive immunity by modulating the functions of antigen-presenting cells and key cytokines [112]. Among the various TLRs, TLR4 recognizes and binds to LPSs, whereas TLR2 recognizes different PAMPs of pathogens (lipoprotein, peptidoglycans, lipoteichoic acids, zymosan, and mannan). TLR5 recognizes the flagellins in bacteria [113]. This compound is considered a potent inducer of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Although this response is considered the prime line of defense, prolonged and dysregulated responses may lead to tissue damage and dysfunction. In general, upon infection with bacteria or viruses, TLRs are activated and bind to their specific cognate ligands, resulting in the expression of peripheral membrane proteins, such as Toll-interleukin-1 Receptor domain containing adaptor protein (TIRAP) and Translocating chain associating membrane protein (TRAM) [111]. These adaptor proteins are involved in surveying the inner leaflets of the plasma-endosomal membrane [111]. TIRAP and TRAM can further recruit different negative regulators, such as myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88), interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase M (IRAK-M), Toll- interacting protein, A20 and Bcl3 [97, 113]. IRAK-M heterodimerize with IRAK1- IRAK-2 and bind to My88 and tumor necrosis factor-associated factor 6 (TRAF 6). Upon formation of this MyD88 adaptor complex which leads to activate IκB kinase and MAPK signaling pathways. After activation of IκB kinase and MAPK pathways resulting activation of JNK, ERK, p38 and NF-κB, which leading to induction of inflammatory cytokines [97]. Similar to TLRs, NOD-like receptors are another class of PPRs, which are cytoplasmic proteins that act as innate immune sensors to detect cytoplasmic pathogens [114]. Other types of PRRs include C-type lectin receptors, formaldehyde peptide receptors, retinoic acid inducible-like helicases, and intracellular IL-1 converting enzyme protease activating factor [115]. The supplementation of probiotics and their derived metabolites (such as organic acids, mannan oligosaccharide, and β-glucan of yeast cells) act as immune activators, which can trigger the dendritic cells, monocytes/macrophages, and lymphocyte, stimulating the secretion of a series of cytokines and regulating the immune responses [110]. Supplementation with probiotic bacteria can initiate responses via microbe associated molecular patterns (MAMPs). In fact, probiotics can tolerate immune signaling through different pathways, such as antagonism of pathogen-derived PAMPs, downregulation of PRRs, induction of suppressive cytokines, activation of antagonistic pathways, modulation of TLR negative regulators such as A20, Tollip, Bcl3, and MKP-1, and cross-regulation of TLR signaling [116]. L. plantarum CRL1506 and CRL681 can protect against inflammation-mediated damage in ETEC-challenged PIE cells by modulating the expression of the negative regulators A20, Bcl3, IRAK-M, and MKP-1 in the TLR signaling pathway [31]. The probiotic L. jensenii TL2937 upregulates the A20, Bcl3, and MKP-1 expression in PIE cells [97]. A20 is a zinc protein responsible for suppression of NF-κB signaling in response to TNF-α and microbial molecules LPS [117]. In addition, Bcl-3 protein acts as an inhibitor of NF-κB activity, whereas IRAK-M plays a crucial role in immune regulation through negative feedback loop by reducing the NF-κB and MAPK signaling [118]. In our earlier studies, using PIE cells exhibited a downregulation in the activation of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways and expression of several inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in ETEC-challenged PIE cells preventively stimulated with L. jensenii TL2937 [20], or Bifidobacterium breve M-16 V and Bifidobacterium longum BB536 [21]. Another recent study demonstrated that B. subtilis CP9 lowered the mRNA expression of TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 in IPEC-J2 cells co-incubated with CP9 and ETEC [30]. Moreover, pigs fed a diet with a probiotic mixture containing B. subtilis DSM 5750 and B. licheniformis DSM 5749 showed improved T cell regulation in the intestines of ETEC-challenged piglets [42]. Regulatory T cells play a pivotal role in the production of IgA antibodies, which play protective role against pathogens and toxins and prevent their invasion of the intestinal epithelium [28]. These findings demonstrate that the use of probiotic strains with immunomodulatory capacity could be an effective strategy for controlling or treating diarrhea in piglets.

Further research using multi-omics approaches may be useful to further investigate the mode of action of probiotic supplementation as well as their immunoregulatory capacity against bacterial diarrhea in piglets.

Limitations of probiotics supplement

Research over the last decade has shown that probiotic supplements have positive effects on the health of pigs, but the conditions under which probiotics have been assessed are highly variable. Most studies have described the beneficial effects of probiotics rather than their adverse effects. Considering recently published data, probiotics may have a positive effect on the pathogenic bacteria responsible for diarrhea in piglets. Marked improvements, such as comparison with antibiotics and elimination of pathogens from the host, have not yet been reported. There are also some important differences in the experimental design of the studies, such as the age of piglets, treatment concentration, dosing amount, and methods, or other aspects, such as genetics, sanitary status, treatment days, or diets (Table 2). Furthermore, recently published articles have reported that probiotics can interact with commensal bacteria; however, their interactions have not yet been fully elucidated. Thus, understanding the interactions between probiotics and commensal bacteria is a major challenge for future research. Other strategic challenges are to determine their mechanisms, explicate which probiotic strain can work more specifically against which disease condition, and define the intake levels/doses needed to achieve the effects [119, 120]. An important limitation of probiotics is their ability to survive under during storage conditions. Thus, different environmental factors, such as temperature, humidity, acidity, and air should also be considered during probiotic storage. Otherwise, probiotic survival and the capacity to colonize the gut can be affected [121]. Regulations for the use of probiotics have been proposed by the European Food Safety Authority, and these beneficial microorganisms are considered zootechnical additives at the regulatory level [122]. Therefore, we may not have included or expected the same effects of probiotics as those of antibiotics. We can consider the use of probiotics as feed additives and combine them with other feed additives and management tactics with a more holistic approach [123].

Conclusions

The use of probiotics and testing for their ability to prevent and treat bacterial diarrhea in piglets are increasing; consequently, they are being considered potential alternatives to antibiotics. We reviewed the research status of using probiotics to prevent or treat bacterial diarrhea in piglets and identified their potential regulatory mechanism from the perspective of intestinal barriers and the immune system. In contrast to antibiotics, probiotics commonly play a role in bacterial diarrhea by restoring the microecological balance in the intestine and regulating the function of the intestinal and immunological barriers. Different probiotic strains of the Lactobacillus group and Bacillus, Enterococcus, and Saccharomyces genera exert different health-regulatory effects to prevent or treat diarrhea caused by E. coli, Salmonella, and Clostridium in piglets by eliminating pathogenic microorganisms, producing antimicrobial substances, and degrading toxins, improving gut barrier function, and fostering proliferation, differentiation, and regulation of intestinal immune cells. More experiments (in vivo or in vitro) should be conducted to determine potential probiotics from normal weaned healthy piglets that can steadily colonize the piglet’s gut, improve gut mucosal barrier function, and activate the immune system to prevent diarrhea. In addition, the mechanism by which probiotic supplementation accelerates the maturation of intestinal microbiota or maintains homeostasis in the intestine during diarrhea in piglets warrants further investigation. Future studies should explore the specific effects of probiotic strains, address their viability and stability, and rationally design them to combat diarrhea in piglets.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- aEPEC:

-

Atypical enteropathogenic

- AIDA-I:

-

Adhesin involved in diffuse adherence

- A20:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-α-inducible protein 3

- Bcl-3:

-

B-cell lymphoma 3-encoded protein

- Bcl-xL:

-

B-cell lymphoma-extra large

- CD4:

-

Cluster of differentiation 4

- CD8:

-

Cluster of differentiation 8

- CCL2:

-

Chemokine ligand 2

- CCL8:

-

Chemokine ligand 8

- CPA:

-

Clostridium perfringens alpha toxin

- CPB:

-

Clostridium perfringens beta toxin

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CXCL5:

-

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5

- CXCL8:

-

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 8

- CXCL9:

-

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9

- CXCL10:

-

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10

- CXCL11:

-

Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11

- E. coli :

-

Escherichia coli

- EPEC:

-

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli

- ERK:

-

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- ETEC:

-

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli

- ETX:

-

Clostridium perfringens epsilon toxin

- GTPases:

-

Guanosine triphosphatases

- IFN-γ:

-

Interferon gamma

- IgA:

-

Immunoglobulin A

- IgG:

-

Immunoglobulin G

- IgM:

-

Immunoglobulin M

- IκB :

-

IkappaB

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin-6

- IL-8:

-

Interleukin-8

- IL-17:

-

Interleukin-17

- IL-22:

-

Interleukin-22

- IPEC-1:

-

Intestinal porcine epithelial cell line-1

- IPEC-J2:

-

Intestinal porcine epithelial cell line-J2

- ITX:

-

Clostridium perfringens Iota toxin

- IRAK-M:

-

Interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase M

- JNK:

-

C-JUN N-terminal kinase

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen activated protein kinase

- MCP-1:

-

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

- MKP-1:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1

- mRNA:

-

Messenger ribonucleic acid

- MyD88 :

-

Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88

- Nck:

-

Non-catalytic tyrosine kinase

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear facto kappa B

- NOD:

-

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain

- Paa:

-

Porcine attaching factor

- PAMPs:

-

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- pBD-1:

-

Porcine beta defensin 1

- PIE:

-

Porcine intestinal epithelial

- PRRs:

-

Pattern-recognition receptors

- Rho:

-

Ras homologous

- Ras:

-

Guanosine-nucleotide binding protein

- tEPEC:

-

Typical enteropathogenic

- TIRAP:

-

Toll-interleukin-1 receptor domain containing adaptor protein

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- TRAM:

-

Translocating chain associating membrane protein

- Tir:

-

Translocated intimin receptor

- T3SSs:

-

Type III secretion systems

- TcdA:

-

Clostridium difficile toxin A

- TcdB:

-

Clostridium difficile toxin B

- TLR:

-

Toll-like receptor

- TRAF6:

-

Tumor necrosis factor associated factor 6

- VTEC:

-

Verotoxigenic Escherichia coli

- ZO-1:

-

Zonula occludens-1

References

Rhouma M, Fairbrother JM, Beaudry F, Letellier A. Post weaning diarrhea in pigs: risk factors and non-colistin-based control strategies. Acta Vet Scand. 2017;59:31.

Sjölund M, Zoric M, Wallgren P. Financial impact of disease on pig production. Part III. Gastrointestinal Disorders. Proceedings of 6th European Symposium of Porcine Health Management. Italy, Sorrento: Printed by Litografia La Ducale srl Parma; 2014. p. 189.

Holland RE. Some infectious causes of diarrhea in young farm animals. Some infectious causes of diarrhea in young farm animals. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:345–75.

Luppi A, D’Annunzio G, Torreggiani C, Martelli P. Diagnostic approach to enteric disorders in pigs. Animals. 2023;13:338.

Jacobson M. On the infectious causes of neonatal piglet diarrhoea—a review. Vet Sci. 2022;9:422.

Muns R, Nuntapaitoon M, Tummaruk P. Non-infectious causes of pre-weaning mortality in piglets. Livest Sci. 2016;184:46–57.

Kylla H, Dutta TK, Roychoudhury P, Subudhi PK. Coinfection of diarrheagenic bacterial and viral pathogens in piglets of Northeast region of India. Vet World. 2019;12:224.

Yang Q, Huang X, Zhao S, Sun W, Yan Z, Wang P, et al. Structure and function of the fecal microbiota in diarrheic neonatal piglets. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:502.

Yue S, Li Z, Hu F, Picimbon JF. Curing piglets from diarrhea and preparation of a healthy microbiome with Bacillus treatment for industrial animal breeding. Sci Rep. 2020;10:19476.

Pan L, Zhao PF, Ma XK, Shang QH, Xu YT, Long SF, et al. Probiotic supplementation protects weaned pigs against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88 challenge and improves performance similar to antibiotics. J Anim Sci. 2017;95:2627–39.

Ma F, Xu S, Tang Z, Li Z, Zhang L. Use of antimicrobials in food animals and impact of transmission of antimicrobial resistance on humans. Biosaf Health. 2021;3:32–8.

Xu C, Kong L, Gao H, Cheng X, Wang X. A review of current bacterial resistance to antibiotics in food animals. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:822689.

Martin MJ, Thottathil SE, Newman TB. Antibiotics overuse in animal agriculture: a call to action for health care providers. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:2409–10.

Ghimpețeanu OM, Pogurschi EN, Popa DC, Dragomir N, Drăgotoiu T, Mihai OD, et al. Antibiotic use in livestock and residues in food—a public health threat: a review. Foods. 2022;11:1430.

Su W, Gong T, Jiang Z, Lu Z, Wang Y. The role of probiotics in alleviating postweaning diarrhea in piglets from the perspective of intestinal barriers. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:883107.

López-Gálvez G, López-Alonso M, Pechova A, Mayo B, Dierick N, Gropp J. Alternatives to antibiotics and trace elements (copper and zinc) to improve gut health and zootechnical parameters in piglets: a review. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2021;271:114727.

Raheem A, Liang L, Zhang G, Cui S. Modulatory effects of probiotics during pathogenic infections with emphasis on immune regulation. Front Immunol. 2021;12:616713.

Ara A, Uddin MJ, Saha S, Khan MH, Baset MA. Intervention of fruit juice in yoghurt preparation. Isesco J Sci Technol. 2015;11:30–5.

Villena J, Kitazawa H. Editorial: Immunobiotics interactions of beneficial microbes with the immune system. Front Immunol. 2017;8:580.

Shimazu T, Villena J, Tohno M, Fujie H, Hosoya S, Shimosato T, et al. Immunobiotic Lactobacillus jensenii elicits anti-inflammatory activity in porcine intestinal epithelial cells by modulating negative regulators of the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Infect Immun. 2012;80:276.

Tomosada Y, Villena J, Murata K, Chiba E, Shimazu T, Aso H, et al. Immunoregulatory effect of bifidobacteria strains in porcine intestinal epithelial cells through modulation of ubiquitin-editing enzyme A20 expression. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59259.

Suda Y, Villena J, Takahashi Y, Hosoya S, Tomosada Y, Tsukida K, et al. Immunobiotic Lactobacillus jensenii as immune-health promoting factor to improve growth performance and productivity in post-weaning pigs. BMC Immunol. 2014;15:24.

Wachi S, Kanmani P, Tomosada Y, Kobayashi H, Yuri T, Egusa S, et al. Lactobacillus delbrueckii TUA 4408 L and its extracellular polysaccharides attenuate enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-induced inflammatory response in porcine intestinal epitheliocytes via Toll-like receptor-2 and 4. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2014;58:2080–93.

Wang Z, Wang L, Chen Z, Ma X, Yang X, Zhang J, et al. In vitro evaluation of swine-derived Lactobacillus reuteri: probiotic properties and effects on intestinal porcine epithelial cells challenged with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;26:1018–25.

Zhang W, Zhu YH, Yang GY, Liu X, Xia B, Hu X, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG affects microbiota and suppresses autophagy in the intestines of pigs challenged with Salmonella Infantis. Front Microbiol. 2018;8:2705.

Abhisingha M, Dumnil J, Pitaksutheepong C. Selection of potential probiotic Lactobacillus with inhibitory activity against Salmonella and fecal coliform bacteria. Probiotics Antimicro Prot. 2018;10:218–27.

Masumizu Y, Zhou B, Kober AH, Islam MA, Iida H, Ikeda-Ohtsubo W, et al. Isolation and immunocharacterization of Lactobacillus salivarius from the intestine of wakame-fed pigs to develop novel “immunosynbiotics”. Microorganisms. 2019;7:167.

Garcia-Castillo V, Komatsu R, Clua P, Indo Y, Takagi M, Salva S, et al. Evaluation of the immunomodulatory activities of the probiotic strain Lactobacillus fermentum UCO-979C. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1376.

Indo Y, Kitahara S, Tomokiyo M, Araki S, Islam MA, Zhou B, et al. Ligilactobacillus salivarius strains isolated from the porcine gut modulate innate immune responses in epithelial cells and improve protection against intestinal viral-bacterial superinfection. Front Immunol. 2021;12:652923.

Sudan S, Zhan X, Li J. A novel probiotic bacillus subtilis strain confers cytoprotection to host pig intestinal epithelial cells during enterotoxic Escherichia coli infection. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10:e01257–e1321.

Baillo A, Villena J, Albarracín L, Tomokiyo M, Elean M, Fukuyama K, et al. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strains modulate intestinal innate immune response and increase resistance to enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection. Microorganisms. 2022;11:63.

Takahashi S, Egawa Y, Simojo N, Tsukahara T, Ushida K. Oral administration of Lactobacillus plantarum strain Lq80 to weaning piglets stimulates the growth of indigenous lactobacilli to modify the lactobacillal population. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2007;53:325–32.

Ko SY, Bae IH, Yee ST, Lee SS, Uuganbayar D, Oh JI, et al. Comparison of the effect of green tea by-product and green tea probiotics on the growth performance, meat quality, and immune response of finishing pigs. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2008;21:1486–94.

Price KL, Totty HR, Lee HB, Utt MD, Fitzner GE, Yoon I, et al. Use of Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation product on growth performance and microbiota of weaned pigs during Salmonella infection. J Anim Sci. 2010;88:3896–908.

Lee JS, Awji EG, Lee SJ, Tassew DD, Park YB, Park KS, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum CJLP243 on the growth performance and cytokine response of weaning pigs challenged with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:3709–17.

Scharek-Tedin L, Pieper R, Vahjen W, Tedin K, Neumann K, Zentek J. Bacillus cereus var. Toyoi modulates the immune reaction and reduces the occurrence of diarrhea in piglets challenged with Salmonella Typhimurium DT104. J Anim Sci. 2013;91:5696–704.

Guerra-Ordaz AA, González-Ortiz G, La Ragione R, Woodward MJ, Collins JW, Pérez JF, et al. Lactulose and Lactobacillus plantarum, a potential complementary synbiotic to control postweaning colibacillosis in piglets. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:4879–86.

Trckova M, Faldyna M, Alexa P, Zajacova ZS, Gopfert E, Kumprechtova D, et al. The effects of live yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae on postweaning diarrhea, immune response, and growth performance in weaned piglets. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:767–74.

Yang KM, Jiang ZY, Zheng CT, Wang L, Yang XF. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum on diarrhea and intestinal barrier function of young piglets challenged with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:1496–503.

Hu Y, Dun Y, Li S, Zhao S, Peng N, Liang Y. Effects of Bacillus subtilis KN-42 on growth performance, diarrhea and faecal bacterial flora of weaned piglets. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2014;27:1131.

Zhao PY, Kim IH. Effect of direct-fed microbial on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, fecal noxious gas emission, fecal microbial flora and diarrhea score in weanling pigs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2015;200:86–92.

Zhou D, Zhu YH, Zhang W, Wang ML, Fan WY, Song D, et al. Oral administration of a select mixture of Bacillus probiotics generates Tr1 cells in weaned F4ab/acR− pigs challenged with an F4+ ETEC/VTEC/EPEC strain. Vet Res. 2015;46:95.

Naqid IA, Owen JP, Maddison BC, Gardner DS, Foster N, Tchórzewska MA, et al. Prebiotic and probiotic agents enhance antibody-based immune responses to Salmonella Typhimurium infection in pigs. Anim Feed Sci and Technol. 2015;201:57–65.

Yang GY, Zhu YH, Zhang W, Zhou D, Zhai CC, Wang JF. Influence of orally fed a select mixture of Bacillus probiotics on intestinal T-cell migration in weaned MUC4 resistant pigs following Escherichia coli challenge. Vet Res. 2016;47:71.

Zhang D, Ji H, Liu H, Wang S, Wang J, Wang Y. Changes in the diversity and composition of gut microbiota of weaned piglets after oral administration of Lactobacillus or an antibiotic. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;100:10081–93.

Arruda PH, Madson DM, Ramirez A, Rowe EW, Songer JG. Bacterial probiotics as an aid in the control of Clostridium difficile disease in neonatal pigs. The Can Vet J. 2016;57:183.

Barba-Vidal E, Castillejos L, Roll VF, Cifuentes-Orjuela G, Moreno Muñoz JA, Martín-Orúe SM. The probiotic combination of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis CECT 7210 and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BPL6 reduces pathogen loads and improves gut health of weaned piglets orally challenged with Salmonella Typhimurium. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1570.

Trevisi P, Latorre R, Priori D, Luise D, Archetti I, Mazzoni M, et al. Effect of feed supplementation with live yeast on the intestinal transcriptome profile of weaning pigs orally challenged with Escherichia coli F4. Animal. 2017;11:33–44.

Liu C, Zhu Q, Chang J, Yin Q, Song A, Li Z, et al. Effects of Lactobacillus casei and Enterococcus faecalis on growth performance, immune function and gut microbiota of suckling piglets. Arch Anim Nutr. 2017;71:120–33.

Hu J, Chen L, Zheng W, Shi M, Liu L, Xie C, et al. Lactobacillus frumenti facilitates intestinal epithelial barrier function maintenance in early-weaned piglets. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:897.

Li Y, Hou S, Chen J, Peng W, Wen W, Chen F, et al. Oral administration of Lactobacillus delbrueckii during the suckling period improves intestinal integrity after weaning in piglets. J Funct Foods. 2019;63:103591.

Zhang W, Wu Q, Zhu Y, Yang G, Yu J, Wang J, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG induces alterations in ileal microbiota with associated CD3-CD19-T-Bet+IFNγ+/- cell subset homeostasis in pigs challenged with Salmonella enterica serovar 4,[5],12:i:-. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:977.

Liu X, Xia B, He T, Li D, Su J-H, Guo L, et al. Oral administration of a select mixture of Lactobacillus and Bacillus alleviates inflammation and maintains mucosal barrier integrity in the ileum of pigs challenged with Salmonella Infantis. Microorganisms. 2019;7:135.

Splichal I, Donovan SM, Splichalova Z, Neuzil Bunesova V, Vlkova E, Jenistova V, et al. Colonization of germ-free piglets with commensal Lactobacillus amylovorus, Lactobacillus mucosae, and probiotic E. coli Nissle 1917 and their interference with Salmonella Typhimurium. Microorganisms. 2019;7:273.

Wang S, Yao B, Gao H, Zang J, Tao S, Zhang S, et al. Combined supplementation of Lactobacillus fermentum and Pediococcus acidilactici promoted growth performance, alleviated inflammation, and modulated intestinal microbiota in weaned pigs. BMC Vet Res. 2019;15:239.

Lépine AF, Konstanti P, Borewicz K, Resink JW, de Wit NJ, Vos PD, et al. Combined dietary supplementation of long chain inulin and Lactobacillus acidophilus W37 supports oral vaccination efficacy against Salmonella Typhimurium in piglets. Sci Rep. 2019;9:18017.

Zhaxi Y, Meng X, Wang W, Wang L, He Z, Zhang X, et al. Duan-Nai-An, A Yeast probiotic, improves intestinal mucosa integrity and immune function in weaned piglets. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4556.

Yang GY, Xia B, Su JH, He T, Liu X, Guo L, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Lactobacillus johnsonii L531 in a pig model of Salmonella Infantis infection involves modulation of CCR6+ T cell responses and ER stress. Vet Res. 2020;51:26.

Sun Z, Li H, Li Y, Qiao J. Lactobacillus salivarius, a potential probiotic to improve the health of LPS-challenged piglet intestine by alleviating inflammation as well as oxidative stress in a dose-dependent manner during weaning transition. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7:547425.

Kwak MJ, Tan PL, Oh JK, Chae KS, Kim J, Kim SH, et al. The effects of multispecies probiotic formulations on growth performance, hepatic metabolism, intestinal integrity and fecal microbiota in growing-finishing pigs. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2021;274:114833.

Wang X, Tian Z, Azad MAK, Zhang W, Blachier F, Wang Z. Dietary supplementation with Bacillus mixture modifies the intestinal ecosystem of weaned piglets in an overall beneficial way. J Appl Microbiol. 2021;130:233–46.

Kang J, Lee JJ, Cho JH, Choe J, Kyoung H, Kim SH, et al. Effects of dietary inactivated probiotics on growth performance and immune responses of weaned pigs. J Anim Sci Technol. 2021;63:520.

Li YS, San Andres JV, Trenhaile-Grannemann MD, van Sambeek DM, Moore KC, Winkel SM, et al. Effects of mannan oligosaccharides and Lactobacillus mucosae on growth performance, immune response, and gut health of weanling pigs challenged with Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharides. J Anim Sci. 2021;99:skab286.

Islam MA, Hashiguchi K, Kober AH, Morie K, Zhou B, Tomokiyo M, et al. Effect of dietary supplementation of immunobiotic Lactiplantibacillus plantarum N14 fermented rakkyo (Allium chinense) pickled juice on the immunocompetence and production performance of pigs. Animals. 2021;11:752.

Zhang Y, Wu T, Chen Z, Meng Y, Zhu Z, Wang Q, et al. Dietary supplementation with Enterococcus faecium R1 attenuates intestinal and liver injury in piglets challenged by lipopolysaccharide. Animals. 2021;11:1424.

Sun T, Miao H, Zhang C, Wang Y, Liu S, Jiao P, et al. Effect of dietary Bacillus coagulans on the performance and intestinal microbiota of weaned piglets. Animal. 2022;16:100561.

Song D, Lee J, Kim K, Oh H, An J, Chang S, et al. Effects of dietary supplementation of Pediococcus pentosaceus strains from kimchi in weaned piglet challenged with Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. J Anim Sci Technol. 2023;65:611.

Cao G, Yang S, Wang H, Zhang R, Wu Y, Liu J, et al. Effects of Bacillus licheniformis on the growth performance, antioxidant capacity, ileal morphology, intestinal short chain fatty acids, and colonic microflora in piglets challenged with lipopolysaccharide. Animals. 2023;13:2172.

Yu X, Dai Z, Cao G, Cui Z, Zhang R, Xu Y, et al. Protective effects of Bacillus licheniformis on growth performance, gut barrier functions, immunity and serum metabolome in lipopolysaccharide-challenged weaned piglets. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1140564.

Gryaznova MV, Dvoretskaya YD, Syromyatnikov MY, Shabunin SV, Parshin PA, Mikhaylov EV, et al. Changes in the microbiome profile in different parts of the intestine in piglets with diarrhea. Animals. 2022;12:320.

Fairbrother JM, Nadeau É, Gyles CL. Escherichia coli in postweaning diarrhea in pigs: an update on bacterial types, pathogenesis, and prevention strategies. Anim Health Res Rev. 2005;6:17–39.

Augustino SM, Ochi EB, Xu Q, Jackson V, Yu Y. Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) and porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) diarrheal infections and resistance in piglets. Arch Environ Cintam Toxicol. 2022;5:136.

Fairbrother JM, Gyles CL. Colibacillosis. In: Zimmerman JJ, Karriker LA, Ramirez A, Schwartz KJ, Stevenson GW, editors. Disease of Swine. 10th ed. 2012. p. 723–47.

Thiagarajah JR, Kamin DS, Acra S, Goldsmith JD, Roland JT, Lencer WI, et al. Advances in evaluation of chronic diarrhea in infants. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:2045–59.

Dubreuil JD, Isaacson RE, Schifferli DM. Animal enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. EcoSal Plus. 2016;7:10–1128.

Kim K, Song M, Liu Y, Ji P. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection of weaned pigs: Intestinal challenges and nutritional intervention to enhance disease resistance. Front Immunol. 2022;13:885253.

Im E, Riegler FM, Pothoulakis C, Rhee SH. Elevated lipopolysaccharide in the colon evokes intestinal inflammation, aggravated in immune modulator-impaired mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G490–7.

Pokharel P, Dhakal S, Dozois CM. The diversity of Escherichia coli pathotypes and vaccination strategies against this versatile bacterial pathogen. Microorganisms. 2023;11:344.

Blanco M, Lazo L, Blanco JE, Dahbi G, Mora A, López C, et al. Serotypes, virulence genes, and PFGE patterns of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli isolated from Cuban pigs with diarrhea. Int Microbiol. 2006;9:53–60.

Lee JB, Kim SK, Yoon JW. Pathophysiology of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli during a host infection. J Vet Sci. 2022;23:e28.

Deng W, Marshall NC, Rowland JL, McCoy JM, Worrall LJ, Santos AS, et al. Assembly, structure, function and regulation of type III secretion systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:323–37.

Jennings E, Thurston TL, Holden DW. Salmonella SPI-2 type III secretion system effectors: molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22:217–31.

Guignot J, Tran Van Nhieu G. Bacterial control of pores induced by the type III secretion system: mind the gap. Front Immunol. 2016;7:84.

Chirullo B, Pesciaroli M, Drumo R, Ruggeri J, Razzuoli E, Pistoia C, et al. Salmonella Typhimurium exploits inflammation to its own advantage in piglets. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:985.

Nyblade C, Parreno V, Zhou P, Hensley C, Oakes V, Mahsoub HM, et al. Establishment of a gnotobiotic pig model of Clostridioides difficile infection and disease. Gut Pathog. 2022;14:22.

Vondruskova HVUVLB, Slamova RVUVLB, Trckova M, Zraly ZVUVLB, Pavlik I. Alternatives to antibiotic growth promoters in prevention of diarrhoea in weaned piglets: a review. Vet Med. 2010;55:199–224.

Wang J, Ji HF, Hou CL, Wang SX, Zhang DY, Liu H, et al. Effects of Lactobacillus johnsonii XS4 supplementation on reproductive performance, gut environment, and blood biochemical and immunological index in lactating sows. Livest Sci. 2014;164:96–101.

Chance JA, DeRouchey JM, Amachawadi RG, Ishengoma V, Nagaraja TG, Goodband RD, et al. Influence of yeast-based pre-and probiotics in lactation and nursery diets on nursery pig performance and antimicrobial resistance of fecal Escherichia coli. J Anim Sci. 2022;100:skac166.

Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Liu F, Mao Y, Zhang Y, Zeng H, et al. Mechanisms and applications of probiotics in prevention and treatment of swine diseases. Porc Health Manag. 2023;9:5.

Hansen LHB, Lauridsen C, Nielsen B, Jørgensen L, Canibe N. Impact of early inoculation of probiotics to suckling piglets on postweaning diarrhoea–a challenge study with enterotoxigenic E. Coli F18. Animal. 2022;16:100667.

Li XQ, Zhu YH, Zhang HF, Yue Y, Cai ZX, Lu QP, et al. Risks associated with high-dose Lactobacillus rhamnosus in an Escherichia coli model of piglet diarrhoea: intestinal microbiota and immune imbalances. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40666.

Azad MAK, Sarker M, Wan D. Immunomodulatory effects of probiotics on cytokine profiles. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018:8063647.

Park S, Lee JW, Jerez Bogota K, Francis D, González-Vega JC, Htoo JK, et al. Growth performance and gut health of Escherichia coli-challenged weaned pigs fed diets supplemented with a Bacillus subtilis direct-fed microbial. Transl Anim Sci. 2020;4:txaa172.

Sperandio B, Fischer N, Sansonetti PJ. Mucosal physical and chemical innate barriers: Lessons from microbial evasion strategies. Semin Immunol. 2015;27:111–8.

McCracken VJ, Lorenz RG. The gastrointestinal ecosystem: A precarious alliance among epithelium, immunity and microbiota. Cell Microbiol. 2001;3:1–11.

Wallaeys C, Garcia-Gonzalez N, Libert C. Paneth cells as the cornerstones of intestinal and organismal health: a primer. EMBO Mol Med. 2023;15:e16427.

Villena J, Kitazawa H. Modulation of intestinal TLR4-inflammatory signaling pathways by probiotic microorganisms: lessons learned from Lactobacillus jensenii TL2937. Front Immunol. 2014;4:512.

Sun D, Bai R, Zhou W, Yao Z, Liu Y, Tang S, et al. Angiogenin maintains gut microbe homeostasis by balancing α-Proteobacteria and Lachnospiraceae. Gut. 2021;70:666–76.

Diefenbach A, Gnafakis S, Shomrat O. Innate lymphoid cell-epithelial cell modules sustain intestinal homeostasis. Immunity. 2020;52:452–63.

Balda MS, Matter K. Tight junctions as regulators of tissue remodelling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2016;42:94–101.

Zong X, Xiao X, Jie F, Cheng Y, Jin M, Yin Y, et al. YTHDF1 promotes NLRP3 translation to induce intestinal epithelial cell inflammatory injury during endotoxic shock. Sci China Life Sci. 2021;64:1988–91.

Guevarra RB, Lee JH, Lee SH, Seok MJ, Kim DW, Kang BN, et al. Piglet gut microbial shifts early in life: causes and effects. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2019;10:1.

Bermudez-Brito M, Plaza-Díaz J, Muñoz-Quezada S, Gómez-Llorente C, Gil A. Probiotic mechanisms of action. Ann Nutr Metab. 2012;61:160–74.

Gāliņa D, Ansonska L, Valdovska A. Effect of probiotics and herbal products on intestinal histomorphological and immunological development in piglets. Vet Med Int. 2020;2020:3461768.

Wang XL, Liu ZY, Li YH, Yang LY, Yin J, He JH, et al. Effects of dietary supplementation of Lactobacillus delbrueckii on gut microbiome and intestinal morphology in weaned piglets. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:692389.

Tegegne BA, Kebede B. Probiotics, their prophylactic and therapeutic applications in human health development: a review of the literature. Heliyon. 2022;8:e09725.

Knaus UG, Hertzberger R, Pircalabioru GG, Yousefi SPM, dos Branco Santos F. Pathogen control at the intestinal mucosa–H2O2 to the rescue. Gut Microbes. 2017;8:67–74.

Yu Q, Yuan L, Deng J, Yang Q. Lactobacillus protects the integrity of intestinal epithelial barrier damaged by pathogenic bacteria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2015;5:26.