Abstract

Background

Methionine or lysine has been reported to influence DNA methylation and fat metabolism, but their combined effects in N6-methyl-adenosine (m6A) RNA methylation remain unclarified. The combined effects of rumen-protected methionine and lysine (RML) in a low-protein (LP) diet on lipid metabolism, m6A RNA methylation, and fatty acid (FA) profiles in the liver and muscle of lambs were investigated. Sixty-three male lambs were divided into three treatment groups, three pens per group and seven lambs per pen. The lambs were fed a 14.5% crude protein (CP) diet (adequate protein [NP]), 12.5% CP diet (LP), and a LP diet plus RML (LP + RML) for 60 d.

Results

The results showed that the addition of RML in a LP diet tended to lower the concentrations of plasma leptin (P = 0.07), triglyceride (P = 0.05), and non-esterified FA (P = 0.08). Feeding a LP diet increased the enzyme activity or mRNA expression of lipogenic enzymes and decreased lipolytic enzymes compared with the NP diet. This effect was reversed by supplementation of RML with a LP diet. The inclusion of RML in a LP diet affected the polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), n-3 PUFA, and n-6 PUFA in the liver but not in the muscle, which might be linked with altered expression of FA desaturase-1 (FADS1) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC). A LP diet supplemented with RML increased (P < 0.05) total m6A levels in the liver and muscle and were accompanied by decreased expression of fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and alkB homologue 5 (ALKBH5). The mRNA expressions of methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) and methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14) in the LP + RML diet group were lower than those in the other two groups. Supplementation of RML with a LP diet affected only liver YTH domain family (YTHDF2) proteins (P < 0.05) and muscle YTHDF3 (P = 0.09), which can be explained by limited m6A-binding proteins that were mediated in mRNA fate.

Conclusions

Our findings showed that the inclusion of RML in a LP diet could alter fat deposition through modulations of lipogenesis and lipolysis in the liver and muscle. These changes in fat metabolism may be associated with the modification of m6A RNA methylation.

Graphical abstract

A systematic graph illustrates the mechanism of dietary methionine and lysine influence on lipid metabolism and M6A. The green arrow with triangular heads indicates as activation and brown-wine arrows with flat heads indicates as suppression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increased price of dietary protein sources and environmental concerns leading to feeding trends towards reduced dietary protein levels to meat-producing animals, including bulls and pigs [1, 2]. Reducing the levels of dietary protein below the NRC recommendation is the most successful nutritional approach in lowering feed cost and nitrogen emissions [3]. However, feeding a low-protein (LP) diet has been shown to affect the carcass characteristics by reducing the carcass lean content and increasing fat accretion depending on the levels of dietary protein reduction and its amino acids composition [2, 4]. It also increased fat deposition by increasing the quantity of energy accessible for fat mass and restricting protein synthesis [5, 6]. One possible explanation could be a deficiency of one or more essential amino acid (EAA). Adding dietary EAA to the LP diet may balance the fat accretion and improve protein synthesis. In this regard, dietary methionine (Met) and lysine (Lys), top-limiting EAA in growing lambs, have been reported to promote protein synthesis and modulate lipid metabolism [7, 8].

A diet containing deficient or adequate Met levels affected lipid turnover by altering the expression of genes-related to fat metabolism in the liver and other tissues [8, 9]. The inclusion of low Met levels in the LP diet has little influence on fat accumulation, but those in a high protein diet reduced fat accretion [5], suggesting that the effects of Met in the LP diet are influenced by other EAAs in the diet. Meanwhile, increasing the levels of dietary Lys has been reported to reduce lipid accretion and improve muscle protein synthesis through regulating key genes involved in various pathways [7]. This effect was connected with improved biosynthesis of L-carnitine, which is reported to decrease carcass fat content and liver total lipids [10, 11]. Conversely, feeding Lys deficient diet increased intramuscular fat content in longissimus dorsi muscle [12]. The findings stated in the above studies point out that dose-dependent influences of dietary Met or Lys in lipid metabolism. However, the combined effects of Met and Lys on the mechanisms of controlling fat removal and accretion and de novo fatty acid synthesis in liver and muscle tissues of lambs under LP diet conditions are not clarified so far. In addition, considering the essence of evaluating N6-methyl-adenosine (m6A) methylation in the liver and muscle and the vital role of liver tissue in lipoprotein and lipid metabolism, the present study focused on the liver and muscle tissues even though the main site of de novo FAs synthesis in sheep is adipose tissue.

Methionine and betaine serve as donors of methyl groups that are involved in the DNA and m6A RNA methylation process. In this content, supplementation of dietary Met affected the DNA methylation process by altering the SAM concentration [13]. Likewise, supplementation of dietary betaine affected the process of m6A RNA methylation [14, 15]. These researches suggested a modulatory role of methyl donors in epigenetic modification. The m6A is considered as the most common form of intrinsic messenger RNA modification in eukaryotic cells [16]. It is a dynamic and reversible process, and installation of a methyl group to m6A is catalyzed by methyltransferases like 3 (METTL3), methyltransferases like 14 (METTL14), and Wilms’ tumor 1-associating protein (WTAP) [17]. Fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) and alkB homologue 5 (ALKBH5) have been identified as demethylase [18, 19], which promote the dumping of a methyl group from m6A via different mechanisms. Subsequently, the YTH domain family (YTHF1–3) proteins have recognized the modification of m6A to influence mRNA maturation, splicing stability, decay, translation, and export [16]. These modifications of RNA could affect several biological functions, such as lipid metabolism and energy homeostasis [20]. Moreover, alters in the m6A RNA methylation and lipid metabolism in various tissues may be inter-related mechanisms in response to supplementation of Met and Lys. Thus, we hypothesized that the inclusion of rumen protected methionine and lysine (RML) in the LP diet may influence lipid metabolism through modulations of m6A RNA methylation in growing lambs. Therefore, the study aimed to investigate m6A RNA methylation, lipid metabolism, and fatty acid profiles in the liver and longissimus dorsi muscle of lambs fed a LP diet supplemented with RML.

Materials and methods

Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Subtropical Agriculture were checked and approved all the experimental protocols used in this trial (202020). Animals were handled in accordance with the protocol approved by the committee. The feeding trial was performed in Hulunbuir city, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China.

Animals, diets, and experimental design

This experimental procedure was in conjunction with our earlier research [21]. Briefly, the rumen-protected lysine (RPL, LysiPEARL) and methionine (RPM, MetiPEARL) products were obtained from Kemin Industries Inc. (Iowa, USA). The RPL and RPM products are contained L-Lys monohydrochloride at 475 g/kg and DL-Met at 500 g/kg, respectively. The rumen passage rates of Lys and Met were about 85% and 66%, respectively, [22]. At four months of age and the initial body weight (BW) of 24.82 ± 2.03 kg, sixty-three fat tail male Hulunbuir lambs were randomly allocated into three dietary groups with three pens per group and seven lambs per pen. The lambs were fed a 14.5% crude protein (CP) diet (positive control, adequate-protein diet [NP]); a 12.5% CP diet (negative control; LP); and a LP diet with RML (LP + RML). The quantity of RPM (0.253 g/kg DM) and RPL (0.50 g/kg DM) supplemented to the lambs were selected following our previous results [23, 24].

The total experimental period was 75 d, including 15 d of acclimatization and 60 d of actual periods. The compositions and nutrient levels of the experimental diets are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Determination of dry matter (DM), ash, and crude protein (CP) of the feed were carried out using the standard protocol of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) [25]. Acid-detergent fiber (ADF) and neutral detergent fiber (NDF) were measured following the methods of Van Soest et al. [26]. The isothermal automatic calorimeter (5E-AC 8018, Changsha Kaiyuan Instruments Co. Ltd., Changsha, China) was used to assay the gross energy (GE) content of feed. Extraction of total amino acids (AA) from the experimental feed was carried out according to the standard procedure descried by the AOAC [27]. The quantification of individual amino acids from the extract was performed using HPLC (Agilent 1100; Agilent Technologies) following the standard protocol of Henderson et al. [28].

Sample collection

Blood was sampled on d 60 (before morning feeding) from the jugular vein of lambs into 5-mL heparinized tubes (Changsha Yiqun Medical Equipment Co., Ltd., Hunan, China) to analyze plasma hormone and lipid-related metabolites. The blood plasma was separated by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 15 min at room temperature and frozen at − 80 °C until analysis. Seven or six lambs per treatment with BW close to the group weight were chosen for slaughter. After evisceration, the weight of the carcass was recorded within 30 min of slaughter. The liver samples were taken quickly, sealed in foil paper, and stored at − 80 °C for later analysis. Then, the longissimus dorsi muscle (muscle) was sampled at the 12/13th rib of each carcass, sealed in foil paper, and stored at − 80 °C until analysis. The dressing percentage was computed as described by Wang et al. [4].

Analysis of plasma metabolite and hormones

The concentrations of plasma triglycerides (TAG), high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), total cholesterol (TC), and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) were analyzed using a Cobas C311 analyzer (Roche Di-agnostics, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) based on the procedure described by Wang et al. [4]. The non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA), leptin (LEP), adiponectin (ADPN), and insulin (INSU) concentrations were assayed using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits specific to sheep following the protocol given by the manufacturer’s manual (Fankel Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) as described by Gebeyew et al. [29]. The results are presented as pg/mL. The sensitivity of the kits was 0.1 pg/mL.

Measurement of tissue enzyme activity, concentration of S-adenosylhomocysteine and L-carnitine

Liver and muscle samples were weighed (100 mg) and homogenized (1:9 w/v) with ice-cold normal saline buffer. Then, the upper liquids were separated by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to detect enzyme activity. Another 100 mg of liver and muscle samples were weighed and homogenized (1:9 w/v) using a mixture of n-butanol, methanol, and deionized water at the ratio of 5:25:70 (v:v:v). Then, the supernatants were retained by centrifugation at 5000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to detect the L-carnitine. The activities of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), malic enzyme (ME), lipoprotein lipase (LPL), carnitine palmitoyltransferase I B (CPT1B), fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4), fatty acid desaturase 1 (FADS1), and stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) were determined in the liver and muscle tissues using the ELISA kits specific to sheep following the recommended procedure (Jiangsu Meimian industrial Co., Ltd., Yancheng, China). The results were presented as pg/mg protein or ng/mg protein. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficient of variation (CV) of all ELISA kits used to detect FGF21, HSL, ACC, LPL, CPT1B, FABP4, FADS1, SCD, and ME were < 10% and < 12%, respectively. The protein concentrations in the liver and muscle tissues were quantified using the BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime Biotech Inc., Shanghai, China). The levels of S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) and L-carnitine were measured using the ELISA kits specific to sheep based on the manufacturers’ protocol (Fankewei Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The results are presented as ng/g or pg/g [30]. The intra-assay and inter-assay CV of ELISA kits used to SAH and L-Carnitine were < 8% and < 10%, respectively.

Fatty acid profiling

The liver and muscle tissue samples were freeze-dried. Then, the total lipids from lyophilized samples were extracted using the chloroform-methanol (2:1, v/v) following the methods described elsewhere [31]. Fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) of the tissues and experimental diets were prepared using a solution of KOH-methanol as reported by Tan et al. [32] . The FAME was identified by an Agilent 7890A gas chromatographer (GC) system equipped with a flame ionization detector (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) as previously described by Wang et al. [4]. The concentration of each fatty acids was quantified by comparing the retention times of the peak area with those authentic standards (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), and presented as a percentage of total fatty acids. The partial sums of saturated fatty acids (SFA), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), n-3 PUFA, and n-6 PUFA were computed.

RNA extraction and gene expression profiling

Cytoplasmic RNA was isolated from liver and muscle tissues of lambs using the cytoplasmic and nuclear RNA purification kit following the kit procedures (Norgen Biotek Corp., Thorold, ON, Canada). The concentration and purity of the extracted RNA were checked using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The integrity of total RNA was verified by agarose-formaldehyde (1%) gel electrophoresis. Aliquots of RNA samples were reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using Evo M-MLV Reverse Transcription Kit (AG11707, Accurate Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Changsha, Hunan, China) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Then, the synthesized cDNA was placed at − 20 °C until analysis.

The lipid metabolism-related genes investigated in this study were ACC, SCD, HSL, LPL, CPT1B, FABP4, FGF21, adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), fatty acid synthase (FASN), sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBF1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPARα) (Additional file 1: Table S1). As internal reference genes, expression of ribosomal protein S9 (RPS9), β-actin, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were analyzed. The stability of the reference genes were assessed using BestKeeper, Genorm, and NormFinder tools [33]. The RPS9 and GAPDH were identified as the most stable reference gene across experimental treatment. Therefore, the two reference genes were used to normalize the data. The amplification efficiency of all primers used in this study was computed using serial cDNA dilution curves. All primers showed efficiency between 90% and 110%, and correlation coefficients were close to 1.0. All gene-specific primers sequences used in the present study were synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The real-time PCR was performed using SYBR® Green Premix Pro Taq HS qPCR Kit (AG11707, Accurate Biology Co., Ltd., Changsha, China) on a fluorescence LightCycler 480 II system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) following the manufacturer’s direction. The details of the reaction program were described elsewhere [34]. The relative mRNA expressions of the target genes were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method [35].

Quantification of m6A content

The m6A RNA methylation quantification kit (Epigentek Group Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA) was used to detect the total content of m6A in liver and muscle tissues according to the protocol given by the manufacturer’s manual. The total content of m6A was computed using the formula: m6A % = {[(ODSample – ODNC)/S] ÷ [(ODPC – ODNC)]} × 100%, and S, NC, and PC denote the total quantity of input RNA, negative control and positive control, respectively, as described by Heng et al. [17].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were executed using origin pro 2020b and the SPSS version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). First, Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests were employed to confirm the normality and homoscedasticity of data, respectively. Then, Tukey’s post hoc tests were used to determine the differences between treatment means, significant difference was regards as P < 0.05 and trends were recognized 0.05 ≤ P < 0.1. The data are presented as the means ± standard errors of the mean (SEMs). The correlations between genes-related to lipid metabolism and methylation were performed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient in R package and the network was constructed on the Omics-studio (LC-Bio Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China).

Results

Carcass parameter, lipid-related metabolites, and hormones

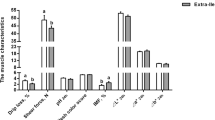

The live body weight, average daily gain and feed intake, G:F ratio, dressing percentage, and hot carcass weight were similar (P > 0.05) among the three dietary groups (Table 3). The concentrations of plasma TAG and NEFA tended to be increased in the LP diet group than the other two groups (P < 0.1, Fig. 1). The concentration of plasma LEP (P = 0.07) in the LP + RML diet group tended to be lower than that in the LP diet group. In comparison to the other two groups, the concentrations of L-carnitine in the liver and muscle were enhanced (P < 0.05) in the RML supplemented group (Fig. 2).

Effect of a low-protein diet supplemented with rumen-protected methionine and lysine on lipid-related metabolites and hormone levels. Values are expressed as means ± SEM indicated by vertical bars. Different letters indicate a significant difference among three dietary treatments (P < 0.05). NP, adequate protein diet; LP, low-protein diet; LP + RML, low-protein diet supplemented with rumen-protected methionine and lysine

Effect of a low-protein diet supplemented with rumen-protected methionine and lysine on L-carnitine levels in liver and muscle. On each side of the gray line is a kernel density estimation to illustrate the distribution of shape of the data in a group. Wider and skinnier sections of the violin plot represent a higher and lower probability. The white dot represents the mean and the thick red bar in the center represents the interquartile range. * = significantly different means (P < 0.05). NP, adequate protein diet (n = 7); LP, low-protein diet (n = 6); LP + RML, low-protein diet supplemented with rumen-protected methionine and lysine (n = 7)

Fatty acids profiles in liver and muscle tissues

The compositions of FA in the liver and muscle tissues are presented in Tables 4 and 5. In liver, the C16:0 concentration was greater (P < 0.05) in the LP diet group than that in the NP diet group, but comparable with the RML supplemented group. The concentration of C16:1 was greater (P < 0.05) in the LP and LP + RML diet groups than that in the NP diet group. In comparison to the NP diet group, the concentration of C18:2n-6c was reduced in the LP diet group but equivalent to the LP + RML diet group. The LP diet group had a higher (P < 0.05) concentration of C18:1n-9 t than those in the other two groups. In comparison to the NP diet group, the LP and LP + RML diet groups had lower (P < 0.05) concentrations of C18:3n-3, C20:3n-6, n-3 and n-6 PUFA. The LP diet group had greater (P < 0.05) SFA and lower (P < 0.05) PUFA and n-6 PUFA than that in the NP diet group but were equivalent to the RML supplemented group. However, neither a LP diet nor LP + RML affected (P > 0.05) the partial sums of MUFA in the liver. In muscle, the concentrations of C15:0 and C18:3n-3 in the LP and LP + RML diet groups were reduced (P < 0.05) than that of the NP diet group. In addition, the n-3 PUFA concentration tended to be reduced (P = 0.07) in the LP and LP + RML diet groups. Conversely, the LP diet increased (P < 0.05) the concentrations of C18:1n-9 t and C20:4n-6 than that of the other two diets. The partial sums of SFA, PUFA, and n-6 PUFA in the muscle were unaffected (P > 0.05) by dietary groups.

Enzyme activity in the liver and muscle tissues

As depicted in Table 6, adding RML in a LP diet depressed (P < 0.05) ACC, ME, and SCD enzyme activities in the liver compared with the LP diet. However, those enzyme activities were unaffected in muscle (P > 0.05) by the supplementation of RML with a LP diet except for SCD (Table 7). In liver and muscle, the CPT1B enzyme activity in the LP + RML diet group was higher (P < 0.05) than that in the other two diet groups. In comparison with the LP diet group, the LP + RML diet group increased (P < 0.05) the activity of HSL only in the liver. The LP diet increased (P < 0.05) the enzyme activities of FABP4 and LPL in the liver and muscle compared with the NP and LP + RML diets. Meanwhile, the LP diet increased (P < 0.05) the FADS1 and FGF-21 enzyme activities only in the liver. However, no variations were found between dietary groups for FADS1, FGF21, and HSL enzyme activities in the muscle (P > 0.05).

Lipid metabolism related genes in the liver and muscle tissues

In the liver, the mRNA expressions of ACC, SCD, LPL, FABP4, and SREBF1 were greater (P < 0.05) in the LP diet group than those in the other two groups (Fig. 3). Meanwhile, the expression of FADS1 (P < 0.05) was down-regulated in the LP + RML diet group compared with the other two groups (Fig. 3A). Conversely, the expression of CPT1B tended to be enhanced (P = 0.06) in the LP + RML diet group than those in the other two groups (Fig. 3B). In comparison to the NP diet group, the mRNA expression of FGF21 was up-regulated (P < 0.05) in the LP and LP + RML diet groups. The mRNA expressions of HSL and PPARα were up-regulated (P < 0.05) by the supplementation of RML with a LP diet, while mRNA expression of PPARγ in the LP + RML diet group was similar (P > 0.05) with the other two groups (Fig. 3C). However, the mRNA expressions of liver FASN and ATGL were unaffected (P > 0.05) by dietary treatments. In muscle, the mRNA expressions of SCD, LPL, FABP4, and PPARγ were up-regulated (P < 0.05) in the LP diet group than those in the other two groups (Fig. 3D-F). In addition, the mRNA expression of FASN tended to be up-regulated (P = 0.051) in the LP diet group than that of in the NP diet group. Furthermore, the mRNA expressions of CPT1B, ATGL, and PPARα were elevated (P < 0.05) in the LP + RML diet group than those in the other two dietary groups. However, the mRNA expressions of ACC, FADS1, HSL, SREBF1, and FGF21 in the muscle were similar (P > 0.05) among the three dietary groups.

Effect of a low-protein diet supplemented with rumen-protected methionine and lysine on the expression of genes involved in fat metabolism in the liver (A, B, C) and muscle (D, E, F). Data are expressed as means ± SEM indicated by vertical bars. Different letters indicate a significant difference among the three dietary treatments (P < 0.05). NP, adequate protein diet (n = 7); LP, low-protein diet (n = 6); LP + RML, low-protein diet supplemented with rumen-protected methionine and lysine (n = 7)

The m6A RNA methylation and its related gene expression in liver and muscle tissues

The total content of m6A and SAH and relative mRNA expressions were performed to reveal the impacts of an LP diet supplemented with and without RML on the mechanism of regulating m6A RNA methylation in the liver and muscle tissues. The addition of RML in a LP diet improved (P < 0.05) the total content of m6A and SAH in the liver and muscle (Fig. 4). In liver, a LP diet supplemented with RML down-regulated (P < 0.05) the mRNA expression levels of METTL3/14, ALKBH5, FTO, and YTHDF2 (Fig. 5A-C). Likewise, mRNA expression levels of METTL3/14, WTAP, FTO, and ALKBH5 in the muscle were down-regulated (P < 0.05) by the supplementation of RML with a LP diet (Fig. 5D-F). In addition, the mRNA expression levels of WTAP (P = 0.06) in the liver and YTHD3 (P = 0.09) in the muscle tended to be depleted in the LP + RML diet group, whereas the gene expressions of muscle WTAP, YTHDF1 and YTHDF2 were similar (P > 0.05) among the three groups.

Effect of a low-protein diet supplemented with rumen-protected methionine and lysine on the m6A RNA methylation and SAH levels in liver and muscle. On each side of the gray line is a kernel density estimation to illustrate the distribution of shape of the data in a group. Wider and skinnier sections of the violin plot represent a higher and lower probability. The white dot represents the mean and the thick red bar in the center represents the interquartile range. * = significantly different means (P < 0.05). NP, adequate protein diet (n = 7); LP, low-protein diet (n = 6); LP + RML, low-protein diet supplemented with rumen-protected methionine and lysine (n = 7)

Effect of a low-protein diet supplemented with rumen-protected methionine and lysine on the expression of genes related to m6A RNA methylation in liver (A, B, C) and muscle (D, E, F). Data are expressed as means ± SEM indicated by vertical bars. Different letters indicate a significant difference among the three dietary treatments (P < 0.05). NP: adequate protein diet (n = 7), LP: low-protein diet (n = 6), LP + RML: low-protein diet supplemented with rumen-protected methionine and lysine (n = 7)

Correlations among genes-associated to m6A RNA methylation and lipid metabolism in the liver and muscle

In liver, the mRNA expressions of ALKBH5 and YTHDF2 had a negative correlation (P < 0.05) with HSL and PPARα (Fig. 6A). The mRNA expressions of METTL3 and METTL14 were positively correlated (P < 0.05) with ACC, FADS1, SREBF1, SCD, and LPL and negatively correlated (P < 0.05) with PPARα. Likewise, WTAP and FTO showed a positive association (P < 0.05) with FGF21 and PPARγ. In muscle, YTHDF3 expression was positively correlated (P < 0.05) with LPL, FABP4, and FASN (Fig. 6B). Meanwhile, the mRNA expressions of METTL3 and METTL14 had a negative association with CPT1B and PPARα (P < 0.05) and a positive association with FABP4 (P < 0.01) and LPL (P < 0.05). Likewise, FTO and ALKBH5 were negatively correlated (P < 0.01) with CPT1B and PPARα and positively correlated (P < 0.01) with FABP4, LPL, and PPARγ.

Discussion

Following ruminal biohydrogenation, dietary FAs are likely to be further metabolized in the liver and other tissue involved in FAs metabolism despite adipose tissue is a main site of de novo FAs synthesis in sheep [36, 37]. This process could affecting the FAs deposition in the respective tissue. Higher FAs composition in the liver than muscle tissue are not uncommon, and likely reflect the discrepancy of tissues in metabolic roles. In the present study, distinct gene expression and enzyme activity patterns in responses to feeding a LP diet or LP + RML were observed in the liver and muscle tissues. It unveils tissue-specific regulation systems between the inductions of key transcription factor, followed by the activity of genes related to lipogenesis and FAs oxidation. The greater FAs modification in the liver can be accompanied by the greater alters in the expression of SREBF1, ACC, FGF21, and FADS1 genes responsible for lipogenesis in this tissue. This discrepancy might be attributed to the slight difference in the FAs profiles between the two tissues. In this context, the concentration of C16:0 (palmitic) in the liver of lambs fed a LP diet was increased, which is in line with the greater concentration of plasma TAG and mRNA expression levels of ACC, as palmitic is one of the final products of de novo synthesis of SFA. These showed that feeding a LP diet increased the concentration of C16:0 as a result of increased enzymes involved in de novo FA synthesis, thereby increasing the concentration of plasma TAG. In agreement with the present findings, linear patterns between expression of level ACC and concentrations of C12:0, C14:0, and C16:0 were reported in cattle under different feeding regimes [38]. In addition, the increased concentration of C16:0 in the liver may be partly due to the high content of C16:0 in the LP and LP + RML groups, which was nearly 5% more than that of the NP diet. Compared with the NP diet group, the relative content of C16:0 in the liver of LP and LP + RML groups was more than 9% and 4%, respectively, which indicates that the addition of RML had an effect on the liver fatty acids synthesis. The observed changed concentration of C15:0 in the present study was likely a result of altered rumen microbial profiles and propionic acid production, which can influence de novo FA synthesis [39].

Feeding a LP diet improved the concentration of C18:1n-9 t in the liver and muscle of the present study and was revered by the supplementation RML with a LP diet, which may be explained by the same expression pattern of SCD mRNA. However, the C18:1n-9c concentration did not confirm this pattern. Because the inclusion of RML in the LP diet inhibited the expression of SCD mRNA, which plays a significant role in converting C18:0 into C18:1c-9, the concentration of C18:1n-9c did not decrease in this group. Perhaps, there may be additional genes that regulate the conversion of C18:0 to C18:1n-9c. Nevertheless, the increase or decrease in SCD activity or expression is not always accompanied by an altering C18:1n-9c or total MUFA concentration. In this context, feeding a LP diet increased the concentration of C18:1n-9 in the adipose tissue without affecting the protein expression of SCD [40], suggesting that the concentration of C18:1n-9 increased independent of SCD expression in the adipose tissue. Conversely, the inclusion of linseed in a corn-silage-grass hay diet of bulls decreased the mRNA expression of SCD in the adipose tissue without affecting the concentration of single C18:1n-9 and total MUFA [41]. The authors stated that feeding a linseed affected the concentration of C18:1n-7 (cis-vaccenic acid). Considering the role of SCD gene in the synthesis of conjugated linoleic acid (C18:1c-9 t11) from vaccenic acid (C18:1 t-11) and other single MUFA [42, 43], the increased SCD expression in lambs fed a LP diet can also be explained by altering the concentration of other MUFA such as C16:1 and C18:1n-9 t. In addition, a positive association between the expression of SCD and concentrations of 14:1, 16:1, and 18:1n-9 were also reported elsewhere [44, 45].

As of C18:2n-6 is the precursor of the n-6 long-chain PUFA series built via extension and desaturation of omega-3/6 FAs [46]. The observed lower concentration of C18:2n-6 and C18:3n-3 in the liver of lambs fed with a LP, or LP + RML diet could be explainable by the relative lower intakes of C-18 unsaturated FA from soybean meal and its ruminal biohydrogenation. Decreased concentrations of PUFA 18:2 and 18:3 in the milk fat were also found in the cows fed a diet containing a reduced level of C-18 unsaturated FA [47]. In addition, the lower concentrations of single PUFA in the liver of lambs fed the LP + RML diet could be partly accompanied by the decreased expression level of FADS1 in the present study, which is a rate-limiting enzyme in de novo PUFA synthesis [48]. However, the single PUFA in the liver of LP did not confirm this pattern. Other members of the FADS gene family, such as FADS2, may be responsible for regulating the synthesis of single PUFA under LP diet conditions. In the present study, the FAs results showed increased concentrations of single SFA and total SFA and decreased total PUFA proportions in the liver, but not in the muscle of lambs fed the LP diet. In concordance with the present results, feeding a LP diet did not affect the single or partial sums of SFA and total SFA and PUFA in the muscle of yearling lamb [49]. The results indicated that reducing dietary protein levels by 2% does not have pronounced effects on the partial sums of SFA, MUFA, and PUFA in the muscle of lambs. However, a significant shift in the FA composition of pigs fed LP diets was reported elsewhere [50], which could be explained by breed differences.

To further confirm whether a LP diet supplemented with or without RML alters the lipid metabolism, we assessed the activity or expressions of the lipogenic and lipolytic enzymes. The malonyl-CoA, believed to be a rate-limiting enzyme in the process of FAs synthesis, is synthesized from acetyl CoA by the enzyme ACC [51]. Then, the synthesized malonyl-CoA is converted into FAs in the presence of FAS enzyme and NADPH as hydride donor [52]. The SCD is a vital and rate-limiting enzyme involved in MUFA synthesis from SFA by lodging a double bond between two carbons of the fatty acyl chain [43]. Supplementation of RML with a LP diet down-regulated the expression of lipogenesis ACC, SCD, and FADS1 mRNA in the liver but not in the muscle, suggesting that the inclusion of RML in a LP diet depress lipogenic genes involved in the de novo FAs synthesis via activating transcription factor SREBF1. It could also be explainable that supplementation of RML with a LP diet decreased the plasm TAG concentration by regulating genes involved in FAs synthesis.

The SREBF1 is a key transcriptional factor that regulates genes implicated in the de novo synthesis of FAs and TAG and maintains cellular lipid homeostasis [53]. The lack of changes in the expression of ACC, FADS1, and FGF21 in the muscle of the present study are consistent with the expression of SREBF1, which may preferentially regulate or activate those genes for the de novo lipogenesis. It could also be explainable by the limited role of ACC, FADS1, and FGF21 genes in the lipogenesis-associated pathways of muscle under the present experimental condition. These results were agreed with the previous findings that showed the expression of lipogenic enzymes in the muscle was lower than in liver or adipose tissues of lambs and cattle under different feeding regimes [39, 48]. The transcription factor SREBF1 has also been shown to mediate the expression of FGF21 in the hepatocytes [54], which influences lipid accretion and mitochondrial oxidative capacity of the fat cells. Xu et al. [55] have confirmed using goat intramuscular preadipocyte that FGF21 could be negatively regulated by SREBP1 during adipogenic differentiation. Higher mRNA expression of FGF21 has been observed in the liver of mice fed a LP diet [56]. In the present study, the supplementation of LP diet increased the expression of liver FGF21, accompanied by increased expression of SREBF1, reinforcing the involvement of FGF21 in the lipid metabolism in the liver of lamb under LP protein diet conditions. However, this change was not observed in the muscle of lambs, suggesting that it is mainly produced in the liver than muscle.

The FABP4 is a carrier protein responsible for the carting of free FAs, released from extra-or-intracellular hydrolysis of TAG in the presence of ATGL and HSL, into the specific fat cells. After that, acyl-CoA is carted into mitochondria for β-oxidation following its production from free FAs [57]. Supplementation of RML with a LP diet increased the activity of HSL or ATGL and decreased the expression of FAPB4 in the liver and muscle of the present study. It would be explainable that the HSL or ATGL could undergo the hydrolysis of intracellular TAG to release free FAs, thereby transported by FAPB4 into the fat cell, which contributes to the alteration of fat deposition. The LPL is believed to be responsible for the hydrolysis of extracellular TAG in lipoproteins or TAG-rich lipoproteins and regulates TAG portioning between storage in adipose tissues and oxidation in muscle, thereby supplying appropriate FAs as fuel for muscle growth [58]. The inclusion of RML in a LP diet down-regulated the expression of LPL in the liver and muscle of the present study, suggesting that the availability of FAs as an energy source for the respective tissue was reduced. Another significant finding of the present study is that increased mRNA expression of PPARα in the liver and muscle of lambs fed a diet consisting of RML, suggesting that the inclusion of RML in a LP diet promotes FAs oxidation via activating PPARα. The PPARα is a major transcriptional activator or sensor of FA oxidation and plays a crucial role in this process, whereby the synthesis of fatty acids is influenced [59]. Elevated mRNA expression of CPT1B in both tissues of the present study was accompanied by an increased expression of PPARα or concentration of endogenous carnitine. Perhaps, dietary Lys and Met, an exogenous precursor for L-carnitine biosynthesis, could increase the expression of CPT1B that regulated FAs catabolism through either translocating the FA into mitochondria or regulating the enrollment of FAs flux into the β-oxidation pathway [60]. Thus, this study clearly showed that the inclusion of RML in a LP diet could promote lipolysis by regulating the transcriptional factors and downstream genes, which eventually led to low-fat accretion in the respective tissues of lambs.

Studies have been shown the role of m6A RNA methylation in regulating fat metabolism in lambs [61] and pigs [17]. Lipid accretions are inversely regulated by m6A RNA methylation in pigs [17, 62]. A recent study has shown that methyl donors, such as betaine, can regulate the m6A RNA methylation in HepG2 cells [15]. Considering Met and Lys regulate methylation and Met as a methyl donor, we measured the total m6A methylation level and the mRNA expressions of methylases and demethylases enzymes to assess the impacts of a LP diet supplemented with and without RML on m6A RNA modification. The results showed that supplementation of RML with a LP diet increased the m6A RNA methylation in the liver and muscle. The increased m6A RNA methylation was accompanied by the increased concentrations of SAM, which is the main methyl donor synthesized from Met through one-carbon metabolism [13].

Furthermore, the observed decreased expressions of FTO and ALKBH5 enzymes in the present study of liver and muscle were accompanied by increased the relative m6A levels in the RML supplemented group or decreased expression of transcription factor PPARγ. These results reinforced the inverse association of FTO and m6A [14, 62] or showed the influences of FTO in fat metabolism partly through regulating the expression levels of PPARγ [63]. In this regard, supplementation of betaine to mice reversed high-fat diet-induced hepatic lipid accretion via down-regulated expression of FTO, thereby increasing the level of m6A [14]. Wang et al. [62] showed using a methyl donor (betaine) and methylation inhibitor (cycloleucine) that levels of m6A could regulate the lipid accretion via FTO in porcine adipocytes, showing that FTO-dependent removal of m6A has a vital role to regulate fat deposition. In addition, a mechanistic influence of FTO on the expression of PPARγ during preadipocyte differentiation was reported [63, 64]. These researches indicated that m6A could regulate fat deposition directly through FTO or indirectly through PPARγ. In the present study, the inclusion of RML in a LP diet increased the m6A status via decreased expression of FTO, and the decreased mRNA expression of FTO was consistent with that of PPARγ in both tissues, suggesting that m6A could involve in lipid metabolism by controlling the expression of FTO and (or) PPARγ in lambs. These results were further supported by the correlation analysis that showed a positive association between mRNA expressions of FTO and PPARγ in both tissues.

It has also been documented that m6A methylation is positively and negatively associated with methyltransferase METTL3 and demethylase FTO in porcine adipocytes, respectively [62]. A positive association between m6A and methyltransferase has been observed in lambs exposed to heat stress [61]. However, the positive association between m6A and methyltransferase was not observed in the liver and muscle of the present study. The possible reason might be explained by the increased concentration of SAH, which is reported to have strong inhibitory effects on the activity of METTL3 [65]. In addition, the mRNA or protein expression levels of METTL and WTAP partly failed to show a positive correlation with m6A RNA methylation in the liver and adipose tissue of pigs fed different level of branched-chain AAs [17]. It would also be explained that other m6A writers could be responsible for the m6A deposition process, which needs further investigation. Recently, several m6A writers, including METTL16 and PCIFI, have been identified, which could be a potential regulators [66, 67].

Growing evidence showed that the YTHDF1–3, m6A-binding proteins, are obliged to recognize the m6A modification and promote various downstream effects [16]. The YTHDF1 has been found to control the expression of mitochondrial carrier 2 protein and trigger mRNA translation [68], while YTHDF2 relates to admitting m6A-modified mRNA and influences its stability [69]. In this study, supplementation of RML with a LP diet down-regulated the expressions of liver YTHDF2 and muscle YTHDF3, suggesting that limited m6A-binding proteins recruited the m6A-modified mRNA. Other m6A reader proteins that might be involved in the RML-induced prevention of lipid accretion can explain the lack of changes in m6A-binding proteins. Overall, the current study highlighted that dietary Met and Lys influenced m6A RNA methylation, methyltransferase, and demethylase enzymes, and were more pronounced in the liver than the muscle. The increased m6A RNA methylation and decreased expressions of FTO and transcription factor PPARγ in this study reinforced the potential role of RML in modulating lipid metabolism through modification of m6A RNA methylation.

Conclusions

Our results indicated that feeding a low-protein diet increased lipogenic enzymes and decreased lipolytic enzymes in the liver and muscle compared with a NP diet, which was reversed by the inclusion of methionine and lysine supplementation in a LP diet. The composition of fatty acids was more affected in the liver than in the muscle, which may be linked with higher mRNA expression of the vital lipogenic enzymes and adipogenic transcription factors. Dietary methionine and lysine in a low-protein diet could influence lipid metabolism via m6A RNA methylation, as evidenced by the decreased demethylases of ALKBH5 and FTO, which may regulate lipid accretion through PPARγ.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LP:

-

Low-protein

- NP:

-

Adequate protein

- RML:

-

Rumen-protected methionine and lysine

- LBW:

-

Live body weight, kg

- ADG:

-

Average daily gain

- ADFI:

-

Average daily feed intake

- HCW:

-

Hot carcass weight

- DP:

-

Dressing percentage

- m6A:

-

N6-methyl-adenosin

- FAs:

-

Fatty acids profiles

- SFA:

-

Saturated fatty acids

- MUFA:

-

Monounsaturated fatty acids

- PUFA:

-

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- FAME:

-

Fatty acid methyl esters

- FADS1:

-

Fatty acdis desaturase-1

- ACC:

-

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- FTO:

-

Fat mass and obesity-associated protein

- ALKBH5:

-

AlkB homologue 5

- METTL3:

-

Methyltransferase-like 3

- METTL14:

-

Methyltransferase-like 14

- YTHDF1–3:

-

YTH domain family proteins 1–3

- TAG:

-

Triglycerides

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- NEFA:

-

Non-esterified fatty acid

- LEP:

-

Leptin

- ADPN:

-

Adiponectin

- INSU:

-

Insulin

- FGF21:

-

Fibroblast growth factor 21

- HSL:

-

Hormone-sensitive lipase

- ME:

-

Malic enzyme

- LPL:

-

Lipoprotein lipase

- CPT1B:

-

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I B

- FABP4:

-

Fatty acid binding protein 4

- FADS1:

-

Fatty acid desaturase 1

- SCD:

-

Stearoyl-CoA desaturase

- SAH:

-

S-adenosylhomocysteine

- ATGL:

-

Adipose triglyceride lipase

- FASN:

-

Fatty acid synthase

- SREBF-1:

-

Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1

- PPARγ:

-

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ

- PPARα:

-

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α

- GAPDH:

-

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- RPS9:

-

Ribosomal protein S9

References

Cortese M, Segato S, Andrighetto I, Ughelini N, Chinello M, Schiavon E, et al. The effects of decreasing dietary crude protein on the growth performance, feed efficiency and meat quality of finishing charolais bulls. Animals. 2019;9(11):906. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9110906.

Li Y, Li F, Chen S, Duan Y, Guo Q, Wang W, et al. Protein-restricted diet regulates lipid and energy metabolism in skeletal muscle of growing pigs. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64(49):9412–20. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.6b03959.

Zhu W, Xu W, Wei C, Zhang Z, Jiang C, Chen X. Effects of decreasing dietary crude protein level on growth performance, nutrient digestion, serum metabolites, and nitrogen utilization in growing goat kids (Capra hircus). Animals. 2020;10(1):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10010151.

Wang Y, Wang Q, Dai C, Li J, Huang P, Li Y, et al. Effect of dietary protein level on growth, carcass characteristics, serum biochemical index, and meat quality of Hu male lambs. Small Rumin Res. 2021;194:106294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2020.106294.

Chaumontet C, Azzout-Marniche D, Blais A, Piedcoq J, Tomé D, Gaudichon C, et al. Low-protein and methionine, high-starch diets increase energy intake and expenditure, increase FGF21, decrease IGF-1, and have little effect on adiposity in mice. Am J Phys Regul Integr Comp Phys. 2019;316(5):R486–R501. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00316.2018.

Dannenberger D, Nuernberg K, Nuernberg G, Priepke A. Impact of dietary protein level and source of polyunsaturated fatty acids on lipid metabolism-related protein expression and fatty acid concentrations in porcine tissues. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(51):12453–61. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf504699a.

Wang T, Feugang JM, Crenshaw MA, Regmi N, Blanton JR, Liao SF. A Systems biology approach using transcriptomic data reveals genes and pathways in porcine skeletal muscle affected by dietary lysine. Int J Mol Med Sci. 2017;18(4):885. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18040885.

Aissa AF, Tryndyak V, de Conti A, Melnyk S, Gomes TD, Bianchi ML, et al. Effect of methionine-deficient and methionine-supplemented diets on the hepatic one-carbon and lipid metabolism in mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2014;58(7):1502–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201300726.

Castellano R, Perruchot MH, Conde-Aguilera JA, van Milgen J, Collin A, Tesseraud S, et al. A methionine deficient diet enhances adipose tissue lipid metabolism and alters anti-oxidant pathways in young growing pigs. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0130514. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130514.

Hajilou M, Dehghan-Banadaky M, Zali A, Rezayazdi K. The effects of dietary L-carnitine and rumen-protected choline on growth performance, carcass characteristics and blood and rumen metabolites of Holstein young bulls. J Appl Anim Res. 2014;42(1):89–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/09712119.2013.822807.

Carlson DB, McFadden JW, D'Angelo A, Woodworth JC, Drackley JK. Dietary L-carnitine affects periparturient nutrient metabolism and lactation in multiparous cows. J Dairy Sci. 2007;90(7):3422–41. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2006-811.

Katsumata M, Kyoya T, Ishida A, Ohtsuka M, Nakashima K. Dose-dependent response of intramuscular fat accumulation in longissimus dorsi muscle of finishing pigs to dietary lysine levels. Livest Sci. 2012;149(1):41–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2012.06.025.

Miousse IR, Pathak R, Garg S, Skinner CM, Melnyk S, Pavliv O, et al. Short-term dietary methionine supplementation affects one-carbon metabolism and DNA methylation in the mouse gut and leads to altered microbiome profiles, barrier function, gene expression and histomorphology. Genes Nutr. 2017;12(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12263-017-0576-0.

Chen J, Zhou X, Wu W, Wang X, Wang Y. FTO-dependent function of N6-methyladenosine is involved in the hepatoprotective effects of betaine on adolescent mice. J Physiol Biochem. 2015;71(3):405–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13105-015-0420-1.

Zhang L, Qi Y, AL Z, Liu S, Zhang Z, Zhou L. Betaine increases mitochondrial content and improves hepatic lipid metabolism. Food Funct. 2019;10(1):216–23. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8fo02004c.

Zhao Y, Chen Y, Jin M, Wang J. The crosstalk between m(6)a RNA methylation and other epigenetic regulators: a novel perspective in epigenetic remodeling. Theranostics. 2021;11(9):4549–66. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.54967.

Heng J, Wu Z, Tian M, Chen J, Song H, Chen F, et al. Excessive BCAA regulates fat metabolism partially through the modification of m(6)a RNA methylation in weanling piglets. Nutr metab. 2020;17:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-019-0424-x.

Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, Dai Q, Zheng G, Yang Y, et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(12):885–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.687.

Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49(1):18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015.

Huang T, Guo J, Lv Y, Zheng Y, Feng T, Gao Q, et al. Meclofenamic acid represses spermatogonial proliferation through modulating m6A RNA modification. J Animal Sci Biotechnol. 2019;10:63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-019-0361-6.

Gebeyew K, Yang C, He Z, Tan Z. Low-protein diets supplemented with methionine and lysine alter the gut microbiota composition and improve the immune status of growing lambs. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;105(21–22):8393–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-021-11620-4.

Lee C, Lobos NE, Weiss WP. Effects of supplementing rumen-protected lysine and methionine during prepartum and postpartum periods on performance of dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2019;102(12):11026–39. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2019-17125.

Sun ZH, Tan ZL, Liu SM, Tayo GO, Lin B, Teng B, et al. Effects of dietary methionine and lysine sources on nutrient digestion, nitrogen utilization, and duodenal amino acid flow in growing goats. J Anim Sci. 2007;85(12):3340–7. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2006-718.

Zhu X, Jiao J, Zhou C, Tang S, Wang M, Kang J, et al. Effects of dietary methionine and lysine supplementation on nutrients digestion, serum parameters and mRNA expression of related amino acid sensing and transporting genes in growing goats. Small Rumin Res. 2018;166:1–6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10010151.

Lee MH. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International (16th edn): edited by Patricia A. Cunniff, AOAC International. Trends Food Sci Technol. 1995;6(11):382. https://doi.org/10.1016/0924-2244(95)90022-5.

Van Soest PJ, Robertson JB, Lewis BA. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74:3583–97. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2.

AOAC. Official methods of analysis. In: Horwitz W, editor. vol. 17. 17th ed. Gaithersburg: The association of official analytical chemists; 2000. p. 1–2.

Henderson JW, Ricker RD, Bidlingmeyer BA, Woodward C. Rapid, accurate, sensitive, and reproducible HPLC analysis of amino acids. Agilent Technologies, Application Note, vol. 1100; 2000. p. 1–10. Publication No:5980–1193

Gebeyew K, Chen W, Yan Q, He Z, Tan Z. Growth of pancreas and intestinal enzyme activities in growing goats: influence of a low-protein diet. Agriculture. 2021;11(11):1155. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11111155.

Gebeyew K, Chen K, Wassie T, Azad MAK, He J, Jiang W, et al. Dietary amylose/amylopectin ratio modulates cecal microbiota and metabolites in weaned goats. Front Nutr. 2021;8:774766. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.774766.

Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226(1):497–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64849-5.

Tan B, Yin Y, Liu Z, Tang W, Xu H, Kong X, et al. Dietary L-arginine supplementation differentially regulates expression of lipid-metabolic genes in porcine adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. J Nutr Biochem. 2011;22(5):441–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.03.012.

McCulloch RS, Ashwell MS, O’Nan AT, Mente PL. Identification of stable normalization genes for quantitative real-time PCR in porcine articular cartilage. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2012;3:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-1891-3-36.

Yang C, Cheng Y, Li X, Li H, Yan Q, He Z, et al. Effects of dietary Macleaya cordata extract inclusion on transcriptomes and inflammatory response in the lower gut of early weaned goats. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2021;272:114792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2020.114792.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262.

Gruffat D, Gobert M, Durand D, Bauchart D. Distinct metabolism of linoleic and linolenic acids in liver and adipose tissues of finishing Normande cull cows. Animal. 2011;5(7):1090–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1751731111000073.

da Costa ASH, Bessa RJB, Pires VMR, Rolo EA, Pinto MA, Fontes CMGA, et al. Is hepatic lipid metabolism of beef cattle influenced by breed and dietary silage level? BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:65. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-10-65.

Hiller B, Herdmann A, Nuernberg K. Dietary n-3 fatty acids significantly suppress lipogenesis in bovine muscle and adipose tissue: a functional genomics approach. Lipids. 2011;46(7):557–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11745-011-3571-z.

Vahmani P, Johnson JA, Sutherland BD, Penner GB, Prieto N, Aalhus JL, et al. Changes in the fatty acid composition of steer subcutaneous fat, including biohydrogenation products, are minimal when finished on combinations of corn and barley grains and silages. Can J Anim Sci. 2021;101:362–9. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjas-2020-0013.

Doran O, Moule SK, Teye GA, Whittington FM, Hallett KG, Wood JD. A reduced protein diet induces stearoyl-CoA desaturase protein expression in pig muscle but not in subcutaneous adipose tissue: relationship with intramuscular lipid formation. Br J Nutr. 2006;95(3):609–17. https://doi.org/10.1079/bjn20051526.

Corazzin M, Bovolenta S, Saccà E, Bianchi G, Piasentier E. Effect of linseed addition on the expression of some lipid metabolism genes in the adipose tissue of young Italian Simmental and Holstein bulls. J Anim Sci. 2013;91(1):405–12. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2011-5057.

Bartoň L, Kott T, Bureš D, Řehák D, Zahrádková R, Kottová B. The polymorphisms of stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD1) and sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 (SREBP-1) genes and their association with the fatty acid profile of muscle and subcutaneous fat in Fleckvieh bulls. Meat Sci. 2010;85(1):15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.11.016.

Pecka-Kiełb E, Kowalewska-Łuczak I, Czerniawska-Piątkowska E, Króliczewska B. FASN, SCD1 and ANXA9 gene polymorphism as genetic predictors of the fatty acid profile of sheep milk. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):23761. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03186-y.

Dervishi E, Serrano C, Joy M, Serrano M, Rodellar C, Calvo JH. Effect of the feeding system on the fatty acid composition, expression of the Δ9-desaturase, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha, gamma, and sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 genes in the semitendinous muscle of light lambs of the rasa Aragonesa breed. BMC Vet Res. 2010;6:40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-6-40.

Dance LJE, Matthews KR, Doran O. Effect of breed on fatty acid composition and stearoyl-CoA desaturase protein expression in the semimembranosus muscle and subcutaneous adipose tissue of cattle. Livest Sci. 2009;125(2):291–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2009.05.009.

Urrutia O, Mendizabal JA, Insausti K, Soret B, Purroy A, Arana A. Effects of addition of linseed and marine algae to the diet on adipose tissue development, fatty acid profile, lipogenic gene expression, and meat quality in lambs. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156765. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156765.

Giallongo F, Harper MT, Oh J, Lopes JC, Lapierre H, Patton RA, et al. Effects of rumen-protected methionine, lysine, and histidine on lactation performance of dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2016;99(6):4437–52. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2015-10822.

Dervishi E, Serrano C, Joy M, Serrano M, Rodellar C, Calvo JH. Effect of the feeding system on the fatty acid composition, expression of the delta9-desaturase, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha, gamma, and sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 genes in the semitendinous muscle of light lambs of the rasa aragonesa breed. BMC Vet Res. 2010;6:40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-6-40.

Wang Y, Shelby S, Apple J, Coffey K, Pohlman F, Huang Y. Effects of two dietary crude protein levels on finishing performance, meat quality, and gene expression of market lambs. Anim Sci J. 2021;92(1):e13641. https://doi.org/10.1111/asj.13641.

Madeira MS, Pires VM, Alfaia CM, Costa AS, Luxton R, Doran O, et al. Differential effects of reduced protein diets on fatty acid composition and gene expression in muscle and subcutaneous adipose tissue of Alentejana purebred and large white × landrace × Pietrain crossbred pigs. Br J Nutr. 2013;110(2):216–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114512004916.

Ameer F, Scandiuzzi L, Hasnain S, Kalbacher H, Zaidi N. De novo lipogenesis in health and disease. Metabolism. 2014;63(7):895–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2014.04.003.

Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(10):763–77. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2222.

Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J Clin Investig. 2002;109(9):1125–31. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci15593.

Zhang Y, Lei T, Huang JF, Wang SB, Zhou LL, Yang ZQ, et al. The link between fibroblast growth factor 21 and sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c during lipogenesis in hepatocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;342(2):41–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2011.05.003.

Xu Q, Lin S, Li Q, Lin Y, Xiong Y, Zhu J, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 regulates lipid accumulation and adipogenesis in goat intramuscular adipocyte. Anim Biotechnol. 2021;32(3):318–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495398.2019.1691010.

Pérez-Martí A, Garcia-Guasch M, Tresserra-Rimbau A, Carrilho-Do-Rosário A, Estruch R, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. A low-protein diet induces body weight loss and browning of subcutaneous white adipose tissue through enhanced expression of hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21). Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61(8):1600725. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201600725.

Saponaro C, Gaggini M, Carli F, Gastaldelli A. The subtle balance between lipolysis and lipogenesis: a critical point in metabolic homeostasis. Nutrients. 2015;7(11):9453–74. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7115475.

Hocquette JF, Graulet B, Olivecrona T. Lipoprotein lipase activity and mRNA levels in bovine tissues. Comp Biochem Physiol Part B. 1998;121(2):201–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0305-0491(98)10090-1.

Poulsen L, Siersbæk M, Mandrup S. PPARs: fatty acid sensors controlling metabolism. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23(6):631–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.01.003.

McGarry JD, Brown NF. The mitochondrial carnitine palmitoyltransferase system. From concept to molecular analysis. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00001.x.

Lu Z, Ma Y, Li Q, Liu E, Jin M, Zhang L, et al. The role of N(6)-methyladenosine RNA methylation in the heat stress response of sheep (Ovis aries). Cell Stress Chaperones. 2019;24(2):333–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12192-018-00965-x.

Wang X, Zhu L, Chen J, Wang Y. mRNA m6A methylation downregulates adipogenesis in porcine adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;459(2):201–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.02.048.

Zhang M, Zhang Y, Ma J, Guo F, Cao Q, Zhang Y, et al. The demethylase activity of FTO (fat mass and obesity associated protein) is required for preadipocyte differentiation. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133788. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133788.

Shen GS, Zhou HB, Zhang H, Chen B, Liu ZP, Yuan Y, et al. The GDF11-FTO-PPARγ axis controls the shift of osteoporotic MSC fate to adipocyte and inhibits bone formation during osteoporosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol basis Dis. 2018;1864(12):3644–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.09.015.

Kim J, Lee G. Metabolic control of m(6)A RNA modification. Metabolites. 2021;11(2):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11020080.

Sun M, Zhang X. Epigenetic regulation of N6-methyladenosine modifications in obesity. J Diabetes Investig. 2021;12(8):1306–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.13571.

Pendleton KE, Chen B, Liu K, Hunter OV, Xie Y, Tu BP, et al. The U6 snRNA m6A methyltransferase mettl16 regulates sam synthetase intron retention. Cell. 2017;169(5):824–35.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CELL.2017.05.003.

Jiang Q, Sun B, Liu Q, Cai M, Wu R, Wang F, et al. MTCH2 promotes adipogenesis in intramuscular preadipocytes via an m(6)A-YTHDF1-dependent mechanism. FASEB J. 2019;33(2):2971–81. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201801393RRR.

Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, Hon GC, Yue Y, Han D, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505(7481):117–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12730.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Chinese Academy of Sciences, CAS Science and Technology Service Network Initiative, and Innovation Province Project for financial support.

Funding

This study was funded by Chinese Academy of Sciences (Strategic Priority Research Program Grant NO. XDA26040304, XDA26050102), CAS Science and Technology Service Network Initiative (KFJ-STS-ZDTP-075), and Innovation Province Project (2019RS3021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data acquisition, Data analysis and Writing - original draft, HM, YC, and TZ: Animal experiments and data acquisition, YC and QY: Review and editing, ZH and ST: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, review and editing, ZT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Subtropical Agriculture, Chinese Academy of Sciences (ISA-202020) and all applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Primer sequences and amplicon information.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gebeyew, K., Yang, C., Mi, H. et al. Lipid metabolism and m6A RNA methylation are altered in lambs supplemented rumen-protected methionine and lysine in a low-protein diet. J Animal Sci Biotechnol 13, 85 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-022-00733-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-022-00733-z