Abstract

This systematic review identifies the potential sustainability challenges lower-tier suppliers and buying firms face in multi-tier crop agri-food supply chains. The first stage applied systematic mapping, and based on a sample of 487 academic articles from 6 databases, identified a less-researched area through empirical analysis. Secondly, a systematic evidence review synthesis methodology was used to synthesise the identified sustainability challenges from 18 qualitative studies focusing on the crop agri-food sector. A complex adaptive system, triple-bottom-line approach, and environmental, social, and governance sustainability models were applied to understand the nature of multi-tier supply chain structures and then identify sustainability challenges. Four major dimensions of sustainability challenges (social, economic, environmental and governance) for the lower-tier suppliers and buying firms were identified. Disintegration between buying firms and the lower-tier suppliers, predominantly due to their different locations, was found to be the primary reason for sustainability challenges in the crop agri-food sector. The review findings establish a theoretical framework that could serve as a roadmap for future research in multi-tier supply chains across various sectors and geographies, examining potential sustainability challenges and developing governance structures for sustainable development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Crop agri-food supply chains in a global context have witnessed a dramatic increase in multi-tier suppliers' involvement in the process of product formation (Boström et al. 2015; Grimm et al. 2014; Mena et al. 2013; Wilhelm et al. 2016). These suppliers are considered a major driving force for buying firms to achieve competitive advantages and also contribute to an organisation's overall success (Chacón Vargas et al. 2018; Feola 2015; Rashidi et al. 2020; Rueda et al. 2017). However, when these suppliers, particularly at lower tiers, are not managed well by the buying firms, they also cause multidimensional real-world sustainability challenges (Remondino and Zanin 2022). Thus, sustainability in this sector has emerged as a significant business objective to address different stakeholders' concerns, not only at the corporate level (Derqui 2020), but also in maintaining compliance throughout the business operations (Tovey 2009).

In recent years, different scholars have attempted to structure a brief outline of sustainability from the nascent idea of the Brundtland Commission report of the United Nations, which aims for sustainable development with the agenda of ‘our common future’ (WCED 1987). Nevertheless, it is now well-established that the concept of sustainability is holistic and encompasses a variety of interpretations, albeit with different foci (Lozano 2015). This view is supported by Scoones et al. (2020), who subsequently argue that sustainability and its transformation are based on a business's systemic and structural approaches. The systemic approach gives a broader interpretation of sustainability in a business and draws environmental, social, and economic orientations of sustainability. In contrast, the structural approach sets a governing mechanism to manifest a systemic approach (Scoones et al. 2020). Nonetheless, the integration of structural and systemic approaches to sustainability in crop agri-food supply chain literature is insufficiently documented.

Several studies have emphasised that the first step towards sustainable growth for a business is to understand the nature of sustainability challenges that may exist in its geographically fragmented multi-tier supply chain structures (Boström et al. 2015; Schramm et al. 2020). The studies of Mena et al. (2013) and Grimm et al. (2014) provide a brief insight into the structure of a multi-tier supply chain: the first tier is the relationship between the buying firm and its suppliers, the second tier is the relationship between these suppliers and their sub-suppliers or lower-tier suppliers, and so forth. However, most of the research on supply chain networks has focused only on buyer and first-tier supplier relationships for sustainable business so far. Whereas the greater the number of supply chain tiers, the higher the probability of facing sustainability challenges (Sarpong 2014). Studies by León Bravo et al. (2021), Canto et al. (2021) and Grimm et al. (2016) have highlighted multiple sustainability challenges related to social equity, environmental health, and economic wealth emerging from beyond tier-one suppliers in agri-food businesses. Predominantly, these challenges were operational and witnessed due to divergent institutional and cultural backgrounds of the different lower tiers of supply chains. Geographically fragmented supply chains require an effective governance structure to establish operational collaborative mechanisms across multiple tiers, contributing to supply chain network-level objectives and organisational-level competitive advantages (Boström et al. 2015; Grimm et al. 2016; Meinlschmidt et al. 2018; Pattberg and Mert 2013; Sancha et al. 2019).

Multi-tier supply chains, when operating from different geographies, often involve 'governance at a distance', which can result in a disconnect between buying firms and their lower-tier suppliers, leading to various sustainability challenges for both (Boström et al. 2015; Bush et al. 2015). The research of Mena et al. (2013) has revealed that shorter supply chains might help businesses expand more sustainably. For example, sourcing products directly from local farmers decreases the complexity of the supply chain and makes communication with suppliers and the traceability of the product much more accessible. Given the magnitude of economic globalisation to achieve organisational-level competitive advantages, the return to local and shorter supply chains is not likely to be a panacea for most supply chains (Boströmet al. 2015). Governance mechanisms will have to face indirect and distant interactions among various supply chain actors and manage sustainability challenges (Boström et al. 2015). To address such challenges, arrangements could be made through advanced information flows on production, a comprehensive understanding of sustainability challenges, new ways of mediating communication among different tiers and generic governance ‘standards’ (Boström et al. 2015). However, sustainability risks related to such abstracts and mediated communication are significant, and vigorous academic debate has highlighted the importance of the effective governance structure of buying firms for sustainable development, mainly when the lower-tier suppliers are from developing countries (Mylan et al. 2014). These structural implications for buying firms need to develop in proximity and in sensitivity to the norms and practical circumstances of production. The governance of lower-tier suppliers need to occur in a systemic way and relate to social equity, environmental health, and economic wealth in crop agri-food businesses, without which any sustainability improvement is unlikely to materialise (Vellema and Wijk 2014).

Individual studies have highlighted various sustainability challenges for buying firms and lower-tier suppliers in agri-food supply chains. However, a synthesis of the literature which provides a comprehensive picture of influencing systemic and structural orientations, and their research streams in multi-tier crop agri-food supply chains, has not emerged to date. A recent study by Grohmann et al. (2023) highlights the significant role of governance in achieving sustainability compliance. However, the study specifically focuses on the broader German agri-food sector and emphasises various sources of trust in effective governance for sustainability compliance. This research also calls for the need to develop a broader framework for identifying hidden sustainability challenges. Similarly, the study conducted by Alsayegh et al. (2020) explores the relationship between governance and the economic, environmental, and social performance of various sectors in Asian firms. Nevertheless, the studies did not review the specific barriers for lower-tier suppliers and performance challenges of buying firms for sustainability in the crop agri-food sector.

To address the identified gaps in the literature, this research employs a descriptive review methodology that combines a systematic map and a review evidence synthesis. The following research questions have guided this systematic study:

RQ1. What are the sustainability challenges for the lower-tier suppliers of the crop agri-food sector?

RQ2. What are the governance challenges for the buying firms in their multi-tier crop agri-food supply chains?

The primary purpose of this review is to develop a comprehensive outline of sustainability challenges prevalent in the crop agri-food sector, for both the buyers and their lower-tier suppliers. This paper contributes to the literature in multiple ways. To understand the context of the study, this review primarily adopted the complex adaptive system (CAS), which referred to the collective engagement of multiple tiers involved in exchanging products and services across different stages of the crop agri-food supply chain (Choi et al. 2001). This engagement shapes the actions of various stakeholders within the supply chain structures and determines how buying companies control these actions for the sustainability of their supply chains (Nair and Reed-Tsochas 2019). The interconnected features of the complex adaptive system in this review established the roles of different tiers of suppliers in various supply chains and the dynamics of their relationship with buying firms. Moreover, by drawing a logical discussion from existing literature, this study aims to establish theoretical and practical insights into the nature of these challenges for future research. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: “Material and methods of the review” section describes the methodology; “Discussion” section presents the results given the research questions, research propositions and the comprehensive framework; and “Conclusion and future research directions” section discusses the major findings and concludes the review with recommendations.

Material and methods of the review

Modelling sustainability: a two-stage systematic descriptive review

Subsequent to outlining the review objectives, this investigation systematically developed theoretical models based on systemic and structural sustainability approaches to guide the review process. These models also played a crucial role in refining the inclusive eligibility criteria for the review. A triple-bottom-line sustainability approach was used to address RQ1 of the review. The triple-bottom-line approach remained invaluable in analysing the systemic nature of sustainability challenges, holistically considering the social, economic, and environmental aspects (Scoones et al. 2020; Gimenez et al. 2012). Few studies have taken a ‘systemic approach’ to exploring and managing multifaceted sustainability challenges that cover all aspects of the triple-bottom-line approach (Seuring 2013; Desiderio et al. 2022). To answer RQ2, the review established a link between the environment, social and governance (ESG) model and the triple-bottom-line approach by adopting Gellynck and Molnár's (2009) chain governance model. The chain governance mechanism investigating the ESG model is viewed from a multi-tier network perspective. Further, it reveals how ‘structural orientations’ of the buying firms influence systemic integration, interdependencies and relationships of different stakeholders, leading to a better understanding of sustainability challenges and possible solutions (Boström et al. 2015; Degli Innocenti and Oosterveer 2020; Gellynck and Molnár 2009; Gruchmann 2022; Tachizawa and Wong 2014; Vlachos and Dyra 2020).

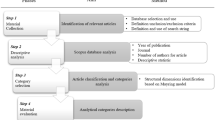

This research followed a two-stage systematic descriptive review methodology to investigate the sustainability challenges in the multi-tier agri-food supply chain (James et al. 2016; Moghri et al. 2016; Shemilt et al. 2014). The research was based on a desktop review of the agri-food literature through several steps. A comprehensive systematic protocol was established for the credibility and transparency of the research findings, highlighting preliminary research gaps. The protocol followed Cochrane's systematic review guidelines to keep the research focused and methodological transparency throughout the research process (Henderson et al. 2010). Then, an exploratory and investigative systematic mapping review of the agri-food literature was conducted, focusing on recent research patterns and establishing the literature gaps. This was followed by an interpretive evidence review synthesis of primary studies of the crop agri-food sector based on 6 databases.Footnote 1

Systematic map (stage one)

The systematic review map identified the nature of multidimensional sustainable agri-food supply chain literature systematically by classifying and then categorising large datasets into focused clusters of sub-sets for the second stage of evidence synthesis. The systematic map used an ‘a priori’ methodology that reduced the likelihood of bias and increased the transparency of the approach to achieve study objectives (James et al. 2016). To establish a timeline for data collection, the review map borrowed the concept of 'completeness of systematic reviews', which signifies a relevant research value that emerges over time (Bashir et al. 2018). Following a substantial inquiry, the literature selected for analysis originates from January 2008 to 28th of February 2022. This temporal demarcation was chosen after an extensive search, as scholarly attention towards the terms ‘multi-tier supply chain’ and ‘sustainability challenges’ markedly intensified during this period. The selected literature encapsulates a comprehensive and contemporaneously relevant spectrum of academic contributions (n = 2068). A database was developed to maintain the records of each study using the different search engines used in this review.

The primary search strings were designed by considering a PICO (Population, intervention, comparator, and outcome) framework,Footnote 2 which is a key driver in collecting the relevant and eligible data in a systematic study (Vriezen et al. 2019). Primarily, this map used a search engine, Google Scholar, to test the specificity and sensitivity of the search strings and then develop subsequent search strings.Footnote 3 This study also considered a comprehensive Boolean structure and truncation (*) in bibliographic databases for the maximum accuracy of search results. Inclusive predefined eligibility criteria, 'inclusion and exclusion', were planned for the data collection to retrieve relevant data (Booth 2016). Grey literature, theses, books, and studies by a single author were in the exclusion criteria. Studies that highlighted the sustainability challenges in multi-tier agri-food supply chains were included. The review only considered articles written in the English language.

Data collection and screening of the studies

A comprehensive article search was conducted from the 1st of March to the 27th of March 2022, providing a primary sample (n = 2068),Footnote 4 which was then exported to citation management software (Mendeley V.2.84.0). No external sources, including books, were used to acquire further data. A total of 163 duplicates were removed, leaving a remaining dataset of 1905 studies for screening. Then, 1243 studies, which included grey literature, theses, books, and works by individual authors, were excluded. In the second phase, title and abstract screening of the remaining 662 studies were performed concurrently. This phase followed the guidelines of Polanin et al. (2019) as a screening process. For instance, did the title indicate the relevance of the research? Did the abstract indicate that a proposed inclusion framework was used? Have any of the segments from the PICO framework been highlighted in the abstract? This phase also adopted a three-way format for screening: (a) yes, (b) no, and (c) unsure. Unsure studies were briefly discussed with the team members before making further decisions. The collaborative ‘brainstorming’ allowed for a transparent and structured screening process, and 175 studies were eliminated. Finally, 487 articles were left for full-text evaluation.

The systematic mapping stage performed two sets of Cohen kappa reliability checks to ensure validity and reliability. A Kappa score, usually between 0.61 and 0.80, represents substantial agreement (Cohen 1960). The first set of reliability scores during titles and abstract screening averaged 0.73 (range of 0.64–0.78 across 3 secondary assessors). In the second phase of categorising the studies, the kappa interrater reliability score averaged 0.76 (range of 0.71–0.81 across 3 secondary assessors).

Data organisation and empirical analysis

All the data from 487 studies were recorded to collate relevant information about study designs, approaches, units of analysis, methodologies, and the scope of articles. Descriptive statistics were calculated, and the results were summarised and presented tabularly in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation 2016). Multiple rounds of classifying and categorising the dataset were performed to identify a sample of n = 487 following a comprehensive eligibility frameworkFootnote 5 and models. Initially, in the classification phase, the review employed a user-based multi-label text classification framework developed by Bradford et al. (2022) and Zhang et al. (2022) to organise a research dataset. This framework relies on label surface names and descriptions during inference to structure large data sets effectively. Each study was individually reviewed and annotated with various labels according to their characteristics. Adhering to this framework, the research primarily separated 249 studies; among them, 113 were grounded in secondary data, and 136 focused on sectors other than crop agri-food, mainly livestock, meat and dairy. The studies reliant on secondary data (n = 80) predominantly followed a systematic literature review approach.

The remaining 238 studies underwent categorisation using Eggert and Alberts’s (2020) ‘Taxonomy of concept matrix in research.’ This conceptual framework, known as a concept matrix, represents a logical and highly descriptive approach to managing extensive research data. It operates through an inductive method. Following the inductive manner, this research grouped articles based on key concepts, including research approach, study design, area of research/unit of analysis, nature of data (e.g. qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods), and findings. This comprehensive application of the concept matrix facilitated a clear and detailed understanding of the dataset, enhancing the ability to analyse and interpret the research landscape. The deductive approach was applied using the quantitative method (n = 139) and was mainly used as a theory testing process, particularly in apparel, minerals, and multiple automotive industries. This technique further applied empirical and analytical methods, mainly considering regression, multiple modelling, and factor analysis for the conclusion. Various survey-based studies following deductive reasoning have also been carried out in this review investigating sustainable farming models, particularly in the dairy and livestock sectors. The high number of deductive paradigmatic preferences through quantitative modelling was possibly due to the less intensity required in formulating such methods (Bryman and Bell 2011).

The inductive approach employing the qualitative research technique was relatively less used than the deductive approach (n = 31). This may be due to the multidisciplinary nature of qualitative research (Vallet-Bellmunt et al. 2011), which made its employability difficult to acquire generalisability of a particular research domain by controlling all sustainability variables (Tarifa-Fernandez and Burgos-Jiménez 2017), particularly in social and cultural constructs. Following the case study approach, the phenomenological paradigm was the preferred method. A mixed-methods research strategy mainly highlighted the sustainable policies and fair-trade standards (n = 22). The low usage of this research method exposes budget and time constraints (Doyle et al. 2009) and some practical difficulties due to the immaturity of the multi-tier supply chain literature. A lesser-known abductive approach was also used in a few studies that investigated the existing theoretical framework and findings suggesting alternative hypotheses for further investigation (Spens and Kovács 2006).

Some studies did not meet the study’s criteria and were placed in a general research category (n = 44). Most of the studies received researchers’ attention on the COVID-19 impact (n = 7) on sustainable multi-tier supply chains, emphasising that natural interventions can seriously damage the entire supply chain. To mitigate such situations, companies need a contingency plan to manage the impacts of pandemics. Interestingly, the least importance found in the map data was the challenges of modern slavery (n = 3) in the supply chain, particularly in the agriculture, apparel, and mining sectors.

Although most of the studies in the review were atheoretical, various theoretical frameworks of different theories were also employed. For instance, ‘descriptive’ (Schaltegger et al. 2017), 'instrumental' (Jones et al. 2018), and ‘normative aspects’ (Wongprawmas et al. 2015) of ‘Stakeholder theory’ (Freeman 1984) followed by ‘coercive’ (Park-Poaps and Rees 2010), ‘normative’ (Sherer et al. 2016), and ‘mimetic’ (Latif et al. 2020) isomorphism aspects of ‘Institutional theory’ (Meyer and Rowan 1977) were mainly applied in the automotive and technological sectors. These features predominately emphasised the legitimate and autonomous cooperation (Fuller et al. 2022) from different stakeholders in the supply chain for sustainability compliance. The ‘structural’ (Monaghan et al. 2017) and ‘relational’ (Asamoah et al. 2020) embeddedness features of ‘Social network theory’ (Durkheim 1964), and the principal and agent relationship of ‘Agency theory’ (Eisenhardt 1989), were mainly used in the apparel and livestock sectors of collectivistic societies. These characteristics were focused on analysing the moral hazards and reducing the risks of opportunism in geographically fragmented supply chains. The primary feature of 'Transaction cost economics theory' (Williamson 2008), being the calculation of the value of all aspects of the goods and services involved in the transaction (Meinlschmidt et al. 2018) in a transparent way, also contributed to achieving buyer and supplier ‘trust’ (Campos and Mello 2017; Grohmann et al. 2023) in their business supply chains. Different features of resource dependence and resource-based theory were also used in multiple studies.

The multi-tier supply chain structure of the crop agri-food sector and the systemic nature of sustainability challenges have received limited attention in the existing body of literature. Although many systematic studies highlighted sustainability challenges, most of them primarily dealt with one or two dimensions of sustainability. These studies predominantly focused on the apparel and livestock sectors, while the crop agri-food sector received comparatively less attention. The qualitative aspect of the research, including systematic evidence review synthesis and longitudinal studies focusing on this sector, was absent from the corpus of literature. The literature could also not represent marginalised stakeholders, such as lower-tier suppliers, farmers, and low-income groups, and their challenges were not adequately highlighted. Much of the literature completely ignored their presence in sustainable development. The absence of qualitative research presents an opportunity to uncover the structural and systemic nature of sustainability challenges buyers and suppliers face in the crop agri-food sector. This could further contribute to a comprehensive understanding of sustainability challenges in this sector. The comprehensive empirical analysis of the systematic map not only eliminated the coverage bias of data but also remained focused on avoiding sample saturation and offered a sample of 31 qualitative studies for the next stage to answer predefined research questions. Table 1 illustrates the nature of studies categorised and empirically analysed in the systematic map.

Review evidence synthesis (stage two)

A sample of 31 qualitative studies was reviewed and assessed for quality appraisal. A predefined comprehensive set of exclusion and inclusion criteria identified 18 studies that met the coding requirements for review evidence synthesis to answer the research objectives. These selected studies were based on the qualitative interpretive and phenomenological paradigms, focusing specifically on the crop agri-food sector. Phenomenological and interpretive paradigms increase the understanding of a phenomenon and interpret how things connect and interact in a real setting (Hannes and Lockwood 2011). The crop agri-food sector was the exclusive unit of analysis in 17 studies published between 2011–2021. One study by Mena et al. (2013) was also included after a mutual agreement among the researchers based on three agri-food supply chains, of which two focused on crop agri-food. This study provided valuable insights into how multi-tier supply chains operate across different geographical areas. More significantly, by analysing the concept of ‘triads’ as proposed to be the fundamental unit within multi-tier supply chains, this study highlighted the distinct roles performed by various actors. It focused on the relationships between buyers, suppliers, and sub-suppliers within multi-tier agri-food supply chains. These concepts were considered in this review to better understand the functioning of these complex supply chains.

The selected studies were imported into qualitative data analysis software, NVivo (R1.7), and a comprehensive qualitative coding structure was devised. The review initially employed a deductive coding strategy, guided by an 'a priori' framework, to extract descriptive findings of the studies. This strategy described each study, covering the sampling strategy, theoretical framework, supply chain structures, the unit of analysis, data collection/analysis methods and sustainability challenges. Following this, a recursive inductive coding approach was employed to assess whether additional codes were needed or if some codes were to be merged or eliminated for interpretative coding consistency (Maher et al. 2018). The codes were compared to multiple sustainability concepts and theories in this phase to ensure alignment before generating analytical categories. Finally, an extensive relational analysis of codes was performed, and latent codes were examined to form a unified thematic structure of codes for interpreting sustainability challenges. A codebook was generated to check the reliability of the data before interpreting it. A PRISMA-type flowchart (Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis), as guided by Moher et al. (2009), was created to indicate each step of this study (Fig. 1).

Descriptive findings of the review evidence synthesis and discussion

The distribution of published studies across different years revealed interesting patterns. The maximum number of studies was observed in 2021 (n = 5), indicating a growing interest in sustainable development. Regarding publication sources, most of the cited papers were published in EbscoHost and Emerald journals (n = 7). The investigation found an intriguing aspect, most papers were atheoretical, implying that many studies lacked a solid theoretical basis. However, among the theories employed, social network theory emerged as the most utilised (n = 3), indicating its suitability for understanding the complexities of multi-tier business settings. Most research followed the case study approach and targeted Italy and Brazil’s fruit and coffee sectors (n = 3).

Semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions emerged as the preferred approaches in data collection methods. These methods allowed researchers to engage directly with farmers, supply chain officials, and sustainability experts, offering valuable insights into the hidden sustainability challenges and uncovering overlooked aspects. The study by Lanka et al. (2017) in India’s coffee sector recorded the highest number of respondents, 256, underscoring the extensive efforts to capture diverse perspectives and experiences related to sustainability challenges. Thematic content analysis was the primary analytical technique employed in the reviewed studies (n = 6), and snowball and purposive sampling were the preferred sampling techniques (n = 4). Furthermore, the range of supply chain tiers varied across the studies. The study by Mena et al. (2013) explored at least three tiers within the supply chain, while Grabs and Carodenuto (2021) analysed a maximum of seven tiers. This variation reflects the diverse structural arrangements and complexities within the crop agri-food sector's supply chains.

Given the ‘complex adaptive system’ establishing the roles of multiple tiers of suppliers in different supply chains, the dynamics of their relationship with buying firms, and exploring the sustainability challenges in complex multi-tier supply chain structures were the absolute contributions of this research (Choi et al. 2001; Mena et al. 2013). By implementing the ‘Triple-bottom-line approach’ concept, RQ1 explored three interlinked dimensions of major sustainability challenges for lower-tier suppliers: economic, environmental, and social. By integrating the ESG model with the TBL approach and employing chain governance, RQ2 highlighted the multidimensional nature of sustainability challenges faced by buying firms in terms of governance. The comprehensive review analysis also highlighted that the primary reason for these challenges was the missing integration link between buyers and lower-tier suppliers, mainly due to their cross-border and different geographical locations. This was primarily due to two reasons. Firstly, the buying firms had no effective governance structure in their multi-tier supply chains to comply with the sustainability challenges in a cross-border context. Secondly, buying firms tended to have contractual business relationships with only the first-tier suppliers, in which lower-tier suppliers were often not bothered and frequently caused multidimensional sustainability challenges.

These challenges significantly shaped the sustainability landscape of lower-tier suppliers and buying firms in the crop agri-food sector. The subsequent section analyses and discusses these challenges. The descriptions of the findings are summarised in Table 2.

Discussion

RQ1: What are the sustainability challenges for the lower-tier suppliers of the crop agri-food sector?

Economic sustainability challenges

A total of 14 studies identified many economic sustainability challenges, subsequently synthesised into three major categories. Those were economic exploitation for farmers, limited economic incentives for farmers and high-cost agricultural practices highlighted in Table 3. The studies of Sousa et al. (2018) and Sozinho et al. (2018) specifically examined the economic challenges faced by Brazilian sunflower and sugarcane growers. Their research highlighted unique challenges specific to the farmers and growers, shedding light on their distinct circumstances within the multi-tier supply chains. The lack of job plans and proper schooling opportunities for the farmers' children, and their lack of land ownership rights, significantly compromised their economic condition and heightened their vulnerability (Sozinho et al. 2018). The farmers were only considered 'commodities with no value'. This highlighted the 'social capital deficits' (Johnson et al. 2018) faced by farmers which has contributed to their compromised economic condition (Johnson et al. 2018). Integrating community development projects, such as providing basic business infrastructure to farming communities and supporting vocational training programmes for young farmers, could foster socio-economic capital and ensure long-term economic sustainability for lower-tier suppliers and their communities (Johnson et al. 2018). Moreover, the buying firms should emphasise fostering partnerships with local agricultural cooperatives by involving multiple intermediaries beyond tier-one suppliers and community-based organisations (Mirkovski et al. 2015). This strategy would enhance the bargaining power of smallholders, enabling them to negotiate fair prices and more favourable terms. Such collaborative approaches contribute to the economic sustainability of smallholders by promoting a more supportive and equitable supply chain environment (Alsayegh et al. 2020; Raihan and Tuspekova 2022). A comparative analysis of Sjauw-Koen-Fa et al. (2018) also reported numerous other economic challenges in India and Indonesia's black soybean and tomato industries. Those were mainly related to high spraying costs and delayed payments for their products, which always kept farmers under the debt pressure of local wholesalers. The decreased remuneration for growers further compounded the difficulties faced by the farmers (Canto et al. 2021). This emphasised the importance of 'trust' (Grohmann et al. 2023; Hoffmann et al. 2010) and 'organisational cooperation' (Huang et al. 2016) regarding 'social capital' within multi-tier supply chains (Canto et al. 2021; Gulati et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2018).

Challenges such as the lack of renewable energy and limited use of biodegradable materials used for fruit, vegetables and balsamic Vinegar production by Italian farmers also underscored the significance of adopting a comprehensive approach to economic sustainability beyond the narrow focus on monetary considerations (León Bravo et al. 2021; Kristensen and Mosgaard 2020). To reduce reliance on high-cost fossil fuels, decrease greenhouse gas emissions, and promote energy self-sufficiency, it is beneficial to encourage and support farmers to invest in renewable energy technologies such as solar panels or wind turbines (Broad et al. 2022; Melomey et al. 2022; Tanneberger et al. 2022). By considering the broader social implications due to economic exploitation, as cited in Sozinho et al. (2018) and Sousa et al. (2018), stakeholders of multi-tier supply chains should take proactive measures to address the exploitation of farmers and provide basic health facilities, schooling, and job opportunities for their children. Economic exploitation could pose detrimental social sustainability threats, particularly in developing countries (Venkatesha et al. 2019). According to the stakeholder approach, to mitigate such challenges, 'normative aspects' (Sherer et al. 2016) in a supply chain (based on ethical characteristics) could play a significant role in fulfilling 'Instrumental aspects' (demands and expectations) (Ricart and Rico-Amorós 2022).

The review findings further emphasised that lower-tier suppliers have been adversely affected by the lack of financial resources, limited incentives, and reduced product remuneration (Blasi et al. 2015; Challies and Murray 2011; Manning and Reinecke 2016; Mena et al. 2013; Sousa et al. 2018; Sozinho et al. 2018; Wongprawmas et al. 2015). According to the resource-based perspective, farmers should have access to 'affordable long-term credit', subsidies, and crop insurance programmes for necessary 'resources' to promote economic sustainability (Eryarsoy et al. 2022; Forkuor and Korah 2021). This support could enable farmers to invest in modern farming technologies, equipment, and infrastructure and expand their operations (Forkuor and Korah 2021). In addition to financial support, improving their market access is significantly important (Raihan and Tuspekova 2022). This can be achieved by developing adequate infrastructure, transportation, and grain storage facilities (Kendall et al. 2022). Balance theory asserts that these enhancements could enable farmers to reach broader markets, secure fair prices for their products, and create a more 'balanced' economic environment (Elahi et al. 2022; Ferreira et al. 2016; Forkuor and Korah 2021; Kendall et al. 2022; Phillips et al. 1998). To save lower-tier suppliers from further economic loss and exploitation of their quality products, as mentioned in the studies of Lanka et al. (2017) and Sousa et al. (2018), a fair pricing mechanism should also be established to reflect the quality of their products accurately (Forkuor and Korah 2021; Kendall et al. 2022).

The sustainability managers can also adopt ‘circular economy’ principles to reduce waste and promote the recycling and reuse of materials within the supply chain (Sgroi 2022). This may include collaborating with suppliers to implement closed-loop systems, where products are designed with recyclability in mind (Selvan et al. 2023; Sgroi 2022). Moreover, managers could also consider diversifying farmer income sources by exploring alternative crops or products with higher economic value, particularly in the developing world (Peiris and Dayarathne 2023). Encouraging the adoption of precision agriculture technologies can optimise resource use, reduce costs, and enhance overall economic efficiency. Knowledge-sharing platforms and networks among lower-tier suppliers exchange best practices and collectively address common challenges (Pakseresht et al. 2023). Within a similar mechanism, investing in technology solutions, such as blockchain, can provide transparency in the supply chain, allowing consumers to trace the origin of products and ensure adherence to sustainability standards (Pakseresht et al. 2023).

Environmental Sustainability challenges

The collective findings of 12 studies in this review highlighted the wide-ranging challenges associated with environmental sustainability presented in Table 4 that were pervasive and widespread, affecting various regions across the globe. These were linked to climate change, soil erosion, deforestation, product waste and severe hydrological issues. Primarily, the detrimental effects of deforestation emerged as a significant environmental concern, given its role in natural habitat destruction, loss of biodiversity, and contributions to greenhouse gas emissions. These challenges were prevalent mainly in Brazil, India, Indonesia and Ivory Coast industries of coffee, soybean, tomato and sugarcane (Gboko et al. 2021; Manning and Reinecke 2016; Sjauw-Koen-Fa et al. 2018; Sozinho et al. 2018). Furthermore, product and water waste challenges were identified as key areas requiring mitigation strategies to ensure environmental sustainability, particularly in the sunflower, raspberry and fruit/vegetable sectors of Brazil, Chile, Italy, and Thailand. The lack of understanding of lower-tier suppliers about sustainable agricultural practices to protect the environment was identified as the underlying cause of land degradation and drought conditions in India, Brazil, and the business operations of multinationals (Canto et al. 2021; Gboko et al. 2021; Lanka et al. 2017; Manning and Reinecke 2016; Sozinho et al. 2018). Recognising the challenge of deforestation, buying firms can engage in community-based conservation initiatives. This may involve collaborating with local communities in regions like Brazil, India, Indonesia, and Ivory Coast to implement sustainable forestry practices. These countries are considered more collectivistic, and a community-based approach could bring productive results. By supporting afforestation projects, promoting responsible logging, and providing alternative livelihood options, buying firms can contribute to preserving natural habitats and biodiversity and mitigating the adverse effects of deforestation on the environment.

Considering the vulnerability of smallholders in developing countries to climate change, buying firms can take a proactive role in promoting climate-resilient agricultural practices (Goswami et al. 2023). Investing in research and development to identify and disseminate crop varieties that are more resistant to climate extremes would also bring positive results. Providing smallholders access to these resilient seeds and training on climate-smart farming techniques can enhance their capacity to adapt to changing environmental conditions and promote long-term sustainability (Hellin et al. 2023).

Specific studies conducted within distinct crop agri-food sectors further contributed valuable insights into environmental sustainability challenges. For instance, the studies of Manning and Reinecke (2016) and McLoughlin and Meehan (2021) focused on the Cocoa and coffee sectors of multinational firms, identifying significant soil erosion challenges, predominantly missing waste management mechanisms, and avoiding harmful fertilisers. Another significant environmental sustainability challenge was the emissions of greenhouse gases from using old agricultural machinery and the pollution of clean water in canals caused by the disposal of food waste by growers in Brazil, India, Indonesia, and Thailand’s industries of coffee, tomato and vegetable. Similarly, León Bravo et al. (2021) and Sozinho et al. (2018) conducted their studies in Italy and Brazil, investigating the vegetable and sugarcane sector, respectively. Their findings highlighted distinct hydrological challenges, including using polluted water and extensive deforestation, significantly affecting environmental sustainability. The research conducted by Mirkovski et al. (2015) and Lanka et al. (2017) emphasised the importance of effectively adopting sustainable agricultural practices and implementing interventions to address environmental issues, particularly in cross-border settings. Failure to do so could have far-reaching consequences, impacting our immediate surroundings and the entire ecosystem. In response to the significant challenge of food waste in the Brazilian and Indian context, buying firms can initiate localised efforts to promote eco-friendly packaging solutions. Partnering with suppliers and local communities, they can explore sustainable alternatives such as ‘green packaging’ using biodegradable materials or reusable packaging systems (Kim and Ruedy 2023). This addresses environmental concerns and enhances the brand image as environmentally conscious, appealing to consumers who prioritise sustainable practices. Amazone is one of the leading examples of green packaging, achieving its significant competitive advantages (Sarkar 2023).

This analysis emphasised an urgent need for 'collective efforts' and 'coordinated actions' to tackle environmental sustainability challenges associated with climate change and greenhouse gas emissions (Ardoin et al. 2023; DiVito and Ingen-Housz 2021). The findings underlined that 'collective efforts' (Ardoin et al. 2023) and 'coordinated actions' (DiVito and Ingen-Housz 2021) involving 'stakeholders in a business network' (Vasconcelos et al. 2022) are needed to address environmental sustainability challenges and promote awareness programmes tailored for farmers, particularly in developing countries (Nigussie et al. 2021; Wongprawmas et al. 2015). These programmes could promote sustainability and ensure farmers' compliance with environment-friendly agricultural practices in the crop agri-food industries (Johnson et al. 2018). Such initiatives would also enhance 'social capital' by fostering 'cooperation' (Fuller et al. 2022) and 'knowledge sharing' (Blome et al. 2014). Several studies have extensively discussed intensive land use and monoculture farming practices, highlighting their damaging effects on soil erosion and fertility. Encouraging farmers to embrace sustainable farming practices, especially organic farming and crop rotation, can have multiple benefits (Baaken 2022; Broad et al. 2022). These practices minimise environmental impact, reduce the need for chemical inputs, and foster soil health and can be seen as a 'knowledge-based view' to minimise environmental impact and enhance 'soil health' (Blome et al. 2014). Buying firms can significantly advocate organic farming, crop rotation, and agroecological approaches to minimise environmental impact, reduce reliance on harmful fertilisers, and enhance soil health. This approach aligns with a 'knowledge-based view' to minimise environmental impact and promotes a holistic understanding of sustainable agricultural practices among smallholders, fostering long-term environmental sustainability. Immediate attention is required to address various other aspects of environmental sustainability discussed in this review, including traditional irrigation systems leading to water wastage and the utilisation of polluted water in response to water scarcity. Promoting the adoption of efficient irrigation techniques such as 'drip irrigation' and the building of 'water reservoirs' can help farmers conserve water resources (Baaken 2022; Cerdà et al. 2022; Tanneberger et al. 2022).

Social sustainability challenges

Within social sustainability dimensions, severe issues related to human rights, livelihood, health, and safety of the farmers emerged as significant challenges in 13 studies, as highlighted in Table 5. Various studies significantly enhanced our understanding of the social sustainability challenges for farmers in different sectors. For instance, McLoughlin and Meehan (2021) identified multiple challenges related to modern slavery and poor conditions of labourers with no basic facilities available in the cocoa industry of a multinational firm. The presence of child labour and the employment of aged individuals for labour work in the coffee sector of a multinational also raised alarming concerns, especially considering multinationals' so-called claims of sustainability (Brandli et al. 2022; Gboko et al. 2021; Manning and Reinecke 2016; Montiel et al. 2021). Challies and Murray (2011) focused on the Chilean raspberry sector and reported challenges to gender inequality, especially the exploitation of female farmers and unfair wages. In many developing regions that mainly rely on agricultural products, gender inequality is a prevalent social sustainability challenge. For instance, in the South Asian and East African regions, where female workers mainly perform crop sowing, gender inequality and sexual harassment have been reported (Oosterom et al. 2023). Sustainability managers can play an essential role in promoting gender equality by actively engaging in initiatives that empower women in agriculture. Supporting programmes that provide training and resources tailored to female farmers, enhancing their skills and enabling them to take on leadership roles should be encouraged. By fostering inclusivity and gender-sensitive policies, managers contribute to the social well-being of the farming communities, ensuring women have equal access to opportunities and resources (Sultan 2023).

In a study of the Brazilian sugarcane industry, Sozinho et al. (2018) highlighted some distinct challenges related to food security and fewer social benefits for farmers. The studies of León Bravo et al. (2021), Canto et al. (2021), and Sousa et al. (2018) shed light on specific social sustainability concerns in Italian and Brazilian industries of sunflower, fruits and vegetables, emphasising the importance of fair labour practices, community development, and the well-being of workers. Addressing these challenges requires comprehensive actions and systemic changes to ensure the well-being and rights of all 'stakeholders' involved in a multi-tier supply chain. To address such issues, 'farmers' associations' and 'cooperatives' by 'relational' and 'structural embeddedness' of social networking should be encouraged, which can empower them by providing a 'collective voice' (Baaken 2022; Broad et al. 2022; Cerdà et al. 2022; DiVito and Ingen-Housz 2021; Tanneberger et al. 2022) and 'promoting cooperation' (Fuller et al. 2022). These organisations can facilitate their access to 'resources' (Eryarsoy et al. 2022), 'market opportunities' (Elder 2019), and 'shared knowledge' (Blome et al. 2014) while also advocating for farmers' rights and interests (Brandli et al. 2022; Elder 2019; Montiel et al. 2021). A 'policy mechanism' should be implemented to promote the 'fair distribution' of resources, emphasising a 'resource-based view' especially among smallholder farmers and marginalised groups (Elder 2019; Fayet et al. 2022; Montiel et al. 2021). The studies of Challies and Murray (2011), Gboko et al. (2021), Manning and Reinecke (2016) and McLoughlin and Meehan (2021) highlighted the need to address 'social inequalities', 'promote inclusivity' to ensure the well-being of farming communities. Moreover, León Bravo et al. (2021), Challies and Murray (2011), and Sozinho et al. (2018) underscored the significance of ensuring the health and safety of workers and farmers in the fields. Stakeholders in multi-tier supply chains need to prioritise occupational safety measures and provide training on the proper handling of agricultural inputs to mitigate health risks (León Bravo et al. 2021; Sousa et al. 2018).

Opportunistic behaviour of buying firms and misunderstanding within the supply chain actors contributed to a 'trust' and 'commitment' deficit between growers and buyers, particularly in Jordan, Switzerland, and Thailand (Grimm et al. 2014; Grohmann et al. 2023; Jraisat et al. 2013; Wongprawmas et al. 2015). The hidden and exploited intentions of buyers, brokers, the lack of respect for values and culture, and the absence of 'social responsibility' added to the complex social sustainability issues in the coffee, cocoa, and palm oil sectors of a big multinational and sugarcane supply chains of Brazil (Grabs and Carodenuto 2021; Sozinho et al. 2018). Understanding the values of cultural nuances and local contexts is extremely important for social sustainability in agriculture. For instance, big multinationals with production sites in different geographies should tailor their support programmes to align with the cultural values, traditions, and socio-economic structures of the communities they engage with. Promoting cultural diversity by integrating local knowledge could ensure that interventions by the firms resonate with smallholder farmers' specific needs and aspirations. By embracing a culturally sensitive approach, buying firms can build stronger relationships with local communities, enhancing their supply chains' social fabric and sustainability.

Promoting local markets, not only in the crop agri-food sector but also in other food supply chains, could enhance lower-tier suppliers’ income and reduce their 'dependence' on unfair practices of brokers (Fayet et al. 2022; Fuller et al. 2022). Farmer's associations or third parties such as non-government organisations can mediate access to intangible resources such as organisational knowledge and market access (Davis and Cobb 2010) from buying firms by leveraging the value of tangible resources of farmers such as grain and products (Rousseau 2017). A transparent and fair bargaining mechanism can be established while considering both ‘resource dependence’ and ‘resource-based’ perspectives. Farmers should be recognised as active contributors to sustainable development, and their perspectives should be valued (Brandli et al. 2022; Fayet et al. 2022). When implemented in combination and tailored to local contexts, these considerations can help address social sustainability challenges and promote the well-being of farmers, their families, and their communities through collective participation (Fuller et al. 2022; Montiel et al. 2021). These participatory approaches can gain lower-tier communities' confidence and empower them to voice their concerns and aspirations and make suggestions for improvement (Brennan et al. 2023). Such approaches foster a sense of ownership and inclusivity and allow for co-creating sustainable solutions. They also acknowledge smallholders' unique challenges and ensure that social sustainability initiatives are relevant, impactful, and embraced by the community.

RQ2: What are the governance challenges for the buying firms in their multi-tier crop agri-food supply chains?

This review included 15 studies that uncovered multifaceted governance sustainability challenges highlighted in Table 6 These challenges require the immediate attention of buying firms for a sustainable product. Buying firms regularly encountered traceability and monitoring of the product, logistical issues, cultural barriers, knowledge gaps, and technological hurdles, particularly within their lower supply chain tiers.

Buying firms encountered serious governance sustainability challenges with the security and stability of their commodity supply. These issues emerged due to difficulties in monitoring and controlling barriers to observing local market trends of the product, limited assessment mechanisms of global market fluctuation and unreliable market data from their suppliers (Grabs and Carodenuto 2021; Mena et al. 2013; McLoughlin and Meehan 2021; Mirkovski et al. 2015; Wongprawmas et al. 2015). A robust monitoring system could effectively evaluate the marketing trends and inequalities of economic sustainability to address the security and stability concerns related to the supply of agri-food commodities (Mirkovski et al. 2015; Wongprawmas et al. 2015). The studies of Mena et al. (2013), Challies and Murray (2011), and Grabs and Carodenuto (2021) focusing on beer, bread, coffee and raspberry sectors underlined the importance of establishing robust monitoring mechanisms for the traceability of agricultural practices using technology, which could enable transparency and accountability among different tiers throughout the supply chain. An effective blockchain technology in supply chain management can enhance traceability and transparency. This is particularly crucial in regions with a prevalence of smallholders, as blockchain ensures an immutable and secure record of transactions. This technology can mitigate challenges related to information asymmetry and contribute to improved governance in the supply chain (Pakseresht et al. 2023).

Efficient transparency also could ensure the quality, quantity, and safety of the product, as witnessed in wheat, beer and fruit/vegetable sectors in Italy, England and Thailand (León Bravo et al. 2021; Sjauw-Koen-Fa et al. 2018; Manning and Reinecke 2016; Mena et al. 2013; Wongprawmas et al. 2015). With robust mechanisms for traceability and monitoring, buying firms can reduce uncertainties and transactional risks, thereby enhancing transparency and trust throughout the supply chain (Grohmann et al. 2023; Williamson 2008). These efforts aim to optimise economic efficiency and mitigate opportunistic behaviours, which are central concerns of transaction cost economics (Campos and Mello 2017). The other possible way out could also be integrating the agency concept with transactional cost economics (TCE), where buying firms could establish direct contact with lower-tier suppliers, albeit indirectly through another supplier. By leveraging their influence over first-tier suppliers by using them as intermediaries, buying firms can prompt them to 'monitor' (Koh et al. 2012) or 'collaborate' (Mueller et al. 2009) with their lower-tier counterparts (Tachizawa and Wong 2014) in a cost-effective way. Cross-tier collaboration is significant given the challenges associated with monitoring the entire supply chain (Koh et al. 2012; Mueller et al. 2009). Buying firms may also pressure their intermediaries to enforce environmental or social certification requirements for their lower-tier suppliers. This approach aligns with the concept of an 'open triadic structure' proposed by Mena et al. (2013). Another managing concept of a multi-tier supply chain through third-party certification is supported by Tachizawa and Wong (2014). Developing localised and context-specific certification systems tailored to the unique challenges of smallholders can be instrumental. Conventional certification processes might be resource-intensive and less adaptable to diverse farming practices, mainly in the developing world. Engaging the local government representatives in creating certification frameworks that consider smallholder agriculture's socio-economic and environmental context ensures that sustainability standards are met without imposing unrealistic burdens. This approach can foster a sense of ownership and compliance among smallholders.

Communication gaps brought information asymmetry between buying firms and their lower-tier suppliers, which caused buying firms to have limited knowledge about suppliers' culture and learning complications. This was mainly emerging due to geographically dispersed lower-tier suppliers (León Bravo et al. 2021; Challies and Murray 2011; Gboko et al. 2021; Grimm et al. 2014; Jraisat et al. 2013; Manning and Reinecke 2016; Mena et al. 2013; Mirkovski et al. 2015; Sousa et al. 2018; Wongprawmas et al. 2015). Leveraging mobile technology or introducing electronic resources (e-chats) for direct communication, particularly between buying firms and smallholders at lower tiers, can bridge information gaps (Li et al. 2023). This view aligns with ‘direct management’ (Tachizawa and Wong 2014) and ‘closed management’ (Mena et al. 2013), both in the distinct geographies of inter-country or intra-country multi-tier supply chains. E-chat sources could be platforms for sharing real-time market information, weather forecasts, and best agricultural practices. This direct communication channel empowers smallholders with timely insights, allowing them to make informed decisions. It also facilitates a collaborative approach to problem-solving and builds a stronger relationship between supply chain actors.

The varying cultural specificities of different sourcing markets, including language barriers, lack of awareness of consumer demands and learning complications of suppliers, caused significant operational challenges for the buying firms, particularly in Thailand's fruit and vegetable sectors (Wongprawmas et al. 2015). These specificities and operational challenges in different sourcing markets can also be analysed through the lens of CAS, where supply chain governance adapts and self-organises their operations in response to sustainability challenges within their resources (Boström et al. 2015). The resource-based view further emphasises the 'strategic value' of 'resources' and 'capabilities' within organisations in which by sharing knowledge and promoting collaboration (Grimm et al. 2014) with suppliers, buying firms can enhance supplier capabilities, improve information exchange, and drive sustainable farming practices in cross-border supply chains (Gabler et al. 2022). Buying firms could embrace complexity by fostering flexibility, resilience, and adaptability within their supply chains, enabling them to effectively navigate cultural barriers and respond to market demands in their lower tiers (Nair and Reed-Tsochas 2019). Moreover, effective communication among different supply chain tiers is an established concept in mitigating cultural and geographical barriers, particularly in fostering social and environmental sustainability (Challies and Murray 2011; Mena et al. 2013). Effective communication among different tiers of the supply chain aligns with the principles of social network analysis, as it highlights the significance of 'collaboration', 'trust', and 'bridging knowledge gaps' to moderate information asymmetry (Asamoah et al. 2020; Grohmann et al. 2023; Monaghan et al. 2017). This strategy was effectively used in the study of Mena et al. (2013) in the bread and beer sectors of the UK.

To mitigate operational challenges, Steinberg (2023) proposed a multi-level governance approach in the multi-tier supply chain context, combining 'network analysis' (Monaghan et al. 2017) and an 'indirect governance' (Boström et al. 2015; Tachizawa and Wong 2014) structure. This approach is primarily driven by a polycentric theoretical framework in international business (Ostrom 2010). The multi-level governance approach involves small, medium, and large supply chain units with the autonomy to establish and enforce rules within their scope (Ostrom 2010). Decision-making power is distributed across different levels, influencing local cultural specificities and outcomes (Nair et al. 2009). It also examines intersections and interactions between various supply chain levels. This approach could enhance buying firms' understanding of drivers of variation in social and environmental consequences within their multi-tier supply chain (Alsayegh et al. 2020; Wilhelm et al. 2016).

Inadequate roads and poor telecommunication conditions in Chile, India, Indonesia, and Ivory Coast sectors of soybean, tomato, coffee, and raspberry emerged as frequently encountered logistics challenges (Challies and Murray 2011; Gboko et al. 2021; Sjauw-Koen-Fa et al. 2018). Limited space in crop-carrying trucks and long distances between the main road and the fields also caused severe delays in the delivery of products (León Bravo et al. 2021; Grabs and Carodenuto 2021; Jraisat et al. 2013). Buying firms should at least ensure the availability of transport services for commuting farmers and spacious product delivery trucks to avoid supply delays (Mena et al. 2013; Pancino et al. 2019; Wongprawmas et al. 2015). From a TCE perspective, inadequate infrastructure facilities in a business supply chain increase the transaction costs associated with transportation and coordination (Williamson 2008).

By designing appropriate contracts and monitoring mechanisms through principal-agent relationships from an Agency perspective, buying firms can enhance 'coordination' in a supply chain to mitigate these challenges (Wilhelm et al. 2016). The absence of suppliers' accountability and records of food standards to ensure their reliability and adherence to standards for the buyers also led to operational challenges in the coffee and palm oil sectors of multinationals as well as fruit sectors of Thailand (Grabs and Carodenuto 2021; Wongprawmas et al. 2015). From a social networking perspective, by establishing strong 'collaborative' partnerships and fostering 'information sharing', buying firms can ensure compliance with standards and improve supply chain 'transparency' (Monaghan et al. 2017). The absence of formal and legal contracts resulted in ambiguity and potential 'conflicts', highlighting perspectives of 'conflict theory' (Jraisat et al. 2013; Mirkovski et al. 2015). Failure to publish annual sustainability reports due to suppliers' lack of data provision also reduced buyer data transparency (León Bravo et al. 2021). Community development through social mobilisers can be employed to create decentralised annual sustainability reports. Suppliers can contribute data to designated representatives, ensuring transparency and reliability. These initiatives could mitigate the governance sustainability challenges buying firms face due to a lack of data provision, allowing for a comprehensive and trustworthy source of information for sustainability reporting. However, suppliers should also provide full support to these mobilisers to improve their development and performance (Sjauw-Koen-Fa et al. 2018), and issues with contractors and policy changes disrupted operations and created uncertainty (Jraisat et al. 2013).

The heterogeneity of farm sizes created challenges for buyers in managing and coordinating supply chain activities effectively in Switzerland's fruit juice industry (Grimm et al. 2014). Buyers faced challenges due to their suppliers' poor professional and personal reputations, affecting trust and relationship development in the Brazilian sunflower sector (Grohmann et al. 2023; Sousa et al. 2018). Buying companies need reputable intermediaries to address the challenges emerging from trust issues (Grohmann et al. 2023). Buying firms and intermediaries in 'Principal–Agent' relationships could design contracts and monitoring mechanisms that align the interests of the buyers and suppliers, promoting accountability and ensuring reliable performance (Wilhelm et al. 2016). Due to unknown suppliers in the Chilean raspberries sector, buying firms adopted a spontaneous business approach, lacking focus and organisation, leading to inefficiencies and inconsistencies (Challies and Murray 2011). The spontaneous business approach by the buying firm can be seen as a response to the high 'uncertainty' and 'information asymmetry' associated with dealing with unfamiliar suppliers (Meinlschmidt et al. 2018). In such situations, buying firms face increased transaction costs regarding search and information gathering, negotiating contracts, and monitoring supplier performance (Campos and Mello 2017; Rossi et al. 2023; Weituschat et al. 2023). These transaction costs can hinder the efficiency and effectiveness of the supply chain. The absence of secure storage facilities for chemicals, fertilisers, and equipment posed safety and regulatory concerns (Challies and Murray 2011). Inequitable distribution of resources between upstream and downstream suppliers and lack of understanding about the 'shared needs' created imbalances and dissatisfaction in lower-tier suppliers in the cocoa and chocolate sectors of a Multinational and was constantly reported to buying firms (Blasi et al. 2015; Grabs and Carodenuto 2021; McLoughlin and Meehan 2021; Mirkovski et al. 2015). Challenges due to the packaging and storage of products also forced the buying firms to limit their product delivery planning in Italy's balsamic vinegar and wheat sector (Blasi et al. 2015; León Bravo et al. 2021).

This research reveals that various market dynamics predominantly influenced these sustainability challenges. Considering the overall aspects of the above discussion, a comprehensive governance mechanism is significantly imperative to balance social equity, environmental health, and the economic wealth of multi-tier supply chains (Boström et al. 2015; Chapin et al. 2022; Vasconcelos et al. 2022). However, this undertaking requires sincere relational and organisational embeddedness, collaborative efforts and a holistic approach from all stakeholders to establish a sustainable supply chain structure that should align with the dynamics of the industry and market (Asamoah et al. 2020; Baaken 2022; Broad et al. 2022; Cerdà et al. 2022; DiVito and Ingen-Housz 2021; Ricart and Rico-Amorós 2022; Tanneberger et al. 2022; Vasconcelos et al. 2022). Furthermore, promoting formal, social, and legal contracts in business could also draw clear expectations and obligations between farmers and buyers (Behl et al. 2022; Sheehy 2022). Prior to initiating any business operations, in-depth market research and analysis to understand the characteristics of different sourcing markets could be a practical initial step towards a sustainable business operation (Gabler et al. 2022). As industries evolve and multiple tiers are involved, embracing the above-discussed cutting-edge analytical approaches becomes imperative for creating resilient and sustainable supply chain ecosystems for buying firms.

Conclusion and future research directions

Investigating the crop agri-food sector, the systematic review established that lower-tier suppliers and buying firms faced numerous sustainability challenges across economic, environmental, social, and governance sustainability dimensions. The analysis of these challenges underscored a pervasive issue—the absence of a robust integration link between buyers and their lower-tier raw material suppliers. This missing link, attributed to the cross-border nature and diverse geographical locations of the supply chain tiers, was rooted further in two primary factors. First, buying firms were found to lack an effective governance structure within their multi-tier supply chains, rendering them inadequately prepared to address sustainability challenges in cross-border contexts. This inadequacy perpetuated challenges and hindered the establishment of cohesive sustainability practices. Secondly, the prevalent practices of contractual relationships, primarily only with first-tier suppliers, contributed to the multidimensional sustainability challenges. Suppliers beyond tier-one in this contractual relationship were consequently overlooked, resulting in a cascade of ignored sustainability challenges throughout the supply chain.

Despite the study's contribution, it also has some limitations; primarily, the reliance on a limited number of databases in this review may not entirely capture all studies potentially relevant to the scope of the research. The exclusive focus on journal articles inadvertently excludes other equally important knowledge sources such as books, chapters, and conference papers, potentially limiting the comprehensive investigation of the subject matter. Moreover, the review's findings were guided by the set of keywords used by the authors, and also the selections of the methods of the studies may have some potential biases. In particular, the review is limited to phenomenological and interpretive qualitative paradigms; however, a broader framework of the multifaceted sustainability challenges could be achieved by including positivist research paradigms for the crop agri-food sector.

The study's findings establish a theoretical framework for understanding sustainability challenges in diverse sectors and geographies of the crop agri-food sector. This theoretical framework could guide further research into the subject matter using ethnographies, longitudinal studies, or action research, especially in agri-based economies. These methods can potentially uncover overlooked sustainability challenges among supply chain actors, offering actionable insights for practical application. Furthermore, the findings support establishing a collaborative business structure involving all stakeholders and utilising various intermediaries beyond tier-one suppliers, considering them strategic business partners rather than commodities in multi-tier supply chains.

The descriptive analysis of the review also sets unique theoretical directions for scholars. In future research, integrating social network theory's ‘relational’ and ‘structural embeddedness’ aspects with the physical and tangible attributes of the resource-based view could provide distinctive perspectives. For example, in collectivistic societies, relational embeddedness often leads to structural embeddedness in businesses. Considering this within the resource-based view context in developing countries, where resources are mainly generated, may offer a unique approach to supply chain theory. The practical implementations propose that businesses should emphasise capitalising on internal resources sourced from raw material production sites, thereby reducing reliance on external market factors to foster sustainable development objectives.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

EbscoHost, Emerald, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, and Wiley Online.

Population (s) Buying companies (food companies sourcing through cross-border multi-tier supply chain). Intervention (s) Sustainable Governance structures (direct, indirect, through third parties and don’t bother). Comparator (s) could be any relevant, e.g. buying company or unit of analysis. Outcome(s) Sustainability challenges (economic, social, environmental and governance).

Sustainab* OR standards OR environment* OR economic OR social OR governance or supply chain structure OR Crop agri-Food OR fruit OR vegetable OR coffee OR edible* Buy* company* OR global OR cross-borders OR Agri* AND Multitier OR long supply chain OR complex supply chain*

Web of Science and Scopus-indexed studies were considered available in Harper Adams University’s electronic research databases.

Studies focused on the ‘crop agri-food sector’ and ‘sustainable multi-tier business supply chain structures’. Studies from the ‘same authors’ but from different perspectives (different food supply chains, etc.) also ‘highlight sustainability challenges for the lower-tier suppliers and the buying firms’. Studies discussing ‘managing strategies of the buying firms to address sustainability challenges’.

References

Alsayegh MF, Rahman RA, Homayoun S (2020) Corporate economic, environmental, and social sustainability performance transformation through ESG disclosure. Sustainability 12:3910. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093910

Ardoin NM, Bowers AW, Wheaton M (2023) Leveraging collective action and environmental literacy to address complex sustainability challenges. Ambio 52:30–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-022-01764-6

Asamoah D, Agyei-Owusu B, Ashun E (2020) Social network relationship, supply chain resilience and customer-oriented performance of small and medium enterprises in a developing economy. Benchmark Int J 27(5):1793–1813. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-08-2019-0374

Baaken MC (2022) Sustainability of agricultural practices in Germany: a literature review along multiple environmental domains. Reg Environ Change 22:39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-022-01892-5

Bashir R, Surian D, Dunn AG (2018) Time-to-update of systematic reviews relative to the availability of new evidence. Syst Rev 7:195. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0856-9

Behl A, Kumari PSR, Makhija H, Sharma D (2022) Exploring the relationship of ESG score and firm value using cross-lagged panel analyses: case of the Indian energy sector. Ann Oper Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-04189-8

Blasi C, Monotti L, Ruini C, Landi GA, Meriggi P (2015) Eco-innovation as a driver in the agri-food value chain: an empirical study on durum wheat in Italy. J Chain Netw Sci 15(1):1–15

Blome C, Schoenherr T, Eckstein D (2014) The impact of knowledge transfer and complexity on supply chain flexibility: a knowledge-based view. Int J Prod Econ 147:307–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2013.02.028

Booth A (2016) Searching for qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a structured methodological review. Syst Rev 5(1):1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0249-x

Boström M, Jönsson AM, Lockie S, Mol APJ, Oosterveer P (2015) Sustainable and responsible supply chain governance: challenges and opportunities. J Clean Prod 107:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.11.050

Bradford M, Taylor EZ, Seymore M (2022) A view from the CISO: insights from the data classification process. J Inf Syst 36(1):201–218. https://doi.org/10.2308/ISYS-2020-054

Brandli LL, Salvia AL, Dal Moro L (2022) Editorial: the contribution of sustainable production and consumption to a green economy. Discov Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-022-00098-3

Brennan M, Hennessy T, Dillon E, Meredith D (2023) Putting social into agricultural sustainability: integrating assessments of quality of life and wellbeing into farm sustainability indicators. Sociol Rural 63(3):629–660

Broad GM, Marschall W, Ezzeddine M (2022) Perceptions of high-tech controlled environment agriculture among local food consumers: using interviews to explore sense-making and connections to good food. Agric Hum Values 39(3):417–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10261-7

Bryman A, Bell E (2011) Business research methods, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press Inc., New York

Bush SR, Oosterveer P, Bailey M, Mol APJ (2015) Sustainability governance of chains and networks: a review and future outlook. J Clean Prod 107:8–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.10.019

Campos JGFD, Mello AMD (2017) Transaction costs in environmental purchasing: analysis through two case studies. J Oper Supply Chain Manag 10(1):87. https://doi.org/10.12660/joscmv10n1p87-102

Canto NR, Bossle MB, Vieira LM, De Barcellos MD (2021) Supply chain collaboration for sustainability: a qualitative investigation of food supply chains in Brazil. Manag Environ Qual Int J 32(6):1210–1232. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-12-2019-0275

Cerdà A, Franch-Pardo I, Novara A, Sannigrahi S, Rodrigo-Comino J (2022) Examining the effectiveness of catch crops as a nature-based solution to mitigate surface soil and water losses as an environmental regional concern. Earth Syst Environ 6:29–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-021-00284-9

Chacón Vargas JR, Moreno Mantilla CE, de Sousa Jabbour ABL (2018) Enablers of sustainable supply chain management and its effect on competitive advantage in the Colombian context. Resour Conserv Recycl 139:237–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.08.018

Challies ERT, Murray WE (2011) The interaction of global value chains and rural livelihoods: the case of smallholder raspberry growers in Chile. J Agrar Change 11(1):29–59

Chapin FS, Weber EU, Bennett EM, Biggs R, van den Bergh J, Adger WN, de Zeeuw A (2022) Earth stewardship: Shaping a sustainable future through interacting policy and norm shifts. Ambio 51:1907–1920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-022-01721-3

Choi TY, Dooley KJ, Rungtusanatham M (2001) Supply networks and complex adaptive systems: control versus emergence. J Oper Manag 19(3):351–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(00)00068-1

Cohen J (1960) A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Measur 20(1):37–46

Davis GF, Cobb JA (2010) Chapter 2: resource dependence theory: past and future. Res Sociol Organ 28:21–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/s0733-558x(2010)0000028006

Degli Innocenti E, Oosterveer P (2020) Opportunities and bottlenecks for upstream learning within RSPO certified palm oil value chains: a comparative analysis between Indonesia and Thailand. J Rural Stud 78:426–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.07.00

Derqui B (2020) Towards sustainable development: evolution of corporate sustainability in multinational firms. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 27(6):2712–2723. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1995

Desiderio E, García-Herrero L, Hall D, Segrè A, Vittuari M (2022) Social sustainability tools and indicators for the food supply chain: a systematic literature review. Sustain Prod Consum 30:527–540

de Sousa LO, Ferreira MDP, Mergenthaler M (2018) Agri-food chain establishment as a means to increase sustainability in food systems: lessons from sunflower in Brazil. Sustainability 10:2215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072215

DiVito L, Ingen-Housz Z (2021) From individual sustainability orientations to collective sustainability innovation and sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Bus Econ 56(3):1057–1072

Doyle L, Brady A-M, Byrne G (2009) An overview of mixed methods research. J Res Nurs 14(2):175–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987108093962