Abstract

Background

Antibiotic prescribing is common worldwide. There are several original studies about antibiotic prescribing in the healthcare setting of Iran reporting different levels of prescribing. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the prevalence of antibiotic prescribing in both inpatient and outpatient settings in Iran, an example of a developing country.

Methods

To identify published studies on antibiotic prescribing, databases such as ISI, Scopus, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Electronic Persian were searched in Iran till January 2020. Eligible studies were those analyzing original data on the prescription and use of antibiotics in outpatient or inpatient settings in Iran. Moreover, all studies that used an intervention to improve antibiotic prescribing were included. The quality of the included studies was assessed using self-administered quality assessment criteria. The meta-analysis of prevalence of antibiotic prescribing was conducted based on the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology guidelines. To calculate pooled rates, the random-effects model was used.

Results

A total of 54 studies (39 outpatients and 15 inpatients) were included in this study. The median of antibiotic prescribing in the outpatient and inpatient settings accounted for 45.25% and 68.2% of patients, respectively. The results of meta-analysis also showed that the antibiotic prescribing accounted for 45% of prescriptions in outpatient settings and 39.5%, 66%, and 75.3% of patients in all wards, pediatrics wards, and ICU wards of inpatient settings, respectively. The most commonly prescribed antibiotic classes in outpatient settings were penicillins, cephalosporins, and macrolides, while in inpatient settings, these were cephalosporins, penicillins, and carbapenems. There were seven studies using interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing pattern. It should be mentioned that intervention in a study had a statistically significant effect on improving antibiotic prescribing (p < .05).

Conclusion

Prevalence of antibiotic prescribing in Iran is high. Our findings highlight the need for urgent action to improve prescription practices. It seems that developing a national plan to improve antibiotic prescribing is necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Prescribing and use of antibiotics have spread worldwide. These medications are among the most frequently used and expensive drugs for patients as well as health care organizations [1]. Although the use of antibiotics is helpful in the treatment of patients, their irrational, excessive use has become a major concern; therefore, it has led to the spread of antibiotic resistance, one of the greatest threats to human health. Antibiotic resistance may lead to delay in providing effective care, increased costs, and even death [2,3,4,5]. One of the most important reasons for antibiotic resistance is inappropriate, excessive use of antibiotics [6, 7].

Monitoring the patterns and rates of antibiotic prescribing are among the recommended strategies to prevent their overuse [8]. In addition, determining the prevalence of antibiotic prescribing is one of the main criteria in evaluating the antibiotics status [9]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the ideal prevalence for antibiotic prescribing is 20–26.8% of prescriptions [1, 11]. The antibiotic prescribing rate is increasing and often exceeds the WHO recommendation threshold in various developed and developing countries such as USA, many European countries (such as France, Spain, Portugal, Cyprus, Iceland, Greece, and Czech Republic), Asian, and African countries (such as China, Thailand, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Egypt) [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

Many studies estimated the rate of antibiotic prescribing in inpatient and outpatient settings in different countries and reported different estimates [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. However, there are few studies that have systematically reviewed the rate of antibiotic prescribing worldwide [18, 26, 27]. The results of two systematic review and meta-analysis studies in China showed that the overall rate of antibiotic prescribing in healthcare settings and in patients with upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) was high [18, 26]. The results of another one revealed that the rate of antibiotic prescribing in pediatrics hospitals in countries with poor resources was high [27]. Antibiotic usage is high in Iran which is a developing country. Some studies reported antibiotic prescribing prevalence of 45–72% in inpatients and outpatients in this country [28,29,30]. Several studies have been conducted to evaluate the rate of antibiotic prescribing in different geographical areas, healthcare settings, and even in a number of patients [30, 33,34,35,36] and each of which reported different rates. Therefore, it is important to perform a systematic review studies appear to be helpful in planning and controlling the use and prescription of these medications by providing a summary of the evidence and an overview of antibiotic prescribing in healthcare settings. This supports decision making pertaining to health about antibiotic prescribing. Thus, this systematic review and meta-analysis study aimed at determining the prevalence of antibiotic prescribing in different settings in Iran.

Methods

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed using terms and MeSH terms related to antibiotic (e.g. antibiotic, anti-infective agents, antimicrobial, and antibacterial), prescribing (e.g. prescription, prescribe, administer, dispense, consumption, therapy, and Treat), and Iran (e.g. Iran, Iranian, Farsi, Persian).

Electronic databases (i.e. ISI, Scopus, and MEDLINE/PubMed) were searched using customized search strategies on Jan 2020. Persian electronic databases, including MagIran and SID (Scientific Information Database), were searched using Persian terms which are similar to the above-mentioned ones. Google Scholar was also searched using Persian search terms, to avoid missing relevant papers. Finally, the list of references in all retrieved papers was reviewed to identify extra relevant studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The original studies included were those investigating antibiotic prescribing rate in patients’ prescriptions or hospital patients’ records, those using an intervention to improve antibiotic prescribing pattern and the ones conducted in either inpatient or outpatient settings in Iran and published in Persian or English. Due to the necessity of prescribing antibiotics in surgery, dentistry, and burn patients, the studies on these populations were not included. In addition, conference papers, letters, opinions, and dissertations were also excluded.

Review procedure and data extraction

One of the reviewers searched the databases (R.A). Screening the title and abstract of potentially relevant papers were carried out by two independent reviewers (E.N, R.A). Any potential conflict about the inclusion of papers was discussed by them and after reaching a consensus, they made an appropriate decision. Subsequently, the full text of the included papers was retrieved to fulfil the aims of this review, and if not available, the full-texts were requested from the authors via email.

After reviewing the full-text for each included paper, the following information was extracted: authors, year of study, region, setting, sample size, unit of analysis, percentage of antibiotic prescribing (per prescription or medical record), the number of antibiotics in each prescription (one, two, and more than two antibiotics), and antibiotic classes and names. In the case of interventional studies, in addition to the above mentioned information, the type of study, the type of intervention used, and its effects were also extracted. Since patients’ age and gender, type of disease, type of insurance, and type of cost payment have not been investigated in most of the included studies, we could not consider this type of data in our analysis.

Quality assessment of the included studies

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated by a self-administered checklist based on related studies [18, 37] and approved by three specialists (Pharmacology, medical informatics, and health information management) (Table 1).

Total quality scores ranged from 0 to 10 (0–4 points = poor, 5–7 points = moderate, 8–10 points = high). Two independent reviewers scored the quality of each study according to the mentioned criteria and the third reviewer resolved potential discrepancies.

Statistical analysis

The median and interquartile range (IQR) of antibiotic prescribing rates were calculated. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on the healthcare setting type (inpatient and outpatient). To standardize the meta-analysis methodology, the rates of antibiotic prescribing were obtained. Data were analyzed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) software (Version 2.0). The meta-analysis was conducted based on the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology guidelines [38]. Interventional studies were excluded for meta-analysis. Pooled rates were calculated with a 95% confidence interval (CI) using a random-effects model. For publication bias, Egger’s weighted regression method was used.

Results

Literature search results

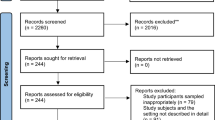

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the literature search. The electronic literature search led to the identification of 5868 published papers. After excluding duplicates, 4699 unique papers remained. After reviewing the titles of the papers as well as their abstracts and also considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 80 papers were selected for full-text review. Furthermore, by hand-searching in Google Scholar and the reference lists of the included papers, 7 additional related papers were identified. After a detailed full-text review of 87 papers, 33 papers were excluded because they reported antibiotic prescribing based on the defined daily dose (DDD), defined daily dose per 100 Inhabitants per day (DID), or defined daily dose per bed day (DBD) scales [33, 35, 39,40,41,42], or only assessed prescriptions containing antibiotics and did not report the ratio of antibiotic-containing prescriptions to all prescriptions [43, 44]. Finally, a total of 54 papers were selected to be included in this study.

General characteristics of the included studies

The included studies were conducted from 1995 to 2016. In total, 39 (72%) studies were conducted in outpatient settings and 15 (28%) in inpatient settings. Out of 39 studies in outpatient settings, 7 (18%) studies evaluated the effects of interventions on antibiotic prescription [45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

Quality of the included studies

The quality assessment of the included studies showed that none of them fulfilled all the quality criteria. Twelve (22%) studies were of high quality, 35 (65%) were of moderate quality, and 7 (13%) were of poor quality. Only 18 studies (33%) listing their limitations.

Findings obtained from the interventional studies

All of the interventional studies were conducted in outpatient settings during 1995–2012. Since there was difference in the percentage of antibiotic prescribing in before and after of interventions, the results of interventional studies were reported separately from other outpatient studies (Table 2). All the interventions were educational [45,46,47,48,49], and in two studies [50, 51], both feedback and educational materials were used. The interventions used in these studies resulted in a relative improvement in antibiotic prescribing pattern; however, in one study, the effect of intervention was statistically significant (p < 0.05) [45].

The prevalence of antibiotic prescription in inpatient healthcare settings

Among the reviewed studies, 15 (28%) ones were done in inpatient settings during 1997–2014. In two studies (13%) [52, 53], the unit of analysis was the prescriptions. In the other 13 studies (87%), the unit of analysis was patients or hospital patients' records, which were considered to be equal. Also, 3, 4, and 4 studies were done in all wards, pediatrics wards, and ICU wards, respectively. The minimum and maximum sample sizes were 104 and 17,668 patients, respectively. Most of the studies (80%) did not report the most commonly prescribed antibiotic classes. The median of antibiotic prescribing in inpatient setting accounted for 68.2% of patients. Cephalosporins, carbapenems, and penicillins were the most commonly prescribed antibiotic classes. Ceftriaxone, cefazolin, vancomycin, and clindamycin were the most commonly prescribed antibiotics (Table 3). Due to difference in the various inpatient settings (i.e. all wards, pediatrics, ICU, and emergency), the total meta-analysis was not performed but just conducted separately on similar settings. The meta-analysis results showed that in the studies pertaining to all wards, pediatrics wards, and ICU wards, antibiotics were prescribed for 39.5, 66, and 75.3% of patients, respectively (Additional file 1: Attachments).

The prevalence of antibiotic prescription in outpatient healthcare settings

Among the reviewed studies, 32 (59%) ones were conducted in outpatient settings during 1995–2019. In these studies, the unit of analysis was either prescriptions or patients, and the minimum and maximum sample sizes were 441 and 200,000,000, respectively. Most of the studies (75%) did not report the most commonly prescribed antibiotic classes. Penicillin, cephalosporin, macrolides, as well as aminoglycosides were the most commonly prescribed antibiotic classes. Amoxicillin, penicillin, co-amoxiclav, and cefixime were the most frequently prescribed antibiotics (Table 4). Figure 2 shows the meta-analysis results and the percentages of prescribed antibiotics extracted from 27 studies conducted in outpatient settings. The total mean of antibiotic-containing prescriptions was 45% and their median in outpatient settings was 45.25%.

NM: Not Mentioned.

Discussion

This study aimed at providing an overview of the antibiotic prescribing pattern in Iran, as an example of developing countries. The results of this study showed that the rate of antibiotic prescribing in inpatient and outpatient settings in Iran was 68.2% for patients and 45.25% for prescriptions, respectively. Cephalosporins and carbapenems were the most commonly prescribed antibiotic classes in inpatient settings, while in outpatient settings, they were penicillins, cephalosporins, and macrolides.

Due to overprescribing of antibiotics in Iran, there are few studies using interventions to improve the pattern of antibiotic prescribing. Although there are different potential interventions pertaining to rational antibiotic prescribing, almost all the studies conducted in Iran have used educational interventions for physicians. Many of these interventions had no statistically significant effect on improving antibiotic prescribing pattern. It seems, nowadays, these traditional interventions have little effectiveness rather than electronic interventions. It is predicted that IT-based interventions with the provision of some capabilities such as regularly and automated registration of medications, performance feedback, and a reminder to physicians, and easy access to information at the point of care can help to more rational prescribing medications. Some of the studies [93,94,95,96] have shown that IT-based interventions (such as clinical decision support systems (CDSSs), electronic health record (EHR), electronic prescribing, and electronic based feedback on physician’s performance) could improve antibiotic prescribing pattern. Studying IT-based interventions and their effects merits further research.

We found that more than two-thirds of patients received antibiotics in the inpatient settings in Iran (median = 68.2%). The results of a global study showed that antibiotic consumption increased by 65% in 76 countries from 2000 to 2015 (from 21.1 to 34.8 billion DDDs) [97]. The experts from the center for disease control and prevention found that the total rate of antibiotic use in the United States hospitals did not change from 2006–2012, and that more than half of the patients received at least one antibiotic during their hospital stay [98]. The rate of antibiotic prescribing in Iran (68.2%) is similar to that reported in an original study in Nigeria (69.7%) and surpassed the WHO recommended range of 20–26.8% and in some developed countries such as Italy. Moreover, the rate of antibiotic prescribing in Iran is less than that in some developing countries such as Turkey, India, China, Tunisia, and Greece [97, 99]. Thus, since the antibiotic prescribing rate is high in the inpatient settings in Iran, applying interventions to improve that is necessary.

The results of this study showed that nearly half of the outpatients received antibiotics in Iran (median = 45.25% and meta-analysis = 45%). The results of a study by Yin et al. [18] showed that antibiotic prescribing in outpatient centers in China was 50.3%, and almost more than half of the outpatient visits in China resulted in prescribing antibiotics. In addition, Li et al. [26] reported the rate of antibiotic prescribing at URTI outpatient centers in China as 83.7%. The antibiotic prescribing rate is high in the United States as well, and almost 269 million antibiotic prescriptions were dispensed from outpatient pharmacies in 2015. Moreover, 5 out of 6 Americans received an antibiotic prescription in that year [75]. Another study in the United States showed that the mean of antibiotic prescribing per 1,000 patients was 826 cases in 2013 and 2015 in outpatients [100]. The overall rate of antibiotic prescribing in Iranian outpatient settings was higher than in many other undeveloped countries such as Maldives (24%), Bangladesh (31%), DPR Korea (35%), Cameroon (36.71%), Bhutan (41%), and East Timor (43%), but similar to Nepal (44%) and Indonesia (45%), and less than in Myanmar (47%), Sri Lanka (56%), India (62%), and Jordan (78%) in Africa, the Middle East, and East Asia [15, 16, 101]. Since the antibiotic prescribing rate is high in outpatients in Iran, interventions to reduce antibiotic prescribing rate is necessary. While educational interventions had no significant effect on reducing antibiotic prescribing rate in this country, the use of new interventional methods is suggested.

The most common antibiotic classes prescribed in inpatient settings were cephalosporins, penicillins, and carbapenems, while in outpatient settings, they were penicillins, cephalosporins, and macrolides. Furthermore, the most frequently prescribed antibiotics were ceftriaxone and cefazolin in inpatient settings and amoxicillin, penicillin, co-amoxiclav, and cefixime in outpatient settings. Antibiotics classes such as penicillins, cephalosporins, quinolones, and macrolides were the most common antibiotic classes consumed in 76 countries during 2000–2015 [97]. Although consumption of broad-spectrum penicillins, carbapenems, and polymyxins has increased in high, middle, and low-income countries, there are some differences in the consumption of antibiotic classes. For example, cephalosporins consumption has increased in low and middle income countries, while it has declined in high income countries [97]. Also, in outpatient settings in the USA, the most commonly prescribed antibiotics in 2018 were azithromycin, amoxicillin, ciprofloxacin, and cephalexin [100]. Some of the most prescribed antibiotics in this study such as amoxicillin and cefazoline were placed in the access group and cefexime, ceftriaxone and vancomycin were placed in the watch group based on Access, Watch, Reserve (AWaRe) classification of antibiotics by WHO [102]. Despite the high use of some antibiotic classes such as carbapenems, quinolones, and cephalosporins, particularly the third generation of broad-spectrum antibiotics, they should be used with caution. These antibiotic classes have a high potential to cause antimicrobial resistance or side effects; however, their consumption has increased rapidly in low and middle income countries, while it has decreased in high income countries. [97, 103]. Thus, based on the obtained results, it seems necessary to change the antibiotic consumption patterns in Iran.

Implications

Our results may help increase the awareness and knowledge about the antimicrobials use and identifying areas of overuse in this country. Moreover, Iranian health policymakers could develop a national plan to improve the clinical application of antibiotics and consider use of recommended IT-based interventions.

Strength and limitations

This study is the first to describe the prevalence of antibiotic prescriptions in Iran. It also provides an overview of interventions taken to improve antibiotic prescriptions in this country. However, the Persian search engine is limited but we conducted several search strategies such as searching Google Scholar, hand-searching, and searching reference lists of the included studies. We did exclude different kind of studies: studies describing antibiotic prescribing in surgery, dentistry, and burn patients (because of the necessity of antibiotics); studies that reported antibiotic prescription without the frequencies that we sought (because they reported DDD, DID, DBD scales); and studies that assessed only special classes of antibiotics such as vancomycin, imipenem, aminoglycosides, meropenem, ciprofloxacin (because they do not provide a comprehensive picture of antibiotic prescribing).

Conclusion

This study showed that antibiotic prescribing rate in both inpatient and outpatient settings in Iran surpasses the WHO recommendations and exceeds that in many other countries. Moreover, this study revealed that traditional educational interventions showed no significant effect on reducing antibiotic prescribing rate. In order to decrease antibiotic prescribing by physicians, IT-based interventions such as electronic feedback on physicians’ performance, electronic prescribing, and clinical decision support systems may hold promise.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yimenu DK, Emam A, Elemineh E, Atalay W. Assessment of antibiotic prescribing patterns at outpatient pharmacy using world health organization prescribing indicators. J Primary Care Commun Health. 2019;10:2150132719886942.

Eliopoulos GM, Cosgrove SE, Carmeli Y. The impact of antimicrobial resistance on health and economic outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(11):1433–7.

Kumar R, Indira K, Rizvi A, Rizvi T, Jeyaseelan L. Antibiotic prescribing practices in primary and secondary health care facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;33(6):625–34.

Seppala H, Klaukka T, Vuopio-varkila J, Muotiala A, Helenius H, Lager K, et al. The effect of changes in the consumption of macrolide antibiotics on erythromycin resistance in group A streptococci in Finland. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(7):441–6.

van Bijnen EM, den Heijer CD, Paget WJ, Stobberingh EE, Verheij RA, Bruggeman CA, et al. The appropriateness of prescribing antibiotics in the community in Europe: study design. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):293.

Abdulah R. Antibiotic abuse in developing countries. Pharm Regul Aff. 2012;1(2):1000e106.

Arason VA, Sigurdsson JA, Erlendsdottir H, Gudmundsson S, Kristinsson KG. The role of antimicrobial use in the epidemiology of resistant pneumococci: a 10-year follow up. Microbial drug Resist. 2006;12(3):169–76.

Krivoy N, El-Ahal WA, Bar-Lavie Y, Haddad S. Antibiotic prescription and cost patterns in a general intensive care unit. Pharmacy Pract. 2007;5(2):67–73.

Organization WH. Using indicators to measure country pharmaceutical situations: fact book on WHO level I and level II monitoring indicators. Using indicators to measure country pharmaceutical situations: fact book on WHO level I and level II monitoring indicators; 2006.

World Health Organization. Action Programme on Essential D, Vaccines. How to investigate drug use in health facilities : selected drug use indicators. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993.

Antibiotic Use in the United States, 2017: Progress and Opportunities: Antibiotic Use By Healthcare Setting: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/stewardship-report/outpatient.html.

Prevention CfDCa. “Outpatient Antibiotic Prescriptions—United States" 2015. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/pdfs/Annual-report-2015.pdf.

Trends in U.S. Antibiotic Use 2018. Available from: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2018/08/trends-in-us-antibiotic-use-2018.

Initiative AEH. Summary of the latest data on antibiotic consumption in the European Union. European center for disease prevention and control; 2017.

Holloway KA, Kotwani A, Batmanabane G, Puri M, Tisocki K. Antibiotic use in South East Asia and policies to promote appropriate use: reports from country situational analyses. BMJ. 2017;358:j2291.

Ababneh MA, Al-Azzam SI, Ababneh R, Rababa’h AM, Demour SA. Antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections in children in Jordan. Int Health. 2017;9(2):124–30.

Alnemri AR, Almaghrabi RH, Alonazi N, Alfrayh AR. Misuse of antibiotic: a systemic review of Saudi published studies. Curr Pediatric Res. 2016.

Yin X, Song F, Gong Y, Tu X, Wang Y, Cao S, et al. A systematic review of antibiotic utilization in China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(11):2445–52.

[Antibiotic prescription in odontology and stomatology: recommendations and indications]. Revue de stomatologie et de chirurgie maxillo-faciale. 2002;103(6):352–68.

Denes E, Prouzergue J, Ducroix-Roubertou S, Aupetit C, Weinbreck P. Antibiotic prescription by general practitioners for urinary tract infections in outpatients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31(11):3079–83.

Love BL, Mann JR, Hardin JW, Lu ZK, Cox C, Amrol DJ. Antibiotic prescription and food allergy in young children. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2016;12:41.

Erlandsson M, Burman LG, Cars O, Gill H, Nilsson LE, Walther SM, et al. Prescription of antibiotic agents in Swedish intensive care units is empiric and precise. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007;39(1):63–9.

Venmans LM, Hak E, Gorter KJ, Rutten GE. Incidence and antibiotic prescription rates for common infections in patients with diabetes in primary care over the years 1995 to 2003. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(6):e344–51.

Grijalva CG, Nuorti JP, Griffin MR. Antibiotic prescription rates for acute respiratory tract infections in US ambulatory settings. JAMA. 2009;302(7):758–66.

Mihani J, Kellici S. Patterns of antibiotic prescription in children: Tirana, Albania Region. Open Access Macedonian J Med Sci. 2018;6(4):719–22.

Li J, Song X, Yang T, Chen Y, Gong Y, Yin X, et al. A systematic review of antibiotic prescription associated with upper respiratory tract infections in China. Medicine. 2016;95:19.

Irwin A, Sharland M. Measuring antibiotic prescribing in hospitalised children in resource-poor countries: a systematic review. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49(3):185–92.

Karimi A, Haerizadeh M, Soleymani F, Haerizadeh M, Taheri F. Evaluation of medicine prescription pattern using World Health Organization prescribing indicators in Iran: a cross-sectional study. J Res Pharmacy Pract. 2014;3(2):39.

Cheraghali AM, Nikfar S, Behmanesh Y, Rahimi V, Habibipour F, Tirdad R, et al. Evaluation of availability, accessibility and prescribing pattern of medicines in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern Mediterranean health journal = La revue de sante de la Mediterranee orientale = al-Majallah al-sihhiyah li-sharq al-mutawassit. 2004;10(3):406–15.

Fahimzad A, Eydian Z, Karimi A, Shiva F, Armin S, Ghanaei RM, et al. Antibiotic prescribing pattern in neonates of seventeen Iranian hospitals. Arch Pediatr Infect Dis. 2017;5:4.

Fahimzad A, Eydian Z, Karimi A, Shiva F, Sayyahfar S, Kahbazi M, et al. Surveillance of antibiotic consumption point prevalence survey 2014: antimicrobial prescribing in pediatrics wards of 16 Iranian hospitals. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19(3):204–9.

Mostafavi N, Rashidian A, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, Khosravi A, Kelishadi R. The rate of antibiotic utilization in Iranian under 5-year-old children with acute respiratory tract illness: a nationwide community-based study. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20(5):429–33.

Ebrahimzadeh MA, Shokrzadeh M, Ramezani A. Utilization pattern of antibiotics in different wards of specialized sari Emam University Hospital in Iran. Pak J Biol Sci. 2008;11(2):275–9.

Hosseinzadeh F, Sadeghieh Ahari S, Mohammadian-erdi A. Survey the antibiotics prescription by general practitioners for outpatients in Ardabil City in 2013. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci. 2016;16(2):140–50.

Noubarani M, Shafizade F, Hajikarim B. Antibiotic prescription pattern in Vali-Asr hospital units of Zanjan City. J Zanjan Univ Med Sci Health Serv. 2016;24(106):122–9.

Taghizadeh S, Haghdoost M, Mashrabi O, Zeynalikhasraghi Z. Antibiotic usage in intensive care units of Tabriz Imam Reza hospital, 2011. Am J Infect Dis. 2013;9(4):123–8.

Nabovati E, Vakili-Arki H, Taherzadeh Z, Hasibian MR, Abu-Hanna A, Eslami S. Drug-drug interactions in inpatient and outpatient settings in Iran: a systematic review of the literature. DARU J Pharm Sci. 2014;22(1):52.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Salehifar E, Nasehi M, Eslami G, Sahraei S, Navaei RA. Determination of antibiotics consumption in Buali-Sina Pediatric Hospital, Sari 2010–2011. Iran J Pharm Res. 2014;13(3):995–1001.

Ansari F. Utilization review of systemic antiinfective agents in a teaching hospital in Tehran, Iran. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57(5–6):541–6.

Ansari F. Use of systemic anti-infective agents in Iran during 1997–1998. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57(6–7):547–51.

Abbasian H, Hajimolaali M, Yektadoost A, Zartab S. Antibiotic utilization in Iran 2000–2016: Pattern analysis and benchmarking with organization for economic co-operation and development Countries. J Res Pharm Pract. 2019;8(3):162–7.

Mohammadi M, Etminani K, Chaboki B, Kermani FS. Study of the antibiotics use patterns in inpatients of trauma centers in Iran during 2014–2015. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2019;13(2):261–7.

Hashemi S, Nasrollah A, Rajabi M. Irrational antibiotic prescribing: a local issue or global concern? EXCLI J. 2013;12:384–95.

Mohagheghi MA, Mosavi-Jarrahi A, Khatemi-Moghaddam M, Afhami S, Khodai S, Azemoodeh O. Community-based outpatient practice of antibiotics use in Tehran. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(2):135–8.

Zare N, Razmjou MM, Ghaeminia M, Zeyghami B, Agha-Maleki Z. Effectiveness of the feedback and recalling education on quality of prescription by general practitioners in Shiraz. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2008;9(4):255.

Garjani A, Salimnejad M, Shamsmohamadi M, Baghchevan V, Vahidi RG, Maleki-Dijazi N, et al. Effect of interactive group discussion among physicians to promote rational prescribing. Eastern Mediterranean health journal = La revue de sante de la Mediterranee orientale = al-Majallah al-sihhiyah li-sharq al-mutawassit. 2009;15(2):408–15.

Ataei M, Rahimi W, Rezaei M, Koohboomi J, Zobeiri M. The effect of antibiotics rational use workshop on prescription pattern of General Physicians in Kermanshah. J Kermansha Univ Med Sci. 2010;14(1):1–9.

Esmaily HM, Silver I, Shiva S, Gargani A, Maleki-Dizaji N, Al-Maniri A, et al. Can rational prescribing be improved by an outcome-based educational approach? A randomized trial completed in Iran. J Continuing Educ Health Prof. 2010;30(1):11–8.

Sadeghi Sedeh B, Rabiei Z, Razavi H. Effects of health belief model components in general physicion rational prescribing of Chaharmahal va Bakhtiary province. Razi J Med Sci. 2015;21(128):37–46.

Soleymani F, Rashidian A, Hosseini M, Dinarvand R, Kebriaeezade A, Abdollahi M. Effectiveness of audit and feedback in addressing over prescribing of antibiotics and injectable medicines in a middle-income country: an RCT. Daru. 2019;27(1):101–9.

Cheraghali AM, Panahi Y, Alidadi A. Evaluation of physicians’ prescriptions in hospitals affiliated to a medical science university in Tehran. TEB VA TAZKIEH. 1997;44:30–6.

Shayan Z, Shayan F. Pattern of drug prescription in clinical ward of motahari and peimanie hospital in khordad 1385. J Jahrom Univ Med Sci. 2006;5:5.

Hajebi G, Mortazavi A, Goudarzi J. A survey of consumption pattern of antibiotics in Taleghani Hospital. Pejouhesh dar Pezeshki (Res Med). 2005;29(2):157–64.

Tavallaee M, Fahimi F, Kiani S. Drug-use patterns in an intensive care unit of a hospital in Iran: an observational prospective study. Int J Pharm Pract. 2010;18(6):370–6.

Khodabakhshi B. Pattern of Antibiotics Prescription in a Referral Academic Hospital, Northeast of Iran. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3982357/.

Khakshour A, Taherpour M, Khorashadizadeh F, Madadi I. Frequency of inappropriate administration of antibiotics in pediatric gastroenteritis in Imam Reza Hospital in Bojnourd in 2010. J Khorasan Shomali Univ Med Sci. 2013;3:2.

Alavi SM, Roozbeh F, Behmanesh F. Pattern of antibiotic usage in Razi hospital in Ahvaz, Iran (2011–12). J Gorgan Univ Med Sci. 2014;16(2):107–13.

Rafati MR, Sahraei S, Zamani Z. Antibiotics usage in intensive care unit in sari bouali sina hospital. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci (JMUMS). 2015;25:122.

Abbasi E, Nasimfar A, Gazzavi A, Karamiyar M, Nikibakhsh AA, Mahmodzadeh H, et al. Evaluation of antibiotic utilization pattern for non-bacterial gastroenteritis in patients hospitalized at Motahari hospital: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Urmia Med J. 2019;29(12):881–6.

Reihani H, Nader H, Mehramiz NJ, Rezaiyan MK, Foroughian M. Antibiotic prescription patterns in an academic emergency department in Iran. World Family Med. 2018;16(3):24–9.

Sabour M, Foroughan M, Mohammadi F. Prescription pattern of medication in the elderly residing in nursing homes in Tehran. Medicinski glasnik Specijalne bolnice za bolesti štitaste žlezde i bolesti metabolizma’Zlatibor’. 2014;19(51):23–9.

Khaksari M, Ahmadi AJ, Sepehri GR. Analysis of the prescription of physicians in Rafsanjan, 1993–1998. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci. 2002;1:3.

Mousavi S, Zargarzadeh A. Rational drug use in Iran: a call for action. J Pharmaceut Care. 2014;2014:47–8.

Aghayar Makouei A, Gharehaghaji R, Saberi A. General practitioners pattern of antibiotic prescription in ambulatory patients in Urmia (1998). J Urmia Univ Med Sci. 2002;13(4):9–15.

Dinarvand R, Nikzad A. Status of prescription and drug usage in Tehran in 1998. Hakim Res J. 2000;3(3):223–31.

Soleymani F, Abdollahi M. Management information system in promoting rational drug use. Int J Pharmacol. 2012;8(Suppl 6):586–9.

Moghadamnia AA, Mirbolooki MR, Aghili MB. General practitioner prescribing patterns in Babol city, Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2002;8(4–5):550–5.

Arab M, Torabipour A, Rahimifrooshani A, Rashidian A, Fadai N, Askari R. Factors affecting family physicians’ drug prescribing: a cross-sectional study in Khuzestan. Iran Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(7):377.

Karimi GHA, Ahmadi P, Del-Pishe A, Korosh K. Factors influencing patterns of antibiotic prescribing in primary health care centers in the savodjbolaq district during 2012–13: a cross-sectional study. J Alborz Univ Med Sci. 2015;3(4):157–67.

Sepehri GR, HajAkbari N, Mousavi A. Prescribing patterns of general practitioners in Kerman province of Iran (2003). J Babol Univ Med Sci. 2005;7(4):76–82.

Alikhani A, Shahamat M, Ghaffarian Shirazi HR. Survey on antibiotic prescription for under 14 years old outpatient children in general practitioner prescriptions in Yasuj Armaghane danesh. 2006;10(4):83–91.

Sepehri G, Meimandi MS. Pattern of drug prescription and utilization among Bam residents during the first six months after the 2003 Bam Earthquake. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2006;21(6):396–402.

Bastani P, Barfar E, Rezapour A, Hakimzadeh SM, Tahernejad A, Panahi S. Rational Prescription of Drug in Iran: Statistics and Trends for Policymakers. J Health Manag Inf. 2018;5(2):35–40.

Antibiotic Use in Outpatient Settings 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/stewardship-report/outpatient.html.

Ghadimi H, Esmaily HM, Wahlstrom R. General practitioners’ prescribing patterns for the elderly in a province of Iran. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(5):482–7.

Sasan MS, Vakili V, Nejat SS, Khajedaluee M. The pattern of antibiotic administration for toddlers and infants with Acute Respiratory Infections (Mashhad, Iran). Iran J Neonatol. 2014;5(3):25–9.

Masoud A, Noori Hekmat S, Dehnavieh R, Haj-Akbari N, Poursheikhali A, Abdi Z. An investigation of prescription indicators and trends among general practitioners and specialists from 2005 to 2015 in Kerman. Iran Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(9):818–27.

Dolat Abadi M, Jalili RH. Patterns of physicians’ drug preh1ion in Sabzevar Iran (2008). J Sabzevar Univ Med Sci. 2009;16(3):161–6.

Ahmadi B, Arab M, Narimisa P, Janani L, Najafpour J. Surveying prescription pattern medication family physician and capitation drug in Ahwaz; 2013.

Sepehri G, Haj-Akbari N, Sepehri E, Mohsen-Beigi M. The quality of prescription drug utilization five years after the 2003 Bam earthquake. Int J Health Care Quality Assur. 2012;25(7):582–91.

Zareshahi R, Haghdoost A, Asadipour A, Sadeghirad B. Rational usage of drug indices in the prescriptions of kerman medical practitioners in 2008. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci. 2012;11(6):523–36.

Mosleh A, Khoshnevis Ansari S, Sorush M, Eghbalpor A, Babaeian S. Evaluation of the drug prescription status based on the WHO indices in pharmacies of health care centers affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Med J Islamic Republic Iran (MJIRI). 2011;25(4):222–5.

Sadeghian GH, Safaeian L, Mahdanian AR, Salami S, Kebriaee-Zadeh J. Prescribing quality in medical specialists in Isfahan, Iran. Iran J Pharm Res. 2013;12(1):235–41.

Safaeian L, Mahdanian AR, Salami S, Pakmehr F, Mansourian M. Seasonality and physician-related factors associated with antibiotic prescribing: a cross-sectional study in Isfahan, Iran. Int J Prevent Med. 2015;6:1.

Sadigh-Rad L, Majdi L, Javaezi M, Delirrad M. Comparison of prescribing indicators of academic versus non-academic specialist physicians in Urmia, Iran. J Res Pharm Pract. 2015;4(2):45–50.

Amani F, Shaker A, Mohammadzadeh SMS. Prescribing pattern and drug indicators in patients visited by general practitioners and specialists in Ardabil city of Iran. Iran J Pharmacol Ther. 2013;12(1):15–8.

Hosseinzadeh F, Sadeghieh Ahari Saeid, Mohammadian-erdi Ali. Survey the antibiotics prescription by general practitioners for outpatients in Ardabil city in 2013. J Ardabil Univ Med Sci. 2016;16(2):140–50.

Eftekhari Gol R, Mousa Farkhani E, Yousefi B. Assessment of drug prescriptions based on WHO indicators in family Physician Program in Razavi Khorasan Province, Iran. J Mashhad Med Council. 2015;19(1):6–10.

Ahmadi F, Zarei E. Prescribing patterns of rural family physicians: a study in Kermanshah Province, Iran. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1.

Rezazadeh A, Abrishami R. Evaluation of prescribing indicators if general practitioners in a military hospital in Tehran. Police Med. 2017;6(1):13–9.

Soleymani F, Godman B, Yarimanesh P, Kebriaeezadeh A. Prescribing patterns of physicians working in both the direct and indirect treatment sectors in Iran: findings and implications. J Pharmaceut Health Serv Res. 2019;10(4):407–13.

Gonzales R, Anderer T, McCulloch CE, Maselli JH, Bloom FJ, Graf TR, et al. A cluster randomized trial of decision support strategies for reducing antibiotic use in acute bronchitis. JAMA Internal Med. 2013;173(4):267–73.

Gulliford MC, van Staa T, Dregan A, McDermott L, McCann G, Ashworth M, et al. Electronic health records for intervention research: a cluster randomized trial to reduce antibiotic prescribing in primary care (eCRT study). Ann Family Med. 2014;12(4):344–51.

Gulliford MC, Prevost AT, Charlton J, Juszczyk D, Soames J, McDermott L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of electronically delivered prescribing feedback and decision support on antibiotic use for respiratory illness in primary care: REDUCE cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2019;364:l236.

Shen X, Lu M, Feng R, Cheng J, Chai J, Xie M, et al. Web-based just-in-time information and feedback on antibiotic use for village doctors in Rural Anhui, China: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(2):e53.

Klein EY, Van Boeckel TP, Martinez EM, Pant S, Gandra S, Levin SA, et al. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(15):E3463–70.

Ahmadi F, Zarei E. Prescribing patterns of rural family physicians: a study in Kermanshah Province, Iran. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):908.

Oduyebo O, Olayinka A, Iregbu K, Versporten A, Goossens H, Nwajiobi-Princewill P, et al. A point prevalence survey of antimicrobial prescribing in four Nigerian Tertiary Hospitals. Ann Trop Pathol. 2017;8(1):42.

Durkin MJ, Jafarzadeh SR, Hsueh K, Sallah YH, Munshi KD, Henderson RR, et al. Outpatient antibiotic prescription trends in the United States: A National Cohort Study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(5):584–9.

Chem ED, Anong DN, Akoachere JFKT. Prescribing patterns and associated factors of antibiotic prescription in primary health care facilities of Kumbo East and Kumbo West Health Districts, North West Cameroon. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0193353e.

Sharland M, Gandra S, Huttner B, Moja L, Pulcini C, Zeng M, et al. Encouraging AWaRe-ness and discouraging inappropriate antibiotic use—the new 2019 Essential Medicines List becomes a global antibiotic stewardship tool. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(12):1278–80.

World Health Organization. Wide differences in antibiotic use between countries, according to new data from WHO 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/rational_use/oms-amr-amc-report-2016-2018-media-note/en/.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

There is no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EN and RA conceived the study idea and design. EN, SE, and RA participated in the literature search, inclusion process, and data abstraction. EN, SE, ZhT, and RA participated in the methodological quality assessment of the included studies and interpretation of data. EN and RA drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the article submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by ethics committee of Kashan University of Medical Sciences (IR.KAUMS.NUHEPMREC.1399.021).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Attachment 1.

Percentage of antibiotic prescribing in all wards of hospitals in Iran. Attachment 2. Percentage of antibiotic prescribing in pediatrics wards of hospitals in Iran. Attachment 3. Percentage of antibiotic prescribing in ICU wards of hospitals in Iran.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nabovati, E., TaherZadeh, Z., Eslami, S. et al. Antibiotic prescribing in inpatient and outpatient settings in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 10, 15 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-021-00887-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-021-00887-x