Abstract

Background

We aimed to compare the clinical characteristics of patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP), and hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae and analyze the antimicrobial resistance and proportion of hypervirluent strains of the microbial isolates.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study on patients with pneumonia caused by K. pneumoniae at the Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan between January 2014 and December 2016. To analyze the clinical characteristics of these patients, data was extracted from their medical records. K. pneumoniae strains were subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility testing, capsular genotyping and detection of the rmpA and rmpA2 genes to identify hypervirulent strains.

Results

We identified 276 patients with pneumonia caused by K. pneumoniae, of which 68 (24.6%), 74 (26.8%), and 134 (48.6%) presented with CAP, HCAP, and HAP, respectively. The 28-day mortality was highest in the HAP group (39.6%), followed by the HCAP (29.7%) and CAP (27.9%) groups. The HAP group also featured the highest proportion of multi-drug resistant strains (49.3%), followed by the HCAP (36.5%) and CAP groups (10.3%), while the CAP group had the highest proportion of hypervirulent strains (79.4%), followed by the HCAP (55.4%) and HAP groups (41.0%).

Conclusion

Pneumonia caused by K. pneumoniae was associated with a high mortality. Importantly, multi-drug resistant strains were also detected in patients with CAP. Hypervirulent strains were prevalent in all 3 groups of pneumonia patients, even in those with HAP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The guidelines of the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) published in 2005 and 2007 classified pneumonia as community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP), hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), or ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) depending on the route of infection [1, 2]. Recently, the ATS/IDSA removed HCAP from the HAP/VAP group in their 2016 guideline update due to the relatively low proportion of multi-drug resistant (MDR) pathogens in this category [3].

K. pneumoniae is a major cause of CAP in Asia and is associated with a high mortality in this region, but it rarely causes CAP in Western countries [4,5,6]. We previously demonstrated that community-onset pneumonia (CAP and HCAP) caused by K. pneumoniae was associated with high 28-day mortality (29.7% of patients) and that the nasopharynx may be a reservoir of K. pneumoniae [4]. A retrospective cohort study in the United States of America identified K. pneumoniae as the second most common gram-negative pathogen responsible for HCAP [7]. K. pneumoniae is an important cause of nosocomial pneumonia, which accounts for around 10% HAP and VAP cases [8] and is associated with the rising rate of MDR strains [9].

In the past 3 decades, hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKp) strains that cause liver abscess with metastatic septic lesions and other pyogenic abscess have emerged in East Asia [10]. The polysaccharide capsule of K. pneumoniae is the most important virulence factor of the pathogen; certain capsular types, such as K1, K2, K5, K20, K54, and K57, are associated with community-onset pyogenic infections [4, 10, 11]. Furthermore, the regulator of the mucoid phenotype genes (rmpA and rmpA2) regulate extracapsular polysaccharide synthesis, thereby controlling the K. pneumoniae mucoid phenotype [12]. There is no consensus on the definition of hvKp strains, but the presence of the virulent capsular types and the expression of the rmpA/rmpA2 genes are typical features [13]. The diagnostic accuracy of such biomarkers that differentiate hypervirulent from classical K. pneumoniae strains has recently been validated [14].

We previously observed that strains with these capsular types are more common in patients with CAP than in those with HCAP [4]. Nonetheless, published studies on the distribution of hypervirulent strains in patients with CAP, HCAP, and HAP caused by K. pneumoniae are lacking. We therefore aimed to compare the clinical characteristics of such patients in a geographical region where hvKp is prevalent and assess the proportion of antimicrobial-resistant and hypervirulent strains among the microbial isolates.

Methods

Study design and patients

A retrospective study was conducted at Taipei Veterans General Hospital, a tertiary-care teaching hospital in Taiwan, from January 2014 to December 2016. All adult patients (aged > 20 years) consecutively admitted with pneumonia caused by K. pneumoniae were included. Patients with polymicrobial infections were excluded, as were patients with incomplete medical records and those diagnosed with liver abscesses with septic lung metastasis, because such abscesses caused by K. pneumoniae are prevalent in Taiwan. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital.

Pneumonia was defined based on the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria by the presence of lung infiltrate with clinical evidence that the infiltrate was of infectious origin, indicated by onset of fever, purulent sputum, leukocytosis, and decline in oxygenation [15]. The definitions of CAP, HCAP, and HAP followed previously described criteria [1,2,3]. Briefly, CAP caused by K. pneumoniae was defined as K. pneumoniae-positive isolates identified upon, or within 48 h of admission in patients who did not fit the criteria for HCAP. HCAP caused by K. pneumoniae was diagnosed in patients with K. pneumoniae-positive isolates identified upon, or within 48 h of admission, who also met any following criteria [1]: 1) having received intravenous therapy at home or in an outpatient clinic within the last 30 days; 2) having received renal dialysis in a hospital or clinic within the last 30 days; 3) having been hospitalized for 2 or more days within the last 90 days; or 4) having resided in a nursing home or long-term care facility. K. pneumoniae-caused pneumonia was considered HAP when K. pneumoniae-positive isolates were identified in patients more than 48 h after admission. Patients with K. pneumoniae-positive isolates discovered more than 48 h after endotracheal intubation were classified as VAP patients as part of the HAP category.

Patient data collection

The following clinical data was extracted from the patients’ medical records: demographic characteristics, co-morbidities, immunosuppression, surgeries, invasive procedures or devices, surgical drainage, mechanical ventilation, severity of illness, outcome, and mortality. We defined appropriate empirical antimicrobial therapy as the administration of at least one antimicrobial agent to which the causative pathogen is susceptible within 24 h of the index date of microbiological study at the approved route and dosage. We defined appropriate definite antimicrobial therapy as the administration of at least one antimicrobial agent to which the causative pathogen is susceptible after obtaining the result of the antimicrobial susceptibility test within 24 h at the approved route and dosage. Prior antibiotic exposure was defined as at least 2 days of therapy within 30 days prior to onset of pneumonia. The Acute Physiology and Chronic and Prevention Evaluation (APACHE) II score was used to determine the severity of the illness within 24 h of the onset of pneumonia [16].

Microbiological analyses

The matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS, bioMérieux SA, Marcy l’Etoile, France) was used for bacterial identification. The VITEK2 system (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) was used for antimicrobial susceptibility test and the results were interpreted according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [17]. MDR K. pneumoniae strains were defined as those not susceptible to at least one agent in 3 or more antimicrobial categories [18].

To identify the capsular genotypes of K .pneumoniae isolates, we performed cps genotyping using the polymerase chain reaction of K-serotype-specific alleles at the wzy loci, including serotypes K1, K2, K5, K20, K54, and K57 [11]. The detection of rmpA and rmpA2 genes was performed as described previously [12]. Hypervirulent strains were defined as those had rmpA or rmpA2 genes [14].

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables using the Student’s t-test and Mann-Whitney U test (Wilcoxon rank-sum test). A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software, version 17.0 (SPSS; IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Clinical characteristics of pneumonia patients caused by K. pneumoniae

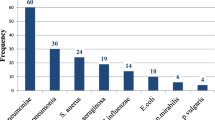

During the study period, a total of 276 consecutive patients with monomicrobial K. pneumoniae-caused pneumonia was identified. Of these, 68 (24.6%), 74 (26.8%), and 134 (48.6%) cases presented with CAP, HCAP, and HAP, respectively. VAP accounted for 29.1% of HAP patients. The mean age of all patients was 75.71 ± 14.82 years and the patients were predominantly male (n = 217, 78.6%). The 28-day mortality rate was 34.1% (94 patients). The overall in-hospital mortality was 46.7% (129 patients).

The clinical patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Chronic kidney disease was a co-morbidity that was more common in the CAP group than in the HAP group (66.2% versus 45.9%, p = 0.015), whereas the frequency of immunosuppression was higher in the HCAP and HAP groups than in the CAP group (25.7% versus 2.9%, p < 0.001; 33.6% versus 2.9%, p < 0.001, respectively). Similarly, the use of invasive procedures and medical devices was higher in the HCAP and HAP groups than in the CAP group (78.4% versus 54.4%, p = 0.002; 88.1% versus 54.4%, p < 0.001, respectively).

Clinical outcomes of pneumonia patients caused by K. pneumoniae

The proportion of appropriately empirical antimicrobials in patients was similar between the HCAP and CAP groups and was higher in both groups compared to the HAP group (85.1% versus 72.4%, p = 0.037; 94.1% versus 72.4%, p < 0.001, respectively) (Table 2). Septic shock at onset of pneumonia was more common in the HCAP group than in the HAP group (44.6% versus 24.6%, p = 0.003). The 28-day mortality was highest in the HAP group (39.6%), followed by the HCAP (29.7%) and CAP (27.9%) groups. The overall in-hospital mortality was similar between the CAP and HCAP groups (33.8% versus 41.9%, p = 0.322), but was lower in the CAP group than in the HAP group (33.8% versus 48.5%, p = 0.047) (Table 2).

Microbiological characteristics of clinical K. pneumoniae strains

The susceptibility of the isolated K. pneumoniae strains to different antimicrobials is shown in Table 3. The proportion of strains with wild-type antibiotic susceptibility (only resistant to ampicillin) was similar between the HCAP and HAP groups (54.1% versus 43.3%, p = 0.149), but was lower in both groups compared to the CAP group (54.1% versus 88.2%, p < 0.001; 43.3% versus 88.2%, p < 0.001, respectively). The proportion of third-generation-cephalosporin-resistant (ceftriaxone or ceftazidime) strains was significantly higher in the HCAP group than in the CAP group (25.7% versus 7.4%, p = 0.004), but lower than in the HAP group (25.7% versus 42.5%, p = 0.016). MDR strains were more prominent in the HCAP group than in the CAP group (36.5% versus 10.3%, p < 0.001), but less frequent than in the HAP group (not statistical significant, 36.5% versus 49.3%, p = 0.076) (Table 3).

The distribution of the hvKp strains (defined by the presence of rmpA/rmpA2 genes) or capsular types among all K. pneumoniae isolates is shown in Table 4. Of all 276 isolated strains, more than half (n = 150, 54.3%) were hvKp strains and 131 (47.5%) belonged to one of the six virulent capsular types (K1, K2, K5, K20, K54, and K57). The proportion of hvKp strains was highest in the CAP group (79.4%), followed by the HCAP (55.4%) and HAP (41.0%) groups. Seventeen (43.6%) of the 39 VAP isolates were hvKp strains. Similarly, the proportion of the six virulent capsular types was highest in the CAP group (67.6%), followed by the HCAP (47.3%) and HAP (37.3%) groups. Notably, MDR-hvKp strains (n = 14, 5.1%) were similarly distributed between the 3 pneumonia categories [n = 2 (2.9%) in the CAP group, n = 4 (5.4%) in the HCAP group, and n = 8 (6.0%) in the HAP group].

Discussion

The current study analyzed the clinical characteristics of patients with K. pneumoniae-caused pneumonia in the 3 different pneumonia categories (CAP, HCAP, and HAP), and evaluated the proportion of antimicrobial-resistant and hypervirulent strains. We observed that the mortality was highest in the HAP group, followed by the HCAP and CAP groups. hvKp strains were prevalent in the 3 categories of pneumonia, with the highest proportion in the CAP group. The HAP group had the highest proportion of MDR strains. The proportion of MDR strains in the HCAP group was significantly higher than that in the CAP group, but the proportion of hvKp strains in the HCAP group was significantly lower than that in the CAP group.

Our previous study, conducted from 2012 to 2014, revealed a high 28-day mortality (29.7%) in patients with community-onset pneumonia caused by K. pneumoniae that did not differ between the pneumonia types HCAP and CAP (34.1% versus 25.5%, p = 0.372) [4]. In the current study, we confirmed a similar 28-day mortality rate in these groups (29.7% versus 27.9%, p = 0.814), but we further discovered an even higher mortality of 39.6% in the HAP group. The overall 30-day reported in the literature for hospitalized patients with CAP caused by all pathogens ranges from 4.0 to 18.0% [19, 20]. The mortality rate for patients with HAP due to all pathogens was found to be 13.1% in the United States [21]. We herein once again emphasized the markedly high mortality of K. pneumoniae-caused pneumonia in Taiwan, which may be attributed to the fact that hvKp strains are prevalent in this country.

In 2016, the ATS/IDSA guidelines recommended that HCAP should be regarded as a form of CAP, as HCAP patients do not tend to be at a high risk to contract MDR pathogens [3]. In the present study, we focused on pneumonia caused by K. pneumoniae and discovered that the proportion of MDR strains in HCAP patients was lower than that in HAP patients (36.5% versus 49.3%, p = 0.076), but significantly higher than that in CAP patients (36.5% versus 10.3%, p < 0.001). One recent review suggested that the prevalence of CAP caused by MDR K. pneumoniae might be related to the consumption of antibiotics by these patients, particularly in Asian countries [22]. In the era of increasing antimicrobial resistance, the validation of predictive scores for different MDR pathogens is warranted to avoid excessive use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials.

hvKp strains are very common in East Asia and usually cause community-acquired pyogenic infections, even in healthy hosts. Classical K. pneumoniae strains are typically associated with multi-drug resistance and primarily affect hospitalized patients with comorbidities [23]. In contrast, hvKp strains are usually susceptible to most antimicrobials except for ampicillin. In the present study, we identified the highest proportion of hvKp strains in the CAP group (79.4%), followed by the HCAP (55.4%) and HAP (41.0%) groups. Furthermore, hvKp strains were common in patients with VAP (17/39, 43.6%). Published studies on the proportion of hvKp strains in hospital-acquired infections are scarce. Yan et al. reported that hvKp strains accounted for 28.6% of all K. pneumoniae strains that caused VAP in a university hospital in Hunan, China [24]. Another study conducted in China by Liu et al. identified 46.6% of all K. pneumoniae strains causing VAP in elderly patients in two tertiary hospitals as hvKp strains [25].

We herein demonstrated for the first time the notably high proportion of hvKp strains causing HAP/VAP outside of China. This observation suggests that hvKp strains have spread from the communities to hospitals in East Asia. We have previously shown that nasal carriage of hvKp strains is common in outpatient patients [4], and HAP/VAP might be an endogenous infection in hospitalized patients. The hvKp strains attacking these vulnerable patients pose a major concern in terms of hospital-acquired infections. Moreover, Liu et al. found that hvKp strains with antimicrobial resistance causing VAP are increasing [25], consistent with the fact that MDR-hvKp strains have emerged in China and are usually fatal due to the limited choice of antimicrobials and their virulence [26, 27]. We have recently reported the high mortality associated with MDR-hvKp infections in Taiwan [28, 29], and we identified 14 MDR-hvKp strains in the current study.

The major limitation of this study is its retrospective design. In addition, our study was conducted in a single tertiary care teaching hospital and the results may therefore not be generalizable due to different patient populations in other hospitals and countries. Furthermore, we did not perform multi-locus sequence typing of K. pneumoniae isolates to describe their clonal distribution among the 3 pneumonia groups. Nonetheless, our study describes fort the first time the clinical characteristics of patients with K. pneumoniae-caused pneumonia in the 3 pneumonia categories and the microbiological features of these strains.

Conclusions

Pneumonia caused by K. pneumoniae was associated with a high mortality in general and in the HAP group in particular. Notably, we discovered the prevalence of hvKp strains in all 3 pneumonia groups, even in the HAP group (41% of strains in this group). The fact that vulnerable patients were infected with hvKp strains poses a treatment challenge of patients both from the community and in the hospitals in regions where such strains are prevalent. Surveillance should focus on the prevalence of hvKp strains in addition to MDR strains to allow for appropriate management of this disease in the future.

Availability of data and materials

All materials and data analyzed during this study are contained within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CAP:

-

Community-acquired pneumonia

- HAP:

-

Hospital-acquired pneumonia

- HCAP:

-

Healthcare-associated pneumonia

- hvKp:

-

Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae

- MDR:

-

Multi-drug resistant

- VAP:

-

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

References

American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:388–416.

Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–72.

Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, Muscedere J, Sweeney DA, Palmer LB, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e61–e111.

Lin YT, Wang YP, Wang FD, Fung CP. Community-onset Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumonia in Taiwan: clinical features of the disease and associated microbiological characteristics of isolates from pneumonia and nasopharynx. Front Microbiol. 2015;9:122.

Song JH, Oh WS, Kang CI, Chung DR, Peck KR, Ko KS, et al. Epidemiology and clinical outcomes of community-acquired pneumonia in adult patients in Asian countries: a prospective study by the Asian network for surveillance of resistant pathogens. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31:107–14.

Lin YT, Jeng YY, Chen TL, Fung CP. Bacteremic community-acquired pneumonia due to Klebsiella pneumoniae: clinical and microbiological characteristics in Taiwan, 2001-2008. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:307.

Kollef MH, Shorr A, Tabak YP, Gupta V, Liu LZ, Johannes RS. Epidemiology and outcomes of health-care-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2005;128:3854–62.

Jones RN. Microbial etiologies of hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(Suppl 1):S81–7.

Navon-Venezia S, Kondratyeva K, Carattoli A. Klebsiella pneumoniae: a major worldwide source and shuttle for antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2017;41:252–75.

Siu LK, Yeh KM, Lin JC, Fung CP, Chang FY. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:881–7.

Fang CT, Lai SY, Yi WC, Hsueh PR, Liu KL, Chang SC. Klebsiella pneumoniae genotype K1: an emerging pathogen that causes septic ocular or central nervous system complications from pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:284–93.

Hsu CR, Lin TL, Chen YC, Chou HC, Wang JT. The role of Klebsiella pneumoniae rmpA in capsular polysaccharide synthesis and virulence revisited. Microbiology. 2011;157:3446–57.

Harada S, Doi Y. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: a Call for Consensus Definition and International Collaboration. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:e00959-18.

Russo TA, Olson R, Fang CT, Stoesser N, Miller M, MacDonald U, et al. Identification of Biomarkers for Differentiation of Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae from Classical K. pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56:e00776-18.

Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309–32.

Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–29.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 27th informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S27. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017.

Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–81.

Lauderdale TL, Chang FY, Ben RJ, Yin HC, Ni YH, Tsai JW, et al. Etiology of community acquired pneumonia among adult patients requiring hospitalization in Taiwan. Respir Med. 2005;99:1079–86.

Prina E, Ranzani OT, Torres A. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet. 2015;386:1097–108.

Giuliano KK, Baker D, Quinn B. The epidemiology of nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46:322–7.

Cillóniz C, Dominedó C, Torres A. Multidrug Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria in Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Crit Care. 2019;23:79.

Sellick JA, Russo TA. Getting hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae on the radar screen. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018;31:341–6.

Yan Q, Zhou M, Zou M, Liu WE. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae induced ventilator-associated pneumonia in mechanically ventilated patients in China. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35:387–96.

Liu C, Guo J. Characteristics of ventilator-associated pneumonia due to hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae genotype in genetic background for the elderly in two tertiary hospitals in China. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:95.

Zhang R, Lin D, Chan EW, Gu D, Chen GX, Chen S. Emergence of Carbapenem-resistant serotype K1 Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:709–11.

Gu D, Dong N, Zheng Z, Lin D, Huang M, Wang L, et al. A fatal outbreak of ST11 carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Chinese hospital: a molecular epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:37–46.

Huang YH, Chou SH, Liang SW, Ni CE, Lin YT, Huang YW, et al. Emergence of an XDR and carbapenemase-producing hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae strain in Taiwan. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:2039–46.

Lin YT, Cheng YH, Juan CH, Wu PF, Huang YW, Chou SH, et al. High mortality among patients infected with hypervirulent antimicrobial-resistant capsular type K1 Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in Taiwan. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;52:251–7.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Medical Science and Technology Building of Taipei Veterans General Hospital for providing experimental space and facilities. This study was presented in part at the ASM Microbe 2018 in Atlanta, The United States of America, 7-11 June, 2018 (Abstract number: 4541).

Funding

This study was partly supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan (MOST 105–2628-B-010-015-MY3 and MOST 108-2314-B-010-030-MY3), the Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V107A-006 and V108C-026), Taipei Veterans General Hospital-National Yang-Ming University Excellent Physician Scientists Cultivation Program (107-V-B-017), and the Szu-Yuan Research Foundation of Internal Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C-HJ, and Y-TL participated in the study design, analysis of data, and writing of the manuscript. Y-TL participated in the laboratory experiment. C-HJ, S-YF, C-HC, T-YT, and Y-TL participated in the data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital (protocol number 2017–07-007 AC). No written informed consent was acquired due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Juan, CH., Fang, SY., Chou, CH. et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with pneumonia caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan and prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant and hypervirulent strains: a retrospective study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 9, 4 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-019-0660-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-019-0660-x