Abstract

We present an example of a difference equation of arbitrary order, possessing the right-hand side function that is homogeneous to a certain degree and nonincreasing in each variable, which has a unique positive equilibrium, as well as solutions that do not converge to the equilibrium. The example shows that the main result in the paper: O. Moaaz, Dynamics of difference equation \(x_{n+1}=f(x_{n-l}, x_{n-k})\) (Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018:447, 2018), is incorrect.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Let, as usual, \({\mathbb{N}}\) be the set of positive integers, \({\mathbb{Z}}\) the set of integers, \({\mathbb{R}}\) the set of reals, and \({\mathbb{C}}\) the set of the complex numbers. By \({\mathbb{N}}_{k}\), where \(k\in {\mathbb{Z}}\), we denote the set of all \(j\in {\mathbb{Z}}\) such that \(j\ge k\). If \(p,q\in {\mathbb{Z}}\) and such that \(p\le q\), then the notation \(j=\overline{p,q}\) means that j takes the values of all integers between p and q (including p and q).

Difference equations and systems of difference equations have been studied analytically for more than three hundred years. The first important results were obtained by de Moivre [3, 4] and D. Bernoulli [2]. For some classical results, see, for example, [5, 7–13, 15]. All these references are to some extent devoted to finding closed-form formulas for solutions to linear or nonlinear difference equations and systems of difference equations. There has been some renewed interest in the solvability of difference equations and systems of difference equations, their invariants, and applications of obtained closed-form formulas for their solutions and/or invariants (see, for example, [1, 16–28] and related references therein). It is a common fact that many solvable difference equations and systems are transformed by some suitable changes of variables to some solvable linear ones [1, 19, 22, 23, 25–28].

Of the many classes of difference equations and systems of difference equations solvable in closed form, here we mention an important class, which is used in this note. In addition, we also mention a simple method for getting a sequence of difference equations or systems of difference equations from a given one, which can sometimes be used to obtain some counterexamples in the theory of difference equations.

1.1 Product-type difference equations

Some recent investigations on solvability are devoted to product-type difference equations and systems of difference equations, or to some difference equations and systems that can be reduced to them using some suitable transformations (see, e.g., [22–24] and the related references therein).

General product-type difference equation is

where the sequences \((a_{n})_{n\in {\mathbb{N}}_{0}}\), \((\alpha _{n}^{(j)})_{n\in {\mathbb{N}}_{0}}\), \(j=\overline{0,k-1}\), as well as the initial values \(x_{j}\), \(j=\overline{0,k-1}\), are real or complex.

In some cases, equation (1) can be solved by taking the logarithm, but in the case of complex initial values \(x_{j}\), \(j=\overline{0,k-1}\), coefficients and exponents, some other methods can be used (see, e.g., [22–24] and the related reference therein). Since the equation is related to the general linear difference equation, it is of great importance.

1.2 Difference equations with interlacing indices

There is a simple method enabling to construct a family of ‘cloned’ difference equations from a given one. The equations are called the difference equations with interlacing indices [27]. The equations appear from time to time in the literature, and it seems that some authors are not aware that they are obtained by cloning some simpler difference equations (see the examples and analyses conducted in [25–28]). However, the equations can be useful in providing some counterexamples in the theory of difference equations (see, e.g., [6]). Systems of difference equations with interlacing indices can also be constructed by the cloning method. Now we briefly describe the method.

The general form of the difference equation with interlacing indices is the following

where \(l\in {\mathbb{N}}\), and \(k\ge 2\).

If we define k sets of indices by

we obviously have

and

Let

then from (2), we have

for \(j=\overline{0,k-1}\).

This means that the sequences \((y_{s}^{(j)})_{s\in {\mathbb{N}}_{0}}\), \(j=\overline{0,k-1}\) are k solutions to the equation

with unrelated initial values.

Using this procedure in the reverse direction, from equation (3), one can obtain a family of cloned equations in (2), i.e., a family of difference equations with interlacing indices.

1.3 Global convergence results and a claim

One of the main problems in the theory of difference equations is the convergence of the solutions to the equations. There are many results on convergence in the literature, some of which can be found in the literature mentioned above.

The following difference equation

where \(k,m\in {\mathbb{N}}_{0}\), has been recently studied in [14].

The following claim is the main result concerning the difference equations appearing in [14] (Theorem 3.3 therein).

Theorem A

Assume that f has non-positive partial derivatives and is homogeneous with degree s. Then equation (4) has a unique positive equilibrium \(x^{*}\), and every solution to the equation converges to \(x^{*}\).

In this note, we show that the claim in Theorem A is not true by giving an example of equation (4) such that the function f is homogeneous (with a degree to be chosen appropriately) and has non-positive partial derivatives, and equation (4) has a unique positive equilibrium \(x^{*}\) and solutions that do not converge to the equilibrium.

2 A counterexample to Theorem A

In this section, we give a counterexample to Theorem A. To construct the counterexample, we are looking for a difference equation belonging to the above classes of equations; that is, we are looking for a product-type difference equation with interlacing indices that is solvable in the closed form.

Example 1

Consider the difference equation

where \(k\in {\mathbb{N}}\), and \(\alpha >1\), which is a special case of the general difference equation of higher order

where \(k\in {\mathbb{N}}\), and f is an arbitrary function.

Here we are interested in positive solutions to equation (5). Hence, we assume that

For the case of equation (5), we have that

is the right-hand side function, which generates their solutions along with the initial values.

Since

and

when \(t_{k}>0\), we have that the function (7) has non-positive partial derivatives on the set \((0,+\infty )^{k}\), from which we choose our initial values.

On the other hand, since

holds for every \(\lambda >0\), we see that the function defined in (7) is homogeneous with degree −α.

Further, if

is an equilibrium solution to equation (5), then it must be

from which it immediately follows that \(x^{*}=1\), which means that equation (5) has a unique positive equilibrium.

Now note that equation (5) is a difference equation with interlacing indices, which is obtained by cloning the following product-type difference equation of first order

that is, equation (5) consists of k copies of equation (8) with initial values not connected to each other.

Equation (8) obviously has the same equilibrium. Hence, to show that the claim of Theorem A is not true, it is enough to show that equation (8) has solutions, which do not converge to the equilibrium.

Now note that by iterating equation (8), we get

and

for \(n\in {\mathbb{N}}_{0}\).

By a simple inductive argument from relations (9), (10), and equation (8) with \(n=1\), one can easily obtain

and

for \(n\in {\mathbb{N}}_{0}\).

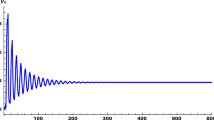

Taking \(\alpha >1\), we have

Hence, if \(y_{0}\in (0,1)\), then letting \(n\to +\infty \) in (11) and (12) and using (13), it follows that

and

Besides this, if \(y_{0}>1\), then letting \(n\to +\infty \) in (11) and (12) and using (13), we obtain

and

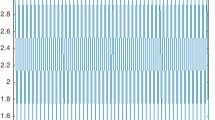

From the relations (14)–(17), we see that if any initial value of equation (8) belongs to the set \((0,+\infty )\setminus \{1\}\), the solution is unbounded. This fact implies that if any initial value of equation (5) belongs to the set \((0,+\infty )\setminus \{1\}\), the solution is unbounded.

The above analysis shows that the claim of Theorem A is not true.

Remark 1

Note that the only bounded positive solution to equation (5) is the one which is generated by the initial values

The solution is, in fact, the equilibrium solution \(x_{n}\equiv 1\), \(n\in {\mathbb{N}}_{0}\), which is easily proved using the initial values (18) in equation (5), together with a simple inductive argument.

Remark 2

The above consideration also shows that the equilibrium solution is the unique positive solution to equation (5) that converges, which indicates to what extent the claim in Theorem A fails.

Remark 3

Note also that the linearized equation associated with equation (8) about the equilibrium point is

from which, along with the assumption \(\alpha >1\), it follows that the equilibrium is a repeller. Note that from (19), we have \(|z_{n}|=\alpha ^{n}|z_{0}|\), \(n\in {\mathbb{N}}_{0}\), from which together with (13), we see that for each \(z_{0}\ne 0\), the solution to (19) goes to infinity as \(n\to +\infty \).

Given that equation (8) is solvable and has a closed-form formula for its solutions, from which their long-term behavior is easily described, linearization is not required. However, the linearization argument also suggests in which direction counterexamples should be sought.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Berg, L., Stević, S.: On some systems of difference equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 218, 1713–1718 (2011)

Bernoulli, D.: Observationes de seriebus quae formantur ex additione vel substractione quacunque terminorum se mutuo consequentium, ubi praesertim earundem insignis usus pro inveniendis radicum omnium aequationum algebraicarum ostenditur. Comment. Acad. Petropol. III 1728, 85–100 (1732) (in Latin)

de Moivre, A.: Miscellanea Analytica de Seriebus et Quadraturis. Tonson & Watts, Londini (1730) (in Latin)

de Moivre, A.: The Doctrine of Chances, 3rd edn. Strand Pub., London (1756)

Fort, T.: Finite Differences and Difference Equations in the Real Domain. Oxford University Press, London (1948)

Jekl, J.: Special cases of critical linear difference equations. Electron. J. Qual. Theory Differ. Equ. 2021, Article ID 79 (2021)

Jordan, C.: Calculus of Finite Differences. Chelsea, New York (1956)

Lacroix, S.F.: Traité des differénces et des séries. Paris, (1800) (in French)

Lagrange, J.-L.: OEuvres, t. II. Gauthier-Villars, Paris (1868) (in French)

Laplace, P.S.: Recherches sur l’intégration des équations différentielles aux différences finies et sur leur usage dans la théorie des hasards. Mémoires de l’ Académie Royale des Sciences de Paris 1773, t. VII, (1776) (Laplace OEuvres, VIII, 69–197, 1891). (in French)

Markoff, A.A.: Differenzenrechnung. Teubner, Leipzig (1896) (in German)

Milne-Thomson, L.M.: The Calculus of Finite Differences. Macmillan & Co., London (1933)

Mitrinović, D.S., Kečkić, J.D.: Metodi Izračunavanja Konačnih Zbirova/Methods for Calculating Finite Sums. Naučna Knjiga, Beograd (1984) (in Serbian)

Moaaz, O.: Dynamics of difference equation \(x_{n+1}=f(x_{n-l}, x_{n-k})\). Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, Article ID 447 (2018)

Nörlund, N.E.: Vorlesungen über Differenzenrechnung. Springer, Berlin (1924) (in German)

Papaschinopoulos, G., Schinas, C.J.: Invariants for systems of two nonlinear difference equations. Differ. Equ. Dyn. Syst. 7, 181–196 (1999)

Papaschinopoulos, G., Schinas, C.J.: Invariants and oscillation for systems of two nonlinear difference equations. Nonlinear Anal., Theory Methods Appl. 46, 967–978 (2001)

Papaschinopoulos, G., Schinas, C.J., Stefanidou, G.: On a k-order system of Lyness-type difference equations. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2007, Article ID 31272 (2007)

Papaschinopoulos, G., Stefanidou, G.: Asymptotic behavior of the solutions of a class of rational difference equations. Int. J. Difference Equ. 5(2), 233–249 (2010)

Schinas, C.: Invariants for difference equations and systems of difference equations of rational form. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 216, 164–179 (1997)

Schinas, C.: Invariants for some difference equations. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 212, 281–291 (1997)

Stević, S.: Solvable product-type system of difference equations whose associated polynomial is of the fourth order. Electron. J. Qual. Theory Differ. Equ. 2017, Article ID 13 (2017)

Stević, S.: Solvability of a product-type system of difference equations with six parameters. Adv. Nonlinear Anal. 8(1), 29–51 (2019)

Stević, S.: New class of practically solvable systems of difference equations of hyperbolic-cotangent-type. Electron. J. Qual. Theory Differ. Equ. 2020, Article ID 89 (2020)

Stević, S., Ahmed, A.E., Kosmala, W., Šmarda, Z.: Note on a difference equation and some of its relatives. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 44, 10053–10061 (2021)

Stević, S., Ahmed, A.E., Kosmala, W., Šmarda, Z.: On a class of difference equations with interlacing indices. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2021, Article ID 297 (2021)

Stević, S., Diblik, J., Iričanin, B., Šmarda, Z.: On some solvable difference equations and systems of difference equations. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2012, Article ID 541761 (2012)

Stević, S., Iričanin, B., Kosmala, W., Šmarda, Z.: Note on the bilinear difference equation with a delay. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 41, 9349–9360 (2018)

Acknowledgements

The work of Zdeněk Šmarda was supported by the project FEKT-S-20-6225 of Brno University of Technology.

Funding

Brno University of Technology, project FEKT-S-20-6225.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS investigated possibilities for finding a counterexample to Theorem A. BI, WK and ZŠ analyzed some original ideas in order to find as much as possible simpler counterexample to the theorem. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stević, S., Iričanin, B., Kosmala, W. et al. Note on difference equations with the right-hand side function nonincreasing in each variable. J Inequal Appl 2022, 25 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13660-022-02761-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13660-022-02761-9