Abstract

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is common in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19). We aimed to explore the changes in AKI epidemiology between the first and the second COVID wave in the United Kingdom (UK).

Methods

This was an observational study of critically ill adult patients with COVID-19 in an expanded tertiary care intensive care unit (ICU) in London, UK. Baseline characteristics, organ support, COVID-19 treatments, and patient and kidney outcomes up to 90 days after discharge from hospital were compared.

Results

A total of 772 patients were included in the final analysis (68% male, mean age 56 ± 13.6). Compared with wave 1, patients in wave 2 were older, had higher body mass index and clinical frailty score, but lower baseline serum creatinine and C-reactive protein (CRP). The proportion of patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation (MV) on ICU admission was lower in wave 2 (61% vs 80%; p < 0.001). AKI incidence within 14 days of ICU admission was 76% in wave 1 and 51% in wave 2 (p < 0.001); in wave 1, 32% received KRT compared with 13% in wave 2 (p < 0.001). Patients in wave 2 had significantly lower daily cumulative fluid balance (FB) than in wave 1. Fewer patients were dialysis dependent at 90 days in wave 2 (1% vs. 4%; p < 0.001).

Conclusions

In critically ill adult patients admitted to ICU with COVID-19, the risk of AKI and receipt of KRT significantly declined in the second wave. The trend was associated with less MV, lower PEEP and lower cumulative FB.

Trial registration: NCT04445259.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since 2019, the world has faced multiple waves of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections. Different viral strains, new diagnostics, therapies and vaccines have impacted the phenotype and course of the disease. Despite these advances, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) continues to pose significant challenges for patients, healthcare providers and healthcare systems [1,2,3,4,5].

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common complication of COVID-19, affecting 25–77% of patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) and associated with major challenges for the healthcare team [4, 6,7,8,9,10]. Between 5 and 44% of patients receive kidney replacement therapy (KRT) [11,12,13,14,15,16]. We hypothesised that the incidence of COVID-19 associated AKI and KRT rates had declined since the beginning of the pandemic [17,18,19,20,21]. The aims of this study were to compare the epidemiology of COVID-19-associated AKI between the first and second wave of the pandemic and to identify key contributing factors.

Materials and methods

Setting, population, and ethical approval

This was a single-centre prospective analysis of critically ill COVID-19 patients admitted to a university-affiliated tertiary care hospital in London, between March 1st 2020 and February 28th 2021. The centre has 64 critical care beds, but capacity was expanded to 220 beds at the peak of the second wave.

We included adult (≥ 18 years) patients with COVID-19 confirmed by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction on nasopharyngeal or endobronchial samples. We excluded (1) patients with pre-existing end stage kidney disease (ESKD), (2) kidney transplant recipients, and (3) patients in whom COVID-19 was not the primary cause of ICU admission. In case of multiple admissions, only the first was included.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Research Authority and the Research Ethics Committee Health and Care Research Wales (REC Reference 20/WA/0175). Informed consent was obtained from the patients, personal, or professional consultee. The study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04445259), conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and reported using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Data collection

The details of data collection were previously published [11]. In brief, baseline characteristics, comorbidities, laboratory parameters and organ support on admission were collected. COVID-19 treatments (e.g. immunomodulatory therapies, antivirals, proning, anticoagulation, etc.), daily fluid intake and output (day 1–7), daily serum creatinine (SCr) and urine output until day 14 and complications during hospital admission were recorded. Data were obtained through manual chart reviews by trained researchers and subsequently verified. Laboratory parameters were extracted from electronic health records. SCr results after hospital discharge were obtained from local care records or by contacting general practitioners. The last follow-up date was August 31st 2021.

Patients were grouped into wave 1 or 2. Wave 1 included the period March–August 2020, and wave 2 referred to September 2020–February 2021 [21]. The Kidney Diseases: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) classification was used to define and stage AKI using both SCr and urine output criteria [22]. In obese patients, we calculated hourly urine output based on ideal body weight [23]. Baseline SCr was determined from the lowest outpatient SCr values between 7 and 365 days before ICU admission [24]. If a historical SCr result was unavailable, we used the lower values between the first SCr on hospital admission or SCr derived from the back-calculation of an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 75 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula [22]. New-onset AKI was defined as AKI which developed more than 48 h after ICU admission.

Kidney recovery was defined as having SCr < 1.5 times baseline value and being dialysis independent and alive [25]. Patients with AKI were divided into 3 groups according to AKI duration from the day of AKI diagnosis until kidney recovery; transient (≤ 2 days), persistent-medium (3–6 days), and persistent-long duration (≥ 7 days or non-recovery) [26]. Cumulative fluid balance (FB) (%) was calculated as [total fluid intake (L) – total output of all body fluids (L) × 100] divided by body weight on admission (kg) [27]. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 [28].

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the occurrence of AKI within 14 days after ICU admission. Secondary outcomes were the differences between wave 1 and 2 of the following: (1) KRT rate within 14 days after ICU admission; (2) risk factors for overall AKI and KRT; (3) risk factors for new AKI and KRT after 48 h, and (4) patient and kidney outcomes at ICU and hospital discharge, and at 90 days.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics, complications, COVID-19 treatments, kidney outcomes and mortality were stratified by wave. Binary and categorical variables are presented using counts and percentages. The distributions of continuous variables were assessed using coefficients of skewness and summarised as either mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables or median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed variables. To assess for differences between the waves, binary or categorical variables were assessed using the Chi-square test. Mann–Whitney U test or t test were undertaken for continuous data depending on the distribution.

AKI incidence rates within 14 days after ICU admission are presented as cumulative incidence and events/100 person-days, using mortality and ICU discharge before 14 days as competing risks. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for 90-day mortality with AKI modelled as a time-varying covariate.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were used to examine the relationship between demographics (exposures) and AKI or KRT (outcomes). The multivariate models were all adjusted for new systemic steroid therapy, remdesivir, interleukin (IL)-6 antagonists and invasive vs non-invasive ventilation. Further adjustments were made for COVID-19 wave (1 vs. 2), age, gender, and ethnicity where indicated. Regression coefficients are represented as odds ratios (OR) with a 95% CI.

To explore the relationship between cumulative FB at 48 h after ICU admission and the development of new AKI and KRT, we differentiated between 5 FB groups (< − 2%, − 2% to 0%, 0% to + 2% (reference group), + 2% to + 4% and > + 4%). Groups were combined if the number of patients in one category was small. Patients with AKI or KRT within 48 h of admission were excluded from the model investigating new AKI and KRT, respectively.

Sensitivity analysis

To further explore the association between 24-h cumulative FB and AKI and KRT, we performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding patients with AKI or KRT within 24 h of hospital admission.

Results

Baseline characteristics, ICU management and complications

Between March 1st 2020 and February 28th 2021, 847 critically ill SARS-CoV-2 positive patients were admitted to ICU. A total of 772 patients were included in the final analysis: 316 (40.9%) from the first wave and 456 (59.1%) from the second wave (Fig. 1). Compared with wave 1, patients admitted to ICU in wave 2 were older, had a higher body mass index (BMI), lower Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, higher clinical frailty score and were less likely to be of black ethnicity (Table 1). In wave 2, patients had higher neutrophil counts and lower baseline SCr, ferritin, C-reactive protein (CRP), PaO2/FiO2 ratio and lymphocyte counts at ICU admission. They were less likely to receive invasive MV (61% vs. 80%; p < 0.001) and vasopressor support (30% vs. 42%; p < 0.01) on admission compared with patients in wave 1. In patients who received invasive MV, the maximum levels of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) in the first 48 h were significantly lower in wave 2 than wave 1.

During the first 14 days in ICU, patients in wave 2 were more likely to receive steroids (99% vs. 59%; p < 0.001), remdesivir (41% vs. 6%; p < 0.001) and IL-6 antagonists (27% vs. 1%; p < 0.001) than patients in wave 1 (Table 2). In those who received steroids, the median dose of dexamethasone or equivalent was higher in wave 2 than wave 1 (22.5 mg [IQR 13.2–39.6] vs. 18.8 mg [IQR 11.1–30]; p < 0.001). The use of therapeutic anticoagulation and proning were comparable. Overall complications were similar, except for lower incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome and myopericarditis in wave 2.

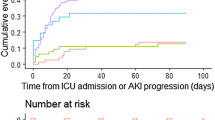

AKI diagnosis, incidence, and characteristics

True baseline SCr results were available for 278 patients (36%). AKI was defined by SCr in 27.7%, urine output in 20.9% and both criteria in 51.4%. On ICU admission, AKI was prevalent in 121 (38%) in wave 1 and 110 (24%) in wave 2 (p < 0.001). The overall AKI incidence within 14 days after ICU admission was 76% in wave 1 and 51% in wave 2 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The cumulative incidence rate of AKI was 28.5 events/100-person days (95% CI 23.8–34.2) in wave 1 and 22.7 events/100-person days (95% CI 18.9–27.1) in wave 2, accounting for mortality and ICU discharge as competing risks. The numbers and proportions of AKI and KRT relative to ICU admission are shown in Additional file 1: Figs. S1, S2. The median day of AKI onset was 1 (IQR 0–5) in wave 1 and 4 (IQR 1–10) in wave 2. Patients admitted in wave 1 were more likely to have more severe and more prolonged AKI (Table 2). Characteristics between patients with and without AKI stratified by wave are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Multivariate analysis demonstrates that age, BMI, admission SOFA score, invasive MV, higher baseline SCr, high CRP, low pH and low ionised calcium on admission were associated with AKI (Table 3; Additional file 1: Table S2).

KRT rate and risk factors

The KRT rate was lower in wave 2 than wave 1 (13% vs. 32%; p < 0.001). The median day of KRT initiation was 3 (IQR 1–6) in wave 1 and 4 (IQR 1–10) in wave 2. The median duration of KRT was 12 (IQR 6–22) days in wave 1 and 11 (IQR 5–23) days in wave 2. The most common indications for KRT in both waves were uremia and oliguria (Additional file 1: Table S3). Multivariate analysis showed that high BMI, invasive MV, high baseline SCr, high lactate, high white blood cell count and high CRP, low pH and low ionised calcium were associated with KRT (Additional file 1: Table S4).

Risk factors for new AKI and KRT

Compared with wave 2, patients in wave 1 had a higher daily FB despite being administered diuretics more frequently (Fig. 3). The difference was more noticeable in patients admitted from the emergency department and ward but not in those transferred from other hospitals (Additional file 1: Table S5). After adjusting for age, gender, ethnicity, wave, non-renal SOFA, vasopressor use, invasive MV, PEEP levels, diuretics, change in fluid balance and COVID-19 therapies, a positive cumulative FB was independently associated with new AKI and KRT [adjusted OR for 48-h FB > 2% and AKI 2.55 (95% CI 1.46, 4.50); adjusted OR for 48-h FB > 4% and KRT 4.16 (95% CI 2.03, 8.51) (Table 4; Fig. 4).

Multivariate analysis showed that treatment with systemic steroids, remdesivir and/or IL-6 antagonists was not associated with AKI development; however, new steroid use was positively associated with KRT after 48 h (adjusted OR 3.18, 95% CI 1.59, 6.36) (Additional file 1: Tables S6, S7).

Patient and kidney outcomes

The ICU, hospital and 90-day mortality and lengths of stay were similar in both waves (Table 2). AKI was independently associated with 90-day mortality (adjusted HR 2.20, 95% CI 1.16–4.14), adjusted for age, sex, ventilation type, APACHE II score, remdesivir, steroids, IL-6 antagonists, and wave. At hospital discharge, kidney recovery was observed in 89% of AKI patients in wave 2 compared with 83% in wave 1 (p < 0.01). Dialysis dependence at discharge was 2% in alive patients in wave 2 compared to 4% in wave 1. At 90 days, 1% of survivors in wave 2 were dialysis dependent compared to 4% in wave 1 (p < 0.001). There were no significant changes in SCr or eGFR from baseline, at hospital discharge, and at 90 days between wave 1 and 2 (Additional file 1: Table S8). The proportion of patients with CKD at 90 days was 14% in wave 1 vs. 11% in wave 2. The risk was higher in patients with more severe AKI (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis for the association between 24-h cumulative FB and risk of new AKI and KRT by excluding patients with AKI or KRT within 24 h of ICU admission. Cumulative FB > 2% was independently associated with KRT receipt after 24 h (adjusted OR 2.14, 95% CI 1.16, 3.94) (Additional file 1: Table S9).

Discussion

This large analysis of critically ill patients describes changes in AKI epidemiology during the COVID-19 pandemic. The key findings are that fewer ICU patients developed AKI and received KRT in wave 2 despite being older and frailer. When AKI occurred, it was milder, shorter, occurred later and had a better longer-term prognosis. A positive cumulative FB and invasive MV were independent risk factors for new AKI and KRT.

Whilst the improvement may be related to better general management of patients with COVID-19, we also noted that patients had lower baseline SCr values and lower inflammatory markers on admission to ICU (i.e. CRP and ferritin). High CRP is a known risk factor for AKI and KRT [18, 29]. The decline in CRP in patients admitted to ICU during the course of the pandemic might be explained by differences in viral strains or changes in clinical management [17]. Further, the reduced application of invasive MV may have reduced the AKI risk. In the early phase of the pandemic, early intubation was suggested to avoid cross-infection of healthcare workers and to reduce the risk of self-inflicted lung injury [30,31,32,33,34,35]. This concept changed over time following cumulative data confirming that non-invasive ventilation (NIV) with or without awake prone positioning was effective and safe [36,37,38].

It has also been suggested that the observed decline in AKI incidence may be due to changes in fluid management, i.e. the abandonment of fluid restriction “to keep the lungs dry” [39]. Our data do not support this hypothesis. In fact, daily cumulative FB was significantly higher in wave 1 than in wave 2 despite using diuretics more often. This is in keeping with results from non-COVID-19 studies showing that higher FB is associated with more AKI and higher need for KRT and longer durations of KRT [27, 40,41,42,43,44].

Another potential explanation for the decline in AKI incidence is the increased use of anti-inflammatory therapies [45]. Landmark studies have reported lower KRT rates in patients who received dexamethasone and tocilizumab [46, 47]. Together with others, we previously reported less AKI progression with steroids [11, 48]. However, a subsequent analysis of a large multi-centre database from the UK did not confirm an association between declining AKI rates and treatment with steroids or remdesivir [19]. In our analysis, steroid use was associated with reduced risk of AKI in univariate analysis but increased risk of KRT in multivariate analysis. These conflicting results suggest that there might be confounding factors that have not been accounted for. For instance, selection bias, interactions between types, doses, and duration of treatments, patient heterogeneity and disease phenotypes [49] may have impacted the risk of AKI and KRT. It should also be acknowledged that the evidence for specific COVID-19 therapies emerged at different times during the pandemic [4]. Although steroids and remdesivir were officially recommended in the UK in May 2020 and IL-6 antagonists were recommended in December 2020, some patients received these medications earlier, for instance, as part of clinical trials [50].

The improved longer-term renal prognosis in the second wave could possibly be explained by a lower proportion of patients with pre-existing CKD. Although the risk of CKD at 90 days declined, it remained relatively high at 11% and as high as 30% in patients with AKI stage 3. At present, little is known about long-term kidney outcomes post-COVID. Hospitalised non-ICU patients with COVID-associated AKI were found to have a greater 6-month decline in eGFR than patients with AKI from other causes [51]. A different study demonstrated an 8.3% GFR decline at 1-year in COVID-19 AKI survivors [52]. Patients with long-COVID without AKI during hospitalisation also had increased risks of ESKD and major adverse kidney events [53]. Inflammatory changes and immune dysfunction following SARS-CoV-2 infection might have contributed [54].

Our study is one of the first describing the changing epidemiology of AKI and KRT in critically ill patients with COVID-19 [17,18,19, 55]. The strengths are the granular patient-level data, use of both SCr and urine output criteria to define AKI, and inclusion of short- and long-term kidney outcomes up to 90 days. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first study that explores the impact of fluid status on risk of COVID associated AKI in critically ill patients.

Despite these strengths, we acknowledge some limitations. First, this is a single-centre study using only routinely available laboratory and clinical data. About 40% of all patients were transferred from other institutions, either due to clinical needs (e.g. need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) or capacity. However, decisions to initiate COVID-19 therapies were based on national guidance. Second, only association but no causality can be implied. Unmeasured confounding factors and treatment bias might not have been accounted for in the models. Third, we did not have data regarding social deprivation status, which could have impacted AKI occurrence. Fourth, we collected detailed FB data, including diuretic use, but data pre-ICU admission were not available for all patients. To assess the association between FB and risks of new AKI and KRT, we focused on patients who had AKI or received KRT 48 h after admission to ICU. Fifth, we followed current consensus recommendations to estimate baseline renal function in patients with missing values. We acknowledge that this may have overestimated baseline function but note that a recent study showed comparable AKI adjudication and outcomes by using either true baseline SCr or SCr results on admission [56]. Sixth, we did not routinely perform urinalysis and did not use novel renal biomarkers during the pandemic and therefore cannot comment on their role in COVID associated AKI. We also did not perform any kidney biopsies and do not know the underlying histopathology. Finally, we acknowledge that both vaccination and evolving virus variants may have modified the AKI and KRT incidences [57]. Unfortunately, complete data regarding patients’ vaccination status and SARS-CoV-2 variants were not available to us. However, during the first two waves, either alpha or delta variant accounted for all ICU infections and milder variants (e.g. omicron) were only present in late 2021.

In summary, although patients in wave 2 were more vulnerable, i.e. older and frailer, we observed reduced rates of AKI and KRT. This decline may be due to changes in inflammatory status along with improved COVID-19 management including lower cumulative FB and changes in respiratory support. Future studies should explore the impact of new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, new immunomodulatory therapies, and vaccination on AKI and KRT requirement and long-term kidney outcomes. Finally, whether current therapies under investigation for long COVID syndrome impact the development of CKD after AKI will need to be investigated.

Our analysis confirms the changing epidemiology of AKI and KRT among critically ill COVID-19 patients with a trend towards less severe and shorter AKI and better long-term prognosis in the second wave. These changes occurred in parallel with decreased initiation of MV, application of lower PEEP and lower daily cumulative FB.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease-19

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- ECMO:

-

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- ESKD:

-

End-stage kidney disease

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- FB:

-

Fluid balance

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- KDIGO:

-

Kidney diseases: improving global outcomes

- KRT:

-

Kidney replacement therapy

- MDRD:

-

Modification of diet in renal disease

- MV:

-

Mechanical ventilation

- NIV:

-

Non-invasive ventilation

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- PEEP:

-

Positive end-expiratory pressure

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SCr:

-

Serum creatinine

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- WBC:

-

White blood cells

References

Lobo SM, Creutzfeldt CJ, Maia IS, Town JA, Amorim E, Kross EK, Çoruh B, Patel PV, Jannotta GE, Lewis A, et al. Perceptions of critical care shortages, resource use, and provider well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of 1,985 health care providers in Brazil. Chest. 2022;161:1526–42.

Montani D, Savale L, Noel N, Meyrignac O, Colle R, Gasnier M, Corruble E, Beurnier A, Jutant EM, Pham T, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Eur Respir Rev. 2022;31(163):210185.

Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(25):2451–60.

Greco M, De Corte T, Ercole A, Antonelli M, Azoulay E, Citerio G, Morris AC, De Pascale G, Duska F, Elbers P, et al. Clinical and organizational factors associated with mortality during the peak of first COVID-19 wave: the global UNITE-COVID study. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(6):690–705.

Shang Y, Pan C, Yang X, Zhong M, Shang X, Wu Z, Yu Z, Zhang W, Zhong Q, Zheng X, et al. Management of critically ill patients with COVID-19 in ICU: statement from front-line intensive care experts in Wuhan, China. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):73.

Ostermann M, Lumlertgul N, Forni LG, Hoste E. What every intensivist should know about COVID-19 associated acute kidney injury. J Crit Care. 2020;60:91–5.

Joseph A, Zafrani L, Mabrouki A, Azoulay E, Darmon M. Acute kidney injury in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):117.

Lumlertgul N, Tunstell P, Watts C, Hanks F, Cameron L, Tovey L, Masih V, McRobbie D, Srisawat N, Hart N, et al. In-house production of dialysis solutions to overcome challenges during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(1):200–6.

Yang L, Li J, Wei W, Yi C, Pu Y, Zhang L, Cui T, Ma L, Zhang J, Koyner J, et al. Kidney health in the COVID-19 pandemic: an umbrella review of meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Front Public Health. 2022;10: 963667.

Geri G, Darmon M, Zafrani L, Fartoukh M, Voiriot G, Le Marec J, Nemlaghi S, Vieillard-Baron A, Azoulay E. Acute kidney injury in SARS-CoV2-related pneumonia ICU patients: a retrospective multicenter study. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):86.

Lumlertgul N, Pirondini L, Cooney E, Kok W, Gregson J, Camporota L, Lane K, Leach R, Ostermann M. Acute kidney injury prevalence, progression and long-term outcomes in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a cohort study. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):123.

Xu J, Xie J, Du B, Tong Z, Qiu H, Bagshaw SM. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with severe COVID-19 induced acute kidney injury. J Intensive Care Med. 2021;36(3):319–26.

Chan L, Chaudhary K, Saha A, Chauhan K, Vaid A, Zhao S, Paranjpe I, Somani S, Richter F, Miotto R, et al. AKI in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(1):151–60.

Bayrakci N, Özkan G, Şakaci M, Sedef S, Erdem İ, Tuna N, Mutlu LC, Yildirim İ, Kiraz N, Erdal B, et al. The incidence of acute kidney injury and its association with mortality in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 followed up in intensive care unit. Ther Apher Dial. 2022;26:889.

Grimaldi D, Aissaoui N, Blonz G, Carbutti G, Courcelle R, Gaudry S, Gaultier A, D’Hondt A, Higny J, Horlait G, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of acute respiratory distress syndrome related to COVID-19 in Belgian and French intensive care units according to antiviral strategies: the COVADIS multicentre observational study. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):131.

Yu Y, Xu D, Fu S, Zhang J, Yang X, Xu L, Xu J, Wu Y, Huang C, Ouyang Y, et al. Patients with COVID-19 in 19 ICUs in Wuhan, China: a cross-sectional study. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):219.

Charytan DM, Parnia S, Khatri M, Petrilli CM, Jones S, Benstein J, Horwitz LI. Decreasing incidence of acute kidney injury in patients with COVID-19 critical illness in New York City. Kidney international reports. 2021;6(4):916–27.

Diebold M, Martinez AE, Adam KM, Bassetti S, Osthoff M, Kassi E, Steiger J, Pargger H, Siegemund M, Battegay M, et al. Temporal trends of COVID-19 related in-hospital mortality and demographics in Switzerland—a retrospective single centre cohort study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2021;151: w20572.

Sullivan MK, Lees JS, Drake TM, Docherty AB, Oates G, Hardwick HE, Russell CD, Merson L, Dunning J, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 from the ISARIC WHO CCP-UK Study: a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37(2):271–84.

Hoogenboom WS, Pham A, Anand H, Fleysher R, Buczek A, Soby S, Mirhaji P, Yee J, Duong TQ. Clinical characteristics of the first and second COVID-19 waves in the Bronx, New York: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2021;3: 100041.

ICNARC report on COVID-19 in critical care. https://www.icnarc.org/Our-Audit/Audits/Cmp/Reports.

Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120(4):c179-184.

Katayama S, Koyama K, Goto Y, Koinuma T, Tonai K, Shima J, Wada M, Nunomiya S. Body weight definitions for evaluating a urinary diagnosis of acute kidney injury in patients with sepsis. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):101.

Gupta S, Coca SG, Chan L, Melamed ML, Brenner SK, Hayek SS, Sutherland A, Puri S, Srivastava A, Leonberg-Yoo A, et al. AKI treated with renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients with COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(1):161–76.

Chawla LS, Bellomo R, Bihorac A, Goldstein SL, Siew ED, Bagshaw SM, Bittleman D, Cruz D, Endre Z, Fitzgerald RL, et al. Acute kidney disease and renal recovery: consensus report of the Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) 16 Workgroup. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(4):241–57.

Coca SG, King JT Jr, Rosenthal RA, Perkal MF, Parikh CR. The duration of postoperative acute kidney injury is an additional parameter predicting long-term survival in diabetic veterans. Kidney Int. 2010;78(9):926–33.

Messmer AS, Zingg C, Müller M, Gerber JL, Schefold JC, Pfortmueller CA. Fluid overload and mortality in adult critical care patients—a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(12):1862–70.

Inker LA, Astor BC, Fox CH, Isakova T, Lash JP, Peralta CA, Kurella Tamura M, Feldman HI. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(5):713–35.

Wan YI, Bien Z, Apea VJ, Orkin CM, Dhairyawan R, Kirwan CJ, Pearse RM, Puthucheary ZA, Prowle JR. Acute kidney injury in COVID-19: multicentre prospective analysis of registry data. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14:2356.

Zuo MZ, Huang YG, Ma WH, Xue ZG, Zhang JQ, Gong YH, Che L. Airway Management Chinese Society of Anesthesiology Task Force o: expert recommendations for tracheal intubation in critically ill patients with noval coronavirus disease 2019. Chin Med Sci J. 2020;35(2):105–9.

Cook TM, El-Boghdadly K, McGuire B, McNarry AF, Patel A, Higgs A. Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19: Guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the Association of Anaesthetists the Intensive Care Society, the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(6):785–99.

Brown CA 3rd, Mosier JM, Carlson JN, Gibbs MA. Pragmatic recommendations for intubating critically ill patients with suspected COVID-19. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1(2):80–4.

Brewster DJ, Chrimes N, Do TB, Fraser K, Groombridge CJ, Higgs A, Humar MJ, Leeuwenburg TJ, McGloughlin S, Newman FG, et al. Consensus statement: safe airway society principles of airway management and tracheal intubation specific to the COVID-19 adult patient group. Med J Aust. 2020;212(10):472–81.

Marini JJ, Gattinoni L. Management of COVID-19 respiratory distress. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2329–30.

Sherren PB, Camporota L, Sanderson B, Jones A, Shankar-Hari M, Meadows CI, Barrett N, Ostermann M, Hart N. Outcomes of critically ill COVID-19 patients managed in a high-volume severe respiratory failure and ECMO centre in the United Kingdom. J Intensive Care Soc. 2022;23(2):233–6.

Papoutsi E, Giannakoulis VG, Xourgia E, Routsi C, Kotanidou A, Siempos II. Effect of timing of intubation on clinical outcomes of critically ill patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of non-randomized cohort studies. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):121.

Ehrmann S, Li J, Ibarra-Estrada M, Perez Y, Pavlov I, McNicholas B, Roca O, Mirza S, Vines D, Garcia-Salcido R, et al. Awake prone positioning for COVID-19 acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure: a randomised, controlled, multinational, open-label meta-trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(12):1387–95.

Perkins GD, Ji C, Connolly BA, Couper K, Lall R, Baillie JK, Bradley JM, Dark P, Dave C, De Soyza A, et al. Effect of noninvasive respiratory strategies on intubation or mortality among patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and COVID-19: the RECOVERY-RS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;327(6):546–58.

Cottam D, Nadim MK, Forni LG. Management of acute kidney injury associated with COVID-19: what have we learned? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2021;30(6):563–70.

Holt DB, Lardaro T, Wang AZ, Musey PI Jr, Trigonis R, Bucca A, Croft A, Glober N, Peterson K, Schaffer JT, et al. Fluid resuscitation and progression to renal replacement therapy in patients with COVID-19. J Emerg Med. 2022;62(2):145–53.

Pickkers P, Darmon M, Hoste E, Joannidis M, Legrand M, Ostermann M, Prowle JR, Schneider A, Schetz M. Acute kidney injury in the critically ill: an updated review on pathophysiology and management. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(8):835–50.

Zhang J, Crichton S, Dixon A, Seylanova N, Peng ZY, Ostermann M. Cumulative fluid accumulation is associated with the development of acute kidney injury and non-recovery of renal function: a retrospective analysis. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):392.

Ostermann M, Straaten HM, Forni LG. Fluid overload and acute kidney injury: cause or consequence? Crit Care. 2015;19:443.

Hall A, Crichton S, Dixon A, Skorniakov I, Kellum JA, Ostermann M. Fluid removal associates with better outcomes in critically ill patients receiving continuous renal replacement therapy: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):279.

Chen JT, Ostermann M. Review of anti-inflammatory and antiviral therapeutics for hospitalized patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Crit Care Clin. 2022;38(3):587–600.

Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, Linsell L, Staplin N, Brightling C, Ustianowski A, Elmahi E, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693–704.

Shankar-Hari M, Vale CL, Godolphin PJ, Fisher D, Higgins JPT, Spiga F, Savovic J, Tierney J, Baron G, Benbenishty JS, et al. Association between administration of IL-6 antagonists and mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2021;326(6):499–518.

Orieux A, Khan P, Prevel R, Gruson D, Rubin S, Boyer A. Impact of dexamethasone use to prevent from severe COVID-19-induced acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):249.

van de Veerdonk FL, Giamarellos-Bourboulis E, Pickkers P, Derde L, Leavis H, van Crevel R, Engel JJ, Wiersinga WJ, Vlaar APJ, Shankar-Hari M, et al. A guide to immunotherapy for COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022;28(1):39–50.

COVID-19 rapid guideline: Managing COVID-19 [https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng191/resources/covid19-rapid-guideline-managing-covid19-pdf-51035553326].

Nugent J, Aklilu A, Yamamoto Y, Simonov M, Li F, Biswas A, Ghazi L, Greenberg J, Mansour S, Moledina D, et al. Assessment of acute kidney injury and longitudinal kidney function after hospital discharge among patients with and without COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3): e211095.

Gu X, Huang L, Cui D, Wang Y, Wang Y, Xu J, Shang L, Fan G, Cao B. Association of acute kidney injury with 1-year outcome of kidney function in hospital survivors with COVID-19: A cohort study. EBioMedicine. 2022;76: 103817.

Bowe B, Xie Y, Xu E, Al-Aly Z. Kidney outcomes in long COVID. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32(11):2851–62.

Chawla LS, Eggers PW, Star RA, Kimmel PL. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease as interconnected syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(1):58–66.

Roushani J, Thomas D, Oliver MJ, Ip J, Tang Y, Yeung A, Taji L, Cooper R, Magner PO, Garg AX, et al. Acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy in people with COVID-19 disease in Ontario, Canada: a prospective analysis of risk factors and outcomes. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(3):507–16.

Pickup L, Loutradis C, Law JP, Arnold JJ, Dasgupta I, Sarafidis P, Townend JN, Cockwell P, Ferro CJ. The effect of admission and pre-admission serum creatinine as baseline to assess incidence and outcomes of acute kidney injury in acute medical admissions. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021;37(1):148–58.

Lopez Bernal J, Andrews N, Gower C, Robertson C, Stowe J, Tessier E, Simmons R, Cottrell S, Roberts R, O’Doherty M, et al. Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines on covid-19 related symptoms, hospital admissions, and mortality in older adults in England: test negative case–control study. BMJ. 2021;373: n1088.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following colleagues Jom Bhumitrakul, Sophie Legg, Alison Li, Mitul Patel, Emma Karsten, Barnaby Sanderson, Andrew Nickson and Win Kulvichit who contributed to data collection and interpretation. We are also grateful to the critical care research nurses who helped with patient recruitment. Finally, we would like to express our gratitude towards all healthcare workers and allied professionals who looked after COVID-19 patients throughout all waves of the pandemic.

Funding

This study received research support from Baxter Healthcare Corporation and BioMérieux. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, data analysis, and interpretation of the data. An independent statistician monitored the raw data and the statistics. The publication was subject to review by internal employees from Baxter Healthcare Corporation prior to submission for protection of Confidential Information. However, the authors retain full responsibility for the analysis and content of this publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NL and MO are the guarantors for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. NL was responsible for study design, data collection, data analysis and data interpretation; MO was responsible for study design, study supervision, data analysis, and data interpretation and provided general oversight; KVD and YW were responsible for data analysis and data interpretation; EB, EP, JP, AJ and KW collected the data and contributed to the data interpretation; RL and NAB provided clinical input and helped interpreting the data. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and approved the final draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Research Authority and the Research Ethics Committee Health and Care Research Wales (REC Reference 20/WA/0175). Informed consent was obtained from the patients, personal, or professional consultee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MO received speaker honoraria from Baxter, Fresenius Medical and Biomerieux and research funding from Baxter, Fresenius, Biomerieux and LaJolla Pharma. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

: Figure S1: Number of patients admitted to ICU, patients with acute kidney injury, and patients who received kidney replacement therapy by month of admission. Figure S2: Proportions of patients with acute kidney injury and patients who received kidney replacement therapy by month of admission. Table S1: Baseline characteristics, laboratory biomarkers, treatment and outcomes by wave, AKI status and AKI staging. Table S2: Unadjusted associations between demographic characteristics and diagnosis of acute kidney injury for all patients and stratified by wave. Table S3: Indications for KRT between wave 1 and 2. Table S4: Adjusted associations between demographic characteristics and kidney replacement therapy for all patients and stratified by wave. Table S5: Comparison of daily cumulative fluid balance (%) by waves and sources of admission. Table S6: Unadjusted associations between COVID-19 treatments and AKI or KRT for all patients and stratified by wave. Table S7: Treatment and fluid balance for AKI or KRT patients only, stratified by day of diagnosis or KRT and wave of the pandemic. Table S8: Changes in serum creatinine and GFR values in alive patients from baseline, hospital discharge, and 90 days after hospital discharge Table S9: Associations between AKI, KRT and 24-hour cumulative fluid balance.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lumlertgul, N., Baker, E., Pearson, E. et al. Changing epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a prospective cohort. Ann. Intensive Care 12, 118 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-022-01094-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-022-01094-6