Abstract

Background

Organ dysfunction scores, based on physiological parameters, have been created to describe organ failure. In a general pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) population, the PEdiatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction-2 score (PELOD-2) score had both a good discrimination and calibration, allowing to describe the clinical outcome of critically ill children throughout their stay. This score is increasingly used in clinical trials in specific subpopulation. Our objective was to assess the performance of the PELOD-2 score in a subpopulation of critically ill children requiring plasma transfusions.

Methods

This was an ancillary study of a prospective observational study on plasma transfusions over a 6-week period, in 101 PICUs in 21 countries. All critically ill children who received at least one plasma transfusion during the observation period were included. PELOD-2 scores were measured on days 1, 2, 5, 8, and 12 after plasma transfusion. Performance of the score was assessed by the determination of the discrimination (area under the ROC curve: AUC) and the calibration (Hosmer–Lemeshow test).

Results

Four hundred and forty-three patients were enrolled in the study (median age and weight: 1 year and 9.1 kg, respectively). Observed mortality rate was 26.9 % (119/443). For PELOD-2 on day 1, the AUC was 0.76 (95 % CI 0.71–0.81) and the Hosmer–Lemeshow test was p = 0.76. The serial evaluation of the changes in the daily PELOD-2 scores from day 1 demonstrated a significant association with death, adjusted for the PELOD-2 score on day 1.

Conclusions

In a subpopulation of critically ill children requiring plasma transfusion, the PELOD-2 score has a lower but acceptable discrimination than in an entire population. This score should therefore be used cautiously in this specific subpopulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mortality is a frequent outcome in clinical trials in critically ill adults [1–5]. However, as mortality is lower in pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) patients [6–8], other outcome measures have been developed. Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), frequently observed in PICU, is a good candidate marker of severity of illness because MODS is the main cause of death in adult ICU [9] and in PICU patients [7]. MODS scores can be used to assess the presence and severity of organ dysfunction on admission and throughout the stay [9].

In a general PICU population, the PEdiatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction-2 score (PELOD-2) and the daily PELOD-2 scores had both a good discrimination and calibration, allowing to describe the clinical outcome of critically ill children throughout their stay [8, 10].

Little is known regarding plasma use in children. Our recent international observational study shows that non-bleeding patients represent more than half of the critically ill children receiving plasma transfusions [11]. This marked heterogeneity in plasma transfusion patterns might be due to the absence of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that could guide plasma transfusion strategies [12].

The first version of the PELOD score [7] has been used over the last few years as an outcome measure in studies in specific subpopulations, such as sepsis [13], hematopoietic stem cell transplant [14], acute respiratory dysfunction syndrome [15], extracorporeal life support [16], drowning [17], or seizure [18]. However, some authors have voiced their concern regarding using organ dysfunction scores in specific subpopulations [9].

Our hypothesis was that the PELOD-2 score would have the same performance in the subpopulation of patients receiving at least one plasma transfusion, validating its use as a surrogate outcome in a future RCT.

Our objective was to assess the performance of the PELOD-2 score in a subset of critically ill children requiring plasma transfusions [11] during their PICU stay.

Methods

Study sites and population

This is an ancillary study of a large point-prevalence study conducted in 101 PICUs in 21 countries. The complete methods have already been published elsewhere [11].

In brief, six 1-week periods were randomly predefined over six consecutive months (April to September 2014) for each study site. All critically ill children aged 3 days to 16 years old admitted to a participating PICU on one of the study days were considered eligible. Any eligible patient for whom at least one plasma transfusion was administered on any study day was included unless one of the exclusion criteria (i.e., plasmapheresis and gestational age less than 37 weeks at the time of PICU admission) was present. If a patient was readmitted within 24 h of PICU discharge, this was considered part of the same admission.

Variable of interest

The primary variable of interest of this analysis is the daily PELOD-2 scores [8, 10]. This score evaluates five organ functions using ten items: neurologic (Glasgow coma score and pupillary reaction), cardiovascular (lactatemia, mean arterial pressure), renal (creatinine), respiratory (PaO2/FiO2 ratio, PaCO2, invasive ventilation), and hematologic (white blood cell count and platelets). Data were collected on days 1 (i.e., the day of first transfusion), 2, 5, 8, and 12. These time points were previously identified as the first optimal time points to estimate the daily PELOD-2 scores [8, 10].

As for previously published severity and MODS scores, the most abnormal value of each variable observed during each of these time points was considered to calculate the PELOD-2 score. No laboratory tests were performed solely to meet the needs of this research; as recommended, a non-collected value was considered normal [8].

We also collected demographic data and PICU mortality, our primary outcome, which was censored 28 days after the end of the enrollment period.

Ethics approval

Ethics committees or boards at all 101 sites approved this study.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range (IQR), or proportions with their 95 % CI.

The association between PELOD-2 score and death was assessed by comparing the PELOD-2 score between survivors and non-survivors with a Mann–Whitney test. We also tested this association, adjusting for the baseline risk (PELOD-2 score at day 1) and the daily change in PELOD-2 score using a logistic regression model [10].

Discrimination refers to the ability of the score to separate non-survivors from survivors across the whole group [19]. We calculated the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of the PELOD-2 scores with its 95 % CI, for each time point. It is usually considered that an AUC of 1, 0.90–0.99, 0.80–0.89, 0.70–0.79, 0.60–0.69, and <0.60 is considered to be perfect, excellent, very good, good, moderate, and poor, respectively [20].

The calibration was assessed by directly comparing the observed and customized predicted mortality across subcategories of risk. We employed the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, where a p value >0.05 indicates acceptable calibration [20].

All tests were two sided, with an alpha level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 20 for Mac (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Population

Over the 30 study days, 13,192 patients were admitted and hence eligible and 443 (3.4 %) critically ill children receiving at least one plasma transfusion were included. The center which included the largest number of patients contributed to 11.1 % (49/443) of the results. Two hundred and fifty-three patients were from Europe, 134 from North America, and 56 from other continents.

The median age and weight were 1 year (IQR 0.2–6.4) and 9.1 kg (IQR 4.0–21.0), respectively. Forty-three percent were males. The main reasons for admission to PICU were respiratory (32 %), cardiac surgery with bypass (30 %), elective surgery (24 %), septic shock (15 %), emergency surgery (13 %), cardiac non-surgical (11 %), renal failure (10 %), and hepatic failure (10 %). Forty-eight patients (11 %) were on extracorporeal life support, and 35 patients (8 %) were on continuous renal replacement therapy. The full demographic description is available elsewhere [11].

The primary indication for plasma transfusion was critical bleeding in 22 % of patients, minor bleeding in 21 %, planned surgery or procedure in 12 %, and high risk of postoperative bleeding in 11 %. No bleeding or planned procedures were reported in 34 % of patients.

Median length of mechanical ventilation was 5 days (IQR 1–16), and median PICU length of stay was 10 days (IQR 4–24). The median time to death was 6 days (IQR 1;17).

PELOD-2 score

PELOD-2 score was collected in all patients on day 1 and in all surviving patients still in the PICU at posttransfusion days 2, 5, 8, and 12. There were no missing data.

Median PELOD-2 scores were statistically different between survivors and non-survivors: 7 (5;9) versus 10 (7;15) on transfusion day 1 (p < 0.001), as well as on the other days (Table 1; Fig. 1).

The PELOD-2 score on day 1 was a significant prognostic factor: The odds ratio for death was 1.30 (95 % CI 1.22–1.39) for each PELOD-2 point. Similarly, the serial evaluation of the changes in the daily PELOD-2 scores from day 1, adjusted for baseline value (PELOD-2 at day 1), demonstrated a significant association with death, for each of the observation days (Table 2).

Discrimination

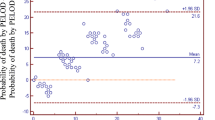

The AUC was 0.76 (95 % CI 0.71–0.81, Fig. 2) for day 1 and 0.78, 0.74, 0.74, and 0.77, for days 2, 5, 8, and 12, respectively (Table 3). Adding the INR to the PELOD-2 score resulted in an AUC of 0.77 (95 % CI 0.71–0.83). The AUC on day 1 according to plasma transfusion indication and according to the reason for admission is presented in Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

Calibration

The Hosmer–Lemeshow Chi-square value was 5.02 (p = 0.76) for PELOD-2 score on day 1. The results for the other time points, according to plasma transfusion indication, and according to the reason for admission are given in Tables 3, 4, and 5, respectively.

Adding the INR to the PELOD-2 score resulted in Hosmer–Lemeshow Chi-square value of 10.6 (p = 0.23).

Discussion

Our results indicate that in a subpopulation of critically ill children requiring plasma transfusions, the PELOD-2 score has an acceptable performance. These results of performance of the PELOD-2 scores are observed with the performance both according to the indications to plasma transfusion (Table 4) and according to the 5 days of the PELOD-2 scores (Tables 2, 3).

The PELOD-2 score seems to have a lower, although acceptable discrimination power compared to a general PICU population, where it had an excellent discrimination power, based on an AUC of 0.93. As the PELOD-2 score has been advocated to be “used as a surrogate outcome measure in randomized clinical trials” [7, 8], many recent trials have used these scores to assess patients [13–18]. As these studies enrolled only specific PICU subpopulations, their results should be interpreted cautiously, in light of our findings. Similar caveats have been made for adult organ dysfunction scores regarding their use in specific subpopulations [9].

The lower discrimination of the PELOD-2 score in a subset of critically ill children transfused with plasma might be explained by different observations. First, our population was sicker than the initial PELOD-2 study, with a mortality rate of 26.9 versus 6.0 %. The PICU length of stay was also longer (10 vs. 2 days), as the case-mix was different: In our population compared to the PELOD-2 population, the reasons for admission were less frequently respiratory (32 vs. 47 %, p < 0.001) and more frequently cardiovascular (64 vs. 19 %, p < 0.001) or hepatic (10 vs. 1 %, p < 0.001) [8]. Moreover, in the study of Pollack et al. (10,078 patients from U.S. PICUs), the mortality rate was 2.7 %, with a median age of 3.7 years and a median hospital length of stay of 4.9 days (PICU length of stay was not provided) [21]. The fact that all patients received plasma transfusions might also explain this lower discrimination, as observational studies have suggested that plasma transfusions were independently associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality [9, 22–24], but neither coagulopathy nor plasma transfusions are items of the PELOD-2 score. Third, except for mechanical ventilation, PELOD-2 score does not take into account the support that can be offered for each organ, such as vasoactive drugs, continuous renal replacement therapies, or extracorporeal life support (ECLS). Given that the mortality rate associated with ECLS is close to 50 % [25, 26], one could hypothesize that a lower discrimination may be due at least partly to the fact that PELOD-2 score does not take this variable into account. Similarly, the PELOD-2 score does not incorporate coagulopathy, which might be associated with increased risk of bleeding or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, which are also known to be associated with increased mortality [27].

As observed in the validation study, severity of illness is a major component to evaluate the performance of the daily PELOD-2 scores [10]. Therefore, in this study, the serial evaluation of the change in the daily PELOD-2 score has to be adjusted to the baseline value (PELOD-2 score on day 1). Our results indicate that changes in the PELOD-2 score over time are also associated with changes in the probability of death. These are important findings, as they validate the use of sequential measuring of the PELOD-2 score to assess clinical outcome. These results also highlight the relationship between organ failure and death.

Some limitations must be recognized. First, our results are only applicable to critically ill children requiring plasma transfusions and not to other PICU subpopulations. Second, our study days were not days after admission but days after plasma transfusion. It is of note, however, that the median length of PICU stay before the first plasma transfusion was 1 day. Third, although scores have classically been evaluated by their association with mortality, they might still adequately describe the clinical situation related to organ failure, as it has solid physiological basis and is clinically meaningful. Therefore, the ability of the PELOD-2 score to describe organ failure and its change over time might be more important that its ability to predict death. Fourth, additional variables to the PELOD-2 score could have been evaluated. Unfortunately, some interesting variables, such as platelet count, were not available in our database. However, adding the INR to the PELOD-2 score did not improve its performance.

Conclusions

In a subpopulation of critically ill children requiring plasma transfusion, the PELOD-2 score has a lower but acceptable discrimination than in an entire population. Although using this score as an outcome in a RCT seems reasonable, it should be interpreted cautiously.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- ECLS:

-

extracorporeal life support

- FiO2 :

-

inspired fraction of oxygen

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- MODS:

-

multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- PaO2 :

-

partial pressure of arterial oxygen

- PaCO2 :

-

partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide

- PELOD-2:

-

PEdiatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction-2 score

- PICU:

-

pediatric intensive care unit

References

Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368–77.

Ferguson ND, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Mehta S, Hand L, Austin P, et al. High-frequency oscillation in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(9):795–805.

Young D, Lamb SE, Shah S, MacKenzie I, Tunnicliffe W, Lall R, et al. High-frequency oscillation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(9):806–13.

Asfar P, Meziani F, Hamel JF, Grelon F, Megarbane B, Anguel N, et al. High versus low blood-pressure target in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(17):1583–93.

Lacroix J, Hebert PC, Fergusson DA, Tinmouth A, Cook DJ, Marshall JC, et al. Age of transfused blood in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(15):1410–8.

Pollack MM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE. PRISM III: an updated pediatric risk of mortality score. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(5):743–52.

Leteurtre S, Martinot A, Duhamel A, Proulx F, Grandbastien B, Cotting J, et al. Validation of the paediatric logistic organ dysfunction (PELOD) score: prospective, observational, multicentre study. Lancet. 2003;362(9379):192–7.

Leteurtre S, Duhamel A, Salleron J, Grandbastien B, Lacroix J, Leclerc F, et al. PELOD-2: an update of the PEdiatric logistic organ dysfunction score. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(7):1761–73.

Vincent JL, Bruzzi de Carvalho F. Severity of illness. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31(1):31–8.

Leteurtre S, Duhamel A, Deken V, Lacroix J, Leclerc F, Groupe Francophone de Reanimation et Urgences Pediatriques. Daily estimation of the severity of organ dysfunctions in critically ill children by using the PELOD-2 score. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):324.

Karam O, Demaret P, Shefler A, Leteurtre S, Spinella PC, Stanworth SJ, et al. Indications and effects of plasma transfusions in critically ill children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(12):1395–402.

Karam O, Tucci M, Combescure C, Lacroix J, Rimensberger PC. Plasma transfusion strategies for critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; (12):CD010654. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010654.pub2.

Raj S, Killinger JS, Gonzalez JA, Lopez L. Myocardial dysfunction in pediatric septic shock. J Pediatr. 2014;164(1):72–7.e2.

Duncan CN, Lehmann LE, Cheifetz IM, Greathouse K, Haight AE, Hall MW, et al. Clinical outcomes of children receiving intensive cardiopulmonary support during hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14(3):261–7.

Orwoll BE, Spicer AC, Zinter MS, Alkhouli MF, Khemani RG, Flori HR, et al. Elevated soluble thrombomodulin is associated with organ failure and mortality in children with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): a prospective observational cohort study. Crit Care. 2015;19:435.

Rambaud J, Guellec I, Leger PL, Renolleau S, Guilbert J. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for neonatal and pediatric refractory septic shock. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2015;19(10):600–5.

Mtaweh H, Kochanek PM, Carcillo JA, Bell MJ, Fink EL. Patterns of multiorgan dysfunction after pediatric drowning. Resuscitation. 2015;90:91–6.

Payne ET, Zhao XY, Frndova H, McBain K, Sharma R, Hutchison JS, et al. Seizure burden is independently associated with short term outcome in critically ill children. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 5):1429–38.

Shann F. Are we doing a good job: PRISM, PIM and all that. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(2):105–7.

Keegan MT, Gajic O, Afessa B. Severity of illness scoring systems in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(1):163–9.

Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Funai T, Dean JM, Berger JT, Wessel DL, et al. The pediatric risk of mortality score: update 2015. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(1):2–9.

Karam O, Lacroix J, Robitaille N, Rimensberger PC, Tucci M. Association between plasma transfusions and clinical outcome in critically ill children: a prospective observational study. Vox Sang. 2013;104(4):342–9.

Khan H, Belsher J, Yilmaz M, Afessa B, Winters JL, Moore SB, et al. Fresh-frozen plasma and platelet transfusions are associated with development of acute lung injury in critically ill medical patients. Chest. 2007;131(5):1308–14.

Sarani B, Dunkman WJ, Dean L, Sonnad S, Rohrbach JI, Gracias VH. Transfusion of fresh frozen plasma in critically ill surgical patients is associated with an increased risk of infection. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(4):1114–8.

Barbaro RP, Odetola FO, Kidwell KM, Paden ML, Bartlett RH, Davis MM, et al. Association of hospital-level volume of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation cases and mortality. Analysis of the extracorporeal life support organization registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(8):894–901.

Bokman CL, Tashiro J, Perez EA, Lasko DS, Sola JE. Determinants of survival and resource utilization for pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the United States 1997–2009. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(5):809–14.

Levi M, Ten Cate H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(8):586–92.

Authors’ contributions

All authors participated in the initial PlasmaTV study. OK and SL designed this ancillary study. OK, AD, and SL analyzed the data. OK and SL drafted the manuscript, and all authors participated in the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the PlasmaTV investigators for their tremendous work. We would also like to thank the Plateforme de Recherche Clinique of the Department of Pediatrics, Geneva University Hospital, for their help with this study.

Competing interests

Dr. Spinella reports personal fees from Octapharma and personal fees from Entegrion. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Due to regulations in some countries, we are unfortunately not authorized to provide the dataset.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The primary submission was approved by the Commission Cantonale d’Ethique de la Recherche (protocol GE 13-206). Ethics committees or boards at all 101 sites then individually approve this study.

Funding

This study was funded by the Groupe Francophone de Réanimation et Urgences Pédiatriques (GFRUP) and the Marisa Sophie Research Foundation for Critically Ill Children.

PlasmaTV investigators

Australia: Warwick Butt, Carmel Delzoppo, Kym Bain (Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne); Simon Erickson, Nathan Smalley (Princess Margaret Hospital for Children, Perth; Tavey Dorofaeff, Debbie Long (Royal Children’s Hospital, Brisbane); Nathan Smalley, Greg Wiseman (Townsville Hospital, Townsville). Belgium: Stéphan Clénent de Cléty, Caroline Berghe (Cliniquesuniversitaires Saint-Luc, Brussels); Annick de Jaeger (Princess Elisabeth Children’s University Hospital, Ghent); Pierre Demaret, Marc Trippaerts (CHC-CHR, Liège); Ariane Willems, ShancyRooze (Hôpitaluniversitaire des enfantsReine Fabiola, Brussels); Jozef De Dooy (Antwerp University Hospital, Edegem). Canada: Elaine Gilfoyle, Lynette Wohlgemuth (Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, AB); Marisa Tucci, Mariana Dumitrascu (CHU Sainte-Justine, Montréal, QC); Davinia Withington, Julia Hickey (Montreal Children’s Hospital, Montreal, QC); Karen Choong, Lois Sanders (McMaster Children’s Hospital, Hamilton, ON); Gavin Morrison (IWK Health Centre, Halifax, NS); Janice Tijssen (Children’s Hospital, London Health Sciences Centre, London, ON); David Wensley, Gordon Krahn (British Columbia Children’s Hospital, Vancouver, BC); Marc-Andre Dugas, Louise Gosselin (Centre Mère Enfant Soleil, CHU de Québec, Québec, QC); Miriam Santschi (CHUS, Sherbrooke, QC). Chile: Bettina Von Dessauer, Nadia Ordenes (Hospital De Niños Roberto Del Río, Santiago). Denmark: Arash Afshari, Lasse Hoegh Andersen, Jens Christian Nilsson, Mathias Johansen, Anne-Mette Baek Jensen (Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen). Ecuador: Santiago Campos Mino, Michelle Grunauer (Hospital de los Valles, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito. France: Nicolas Joram (Hôpital mère enfant, Nantes); Nicolas Roullet-Renoleau (Hôpital Gatien de Clocheville, CHU Tours, Tours); Etienne Javouhey, Fleur Cour-Andlauer, Aurélie Portefaix (Hôpital Femme Mère Enfant, Hospices Civils de Lyon, Lyon); Olivier Brissaud, Julie Guichoux (Hôpital des Enfants, Bordeaux); Valérie Payen (CHU Grenoble, Grenoble); Pierre-Louis Léger (Hôpital Armand-Trousseau, Paris); Mickael Afanetti (Hopitaux Pédiatriques CHU Lenval, Nice); Guillaume Mortamet (Hopital Necker, Paris); Matthieu Maria (Hôpital d’Enfants CHRU de Nancy, Nancy); Audrey Breining (Hopitaux Universitaires de Strasbourg, Strasbourg); Pierre Tissieres (Hôpital Kremlin-Bicêtre, Paris); Aimée Dorkenoo (CHU Lille, Lille); Anna Deho (Hopital Robert Debré, Paris). Germany: Harry Steinherr (MedizinischeHochschule Hannover, Hannover). Greece: Filippia Nikolaou (Athens Children Hospital P&A Kyriakou, Athens). Italy: Anna Camporesi (Children Hospital VittoreBuzzi, Milano); Federica Mario (Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Padua). Japan: Tatsuya Kawasaki, Shinya Miura (Shizuoka Children’s Hospital, Shizuoka City). New Zealand: John Beca, Miriam Rea, Claire Sherring, Tracey Bushell (Starship Children’s Hospital, Auckland). Norway: Gunnar Bentsen (Oslo University Hospital—Rikshospitalet, Oslo). Portugal: Alexandra Dinis (Hospital Pediátrico—CHUC, Coimbra); Gabriela Pereira (UCIP Hospital Dona Estefânia, Lisbon); Marisa Vieira (Hospital de Santa Maria, Lisbon); Marta Moniz (Hospital Prof. Dr Fernando Fonseca, Amadora). Saudi Arabia: Saleh Alshehri (King Saud Medical City, Riyadh); Manal Alasnag, Ahmad Rajab (King Fahd Armed Forces Hospital, Jeddah). Slovakia: Maria Pisarcikova (DFN Kosice, Kosice). Spain: Iolanda Jordan (Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona); Joan Balcells (Hospital Valld’Hebron, Barcelona); Antonio Perez-Ferrer, Jesús de Vicente Sánchez, Marta Vazquez Moyano (La Paz University Hospital, Madrid); Antonio Morales Martinez (Malaga Regional University Hospital, Malaga); Jesus Lopez-Herce, Maria Jose Solana (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid); Jose Carlos Flores González (Puerta del Mar University Hospital, Cadiz); Maria Teresa Alonso (Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla); Manuel Nieto Faza (Hospital Universitario Cruces, Bilbao). Switzerland: Marie-Hélène Perez, Vivianne Amiet (CHUV, Lausanne); Carsten Doell (Kinderspital Zürich, Zürich); Alice Bordessoule (Geneva University Hospital, Geneva). The Netherlands: Suzan Cochius-den Otter, Berber Kapitein (Erasmus MC—Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam); Martin Kneyber (Beatrix Children’s Hospital, Groningen). United Kingdom: Joe Brierley, Vanessa Rea, Stephen McKeever (Great Ormond Street, London); Andrea Kelleher (Royal Brompton Hospital, London); Barney Scholefield, Anke Top, Nicola Kelly, SatnamVirdee (Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham); Peter Davis, Susan George (Bristol Royal Hospital for Children, Bristol); Kay C. Hawkins, Katie McCall, Victoria Brown (Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, Manchester); Kim Sykes (University Hospital Southampton, Southampton); Richard Levin, Isobel MacLeod (Yorkhill Children’s Hospital, Glasgow); Marie Horan, PetrJirasek (Alder Hey Children’s hospital, Liverpool); David Inwald, Amina Abdulla, Sophie Raghunanan (Imperial College Healthcare, London); Bob Taylor (Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children, Belfast); Alison Shefler, Hannah Sparkes (Oxford University Hospitals, Oxford). USA: Sheila Hanson, Katherine Woods, David Triscari, Kathy Murkowski (Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI); Caroline Ozment (Duke University, Durham, NC); Marie Steiner, Dan Nerheim, Amanda Galster (University of Minneapolis, Minneapolis, MN); Renee Higgerson, LeeAnn Christie (Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, TX); Philip C. Spinella, Daniel Martin, Liz Rourke (Washington University in St. Louis, Saint Louis, MO); Jennifer Muszynski, Lisa Steele, (Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH); Samuel Ajizian, Michael C. McCrory (Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC); Kevin O’Brien, Christopher Babbitt, Erin Felkel, Glenn Levine (Miller Children’s Hospital Long Beach, Long Beach, CA); Edward J. Truemper, Machelle Zink (Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, Omaha, NE); Marianne Nellis (NYPH—Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY); Neal J. Thomas, Debbie Spear (Penn State Hershey Children’s Hospital, Hershey, PA); Barry Markovitz, Jeff Terry, Rica Morzov (Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA); Vicki Montgomery, Andrew Michael, Melissa Thomas (University of Louisville and Kosair Children’s Hospital, Louisville, KY); Marcy Singleton, Dean Jarvis, Sholeen Nett (Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH); Douglas Willson, Michelle Hoot (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA); Melania Bembea, Alvin Yiu (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD); David McKinley, Elizabeth Scarlett, Jennifer Sankey, Minal Parikh (Geisinger, Danville, PA); E. Vincent S. Faustino (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT); Kelly Michelson, Jay Rilinger, Laura Campbell (Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL); Shira Gertz (Hackensack University Medical Center, Hackensack, NJ); Jill M. Cholette (University of Rochester, Rochester, NY); Asumthia Jeyapalan (Holtz Children’s Hospital-Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami, FL); Margaret Parker (Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY); Scot Bateman, Amanda Johnson (UMass Memorial Children’s Medical Center, Worcester, MA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Karam, O., Demaret, P., Duhamel, A. et al. Performance of the PEdiatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction-2 score in critically ill children requiring plasma transfusions. Ann. Intensive Care 6, 98 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-016-0197-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-016-0197-6