Abstract

Key message

In mixed stands of Pinus pinaster and Pinus pinea, fewer insect vectors of the pinewood nematode (PWN) were captured than in pure P. pinaster stands. This finding has practical implications for PWN disease management, including the recommendation to improve the diversity of maritime pine plantations and to conserve stone pines in infected areas.

Context

The PWN is an invasive species in European pine forests, being vectored by the longhorn beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis. The presence of less preferred host trees may disrupt the insect vector dispersal and slow the spread of the disease.

Aims

The aim of the study was to compare the abundance of M. galloprovincialis in pure stands of Pinus pinaster, a preferred host tree, pure P. pinea stands, a less preferred host, and mixtures of these two species.

Methods

We selected 20 mature pine stands varying in % P. pinaster and % P. pinea in Spain. In each stand, we installed 3 pheromone traps to catch M. galloprovincialis. We related trap catches to stand and landscape composition.

Results

The level of capture of M. galloprovincialis was highest in pure P. pinaster stands and decreased with increasing proportion of P. pinea.

Conclusions

The presence of stone pine mixed with maritime pine significantly reduces the local abundance of the PWN insect vector. The most plausible mechanism is that P. pinea emits odors that have a repulsive effect on dispersing beetles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.1 Introduction

The pinewood nematode (PWN) Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Steiner and Buhrer) is one of the worst threats to coniferous forests in Europe. It is known to cause massive tree mortality wherever it has been established as in Japan, Korea, China, and more recently in Portugal (Rodrigues et al. 2015). It has been introduced several times in Spain but has been successfully eradicated so far (https://gd.eppo.int/reporting/article-6227). Like most invasive pest species, it is very difficult to control. All stages of the invasion process must therefore be taken into account in a holistic manner to try to limit its impacts, from its transport and introduction in a new area, its establishment and proliferation, to its spread across the country (Chapple et al. 2012). In this context, the status of host or non-host plant for the invasive pest is crucial because it is relevant to each of these steps. The list of host plants is used to identify the pathways of the transport of goods or commodities that support the stages of dissemination of the non-native species (Meurisse et al. 2019). Surveillance and detection are more effective when applied to habitats of the host plants. The most common method of eradication of non-native pests is host plant removal (Liebhold and Kean 2019). A promising method of non-native pest control relies on the mixtures of host and non-host plant species to enhance associational resistance effects (Guyot et al. 2015). Moreover, the presence of patches of non-host species can slow the spread of invasive pests (Rigot et al. 2014; Nunes et al. 2021).

In all countries where it is present or has been introduced, the pinewood nematode is carried and transmitted by longhorn beetles of the genus Monochamus. In Europe, it has so far only been detected in Monochamus galloprovincialis (Olivier) (Naves et al. 2015). The question of which host plant to monitor and possibly to remove in order to eradicate the pinewood nematode is therefore primarily concerned with the host plants of its insect vector. Common European pine species like maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Aït.), black pine (Pinus nigra Arnold), Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.), and Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) are well-established host trees of the pine sawyer beetle M. galloprovincialis (Appendix). However, the status of the stone (or umbrella) pine Pinus pinea (L.) as host of M. galloprovincialis is more doubtful (EFSA, 2012). In a laboratory choice test, adult M. galloprovincialis fed on fresh shoots of P. pinea, but it was the least preferred European pine species (Naves et al. 2006). In the same experiment, oviposition tests in the lab showed that very few eggs were laid on P. pinea bolts, and no offspring emerged from the bolts (Naves et al. 2006). In another laboratory experiment, Sanchez-Husillos et al. (2013) observed regular feeding on fresh P. pinea twigs (although always less than on twigs of other main European pine species). They also obtained some emergences of young adults from P. pinea logs, but less than 15% of egg laying resulted in the emergence of offspring on P. pinea. In a non-choice test in the laboratory, M. galloprovincialis was also found to be able to feed on 2-year-old potted pine trees with no significant difference between P. pinea and P. pinaster (Gonçalves et al. 2020). Yet, although Portugal has large areas of stone pine forests (www.euforgen.org) and the nematode has been present there for more than 20 years (Mota et al. 1999), no pinewood nematode dieback and no major attack of M. galloprovincialis have ever been reported on P. pinea in this country. Discrepancies between the results of laboratory experiments and in natura observations may occur and be due to differences in pine sawyer behavior in the lab and the field or the sensitivity/attractiveness of mature living trees compared to laboratory plants. Surprisingly, no field experiments have been conducted to date to address these questions.

To fill this knowledge gap, we developed a field trial in the Valladolid area (Castilla y León, Spain) where P. pinea and P. pinaster co-occur in large mature forests. In particular, we were interested in testing the hypothesis that the presence of P. pinea in mixed P. pinaster stands would reduce trap catch levels compared to catches in nearby pure P. pinaster forests, and that this reduction was proportional to the percentage of P. pinea in the mixture.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study area and stand selection

The study was set up in a forest region south of Valladolid, in the center of Spain. The forests in this region are dominated by pine forests composed of pure P. pinea stands, pure P. pinaster stands, and mixtures of these two species. The management of these stands is focused on production of edible pine seeds and resin in P. pinea or P. pinaster stands, respectively. The region has a continental climate and sandy soils. The PWN has never been detected in this region.

Within this region, we selected three sectors (see Fig. 1). Within each sector, we selected four or eight pine stands varying in their relative proportion of P. pinaster and P. pinea, from 0 to 100 % (i.e., pure P. pinaster stands, pure P. pinea stands, and mixtures of both in various proportions). In total, 20 stands were selected. P. pinaster stands have in general a higher tree density than P. pinea stands, but since the latter tree species has a denser and bigger canopy, we considered that light conditions in both stand types were comparable. Stand management includes removal of dead trees within 1 or 2 years maximum. The amount of dead trees was not measured but was in any case very low and similar between stand types. There was no resin collection in the selected P. pinaster stands. The age of the different stands was similar, ranging from 60 to 80 years.

Map of the study area with position of trap triplets, buffers of 800 m radius (red circles), the three sectors A, B, C (black line for the joint 2 km buffers), and the forest composition. The red square on the map of Spain (top-right map) indicates the localization of the study area. The coordinates of the center of sector A are 41.5028801 and −4.73272942; sector B 41.20447729 and −4.71737119, and C 41.32691005 and −4.54603389, in decimal degrees WGS84

2.2 Insect sampling

In each stand, three pheromone traps (Cross Vane® type; Alvarez et al. 2015a) were positioned with a mean distance of 80–100 m between traps, which is comparable to the attraction range of these traps (90–125 m, Jactel et al. 2019). Only four traps, in four different stands, were located at 100 m from the forest edge; all other traps were at more than 200 m from the edge. Traps were attached 2 m high on metal poles, at about 10 m from the nearest tree.

The 60 traps were installed on 22–24 May 2019 and equipped with attractive Galloprotect 2D lures for M. galloprovincialis (Alvarez et al. 2016). These lures contain two bark beetle kairomones (ipsenol and 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol) and the pheromone monochamol (2-undecyloxy-1-ethanol). The traps were emptied every 2 to 3 weeks until 25 October 2019, and the dispensers were changed twice (26 July and 11 September). The trap collection cup contained an insecticide to kill the beetles, but no liquid. For the analyses we used, the number of M. galloprovincialis beetles per sex and per trap cumulated over the whole season. Trap catches can be considered a proxy for the abundance of the insect vector during the flight season.

2.3 Tree composition at different scales around the traps

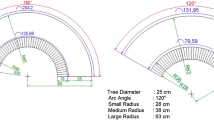

We characterized the pine tree composition at different scales around the traps using a GIS (QGIS 3.16.7, QGIS Development Team). We created buffers of 50 m to 800 m around traps, to analyze at which spatial scale a possible effect of tree composition on beetle catches might play a role.

We created around each trap a 50 m radius circular buffer to estimate the tree species composition in the direct surroundings of the traps. We counted within this buffer the number of P. pinaster trees and P. pinea trees using aerial photographs from 2018. The two pine species clearly differ in their crown shape and can therefore be recognized on aerial photos, which was confirmed by several field visits. For each 50 m buffer, we calculated then the % P. pinea among the total number of trees (the sum of P. pinea and P. pinaster equaled 100%, no other tree species being present in the sampled plots). We also counted the number of trees of the two pine species in a larger buffer of 200 m radius, created around the center of the three traps per stand. To characterize the tree composition at different landscape scales, we created buffers of 400 m, 600 m, and 800 m radii around the center of each trap triplet. We used land cover maps of the third Spanish forest inventory, which provided for each forest stand the percentage of the three most abundant tree species. This inventory was carried out between 1997 and 2007, so we verified on aerial photos of 2018 the composition of the stands. We calculated the % P. pinea and % P. pinaster in each buffer. For that, we estimated the surface covered by a given pine species by multiplying, for each forest stand intercepted by the buffer, the % of the pine species in that stand by the surface of that stand included in the buffer. Then, we summed up all the surfaces covered by each pine species and divided it by the buffer area to obtain the % cover of each pine species. For each buffer size separately, the % P. pinea and % P. pinaster were negatively correlated. The % P. pinea in the 50 m buffer was positively correlated with the % P. pinea in the 200, 400, 600, and 800 m buffer (see Table 2 and 3 in Appendix ). The composition of the landscape in the buffers was largely dominated by pine stands (P. pinaster or P. pinea), which represented 100%, 97%, 94%, and 91% of the buffer area for the 200 m, 400 m, 600 m, and 800 m buffers, respectively.

Finally, we created around each trap a 2 km radius buffer and joined these buffers per sector, creating one map per sector (Fig. 1). We calculated the % P. pinea and % P. pinaster for each of the three sectors using the same method as for the landscape buffers. The % P. pinea and % P. pinaster varied between the three sectors. The % P. pinea was 52.4%, 36.3%, and 24.1% for sectors A, B, and C respectively, and the % P. pinaster was 26.2%, 31.5%, and 35.6% for sectors A, B, and C, respectively. This resulted in a pinea/pinaster ratio of 2.0, 1.1, and 0.7, respectively. The remaining area of each sector was occupied by other land uses, mostly agricultural land (Fig. 1).

2.4 Analyses

We started the analyses at the 50-m scale and analyzed the effect of the following variables on the number of M. galloprovincialis beetles caught per trap: sex (as factor: male, female), % P. pinea, and the interaction sex*% P. pinea. To select the most appropriate model, we first compared three different types of models based on count data with these explanatory variables: a generalized linear mixed model (glmm) with a Poisson error structure and two glmm models with a negative binomial error structure (i.e., linear or quadratic parameterization (Hardin & Hilbe, 2007)). Comparison between models was based on the value of the Akaike’s information criterion corrected for small sample sizes (AICc). Next, we compared the best of these three models based on count data with a linear mixed model (Gaussian error structure) on log-transformed count data of beetles (natural logarithm plus one). Since AIC values cannot be compared between models with transformed and non-transformed response data, we visually checked various assumptions (normality of residuals, normality of random effects, linear relationship, homogeneity of variance, multicollinearity) between these two models, using the R package “performance.”

We used mixed models to take into account the experimental set up, where we had count data of males and females for the same trap, where three traps were positioned in the same stand, and where stands were in three different sectors. We therefore added a random effect of trap within stand within sector to all models. The model structure thus takes into account the overlapping buffers for the three traps per stand.

Among the three models based on count data, the two models with the negative binomial error distribution had the lowest AICc values (AICc 776.4 and 778.3) compared to the Poisson model (AICc 782.5). Comparison of the residuals of the glmm with the negative binomial error distribution and the lmm model on log-transformed data showed that the latter had a better distribution of residuals, and this Gaussian model was therefore used in the analyses.

Next, we used for the selected model type a model simplification procedure removing nonsignificant variables while applying marginality principle, where the principal effects were not removed if involved in a significant interaction. We visually checked model residuals of the selected model. For the best model, R2 values were calculated to estimate the variance explained by fixed effects (marginal R2, R2m) and by fixed plus random effects (conditional R2, R2c) (Nakagawa and Schielzeth, 2013). We ran these models for different buffer sizes (up to 800 m) to analyze if the effect observed differed with buffer size.

Since we had very different beetle catches between sectors, we ran the same model as selected above but including sector and the interaction term between sector and % P. pinea in the fixed part of the model. This allowed us to analyze if the same effect of % P. pinea on beetle captures was observed in each sector (i.e., no significant interaction between sector and % P. pinea).

All analyses were carried out in R 4.1.2 (R Core Team, 2021). The following functions and libraries were used: package “glmmTMB” for mixed models, package “performance,” and “see” for model residuals, function r.squaredGLMM from package “MuMin” for calculation of R2 and ANOVA from package “car” or significance of selected variables. The dataset used for the analyses is available in a repository (Van Halder et al. 2022).

3 Results

We captured a total of 2707 M. galloprovincialis beetles in the 60 traps, 1289 males and 1418 females. The number of beetles varied between 0 and 146 individuals per trap, with a mean of 45.1 individuals.

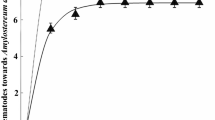

For the Gaussian model with the % P. pinea measured in a buffer of 50 m, we retained all variables, i.e., % P. pinea, sex, and their interaction, since the interaction was significant. The marginal and conditional R2 of this model were respectively 0.221 and 0.931. There was a significant negative effect of % P. pinea at 50 m on the number of M. galloprovincialis trapped (Table 1), with very low captures in pure stands of P. pinea (Fig. 2). The variable sex was included in the model but was not significant. The significant interaction between % P. pinea and sex indicated a more important negative effect of % P. pinea for males than for females (Fig. 2).

For the different buffer sizes up to 600 m, the results were comparable to the model with the buffer of 50 m. Only at 800 m the interaction between sex and % P. pinea was no longer significant. The R2m values increased slightly with buffer size (Table 1).

In the model including sector and the interaction sector*% P. pinea, variables retained in the selected model were % P. pinea, sex, sector, and the interaction % P. pinea*sex. The marginal and conditional R2 of this model were respectively 0.724 and 0.934. There was a significant effect of sector (χ2 44.9, P < 0.0001) with fewer catches in sector A (with the greatest pinea/pinaster ratio) than in sectors B or C (no significant difference between them, Figure 3 in Appendix), but no significant interaction between sector and % P. pinea. For this model, variable selection was comparable for the different buffer sizes (see Table 4 in Appendix).

4 Discussion

Our field experiment demonstrated a clear effect of native pine species composition on the trap captures of M. galloprovincialis, the insect vector of the pine wood nematode in southern Europe. The level of M. galloprovincialis captures in pheromone traps was high in pure mature P. pinaster stands, very low in pure mature P. pinea stands, and decreased in mixed forests of the two pine species with increasing proportion of P. pinea.

Two hypotheses, not mutually exclusive, can be proposed to explain the pattern of different capture levels of M. galloprovincialis as a function of the relative amount of the two pine species in the forests. They relate to the use of pine species as breeding substrate and/or emitter of chemical cues for the selection of suitable habitat.

First, one can assume that P. pinea emit odors that have a repellent effect on flying adults of M. galloprovincialis, reducing their probability of being attracted and caught by pheromone traps in P. pinea stands. Numerous studies have shown that herbivorous insects use the odors of their host plants as cues and more specifically that conifer beetles are strongly attracted by volatile terpenic compounds (Raffka 2014; Seybold et al. 2006; Tunset et al. 1993). For example, it has been shown that M. galloprovincialis is attracted by alpha pinene (Pajares et al. 2004; Ibeas et al. 2007), a monoterpenic compound. This compound is even used in attractive lures in combination with the pheromone (Alvarez et al. 2016). Conversely, non-host volatiles (NHVs) are used by insect herbivores as olfactory signals indicating the unsuitability of non-host plants or habitats (Zhang and Schlyter 2004; Campbell and Borden 2009). The main difference in the terpene profile of P. pinea compared to other European native pines is the high proportion of limonene (and the consequently low proportion of alpha and beta pinene) (Roussis et al. 1995; Rodrigues et al. 2017; Gaspar et al. 2020). Electrophysiological tests showed that limonene is well detected by the olfactory sensillae of the antennae of M. galloprovincialis (Alvarez et al. 2015b, 2016). Limonene is known as a common repellent or feeding deterrent for many conifer insects (Nordlander 1990; Ibrahim et al. 2001; Romón et al. 2017). In a laboratory bioassay, Sanchez-Husillos et al. (2013) showed that limonene applied to cut twigs of P. pinaster resulted in lower feeding activity by M. galloprovincialis than on control shoots. Limonene is also reported as a feeding deterrent for Monochamus alternatus, the insect vector of PWN in Asia (Fan and Sun 2006). In two field trials testing different combinations of pheromones and kairomones, the addition of limonene reduced the capture of M. galloprovincialis in pheromone traps by 25% and 46%, respectively (Alvarez et al. 2016). It is therefore likely that P. pinea trees do emit a high concentration of limonene into the atmosphere, and that this volatile monoterpene acts as a repellent for the pine sawyer beetle and/or as an odor masking the attractive alpha and beta pinene emitted by P. pinaster. Likewise, the higher catches in the pure P. pinaster stands may be linked with the attractive odors emitted by this tree species.

The second explanatory hypothesis for M. galloprovincialis capture patterns is that they reflect the amount of breeding resource, i.e., the quantity of P. pinaster, which is negatively correlated with the quantity of P. pinea. Several laboratory studies have shown that although M. galloprovincialis can feed on fresh shoots of P. pinea, the number of oviposition events on P. pinea trunks is lower than on P. pinaster, and the number of emerging offspring greatly reduced (Sanchez-Husillos et al. 2013) or zero (Naves et al. 2006). In our study, the average level of capture of M. galloprovincialis should then be proportional to the amount of suitable breeding substrate, i.e., weakened P. pinaster trees, assumed to be correlated with the area of P. pinaster stands in the landscape. This is consistent with the observations in the different buffers and with the much lower captures in sector A (9.8 individuals/trap) where the proportion of P. pinaster was lowest. However, the average number of catches per trap was higher in sector B (90.4) than in sector C (57.7), while they have a similar cover of P. pinaster (31.5% and 35.6%). Moreover, M. galloprovincialis has great flight capabilities, being able to travel several kilometers (David et al. 2014; Robinet et al. 2019). It is therefore virtually capable of covering the entire sector studied. It is also known that it does not respond to the attraction of the pheromone until it is sexually mature, which takes more than 2 weeks (Etxebeste et al. 2016; Robinet et al. 2019). If we suppose that M. galloprovincialis disperses from its emerging site and P. pinea and P. pinaster do not exert a repellent or attractive effect, then the beetles should have been found at a similar level of abundance in both P. pinea and P. pinaster stands of the same sector. In other words, if the main reason for the lower number of M. galloprovincialis captures in P. pinea stands was the lower amount of breeding substrate, this would imply that emerging insects remain for more than 15 days in the stand where they were produced. This seems less likely than the repellent effect of P. pinea (mediated by the release of limonene), but further experimentation will be necessary to decide between the relative contribution of the proposed hypotheses.

Interestingly, several recent studies have suggested that P. pinea is also more resistant or tolerant to the pine wood nematode B. xylophilus than other European pines like maritime or Scots pines (Nunes da Silva et al. 2015; Rodrigues et al. 2017; Pimentel et al. 2020). Recent laboratory studies have even shown that PWN-infected P. pinea saplings were able to reduce nematode infection to near zero (Estorninho et al. 2022). Additionally, Gaspar et al. (2020) found that the least infested P. pinaster trees had the highest concentration of limonene, while Liu et al. (2017) observed a higher limonene-synthase expression in resistant than in susceptible Masson pines (Pinus massoniana Lamb.).

We captured more females than males in our pheromone traps, which is consistent with the observation of the same biased sex ratio in traps baited with the same type of lure (Alvarez et al. 2016). This difference is likely due to the additional attraction of females by the aggregation pheromone emitted by M. galloprovincialis males. However, we lack information on the effect of limonene on the respective behavior of males and females. Thus, it is difficult to explain the significant interaction between the sex of trapped insects and the rate of P. pinea in pine plantations.

The two possible explanations we put forward to explain the pattern of lower M. galloprovincialis numbers in maritime pine and stone pine mixtures fit well with the theory of associational resistance (Jactel et al. 2021), which predicts lower abundance and damage of insect herbivores in mixed forests than in pure forests. According to the underlying host concentration hypothesis (Hambäck & Englund, 2005), specialized herbivorous insects, such as the pine sawyer beetle, would be more likely to immigrate, less likely to emigrate, and therefore spend more time feeding and breeding in habitat patches with a higher concentration of host resources, such as pure maritime pine stands. A second hypothesis, that of “host apparency,” states that host plants surrounded by heterospecific neighbors would be less apparent, i.e., more difficult to spot, locate, and colonize due to a disruption of visual (plants less tall than their non-host neighbors; Castagneyrol et al. 2013) or olfactory (neighbors emitting non-host volatiles; Jactel et al. 2011) cues used by insect herbivores to find a favorable host.

Our findings have two practical implications. First, the EU Commission implementing decision of 26 September 2012 on “emergency measures to prevent the spread within the Union of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus” requires precautionary felling of all susceptible plants in the infested zone and in a zone with a radius of 500 m around the plants infested with PWN, with all Pinus species considered “susceptible plants.” Here, we argue that it would be unnecessary to cut and remove P. pinea trees in a PWN-infected landscape because field observations in Portugal indicate that these trees do not develop pine wilt disease and seem not to be used for breeding by the insect vector while producing valuable ecosystem services. Secondly, as a preventive measure, it would be interesting to maintain or foster P. pinea regeneration or plantations to slow the spread of the PWN by repelling the insect vectors. P. pinaster stands could also be better protected by mixing them with P. pinea or by planting hedgerows of P. pinea around them (Dulaurent et al. 2012).

5 Conclusions

The number of M. galloprovincialis captures in pheromone traps was highest in P. pinaster stands and decreased with increasing proportion of P. pinea in mixed stands. This pattern can be due to a lower breeding resource, i.e., P. pinaster trees, by a repellent effect of P. pinea odors on the dispersal behavior of M. galloprovincialis, or by a combination of both mechanisms. Based on these results, we argue to conserve stone pines in PWN-infested areas, even in case of an eradication program, and to promote this tree species in forest landscapes within risk areas to slow the spread of the disease.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used for the current study is available at https://doi.org/10.15454/JXFGPI (van Halder et al. 2022).

References

Alvarez G, Ammagarahalli B, Hall DR, Pajares JA, Gemeno C (2015b) Smoke, pheromone and kairomone olfactory receptor neurons in males and females of the pine sawyer Monochamus galloprovincialis (Olivier) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). J Insect Physiol 82:46–55

Alvarez G, Etxebeste I, Gallego D, David G, Bonifacio L, Jactel H, Sousa E, Pajares JA (2015a) Optimization of traps for live trapping of pine wood nematode vector Monochamus galloprovincialis. J App Entomol 139:618–626

Alvarez G, Gallego D, Hall DR, Jactel H, Pajares JA (2016) Combining pheromone and kairomones for effective trapping of the pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis. J App Entomol 140:58–71

Campbell SA, Borden JH (2009) Additive and synergistic integration of multimodal cues of both hosts and non-hosts during host selection by woodboring insects. Oikos 118(4):553–563

Castagneyrol B, Giffard B, Péré C, Jactel H (2013) Plant apparency, an overlooked driver of associational resistance to insect herbivory. J Ecol 101(2):418–429

Chapple DG, Simmonds SM, Wong BB (2012) Can behavioral and personality traits influence the success of unintentional species introductions? Trends Ecol Evol 27(1):57–64

David G, Giffard B, Piou D, Jactel H (2014) Dispersal capacity of Monochamus galloprovincialis the European vector of the pine wood nematode on flight mills. J App Entomol 138(8):566–576

Dulaurent AM, Porte AJ, van Halder I, Vetillard F, Menassieu P, Jactel H (2012) Hide and seek in forests: colonization by the pine processionary moth is impeded by the presence of nonhost trees. Agricult Forest Entomol 14(1):19–27

EFSA Panel on Plant Health (PLH) (2012) Scientific opinion on the phytosanitary risk associated with some coniferous species and genera for the spread of pine wood nematode. EFSA J 2012 10(1):2553. [87 pp. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2553

Estorninho M, Chozas S, Mendes A, Colwell F, Abrantes I, Fonseca L, Fernandes P, Costa C, Máguas C, Correia O, Antunes C (2022) Differential impact of the pinewood nematode on Pinus species under drought conditions. Front Plant Sci 13:841707. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.841707

Etxebeste I, Sanchez-Husillos E, Álvarez G, Mas I, Gisbert H, Pajares J (2016) Dispersal of Monochamus galloprovincialis (Col: Cerambycidae) as recorded by mark–release–recapture using pheromone traps. J App Entomol 140(7):485–499

Euforgen (consulted in 2021) http://www.euforgen.org/species/pinus-pinea/

Fan JT, Sun JH (2006) Influences of host volatiles on feeding behaviour of the Japanese pine sawyer Monochamus alternatus. J App Entomol 130(4):238–244

Gaspar MC, Agostinho B, Fonseca L, Abrantes I, de Sousa HC, Braga MEM (2020) Impact of the pinewood nematode on naturally-emitted volatiles and scCO2 extracts from Pinus pinaster branches: a comparison with P. pinea. J Supercritical Fluids 159:104784

Gonçalves E, Figueiredo AC, Barroso JG, Henriques J, Sousa E, Bonifácio L (2020) Effect of Monochamus galloprovincialis feeding on Pinus pinaster and Pinus pinea oleoresin and insect volatiles. Phytochemistry 169:112159

Guyot V, Castagneyrol B, Vialatte A, Deconchat M, Selvi F, Bussotti F, Jactel H (2015) Tree diversity limits the impact of an invasive forest pest. PLoS One 10(9):e0136469

Hambäck PA, Englund G (2005) Patch area, population density and the scaling of migration rates: the resource concentration hypothesis revisited. Ecol Lett 8:1057–1065

Hardin JW, Hilbe JM (2007) Generalized linear models and extensions. Stata Press Publication, StatCorp LP, Texas

Ibeas F, Gallego D, Diez JJ, Pajares JA (2007) An operative kairomonal lure for managing pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis (Coleoptera: Cerymbycidae). J App Entomol 131(1):13–20

Ibrahim MA, Kainulainen P, Aflatuni A, Tiilikkala K, Holopainen JK (2001) Insecticidal repellent antimicrobial activity and phytotoxicity of essential oils: with special reference to limonene and its suitability for control of insect pests. Agricult Food Sci Finland 10:243–259

Jactel H, Birgersson G, Andersson S, Schlyter F (2011) Non-host volatiles mediate associational resistance to the pine processionary moth. Oecologia 166(3):703–711

Jactel H, Bonifacio L, Van Halder I, Vétillard F, Robinet C, David G (2019) A novel easy method for estimating pheromone trap attraction range: application to the pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis. Agricult Forest Entomol 21(1):8–14

Jactel H, Moreira X, Castagneyrol B (2021) Tree diversity and forest resistance to insect pests: patterns, mechanisms, and prospects. Annu Rev Entomol 66:277–296

Liebhold AM, Kean JM (2019) Eradication and containment of non-native forest insects: successes and failures. J Pest Sci 92(1):83–91

Liu Q, Wei Y, Xu L, Hao Y, Chen X, Zhou Z (2017) Transcriptomic profiling reveals differentially espressed genes associated with pine wood nematode resistance in masson pine (Pinus massonia Lamb). Sci Rep 7:4693

Meurisse N, Rassati D, Hurley BP, Brockerhoff EG, Haack RA (2019) Common pathways by which non-native forest insects move internationally and domestically. J Pest Sci 92(1):13–27

Mota MM, Braasch H, Bravo MA, Penas AC, Burgermeister W, Metge K, Sousa E (1999) First report of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus in Portugal and in Europe. Nematology 1(7):727–734

Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H (2013) A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Meth Ecol Evolut 4(2):133–142

Naves PM, Bonifacio L, Sousa E (2015) Nematode-Vector. In: Pine wilt disease in Europe: biological interactions and integrated management (ed by E Sousa F Vale and I Abrantes) pp 81–121, FNAPF Lisbon Portugal.

Naves PM, De Sousa EM, Quartau JA (2006) Feeding and oviposition preferences of Monochamus galloprovincialis for certain conifers under laboratory conditions. Entomol Exp Appl 120(2):99–104

Nordlander G (1990) Limonene inhibits attraction to α-pinene in the pine weevils Hylobius abietis and H. pinastri. J Chem Ecol 16(4):1307–1320

Nunes da Silva M, Solla A, Sampedro L, Zas R, Vasconcelos MW (2015) Susceptibility to the pinewood nematode (PWN) of four pine species involved in potential range expansion across Europe. Tree Physiol 35(9):987–999

Nunes P, Branco M, Van Halder I, Jactel H (2021) Modelling Monochamus galloprovincialis dispersal trajectories across a heterogeneous landscape to optimize monitoring by trapping networks. Landsc Ecol 36(3):931–941

Pajares JA, Ibeas F, Diez JJ, Gallego D (2004) Attractive responses by Monochamus galloprovincialis (Col Cerambycidae) to host and bark beetle semiochemicals. J App Entomol 128(9-10):633–638

Pimentel CS, McKenney J, Firmino PN, Calvão T, Ayres MP (2020) Sublethal infection of different pine species by the pinewood nematode. Plant Patho 69(8):1565–1573

Raffa KF (2014) Terpenes tell different tales at different scales: glimpses into the chemical ecology of conifer-bark beetle-microbial interactions. J Chem Ecol 40(1):1–20

R Core Team (2021) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. https://www.R-project.org/

Rigot T, Van Halder I, Jactel H (2014) Landscape diversity slows the spread of an invasive forest pest species. Ecography 37(7):648–658

Robinet C, David G, Jactel H (2019) Modeling the distances travelled by flying insects based on the combination of flight mill and mark-release-recapture experiments. Ecol Model 402:85–92

Rodrigues AM, Mendes MD, Lima AS, Barbosa PM, Ascensão L, Barroso JG, Figueiredo AC (2017) Pinus halepensis, Pinus pinaster, Pinus pinea and Pinus sylvestris essential oils chemotypes and monoterpene hydrocarbon enantiomers before and after inoculation with the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Chem Biodivers 14(1):e1600153

Rodrigues JM, Sousa E, Abrantes I (2015) Pine wilt disease historical review. In: Pine wilt disease in Europe: biological interactions and integrated management (ed by E Sousa F Vale and I Abrantes) pp 11–32 FNAPF Lisbon Portugal

Romón P, Aparicio D, Palacios F, Iturrondobeitia JC, Hance T, Goldarazena A (2017) Seasonal terpene variation in needles of Pinus radiata (Pinales: Pinaceae) trees attacked by Tomicus piniperda (Coleoptera: Scolytinae) and the effect of limonene on beetle aggregation. J Insect Sci 17(5)

Roussis V, Petrakis PV, Ortiz A, Mazomenos BE (1995) Volatile constituents of needles of five Pinus species grown in Greece. Phytochemistry 39(2):357–361

Sanchez-Husillos E, Alvarez-Baz G, Etxebeste IA, Pajares JA (2013) Shoot feeding oviposition and development of Monochamus galloprovincialis on Pinus pinea relative to other pine species. Entomol Exp Appl 149(1):1–10

Seybold SJ, Huber DP, Lee JC, Graves AD, Bohlmann J (2006) Pine monoterpenes and pine bark beetles: a marriage of convenience for defense and chemical communication. Phytochem Rev 5(1):143–178

Tunset K, Nilssen AC, Andersen J (1993) Primary attraction in host recognition of coniferous bark beetles and bark weevils (Col., Scolytidae and Curculionidae). J App Entomol, 115(1-5), 155-169.

Van Halder I, Sacristan A, Martín-García J, Pajares JA, Jactel H (2022) Monochamus galloprovincialis catches and pine tree composition in different landscape buffers in Spain. [dataset]. V1. Recherche Data Gouv repository. https://doi.org/10.15454/JXFGPI

Zhang QH, Schlyter F (2004) Olfactory recognition and behavioural avoidance of angiosperm nonhost volatiles by conifer-inhabiting bark beetles. Agricult Forest Entomol 6(1):1–20

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Bastien Castagneyrol for his valuable advice on statistical analyses.

Code availability

The R-code used for the analysis is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

This study was conducted in the framework of the HOMED project, which received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant 771271. This research was also part of the research project “Contención del nematodo del pino mediante el manejo de su insecto vector Monochamus galloprovincialis” (RTA2017-00012-C02-02) supported by Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades. The PhD student, Alberto Sacristan, received a grant (FPU17/01112) of the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HJ, JAP, and AS designed the study. AS did the site selection and fieldwork. IVH and HJ did the analyses and the first draft. HJ, IVH, AS, and JMG reviewed and edited the text. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The trapped Monochamus galloprovincialis beetles are not protected at a national or international level.

Consent for publication

The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Guest Editor: Christelle Robinet

In memory of the late colleague Juan Pajares.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 List of publications supporting the status of host plant for Monochamus galloprovincialis

Pinus nigra

Akbulut, S. (2009). Comparison of the reproductive potential of Monochamus galloprovincialis on two pine species under laboratory conditions. Phytoparasitica, 37(2), 125-135.

Akbulut, S., Keten, A., & Stamps, W. T. (2008). Population dynamics of Monochamus galloprovincialis Olivier (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in two pine species under laboratory conditions. Journal of pest science, 81(2), 115-121.

Akbulut, S., Keten, A., Baysal, I., & Yüksel, B. (2007). The effect of log seasonality on the reproductive potential of Monochamus galloprovincialis Olivier (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) reared in black pine logs under laboratory conditions. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 31(6), 413-422.

Inácio, M. L., Nobrega, F., Vieira, P., Bonifacio, L., Naves, P., Sousa, E., & Mota, M. (2015). First detection of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus associated with Pinus nigra in Portugal and in Europe. Forest pathology, 45(3), 235-238.

Jurc, M., Bojovic, S., Fernández, M. F., & Jurc, D. (2012). The attraction of cerambycids and other xylophagous beetles, potential vectors of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, to semio-chemicals in Slovenia. Phytoparasitica, 40(4), 337-349.

Jurc, M., Hauptman, T., Pavlin, R., & Borkovič, D. (2016). Target and non-target beetles in semiochemical-baited cross vane funnel traps used in monitoring Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (PWN) vectors in pine stands. Phytoparasitica, 44(2), 151-164.

Rassati, D., Toffolo, E. P., Battisti, A., & Faccoli, M. (2012). Monitoring of the pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis by pheromone traps in Italy. Phytoparasitica, 40(4), 329-336.

Bonifacio, L, Naves, P., Sousa, E. (2015) Vector plant. Pine Wilt Disease in Europe: Biological Interactions and Integrated Management (ed. by E. Sousa, F. Vale and I. Abrantes), pp. 125–157. FNAPF, Lisbon, Portugal

Pinus halepensis

Đođ, N., Lukić, I., Çota, E., & Pernek, M. (2016). Wood nematode species spectrum in the Mediterranean pine forests of Croatia. Periodicum biologorum, 117(4), 505-512.

Etxebeste, I., Sanchez-Husillos, E., Álvarez, G., Mas i Gisbert, H., & Pajares, J. (2016). Dispersal of Monochamus galloprovincialis (Col.: Cerambycidae) as recorded by mark–release–recapture using pheromone traps. Journal of applied entomology, 140(7), 485-499.

Ibeas, F., Gallego, D., Diez, J. J., & Pajares, J. A. (2007). An operative kairomonal lure for managing pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis (Coleoptera: Cerymbycidae). Journal of Applied Entomology, 131(1), 13-20.

Pajares, J. A., Álvarez, G., Ibeas, F., Gallego, D., Hall, D. R., & Farman, D. I. (2010). Identification and field activity of a male-produced aggregation pheromone in the pine sawyer beetle, Monochamus galloprovincialis. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 36(6), 570-583.

Pajares, J. A., Ibeas, F., Diez, J. J., & Gallego, D. (2004). Attractive responses by Monochamus galloprovincialis (Col., Cerambycidae) to host and bark beetle semiochemicals. Journal of Applied Entomology, 128(9-10), 633-638.

Bonifacio, L, Naves, P., Sousa, E. (2015) Vector plant. Pine wilt disease in Europe: Biological Interactions and Integrated Management (ed. by E. Sousa, F. Vale and I. Abrantes), pp. 125–157. FNAPF, Lisbon, Portugal.

Pinus sylvestris

Akbulut, S. (2009). Comparison of the reproductive potential of Monochamus galloprovincialis on two pine species under laboratory conditions. Phytoparasitica, 37(2), 125-135.

Akbulut, S., Keten, A., & Stamps, W. T. (2008). Population dynamics of Monochamus galloprovincialis Olivier (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in two pine species under laboratory conditions. Journal of pest science, 81(2), 115-121.

Akbulut, S., Keten, A., Baysal, I., & Yüksel, B. (2007). The effect of log seasonality on the reproductive potential of Monochamus galloprovincialis Olivier (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) reared in black pine logs under laboratory conditions. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 31(6), 413-422.

Foit, J., & Čermák, V. (2014). Colonization of disturbed S cots pine trees by bark-and wood-boring beetles. Agricultural and forest entomology, 16(2), 184-195.

Jurc, M., Bojovic, S., Fernández, M. F., & Jurc, D. (2012). The attraction of cerambycids and other xylophagous beetles, potential vectors of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, to semio-chemicals in Slovenia. Phytoparasitica, 40(4), 337-349.

Jurc, M., Hauptman, T., Pavlin, R., & Borkovič, D. (2016). Target and non-target beetles in semiochemical-baited cross vane funnel traps used in monitoring Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (PWN) vectors in pine stands. Phytoparasitica, 44(2), 151-164.

Naves PM, De Sousa EM & Quartau JA (2006b) Feeding and oviposition preferences of Monochamus galloprovincialis for certain conifers under laboratory conditions. Experimentalis et Applicata 120: 99–104.Entomologia

Rassati, D., Toffolo, E. P., Battisti, A., & Faccoli, M. (2012). Monitoring of the pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis by pheromone traps in Italy. Phytoparasitica, 40(4), 329-336.

Sanchez-Husillos, E., Etxebeste, I., & Pajares, J. (2015). Effectiveness of mass trapping in the reduction of Monochamus galloprovincialis Olivier (Col.: Cerambycidae) populations. Journal of Applied Entomology, 139(10), 747-758.

Sousa, E., Vale, F., & Abrantes, I. (Eds.). (2015). Pine wilt disease in Europe: Biological interactions and integrated management. Lisbon, Portugal: FNAPF.

Tomminen, J. (1992). The effects of beetles on the dispersal stages of Bursaphelenchus mucronatus Mamiya & Enda (Nematoda: Aphelenchoididae) in wood chips of Pinus sylvestris L. Entomologica Fennica, 3(4), 195-203.

Tomminen, J. (1993). Development of Monochamus galloprovincialis Olivier (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae) in cut trees of young pines (Pinus sylvestris L.) and log bolts in southern Finland. Entomologica Fennica, 4(3), 137-142.

Pinus pinaster

Álvarez, G., Etxebeste, I., Gallego, D., David, G., Bonifacio, L., Jactel, H., ... & Pajares, J. A. (2015). Optimization of traps for live trapping of Pine Wood Nematode vector Monochamus galloprovincialis. Journal of Applied Entomology, 139(8), 618-626.

Alvarez, G., Gallego, D., Hall, D. R., Jactel, H., & Pajares, J. A. (2016). Combining pheromone and kairomones for effective trapping of the pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis. Journal of applied entomology, 140(1-2), 58-71.

Alves, M., Pereira, A., Vicente, C., Matos, P., Henriques, J., Lopes, H., ... & Henriques, I. (2018). The role of bacteria in pine wilt disease: insights from microbiome analysis. FEMS microbiology ecology, 94(7), fiy077.

Branco, M., Bragança, H., Sousa, E., & Phillips, A. J. (2014). Pests and diseases in Portuguese forestry: current and new threats. In Forest context and policies in Portugal (pp. 117-154). Springer, Cham.

David, G., Giffard, B., Piou, D., & Jactel, H. (2014). Dispersal capacity of Monochamus galloprovincialis, the European vector of the pine wood nematode, on flight mills. Journal of Applied Entomology, 138(8), 566-576.

Etxebeste, I., Sanchez-Husillos, E., Álvarez, G., Mas i Gisbert, H., & Pajares, J. (2016). Dispersal of Monochamus galloprovincialis (Col.: Cerambycidae) as recorded by mark–release–recapture using pheromone traps. Journal of applied entomology, 140(7), 485-499.

Jactel, H., Bonifacio, L., Van Halder, I., Vétillard, F., Robinet, C., & David, G. (2019). A novel, easy method for estimating pheromone trap attraction range: application to the pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis. Agricultural and Forest Entomology, 21(1), 8-14.

Naves PM, De Sousa EM & Quartau JA (2006b) Feeding and oviposition preferences of Monochamus galloprovincialis for certain conifers under laboratory conditions. Experimentalis et Applicata 120: 99–104.Entomologia

Naves, P. M., Camacho, S., De Sousa, E. M., & Quartau, J. A. (2007). Transmission of the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus through feeding activity of Monochamus galloprovincialis (Col., Cerambycidae). Journal of Applied Entomology, 131(1), 21-25.

Naves, P. M., Camacho, S., De Sousa, E. M., & Quartau, J. A. (2006). Entrance and distribution of the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus on the body of its vector Monochamus galloprovincialis (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). Entomologia generalis, 29(1), 71-80.

Pajares, J. A., Ibeas, F., Diez, J. J., & Gallego, D. (2004). Attractive responses by Monochamus galloprovincialis (Col., Cerambycidae) to host and bark beetle semiochemicals. Journal of Applied Entomology, 128(9-10), 633-638.

Rassati, D., Toffolo, E. P., Battisti, A., & Faccoli, M. (2012). Monitoring of the pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis by pheromone traps in Italy. Phytoparasitica, 40(4), 329-336.

Sanchez-Husillos, E., Etxebeste, I., & Pajares, J. (2015). Effectiveness of mass trapping in the reduction of Monochamus galloprovincialis Olivier (Col.: Cerambycidae) populations. Journal of Applied Entomology, 139(10), 747-758.

Bonifacio, L, Naves, P., Sousa, E. (2015) Vector plant. Pine Wilt Disease in Europe: Biological Interactions and Integrated Management (ed. by E. Sousa, F. Vale and I. Abrantes), pp. 125–157. FNAPF, Lisbon, Portugal

Sousa, E., Bravo, M. A., Pires, J., Naves, P., Penas, A. C., Bonifácio, L., & Mota, M. M. (2001). Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Nematoda; aphelenchoididae) associated with Monochamus galloprovincialis (Coleoptera; Cerambycidae) in Portugal. Nematology, 3(1), 89-91.

Sousa, E., Naves, P., & Vieira, M. (2013). Prevention of pine wilt disease induced by Bursaphelenchus xylophilus and Monochamus galloprovincialis by trunk injection of emamectin benzoate. Phytoparasitica, 41(2), 143-148.

Torres-Vila, L. M., Zugasti, C., De-Juan, J. M., Oliva, M. J., Montero, C., Mendiola, F. J., ... & Espárrago, G. (2014). Mark-recapture of Monochamus galloprovincialis with semiochemical-baited traps: population density, attraction distance, flight behaviour and mass trapping efficiency. Forestry: An International Journal of Forest Research, 88(2), 224-236.

Vicente, C. S., Nascimento, F. X., Espada, M., Barbosa, P., Hasegawa, K., Mota, M., & Oliveira, S. (2013). Characterization of bacterial communities associated with the pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis, the insect vector of the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. FEMS microbiology letters, 347(2), 130-139.

Pinus pinea

Naves PM, De Sousa EM & Quartau JA (2006b) Feeding and oviposition preferences of Monochamus galloprovincialis for certain conifers under laboratory conditions. Experimentalis et Applicata 120: 99–104.Entomologia

Sanchez-Husillos, E., Alvarez-Baz, G., Etxebeste, I. A., & Pajares, J. A. (2013). Shoot feeding, oviposition, and development of Monochamus galloprovincialis on Pinus pinea relative to other pine species. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 149(1), 1-10.

Sanchez-Husillos, E., Etxebeste, I., & Pajares, J. (2015). Effectiveness of mass trapping in the reduction of Monochamus galloprovincialis Olivier (Col.: Cerambycidae) populations. Journal of Applied Entomology, 139(10), 747-758.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Halder, I., Sacristan, A., Martín-García, J. et al. Pinus pinea: a natural barrier for the insect vector of the pine wood nematode?. Annals of Forest Science 79, 43 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13595-022-01159-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13595-022-01159-3