Abstract

Objective

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) predominantly affects women, but previous studies suggest that men with SLE present a more severe disease phenotype. In this study, we investigated a large and well-characterized patient group with the aim of identifying sex differences in disease manifestations, with a special focus on renal involvement.

Methods

We studied a Swedish multi-center SLE cohort including 1226 patients (1060 women and 166 men) with a mean follow-up time of 15.8 ± 13.4 years. Demographic data, disease manifestations including ACR criteria, serology and renal histopathology were investigated. Renal outcome and mortality were analyzed in subcohorts.

Results

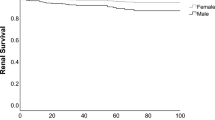

Female SLE patients presented more often with malar rash (p < 0.0001), photosensitivity (p < 0.0001), oral ulcers (p = 0.01), and arthritis (p = 0.007). Male patients on the other hand presented more often with serositis (p = 0.0003), renal disorder (p < 0.0001), and immunologic disorder (p = 0.04) by the ACR definitions. With regard to renal involvement, women were diagnosed with nephritis at an earlier age (p = 0.006), while men with SLE had an overall higher risk for progression into end-stage renal disease (ESRD) with a hazard ratio (HR) of 5.1 (95% CI, 2.1–12.5). The mortality rate among men with SLE and nephritis compared with women was HR 1.7 (95% CI, 0.8–3.8).

Conclusion

SLE shows significant sex-specific features, whereby men are affected by a more severe disease with regard to both renal and extra-renal manifestations. Additionally, men are at a higher risk of developing ESRD which may require an increased awareness and monitoring in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by multi-organ involvement, dysregulated autoantibody production, and activation of the type I interferon system [1,2,3,4,5]. Among the spectrum of chronic rheumatic diseases, SLE is one of the most overrepresented diseases in women [6], with a female to male ratio of 9–10:1 [7], only surpassed by primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) with a reported ratio of 9–20:1 [8, 9]. Notably, the pre-pubertal and post-menopausal female:male ratios of SLE are considerably lower ranging from 2 to 6:1 and 3–8:1, respectively, compared with those during child-bearing ages [10, 11]. This female preponderance has been widely accepted as a hallmark of SLE and most rheumatic diseases; however, the pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for the sexual dimorphism are still unclear. Many factors have been put forward as an attempt to explain this sex bias: intrinsic sex differences of the immune system [12], sex hormones [13], sex chromosomes [14], sex differences in gene regulation [15], sex-dependent environmental factors [16], and the gut microbiome [17], among others. The interaction and degree of contribution of these factors to the development of an autoimmune disorder is still poorly understood and, thus, an important field of research.

Strikingly, the sex differences in disease susceptibility also resonate at the clinical level, where women and men present distinctive features. Many studies performed in rheumatoid arthritis [18], multiple sclerosis [19], systemic sclerosis [20], and pSS [21, 22] have highlighted sex differences in disease presentation with regard to disease severity, symptoms or comorbidities. For instance, in pSS, men present with more extraglandular manifestations at the time of diagnosis than women [21], and have a higher frequency of lymphoma [22]. Taken together, this body of work suggests that men with rheumatic diseases, despite being less prone to develop them, tend to have a more severe disease phenotype.

In SLE, male sex has also been associated with a more severe form of the disease in terms of clinical manifestations and prognosis, with renal involvement and serological abnormalities such as hypocomplementemia and anti-dsDNA autoantibodies reported as more common in male patients [23]. Additionally, cardiovascular complications are more frequent among men with SLE, contributing to an overall increased organ damage accrual in these patients [24]. Further, male sex has been identified as a risk factor for premature death when diagnosed with SLE [25]. Whether there is a correlation between gender and long-term prognosis in patients with lupus nephritis has not been completely elucidated. While some studies have found male gender to be a risk factor for renal failure [26,27,28,29], there is inconsistency across studies, as several studies have not been able to detect such a correlation [30, 31]. This inconsistency could possibly be explained by the retrospective nature of the studies, small sample sizes, bias in referral and selection of the female controls [32]. Delay in diagnosis, health-seeking behavior, and poor treatment compliance in men has been proposed to account for a poorer prognosis in men [32]. Thus, although it is well-known that male sex confers a higher risk for lupus nephritis, there is a need for further studies to clarify whether male patients are also at a higher risk for more severe forms of lupus nephritis and worse outcome.

Hence, in the present study, we aimed at describing sex differences in the clinical presentation of SLE in a large and well-characterized group of patients with a special focus on renal involvement, a potentially severe manifestation observed more frequently among male patients. Further, we aimed at identifying relevant sex differences in the presentation and outcome of renal involvement, including histopathology, progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and mortality.

Patients and methods

Patients in the study

The study population consisted of 1226 patients (1060 women and 166 men) of the DISSECT program [22], out of which 1170 fulfilled at least 4 of the 1982 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria [33], and the additional 56 cases had a clinical diagnosis of SLE and fulfilled the Fries’ diagnostic principle for SLE [34]. No exclusion criteria were used. Of the patients for whom information on ethnicity was available, 93% were of European descent (908/976), with similar proportions in women (93%, 786/849) and men (96%, 122/127). Mean disease duration from diagnosis to last follow-up for the whole cohort was 15.4 ± 11.4 years; with 15.8 ± 11.6 years for the female group and 13.4 ± 10.2 years for the male group.

The patients were diagnosed and followed at the Departments of Rheumatology at the University Hospitals in Skåne, Linköping, Uppsala and the four most northern counties in Sweden, as well as the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden. Clinical data with regard to autoantibody status and disease manifestations including ACR criteria items [33], as well as renal histopathology, were retrieved from the patients’ medical records. The study protocol was approved by the regional ethical committee for the respective study center, and the patients gave informed consent.

Analysis of renal involvement

Data for in-depth analysis of renal involvement was available from a subgroup of the aforementioned SLE cohort. This consisted of 902 patients (780 women and 122 men) from the Departments of Rheumatology at the University Hospitals in Lund, Uppsala, Linköping and Stockholm.

Out of 322 patients with renal involvement, data regarding renal biopsy findings were available for 265 patients (199 female, 66 male). A renal biopsy was conducted in 81% of the female patients (199/247) and 88% of the male patients (66/75), and subsequent biopsies were taken if needed at different time points during the follow-up period. The biopsies were classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [35] or the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN-RPS) [36]. In addition, the biopsies were assessed for findings with vascular involvement as observed in anti-phospholipid syndrome-associated nephropathy (APSN) [37], a histological finding characterized by acute thrombotic lesions in glomeruli and/or arterioles (thrombotic microangiopathy) or more chronic vascular lesions in accordance with APSN. In cases with repeated biopsies, the most severe histopathological class is reported.

Further, data regarding progression of renal function impairment was analyzed in a subgroup of patients (the Stockholm cohort). ESRD was defined as reaching a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of less than 15 mL/min/1.73m2 (GFR < 15). Follow-up time was defined as the number of years from nephritis diagnosis to the last follow-up date. Information on time of death was based on patient charts or follow-up in population registers.

Statistical analysis

For comparison of continuous variables, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. The Chi-square test was used when analyzing categorical data, and Fisher’s exact test was employed if the observed frequency of any given cell was < 5 and/or the total number of analyzed individuals was < 40. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 6. Cox proportional hazard modeling was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) risk for ESRD and death after nephritis diagnosis, comparing males to females. Estimates were adjusted for age and SLE duration at the time of nephritis diagnosis. Data were analyzed using STATA MP 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). In all analyses, p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Sex differences in the fulfillment of ACR criteria

The study population consisted of 1226 SLE patients, out of which 87% were female (n = 1060) and 13% male (n = 166) (p < 0.0001, Table 1). Women were diagnosed at an age of 36 ± 15 years (mean, SD), whereas men were diagnosed at 40 ± 19 years of age (mean, SD) (p = 0.006). In the cohort, we first analyzed frequencies of the ACR classification criteria [33] items in female and male patients at the inclusion time point and observed significant sex differences in the frequencies of several organ manifestations. Male patients were significantly more often affected by serositis (p = 0.0003) (Table 2), both pleuritis and pericarditis (p = 0.02 and p = 0.004, respectively). Furthermore, fulfillment of the renal disorder criterion was significantly more common in men with SLE (p < 0.0001), as reflected by higher frequencies of proteinuria (p = 0.001) and cellular casts (p = 0.005). Men also presented more often with the immunologic disorder criterion (p = 0.04). On the other hand, female patients presented more frequently with malar rash, photosensitivity, oral ulcers and arthritis criteria (p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001, p = 0.01 and p = 0.007, respectively) (Table 2). Female and male SLE patients, however, did not differ in the number of fulfilled ACR classification criteria (Table 2).

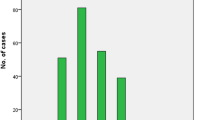

Sex differences in renal involvement and mortality

In 902 patients (122 men/780 women) for which clinical data for in-depth analysis of renal involvement were available, 75/122 (61%) of the men were diagnosed with renal involvement according to the ACR criteria for renal disease [33]. In contrast, only 247/780 (32%) of the women presented with renal involvement (p < 0.0001) (Table 3). Histopathological data from kidney biopsies were available for analysis in a subset of cases (n = 265/322 cases with renal involvement), and the majority of the cases presented features of lupus nephritis (Table 3). Interestingly, histopathological examination also revealed other types of renal involvement (APSN, vasculitis, IgA nephropathy, tubulointerstitial nephritis or diabetic nephropathy) in a smaller subset of SLE patients. No significant differences in the occurrence of these subtypes were observed between women and men. The histopathological examination revealed that most patients from both sexes had proliferative nephritis (WHO and/or ISN-RPS classification III or IV). In terms of the overall clinical presentation, renal involvement displayed, in some instances, a marked sexual dimorphism. Women were diagnosed with renal involvement at an earlier age (p = 0.006), although the timespan from SLE diagnosis to development of renal disease was not significantly different among the sexes (Table 3).

Furthermore, we analyzed renal outcome and mortality in a subcohort of patients with histopathologically verified renal involvement from the Karolinska University Hospital (n = 166) in which long-term follow-up data were retrieved until date. Importantly, after adjusting for age at diagnosis of renal involvement, analysis by Cox proportional hazard modeling demonstrated that men with SLE had a higher relative risk for development of ESRD, with a hazard ratio of 5.1 (95% CI, 2.1–12.5) (Tables 4 and 5). Further, the Cox modeling also revealed that men with SLE and renal involvement had a trend towards an increased death rate, HR 1.7 (95% CI, 0.8–3.8), in comparison with the corresponding female group.

Discussion

The cohort investigated here represents, up to this date, the study with the largest number of male patients ever included in an analysis of clinical sex differences in SLE. The sexual dimorphism in the clinical presentation of SLE has been previously acknowledged [23, 38,39,40,41], and based on our present findings, which confirm and extend results from prior publications, it is apparent that women with SLE are significantly more often affected by cutaneous manifestations while men present with a more severe spectrum of organ manifestations.

Renal disorder (proteinuria and/or presence of cellular casts) was observed significantly more often in men with SLE from our cohort, in accordance with previous findings [10, 42]. Lupus nephritis is one of the most severe disease manifestations of SLE; arising from an autoantibody-mediated glomerular inflammation, and dictated in part by a genetic susceptibility [43, 44]. Male SLE patients were not only more prone to present with renal involvement, but they were also more likely to progress into ESRD, a critical complication that can lead to increased mortality [45]. Notably though, the frequency of different histopathological subtypes did not differ between female and male patients. Previous studies have reported that impaired renal function, measured as decreased GFR, was one of the strongest risk factors for mortality in SLE patients [46]. The higher risk of ESRD among men could potentially be explained by other comorbidities such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, tobacco smoking, or hyperlipidemia, which could negatively affect the progression of the renal disease. However, such data were not available for analysis in the current study. We could also demonstrate a clear trend towards an increased mortality in men with renal involvement as compared with women. The lack of firm statistical significance may be explained by limitations in the sample size.

Currently, there are no proposed molecular mechanisms to explain this male propensity to present with renal manifestations. It is of note, though, that men from our cohort had more immunological disturbances. This enhanced humoral response in the male group could exacerbate the inflammation occurring in the renal tissue, contributing to the progression to ESRD observed in our cohort.

Overall, our results suggest a more severe phenotype in male SLE. In contrast to a recent publication [47], the majority of the patients in our study were of European descent, which entails that our findings could represent renal features specific for this population, but not necessarily other populations. In the study by Feldman et al. [47], data were collected from the Medicaid Program, which introduces a selection bias. One strength of the present study is that it includes a large set of unselected SLE patients, since the health care in Sweden ensures that all individuals are seen and diagnosed within the same system. This allows for inclusion in a population-based manner and a possibility for prompt follow-up of patients.

The increased frequency of serositis in male SLE has been recognized in previous studies, where male sex has been identified as a risk factor for the development of pleuritis, but not pericarditis [41, 48,49,50]. However, in our study, we found that both pleuritis and pericarditis occur more often in men. The male susceptibility for serositis is currently not well understood. Possibly, genetic polymorphisms could partly account for this manifestation. One example of how this may occur is a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in CXCR3 described by Im et al. [51], which is associated with pleuritis only in male SLE patients. The CXCR3 gene, situated on the X chromosome, encodes a chemokine receptor which interacts with CXCL9, CXCL10 and CXCL11. The polymorphism may modulate the chemokine axis, promoting a potential increase in lymphocyte migration into target tissues. This process might be enhanced in male SLE patients carrying this SNP on their only X chromosome and, thus, promote inflammation of the pleurae. In general, men with rheumatic diseases present more frequently with pulmonary complications. Rheumatoid pleuritis is more common in male than female patients [52], and men with pSS exhibit interstitial lung disease more frequently than female pSS patients [22]. Thus, it appears that the lung is a specially affected organ in male patients with systemic autoimmunity. Further studies shall aim to clarify the possible pathophysiological mechanisms involved in this sexually dimorphic feature.

On the other hand, several epidemiological studies [53, 54] have described a higher incidence and prevalence of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in women than men. As reported by Jarukitsopa et al. [54], the age-dependent presentation of cutaneous lupus manifestations might hint at a sex hormone-driven process, orchestrated by estrogens. Estrogen may play a crucial role in skin manifestations and flares in SLE and, therefore, have a more negative impact in women due to its higher levels than in men.

This study has several strengths, including the well-characterized SLE population, and the Swedish health care insurance system which offers equal service to all citizens, regardless of socioeconomic or geographic status and thus diminishes inclusion bias. Some limitations should also be mentioned. The participating clinics are tertiary referral centers, suggesting that the included patients may have a more severe disease phenotype than a general SLE study population. A tendency to not diagnose SLE in males may constitute a bias; SLE is known to be unusual among males, and milder skin and joint manifestations in males may potentially pass without specific diagnosis until more specific or obvious manifestations, such as serositis or proteinuria, become apparent.

Perspectives and significance

Our study highlights and corroborates the notion that male sex is associated with a more severe form of SLE, characterized by an increased propensity for certain phenotypes like serositis and renal disorder. Men with SLE presented more frequently with renal involvement and have a higher risk of progression to ESRD, and there appeared to be a trend towards a higher mortality rate in males with renal involvement. Conversely, women were more often affected by skin manifestations. The identification of these sex differences in SLE manifestations is crucial to raise awareness of a more severe disease course in male patients. This may be of importance in the clinical setting, allowing physicians to increase their surveillance, especially in male lupus patient with renal involvement.

Availability of data and materials

In concordance with the ethic approval and Swedish law, the data for this study cannot be shared to a third party.

References

Wahren-Herlenius M, Dorner T. Immunopathogenic mechanisms of systemic autoimmune disease. Lancet. 2013;382:819–31.

Hassan AB, Lundberg IE, Isenberg D, et al. Serial analysis of Ro/SSA and La/SSB antibody levels and correlation with clinical disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand J Rheumatol. 2002;31:133–9.

Pourmand N, Wahren-Herlenius M, Gunnarsson I, et al. Ro/SSA and La/SSB specific IgA autoantibodies in serum of patients with Sjogren's syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58:623–9.

Popovic K, Nyberg F, Wahren-Herlenius M, et al. A serology-based approach combined with clinical examination of 125 Ro/SSA-positive patients to define incidence and prevalence of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:255–64.

Eloranta ML, Ronnblom L. Cause and consequences of the activated type I interferon system in SLE. J Mol Med. 2016;94:1103–10.

Whitacre CC. Sex differences in autoimmune disease. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:777–80.

Danchenko N, Satia JA, Anthony MS. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of worldwide disease burden. Lupus. 2006;15:308–18.

Patel R, Shahane A. The epidemiology of Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:247–55.

Kvarnstrom M, Ottosson V, Nordmark B, et al. Incident cases of primary Sjogren’s syndrome during a 5-year period in Stockholm County: a descriptive study of the patients and their characteristics. Scand J Rheumatol. 2015;44:135–42.

Murphy G, Isenberg D. Effect of gender on clinical presentation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52:2108–15.

Simard JF, Sjowall C, Ronnblom L, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus prevalence in Sweden in 2010: what do national registers say? Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:1710–7.

Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:626–38.

McMurray RW, May W. Sex hormones and systemic lupus erythematosus: review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2100–10.

Liu K, Kurien BT, Zimmerman SL, et al. X chromosome dose and sex bias in autoimmune diseases: increased prevalence of 47,XXX in systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2016;68:1290–300.

Yao C, Joehanes R, Johnson AD, et al. Sex- and age-interacting eQTLs in human complex diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:1947–56.

Parks CG, De Roos AJ. Pesticides, chemical and industrial exposures in relation to systemic lupus Erythematosus. Lupus. 2014;23:527–36.

Gomez A, Luckey D, Taneja V. The gut microbiome in autoimmunity: sex matters. Clin Immunol. 2015;159:154–62.

Sokka T, Toloza S, Cutolo M, et al. Women, men, and rheumatoid arthritis: analyses of disease activity, disease characteristics, and treatments in the QUEST-RA study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R7.

Marrie RA, Patten SB, Tremlett H, et al. Sex differences in comorbidity at diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: a population-based study. Neurology. 2016;86:1279–86.

Hussein H, Lee P, Chau C, et al. The effect of male sex on survival in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:2193–200.

Ramirez Sepulveda JI, Kvarnstrom M, Brauner S, et al. Difference in clinical presentation between women and men in incident primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Biol Sex Differ. 2017;8:16.

Ramirez Sepulveda JI, Kvarnstrom M, Eriksson P, et al. Long-term follow-up in primary Sjogren’s syndrome reveals differences in clinical presentation between female and male patients. Biol Sex Differ. 2017;8:25.

Schwartzman-Morris J, Putterman C. Gender differences in the pathogenesis and outcome of lupus and of lupus nephritis. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:604892.

Andrade RM, Alarcon GS, Fernandez M, et al. Accelerated damage accrual among men with systemic lupus erythematosus: XLIV. Results from a multiethnic US cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:622–30.

Manger K, Manger B, Repp R, et al. Definition of risk factors for death, end stage renal disease, and thromboembolic events in a monocentric cohort of 338 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:1065–70.

Austin HA 3rd, Muenz LR, Joyce KM, et al. Prognostic factors in lupus nephritis. Contribution of renal histologic data. Am J Med. 1983;75:382–91.

Iseki K, Miyasato F, Oura T, et al. An epidemiologic analysis of end-stage lupus nephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;23:547–54.

de Carvalho JF. do Nascimento, AP, Testagrossa, LA, et al. Male gender results in more severe lupus nephritis. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1311–5.

Yu KH, Kuo CF, Chou IJ, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: a nationwide population-based study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2016;19:1175–82.

Al Arfaj AS, Khalil N, Al Saleh S. Lupus nephritis among 624 cases of systemic lupus erythematosus in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29:1057–67.

Mok CC, Wong RW, Lau CS. Lupus nephritis in southern Chinese patients: clinicopathologic findings and long-term outcome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34:315–23.

Mok CC. Prognostic factors in lupus Nephritis. Lupus. 2005;14:39–44.

Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–7.

Fries JF, Holman HR. Systemic lupus erythematosus: a clinical analysis. Major Probl Intern Med. 1975;6:v–199.

Churg J. Renal disease : classification and atlas of glomerular disease. 2nd ed. New York: Igaku-Shoin; 1995. p. 1–541.

Weening JJ, D'Agati VD, Schwartz MM, et al. The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. Kidney Int. 2004;65:521–30.

Tektonidou MG. Renal involvement in the antiphospholipid syndrome (APS)-APS nephropathy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2009;36:131–40.

Alonso MD, Martinez-Vazquez F, Riancho-Zarrabeitia L, et al. Sex differences in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus from Northwest Spain. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34:11–24.

Crosslin KL, Wiginton KL. Sex differences in disease severity among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Gend Med. 2011;8:365–71.

Lu LJ, Wallace DJ, Ishimori ML, et al. Review: male systemic lupus erythematosus: a review of sex disparities in this disease. Lupus. 2010;19:119–29.

Voulgari PV, Katsimbri P, Alamanos Y, et al. Gender and age differences in systemic lupus erythematosus. A study of 489 Greek patients with a review of the literature. Lupus. 2002;11:722–9.

Vozmediano C, Rivera F, Lopez-Gomez JM, et al. Risk factors for renal failure in patients with lupus nephritis: data from the spanish registry of glomerulonephritis. Nephron Extra. 2012;2:269–77.

Mohan C, Putterman C. Genetics and pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:329–41.

Bolin K, Sandling JK, Zickert A, et al. Association of STAT4 polymorphism with severe renal insufficiency in lupus nephritis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84450.

Mok CC, Kwok RC, Yip PS. Effect of renal disease on the standardized mortality ratio and life expectancy of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2154–60.

Gustafsson JT, Simard JF, Gunnarsson I, et al. Risk factors for cardiovascular mortality in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R46.

Feldman CH, Broder A, Guan H, et al. Sex differences in health care utilization, end-stage renal disease, and mortality among Medicaid beneficiaries with incident lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2018;70:417–26.

Aydintug AO, Domenech I, Cervera R, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in males: analysis of clinical and laboratory features. Lupus. 1992;1:295–8.

Font J, Cervera R, Navarro M, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in men: clinical and immunological characteristics. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:1050–2.

Liang Y, Leng RX, Pan HF, et al. The prevalence and risk factors for serositis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37:305–11.

Im CH, Park JA, Kim JY, et al. CXCR3 polymorphism is associated with male gender and pleuritis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum Immunol. 2014;75:466–9.

Balbir-Gurman A, Yigla M, Nahir AM, et al. Rheumatoid pleural effusion. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:368–78.

Durosaro O, Davis MD, Reed KB, et al. Incidence of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, 1965-2005: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:249–53.

Jarukitsopa S, Hoganson DD, Crowson CS, et al. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus and cutaneous lupus erythematosus in a predominantly white population in the United States. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67:817–28.

Acknowledgements

We thank Johanna Sandling for skillful management of data. Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council, the Heart-Lung Foundation, the Stockholm and Uppsala County Councils, Karolinska Institutet, Uppsala University, the Swedish Rheumatism association, the Swedish Society of Medicine, the Ingegerd Johansson donation, the Fund for Renal Research, and the King Gustaf the V:th 80-year foundation. The DISSECT study is supported by an AstraZeneca Science for Life Laboratory Research Collaboration grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

JIRS, IG and MWH conceived and designed the study. KB, DL, ES, AJ, GN, SRD, AAB, LR, CS, IG and the DISSECT consortium managed study participant recruitment and clinical data. The data was analyzed by JIRS and JM. JIRS, IG and MWH wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors participated in revision until its final stage. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

DISSECT consortium members.

Agneta Zickert, Stockholm; Albin Björk, Stockholm; Anders A. Bengtsson, Lund; Andreas Jönsen, Lund; Christine Bengtsson, Umeå; Christopher Sjöwall, Linköping; Helena Enocsson, Linköping; Jonas Wetterö, Linköping; Per Eriksson, Linköping; Dag Leonard, Uppsala; Elisabet Svenungsson, Stockholm; Guðný Ella Thorlacius, Stockholm; Gunnel Nordmark, Uppsala; Ingrid E. Lundberg, Stockholm; Iva Gunnarsson, Stockholm; Johanna K. Sandling, Uppsala; Jorge I. Ramírez Sepúlveda, Stockholm; Karin Bolin, Uppsala; Kerstin Lindblad-Toh, Uppsala; Lars Rönnblom, Uppsala; Leonid Padyukov, Stockholm; Lina Hultin-Rosenberg, Uppsala; Maija-Leena Eloranta, Uppsala; Marie Wahren-Herlenius, Stockholm; Solbritt Rantapää Dahlqvist, Umeå.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the regional ethical committee for the respective study center (Uppsala University 00–227 and 2016/155, Linköping University M75–08/2008, Lund University 2010/668, Karolinska Institutet 03–556, Umeå University/Northern Sweden 07–066 M) and for the DISSECT consortium (2015/450). The patients gave informed written or oral consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramírez Sepúlveda, J.I., Bolin, K., Mofors, J. et al. Sex differences in clinical presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus. Biol Sex Differ 10, 60 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-019-0274-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-019-0274-2