Abstract

Background

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease is defined as an inherited disorder characterized by renal cyst formation due to mutations in the PKD1 or PKD2 gene, whereas tuberous sclerosis complex is an autosomal dominant neurocutaneous syndrome caused by mutation or deletion of the TSC2 gene. A TSC2/PKD1 contiguous gene syndrome, which is caused by a chromosomal mutation that disrupts both the TSC2 and PKD1 genes, has been identified in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex and severe early-onset autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. The tumor tissue of patients with breast cancer with contiguous gene syndrome has a high mutation burden and produces several neoantigens. A diffuse positive immunohistochemistry staining for cluster of differentiation 8+ in the T cells of breast cancer tissue is consistent with neoantigen production due to high mutation burden.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old Japanese woman who had been undergoing dialysis for 23 years because of end-stage renal failure secondary to autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease was diagnosed as having triple-negative breast cancer and underwent mastectomy in 2015. She had a history of epilepsy and skin hamartoma. Her grandmother, mother, two aunts, four cousins, and one brother were also on dialysis for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Her brother had epilepsy and a brain nodule. Another brother had a syndrome of kidney failure, intellectual disability, and diabetes mellitus, which seemed to be caused by mutation in the CREBBP gene. Immunohistochemistry of our patient’s breast tissue showed cluster of differentiation 8 and programmed cell death ligand 1 positivity.

Conclusions

Programmed cell death ligand 1 checkpoint therapy may be effective for recurrence of triple-negative breast cancer in a patient with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and tuberous sclerosis complex.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), which is defined as an inherited disorder characterized by renal cyst formation, is caused by dysfunction of polycystin 1 or polycystin 2, which leads to mutations in the PKD1 or PKD2 gene, respectively. Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal dominant neurocutaneous syndrome that is caused by mutation or deletion of the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 2 (TSC2) gene, which encodes for tuberin. The PKD1 gene is adjacent to the TSC2 gene on chromosome 16p13.3. TSC2/PKD1 contiguous gene syndrome (CGS), which is caused by a chromosomal mutation that disrupts both the TSC2 and PKD1 genes, has been identified in patients with TSC and severe early-onset ADPKD [1]. Several reports characterized TSC2/PKD1 CGS as a severe polycystic kidney growth with onset and end-stage renal failure at an early age [2,3,4]. Therefore, patients with constitutional deletions involving the TSC2 and PKD1 genes were suggested to have poor prognosis of their renal function. Here, we presented the case of a 61-year-old Japanease woman with ADPKD, TSC, and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Gene deletion in tumor cells can lead to a high mutation burden, which can result in neoantigen production, as well as programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression. In the present case, immunohistochemical analysis indicated diffuse expressions of PD-L1 in the tumor and cluster of differentiation 8 (CD8)+ T around the tumor. Administration of an immune checkpoint inhibitor without chemotherapy may be considered when a patient who is undergoing dialysis develops cancer recurrence.

Case presentation

A 61-year-old Japanese woman (proband, III-10) (Fig. 1) had been undergoing dialysis for 23 years for end-stage renal failure secondary to polycystic kidney disease (PKD) (Fig. 2a), which was diagnosed in 2003. She had childhood epilepsy, as well as hypertension and skin hamartoma (Fig. 2b). She temporarily changed her residence after the nuclear power plant leak that was caused by the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami but later returned home. In 2015, she noticed stiffness in her right breast, which was biopsied and diagnosed as cancer, for which mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection was performed. The pathologic diagnosis at that time was invasive ductal carcinoma, stage IIA: tumor (T) 2, node (N) 0, metastasis (M) 0, lymphatic invasion (Ly) 0, venous invasion (V) 0, estrogen receptor (ER) (−), progesterone receptor (PgR) (−), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (−).

Reconstructed pedigree of the family with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Squares denote male family members, circles denote female family members, and solid symbols denote individuals affected by autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and undergoing kidney dialysis. The arrow denotes the proband, a symbol with a slash indicates a deceased person, and the diseases are listed below the symbols. BC breast cancer, D diverticulitis, DM diabetes mellitus, E epilepsy, H hamartoma, HT hypertension, KF kidney failure, L leukemia, N brain nodule, P proband, R intellectual disability

Her family history (Fig. 1) revealed a brother (III-13) who was on dialysis for 19 years for ADPKD (Fig. 3a), epilepsy, and a brain nodule (Fig. 3b); he died at 54 years of age. She had a younger brother (III-12) who had kidney failure, intellectual disability, and diabetes mellitus (DM). Her mother (II-6) received dialysis for ADPKD, had epilepsy, and died at an unknown age. Our patient’s aunt (II-1) received dialysis for 16 years for ADPKD and died at 78 years of age; our patient’s aunt’s son (III-3) had ADPKD and was receiving dialysis. Another aunt (II-2) was on dialysis for ADPKD; her son (III-4) was receiving dialysis for ADPKD and had hypertension and diverticulitis; her twin daughters (III-6 and III-8, respectively) were receiving dialysis for ADPKD. Our patient’s grandmother (I-1) received dialysis for ADPKD and died at an unknown age. At present, our patient is on dialysis without any sign of recurrence, and we recommended her children be tested.

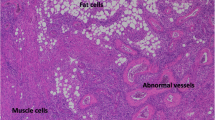

Evaluation of the resected breast cancer tissue by immunohistochemistry showed CD8+ T cells on the tumor–stromal interface (Fig. 4a) and PD-L1 expression on the membrane of tumor cells (Fig. 4b). The increased CD8 expression seemed to be associated with the high PD-L1 expression.

Immunohistochemistry for cluster of differentiation 8 and programmed cell death ligand 1. The infiltrating immune cells are immunohistochemically positive for a cluster of differentiation 8 and b programmed cell death ligand 1. a Cluster of differentiation 8 expression is detected using a mouse monoclonal antibody (clone C8/144B, catalog no. GA62361–2; Dako, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) (10 ×). b Programmed cell death ligand 1 expression is detected using a rabbit monoclonal antibody (clone E1L3N, catalog no. #13684; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) (10 ×)

Discussion

Mutation burden

The presence of TSC2 and PKD1 gene deletions should be considered in the clinical assessment of TSC in children with early-onset PKD and in all patients with ADPKD who develop end-stage renal failure prior to the fourth or fifth decade of life [5]. Dysfunction of the C-terminal tail of PKD1 in TSC2/PKD1 CGS was suggested to play a crucial role in renal prognosis [6].

Kleczko et al. suggested that T cells, specifically CD8+ T cells, had a functional role in ADPKD progression [7]. Therefore, the use of immune-oncology agents that target this pathway may represent a novel therapeutic approach for ADPKD [7]. First, patients with TSC2/PKD1 CGS have high mutation burden and produce several neoantigens, which are produced by cancer cells that have not been previously recognized by the immune system. Second, the neoantigens have very high immunologic potential, because they evade thymic selection and central tolerance. Finally, multiple gene deletions, as well as monogenic deficiency, induce the production of cytotoxic immune cells, such as CD8+ T cells, and infiltration of CD8+ T cells around the tumor leads to neoantigen production. Endometrial cancer with polymerase epsilon ultra-mutation and microsatellite instability hypermutation has been shown to have an active tumor microenvironment (TME) with increased numbers of neoantigens and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) [8]. Interestingly, this patient exhibited an increased number of peripheral blood cells, such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which inhibit immunologic function. In our previous report, patients with stage II breast cancer had high blood levels of MDSC cells [9]. We speculated that CD8+ T cells may compete with MDSCs in the TME.

Increase in the number of both CD8+ T cells and TILs is associated with survival. Moreover, the high PD-L1 expression in patients with relatively high CD8+ T cell count indicates an adaptive immune mechanism. In the present case, the diffuse positive immunohistochemistry staining for CD8 and PD-L1 in breast cancer tissue was consistent with neoantigen production due to high mutation burden. In addition, in a murine model of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis, increased PD-L1 expression was observed in Tsc2-null lesions [10].

TNBC and immunotherapy

In a previous report on TNBC [11], T cells were shown to decrease in density as they moved in from the boundary of tumor cell clusters; this density increased as the T cells approached the center. Although tumor mutational burden was evaluated in that study, it was not prognostic and did not correlate with PD-L1 or CD8 gene expression. In patients with TNBC, PD-L1 is expressed mainly on tumor-infiltrating immune cells, rather than on the tumor cells, and can inhibit the anticancer immune response. Therefore, inhibition of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and PD-L1 may be a useful treatment strategy. Unresectable locally advanced or metastatic TNBC is an aggressive disease with poor outcomes. Nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab)-paclitaxel may enhance the anticancer activity of atezolizumab. Based on the results of available trials [12, 13], this combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy clearly benefited patients with PD-L1-positive tumors and may be considered for recurrent cases. On the other hand, first-line pembrolizumab monotherapy was shown to have a manageable safety profile and durable antitumor activity therapy for patients with PD-L1-positive metastatic TNBC [14]. Merck announced the phase 3 KEYNOTE-119 trial on Keytruda® (pembrolizumab) as monotherapy for the second-line or third-line treatment of patients with metastatic TNBC [15]. However, that trial did not meet its pre-specified primary endpoint of superior overall survival (OS), compared with that of chemotherapy with capecitabine, eribulin, gemcitabine, or vinorelbine. As per the study protocol, the other endpoints were not formally tested because the primary endpoint of OS was not met.

At present, research to identify biomarkers of good response to immunotherapy is still ongoing. Some of the possible biomarkers that are being explored include TILs, tumor PD-L1 expression, and tumor mutational burden. However, all the mechanisms involved in immunotherapy have not been completely understood, thereby making it difficult to identify a biomarker that can broadly work for all the approved immunotherapies. For patients with PD-L1-positive tumors (that is, ≥ 1% PD-L1 expression on tumor-infiltrating immune cells), first-line treatment with nab-paclitaxel and atezolizumab was recommended, when available [16]. Further characterization of the immune microenvironment may highlight the targets for immune-based therapy of TNBC.

To develop an immunohistochemical scoring algorithm that includes PD-L1 expression for both tumor and immune cells (that is, combined positive score) [17], the varying clinicopathologic features and survival outcomes of TNBC need to be determined according to the different histologic subtypes. Medullary carcinoma and apocrine adenocarcinoma have excellent prognosis, whereas mixed lobular–ductal carcinoma and metaplastic carcinoma are the most aggressive subtypes [18]. TNBC can be categorized into six different molecular subtypes that are characterized by distinct biological features. The different molecular clusters described were basal-like 1, basal-like 2, immunomodulatory, mesenchymal, mesenchymal stem-like, and luminal androgen receptor. These TNBC molecular subtypes can be targeted by specific therapies [19] and have substantial genomic heterogeneity with distinct patterns of genomic alterations and putative underlying driver mutations [20].

In fact, identification of biomarkers that can guide treatment decisions in TNBC remains a clinically unmet need. Understanding the mechanisms that drive resistance is the key to the development of novel therapeutic strategies that can help prevent metastatic disease and, ultimately, improve survival in this patient population [21].

TSC2 and breast cancer

Mutation in the TSC2 gene alters the function of the TSC1/TSC2 complex, so that it no longer functions as a guanosine-5'-triphosphate (GTP) ase-activating protein. As a result, the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity is promoted, which increases protein synthesis. This increased protein synthesis in TSC was thought to be associated with the clinical manifestations, such as dysplasia, and tumorigenesis due to abnormal cell proliferation and neovascularization.

At a glance, breast cancer appears to be unrelated to PKD. The endonuclease III-like 1 (NTHL1) gene may be involved in DNA repair and is present in the 68-bp region, downstream of the TSC2 gene. The TSC2 gene is located upstream of the NTHL1 gene by 5′-to-5′ (head-to-head) placement, and the promoters of both NTHL1 and TSC2 genes overlap. The NTHL1 gene was said to be causative of multiple cancers, including breast cancer [22]. Furthermore, the gene is located in a 3′-to-3′ (tail-to-tail) orientation with the solute carrier family 9 isoform A3 regulatory factor 2 (SLC9A3R2) gene [23]. The SLC9A3R2 gene of the Na+/H+ exchange carrier controlling element is present in the 8778-bp region upstream of the TSC2 gene. These genes were thought to be located on chromosome 16p13.3, from the centromere side, in the order of TSC2, NTHL1, and SLC9A3R2 [24]. The SLC9A3R2 gene is broadly expressed in fat tissue and is a housekeeping gene that consistently showed low variance as the normalizing genes in the microarray profiles of all breast cancer datasets [25].

Polycystic kidney disease type 1 (PKD1) and Rubinstein–Taybi (RTS) syndrome

One of our patient’s younger brothers had ADPKD and died at a young age, whereas the other younger brother had intellectual impairment, which was most likely RTS [26]. RTS comprises multiple congenital anomalies and is characterized by intellectual disability, postnatal growth deficiency, microcephaly, broad thumbs and halluces, and dysmorphic facial features. It is caused by heterozygous mutation in the gene that encodes the transcriptional coactivator cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-response element-binding protein (CREB) binding protein (CREBBP) on chromosome 16p13.3 [27]. Inhibition of hypothalamic CREBBP results in profound obesity, impaired glucose homeostasis, and increased food intake [28]. Surprisingly, one of our patient’s younger brothers has DM, is stout, and may have CREBBP gene deficiency. The unique feed–forward signaling loop of cAMP−CREB−glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β)−cAMP is potentially self-sustaining, and blocking it at any point would break this vicious cycle and significantly reduce PKD progression [29]. Therefore, the younger brother was unlikely to have PKD.

Conclusions

In this patient with TNBC complicated with ADPKD, there were high mutation burden, increased CD8 and PD-L1 expressions in the breast cancer tissue, and neoantigen production. If recurrence occurs, PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors may be effective.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- ADPKD:

-

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

- cAMP:

-

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CD8:

-

Cluster of differentiation 8

- CGS:

-

Contiguous gene syndrome

- CREB:

-

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate-response element-binding protein

- CREBBP:

-

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate-response element-binding protein binding protein

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- MDSC:

-

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- nab:

-

Nanoparticle albumin-bound

- NTHL1 :

-

Endonuclease III-like 1

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death 1

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed cell death ligand 1

- PKD:

-

Polycystic kidney disease

- PKD1 :

-

Polycystic kidney disease 1

- PKD2 :

-

Polycystic kidney disease 2

- RTS:

-

Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome

- SLC9A3R2 :

-

Solute carrier family 9 isoform A3 regulatory factor 2

- TIL:

-

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte

- TME:

-

Tumor microenvironment

- TNBC:

-

Triple-negative breast cancer

- TSC:

-

Tuberous sclerosis complex

- TSC2 :

-

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex 2

- Tsc2:

-

Tuberous sclerosis complex 2

References

Laass MW, Spiegel M, Jauch A, Hahn G, Rupprecht E, Vogelberg C, et al. Tuberous sclerosis and polycystic kidney disease in a 3-month-old infant. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19(6):602–8.

Furlano M, Barreiro Y, Marti T, Facundo C, Ruiz-Garcia C, DaSilva I, et al. Renal angiomyolipoma bleeding in a patient with TSC2/PKD1 contiguous gene syndrome after 17 years of renal replacement therapy. Nefrologia. 2017;37(1):87–92.

Harris PC. The TSC2/PKD1 contiguous gene syndrome. Contrib Nephrol. 1997;122:76–82.

Wang B, Tu YF, Tsai YS. Teaching NeuroImages: Huge carotid artery aneurysm in TSC2/PKD1 contiguous gene syndrome. Neurology. 2017;89(8):e93–4.

Longa L, Brusco A, Carbonara C, Polidoro S, Scolari F, Valzorio B, et al. A tuberous sclerosis patient with a large TSC2 and PKD1 gene deletion shows extrarenal signs of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Contrib Nephrol. 1997;122:91–5.

Higashihara E, Horie S, Kinoshita M, Harris PC, Okegawa T, Tanbo M, et al. A potentially crucial role of the PKD1 C-terminal tail in renal prognosis. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018;22(2):395–404.

Kleczko EK, Marsh KH, Tyler LC, Furgeson SB, Bullock BL, Altmann CJ, et al. CD8(+) T cells modulate autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease progression. Kidney Int. 2018;94(6):1127–40.

Mittica G, Ghisoni E, Giannone G, Aglietta M, Genta S, Valabrega G. Checkpoint inhibitors in endometrial cancer: preclinical rationale and clinical activity. Oncotarget. 2017;8(52):90532–44.

Gonda K, Shibata M, Ohtake T, Matsumoto Y, Tachibana K, Abe N, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells are increased and correlated with type 2 immune responses, malnutrition, inflammation, and poor prognosis in patients with breast cancer. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(2):1766–74.

Maisel K, Merrilees MJ, Atochina-Vasserman EN, Lian L, Obraztsova K, Rue R, et al. Immune Checkpoint Ligand PD-L1 Is Upregulated in Pulmonary Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018;59(6):723–32.

Li X, Gruosso T, Zuo D, Omeroglu A, Meterissian S, Guiot MC, et al. Infiltration of CD8(+) T cells into tumor cell clusters in triple-negative breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(9):3678–87.

Schmid P, Adams S, Rugo HS, Schneeweiss A, Barrios CH, Iwata H, et al. IMpassion130 Trial Investigators. Atezolizumab and Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2108–21.

Schmid P, Chui SY, Emens LA. Atezolizumab and Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(10):987–8.

Adams S, Loi S, Toppmeyer D, Cescon DW, De Laurentiis M, Nanda R, et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-positive, metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: cohort B of the phase II KEYNOTE-086 study. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(3):405–11.

Merck’s Keytruda Fails to Meet Endpoint in Phase 3 KEYNOTE-119 Breast Cancer Trial. May 24, 2019. https://www.trialsitenews.com/12762-2/

No authors listed. Atezolizumab Combo Approved for PD-L1-positive TNBC. Cancer Discov. 2019 May;9(5):OF2.

Kulangara K, Zhang N, Corigliano E, Guerrero L, Waldroup S, Jaiswal D, et al. Clinical Utility of the Combined Positive Score for Programmed Death Ligand-1 Expression and the Approval of Pembrolizumab for Treatment of Gastric Cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143(3):330–7.

Liao HY, Zhang WW, Sun JY, Li FY, He ZY, Wu SG. The Clinicopathological Features and Survival Outcomes of Different Histological Subtypes in Triple-negative Breast Cancer. J Cancer. 2018;9(2):296–303.

Jézéquel P, Kerdraon O, Hondermarck H, Guérin-Charbonnel C, Lasla H, Gouraud W, et al. Identification of three subtypes of triple-negative breast cancer with potential therapeutic implications. Breast Cancer Res. 2019;21(1):65.

Wilson TR, Udyavar AR, Chang CW, Spoerke JM, Aimi J, Savage HM, et al. Genomic Alterations Associated with Recurrence and TNBC Subtype in High-Risk Early Breast Cancers. Mol Cancer Res. 2019;17(1):97–108.

Garrido-Castro AC, Lin NU, Polyak K. Insights into Molecular Classifications of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Improving Patient Selection for Treatment. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(2):176–98.

Rivera B, Castellsague E, Bah I, van Kempen LC, Foulkes WD. Biallelic NTHL1 Mutations in a Woman with Multiple Primary Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(20):1985–6.

Dauwerse JG, Bouman K, van Essen AJ, van Der Hout AH, Kolsters G, Breuning MH, et al. Acrofacial dysostosis in a patient with the TSC2-PKD1 contiguous gene syndrome. J Med Genet. 2002;39(2):136–41.

Imai K, Sarker AH, Akiyama K, Ikeda S, Yao M, Tsutsui K, et al. Genomic structure and sequence of a human homologue (NTHL1/NTH1) of Escherichia coli endonuclease III with those of the adjacent parts of TSC2 and SLC9A3R2 genes. Gene. 1998;222(2):287–95.

Szasz AM, Li Q, Eklund AC, Sztupinszki Z, Rowan A, Tokes AM, et al. The CIN4 chromosomal instability qPCR classifier defines tumor aneuploidy and stratifies outcome in grade 2 breast cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56707.

Rubinstein JH, Taybi H. Broad thumbs and toes and facial abnormalities. A possible mental retardation syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1963;105:588–608.

Hennekam RC, Tilanus M, Hamel BC, Voshart-van Heeren H, Mariman EC, van Beersum SE, et al. Deletion at chromosome 16p13.3 as a cause of Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome: clinical aspects. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52(2):255–2.

Moreno CL, Yang L, Dacks PA, Isoda F, Deursen JM, Mobbs CV. Role of Hypothalamic Creb-Binding Protein in Obesity and Molecular Reprogramming of Metabolic Substrates. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166381.

Kakade VR, Tao S, Rajagopal M, Zhou X, Li X, Yu AS, et al. A cAMP and CREB-mediated feed-forward mechanism regulates GSK3beta in polycystic kidney disease. J Mol Cell Biol. 2016;8(6):464–76.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient and her family members for their participation in this study. We want to dedicate this article to the families lost in the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. We are also grateful to the study coordinators (Masahiro Toyama, Masahiko Iida) for assistance with study subject recruitment. We acknowledge Katsuji Saito (Fukushima Medical University) for institutional support.

Funding

There are no sources of funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KG contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and drafting, and critical revision of the manuscript. TA, TN, Eiko H, NK, and YR were involved in data acquisition and manuscript design. YM and SH contributed to data analysis, and drafting, and critical revision of the manuscript. KT, NA, TO, KS, KK, SS, and ST contributed to study conception and design, and data analysis and interpretation. Eiji H contributed to critical revision of the manuscript. TA, TN, Eiko H, NK, YR, YM, SH, KT, NA, TO, Eiji H, KS, KK, SS, and ST agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved, and made substantial contributions to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

According to local ethical guidelines, all blood samples were obtained for storage and analysis only after written informed consent had been obtained from the patient and her family members. Written informed consent was obtained using a form approved by the local ethics committee: the Ethical Review Board of Japan Community Healthcare Organization Nihonmatsu Hospital (no. 00033). All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation at Fukushima Medical University and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2000.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and family members for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gonda, K., Akama, T., Nakamura, T. et al. Cluster of differentiation 8 and programmed cell death ligand 1 expression in triple-negative breast cancer combined with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and tuberous sclerosis complex: a case report. J Med Case Reports 13, 381 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2274-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2274-6